Abstract

Deletion complexes consisting of multiple chromosomal deletions induced at single loci can provide a means for functional analysis of regions spanning several centimorgans in model genetic systems. A strategy to identify and map deletions at any cloned locus in the mouse is described here. First, a highly polymorphic, germ-line competent F1(129/Sv-+Tyr+p × CAST/Ei) mouse embryonic stem cell line was established. Then, x-ray and UV-induced mutagenesis was performed to determine the feasibility of generating deletion complexes throughout the mouse genome. Reported here are the selection protocols, induced mutation frequencies, cytogenetic and extensive molecular analysis of mutations at the X-chromosome-linked hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) locus and at the neural cell adhesion molecule (Ncam) locus located on chromosome 9. Mutation analysis with PCR-based polymorphic microsatellite markers revealed deletions of <3 cM at the Hprt locus, whereas results consistent with deletions covering >28 cM were observed at the Ncam locus. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with a chromosome 9 paint revealed that some of the Ncam deletions were accompanied by complex chromosome rearrangements. In addition, deletion mapping in combination with loss of heterozygosity of microsatellite markers revealed a putative haploinsufficient region distal to Ncam. These data indicate that it is feasible to generate x-ray-induced deletion complexes in mouse embryonic stem cells.

Radiation mutagenesis has provided genetic resources in the mouse for over 60 years, yielding chromosomal deletions, translocations, inversions, and duplications, as well as intragenic mutations. The most productive screen for radiation-induced mutations, the specific-locus test, was initiated by W. L. Russell (1). Based on previous experiments in Drosophila melanogaster, the specific-locus test was a screen for recessive mutations in progeny of wild-type mutagenized mice at seven specific loci: agouti (a), brown (now known as tyrosinase-related protein or Tyrp1), albino (now known as tyrosinase or Tyr), dilute (now known as myosinVa or Myo5a), short ear (now known as bone morphogenetic protein 5 or Bmp5), pink-eyed dilution (p), and piebald (now known as endothelin receptor type B or Ednrb). Mutations at any one of these seven loci were identified by crossing mutagenized mice to a tester stock homozygous for visible, recessive mutations at the seven loci. Subsequently, Lyon and Morris (3) generated mutation rates for an additional set of specific loci: agouti (a), brachypody (now known as growth differentiation factor 5 or Gdf5), fuzzy (fz), leaden (ln), pallid (pa), and pearl (pe).

Although initially designed to estimate the genetic hazards of radiation exposure on humans, the induced mutations from the specific-locus test have provided a wealth of biological information on regions flanking specific loci (reviewed by ref. 4). For instance, complementation and phenotypic analysis of deletions at the Tyr locus led to a functional map of a 6- to 11-cM region of mouse chromosome 7 (2, 5, 6). This functional map includes six regions defined by deletion breakpoints required at various stages of development. In addition, a mutagenesis screen to identify mutable genes in the region covered by the deletions (7–9) has been performed with the point mutagen, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) (10). This screen, based on noncomplementation with the albino deletions, identified and mapped Tyr-linked, recessive lethal, ENU-induced mutations to known and previously unidentified essential loci in the albino region.

Saturation mutagenesis of the region of chromosome 7 covered by the deletions is a model for systematic mutagenesis of the entire mouse genome. However, although deletion complexes have been generated at the specific loci as well as a limited number of other loci, including Brachyury (T), mast cell growth factor (Mgf), and the kit oncogene (kit), the fraction of the genome included in deletion complexes is only 3% (4). Deletions have been isolated in other regions and can be detected efficiently (3, 11), but the ability to generate multiple germ-line-induced deletions at a given locus is limited even at large mouse facilities because of the number of progeny that must be screened (12). Thus, factors that contributed to successful mutagenesis at the Tyr locus, a visible phenotypic marker and the ability to screen large populations to isolate a deletion complex, are limiting for saturation mutagenesis at other loci in the mouse genome.

Mutagenesis in the mouse can be performed in vitro by using mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and offers an alternative mutation resource that could circumvent the limiting factors for generating deletion complexes in mice. The most common form of mutagenesis in ES cells is targeted mutagenesis via homologous recombination, which is an efficient method for introducing a specific intragenic mutation in a predetermined locus (13–16). In vitro mutagenesis, however, is not limited to targeted mutations and offers an accessible method for generating a variety of mutations, including radiation-induced deletions. In other cell types, radiation-induced deletions have been mapped beyond the target gene by using linked markers at the endogenous hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) (17), thymidine kinase (Tk) (18), and adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (Aprt) loci (19).

Deletion mapping at autosomal loci is dependent on linked polymorphic markers. A basic strategy to identify and map deletions that could be used at any cloned locus in the mouse genome is to target a selectable marker into a predetermined locus in an ES cell line polymorphic for a large portion of the >6,000 PCR-based microsatellite markers available in the mouse genome (20). Deletions therefore could be induced, selected, and mapped by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the PCR-based polymorphic microsatellite markers, and because the deletions are in ES cells, the potential exists to generate mice from the deletion cell lines.

