Abstract

Rapamycin has previously been shown to be efficacious against intracerebral glioma xenografts and to act in a cytostatic manner against gliomas. However, very little is known about the mechanism of action of rapamycin. The purpose of our study was to further investigate the in vitro and in vivo mechanisms of action of rapamycin, to elucidate molecular end points that may be applicable for investigation in a clinical trial, and to examine potential mechanisms of treatment failure. In the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10 (PTEN)-null glioma cell lines U-87 and D-54, but not the oligodendroglioma cell line HOG (PTEN null), doses of rapamycin at the IC50 resulted in accumulation of cells in G1, with a corresponding decrease in the fraction of cells traversing the S phase as early as 24 h after dosing. All glioma cell lines tested had markedly diminished production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) when cultured with rapamycin, even at doses below the IC50. After 48 h of exposure to rapamycin, the glioma cell lines (but not HOG cells) showed downregulation of the membrane type–1 matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) invasion molecule. In U-87 cells, MMP-2 was downregulated, and in D-54 cells, both MMP-2 and MMP-9 were downregulated after treatment with rapamycin. Treatment of established subcutaneous U-87 xenografts in vivo resulted in marked tumor regression (P < 0.05). Immunohistochemical studies of subcutaneous U-87 tumors demonstrated diminished production of VEGF in mice treated with rapamycin. Gelatin zymography showed marked reduction of MMP-2 in the mice with subcutaneous U-87 xenografts that were treated with rapamycin as compared with controls treated with phosphate-buffered saline. In contrast, treatment of established intracerebral U-87 xenografts did not result in increased median survival despite inhibition of the Akt pathway within the tumors. Also, in contrast with our findings for subcutaneous tumors, immunohistochemistry and quantitative Western blot analysis results for intracerebral U-87 xenografts indicated that there is not significant VEGF production, which suggests possible deferential regulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in the intracerebral compartment. These findings demonstrate that the complex operational mechanisms of rapamycin against gliomas include cytostasis, anti-VEGF, and anti-invasion activity, but these are dependent on the in vivo location of the tumor and have implications for the design of a clinical trial.

Classic phase 1 and 2 clinical trials determine the safety and efficacy of agents by evaluating indirect end points based on clinical assessments of toxicity and response, respectively. Reliance on these indirect end points leaves unanswered important questions such as whether the drug actually reaches the tumor and whether it alters the biology of the tumor. Consequently, investigators have proposed revising the standard clinical design of brain tumor trials to also include assessments of molecular targets to optimize dose and to determine efficacy (Lang et al., 2002). For these trials to be successful, however, preclinical studies must be aimed at defining the appropriate molecular end points and developing clinically applicable assays to assess these end points (Lang et al., 2002). A molecular approach makes more efficient use of animal studies given the frequent observation that efficacy in animals only rarely correlates with efficacy in humans. Because several groups have proposed evaluating rapamycin, or one of its derivatives, as a potential treatment for patients with malignant gliomas, we explored the molecular targets of rapamycin in order to determine which ones could be used as end point(s) in molecular target–based, early-phase clinical trials.

Rapamycin has been recognized as an antineoplastic agent and is a potent inhibitor of tumor cell growth (Sehgal et al., 1975; Supko and Malspeis, 1994), specifically inhibiting the Ser-Thr kinase activity of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)3 FKBP-rapamycin-associated protein (FRAP) (Neshat et al., 2001; Price et al., 1992), a signaling molecule that links extracellular signaling to protein translation (Dilling et al., 1994). Activation of growth factor or cytokine receptors results in the sequential activation of PI3 kinase (PI3K), PDK1, Akt/PKB, and mTOR-FRAP. Treatment of cells with rapamycin leads to the dephosphorylation and inactivation of p70S6 kinase and 4EBP1. Dephosphorylation of 4EBP1 results in the binding to e1F4E, which inhibits translation. The tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10 (PTEN) downregulates Akt activity, and PTEN-null cell lines expressing high levels of Akt, such as U-87, U-251, SF-539, and SF-295, are sensitive to rapamycin inhibition of mTOR-FRAP at an IC50 of less than 0.01 μM in vitro (Neshat et al., 2001). Although in established subcutaneous U-87 glioma tumors, doses of rapamycin that inhibit mTOR (1 mg/kg administered i.p. once every 3 days) are insufficient for suppression of growth (Eshleman et al., 2002), higher doses of rapamycin (1.5 mg/kg administered i.p. once daily) inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis (Guba et al., 2002). Furthermore, rapamycin has been shown to be efficacious against established intracerebral U-251 gliomas in a murine model. Specifically, mice treated with rapamycin intraperitoneally at 200, 400, and 800 mg/kg/injection had increased life spans of 67%, 47%, and 78%, respectively, compared to survival of untreated controls (Houchens et al., 1983), suggesting that rapamycin may be a promising agent against gliomas.

