Abstract

Background

Recent research indicates that currently active or recently detoxified substance abusers make more disadvantageous decisions on a simulated gambling task (SGT). This study expands upon the current literature by using the SGT to examine decision making in long-term abstinent alcoholics (mean of 6.6 years abstinence) who do not have antisocial personality disorder or a history of conduct disorder.

Methods

102 subjects (58 controls, 44 abstinent alcoholics) were tested on the SGT where subjects choose cards from 4 different decks that vary in terms of the magnitude of the immediate win (large/small) and the magnitude of long-term loss (large/small). The association of SGT performance with alcohol use variables, with the number of externalizing symptoms, and with personality measures of social deviance were examined.

Results

Compared to controls, long-term abstinent alcohol dependent subjects had more externalizing symptoms, had personality profiles associated with a proneness to social deviance, and made more disadvantageous decisions on the SGT. The magnitude of disadvantageous decision making was associated with the duration of peak alcohol use, but was only associated with one (low socialization) measures of socially deviant personality traits.

Conclusions

The results suggest that alcoholics can achieve long-term abstinence in spite of persistent deficits in decision making and abnormal personality profiles. The decision making deficits may either be the result of long-term alcoholism or may reflect a factor predisposing to alcoholism that persists with abstinence. The possibility is raised that alcoholics who cannot achieve long-term abstinence are even more impaired on their decision making and have more abnormal personality profiles than the abstinent alcoholics studied here.

Keywords: Simulated Gambling Task, Alcohol Abuse, Long-Term Abstinence, Risk Taking, Decision-Making

Introduction

Alcoholism and drug abuse are disorders in which people continue their use of harmful substances despite major long-term negative consequences (e.g. in the areas of employment, family, education, and health). A number of studies (Bechara, 2001; Bechara et al., 2001; Grant et al., 2000) have examined the mechanisms underlying this aspect of substance dependence using the simulated gambling task (SGT) developed by Bechara and colleagues (Bechara et al., 1994). The SGT simulates real-life decision-making that requires an individual to weigh reward and punishment in an atmosphere of uncertain outcomes. Subjects are asked to choose between decks of cards that have small positive gains associated with relatively smaller negative consequences (the good decks) and decks of cards with large positive gains with even larger negative consequences (the bad decks). If a subject chooses from the good decks, over the long run they will gain money, and if they choose from the bad decks, they will lose money. These choices are not dissimilar from those made by substance abusers. They too continually weigh the short-term rewards against the long-term consequences of their behavior. A hallmark of drug and alcohol abuse is that users persist in behaviors that have short-term benefits (e.g., intoxication) despite long term major negative consequences.

The gambling task was initially developed to study patients with acquired sociopathy due to damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997). Such patients often take part in risky behaviors that are immediately gratifying while ignoring negative future outcomes. It is thought that they cannot see beyond short-term rewards to potential long-term consequences (Bechara et al., 1994). Compared with controls, when playing the SGT, patients with ventromedial prefrontal lesions consistently choose to draw more cards from decks with larger immediate rewards and long term net losses, than from decks with a smaller immediate reward, smaller delayed punishments and long-term net gains (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997). Although they performed poorly on the SGT, these ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients performed normally in other cognitive domains (Bechara et al., 1998). Ventromedial prefrontal dysfunction may predispose an individual to make disadvantageous personal choices possibly leading to socially inappropriate, or socially deviant behavior (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997), or to drink excessively even when it leads to significant problems.