Two criteria for this strategy to work are the creation of a highly polymorphic ES cell line as well as optimizing the efficiency of isolating, detecting, and inducing deletions in ES cells, and these two points are the focus of the work reported here. Various protocols were tested for inducing mutations at the X-linked Hprt locus and at a herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) gene targeted to mouse chromosome 9 in the neural cell adhesion molecule (Ncam). The mutagenesis was performed in a highly polymorphic, male, germ-line-competent F1(129/Sv-+Tyr + p × CAST/Ei) ES cell line. Reported are the optimized selection protocols, induced mutation frequencies, and extensive molecular analysis of mutations at the Hprt and Ncam loci. In addition, fluorescence in situ hybridization with a chromosome 9 paint revealed that cytogenetic analyses are critical for selecting interstitial deletions without associated complex chromosomal rearrangements. Although we have not yet determined whether these mutated genomes would survive in the germ line, the results of this work significantly extend the molecular characterization of radiation-induced mutations in ES cells and support the finding of You et al. (21) that radiation-induced deletion complexes can be efficiently generated in ES cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

F1 ES Cell Line.

129/Sv +Tyr +p females and CAST/Ei males were mated to produce an F1(129/Sv +Tyr +p × CAST/Ei) male, germ-line-competent ES cell line, CAST no. 1. ES cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in MEM alpha medium, supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1,000 units/ml of leukemia inhibitory factor (22), and maintained on primary feeder cells or gelatin-coated plates. Medium was supplemented with G418 (250 μg/ml), 10−5 M 6-thioguanine, and gancyclovir (GANC) (2.5–10 μM) (Syntex Laboratories) or FIAU, 1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil (called fialuridine) (0.2 μM) (gift from Bruce Lamb, Case Western Reserve University), for selection of neomycin (neo+), HPRT−, and HSV-tk− cells, respectively.

Ncam Targeting.

A 7.4-kb KpnI genomic fragment containing Ncam exons 16–18 (23) was used to make two replacement targeting constructs, ΔB7.4TK/BAN and ΔB7.4TK/NpA−/BADT. Both included a BamHI fragment containing HSV-tk and β-actin-neo (21, 23) or HSV-tk with pgk-neo (23) lacking a polyadenylation signal integrated in the 7.4-kb KpnI genomic fragment at a BamHI site. A diphtheria toxin A-chain gene, BADT (24), was added outside the region of homology to enrich for targeted events in ΔB7.4TK/NpA−/BADT.

Electroporation, selection, and detection of targeted clones was performed as described elsewhere (23, 25). Two Ncam-specific probes, a partial Ncam cDNA containing exons 16, 17 and part of exon 19 (23) and a genomic clone including exon 14 (26), were used to detect polymorphisms indicative of homologous integration for identification of targeted clones. Three targeted lines were isolated at a frequency of 1/59 and were determined to have targeted the 129/Sv +Tyr +p allele based on a strain-specific restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Mutagenesis.

The basic protocol for ES cell mutagenesis was as follows. Cells were split in nonselective media on gelatin-coated dishes 2 days before treatment. The day of treatment, cells were trypsinized, counted, and plated in nonselective medium on 100-mm gelatin-coated dishes. Cells were refed nonselective medium the day after treatment and then every other day until selection was initiated. The day after initiating selection the cells were refed selective medium and then every other day for at least 4 days. At this time, approximately 1 week after the cells were plated for selection, the surviving colonies were counted, picked, and expanded for analysis. Cells (2 × 103) were treated in parallel with each experimental population and maintained in nonselective medium to estimate plating efficiency and cell survival (average plating efficiency, 20%).

For mutagenesis at Hprt, cells were plated at a density of 1–2 × 106 cells/dish for the untreated spontaneous controls and 3–5 × 106 cells/dish for UV or x-ray exposed samples. A 5- to 6-day expression time is necessary for clearance of residual Hprt message and protein (13) and necessitated the passage of the cells one or two times. The final passage for selection was performed 2 days before initiating 6-thioguanine (6-TG) selection at a uniform density of 5 × 105 cells/100-mm dish (1 × 105 cells accounting for plating efficiency) to maximize the number of cells assayed and minimize variation in 6-TGr mutant recovery based on cell density.

For mutagenesis at Ncam/tk, targeted cell lines were maintained in G418 medium and split to gelatin-coated dishes in nonselective medium 2 days before treatment. Five of six protocols tested with GANC had at least a 4-day expression time and resulted in clear induction of GANCr colonies after x-ray treatment at permissive cell densities. In the favored protocol, cells were plated for treatment as for the Hprt locus, split 3 days later at a density of 2.5 × 105/100-mm dish (5 × 104 cells accounting for plating efficiency) and selection with 2.5 μM GANC initiated the next day, 4 days after treatment. Three protocols using FIAU selection with a 2- to 4-day expression time had clear induction of FIAUr colonies after x-ray treatment. In the protocol favored for isolating FIAUr colonies, cells were plated at 2 or 3–5 × 105 cells/100-mm dish for spontaneous and 2 or 3 × 106 cells/100-mm dish for x-ray treatment, refed the next day in nonselective media, and selection initiated with FIAU 2 or 3 days after exposure. Cell density for experiments initiating selection 2 days after treatment was 0.6–1 × 105 cells/100-mm dish and 0.4–0.5 × 105 cells/100-mm dish for a 3-day expression time.