The purpose of our study was to further investigate the in vitro and in vivo mechanisms of action of rapamycin in order to elucidate molecular end points that may be applicable in early phase clinical trials and to examine potential mechanisms of treatment failure. This study demonstrates that rapamycin affects cytostasis, cell signaling, angiogenesis, and invasion in vitro. Although rapamycin in our model system demonstrated in vivo efficacy in the subcutaneous compartment, an increase in median survival was not seen in the intracerebral compartment, which indicates that the anatomical microenvironment influences the tumor response to rapamycin.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Cell Lines

The cell lines U-87, D-54, and HOG (provided for our study as a gift) are PTEN null and were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 medium (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, Va.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-BRL, Rockville, Md.). All cell lines tested negative for Mycoplasma contamination. Both U-87 and D-54 express high constitutive levels of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α,4 resulting in enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Drugs

Rapamycin (sirolimus; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and its derivative RAD001 [everolimus; 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl)-rapamycin; Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland] were stored at a concentration of 5 mg/ml and 10−2 M, respectively, in 100% ethanol at −20°C and were diluted in serum-free medium immediately prior to use. The oral formulation of RAD001 is provided as a microemulsion preconcentrate that has efficacy after oral dosing equivalent to that of rapamycin and has the same mode of action at the cellular and molecular level as rapamycin (Schuler et al., 1997). When compared to rapamycin, the in vitro activity of RAD001 is generally about two to three times lower (Schuler et al., 1997).

Murine Models and Tumor Formation

All animal studies were conducted with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Male 6- to 8-week-old nude mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were housed within an approved specific pathogen–free barrier facility maintained at the M.D. Anderson Isolation Facility in accordance with Laboratory Animal Resources Commission standards. Appropriate measures were taken to minimize animal discomfort, and appropriate sterile surgical techniques were utilized in tumor implantation and drug administration. Animals that became moribund or had necrotic tumors were compassionately euthanized.

To induce the subcutaneous tumors, logarithmically growing U-87 cells were injected into the right hind flank of nude mice at a dose of 1 × 106 cells per 200 μl. Treatment with rapamycin intraperitoneally at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day was begun when the majority of animals had palpable tumors (at day 5). Tumors were measured every other day, and tumor volumes (length × width2/2) were calculated on the basis of the tumors that grew in surviving mice.

To induce intracerebral tumor, U-87 cells (5 × 105) were engrafted into the caudate nucleus of athymic mice as previously described (Lal et al., 2000). We performed three independent experiments using 6 to 10 animals per group in each experiment. For the survival studies, treatment was started on day 3 after implantation of the U-87 cells, and mice were treated via oral gavage with RAD001, the derivative of rapamycin. To obtain tumors of sufficient size to perform the biological assays, treatment was started on day 7 after implantation of U-87 cells.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity

Cells in logarithmic growth at 80% confluency were harvested with trypsin-EDTA (0.5–0.2 g/liter) solution (GIBCO-BRL), washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and plated in triplicate in 96-well U-bottom plates at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/ml. Rapamycin was added at concentrations of 0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, 100, and 1000 ng/ml, and the plates were incubated at 38°C for 24 h. Counts of viable cells were determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion method.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells in logarithmic growth at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml were treated with rapamycin at doses of 0, 0.1, 1.0, and 10 ng/ml for U-87 cells; 0, 1.0, 10, and 100 ng/ml for D-54 cells; and 0, 100, and 1000 ng/ml for HOG cells. Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol, stained with 20 μg/ml of propidium iodide and 100 μg/ml of RNase A, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with appropriate gating on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.).