Studies show that currently active or recently detoxified alcoholics (Bechara, 2001; Bechara and Damasio, 2002; Mazas et al., 2000) and drug abusers (Grant, 2000; Petry et al., 1998) exhibit performance similar to that of ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients on the SGT. Their performance is characterized by favoring larger immediate rewards while disregarding long-term negative consequences. This pattern of impaired decision making resembles the typical decisions made by an alcoholic to drink excessively to experience the immediate pleasure of intoxication in spite of the many longer-term consequences of intoxication (Clark and Robbins, 2002). Those studies that have compared alcoholics with vs. without antisocial psychopathology indicate that disadvantageous decision making is more strongly associated with antisocial personality (ASP) and conduct disorder (CD) than with alcoholism (Mazas, 2002; Mazas et al., 2000; Petry, 2002). In a review paper, Finn (Finn et al., 2002) suggests that disadvantageous decision making reflects a stable disposition to behavioral undercontrol/social deviance, which is also a major risk factors for alcoholism (Finn et al., 2000; Sher et al., 1991).

It is not clear whether impaired decision making that over emphasizes immediate rewards while discounting or even disregarding long-term negative consequences is a symptom of active alcoholism, which might resolve with long-term abstinence, a consequence of chronic alcohol abuse on brain structure and function which may or may not resolve with long-term abstinence, or a stable characteristic of an underlying disinhibitory disposition in alcoholics that would predate active alcohol abuse and persist into long-term abstinence. Moreover, looking at alcoholism from the perspective that abusive drinking is a symptom of the underlying alcoholic disorder, it is a tenable hypothesis that gambling task impairment supports abusive drinking and lessens the likelihood of achieving long-term abstinence. If such were the case, one would expect that alcoholics who are able to achieve long-term abstinence would also evidence relatively normal performance on the SGT (i.e., those with SGT impairments would not have achieved long-term abstinence). There have been no studies to date of SGT performance in long-term abstinent alcoholics.

The current study was designed to examine disadvantageous decision-making in long-term abstinent alcoholics. It examined SGT performance in a sample of alcoholics who have been abstinent for an average of 6.6 years and for a minimum of at least six months. Rather than include alcoholics with diagnosable ASP or past CD, we decided to exclude individuals with such diagnoses, and to assess the association of disadvantageous decision making with the number of symptoms of ASP and CD and with personality measures of social deviance proneness. Social deviance proneness, assessed with the Socialization Scale of the California Personality Inventory (Gough, 1969) and the MMPI Psychopathic Deviance Scale (Hathaway, 1989), is thought to reflect the basic personality dispositions that lead to antisocial psychopathology (Finn et al., 2000; Gough, 1969; Hathaway, 1989). The current study tests the hypothesis that long-term abstinent alcoholics will demonstrate disadvantageous decision making on Bechara’s SGT. It also tests the hypothesis that disadvantageous decision making is associated with behaviors and personality traits that reflect a proneness to social deviance.

Methods

Participants

A total of 102 participants were recruited from the community at large by canvassing AA meetings, café postings, newspaper advertisements and a local Internet site. Two groups were recruited, controls (n=58, 21 men and 37 women), and abstinent alcoholics (n=44, 26 men and 18 women). The inclusion criteria for the control group was a lifetime drinking average of less than 30 drinks per month with no periods of more than 60 drinks per month. Abstinent alcoholic’s needed to meet the lifetime criteria for alcohol dependence, have a lifetime drinking average of at least 100 drinks per month for men (80 drinks per month for women), and be abstinent for at least six months.

Exclusion criteria for both groups were 1) history or presence of an Axis I diagnosis on the Diagnostic Interview Scale (DIS: (Robins, 1998)) (including ASP and CD), 2) history of drug dependence other than nicotine or caffeine, 3) significant history of head trauma or cranial surgery, 4) history of diabetes, stroke, or hypertension that required medical intervention, or of other significant neurological disease, 5) clinical evidence of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, and 6) current substance abuse other than caffeine or nicotine. The number of potential abstinent alcoholic subjects rejected for various reasons is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exclusion of Abstinent Alcoholics(ages 35–55)

