Abstract

Recent functional research studies suggest an anti-fibrotic role for natural killer (NK) cells coupled with a profibrotic role for CD8 cells. However, the morphological cellular interplay between the different cell types is less clear. To investigate lymphocyte/hepatic stellate cell (HSC) interactions, hepatic fibrosis was induced by administering carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) intraperitoneally (i.p.) for 4 weeks in C57Bl/6 mice. Animals were killed at 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks. Liver sections were stained for Sirius red. Confocal microscopy was used to evaluate alpha smooth-muscle actin (αSMA) and lymphocyte subsets in liver sections. At weeks 0 and 4, liver protein extracts were assessed for αSMA by Western blotting and isolated liver lymphocytes as well as HSC were analysed by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS). Similar to the results obtained from classical Sirius red staining and αSMA blotting, analysis of liver sections by confocal microscopy revealed a marked and continuous accumulation of αSMA staining along sequential experimental check-points after administering CCl4. Although the number of all liver lymphocyte subsets increased following fibrosis induction, FACS analysis revealed an increase in the distribution of liver CD8 subsets and a decrease of CD4 T cells. Confocal microscopy showed a significant early appearance of CD8 and NK cells, and to a lesser extent CD4 T cells, appearing only from week 2. Lymphocytes were seen in proximity only to HSC, mainly in the periportal area and along fibrotic septa, suggesting a direct interaction. Notably, lymphocyte subsets were undetectable in naive liver sections. Freshly isolated HCS show high expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and CD11c. In the animal model of hepatic fibrosis, lymphocytes infiltrate into the liver parenchyma and it is thought that they attach directly to activated HSC. Because HSCs express CD11c/class II molecules, interactions involving them might reflect that HSCs have an antigen-presenting capacity.

Keywords: CD4, CD8, confocal, hepatic fibrosis, lymphocytes, NK, stellate cells

Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is the result of chronic liver injury, regardless of aetiology, during which hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) proliferate and differentiate into matrix-producing cells [1,2]. Portal fibroblasts and non-HSC myofibroblasts were also reported recently in fibrogenesis [3]. The activity of stellate cells is influenced by an array of cytokines, some of which are profibrotic, i.e. transforming growth factor (TGF)-α1 [4]), whereas others play an anti-fibrotic role, i.e. interleukin (IL)-10 [5,6] and interferon (IFN)-γ [7]). T helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes, expressing high levels of anti-fibrosis cytokines such as IFN-γ, have an anti-fibrotic role [5,7], whereas the Th2 lymphocytes, expressing high levels of profibrosis cytokines such as IL-4, have a profibrotic role [8], in such a manner that the Th1 : Th2 ratio can tilt the balance towards or away from fibrosis [9,10].

Different inflammatory cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and T lymphocytes, play a role in orchestrating pro- and anti-fibrotic stimuli. The role of increased CD8 and decreased CD4 lymphocyte subsets in mediating hepatic fibrosis has been reported previously to be attenuated by IL-10 [10]. By generating a transgenic mouse secreting rat IL-10 (rIL-10) in hepatocytes, we assessed the effect of sustained local expression of the cytokine on hepatic fibrogenesis. rIL-10 was found to have an anti-fibrotic effect; it also reduced the number of CD8 lymphocytes. The functional interaction between lymphocytes and HSC was shown using the adaptive transfer model of hepatic fibrosis. The fibrogenic activity of CD8 lymphocytes was confirmed when they were transferred from a fibrotic donor to severe combined immune-deficient (SCID) mice. CD4 T cells, however, were shown to decrease following fibrosis induction. On the other hand, in the adoptive transfer model, CD4 T cells induced slightly more fibrosis than seen in the CD8 subsets [11]. Furthermore, NK cells were shown functionally to have an anti-fibrotic effect [12]. These findings significantly broaden our understanding of immune mediation of fibrosis and point to the manipulation of the CD4, CD8 and NK subsets as a potential means of therapeutically modulating fibrosis.

Based on our earlier functional results of lymphocyte–HSC interactions [11,12], we attempted to evaluate the morphological cellular interactions between HSC and the lymphocyte subsets in an animal model of hepatic fibrosis in vivo. Except for the known orchestration among cytokines and other mediators, it is not yet known whether close HSC–lymphocyte interaction is mandatory. To address this issue, a carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) model of hepatic fibrosis was induced in wild-type (WT) mice with a C57/bL6 background, and liver lymphocytes were analysed in situ by confocal microscopy at sequential time check-points.

Materials and methods

Animals

Twelve-week-old male C57/black6 mice (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) were used. Animals were housed in a barrier facility and cared for according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines. The animal procedures were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hepatic fibrosis model

Fibrosis was induced by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4; Sigma, Cream Ridge, NJ, USA, C-5331) at 0·5 µl pure CCl4/g body weight, twice weekly for 4 weeks [11] in WT mice. Following ketamine/xylazine anaesthesia, four fibrotic mice were killed sequentially at weeks 1, 2 and 3, consecutively. At week 4, eight fibrotic mice were killed in parallel to eight naive mice. The fibrotic group included a total of 20 animals.