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lines or minced tumor tissue underwent protein extraction in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), leupeptin 0.2 g/ml, aprotinin 5 μg/ml, phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride 1 mM (Sigma), and 1% NP-40 (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was stored at −70°C after centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined by standard Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Equivalent amounts of protein extracts (20 μg/well) were subjected to 12.5% SDS–polyacrilamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel denaturing conditions and were immunoblotted with anti-VEGF (Sigma), anti–matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) (Sigma), anti-4EBP1 (Cell Signaling Technology, San Jose, Calif.), anti-α-tubulin (Sigma), or anti-β actin (Sigma). Fold increases in intensity of each band were scanned with a densitometer (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, N.J.), normalized to control β-actin or -tubulin, and analyzed by using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics).

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The glioma cells were treated with rapamycin in serum-free medium as previously described. Cell viability at the completion of the experiment was determined by trypan blue exclusion. The medium was collected and stored at −80°C and was not subjected to more than one freeze-thaw cycle prior to use. VEGF secretion was measured in duplicate samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumors removed from nude mice were fixed in 10% formalin solution for approximately 6 h at room temperature and then embedded in paraffin. Sections of paraffin-embedded tumors were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated, and then stained after endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by treating them with 3% H2O2 for 5 min at room temperature. Tissue staining was performed with the HRB-DAB system (R & D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibodies utilized were mouse anti-human VEGF (R & D Systems) at a 1:50 dilution or mouse anti-human membrane type–1 (MT1)-MMP (R & D Systems) at a 1:22 dilution. The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, and the tumor sections were examined with a Nikon microscope.

Gelatin Zymography

The supernatant from glioma cell lines treated with medium containing rapamycin or medium alone was harvested and stored at −80°C prior to use. The samples (each containing 15 μg of supernatant protein) were fractionated by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel containing 10% SDS and gelatin (Bio-Rad). To determine in vivo MMP activity, tumor fragments (10 mm3 each) were cut from the tumor, weighed, and extracted with 2 × SDS sample buffer (1:2 w/v). After extraction for 2 h at room temperature, samples were diluted 2-fold with 1 × SDS sample buffer and homogenized by repeated pipetting. The solubilized material was separated from the pellet by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min, and aliquots of these supernatants were analyzed by gelatin zymography (20 μl/sample lane). Coomassie blue staining confirmed equivalent protein loading of samples on gels.

SDS was subsequently removed from the gels with 2.5% Triton X-100, and they were incubated overnight at 37°C in a solution containing 50 mM Tris base, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% Brij-35 (30%). The gels were then stained with 0.5% Coomassie blue in 40% methanol and 10% acetic acid for 2 h at room temperature with agitation and then destained with 40% methanol and 10% acetic acid to reveal clear bands of proteolytic activity.

MT1-MMP Analysis

Cell lines treated as previously described with rapamycin or media alone were washed with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumen (BSA) and stained for 40 min with 10 μg/ml of rabbit control IgG or an antibody against the hinge domain of MT1-MMPs (Sigma). After washing, the cells were stained with the secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated F(ab′)2 fragment of goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) for 30 min. Cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan with cell population gates for negative control set by using cells stained with rabbit IgG.

Cell Invasion Assay

Tumor cell invasion was measured with Matrigel Invasion Chambers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif.). The glioma cell lines in 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) were added at a concentration of 5 × 104 to the upper chamber, and 10% FCS was used in the lower chamber to induce cell migration. Rapamycin was added to the upper chamber at concentrations spanning the IC50. Duplicate filters were used for each treatment, and all the cells on each filter were counted by using an inverted microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Spearman rank correlation coefficient analysis was used to analyze the VEGF ELISA data. A linear model relating the VEGF values to log dose, time, and cell line was used to include a three-way interaction as well as all nested two-way interactions. Residual analyses demonstrated that the model fit the data. A two-sample t test assuming equal variances between groups was used to determine the statistical significance on quantitative Western blot densitometry. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the volumes of subcutaneous tumors between rapamycin-treated and untreated groups. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

Results

In Vitro Studies

Determination of IC50 of rapamycin for glioma cell lines

To determine whether there was a direct cytostatic effect of rapamycin on the growth of U-87, D-54, and HOG cells, these lines in logarithmic growth were exposed to 0 to 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and counted; the IC50 for U-87, D-54, and HOG was 0.65, 75, and > 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin, respectively.