| Reason for Exclusion | Number Excluded |

|---|---|

| Current Drug Abuse or Lifetime Drug Dependence | 25 |

| Failed Alcohol Dependence, Use, or Abstinence Criteria | 47 |

| Met Medical Exclusion Criteria | 28 |

| Met Psychiatric Exclusion Criteria | 29 |

| TOTAL | 121 |

All participants were informed of the study’s procedures and aims, and signed a consent form prior to their participation. Subjects participated in four sessions that lasted between an hour and a half and three hours, which included clinical, neuropsychological, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging assessments. Control subjects were asked to abstain from using alcohol for at least 24 hours prior to any lab visits, and a Breathalyzer test was administered to all subjects prior to each session. We had one positive Breathalyzer test result, on one ‘abstinent alcoholic’ subject assessed prior to an EEG session; that subject was excluded from the study. Subjects who completed testing were paid for their time and travel expenses, and those who completed the entire study were also given a completion bonus.

Assessment

All subjects were assessed for psychiatric diagnoses using the DIS (Robins, 1998). Subjects were interviewed on their drug and alcohol use using the lifetime drinking history (LDH) methodology (Skinner and Sheu, 1982; Sobell and Sobell, 1990; Sobell et al., 1988), medical histories were reviewed, and liver functions tested. Personality traits reflecting social deviance were assessed using the Psychopathic Deviance (Pd) Scale of the MMPI-2 (Hathaway, 1989) and the Socialization Scale (So) of the California Psychological Inventory (Gough, 1969). The extent of externalizing symptoms was indicated by the sum of positive Antisocial Personality Disorder and Conduct Disorder items from the DIS.

Gambling Task Administration

The game begins with $2000 of ‘fake’ money. The subjects’ task is to try and win as much money as possible. They are asked to select one card at a time from one of the four decks shown. Some cards will add money and some cards will subtract money from their running total. Subjects are told that they can switch from one deck to another at any time and as often as they wish. Each deck has a total of 60 cards with the game ending after a total of 100 cards are selected. They are told that they will not know when the game will end, that they should continue to choose from whichever decks they like until the game ends, that some decks are better than others, that the computer does not change the order of cards after the game starts, make you lose at random, or make you lose money based on the last card chosen. The dependent variable reflects advantageous decision making and is indexed by the number of cards chosen from the good decks minus the number of cards chosen from the bad decks.

Alcohol Use Variables

Based upon subject’s responses on the LDH, alcohol use variables were defined. Alcohol lifetime duration refers to the number of months of alcohol consumption in the individual’s lifetime, while peak duration refers to the number of months of peak alcohol use. Alcohol lifetime dose is the average number of drinks per month of alcohol consumption over the subject’s lifetime, while peak dose is the number of drinks per month during their period of peak alcohol consumption. Duration of abstinence was also included as an alcohol use variable.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, 1990). Analysis of variance for unbalanced designs was carried out using the General Linear Models procedure. The robustness of main effects to outliers was assessed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon test. Spearman correlations were examined because they are robust and resistant to outliers.

Results

Table 2 presents the demographic, alcohol use, externalizing symptom and deviance proneness measures for males and females in the abstinent alcoholic and control groups. There were no group or gender differences in subject age or years of education. Abstinent alcoholics and males had much larger numbers of externalizing symptoms on the DIS than did controls or females, with the group difference accounting for 31.3% of the variance of the measure, while the gender difference accounted for 5.3% of the variance. There was an enormous group difference in socialization scores (accounting for 44.2% of the CPI socialization score variance), with no gender difference present. Finally, there were much higher MMPI Psychopathic Deviance Scale scores in the abstinent alcoholics (with group accounting for 18% of the measures variance), with no gender differences.

Table 2.