Fibrosis induction

To obtain empirical evidence of fibrosis induction at week 4 of our experiment, the posterior third of the liver was fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h and then paraffin-embedded in an automated tissue processor; 7-mm liver sections were cut from each animal. Sections (15 µm) were then stained in 0·1% Sirius red F3B in saturated picric acid (both from Sigma) [11]. Additionally, immunoblot analysis of alpha smooth-muscle actin (αSMA) in liver extracts was performed as described previously [11], with modifications. Briefly, whole-liver protein extracts were prepared in liver homogenization buffer [50 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7·6), 0·25% Triton-X 100, 0·15 M NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2 and complete mini-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany)]. Next, proteins (30 µg per lane) were resolved on a 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel (Novex, Groningen, the Netherlands) under reducing conditions. For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to a Protran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C in a blocking buffer containing 5% skimmed milk and then incubated with an anti-SMA mouse monoclonal antibody (Dako, Denmark, cat. no. M0851), diluted 1/2000, maintained for 2 h at room temperature, and subsequently with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (PARIS, Compiègne, France) diluted 1/10,000, then maintained for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was revealed by enhanced (ECL) using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Les Ulis, France).

Cell isolation, staining and flow cytometric analysis

Intrahepatic lymphocytes were isolated by perfusion of the liver with digestion buffer [3 ml medium (in 1 min) containing collagenase (2 mg/10 ml) and DNAse I (0·2 mg/10 ml) at 37°C]. After perfusion, the liver was homogenized with an additional 10 ml of digestion buffer and completed to 40 ml by RPMI-1640 + 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and then incubated under constant shaking (hot shaker; 1 cycle/s) at 37°C for 30 min. The digested liver cell suspension was centrifuged at 30 g for 3 min at 4°C to remove hepatocytes and cell clumps. The supernatant was then centrifuged to obtain a pellet of cells free of hepatocytes, to a final volume of 1 ml. Lymphocytes were then isolated from this cell suspension using 24% metrizamide gradient separation. Cells were adjusted to 2 × 107/ml in staining buffer (in saline containing 1% bovine albumin). Fifty µl of the cell suspension was incubated with antibodies on ice for 30 min, washed with staining buffer and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) data were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), set to capture all events. Antibodies used for staining were mouse anti-CD4, CD8, CD3, CD45 and pan-NK antibodies, conjugated by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) and allophycocyanin (APC), respectively. Antibodies were purchased from Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, Transduction Laboratories. FACS data were analysed using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) [11].

Hepatic stellate cell isolation

HSCs were isolated from naive and fibrotic C57BL/6 mice using sequential pronase/collagenase digestion followed by Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation, as described previously in rats [13,14]. Following anaesthesia and abdominal exploration, liver perfusion was performed via the portal vein with 20 ml modified Eagle's medium (MEM) (Gibco/BRL, UK) to obtain hepatic washout. Perfusion was then followed by 10 ml of Dulbecco's MEM (DMEM)/F-12 (Gibco/BRL, Germany) containing 0·5 mg Pronase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH; cat. no. 1459643) per gram body weight of the mouse, followed by 10 ml of DMEM/F-12 containing 7 mg liberase enzyme 3 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH; cat. no. 1814184). The digested liver was mashed ex vivo and incubated at 37°C for 25 min in 50 ml of DMEM/F-12 solution containing 0·05% Pronase and 20 µg/ml of Dnase-I (Roche Diagnostics GmbH; cat. no. 1284932). The resulting suspension was filtered through a 150-µm steel mesh and centrifuged on an 8·2% Nycodenz (Sigma; cat. no. D-2158) cushion at 1400 g for 15 min, which produced a stellate cell-enriched fraction in the upper whitish layer. Samples were stored at 4°C until the FACS analysis was performed. Freshly isolated HSC were stained simultaneously by Cy-5-conjugated anti-αSMA antibodies to purified HSC, PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD45 antibodies to exclude contaminated lymphocytes, FITC rat anti-mouse class II and APC rat anti-mouse CD11c antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

Liver biopsies from all check-points were incubated overnight at room temperature with isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 10% sucrose and 4% formaldehyde solution. Specimens were frozen at −80°C and 7 μm-thick frozen sections were prepared using cryostat (Leica CM 3000, TX, USA). Cellular hyperpermeability was achieved using the 0·2% Triton (Sigma). One per cent bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used to block non-specific background staining. Following PBS washing, slides were incubated with primary antibody to lymphocyte markers and anti-αSMA mouse monoclonal primary antibody (Dako, cat. no. M0851) at a dilution of 1 : 40 for 45 min at room temperature in the dark, and washed three times with PBS. The secondary antibody Cy-5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was then added, followed by three PBS washes. In each double-stained set, a single lymphocyte subset was stained with the anti-αSMA. PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD45 antibody was used as a pan-lymphocyte marker. FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD49b/Pan-NK cell monoclonal antibody, identifying the majority of NK cells, was used. Rat anti-mouse CD4 and CD8 antibodies were conjugated to FITC and PE, respectively. To maintain staining and prevent fluorescent bleaching, sections were stacked and covered with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham AL, USA). A nucleus marker 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) was included within Fluoromount-G (UltraCruz™ mounting medium [Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA] with DAPI). Sections were then stored at 4°C until they were analysed by by confocal microscopy [3,15].

