Abstract

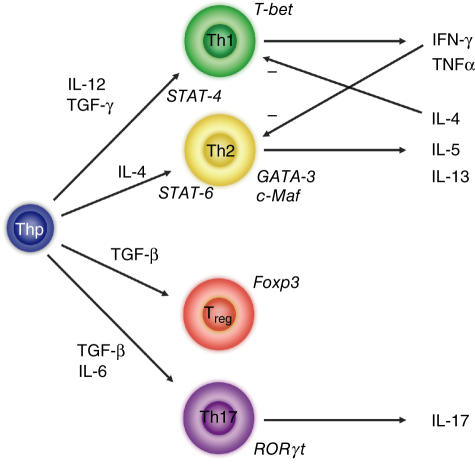

Uncommitted (naive) murine CD4+ T helper cells (Thp) can be induced to differentiate towards T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17 and regulatory (Treg) phenotypes according to the local cytokine milieu. This can be demonstrated most readily both in vitro and in vivo in murine CD4+ T cells. The presence of interleukin (IL)-12 [signalling through signal transduction and activator of transcription (STAT)-4] skews towards Th1, IL-4 (signalling through STAT-6) towards Th2, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β towards Treg and IL-6 and TGF-β towards Th17. The committed cells are characterized by expression of specific transcription factors, T-bet for Th1, GATA-3 for Th2, forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) for Tregs and RORγt for Th17 cells. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the skewing of murine Thp towards Th17 and Treg is mutually exclusive. Although human Thp can also be skewed towards Th1 and Th2 phenotypes there is as yet no direct evidence for the existence of discrete Th17 cells in humans nor of mutually antagonistic development of Th17 cells and Tregs. There is considerable evidence, however, both in humans and in mice for the importance of interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-17 in the development and progression of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (AD). Unexpectedly, some models of autoimmunity thought traditionally to be solely Th1-dependent have been demonstrated subsequently to have a non-redundant requirement for Th17 cells, notably experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and collagen-induced arthritis. In contrast, Tregs have anti-inflammatory properties and can cause quiescence of autoimmune diseases and prolongation of transplant function. As a result, it can be proposed that skewing of responses towards Th17 or Th1 and away from Treg may be responsible for the development and/or progression of AD or acute transplant rejection in humans. Blocking critical cytokines in vivo, notably IL-6, may result in a shift from a Th17 towards a regulatory phenotype and induce quiescence of AD or prevent transplant rejection. In this paper we review Th17/IL-17 and Treg biology and expand on this hypothesis.

Keywords: autoimmune disease, human, interleukin-17, lineage commitment, regulatory T cells, Th17, transcription factors

Introduction

Despite repertoire restriction in the thymus (‘central tolerance’) [1], the generation of a diverse T cell repertoire inevitably results in the production of T cell receptors with specificity for self-antigens [2,3]. Naive thymic emigrants therefore have the potential not only to respond to foreign antigens but also to components of self. Maturation of naive T cells depends critically on their interaction with the physicochemical environment and results in the development of cells with an effector (and memory) or regulatory function and the tolerization of autoreactive cells. It is critically important for the prevention of autoimmune diseases, therefore, that self-reactive naive T cells are not induced to mature into effector cells.

Murine experiments have demonstrated that naive CD4+ helper T cells (Thp) can develop into at least four types of committed helper T cells, namely T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17 and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (see below). In humans, there is evidence for the existence of all but discrete Th17 cells, although helper T cells secreting interleukin (IL)-17 have clearly been described [4]. IL-17 has a proinflammatory role and has been implicated in many inflammatory conditions in humans and mice, while Tregs have an anti-inflammatory role and maintain tolerance to self-components (see below).

Naive T cells can be induced to commit to particular lineages based on mode of stimulation, antigen concentration, costimulation and cytokine milieu [5]. The pathways of differentiation towards Th1 and Th2 cells have been elucidated previously with IL-4 signalling through signal transduction and activator of transcription-6 (STAT-6) possibly the most important cytokine in inducing Th2 cell differentiation [6] and IL-12 signalling through STAT-4, the central cytokine for commitment towards a Th1 lineage [7]. Once differentiated, each lineage is characterized by its own cytokine profile (with interferon (IFN)-γ being the signature cytokine of Th1 cells and IL-4 the archetypal cytokine of Th2 cells) and transcription factors (T-bet for Th1 [8,9], GATA-3 for Th2 [10], forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) for Tregs[11,12] and RORγt for Th17 cells [13]). Although Th1 responses have been implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases (AD) [14], reduction in IFN-γ signalling in mice (using IFN-γ knock-out strains or blocking IFN-γ) paradoxically worsens susceptibility to AD, most notably experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) and collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) [15,16] in the absence of exaggerated Th2 responses, implying the involvement of other effector populations. Recent evidence suggests that naive T cells (in mice) can also be induced to differentiate along a pathway favouring development of Th17 or Treg cells in a mutually exclusive manner [17–19]. Indeed, the Th17 population is important in mediating autoimmune diseases in animals [20,21].

As a result, a novel hypothesis has been proposed [22] with regards to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, namely that skewing of responses towards Th17 or Th1 and away from Treg (and Th2) may be responsible for the development and progression of AD or transplant rejection in humans and that blockade of critical cytokines may result in a shift in this polarization from Th17/Th1 phenotypes towards Treg and Th2 (i.e. that ‘regulation and ‘dysregulation’ are inducible and remediable). Our own observations suggest that human effector T cells can be identified that produce mutually exclusive IFN-γ or IL-17 profiles. Additionally, the hypothesis predicts that blockade of critical cytokines for generation of Th17 (namely IL-6) can result in remission of AD. The purpose of this review is to discuss the relevance of Th17 and Treg in human disease pathogenesis and progression.

IL-17

First cloned in 1993 from a murine cDNA library and known originally as CTLA-8 [23,24], IL-17A is a member of a family of IL-17 cytokines (IL-17A–F [25–29]) which are structurally homologous to each other and to a gene in the herpesvirus saimiri [23,30]. It was described initially as a product of activated and memory CD4+ T cells [23,30,30,31] but it is now known that the production of IL-17A is more ubiquitous and has been demonstrated in γδ T cells [32], CD8+ memory T cells [31,33], eosinophils [34], neutrophils [31] and monocytes [35]. Nevertheless, the predominant source of IL-17A (henceforth referred to as IL-17) remains the CD4+ memory T cell population [4,33].

The broad cell and tissue distribution of receptors for IL-17 (of which five have been described, namely IL-17R (the dominant receptor for IL-17A), IL-17RB, IL-17RC, IL-17RD and IL-17RE) in both humans and mice [27,29,30,36–38] and the diversity of expression through alternate splicing (reviewed in Moseley et al. 2003 [39]) argues for a pleiotropic spectrum of biological activity that may extend beyond the purely immunological, with the potential to act on many different cell types. Indeed, experiments in animals suggest that, unlike other cytokines, very little redundancy exists in the IL-17 network as IL-17R-deficient mice are very susceptible to lethal bacterial infections [40] and have inhibited T cell responses [41].