Cells were exposed to 4 Gy of x-rays by using a Siemens’ Stabilipan x-ray generator (250 kVp, 15 mA, HVL 1.5 mm Cu) at a rate of 90 Rad/min in media on 100-mm dishes and resulted in an average 88% cell death. This dose of x-rays, based on the survival fraction, was expected to induce mutations above background (27). Cells were exposed to 4.2 J of UV light from a 30W Sylvania germicidal lamp (253.7 nm). Exposure to this dose of UV light resulted in an average 84% cell death.

Mutation Analysis.

Colonies were expanded to either 35- or 60-mm dishes for DNA isolation. Primer pairs were selected based on map position and polymorphism information from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology genome center and purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). Approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA was used in a 20-μl hot start reaction with 35 cycles of 95°C, 30”; 58°C, 30”; 72°C, 30”, with a final 7-min extension at 72°C. All reactions were performed in a standard buffer consisting of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.3), and 50 mM KCl. Controls for X chromosome primers included a positive genomic DNA sample and blank, whereas controls for the chromosome 9 primers were an F1(129/Sv +Tyr +p × CAST/Ei), 129/Sv-+Tyr +p, CAST/Ei, and blank DNA sample. To reduce incorrect scoring of loss of X-linked markers, three reactions were run in parallel with three sets of primers by using DNA aliquoted from a common reaction mix. In addition, secondary amplification signals often were associated with these reaction conditions and provided an internal control. Each reaction was electrophoresed on a 15-cm vertical (R. Schadel, San Franciso, CA), 8% polyacrylamide gel, stained with ethidum bromide, photographed, and scored. Reactions from the same primer pair, including the controls, always were run together for comparison.

A mouse chromsome 9 paint (Oncor) was hybridized to metaphase spreads and detected according to the manufacturer. Images were captured with a charge-coupled device camera and processed with Adobe Photoshop and Biological Detection System (BDS) Registration.

Mutation Frequency and Independent Mutation Estimate.

Mutation frequencies were calculated from the number of colonies surviving selection and the total number of cells assayed, taking into account plating efficiency and cell survival after treatment. Independent mutation estimates were based on the following criteria. For experiments involving a cell split between exposure and selection, all mutations were considered duplicates until otherwise shown to be different by molecular analysis, whereas clones isolated in experiments without a cell split were assumed to be independent mutations with the exception of no or complete LOH of the PCR-based polymorphic 129/Sv-+Tyr +p markers. Parallel spontaneous mutations were compared with the treated population and any mutation that was present in the exposed and spontaneous mutants was assumed to be a pre-existing mutation and only counted as one independent spontaneous mutation.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis and Mutations at an X-Linked Hemizygous Locus.

A number of endogenous as well as introduced bacterial viral genes have been used in various in vitro mutagenesis screens (27–31). Of these loci, the Hprt locus has been most commonly used as a target because both forward and reverse selection are possible. Furthermore, Hprt is located on the X chromosome, thereby providing for easy selection schemes in male cell lines hemizygous for the locus (32, 33). As a result, mutation spectra and frequencies for intragenic and multilocus mutations induced by treatments such as x-rays, UV, or no treatment have been extensively characterized at the Hprt locus in a number of cell lines derived from Chinese hamster, mouse, and human (17, 34–43). To gain some comparison between these cells, our experiments in ES cells began with the Hprt locus.

Three ES cell lines were used for mutagenesis at the Hprt locus, CAST no.1 and Ncam targeted subclones Ncam/tk D8 and Ncam/tk F8. The spontaneous 6-TGr frequency was <1/106 in all three cell lines, whereas the x-ray-and UV-treated 6-TGr frequencies ranged from 5–25/106 and 20–39/106, respectively (Table 1). Spontaneous (n = 3), x-ray-exposed (n = 45), or UV-exposed (n = 66) 6-TGr clones were analyzed with Hprt-linked markers, DXMit22, DXMit23 and DXMit159. DXMit22 and DXMit23 are less than 10 kb 5′ and 3′ of the Hprt gene, respectively, whereas DXMit159 is a closely linked 3′ (distal) marker. Based on the presence of all three linked markers, one spontaneous, 24 x-ray-exposed, and 60 UV-exposed 6-TGr clones were classified as intragenic mutations, whereas loss of at least one linked marker, indicative of a deletion, was observed in two spontaneous, 21 x-ray-exposed, and six UV-exposed 6-TGr clones.