Confocal microscopy and image capture

A confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 M; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) was used to analyse the stained sections; it was equipped with a triple band pass filter and showed three-dimensional imaging [16]. Grey-scale images were collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Quantix Corp., Cambridge, MA, USA) and analysed using Smart-capture software (Carl Zeiss Microscope Systems LSM, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.). Fifty images were collected from each liver with a charge-coupled device camera (Hall 100) and analysed with Zeiss LSM Image Browser software. Image processing was performed using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems UK, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK) [17].

Quantification of the relative area

The relative area of stained αSMA, CD4, CD8 and NK cells (expressed as the percentage of total liver area) was assessed by analysing 50 stained liver sections per animal. Four animals were included in each group. Each field was acquired at 10× magnification and then analysed at the specific channel using a computerized morphometry system. The measured relative area was divided by the field area and then multiplied by 100. The results are presented as the mean relative area ± standard deviation (s.d.).

Statistical analysis

FACS analysis was used for statistically significant differences by Student's t-test. Results of confocal microscopy were correlated between naive and fibrotic animals qualitatively from all time-points and were confirmed in four repeated animals at each time-point (0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks).

Results

CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis and liver injury

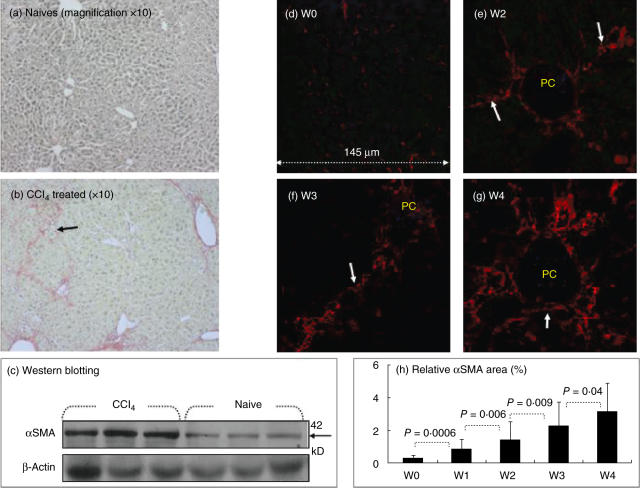

All animals survived the 4 weeks of observation after the CCl4 treatment. The extent of fibrosis was determined in naive and fibrotic mice using the classical Sirius red stain. Fibrotic septa were well established in fibrotic animals (Fig. 1b) compared with naive animals (Fig. 1a). To confirm the finding of increased fibrosis, the expression of αSMA (a marker of stellate cell activation) was evaluated in liver protein extracts. Increased fibrosis, as indicated by an increase in the Sirius red stain, is associated with increased expression of αSMA, as assessed by immunoblotting, indicating increased stellate cell activation (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Increased fibrosis in the animal post-carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) model of liver injury. Following fibrosis induction for 4 weeks tissue sections were stained with Sirius red, as described in Materials and methods. Representative tissue sections from naive and fibrotic animals are shown (a,b, respectively). Fibrotic septa that are well established in fibrotic animals are highlighted by arrows (magnification 10×). Whole-liver protein lysates were extracted and 30 µg total proteins was loaded per lane and analysed for alpha smooth-muscle actin (αSMA) and beta-actin expression (Fig. 1c). Beta-actin expression (lower lane) was similar in all tested wells. Increased αSMA expression (upper lane) was found in lysates of fibrotic mice receiving CCl4, compared with naive animals. The findings are representative of at least four different experiments with the same number of eight animals in each subgroup. (d–g) Confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to visualize stained sections as described in Materials and methods, with a × 40 lens. Liver biopsies from fibrotic (e–g) but not naive animals (d) were stained with primary antibodies to αSMA. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) (white arrows) were stained as small red cells. αSMA staining increased throughout CCl4 administration, as was demonstrated with growing septal formation at weeks 2 (e), 3 (f) and 4 (g). PC = portal space. The findings are representative of two different experiments with four animals in each time subgroup. The relative area of stained αSMA cells (expressed as the percentage of total liver area) was assessed by analysing 50 stained liver sections per animal (h). Each field was acquired at 10 × magnification and then analysed at the specific channel using a computerized morphometry system. The measured relative area was divided by the field area and then multiplied by 100. Results are presented as the mean relative area of all animal groups ± s.d. (h) Increased relative area of αSMA following fibrosis induction, as described in Materials and methods.