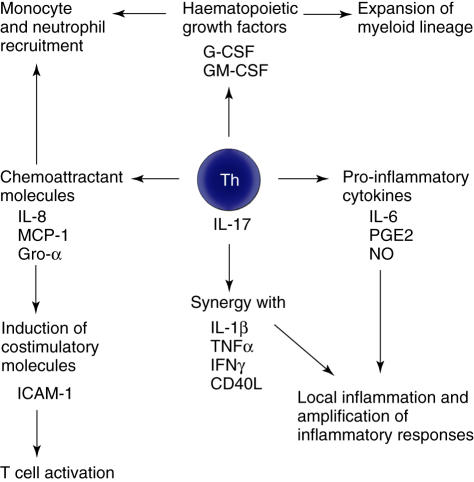

Nevertheless, the predominant function of IL-17 is thought to be as a proinflammatory mediator through a variety of mechanisms as summarized in Fig. 1. Locally, IL-17 stimulates production of IL-6, nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [4,30,42], while synergy with other inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IFN-γ[43–45] and CD40 ligand (by increasing surface levels of CD40) [46] leads to up-regulation of gene expression and progression and amplification of local inflammation. IL-17 mediates chemotaxis of neutrophils and monocytes to sites of inflammation through the chemoattractant mediators IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and growth-related protein (Gro)-α[45,47–49] while enhancing production of haematopoietic growth factors, such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage (GM)–CSF [26,50], which promote the growth and maturation of the recruited myeloid cells. Furthermore, IL-17 acts as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune response by augmenting the induction of co-stimulatory molecules such as ICAM-1 by other cytokines [45,51], thereby supporting T cell activation.

Fig. 1.

Proinflammatory effects of interleukin-17.

Although much is now known regarding the biology of IL-17 in murine systems and there is compelling evidence for an important role of IL-17 in inflammatory/autoimmune conditions [52,53], attempts to overexpress IL-17A ubiquitously in mice have failed due to generalized overproduction being lethal to developing embryos [54], while overexpression of IL-17E leads to a generalized inflammatory syndrome [55]. In humans, there is also a considerable body of evidence suggesting an important role for IL-17 in the aetiopathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, as discussed below.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Many lines of evidence support the role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of human RA [56]. Levels of IL-17 are elevated in the synovium of patients with RA [57,58] and synovial cultures from patients with RA spontaneously secrete IL-17 [59]; the source of this IL-17 is local production by T cells [59] and juxta-articular bone lymphocytes [60]. Pathologically, this cytokine can activate and enhance all mechanisms of tissue injury that have been described previously in rheumatoid arthritis. In particular, IL-17 can up-regulate and/or synergize with local inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 [61,62], IL-1β and TNF-α[61–63], pro-oxidants such as nitric oxide [64], as well as promoting extracellular matrix injury through stimulation of production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) [65,66] and inhibition of matrix repair components such as proteoglycans and collagens [67,68]. Furthermore, bone injury is enhanced [69] through promotion of osteoclastogenesis via osteoclast activating factor [57]. The combination of these factors has pathological effects on bone (resorption), extracellular matrix (degeneration), synovium (proliferation and inflammation), blood vessels (angiogenesis) and immune cells (recruitment and activation of monocytes and lymphocytes) in the rheumatoid joint. Not surprisingly, perhaps, intra-articular injection of IL-17 in normal mouse joints induces similar changes to RA [64] and excess local IL-17 (via adenovirus-mediated gene expression vectors) exacerbates significantly CIA [20].

Many of these effects of IL-17 on synovium and bone can be antagonized in vitro by treatment with IL-4, IL-13 or anti-IL-17 blocking antibody. These interventions can reduce IL-17-driven production of inflammatory factors such as leukaemia inhibitory factor [61], CCL20/MIP3α[70] as well as decreasing matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production and increasing tissue inhibitors of MMPs [67]. Some of the effects of IL-17 on articular cartilage can be attenuated by this approach in vivo[64], while blockade of IL-17 abrogates completely the spontaneous development of inflammatory arthritis in IL-1R antagonist-deficient mice [71], and mice lacking IL-17 are highly resistant to CIA [72].

Respiratory diseases

The importance of IL-17 to airways immunity is highlighted by the susceptibility of IL-17R knock-out mice to fatal pulmonary infections [40], which correlates with impaired neutrophil mobilization and bacterial clearance [48,73]. Similarly, the pulmonary response to local introduction of Escherichia coli endotoxin requires the presence of IL-17 for neutrophil accumulation in the bronchoalveolar space [47,73]. In mice and rats, there is evidence that activated lymphocytes from lung tissues can produce substantial amounts of IL-17 [47,74] and that the effect of IL-17 on the respiratory epithelium is to produce chemokines that favour a neutophilic infiltrate [47,75] and that increase neutrophil activity in vivo (as measured by myeloperoxidase and elastase release) [54,73].

Given these findings, it is perhaps not surprising that exaggerated IL-17 responses are implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory airways diseases. Human respiratory epithelial cells (and even some nonepithelial cells [34,75]), in a similar manner to murine ones, are responsive to IL-17 and can be stimulated to produce the same chemoattractant molecules [49,50,75–77], although there is now evidence supporting the notion that, under normal physiological conditions, the human bronchoalveolar space releases only very low amounts of IL-17 [78]. Severe respiratory inflammation precipitated by exposure to organic dust in humans is characterized by a marked increase in IL-17 levels in the broncheoalveolar lavage and a 50-fold increase in neutrophil recruitment to the lung [78]. Similarly, there are suggestions that in pulmonary asthma there is not only an increase in the number of IL-17-producing cells (T lymphocytes and eosinophils in broncheoalveolar lavage) in comparison to healthy controls both locally and within the circulation [34], but also higher levels of intracellular IL-17 in IL-17-producing cells than their healthy counterparts [34], although not all studies agree on this [79].

Pathologically, IL-17 is likely to exert its effects through exaggerated physiological mechanisms (highlighted above), namely synergy with other cytokines and the recruitment of neutrophils to lung tissues. Indeed, studies in allergen-sensitized mice suggest that neutrophil accumulation in the lungs following encounter with allergen is orchestrated by IL-17 transcription [80]. This latter mechanism may be critically important as neutrophilic infiltrates and neutrophil enzymatic activity correlate with the degree of bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with asthma [81]. IL-17-induced IL-6 release may have dual pathological significance, as IL-6 promotes neutrophil elastase release [82] (elastase activity is thought to be a key mediator in the pathogenesis of chronic airway diseases [83,84] and reciprocally controls activity of neutrophil IL-6 [85]) and is one of the mechanisms by which IL-17 stimulates release of mucin by respiratory epithelial cells [86]. Furthermore, IL-6 is important in the generation of IL-17-producing cells (mouse data, see below). Also, many of the effects of IL-17 on lung tissues can be antagonized by glucorticoids [34,75], which form the mainstay of treatment for inflammatory and allergic pulmonary diseases in humans.

Despite the evidence in favour of a significant role for IL-17 in inflammatory respiratory diseases in humans, most of the evidence is circumstantial and there is no direct evidence that this cytokine is the causative mediator or the central participant (i.e. that production of IL-17 is the trigger that precipitates these pulmonary diseases) and it may be that an elevated IL-17 response is simply part of the generalized inflammatory milieu. Certainly more evidence regarding the role of the cytokine in lung pathology is required.