Table 1.

Mutation frequencies at the Hprt and Ncam/tk

| Cell line | Number of 6-TGr(Hprt−) or FIAUr/GANCr(Ncam/tk−) cells/total cells

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous

|

X-ray

|

UV

|

|||||

| 6-TG | FIAU | GANC | 6-TG | FIAU | GANC | 6-TG | |

| CAST #1 | 2/4.5 × 106 | No data | No data | 29/2.4 × 106 | No data | No data | 80/4 × 106 |

| Ncam/tk F8 | 0/2 × 106 | 16/8.8 × 105 | 20/2.7 × 106 | 45/1.8 × 106 | 130/8.9 × 105 | 63/2.4 × 106 | 43/1.8 × 106 |

| Ncam/tk D8 | 1/1.1 × 106 | 0/1.4 × 105 | 9/5.6 × 105 | 8/1.5 × 106 | 1/1.1 × 105 | 15/7.6 × 105 | 24/6.1 × 105 |

| Ncam/tk G12 | No data | 49/8.6 × 105 | No data | No data | 64/7.2 × 105 | No data | No data |

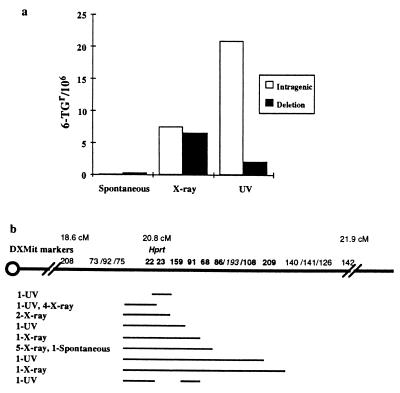

The frequency of intragenic and deletion mutations is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Intragenic mutations were observed at frequencies of 0.14/106, 7.5/106, and 22/106, whereas deletions were recovered at a frequency of 0.26/106, 6.5/106, and 2/106 in the spontaneous-, x-ray- and UV-treated populations, respectively. Mutations showing loss of at least one marker were tested with 12 additional markers mapping within a centimorgan of Hprt and DXMit208 and DXMit142, which map approximately 2 cM proximal and 1 cM distal to Hprt. On the basis of these results, 19 independent deletion mutations were identified and categorized into nine groups based on presence or absence of markers (Fig. 1b). All deletions mapped within 1 cM distal and proximal to Hprt with no obvious correlation between mutagen and deletion size. In addition, the PCR-based analysis was consistent with Southern data for 73 of 74 of the 6-TGr clones analyzed with an Hprt exon 7–9 specific probe (data not shown). The one exception was a UV-exposed clone, which, based on Southern analysis, lost the 3′ end of Hprt but by PCR was typed as a skipping deletion that did not include the 3′ linked DXMit23 and DXMit159 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Mutation spectrum and map of deletions at Hprt. (a) Calculation of the number of intragenic or deletion mutations in the spontaneous, x-ray, and UV exposed populations was performed by dividing the total 6-TGr frequencies into two frequencies based on the proportion of each mutation type in each population. The type of mutation was determined by the presence or absence of DXMit22, DXMit23, and DXMit159. (b) Breakpoint map of deletions based on presence or absence of DXMit makers listed above the chromosome. The maximum size of each deletion group is represented by a line with the number and origin of independent mutations in each group indicated on the left. Bold type indicates unambiguous physical placement, italics indicate the most likely placement, and roman type indicates that the linked markers could not be ordered based on the deletion data. The genetic location is indicated above the microsatellite markers. The diagram is not to scale.

Mutagenesis and Mutations at a Diploid Autosomal Locus.

Definitive molecular analysis is more difficult for multilocus mutations at diploid autosomal versus hemizygous loci unless significant heterozygosity exists in the target cell line. To circumvent this problem, experiments were designed to integrate a negative selectable vector containing HSV-tk into the Ncam locus in our highly polymorphic CAST no. 1 ES line. Ncam was chosen as the anchor locus because it is a nonessential (23) autosomal locus, thereby offering the potential for mapping multilocus mutations based on a large set of linked polymorphic microsatellite markers (20, 44). Furthermore, deletions could be generated, which in combination with the more distal chromosome 9 dilute/short ears deletions (1), would cover two-thirds of mouse chromosome 9.

In three clonal F1 cell lines with an integrated HSV-tk at the Ncam locus, the FIAU frequency of spontaneous and x-ray-treated populations varied from 0–57/106 and 9–146/106, respectively, whereas the corresponding GANCr frequencies varied from 7–16/106 and 20–26/106 (Table 1). Although the spontaneous mutation frequency at Ncam/tk was comparatively higher than the Hprt locus, about a 3-fold increase in FIAUr and GANCr was observed after x-ray exposure (Table 1). These data, together with a subsequent series of experiments (data not shown), revealed that in most cases a higher recovery of HSV-tk− cells was achieved with FIAU versus GANC.