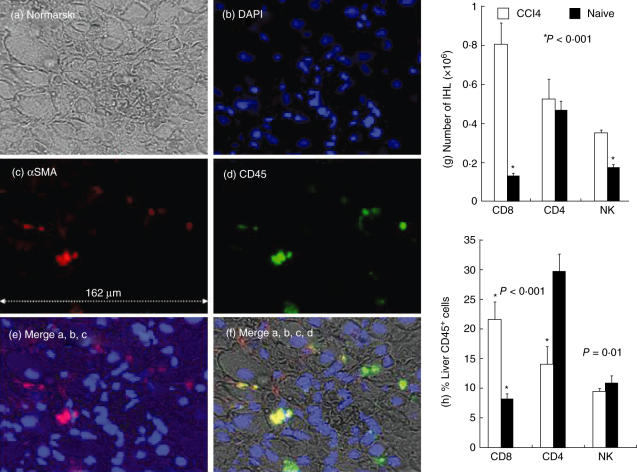

Liver sections were then analysed by confocal microscopy with Cy-5 anti-αSMA staining. None of the naive animals showed abnormal αSMA staining (Fig. 1d), except for a light staining observed normally along blood vessels. Following CCl4 induction, however, activated HSCs stain positively with Cy-5 anti-αSMA and appear in situ as small red cells adjacent to hepatocytes (white arrows, Fig. 1e–g). Although αSMA-positive cells might include myofibroblasts and vascular cells, it is still a gold standard in the staining of HSC [3]. The αSMA signal showed a marked increase, continuous accumulation and growing septal formation along all checked time-points (Fig. 1e–g). The measured relative αSMA area is 0·26% ± 0·19 in naive animals (Fig. 1h), which increases significantly following CCl4 injections, to 0·83 ± 0·59 in the first week (P = 0·0006), 1·44 ± 1·1 in the second week (P = 0·006), 2·3 ± 1·4 in the third week (P = 0·009) and 3·14 ± 1·7 in the fourth week (P = 0·04). To visualize liver architecture and orientation more clearly, DAPI was introduced (Fig. 2, lens 60). Figure 2 illustrates a sample from the first fibrosis week with triple-stained αSMA in red, DAPI in blue and PE-conjugated anti-CD45 as a pan-lymphocyte marker in the green laser. Figure 2a shows the whole liver architecture. Single DAPI-stained nuclei, αSMA or CD45 are shown separately in Fig. 2b,c,d, respectively. Merged figures in Fig. 2e,f are showing overlaying stains. The yellow-coloured cells in Fig. 3e are a result of the green and red mixture, reflecting the overlay and attachment of lymphocytes and HSCs to each other.

Fig. 2.

Architecture of liver showing hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) to lymphocyte proximity: to enhance liver architecture visualization and orientation, a nucleus marker 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) was introduced (lens 60). A sample from the first fibrosis week illustrates triple staining of αSMA in red, DAPI in blue and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD45 as a pan-lymphocyte marker in the green laser. (a) Whole-liver architecture, as demonstrated in Nomarsky. Single DAPI-stained nuclei, αSMA or CD45 are shown separately in (b–d), respectively. Merged figures in (e,f) show overlaying stains. The yellow-coloured cells in (e) are a mixed result of the green and red, reflecting the overlay and attachment of lymphocytes and HSCs to each other. The findings are representative of two different experiments with four animals in each time subgroup. Intrahepatic lymphocytes (IHL) were isolated from naive and 4-week-old fibrotic mice. Isolated cells were counted (g,h), stained and analysed by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS), as detailed in Materials and methods. All lymphocyte subsets showed an increase in number following fibrosis induction (g). Compared to naive animals (filled bars), FACS analysis of intrahepatic lymphocytes (h) revealed a significant decrease in the distribution of CD4 T cells and an increase in CD8 subsets following fibrosis induction (plain bars, P < 0·001). A significant decrease in the number of natural killer (NK) cells was seen in the fibrotic group (P = 0·01). The findings are representative of four different experiments with the same number of eight animals in each subgroup.

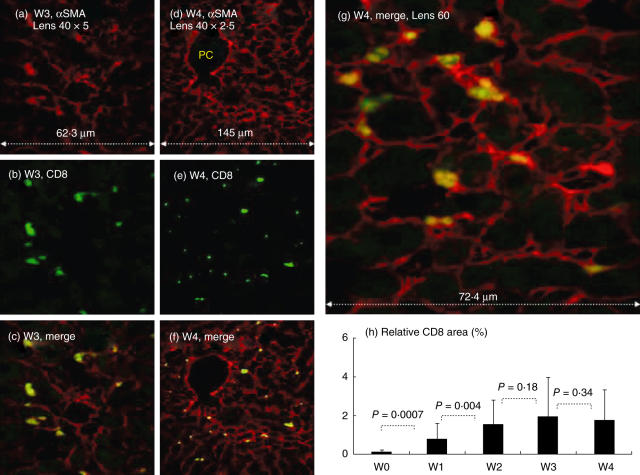

Fig. 3.