Demographic, Alcohol Use, Externalizing Symptom, and Social Deviance Proneness Measures for the Abstinent Alcoholic and Control Samples

| Abstinent Alcoholics | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n=26) Mean ± St. Err. | Females (n=18) Mean ± St. Err | Males (n=21) Mean ± St. Err | Females (n=37) Mean ± St. Err | |

| Demographic Variables | ||||

| Age in years | 45 ± 1.34 | 47.4 ± 1.34 | 43.1 ± 1.36 | 44.8 ± 1.11 |

| Years of Education | 15.5 ± .43 | 15.6 ± .5 | 16 ± .4 | 16.4 ± .28 |

| Alcohol Use Variables | ||||

| Duration of Alcohol Use (mos) | 251 ± 17.4 | 246 ± 21.2 | 291 ± 31.4 | 306 ± 22.4 |

| Average Alcohol Dose (drks/mo) | 167 ± 26.3 | 134 ± 19.8 | 6.63 ± 1.75 | 6.07 ± .89 |

| Duration of Peak Alcohol Use (mos) | 52.3 ± 6.29 | 82.8 ± 19.2 | 106 ± 30 | 112 ± 19.1 |

| Peak Alcohol Dose (drks/mo) | 353 ± 51.5 | 311 ± 66.8 | 14.7 ± 3.12 | 16.8 ± 3.25 |

| Abstinence Duration (yrs) | 6.79 ± 1.19 | 7.13 ± 1.36 | N/A | N/A |

| Externalizing Sxa | 16 ± 1.52 | 11.74 ± 1.61 | 7.19 ± 1.37 | 3.51 ± .43 |

| Social deviance proneness measures | ||||

| CPI: Socialization Scale | 27 ± 1.13 | 28.9 ± 1.33 | 36.6 ± .94 | 37.5 ± .56 |

| MMPI-PD | 23.1 ± 1.36 | 25.3 ± 1.73 | 17.9 ± .72 | 19.1 ± .78 |

Sum of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Conduct Disorder Symptoms from the DIS

Gambling Task Performance

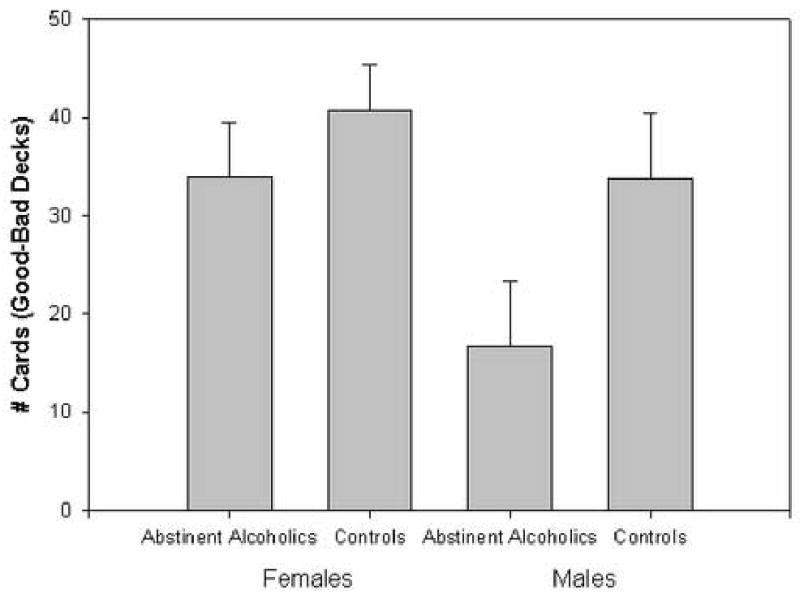

We examined gambling task performance as a function of group (abstinent alcoholic vs. control) and gender. Since the sampling design was not balanced, group and gender needed to be evaluated with the other effect partialled out to indicate the effect of each variable independent of the other. In this analysis there was a significant main effect of group (F(1,,98) = 4.03, p < .05), and a significant main effect of gender (F(1,,98) = 4.08, p < .05), with a nonsignificant group by gender interaction (F(1,98) = 0.36, p > 0.54). When the data were analyzed for main effects using the Wilcoxon test, the effects of group and gender remained significant, indicating that those effects were not due to a few extreme values.