Rapamycin induces G1 arrest in glioma cell lines

To determine if rapamycin induced cell cycle arrest, D-54, U-87, and HOG cell lines were treated for 24 and 48 h with medium alone or with medium containing rapamycin at the respective IC50 dose determined for each line. Flow analysis cytometry was performed to determine the fraction of cells in subG0/G1 (apoptosis), G1, G2 and S phases (Table 1). Treatment of the D-54 and U-87 cell lines with rapamycin resulted in the accumulation of cells in the G1 compartment, indicating that rapamycin acts in a cytostatic manner. Treatment of the HOG cell line, even with maximum doses of rapamycin, failed to induce cytostasis.

Table 1.

Flow cytometric analysis results showing rapamycin-induced G1 arrest in D-54 and U-87 glioma cells but not in HOG oligodendroglioma cells*

| Cell Line | Time | Rapamycin Dose (ng/ml) | % Sub-G0/G1 | % G1 | % G2 | % S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-54 | 24 | 0 | <1 | 52.4 | 10.7 | 36.9 |

| D-54 | 24 | 100 | <1 | 64.3 | 9.4 | 26.2 |

| D-54 | 48 | 0 | <1 | 40.3 | 16.1 | 43.6 |

| D-54 | 48 | 10 | <1 | 68.1 | 5.6 | 26.4 |

| U-87 | 24 | 0 | <1 | 47.0 | 8.2 | 44.7 |

| U-87 | 24 | 1 | <1 | 59.2 | 32.3 | 8.5 |

| U-87 | 48 | 0 | <1 | 57.7 | 25.1 | 17.2 |

| U-87 | 48 | 100 | <1 | 67.8 | 24.4 | 7.8 |

| HOG | 24 | 0 | <1 | 38.3 | 31.1 | 30.6 |

| HOG | 24 | 1000 | <1 | 35.2 | 27.2 | 37.6 |

| HOG | 48 | 0 | <1 | 55.1 | 28.7 | 16.2 |

| HOG | 48 | 1000 | <1 | 52.6 | 26.8 | 20.6 |

Cell lines were treated with rapamycin at the IC50 for 24 h, the DNA content was measured measured by flow cytometry after cells were stained with propidium iodide, and and the proportions of cells in G1, G2, and S phases of the cell cycle were computed. The experiment was replicated twice at two different time points with similar results.

RAD001 (everolimus) suppresses the phosphorylation of p-4EBP1, a downstream signal molecule of the Akt pathway

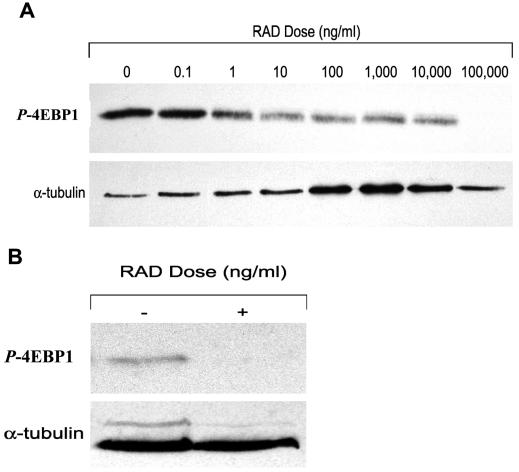

To determine whether the rapamycin derivative RAD001 could decrease the phosphorylation of the downstream signaling molecule p-4EBP1 of the Akt pathway, U-87 cells were cultured for 24 h with doses of RAD001 spanning the IC50, and the amount of p-4EBP1 was quantitated on Western blot. With volumetric band density normalized to a maintenance protein (α-tubulin), RAD001 significantly diminished production of p-4EBP1 (Fig. 1A). This data is consistent with previously published reports that the Akt pathway is inhibited by rapamycin.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative Western blot analysis demonstrating inhibition of p-4EBP1 by RAD001. U-87 (A) or U-87 intracerebral tumors (B) were treated with the derivative of rapamycin, RAD001, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Equivalent amounts of protein extracts (20 g/well) were subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel denaturing conditions and were immunoblotted with anti-4EBP1 and anti-tubulin. Fold increases in intensity of each band were scanned with a densitometer and normalized to control-tubulin. RAD001 inhibited the phosphorylated form of 4EBP1, the downstream signaling molecule of Akt, both in vitro and in vivo.