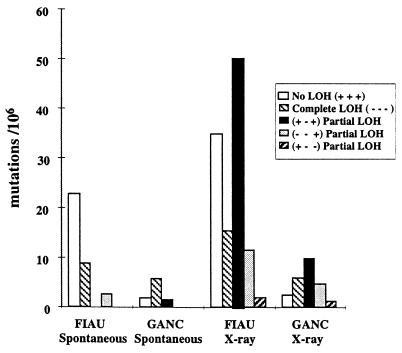

Spontaneous (no exposure) (n = 27 FIAUr, n = 25 GANCr) and x-ray-exposed clones (n = 59 FIAUr, n = 61 GANCr) were tested with chromosome 9 markers D9Mit64, D9Mit22, and D9Mit196 for LOH of the 129/Sv +Tyr +p versus CAST/Ei specific alleles. D9Mit64 is located 18 cM proximal to Ncam, D9Mit22 is in the genomic portion of the Ncam targeting construct, and D9Mit196 is 19 cM distal to Ncam. Based on the presence or absence of these three 129/Sv +Tyr +p specific alleles and subsequent marker analysis, the FIAUr and GANCr clones were placed into one of five mutation classes. The majority of spontaneous Ncam/tk mutations had either no (+ + +) LOH (n = 18 FIAUr and n = 5 GANCr) or complete (− − −) LOH (n = 7 FIAUr and n = 16 GANCr) with a few (n = 4 GANCr and n = 2 FIAUr) partial (+ − +) or (− − +) LOH mutations. x-ray-exposed mutations were predominantly partial LOH mutations; for (+ − +) n = 26 FIAUr and n = 25 GANCr, for (− − +) n = 6 FIAUr and n = 12 GANCr and for (+ − −) n = 1 FIAUr and n = 3 GANCr, but also included a significant fraction of no (+ + +) LOH (n = 18 FIAUr and n = 6 GANCr) and complete (− − −) LOH (n = 8 FIAUr and n = 15 GANCr) mutations.

The frequency of each type of mutation is illustrated in Fig. 2. No and complete LOH mutations were induced no more than 1.8-fold after x-ray exposure, whereas a dramatic increase in the partial LOH mutations was evident in the x-ray-exposed clones. In particular, the (+ − +) partial LOH class was observed at a frequency of ≈1/106 in the spontaneous GANC/FIAU selected populations in contrast to 10–50/106 in the x-ray-exposed GANC/FIAU selected populations. The spectra of mutations was similar in both the FIAUr and GANCr clones with one exception, the majority of spontaneous FIAUr mutations had no LOH, whereas the majority of spontaneous GANCr mutations had complete LOH. This finding could be the result of selection differences; however, it should be noted that the majority of FIAUr and GANCr clones were not from the same clonal targeted cell line. Therefore, this result may reflect cell line-based differences.

Figure 2.

Mutation spectrum at Ncam/tk in the FIAUr and GANCr clones. Calculation of the number of each mutation type in the spontaneous and x-ray exposed populations was performed by dividing the total FIAUr or GANCr frequencies into five frequencies based on the proportion of each mutation type [no LOH (+ + +), complete LOH (− − −), and partial LOH (+ − +), (− − +) or (+ − −)] in each population. The mutation type was based on the loss of heterozygosity of microsatellite markers, D9Mit64, D9Mit22, and D9Mit196.

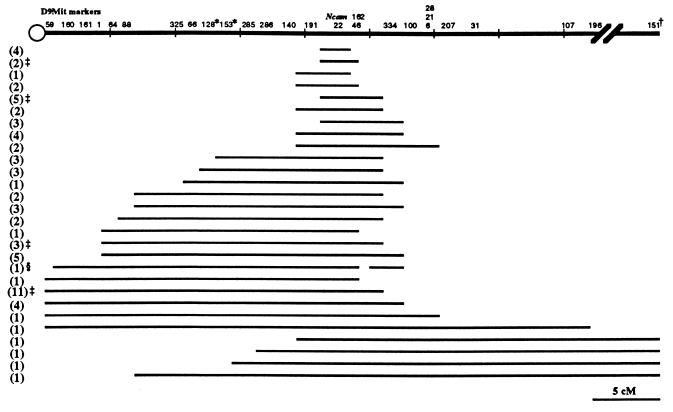

Seventy-nine partial LOH clones were analyzed with 7–14 additional chromosome 9 markers necessary to define extent of LOH. Seventy-two independent partial LOH mutations were identified and categorized into 28 groups shown in Fig. 3. (+ − +) partial LOH mutations (n = 50) covered a 28 cM region from D9Mit160, 21 cM proximal to Ncam, to D9Mit28, 7 cM distal to Ncam. (− − +) partial LOH mutations (n = 18) extended from the most proximal marker D9Mit59 tested to D9Mit196, 19 cM distal to Ncam, covering 42 cM. (+ − −) partial LOH mutations (n = 4) included the entire chromosome 9 distal to D9Mit64, 5 cM from the centromere and 18 cM proximal to Ncam.