Allograft rejection

Rejection of transplanted tissues involves interplay between mechanisms that maintain tolerance to the graft and factors that promote rejection. While immunological factors are important for both, the process of rejection is very much an inflammatory one and, as a consequence, the production of many proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-15, locally from infiltrating lymphocytes and resident cells [e.g. proximal renal tubular epithelium (PTEC)], is increased during acute renal graft rejection [87–89]. Studies in acute rat rejection models have also identified an elevation in IL-17 mRNA (in the renal allograft) and IL-17 protein (in infiltrating mononuclear cells) as early as day 2 post-transplant [90]. Similarly, IL-17 protein is elevated in human renal allografts during borderline (subclinical) rejection together with detectable IL-17 mRNA in the urinary MNC sediment of these patients; in control (non-rejecting) patients, IL-17 is not detectable in either the biopsy sample nor the urinary sediment [90]. These findings have also been described previously [91].

IL-17 induces IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and complement component C3 but not regulated upon activated normal T cell exposed expressed and secreted (RANTES) nor other complement components [91] by PTECs [90–92] via the src/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [92]. An additional mechanism, through synergy with CD40-ligand and proceeding via nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation, has also been described [46].

In human lung organ transplantation, IL-17 has also been reported as being elevated during acute rejection [93], while rat models have demonstrated that collagen type V-specific lymphocytes can mediate lung allograft rejection and express IL-17 locally at the site of rejection [94]. In cardiac allograft models, antagonism of the IL-17 network (via expression of an IL-17R-immunoglobin fusion protein) can reduce intragraft production of inflammatory cytokines (namely IFN-γ) and prolong graft survival [95]. This approach, however, is more successful at preventing acute, rather than chronic, vascular rejection [96] and may indicate a more important role for IL-17 in mediating early rather than late cardiac rejection. There may, in addition, be a role for IL-17 in inducing the maturation of alloreactive dendritic cells [97].

Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and other conditions

IL-17 has been implicated in a variety of other chronic human diseases, largely through demonstrations that the cytokine is overexpressed in these conditions. Examples include SLE [98], psoriasis [99,100], multiple sclerosis [101], systemic sclerosis [102] and chronic inflammatory bowel disease [103]. As this evidence is largely circumstantial, the exact role of IL-17 in these conditions is unclear.

With regard to infectious agents, it is possible that IL-17 has a role to play as a virulence factor, particularly given its homology to the gene in herpesvirus saimiri [23,30], a virus that is tropic for T cells [104]. While expression of murine IL-17 gene in a vaccinia virus does increase significantly its virulence [105], IL-17 knock-out strains of herpesvirus saimiri have unaltered pathogenicity [106], therefore the role of IL-17 in viral infections is unclear. Nevertheless, certain bacterial infections, notably Helicobacter pylori[107], Bacteroides fragilis[108] and periodontitis [109] are associated with particularly high levels of IL-17.

Similarly, there are suggestions that IL-17 may be involved in tumorigenesis, as IL-17 can both promote (e.g. human cervical cancer cell lines transplanted into nude mice) [110,111] and inhibit growth (e.g. haematopoietic tumours in immunocompetent mice) [112,113] of tumours in experimental animals. Although the role of IL-17 in tumour biology is unclear and evidence remains conflicting, IL-17 can be detected in some (such as ovarian, skin and prostatic cancers) [114–116] but not all (e.g. acute myeloid leukaemia) [117] human tumours and one emerging theme is that, when present, it promotes angiogenesis [111,114], for example through the up-regulation of angiogenic factors such as CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL6 and CXCL8 [118], thereby facilitating tumour growth and invasion. The alternative explanation is the possibility that vascular tumours may be better able to recruit activated/memory T cells, some of which will be IL-17 producers and, by virtue of being highly vascular, may portend a poorer prognosis.

In either event, there is now considerable evidence that IL-17 is involved in the aetiopathogenesis of many human disorders. Whether IL-17 is a key causative factor or is involved in the amplification of inflammatory responses has yet to be elucidated.

Regulatory T cells

A number of cell types with immunoregulatory capacity have been described in the literature. These include IL-10-secreting Tr1 cells [119], transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-secreting Th3 cells [120], Qa-1 restricted CD8+ cells [121], CD8+ CD28– T cells [122], CD8+ CD122+ T cells [123], γδ T cell receptor (TCR) T cells [124], natural killer (NK) cells [125,126], dendritic cells [127], apoptotic neutrophils [128], CD8+ CD28– cells [129–132], CD3+ CD4– CD8– cells [133,134] and naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ T cells [135]. Given that both human and murine knock-outs for CD4+ CD25+ cells develop severe autoimmune diseases [135–138], the focus of attention in the literature has been mainly on these regulatory T cells (referred to as Tregs in this paper).

In vitro, Tregs have the ability to inhibit proliferation and production of cytokines by responder (CD4+ CD25– and CD8+) T cells [139–141] to polyclonal stimuli, as well as to down-modulate the responses of CD8+ T cells, NK cells and CD4+ cells to specific antigens [139,142]. These predicates translate in vivo to a greater number of functions other than the maintenance of tolerance to self-components (i.e. prevention of autoimmune disease) [143] and include control of allergic diseases [144] and regulation of responses to microbial pathogens [145,146], as well as the ability to prevent transplant rejection [147] and to maintain gastrointestinal tolerance [148] and maternal tolerance to semiallogeneic fetal antigens [149]. Indeed, donor-specific Tregs can prevent allograft rejection in some models of murine transplant tolerance [150–152] through a predominant effect on the indirect alloresponse [153].

Although mutations in Foxp3, a forkhead-winged-helix transcription factor, are responsible for the loss of Treg function in both mice [137] and humans [154] and overexpression of Foxp3 in mouse cells leads to development of a Treg phenotype [154–156] and can act as a phenotypic marker [12,157], FoxP3 expression may not be an ideal marker for Tregs in humans [158] as FoxP3 is induced during TCR stimulation [159] (in much the same manner as CD25), and there is some debate as to whether the induced CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ population is suppressive or anergic [159,160]. Recent evidence has also implicated the IL-7 receptor (CD127) as a possible biomarker of Tregs in humans as the combination of CD4 and CD25 together with low expression of CD127 identifies a group of peripheral blood T cells, which are highly suppressive in functional assays and the highest expressors of FoxP3 [161].

Regulatory T cells function in an antigen-presenting cell (APC)-independent (at least in vitro) [162] and antigen-non-specific manner [141,163]. However, they do respond to their cognate antigen [164–166] and, while anergic in vitro[139], Tregs can proliferate extensively in response to antigen in vivo[167,168]. Although the exact mechanism by which Tregs exert their effect is unknown, it is believed that their suppressive function is contact-dependent on the basis of transwell experiments, where suppression could be abrogated via separation of Tregs and effector T cells by a semipermeable membrane [141,163,169], and demonstrations that signalling through the T cell receptor is critical to their function [170,171]. These observations are divergent with in vivo data showing an important role for TGF-β and IL-10 production as mediators of Treg activity [172,173], and do not exclude the possibility that Treg function may involve soluble mediators acting at very short distances from the cell or bound to the cell surface [174,175]. Despite suggestions that Tregs influence cells by direct contact, these cell-to-cell interactions are poorly mapped. Indeed, there is evidence that some of the activity of Tregs progresses through intermediaries, such as NK T [176] and mast cells [177], and that their effect on target T effector cells includes an arrest in cell cycle progression caused by uncoupling of IL-2 signalling [178,179]. Recently, a role for IFN-γ in the regulatory function of Tregs has also been proposed based on the up-regulation of IFN-γ mRNA in alloantigen-reactive Tregs in vivo hours after encounter with antigen and failure of skin graft tolerance in the presence of IFN-γ neutralization [180].