Rapamycin suppresses the secretion of VEGF in glioma cell lines

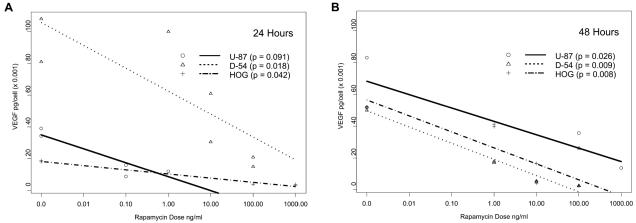

To determine whether rapamycin could decrease the production of VEGF in vitro, we cultured glioma cells for 24 and 48 h with doses of rapamycin spanning the IC50, and we determined the VEGF concentration by ELISA. To control for the effect of diminished cell number as the basis for diminished VEGF production, cell counts at each time point were determined, and VEGF secretion per cell was calculated. At 24 and 48 h there was a markedly diminished production of VEGF by all glioma cell lines at rapamycin doses significantly below the IC50. Even though an IC50 could not be determined for the HOG cell line, dramatic inhibition of VEGF production was seen after 48 h of exposure to rapamycin at 10 ng/ml (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Downregulation of VEGF in rapamycin-treated glioma cells. Glioma cell lines (D-54 and U-87) and HOG oligodendroglioma cells were treated with the indicated doses of rapamycin for 24 h (panel A) and 48 h (panel B), and their VEGF production was determined by ELISA assay. Diminished cell numbers were accounted for by calculating VEGF production per viable cell. The experiment was replicated in duplicate samples over two different time points with similar outcomes. A linear model relating the VEGF values to log dose, time, and cell line was used to include a three-way interaction as well as all nested two-way interactions. Residual analyses demonstrated that the model fit the data. The P-value for the three-way interaction was 0.05, that for the two-way interaction between dose and time was 0.47, that for dose and cell line was 0.033, and that between time and cell line was < 0.0001.

Rapamycin inhibits invasion and downregulates MMPs

The enzymatic activities of MT1-MMP and MMP-2 contribute to the integrity of the extracellular matrix in the brain, and hydrolysis of the brain’s extracellular matrix allows glioma cells to invade normal brain tissue. To determine whether rapamycin downregulates MMPs, we treated the cell lines U-87, D-54, and HOG in vitro with rapamycin for 48 h, and we used flow cytometry to quantify the amount of the membrane-bound MMP, MT1-MMP, after the cell line had been exposed to a monoclonal antibody to MT1-MMP (see Materials and Methods). After 48 h of treatment with 10 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml of rapamycin, respectively, the glioma cell lines U-87 and D-54 showed downregulation of MT1-MMP (Table 2). In contrast, there were minimal levels of MT1-MMP expressed in the HOG cell lines, which did not appear to be affected by treatment with 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin (data not shown).

Table 2.

Flow cytometric analysis results showing downregulation of the invasion molecule MT1-MMP by rapamycin on U-87 and D-54 cells*

| Cell Line | Rapamycin Dose (ng/ml) | % MTI-MMP Positive Cells |

|---|---|---|

| D-54 | 0 | 15.6 |

| D-54 | 100 | 7.25 |

| U-87 | 0 | 9.9 |

| U-87 | 10 | 3.45 |

| HOG | 0 | 3.95 |

| HOG | 1000 | 8.43 |

The cells were treated for 48 h with rapamycin. The cells were then incubated with an isotype control antibody or an MT1-MMP-specific antibody with an FITC-conjugated fragment of goat anti-rabbit IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Positive isotype control staining was less than 1.9%.