Figure 3.

Map of loss of heterozygosity in the Ncam/tk mutations. The maximum loss of heterozygosity is indicated by a line for each mutation group and the number of independent mutations in each group is indicated on the left. D9Mit22 is in the Ncam locus. ∗ indicates an inconsistency in the order of the markers as defined by the deletions and the genetic position, the order based on the deletions is shown. † indicates map position 59.9 cM. ‡ indicates that one of the mutations in that group was of spontaneous origin. § Indicates the presence of the 129/Sv-+Tyr +p allele and absence of the CAST/Ei allele.

Cytogenetic and Dosage Analysis of Ncam/tk Mutations.

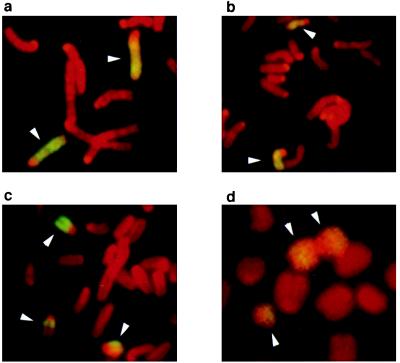

The pattern of LOH most prevalent in the x-ray-induced mutations was consistent with interstitial deletions. To classify the mutations further, fluorescence in situ hybridization with a chromosome 9 paint was performed on the Ncam/tk F8 line, four (+ − +) partial LOH clones, and the most extensive (− − +) partial LOH clone. Two of the (+ − +) partial LOH clones with LOH between 1 to 2 cM or 1 to 5 cM had two intact chromosome 9 signals like the parental line (Fig. 4a and data not shown), although one clone with 11–14 cM LOH had one noticeably smaller chromosome 9 (Fig. 4b, arrow, top center). The other (+ − +) partial LOH clone with 2–3 cM of LOH appeared to have an intact chromosome 9 (Fig. 4c, arrow, upper left), a smaller chromosome 9 (Fig. 4c, arrow, lower right) and a third smaller translocation signal associated with another chromosome (Fig. 4c, arrow, lower left). The (− − +) partial LOH clone with at least 35 cM of LOH had two chromsome 9 signals in an apparent isochromosome (Fig. 4d, top two arrows) and a third smaller chromosome 9 signal (Fig. 4d, arrow, bottom left). These results are consistent with four of the partial LOH clones being interstitial deletions, the largest associated with a duplication of the CAST/Ei chromosome 9, whereas one partial LOH clone was consistent with a more complex rearrangement, possibly a translocation-associated deletion.

Figure 4.

Cytogenetic analysis of Ncam/tk mutations. A chromosome 9 paint was hybridized to metaphase spreads from (a) a mutation clone with 1–5 cM LOH showing no detectable difference in size between the labeled chromosomes, (b) 11–14 cM LOH showing a detectably smaller chromosome (arrow, center top), (c) 2–3 cM LOH showing an intact chromosome 9 (arrow upper left), a smaller chromosome 9 (arrow lower right), and a third smaller translocation signal associated with another chromosome (arrow lower left). (d) >35 cM LOH showing two chromsome 9 signals in an apparent isochromosome (top center two arrows) and a third smaller chromosome 9 signal (arrow bottom left). The chromosome 9-specific signals are yellow, whereas the rest of the chromosomes were detected by propidium iodine and are red. Arrows indicate the chromsome 9-specific signal.

The fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis along with the pattern of LOH in the (+ − +) partial LOH mutation and a 4.5-fold higher frequency of (− − +) to (+ − −) partial LOH mutations suggests the existence of a haploinsufficient region for cell proliferation distal to Ncam. Quantitative Southern blot data (not shown) also support this hypothesis.

DISCUSSION

A mutagenesis protocol integrating inbred strain variation, genetic mapping, classic germ-line mutagenesis, and ES cell technology was assayed for the ability to generate mutations in the mouse essential for studying fundamental biological questions. Specifically, the efficiency of inducing deletion complexes in the mouse genome by x-ray mutagenesis in ES cells was tested.

Previous mutagenesis at the Hprt locus indicated that radiation-induced deletions could be recovered at Hprt; although, the extent of the deletions was limited and dependent on cell type (36). Deletions isolated here in ES cells covered <3 cM and most likely <1 cM based on molecular characterization with Hprt-linked markers. These data are similar to radiation-induced deletions described in human primary fibroblasts in that the deletions appeared to be limited to a small region (17). Analysis of the ES-cell deletions with conserved sequences between mouse and human could be used to determine whether in fact the maximum viable deletion size was the same in these two cell types. These data would indicate that genes required for normal cell proliferation probably are conserved between mouse and human. In addition, clear mutation induction after mutagen exposure in combination with molecular analysis indicated that the mutation spectra were mutagen dependent, with nearly half the x-ray-induced mutations classified as deletions, whereas the majority of UV-light-induced mutations were intragenic. Although the molecular analysis did not establish a molecular basis for the intragenic mutations, the mutation spectra suggested that x-rays and UV light induce the same type of mutations in ES cells as other cell types in vitro (45).