Tregs express constitutively CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4) and there are suggestions that signalling through this pathway may be important, for their function as antibodies (or Fab) to CTLA-4 can inhibit Treg-mediated suppression [181–183]. However, CTLA-4 is also inducibly expressed on CD4+ CD25– cells [184] and therefore these observations may be the result of CTLA-4 antibodies acting on effector rather than regulatory cells and could explain why the initial reports have been so difficult to reproduce in mice [141] and humans [140,140,185]. For a review on CTLA-4 in Treg biology, please see Sansom et al. [186].

Development and persistence of Tregs and IL-17-producing cells

Tregs

It is now clear that CD4+ CD25+ Tregs can be derived from two sources, namely those developing within the thymus (whose contribution may therefore diminish with age) and those generated in the periphery. Thymically derived Tregs are thought to originate at the transition between the double-positive and single-positive stages following encounter between thymocytes that bear high affinity TCRs for self-peptide with their cognate antigens [165,187], but this assertion has been challenged recently by observations that thymic commitment to a Treg phenotype may occur at an earlier developmental stage [188]. The autoreactive Treg repertoire may be entrained by deletion following interaction with endogenous superantigens and APCs of both thymic and bone marrow origin [164], but the peripheral Treg repertoire retains a higher frequency of autospecific than alloreactive cells [164]. How Treg precursors commit to a Treg lineage in the thymus is unknown, but recent evidence points (in mice) to an interaction with a gene locus intimately linked with the MHC [189] (characterization of this locus and the genes involved is awaited) and may involve an important role for IL-2 signalling [190] and/or CD28 engagement [191].

Adults rendered temporarily lymphopenic have a greater propensity to develop autoimmune diseases [192,193]. Although this may reflect loss of a significant proportion of thymically derived Tregs (which are hard to regenerate given age-related thymic atrophy [194,195]) leading to loss of self-tolerance, one cannot ignore the fact that not everyone who is made lymphopenic develops autoimmune disease. One possibility is that the important determinant for maintenance of tolerance to self-components may be the relative frequency of effector cells to Tregs, as some chemotherapy agents have an equal effect on both [196]. However, depletion of CD25+ T cells from mice [197] or the adoptive transfer of naive T cells into lymphopenic recipients [198] is not sufficient for the development of autoimmune phenomena. The second possibility is that Tregs are generated in the periphery, an attractive notion that is supported by data showing reconstitution of the CD4+ CD25+ Treg population through conversion of CD4+ CD25– T cells [199,200]. Although this is not a robust phenomenon [12,157], there are suggestions that discrepancies may be the result of competition between CD4+ CD25– and CD4+ CD25+ T cells (i.e. that the rate of conversion is related to the relative frequency of the two cell types) [201] and that the number of Tregs may be linked to the availability of IL-2 (and, by inference, the number of IL-2-producing effector cells) [202]. Studies of human Treg populations have shown these populations to be highly proliferative and senescent in vivo with very short telomeres [203], which is consistent with their memory/CD45RO+ phenotype [140]. Their susceptibility to apoptosis and short telomeres (with low telomerase activity) means it is unlikely that they are capable of self-renewal; the more likely explanation is that Tregs are generated in the periphery.

Other studies have corroborated the importance of IL-2 for the development of Tregs[204] and are summarized in the review by Malek et al. [205]. Indeed, in an animal model of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) where autoreactive T cells from donors deficient in Tregs (DO11·10 Rag–/– animals) are infused into athymic antigen-expressing lymphopenic recipients (sOVA transgenic thymectomized, lethally irradiated mice reconstituted with Rag–/– bone marrow), development and recovery from disease is reliant upon generation of antigen-specific effector cells followed by de novo generation of peripheral Tregs in a concomitant, IL-2-dependent manner [206]. The added implication of these findings is that both functional effector cells and Tregs can develop in parallel from the same population of T cells in response to a single antigen in the periphery.

The mechanism(s) by which Tregs are generated in the periphery are unknown. However, there are indications that, in the same manner as with Th1/Th2 cell polarization, the antigenic stimulus (linked to the amount of antigen present as well as the strength of interaction) may determine the commitment to a Treg phenotype (low doses/weaker stimulus result in more Treg generation) [207,208]. The mode of antigen encounter, namely through (immature or suboptimally activated) dendritic cell presentation, also seems important for the conversion of naive T cells to a Treg phenotype [208,209], as may interactions with anti-inflammatory molecules such as thrombospondin-1 [210]. The demonstration that TGF-β-deficient mice have reduced numbers of peripheral [211,212] but not thymic Tregs[213] and that TGF-β assists the conversion of naive CD4+ CD25– T cells into Tregs both in vivo[209] and in vitro[214,215] argue in favour of the importance of this cytokine in the generation and maintenance of the peripheral Treg pool. The potential importance of these observations to human disorders will be discussed in the context of Th17 development below.

IL-17-producing cells

In mice, a discrete population of CD4+ helper T cells has been described as the predominant source of IL-17. These cells have been named Th17 cells. The initial basis of this nomenclature is the dichotomous effects of IL-12 and IL-23 (both members of the same family of IL-12 cytokines, sharing a common IL-12p40 subunit but differing second subunits, IL-12p35 and IL-12p19, respectively [216]) on the cytokine profile of CD4 cells. While IL-12 (signalling through signal transducer and activator of transcription, STAT-4) had been known to allow lineage commitment towards a Th1 phenotype producing IFN-γ as its signature cytokine (via the transcription factor T-bet[8,9]) [5,7,217] and inflammatory diseases had been viewed along the lines of a Th1/Th2 paradigm (e.g. IL-12p40 neutralization in mice ameliorates inflammatory diseases [218,219]), mice deficient in IFN-γ or IFN-γ signalling remained, paradoxically, susceptible to development of EAE and CIA [15,16]. Furthermore, IL-12p40 (lacking both IL-12 and IL-23) and IL-12p19 (lacking IL-23)-deficient mice were protected against EAE and CIA whereas IL-12p35 (IL-12)-deficient strains remained susceptible [220,221] suggesting that IL-23 rather than IL-12 was important in mediating the pathogenesis of these conditions. Shortly after these observations, it was reported that IL-23 stimulates production of IL-17 from a population of memory (but not naive) CD4+ T cells in a manner that does not exhibit elevation of IFN-γ[21,222] and that IL-17 is linked to the inflammation seen in CIA and EAE [20,21,72]. Further evidence that IL-17 was derived in mice from a discrete population of Th cells that were distinct from the Th1 lineage, termed Th17 cells, were provided by publications showing resistance of Th1 and Th2 cells in vitro to proliferation or production of IL-17 following stimulation with IL-23 and that development of IL-17-producing cells was inhibited by the presence of IFN-γ and/or IL-4 in the culture supernatant [223,224]. It has been proposed that production of IL-12 has greater importance for systemic responses and immunity to intracellular pathogens [225] while IL-23, produced from activated human macrophages and dendritic cells (DC) [226], has a more important role for mediating mucosal immune pathology through the promotion of Th1 and Th17 cytokine profiles, respectively [227].