In situ CD8 staining. Direct CD8 hepatic stellate cell (HSC) adhesion in situ: confocal laser scanning microscopy was used as detailed in Fig. 3. At each time-point, Cy-5-conjugated αSMA and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD8 markers are illustrated with single (a,d: red laser; b,e: green laser, respectively) and merged stains (c,f,g: yellow–green cells). The larger merged panel is illustrated in (g). Following fibrosis induction, CD8 cells, stained as yellow, were found attached only to the HSC and mainly in the periportal spaces, and extend along the active side of fibrotic septa formations (c,f). (h) Increased relative area of CD8 following fibrosis induction, as described in Materials and methods. PC = portal space. The findings are representative of two different experiments with four animals in each time subgroup.

Fibrosis induction modulates hepatic lymphocyte subsets

Different subtypes of lymphocytes are thought to be involved in liver fibrosis as well as in the clearance of necrotic cells during inflammation [18–21]. Using FACS, intrahepatic lymphocyte subsets were analysed in both animal groups. Figure 2g,h shows liver lymphocyte alterations by FACS analysis and confirms our earlier results [11]. Following fibrosis induction, there was a significant (P = 0·02) increase of total intrahepatic lymphocytes from 1·57 ± 0·86 million cells to 3·73 ± 0·72. Although the total number of CD4, CD8 and NK subsets was increased following fibrosis induction (Fig. 2g), significant alterations of their distribution were demonstrated (Fig. 2h). Results showed a decreased component in intrahepatic CD4 T cells, from 29·76% ± 2·7 to a mean 14·07% ± 2·8 (P < 0·001). Liver CD8 T cells increased from 7·6% ± 0·9 in naive animals to 21·7% ± 2·4 in fibrotic animals (P < 0·001). Liver NK cells decreased from 10·8% ± 1·2 in naive animals to 9·6% ± 0·5 in fibrotic mice (P = 0·01).

After considering these confirmative FACS results, we assessed lymphocytes in situ on liver sections using confocal microscopy. Figures 3, 4 and 5 show representative stain samples from the third (a–c) and fourth weeks (d–g) of CCl4 induction. Panel (h) from the same figures show measured relative lymphocyte areas from each time-point of CCl4 induction.

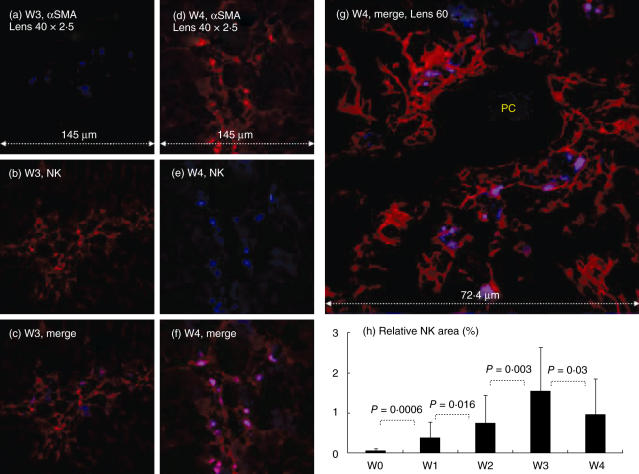

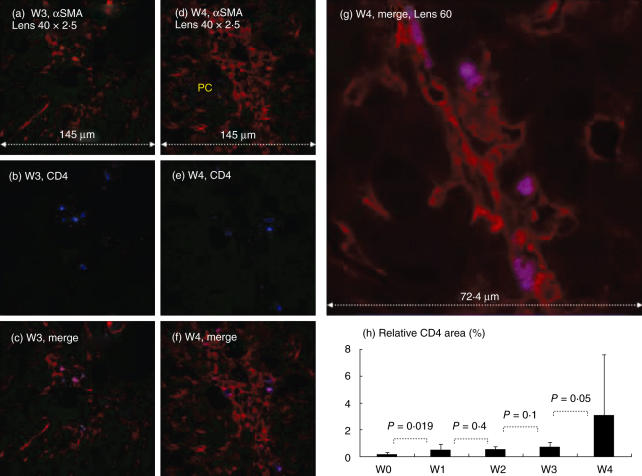

Fig. 4.

Direct natural killer (NK) hepatic stellate cell (HSC) adhesion in situ: confocal laser scanning microscopy was used as detailed in Fig. 2. Representative samples from the third (W3) and fourth (W4) weeks of CCl4 induction are shown in (a–c) and (d–g), respectively. Liver biopsies from fibrotic (a–g) but not naive animals (data not shown) showed positive-stained cells with primary antibodies to αSMA and NK in both single (a,d,b,e, respectively) and overlay images (c,f,g). The larger merged panel is illustrated in (g). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated NK cells, demonstrated in blue laser as single stain, were found attached only to the red HSCs and giving the purple colour, suggesting a direct NK/HSC attachment. NK cells are found mainly in the periportal spaces extending along the active side of fibrotic septa formations. PC = portal space. (h) Increased relative area of NK cells following fibrosis induction; as described in Materials and methods. The findings are representative of two different experiments with four animals in each time subgroup.