Association of Gambling Task Performance with subject variables

Across the entire sample there were significant correlations of gambling task performance with socialization scores (r = .31, p < .002) and the number of externalizing symptoms (r = −.19, p = .05), but no association with the MMPI Pd scale (r = −.07, p > .50). None of these measures was associated with gambling task performance in either the abstinent alcoholic or control group when these groups were examined separately. The only within group correlation that even had a trend toward statistical significance was the correlation of SGT score with the socialization score in the control group (r = .19, p > .14); all other correlations had |r|’s < .11 (p’s > .40).

Association of Gambling Task Performance with alcohol use variables

Gambling task performance was negatively correlated in the abstinent alcoholic group with duration of alcohol use (r = −.30, p < .05) and duration of peak alcohol use (r = −.35, p < .03). After partialling out the contribution of age (older subjects have a longer life in which to use or use at a high dose), the duration of alcohol use remained a weak trend (r = −.23, p = .14) while duration of peak use remained significant (r = −.30, p < .05). There were no associations with duration of abstinence.

Discussion

The major result of the current investigation is the finding of gambling task impairment in alcoholics who had been abstinent for a minimum of six months and an average of 6.6 years. This result demonstrates that individuals with persistent decision making impairment on the SGT are able to achieve long-term abstinence.

It is important to note that the long-term abstinent alcoholics studied here had personality profiles with regard to externalizing symptoms and social deviance that were grossly different from controls. Compared to the controls, the abstinent alcoholics had dramatically lower socialization scores on the California Personality Inventory, had highly elevated psychopathic deviance scores on the MMPI and had more than twice the number of antisocial personality and conduct disorder symptoms on the DIS. Our data demonstrate that alcoholics who have twice the number of externalizing symptoms as controls and who have personality profiles that reflect a proneness to social deviance (short of actual ASP or CD) can achieve long-term abstinence. Advantageous decision making was associated with higher scores on the socialization scale, but was only modestly associated with low externalizing symptoms and not associated with psychopathic deviance. This suggests that poor decision making in the current sample did not reflect variations in social deviance or antisocial tendencies.

Only forty-five percent of the potential volunteer subjects for the abstinent alcoholic sample were excluded for drug or psychiatric comorbidity. In addition, none of our potential volunteer subjects with a minimum of six months of abstinence were excluded for a DIS lifetime diagnosis of antisocial personality (ASP) or conduct disorder (CD). We don’t know if these low comorbidiites in the volunteer sample are because individuals with such comorbidities are less likely to achieve long-term abstinence (and thus be potential volunteers for our study), or are simply less likely to volunteer for research studies in response to flyers at AA meeting places and advertisements in newspapers. In either case, the data suggests that our recruitment efforts selected for alcoholics with relatively low drug and psychiatric comorbidities (including zero comorbidity for ASP and CD). Our data also suggest that such lower comorbidities are characteristics of alcoholics who are able to achieve long-term abstinence; however, careful community based studies would be needed to establish whether such is the case. Finally, our study illustrates the difficult decisions in study design (e.g., whether or not to exclude individuals with comorbid drug and/or psychiatric condiditons) and the complexity of analysis and interpretation inherent in studying alcoholic vs. control samples. These arise from the confounding in clinical samples of the effects of factors predisposing to alcoholism, the effects of comorbid conditions, the effects associated with preclinical signs and symptoms of such comorbid conditions when individuals meeting actual diagnostic criteria for such conditions are excluded from study, and the effects of alcoholism per se.

Impairment on the SGT may result from impairments in the cognitive or motivational realm, or in both. One limitation of the current study is that in our implementation of the SGT we did not save individuals’ choices on successive cards (we saved only the total number of cards chosen from each deck. Therefore, we were unable to examine changes in performance with task progression, which would have provided hints as to whether individuals were able to learn the task contingencies over time. Such data would have helped differentiate between a motivational vs. cognitive disturbance underlying impaired SGT performance. We now routinely save such trial-by-trial data.