It is now known that IL-6 [17–19] (see below), and not IL-23 [17,18], is critical for the induction of Th17 lineage commitment (which is supported by the fact that the IL-23 receptor is expressed exclusively on activated and memory T cells [222,228]), while IL-23 seems to be important for the selective expansion of these cells and production of IL-17 [229]. Indeed, other cytokines including IL-2, IL-15, IL-18 and IL-21 can also stimulate IL-17 production from (activated) human T cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) [226,229], while IL-12 potently inhibits it [229]. Development of Th17 cells is dependent upon correct co-stimulation (ICOS and CD28 [224]) and the absence of IFN-γ and IL-4, both of which are inhibitory [223]. Furthermore, Th17 lineage differentiation can be inhibited by the Th1-specific transcription factor T-bet in the context of IL-4 blockade [230] and is characterized by the expression of the orphan nuclear receptor RORγT[13]. Because IL-12 specifies lineage commitment to Th1 and has a stimulatory effect on IFN-γ secretion by Th1 cells [229], IL-12 may play a critically important role as a regulator of the balance between Th1 and Th17 responses. This assertion is supported by in vivo mouse data in which IL-23 and IL-12 had divergent pro- and anti-inflammatory roles in a model of collagen-induced arthritis [221]. It is important to state that, despite these observations, the description of discrete Th17 cells is mouse-specific and to date no committed Th17 cells have been demonstrated in humans.

Figure 2 shows the cytokine network that is thought to be important in the development and expansion of Th17 cells and the dichotomous Th1/Th17 cytokine profile engendered by these cytokines. Three recent papers have shed some light on the mechanisms by which naive precursor T cells commit to a Th17 phenotype in mice [17–19]. The first, a publication by Veldhoen et al., showed that naive CD4+ T cells could be skewed towards a Th17 phenotype in the presence of dendritic cells and Tregs in an inflammatory milieu (lipopolysaccharide stimulation) [18]. Absence of Tregs leads to Th1 differentiation, presumably through interaction of naive T cells with DCs producing IL-12. In the presence of Tregs and DC, the important drivers of Th17 differentiation were Treg-derived TGF-β and DC-derived IL-6, although both TNF-α and IL-1β (both DC-derived) also augmented the commitment to Th17. In this series of experiments, the IL-17-producing cells did not express T-bet or GATA-3 and addition of IL-12 and IL-4 or IL-18 inhibited Th17 development, but the most important determinant of commitment to a Th17 lineage was the presence of TGF-β, without requirement for cell-to-cell contact. These data were corroborated by Bettelli et al., who demonstrated using cells from a Foxp3-GFP knock-in mouse strain that differentiation towards Treg and Th17 phenotypes were mutually exclusive − activation of naive precursor cells using anti-CD3 in the presence of TGF-β lead to production of green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ cells (i.e. Tregs) as per previous observations, but activation in the presence of IL-6 in addition to TGF-β completely abrogated this and led to development of Th17 cells (that were GFP–). The differentiated cells were, respectively, functionally suppressive and inflammatory and development of the Th17 phenotype was independent of IL-23 [17]. The third paper, by Mangan et al. published simultaneously [19], showed that addition of TGF-β to naive CD4+ T cells resulted in the development of Th17 cells, an effect which was augmented in the presence of neutralizing antibodies to Th1 and Th2 polarizing cytokines (IL-4 and IFN-γ) or the use of CD4 cells from IFN-γ deficient animals [19]. Furthermore, they demonstrated that TGF-β up-regulated expression of the IL-23 receptor (which may explain the responsiveness of the Th17 population to IL-23). As before, supplementation of the culture conditions with exogenous IL-6 resulted in loss of all Foxp3+ cells, while blockade of IL-6 enhanced Treg development. Again, these findings point to mutually exclusive pathways for Th17 and Treg development based on the availability of TGF-β and IL-6. A schematic for naive T cell commitment is represented in Fig. 3. It should be noted, once again, that these data are derived from mice and whether this pathway exists in humans has not been determined.

Fig. 2.

Model of mouse helper T cell (Th) commitment to Th1, Th17 and T regulatory cell (Treg) phenotypes following encounter with antigen. Production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β by naturally occurring Tregs leads to lineage commitment of precursor helper T cells (Thp) towards Treg phenotypes. Stimulation of dendritic cells (DC) by microbial antigens causes production of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-23 and/or IL-12. Predominant production of IL-12 promotes commitment of Thp to a Th1 phenotype while IL-6, in combination with Treg-derived TGF-β promotes skewing of Thp towards a Th17 phenotype. IL-23 produced by DCs causes proliferation and cytokine production by Th17 cells.

Fig. 3.

T helper cell commitment towards specific lineages in mice. T helper cell precursors (Thp) can be skewed towards mutually exclusive Th1, Th2, Th17 and T regulatory cell (Treg) phenotypes on the basis of the cytokine environment. Presence of interleukin (IL)-12 promotes skewing towards Th1 commitment by signalling through signal transduction and activator of transcription (STAT)-4. Th1 cells are characterized by expression of T-bet and produce interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α. Th2 cell commitment is promoted by IL-4 via STAT-6 signalling. Th2 committed cells are characterized by expression of GATA-3. Development of Treg and Th17 phenotypes both require the presence of transforming growth factor-β but the presence of IL-6 preferentially skews the response towards a Th17 phenotype. Tregs are characterized in mice by expression of Foxp3.

A model for the regulation of T cell polarity in humans

Although the majority of the data concerning commitment to T cell lineages has been derived from mice, there is a clear difference in lineage differentiation based on the mode of stimulation and the cytokine milieu. The presence of discrete IL-17-producing cells in humans has yet to be confirmed; however, IL-17 is likely to be an important cytokine in the mediation of many inflammatory diseases and allograft rejection in humans. As such, one can propose a hypothesis with regard to the pathogenesis of autoimmune/inflammatory diseases and allograft rejection in humans that is based on extrapolations of the mouse data on the assumption that human cells exhibit discrete IL-17-producing populations and can be skewed towards different lineages.

Specifically, the observation that many inflammatory or autoimmune diseases present clinically as episodes of inflammation (flares), with periods of quiescence in between these episodes, argues for the presence of intervening periods of ‘equilibrium’ where the immune system displays tolerance to self-components (i.e. that proinflammatory components are ‘regulated’). During acute flares, a state of ‘disequilibrium’ ensues in which immune responses against self-components are dysregulated. The possibility arises that during these episodes Th cell phenotypes become skewed towards proinflamatory lineages (Th17 and Th1) (or that there is enhanced survival of these lineages) and away from anti-inflammatory phenotypes (Treg) on the basis of the local cytokine environment and DC populations. The mechanism of such a change could either be loss of skewing towards Treg phenotypes (with default towards Th1/Th17) or a primary shift towards the proinflammatory pathways. The central cytokine in this pathway, on the basis of the mouse data, may be IL-6, which is known to be elevated in most inflammatory conditions. Presumably, the balance is redressed during the recovery from flares and the equilibrium re-establishes itself. The part played by anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive drugs in the resolution phase and the effects of these drugs on specific subsets of T cells is not known at present.