Fig. 5.

Direct CD4 hepatic stellate cell (HSC) adhesion in situ: confocal laser scanning microscopy was used as detailed in Fig. 4. At each time-point, Cy-5-conjugated αSMA and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD4 markers are illustrated with single (a,d: red laser; b,e: blue laser, respectively) and merged stains (c,f,g: purple cells). The larger merged panel is illustrated in (g). Similar to CD8 cells, CD4 subsets were found attached only to the HSCs and mainly in the periportal spaces and extend along the active side of fibrotic septa formations (c,f). (h) Increased relative area of CD4 subsets following fibrosis induction. PC = portal space. The findings are representative of two different experiments with four animals in each time subgroup.

Following fibrosis induction, NK cells were found very close to the HSC. At each time-point, Cy-5-conjugated αSMA in red and FITC-conjugated anti-pan-NK marker in blue laser are illustrated in single and merged stains. The overlay staining for both NK and αSMA markers in purple colour suggests the existence of a direct cell-to-cell attachment. NK/HSC proximity is located mainly in the periportal spaces and extends along the active side of the fibrotic septa formations (Fig. 4c,f,g). The NK/HSC overlay double-stained cells gradually increase at each sequential check-point. The measured relative NK area is 0·03% ± 0·09 in naive animals (Fig. 4h), then increases significantly to 0·4 ± 0·376 in the first week (P = 0·0006), 0·76 ± 0·68 in the second week (P = 0·016), 1·56 ± 0·07 in the third week (P = 0·0034) then decreases to 1·0 ± 0·88 in the fourth week (P = 0·03).

With increased αSMA/NK double-staining, CD8-stained cells followed a similar pattern (Fig. 3). At each time-point, Cy-5-conjugated αSMA and PE-conjugated anti-CD8 markers are illustrated with single (in red and green laser, respectively) and merged stains (yellow–green cells). They were detected initially mainly in the periportal area and thereafter were found to extend along the fibrotic septa formation (Fig. 3c,f,g). CD8 cells were always captured adjacent to the activated stellate cells, appearing early and abundantly during the first 2 weeks. The relative CD8 area was 0·01% ± 0·09 in naive animals (Fig. 3h), and then increased significantly, reaching a plateau within 2 weeks. The relative CD8 area was 0·8% ± 0·76 in the first week (P = 0·0007), 1·56% ± 1·3 in the second week (P = 0·0037) and 1·96% ± 2·07 and 1·75% ± 1·6 in the third and fourth weeks, respectively (P = 0·18 and P = 0·34, respectively).

To a lesser extent, and along with the FACS results showing decreased CD4 distribution, CD4 T cells first appeared in situ at week 2 (Fig. 5). At each time-point Cy-5-conjugated αSMA (Fig. 5a,d) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 markers (Fig. 5b,e) are illustrated with single (in red and blue laser, respectively) and merged stains (Fig. 5c,g, purple cells). They were much less abundant than CD8 and NK cells. Furthermore, CD4 cells were also seen mainly at the periportal spaces and then along the fibrosis septa. Like CD8 cells, the CD4 subsets were found attached mainly to activatedαSMA-positive HSC (Fig. 5c,f,g). The relative CD4 area was 0·13% ± 0·1 in naive animals (Fig. 5h), then increased significantly thereafter to 0·41 ± 0·41 in the first week (P = 0·019). No marked increase in CD4 staining was seen throughout the first 3 weeks of CCl4 induction (0·44 ± 0·24 and 0·62 ± 0·4 in the second and third weeks, respectively (P = 0·43 and P = 0·1). The CD4 numbers significantly increased to 2·8 ± 4·3 in the fourth week (P = 0·056).

All liver sections from naive animals showed no positive staining to lymphocyte subsets (data not shown, as they were similar to Fig. 1d), suggesting that stained lymphocytes following CCl4 induction are activated with a special affinity to adhere to liver tissue. The increased number of isolated total intrahepatic lymphocytes from all subsets also explains the increased appearance of stained lymphocytes. The distributional pattern of lymphocyte subsets by FACS analysis is similar to that seen in stained lymphocytes.