Nonetheless, our data indicate that individuals with impairments on the SGT can maintain long-term abstinence. Our results suggest that although these abstinent alcoholics remain susceptible to making poor decisions and have personality profiles associated with deviance proneness, they somehow managed to compensate for their deficits by recruiting other mechanisms of behavioral control that enable them to resist drinking. Our results raise the question of whether alcoholics who are unable to maintain long-term abstinence have even more abnormal psychological profiles and more impaired decision making on the SGT. Another potential implication of this research is that the achievement of long-term abstinence may involve different processes in different subgroups of acoholics – the results here provide some hints as to how those subgroups may be constituted. There may be different mechanisms of behavioral control used to maintain abstinence by alcoholics who evidence impairment on the SGT compared to alcoholics who exhibit normal performance on the SGT. These issues deserve further research and may illuminate important processes involved in the attainment of long-term abstinence.

We also found that, in our sample of abstinent alcoholics, the magnitude of the SGT impairment is unaffected by duration of abstinence and is positively associated with the duration of peak alcohol use. This suggests two alternatives. The first is that gambling task impairment in part reflects the consequence of chronic alcohol abuse on the brain, and that this effect does not resolve with abstinence, even very long-term abstinence. The other is that the findings reflect some pre-existing factor in alcoholics that accounts for both impaired decision making and the severity of alcoholism. The current data cannot differentiate between these two alternatives.

Finally, the results raise the possibility that the abstinent alcoholic subjects studied here have abnormalities in their ventromedial prefrontal cortex. We are in the process of examining structural imaging data from these subjects to test this hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Gambling task performance (number of cards chosen from the good decks minus number of cards chosen from the bad decks) for abstinent alcoholics and controls separately for males and females. Gambling task performance was worse for abstinent alcoholics vs. controls (p<.05) and males vs. females (p<.05). No sex by group interaction was observed.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants AA11311 (GF) and AA13659 (GF), both from the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse. We also express our appreciation to the NRI recruitment and assessment staff, and to each of our volunteer research participants.

References

- Bechara A. Neurobiology of decision-making: risk and reward. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;6(3):205–16. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2001.22927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Anderson SW. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition. 1994;50(1–3):7–15. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H. Decision-making and addiction (part I): impaired activation of somatic states in substance dependent individuals when pondering decisions with negative future consequences. Neuropsychology. 2002;40(10):1675–89. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Anderson SW. Dissociation Of working memory from decision making within the human prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;18(1):428–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00428.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Sci Dig. 1997;275(5304):1293–5. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Dolan S, Denburg N, Hindes A, Anderson SW, Nathan PE. Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychology. 2001;39(4):376–89. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Robbins T. Decision-making deficits in drug addiction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(9):361. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Mazas CA, Justus AN, Steinmetz J. Early-onset alcoholism with conduct disorder: go/no go learning deficits, working memory capacity, and personality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):186–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N. The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(1):122–33. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HGPD. Manual for the California Psychological Inventory (So Scale) Consulting Psychological Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. Estimates of US children exposed to alcohol abuse and dependence in the family. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):112–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, Contoreggi C, London ED. Drug abusers show impaired performance in a laboratory test of decision making. Neuropsychology. 2000;38(8):1180–7. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway JMS. MMPI-2: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. The University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mazas CA. Decision-making biases and early-onset alcoholism. Dissert Abst Int. 2002;63(1B):539. [Google Scholar]

- Mazas CA, Finn PR, Steinmetz JE. Decision-making biases, antisocial personality, and early-onset alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(7):1036–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;162(4):425–32. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Bickel WK, Arnett M. Shortened time horizons and insensitivity to future consequences in heroin addicts. Addiction. 1998;93(5):729–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Buckholz K, Compton W. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Washington University School of Medicine; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS procedures guide: version 6. 3. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):427–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices: The lifetime drinking history and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1982;43(11):1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-reports issues in alcohol abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behavioral Assessment. 1990;12:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Riley DM, Schuller R, Pavan DS, Cancilla A, Klajner F, Leo GI. The reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking and life events that occurred in the distant past. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1988;49(3):225–232. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]