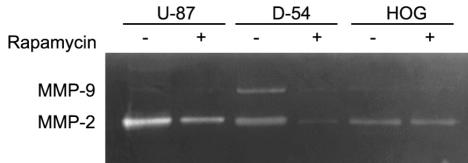

Because MT1-MMP-expressing glioma cells can activate proMMP-2, with the resulting enzymatic activity of MMP-2 facilitating tumor invasion of normal brain, we determined if rapamycin downregulated the secretory invasion molecules MMP-2 and MMP-9. The glioma cell lines were treated with rapamycin for 48 h, and for each cell line, the supernatant was harvested, the protein was quantitated, and gelatin zymography was performed. In the U-87 glioma line, the invasion molecule MMP-2 was downregulated by treatment with 10 ng/ml of rapamycin; however, significant quantities of MMP-9 were not present in untreated cells. In the D-54 cell line, both MMP-2 and MMP-9 were present and downregulated by 100 ng/ml of treatment with rapamycin. In the HOG cell line, only MMP-2 was present, and it did not appear to be altered by treatment with 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Gelatin zymograph showing downregulation of the invasion molecules MMP-2 and MMP-9 by rapamycin. The glioma (U-87 and D-54) and oligodendroglioma (HOG) cell lines were treated for 48 h with rapamycin. The supernatant was harvested from each respective cell line, and 15 μg of protein from each supernatant was fractionated by gelatin zymography. Untreated (medium only) U-87 cells express MMP-2 but little MMP-9. U-87 cells treated with 10 ng/ml of rapamycin show MMP-2 downregulation. Untreated (medium only) D-54 cells express both MMP-2 and MMP-9. However, D-54 cells treated with 100 ng/ml of rapamycin demonstrated downregulation of both MMP-2 and MMP-9. Untreated (medium only) HOG cells expressed only MMP-2, and when this cell line was treated with the maximal dose of 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin, there was no change in MMP-2 expression.

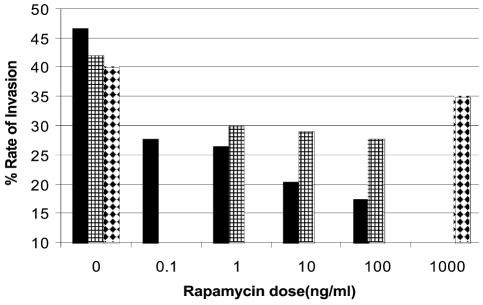

To determine if rapamycin inhibits in vitro invasion, glioma cell lines were treated with rapamycin for 24 h. In the U-87 and D-54 cell lines, invasion was inhibited with rapamycin concentrations below the IC50. In contrast, in the HOG cell line, even treatment with 1000 ng/ml of rapamycin failed to alter in vitro invasion (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

In vitro invasion assay demonstrating that rapamycin inhibits invasion. U-87, D-54, and HOG cell lines were treated for 24 h with rapamycin. The glioma cells lines in 5% FCS were added at a concentration of 5 × 104 to the upper chamber, and 10% FCS was used in the lower chamber to induce cell migration. Rapamycin was added to the upper chamber at concentrations spanning the IC50. Invasion was inhibited with rapamycin at concentrations less than the IC50 in both the U-87 and D-54 cell lines. However, even at 1000 ng/ml, rapamycin did not significantly inhibit the invasion of the HOG cell line. Solid bars, U-87; bars with small squares, D-54; white bars with black diamonds, HOG.