Conclusions

Interleukin 17 is a pleiotropic cytokine with multiple proinflammatory functions that is likely to be involved in either the causation or progression of inflammatory diseases and transplant rejection in humans. Regulatory T cells are an anti-inflammatory lineage of T cells that are derived naturally from the thymus and also generated in the periphery on the basis of the local environment. It is possible that acute flares of autoimmune diseases or acute episodes of transplant rejection may be explained by a change in the relative dominance of these pathways in the periphery, either through preferential differentiation towards proinflammatory lineages or enhanced survival of these phenotypes. A change in the local polarizing conditions may be important in the skewing of these responses.

References

- 1.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Markovic-Plese S, Lacet B, Raus J, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Increased frequency of interleukin 2-responsive T cells specific for myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:973–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markovic-Plese S, Fukaura H, Zhang J, et al. T cell recognition of immunodominant and cryptic proteolipid protein epitopes in humans. J Immunol. 1995;155:982–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, et al. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2593–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constant SL, Bottomly K. Induction of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approaches. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelms K, Keegan AD, Zamorano J, Ryan JJ, Paul WE. The IL-4 receptor: signaling mechanisms and biologic functions. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:701–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gately MK, Renzetti LM, Magram J, et al. The interleukin-12/interleukin-12-receptor system: role in normal and pathologic immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:495–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nature Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Identifying Foxp3-expressing suppressor T cells with a bicistronic reporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5126–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liblau RS, Singer SM, McDevitt HO. Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol Today. 1995;16:34–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthys P, Vermeire K, Mitera T, Heremans H, Huang S, Billiau A. Anti-IL-12 antibody prevents the development and progression of collagen-induced arthritis in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2143–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199807)28:07<2143::AID-IMMU2143>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferber IA, Brocke S, Taylor-Edwards C, et al. Mice with a disrupted IFN-gamma gene are susceptible to the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J Immunol. 1996;156:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T (H) 17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, van de Loo FA, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls J, van den Berg WB. Overexpression of IL-17 in the knee joint of collagen type II immunized mice promotes collagen arthritis and aggravates joint destruction. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:102–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02684010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouvier E, Luciani MF, Mattei MG, Denizot F, Golstein P. CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a herpesvirus saimiri gene. J Immunol. 1993;150:5445–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao Z, Timour M, Painter S, Fanslow W, Spriggs M. Complete nucleotide sequence of the mouse CTLA8 gene. Gene. 1996;168:223–5. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Chen J, Huang A, et al. Cloning and characterization of IL-17B and IL-17C, two new members of the IL-17 cytokine family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:773–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starnes T, Broxmeyer HE, Robertson MJ, Hromas R. Cutting edge: IL-17D, a novel member of the IL-17 family, stimulates cytokine production and inhibits hemopoiesis. J Immunol. 2002;169:642–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Ho WH, Maruoka M, et al. IL-17E, a novel proinflammatory ligand for the IL-17 receptor homolog IL-17Rh1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1660–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starnes T, Robertson MJ, Sledge G, et al. Cutting edge: IL-17F, a novel cytokine selectively expressed in activated T cells and monocytes, regulates angiogenesis and endothelial cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 2001;167:4137–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Y, Ullrich SJ, Zhang J, et al. A novel cytokine receptor-ligand pair. Identification, molecular characterization, and in vivo immunomodulatory activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19167–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910228199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, et al. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995;3:811–21. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferretti S, Bonneau O, Dubois GR, Jones CE, Trifilieff A. IL-17, produced by lymphocytes and neutrophils, is necessary for lipopolysaccharide-induced airway neutrophilia: IL-15 as a possible trigger. J Immunol. 2003;170:2106–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockhart E, Green AM, Flynn JL. IL-17 production is dominated by gammadelta T cells rather than CD4 T cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:4662–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin HC, Benbernou N, Esnault S, Guenounou M. Expression of IL-17 in human memory CD45RO+ T lymphocytes and its regulation by protein kinase A pathway. Cytokine. 1999;11:257–66. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molet S, Hamid Q, Davoine F, et al. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:430–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Q, Desta T, Fenton M, Graves DT, Amar S. Cytokine profiling of macrophages exposed to Porphyromonas gingivalis, its lipopolysaccharide, or its FimA protein. Infect Immun. 2005;73:935–43. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.935-943.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao Z, Spriggs MK, Derry JM, et al. Molecular characterization of the human interleukin (IL)-17 receptor. Cytokine. 1997;9:794–800. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva WA, Jr, Covas DT, Panepucci RA, et al. The profile of gene expression of human marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:661–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-6-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haudenschild D, Moseley T, Rose L, Reddi AH. Soluble and transmembrane isoforms of novel interleukin-17 receptor-like protein by RNA splicing and expression in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4309–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moseley TA, Haudenschild DR, Rose L, Reddi AH. Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:155–74. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakae S, Komiyama Y, Nambu A, et al. Antigen-specific T cell sensitization is impaired in IL-17-deficient mice, causing suppression of allergic cellular and humoral responses. Immunity. 2002;17:375–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attur MG, Patel RN, Abramson SB, Amin AR. Interleukin-17 up-regulation of nitric oxide production in human osteoarthritis cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1050–3. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, et al. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2559–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albanesi C, Cavani A, Girolomoni G. IL-17 is produced by nickel-specific T lymphocytes and regulates ICAM-1 expression and chemokine production in human keratinocytes: synergistic or antagonist effects with IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1999;162:494–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witowski J, Pawlaczyk K, Breborowicz A, et al. IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO alpha chemokine from mesothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5814–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woltman AMHS, Boonstra JG, Gobin SJ, van Daha MR, van Kooten C. Interleukin-17 and CD40-ligand synergistically enhance cytokine and chemokine production by renal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:2044–55. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyamoto M, Prause O, Sjostrand M, Laan M, Lotvall J, Linden A. Endogenous IL-17 as a mediator of neutrophil recruitment caused by endotoxin exposure in mouse airways. J Immunol. 2003;170:4665–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye P, Garvey PB, Zhang P, et al. Interleukin-17 and lung host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:335–40. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.3.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laan M, Lotvall J, Chung KF, Linden A. IL-17-induced cytokine release in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro: role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:200–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones CE, Chan K. Interleukin-17 stimulates the expression of interleukin-8, growth-related oncogene-alpha, and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor by human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:748–53. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao Z, Painter SL, Fanslow WC, et al. Human IL-17: a novel cytokine derived from T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:5483–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGeachy MJ, Anderton SM. Cytokines in the induction and resolution of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cytokine. 2005;32:81–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarzenberger P, La RV, Miller A, et al. IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis in mice: use of an alternate, novel gene therapy-derived method for in vivo evaluation of cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:6383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan G, French D, Mao W, et al. Forced expression of murine IL-17E induces growth retardation, jaundice, a Th2-biased response, and multiorgan inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:6559–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miossec P. Interleukin-17 in rheumatoid arthritis: if T cells were to contribute to inflammation and destruction through synergy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:594–601. doi: 10.1002/art.10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, et al. IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1345–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hwang SY, Kim HY. Expression of IL-17 homologs and their receptors in the synovial cells of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mol Cells. 