Molecular analysis of the autosomal Ncam/tk mutations with polymorphic chromosome 9 markers was consistent with a large fraction of the x-ray-induced mutations being interstitial deletions that extended over approximately one-half of chromosome 9, whereas mutations consistent with terminal deletions also were recovered at lower frequencies. Cytogenetic analysis with a chromosome 9-specific paint was also consistent with this conclusion, although, as has been observed elsewhere (46), more complex rearrangements can occur. The extent of the hypothesized interstitial deletions and relative frequency of terminal deletions could be explained by a haploinsufficient region distal to Ncam required for ES cell proliferation. Dosage analysis at the Ncam locus was consistent with this hypothesis in that mutations with LOH distal to D9Mit207 had two copies of the remaining Ncam allele, including complete LOH mutations. The cytogenetic analysis was also consistent with a putative haploinsufficient region in that a mutation analyzed with an apparent deletion of this region had duplicated the homologous chromosome. Because interstitial deletions recovered at Ncam/tk did not overlap with those isolated in the specific locus test at Myo5a/Bmp5 distal to Ncam (47), both a proximal and distal boundary for this putative haploinsufficient region are defined by the extent of the deletions isolated at both loci, limiting this region to no more than 6.6 cM. This may be one of the two haploinsufficient regions previously described on chromosome 9 based on lethality around implantation of embryos deficient for either half of the chromosome (48). As has been observed at other autosomal loci including Aprt (49), complete LOH mutations were prevalent in the spontaneous mutations at Ncam/tk. Taken in context with the haploinsufficient hypothesis, the probable cause is reduction to homozygosity caused by chromosome loss and reduplication.

Comparison of the mutation frequencies and spectra at Hprt and Ncam/tk indicate that both were clearly locus dependent. However, mutation frequencies in cell lines at the same locus also varied, indicating cell line dependence as well. This finding could reflect differences in growth rate or differentiation state (50) of the ES cell lines tested. To take into account this variability, the calculated overall mutation frequencies were based on multiple mutagenized populations, various selection conditions, and all cell lines tested. Overall, the deletion frequency at the two loci varied from ≈7 to 50/106 at Hprt and Ncam/tk after x-ray exposure. Based on this frequency and optimal selection conditions, a mutagenized population from 21 to 150 × 106 ES cells selected on 5–35 100-mm tissue culture plates would be expected to yield 25 deletions, i.e., a deletion complex. This expectation is in dramatic contrast to the 20,000 mice that on average would have to be screened to isolate a similar number of deletions with the most efficient germ-line mutagenesis protocol (12). In addition, because the majority of the genome is autosomal, most loci would be expected to have a deletion frequency similar to that observed at Ncam/tk and therefore would require only three times as many cells used in a typical gene targeting experiment to generate a potential deletion complex. This estimate was consistent with similar experiments performed in the t region on chromosome 17 where the observed deletion frequency was nearly identical to that at Ncam/tk; however, the more limited molecular analysis of those deletions indicated a minimum deleted interval of 7 cM (21), much smaller than seen at Ncam/tk. Although not demonstrated here, ES cells with a radiation-induced deletion have efficiently contributed to the germ-line of chimeras, allowing for the establishment of lines of mice with a specific deletion (21). As in all random mutagenesis, second site mutations may be present; however, removal of other mutations from the selected deletion genome can be performed by breeding and subsequent segregation of unlinked mutations.

In conclusion, x-ray mutagenesis at two loci in a highly polymorphic ES cell line allowed for efficient detection and isolation of deletions. The frequency of x-ray-induced deletions recovered at both loci indicates that this approach represents an efficient and accessible source of deletion complexes in the mouse.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Karen Gustashaw for assistance with the fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis and Drs. Cindy Faust and Scott Bultman for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to T.M. (HD26722 and NS32779) and J.W.T. (Training Grant HD07104).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Hprt

hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase

- Ncam

neural cell adhesion molecule

- ES

embryonic stem

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- GANC

gancyclovir

- FIAU

1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil

- TK

thymidine kinase

- 6-TG

6-thioguanine

References

- 1.Russell W L. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1951;16:327–336. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1951.016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell L B, Montgomery C S, Raymer G D. Genetics. 1982;100:427–453. doi: 10.1093/genetics/100.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon M F, Morris T. Genet Res. 1966;7:12–17. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300009435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinchik E M, Russell L B. In: Genome Analysis Volume 1: Genetic and Physical Mapping. Davies K E, Tilghman S M, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1990. pp. 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gluecksohn-Waelsch S, Schiffman M B, Thorndike J, Cori C F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:825–829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niswander L, Yee D, Rinchik E M, Russell L B, Magnuson T. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1988;102:45–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinchik E M, Carpenter D A, Selby P B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:896–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinchik E M, Carpenter D A. Mamm Genome. 1993;4:349–353. doi: 10.1007/BF00360583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinchik E M, Carpenter D A, Long C L. Genetics. 1993;135:1117–1123. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.4.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell W L, Kelly E M, Hunsicker P R, Bangham J W, Maddux S C, Phipps E L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5818–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cattanach B M, Burtenshaw M D, Rasberry C, Evans E P. Nat Genet. 1993;3:56–61. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rinchik E M. Trends Genet. 1991;7:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90016-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas K R, Capecchi M R. Cell. 1987;51:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doetschman T, Maeda N, Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8583–8587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koller B H, Hagemann L J, Doetschman T, Hagaman J R, Huang S, Williams P J, First N L, Maeda N, Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8927–8931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartzberg P L, Goff S P, Robertson E J. Science. 1989;246:799–803. doi: 10.1126/science.2554496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris T, Masson W, Singleton B, Thacker J. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1993;19:9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01233950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C Y, Yandell D W, Little J B. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1992;18:77–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01233450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turker M S, Pieretti M, Kumar S. Mutat Res. 1997;374:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich W F, Miller J C, Steen R G, Merchant M, Damron D, Nahf R, Gross A, Joyce D C, Wessel M, Dredge R D, Marquis A, Stein L D, Goodman N, Page D C, Lander E S. Nat Genet. 1994;7:220–245. doi: 10.1038/ng0694supp-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You Y, Bergstrom R, Klemm M, Lederman B, Nelson H, Ticknor C, Jaenisch R, Schimenti J. Nat Genet. 1997;15:285–288. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mereau A, Grey L, Piquet-Pellorce C, Heath J K. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:713–719. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomasiewicz H, Ono K, Yee D, Thompson C, Goridis C, Rutishauser U, Magnuson T. Neuron. 1993;11:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90228-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yagi T, Ikawa Y, Yoshida K, Shigetani Y, Takeda N, Mabuchi I, Yamamoto T, Aizawa S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9918–9922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez-Solis R, Rivera-Perez J, Wallace J D, Wims M, Zheng H, Bradley A. Anal Biochem. 1992;201:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90347-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabinowitz J E, Rutishauser U, Magnuson T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6421–6424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans H H, Mencl J, Horng M F, Ricanati M, Sanchez C, Hozier J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4379–4383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavathas P, Bach F H, DeMars R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4251–4255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mei N, Kunugita N, Nomoto S, Norimura T. Mutat Res. 1996;357:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thacker J. Mutat Res. 1985;150:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(85)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trott D A, Cuthbert A P, Todd C M, Themis M, Newbold R F. Mol Carcinogen. 1995;12:213–224. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940120406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caskey C T, Kruh G D. Cell. 1979;16:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huttner E, Speit G, Lambert B, Hou S M, Holzapfel B, Tates A. Mutat Res. 1996;359:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1161(96)90011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aghamohammadi S Z, Morris T, Stevens D L, Thacker J. Mutat Res. 1992;269:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(92)90155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao C Y, Ma A H, Evans H H, Horng M F, Mencl J, Hui T E, Sedwick W D. Mutat Res. 1995;326:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)00152-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuscoe J C, Nelsen A J, Pilia G. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1994;20:39–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02257484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbs R A, Nguyen P N, Edwards A, Civitello A B, Caskey C T. Genomics. 1990;7:235–244. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monnat R J J, Hackmann A F M, Chiaverotti T A. Genomics. 1992;13:777–787. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90153-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris T, Thacker J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1392–1396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson S L, Jones I R, Fuscoe J C, Burkhart-Schultz K, Grosovsky A J. Radiat Res. 1995;141:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicklas J A, Hunter T C, O’Neill P, Albertini R J. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:267–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park M S, Hanks T, Jaberaboansari A, Chen D J. Radiat Res. 1995;141:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossiter B J F, Fuscoe J C, Muzny D M, Fox M, Caskey C T. Genomics. 1991;9:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90249-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dietrich W, Katz H, Lincoln S E, Shin H S, Friedman J, Dracopoli N C, Lander E S. Genetics. 1992;131:423–447. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichenauer-Kaligis E G R, Thijssen J, den Dulk H, van de Putte P, Giphart-Gassler M, Tasseron-de Jong J. Mutat Res. 1995;326:131–146. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson P, Morris T, Savage J, Thacker J. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1993;64:39–45. doi: 10.1159/000133557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton B A, Frankel W N, Kerrebrock A W, Hawkins T L, FitzHugh W, Kusumi K, Russell L B, Mueller K L, van Berkel V, Birren B W, Kruglyak L, Lander E S. Nature (London) 1996;379:736–739. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baranov V S. Genet Res. 1983;41:227–239. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300021303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinedinst D K, Drinkwater N R. Mutat Res. 1991;250:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90193-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sehlmeyer U, Wobus A M. Mutat Res. 1994;324:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]