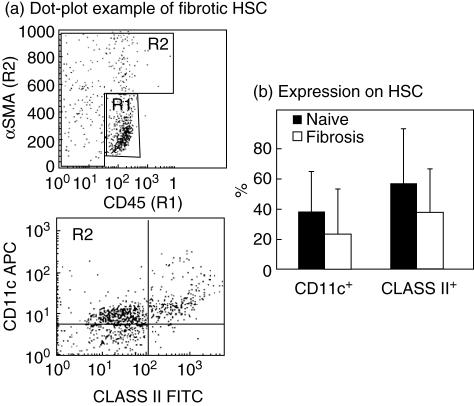

CD11c and class II expression by mouse HSC

Based on these observations of direct interactions between HSC and lymphocytes, earlier suggestions that HSC might have an antigen presentation capability were strengthened further [22]. Following fresh HSC isolation from naive and fibrotic mouse livers, FACS analysis was performed using antibodies for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and CD11c molecules. While anti-αSMA antibodies were used to allocate and purify the HSC population (gated as R2), anti-CD45 antibodies (gated as R1) were used to exclude contaminated lymphocytes further, achieving optimal purification for CD11c and class II analysis (Fig. 6a). Average HSC expression of class II molecules was evident, and did not change significantly following fibrosis induction; 55% ± 35 in the naive control animals compared with 37% ± 28 in the fibrotic group with non-significant P-values (Fig. 6b). HSC expression of CD11c was also seen, but without a significant change following fibrosis; 36% ± 26 in the naive control group compared with 22% ± 29 in the fibrotic group. The MHC class II and CD11c expressions on the HSC surface support the previous observation that HSC has an antigen presentation capability.

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of hepatic stellate cells (HSC): fresh HSCs isolated from naive and fibrotic livers were analysed by FACS using antibodies for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and CD11c molecules, purified HSC were allocated using anti-αSMA antibodies (gated as R2) and contaminated CD45-stained lymphocytes (gated R1) were excluded (see dot plot example, a), all as described in Materials and methods. An average HSC expression of class II molecules was evident and did not change following fibrosis (b): 55% ± 35 in the naive control group and 37% ± 28 in the fibrotic group, with non-significant P-values. HSC expression of CD11c was also seen, without a significant change following fibrosis: 36% ± 26 in the naive control group and 22% ± 29 in the fibrotic group.

Discussion

In this study we show that the role of lymphocytes in fibrosis induction seems to be modulated through direct attachment with HSC. This role is emphasized by cell-to-cell proximity and surface contact. Hepatic fibrosis was induced by CCl4, as confirmed by conventional analysis of Sirius red liver staining (Fig. 1a,b) and αSMA Western blotting (Fig. 1c). Post-fibrosis, direct contacts between the studied lymphocyte subsets and HSC were manifest. We suggest that as a result of the liver insult, lymphocytes migrate into the space of Disse and interact with activated HSC. This supports our previous functional results [11,12]. NK cells attach markedly to the activated HSC and increase throughout CCl4 administration. Supporting our finding, it was reported that initially, after toxin administration, the tissue concentration of IFN-γ [23] increases, which is followed by an increase in concentration of TNF-α [24], both of which are released by NK cells as well as by Küpffer cells. Both these cytokines alter the expression of the cell adhesion molecules on the sinusoidal endothelial cells [25], allowing the recruitment and sinusoidal transmigration of inflammatory cells, which precedes the death of hepatocytes. Both FACS analysis and confocal imaging reveal an early appearance and a significant increase of intrahepatic CD8 subsets carrying profibrogenic properties. In parallel with decreased liver CD4 FACS counts, confocal studies of the liver sections showed a late appearance and less cell-to-cell attachment of CD4 T cells to HSC, compared to CD8 cells. These results suggest that all lymphocyte subsets infiltrate the subendothelial space and probably interact directly with activated HSC by adhesion. Activated HSC, on their part, arise from the portal spaces and extend along fibrotic septa [26], which explains our finding that all studied subsets initially began to appear mainly at the periportal space and then extend along the active fibrosis septa.

Liver inflammation in many animal models as well as in humans is initiated by the death of hepatic resident cells and the recruitment of extrahepatic inflammatory cells [17–20]. Leucocytes gain access to the liver tissue through the portal tracts, sinusoids or the central vein. However, the distribution of the hepatic infiltration depends on the predominant pathohistological localization of the damage [27]. The inflammatory infiltrate may include T lymphocytes, which tend to have a more peripheral distribution, B lymphocytes, which mainly have a central distribution, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, NK cells and mast cells [26]. As the result of the hepatic insult, there is also recruitment of perisinusoidal HSC and interstitial fibroblasts, both of which play a substantial role in septal formation [28].

We have reported previously that CD8+ T cells are involved in mediating fibrosis [11], while NK cells provide an anti-fibrotic role [12].

Human HSCs were proposed previously to have features of an antigen-presenting cell (APC), and to stimulate lymphocyte proliferation [22]. Cultured human HSCs express membrane proteins involved in antigen presentation, including members of the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) family (HLA-I and HLA-II), lipid-presenting molecules (CD1b and CD1c) and factors involved in T cell activation (CD40 and CD80). Furthermore, cells isolated freshly from human cirrhotic livers (in vivo-activated HSCs) express highly HLA-II and CD40, suggesting that HSCs can act as APCs in human fibrogenesis [22]. The high expression of CD11c and HLA class II molecules expressed by freshly isolated HSC in our mouse fibrosis model supports the APC capacity of HSC. Moreover, the direct HSC/lymphocyte adhesion seen by confocal microscopy strengthens this hypothesis further.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that HSC is attached directly to lymphocytes following fibrosis induction, which is in good agreement with earlier FACS results. The fact that HSC attaches directly to lymphocytes, together with the increased expression of MHC class II and CD11c, suggests that HSCs have features of an APC.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Mark Tarshish is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by grants from ‘Return to Hadassah’, ‘Compensatory’, ‘Horovetz’ and Bi National American Israeli Scientific Foundation (BSF) Awards (grant nos 8033601, 8033603, 8033604 and 8033605).