2005;19:180–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chabaud M, Durand JM, Buchs N, et al. Human interleukin-17: a T cell-derived proinflammatory cytokine produced by the rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:963–70. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<963::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chabaud M, Lubberts E, Joosten L, van Den BW, Miossec P. IL-17 derived from juxta-articular bone and synovium contributes to joint degradation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:168–77. doi: 10.1186/ar294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chabaud M, Fossiez F, Taupin JL, Miossec P. Enhancing effect of IL-17 on IL-1-induced IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes and its regulation by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katz Y, Nadiv O, Beer Y. Interleukin-17 enhances tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced synthesis of interleukins 1,6, and 8 in skin and synovial fibroblasts: a possible role as a ‘fine–tuning cytokine’ in inflammation processes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2176–84. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2176::aid-art371>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LeGrand A, Fermor B, Fink C, et al. Interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-17 synergistically up-regulate nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production in explants of human osteoarthritic knee menisci. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2078–83. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2078::AID-ART358>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, van de Loo FA, van den Gersselaar LA, van den Berg WB. Reduction of interleukin-17-induced inhibition of chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis in intact murine articular cartilage by interleukin-4. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1300–6. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6<1300::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jovanovic DV, Di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, et al. Modulation of TIMP-1 synthesis by antiinflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2 in interleukin 17 stimulated human monocytes/macrophages. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:712–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jovanovic DV, Martel-Pelletier J, Di Battista JA, et al. Stimulation of 92-kd gelatinase (matrix metalloproteinase 9) production by interleukin-17 in human monocyte/macrophages: a possible role in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1134–44. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1134::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chabaud M, Garnero P, Dayer JM, Guerne PA, Fossiez F, Miossec P. Contribution of interleukin 17 to synovium matrix destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine. 2000;12:1092–9. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chevrel G, Garnero P, Miossec P. Addition of interleukin 1 (IL1) and IL17 soluble receptors to a tumour necrosis factor alpha soluble receptor more effectively reduces the production of IL6 and macrophage inhibitory protein-3alpha and increases that of collagen in an in vitro model of rheumatoid synoviocyte activation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:730–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van bezooijen RL, Farih-Sips HC, Papapoulos SE, Lowik CW. Interleukin-17: a new bone acting cytokine in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1513–21. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.9.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chabaud M, Page G, Miossec P. Enhancing effect of IL-1, IL-17, and TNF-alpha on macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha production in rheumatoid arthritis: regulation by soluble receptors and Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2001;167:6015–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakae S, Saijo S, Horai R, Sudo K, Mori S, Iwakura Y. IL-17 production from activated T cells is required for the spontaneous development of destructive arthritis in mice deficient in IL-1 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5986–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1035999100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:6173–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoshino H, Laan M, Sjostrand M, Lotvall J, Skoogh BE, Linden A. Increased elastase and myeloperoxidase activity associated with neutrophil recruitment by IL-17 in airways in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:143–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Happel KI, Zheng M, Young E, et al. Cutting edge: roles of Toll-like receptor 4 and IL-23 in IL-17 expression in response to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J Immunol. 2003;170:4432–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, et al. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol. 1999;162:2347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Kuga H, et al. Modulation of bronchial epithelial cells by IL-17. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:804–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rahman MS, Yamasaki A, Yang J, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17A induces eotaxin-1/CC chemokine ligand 11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of MAPK (Erk1/2, JNK, P38) pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:4064–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laan M, Palmberg L, Larsson K, Linden A. Free, soluble interleukin-17 protein during severe inflammation in human airways. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:534–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00280902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barczyk A, Pierzchala W, Sozanska E. Interleukin-17 in sputum correlates with airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. Respir Med. 2003;97:726–33. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2003.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hellings PW, Kasran A, Liu Z, et al. Interleukin-17 orchestrates the granulocyte influx into airways after allergen inhalation in a mouse model of allergic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:42–50. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jatakanon A, Uasuf C, Maziak W, Lim S, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1532–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9806170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bank U, Reinhold D, Kunz D, et al. Effects of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) on neutrophil elastase release. Inflammation. 1995;19:83–99. doi: 10.1007/BF01534383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Skold CM, Liu X, Umino T, et al. Human neutrophil elastase augments fibroblast-mediated contraction of released collagen gels. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1138–46. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9805033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suzuki T, Wang W, Lin JT, Shirato K, Mitsuhashi H, Inoue H. Aerosolized human neutrophil elastase induces airway constriction and hyperresponsiveness with protection by intravenous pretreatment with half-length secretory leukoprotease inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1405–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bank U, Kupper B, Reinhold D, Hoffmann T, Ansorge S. Evidence for a crucial role of neutrophil-derived serine proteases in the inactivation of interleukin-6 at sites of inflammation. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:235–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen Y, Thai P, Zhao YH, Ho YS, DeSouza MM, Wu R. Stimulation of airway mucin gene expression by interleukin (IL)-17 through IL-6 paracrine/autocrine loop. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17036–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Merville P, Pouteil-Noble C, Wijdenes J, Potaux L, Touraine JL, Banchereau J. Detection of single cells secreting IFN-gamma, IL-6, and IL-10 in irreversibly rejected human kidney allografts, and their modulation by IL-2 and IL-4. Transplantation. 1993;55:639–46. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199303000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Merville P, Pouteil-Noble C, Wijdenes J, Potaux L, Touraine JL, Banchereau J. Cells infiltrating rejected human kidney allografts secrete IFN-gamma, IL-6, and IL-10, and are modulated by IL-2 and IL-4. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:111–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pavlakis M, Strehlau J, Lipman M, Shapiro M, Maslinski W, Strom TB. Intragraft IL-15 transcripts are increased in human renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1996;62:543–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199608270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Loong CC, Hsieh HG, Lui WY, Chen A, Lin CY. Evidence for the early involvement of interleukin 17 in human and experimental renal allograft rejection. J Pathol. 2002;197:322–32. doi: 10.1002/path.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van KC, Boonstra JG, Paape ME, et al. Interleukin-17 activates human renal epithelial cells in vitro and is expressed during renal allograft rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1526–34. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V981526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hsieh HG, Loong CC, Lin CY. Interleukin-17 induces src/MAPK cascades activation in human renal epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2002;19:159–74. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Wuyts WA, et al. The role of interleukin-17 during acute rejection after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:779–87. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00019405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoshida S, Haque A, Mizobuchi T, et al. Anti-type V collagen lymphocytes that express IL-17 and IL-23 induce rejection pathology in fresh and well-healed lung transplants. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:724–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li J, Simeoni E, Fleury S, et al. Gene transfer of soluble interleukin-17 receptor prolongs cardiac allograft survival in a rat model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:779–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tang JL, Subbotin VM, Antonysamy MA, Troutt AB, Rao AS, Thomson AW. Interleukin-17 antagonism inhibits acute but not chronic vascular rejection. Transplantation. 2001;72:348–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Antonysamy MA, Fanslow WC, Fu F, et al. Evidence for a role of IL-17 in organ allograft rejection: IL-17 promotes the functional differentiation of dendritic cell progenitors. J Immunol. 1999;162:577–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wong CK, Ho CY, Li EK, Lam CW. Elevation of proinflammatory cytokine (IL-18, IL-17, IL-12) and Th2 cytokine (IL-4) concentrations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:589–93. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediat Inflammation. 2005;2005:273–9. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Homey B, eu-Nosjean MC, Wiesenborn A, et al. Up-regulation of macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha/CCL20 and CC chemokine receptor 6 in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2000;164:6621–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matusevicius D, Kivisakk P, He B, et al. Interleukin-17 mRNA expression in blood and CSF mononuclear cells is augmented in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1999;5:101–4. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kurasawa K, Hirose K, Sano H, et al. Increased interleukin-17 production in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2455–63. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2455::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fujino S, Andoh A, Bamba S, et al. Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2003;52:65–70. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Biesinger B, Muller-Fleckenstein I, Simmer B, et al. Stable growth transformation of human T lymphocytes by herpesvirus saimiri. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3116–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Patera AC, Pesnicak L, Bertin J, Cohen JI. Interleukin 17 modulates the immune response to vaccinia virus infection. Virology. 2002;299:56–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knappe A, Hiller C, Niphuis H, et al. The interleukin-17 gene of herpesvirus saimiri. J Virol. 1998;72:5797–801. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5797-5801.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Luzza F, Parrello T, Monteleone G, et al. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J Immunol. 2000;165:5332–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chung DR, Kasper DL, Panzo RJ, et al. CD4+ T cells mediate abscess formation in intra-abdominal sepsis by an IL-17-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:1958–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnson RB, Wood N, Serio FG. Interleukin-11 and IL-17 and the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2004;75:37–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tartour E, Fossiez F, Joyeux I, et al. Interleukin 17, a T-cell-derived cytokine, promotes tumorigenicity of human cervical tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Numasaki M, Fukushi J, Ono M, et al. Interleukin-17 promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Blood. 2003;101:2620–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Benchetrit F, Ciree A, Vives V, et al. Interleukin-17 inhibits tumor cell growth by means of a T-cell-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2002;99:2114–21. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hirahara N, Nio Y, Sasaki S, et al. Reduced invasiveness and metastasis of Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with human interleukin-17 gene. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kato T, Furumoto H, Ogura T, et al. Expression of IL-17 mRNA in ovarian cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:735–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Steiner GE, Newman ME, Paikl D, et al. Expression and function of pro-inflammatory interleukin IL-17 and IL-17 receptor in normal, benign hyperplastic, and malignant prostate. Prostate. 2003;56:171–82. doi: 10.1002/pros.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ciree A, Michel L, Camilleri-Broet S, et al. Expression and activity of IL-17 in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome) Int J Cancer. 2004;112:113–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wrobel T, Mazur G, Jazwiec B, Kuliczkowski K. Interleukin-17 in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cell Mol Med. 2003;7:472–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Numasaki M, Watanabe M, Suzuki T, et al. IL-17 enhances the net angiogenic activity and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice through promoting CXCR-2-dependent angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175:6177–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Grazia Roncarolo M, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Weiner HL. Induction and mechanism of action of transforming growth factor-beta-secreting Th3 regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:207–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lu L, Werneck MBF, Cantor H. The immunoregulatory effects of Qa-1. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:51–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cortesini R, LeMaoult J, Ciubotariu R, Cortesini NSF. CD8+CD28- T suppressor cells and the induction of antigen-specific, antigen-presenting cell-mediated suppression of Th reactivity. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:201–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rifa'i M, Kawamoto Y, Nakashima I, Suzuki H. Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1123–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hanninen A, Harrison LC. Gamma delta T cells as mediators of mucosal tolerance: the autoimmune diabetes model. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:109–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang C, Zhang J, Tian ZG. The regulatory effect of natural killer cells: do ‘NK-reg cells’ exist? Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:241–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yu G, Xu X, Vu MD, Kilpatrick ED, Li XC. NK cells promote transplant tolerance by killing donor antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1851–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:652–62. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ariel A, Fredman G, Sun YP, et al. Apoptotic neutrophils and T cells sequester chemokines during immune response resolution through modulation of CCR5 expression. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1209–16. doi: 10.1038/ni1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Liu J, Liu Z, Witkowski P, et al. Rat CD8+ FOXP3+ T suppressor cells mediate tolerance to allogeneic heart transplants, inducing PIR-B in APC and rendering the graft invulnerable to rejection. Transpl Immunol. 2004;13:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Suciu-Foca N, Manavalan JS, Scotto L, et al. Molecular characterization of allospecific T suppressor and tolerogenic dendritic cells: review. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Liu Z, Tugulea S, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Specific suppression of T helper alloreactivity by allo-MHC class I-restricted CD8+ Int Immunol. 1998;10:775–83. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kapp JA, Honjo K, Kapp LM, Xu XY, Cozier A, Bucy RP. TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells activated in the presence of TGF{beta} express FoxP3 and mediate linked suppression of primary immune responses and cardiac allograft rejection. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1549–62. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhang ZX, Young K, Zhang L. CD3+CD4-CD8- alphabeta-TCR+ T cell as immune regulatory cell. J Mol Med. 2001;79:419–27. doi: 10.1007/s001090100238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhang ZX, Yang L, Young KJ, DuTemple B, Zhang L. Identification of a previously unknown antigen-specific regulatory T cell and its mechanism of suppression. Nat Med. 2000;6:782–9. doi: 10.1038/77513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sakaguchi S, Toda M, Asano M, Itoh M, Morse SS, Sakaguchi N. T cell-mediated maintenance of natural self-tolerance: its breakdown as a possible cause of various autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:211–20. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chatila TA, Blaeser F, Ho N, et al. JM2, encoding a fork head-related protein, is mutated in X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:R75–R81. doi: 10.1172/JCI11679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wildin RS, Ramsdell F, Peake J, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet. 2001;27:18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dieckmann D, Plottner H, Berchtold S, Berger T, Schuler G. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4(+) CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1303–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, Tuettenberg A, Knop J, Enk AH. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4(+) CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1285–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wing K, Lindgren S, Kollberg G, et al. CD4 T cell activation by myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is suppressed by adult but not cord blood CD25+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:579–87. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. Human regulatory T cells and their role in autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:203–16. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. The regulation of allergy and asthma. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:238–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Rouse BT, Sarangi PP, Suvas S. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:272–86. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Belkaid Y, Blank RB, Suffia I. Natural regulatory T cells and parasites: a common quest for host homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:287–300. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Waldmann H, Adams E, Fairchild P, Cobbold S. Infectious tolerance and the long-term acceptance of transplanted tissue. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:301–13. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells suppress systemic and mucosal immune activation to control intestinal inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:256–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:266–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]