References

- 1.Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2247–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis − from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl. 1):S38–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, et al. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:955–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K, Dooley S. Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d793–807. doi: 10.2741/A812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SC, Ohata M, Schrum L, Rippe RA, Tsukamoto H. Expression of interleukin-10 by in vitro and in vivo activated hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:302–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson K, Maltby J, Fallowfield J, McAulay M, Millward-Sadler H, Sheron N. Interleukin-10 expression and function in experimental murine liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology. 1998;28:1597–606. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Z, Wakil AE, Rockey DC. Strain-specific differences in mouse hepatic wound healing are mediated by divergent T helper cytokine responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Zheng S, Dalton DK, Locksley RM. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon gamma-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1367–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guler ML, Gorham JD, Hsieh CS, et al. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in TH1 cell development. Science. 1996;271:984–7. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzel FP, Sadick MD, Holaday BJ, Coffman RL, Locksley RM. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safadi R, Ohta M, Alvarez CE, et al. Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 lymphocytes and its attenuation by transgenic interleukin 10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:870–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melhem A, Muhanna N, Bishara A, et al. Anti-fibrotic activity of NK cells in experimental liver injury through killing of activated HSC. J Hepatol. 45:60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman SL, Rockey DC, McGuire RF, Maher JJ, Boyles JK, Yamasaki G. Isolated hepatic lipocytes and Kupffer cells from normal human liver: morphological and functional characteristics in primary culture. Hepatology. 1992;15:234–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greets A, Eliasson C, Niki T, Wielant F, Pekny M. Formation of normal desmin intermediate filaments in mouse hepatic stellate cells requires vimentin. Hepatology. 2001;33:177–88. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sham RL, Packman CH, Abboud CN, Lichtman MA. Signal transduction and the regulation of actin conformation during myeloid maturation: studies in HL60 cells. Blood. 1991;77:363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brelje TC, Wessendorf MW, Sorenson RL. Molecular laser scanning focal microscopy. practical application and limitations. Meth Cell Biol. 2002;70:165–244. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(02)70006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JI, Lee KS, Paik YH, et al. Apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells in carbon tetrachloride induced acute liver injury of the rat: analysis of isolated hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2003;39:960–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inada S, Suzuki K, Kimura T, et al. Concentric fibrosis and cellular infiltration around bile ducts induced by graft-versus-host reaction in mice. a role of CD8+ cells. Autoimmunity. 1995;22:163–71. doi: 10.3109/08916939508995313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laso FJ, Iglesias-Osma C, Ciudad J, Lopez A, Pastor I, Orfao A. Chronic alcoholism is associated with an imbalanced production of Th-1/Th-2 cytokines by peripheral blood T cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laso FJ, Iglesias-Osma C, Ciudad J, et al. Alcoholic liver cirrhosis is associated with a decreased expression of the CD28 costimulatory molecule, a lower ability of T cells to bind exogenous IL-2, and increased soluble CD8 levels. Cytometry. 2000;42:290–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombardo L, Capaldi A, Poccardi G, Vineis P. Peripheral blood CD3 and CD4 T-lymphocyte reduction correlates with severity of liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Laboratory Res. 1995;25:153–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02592558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinas O, Bataller R, Sancho-Bru P, et al. Human hepatic stellate cells show features of antigen-presenting cells and stimulate lymphocyte proliferation. Hepatology. 2003;38:919–29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batusic DS, Armbrust T, Saile B, Ramadori G. Induction of Mx-2 in rat liver by toxic injury. J Hepatol. 2004;40:446–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knittel T, Mehde M, Kobold D, Saile B, Dinter C, Ramadori G. Expression patterns of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells of rat liver (regulation by TNF-alpha and TGF-beta1) J Hepatol. 1999;30:48–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neubauer K, Ritzel A, Saile B, Ramadori G. Decrease of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1-gene-expression in inflammatory cells and in endothelial cells in the rat liver following CCl(4)-administration and in vitro after treatment with TNF-alpha. Immunol Lett. 2000;74:153–64. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Weidner IC, et al. Comparative quantitative analysis of macrophage populations defined by CD68 and carbohydrate antigens in normal and pathologically altered human liver tissue. Anal Cell Pathol. 1998;16:141–50. doi: 10.1155/1998/192975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmi M, Adams D, Jalkanen S. Cell adhesion and migration. IV. Lymphocyte trafficking in the intestine and liver. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G1–G6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhunchet E, Wake K. Role of mesenchymal cell populations in porcine serum-induced rat liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 1992;16:1452–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]