In Vivo Studies: Subcutaneous Model

Rapamycin suppresses growth of subcutaneous tumors

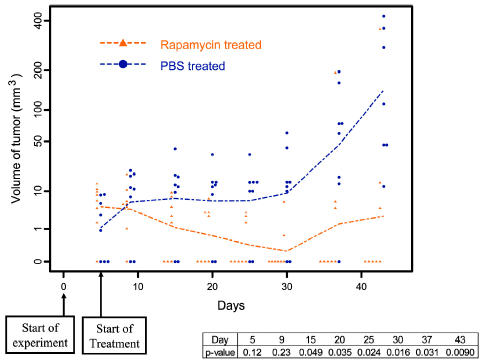

To determine if rapamycin was efficacious in the treatment of established tumors, subcutaneous U-87 tumors were treated with 1.5 mg/kg/day of rapamycin for 45 days. In 63% (n = 8) of established tumors treated with rapamycin, there was regression with no evidence of residual tumor at the conclusion of the experiment. In all U-87 tumors treated with PBS alone (n = 8), there was no evidence of regression, and all mice had large tumors at the conclusion of the experiment (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Changes with time in the volume of subcutaneous U-87 tumors in nude mice with and without rapamycin treatment. Nude mice with established tumors (from subcutaneous injection of U-87 glioma cells) were treated daily with rapamycin at 1.5 mg/kg/day. There was regression in 63% (n = 8) of these tumors, with no evidence of residual tumor at the conclusion of the experiment (day 50) (P < 0.05). In contrast, all mice treated with PBS alone (n = 8) had large tumors at the conclusion of the experiment.

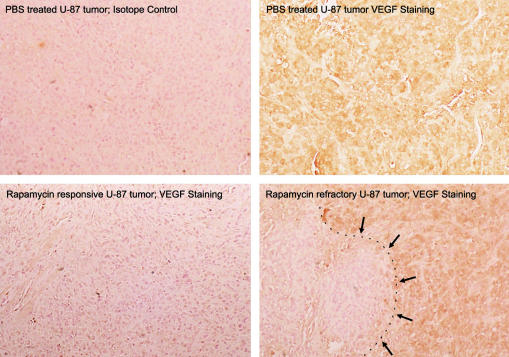

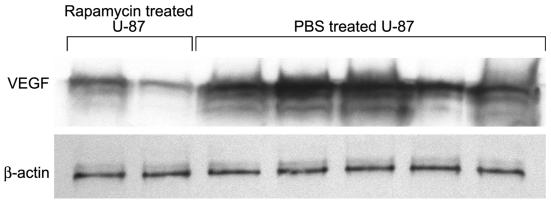

Rapamycin inhibits in vivo VEGF

To verify that rapamycin downregulates VEGF production in vivo we treated subcutaneous U-87 tumors for 45 days with 1.5 mg/kg/day of rapamycin. Subsequent immunohis tochemical studies demonstrated that there was diminished VEGF production in tumors treated with rapamycin (Fig. 6). Determination of volumetric band density normalized to a maintenance protein (β-actin) on Western blot revealed that VEGF levels in tumors that were treated with rapamycin were lower (mean = 2.2; SD = 1.46) than those in tumors that were treated with PBS (mean = 5.3; SD = 1.27; P = 0.037) (Fig. 7). VEGF production did not appear to vary among the various tumor sizes in the PBS treatment group. Interestingly, the one rapamycin-treated U-87 tumor that achieved a size similar to the PBS-treated control tumors had a localized area of diminished VEGF production but had discrete areas of high VEGF production, possibly representing a mechanism of chemotherapy resistance. This tumor remained small volumetrically until day 30, at which point growth increased 60-fold in 15 days.

Fig. 6.

Diminished immunohistochemical staining for vascular endothelial lial growth factor in subcutaneous U-87 cell tumors in nude mice mice after rapamycin treatment. Nude mice with established subcutaneous U-87 cell tumors were treated with rapamycin, and after 45 days of of treatment, the experiment was terminated and the tumors were harvested ted. Paraffin-embedded sections of the tumors were stained with anti-VEGF antibody, and visualization employed the strepavidin-horseradish adish peroxidase system. In the lower right-hand panel, in the only peroxidase the lower right hand panel, the only U-87 tumor treated with rapamycin that attained a size similar to control-treated tumors, there was an area that was negative for VEGF VEGF staining (denoted by arrows), but the majority of the tumor demonstrated areas of high VEGF production (original magnification × 250).

Fig. 7.

Quantitative Western blot analysis demonstrating decreased VEGF production in vivo. Nude mice with established tumors (from subcutaneous injection of U-87 glioma cells) were treated daily with rapamycin at 1.5 mg/kg/day, and after 45 days of treatment, the tumors were harvested. The tumors were minced and underwent protein extraction. Equivalent amounts of protein extracts (20 μg/well) were subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel denaturing conditions and were immunoblotted with anti-VEGF and anti-β-actin. Fold increases in intensity of each band were scanned with a densitometer and normalized to control β-actin. Rapamycin inhibited VEGF production in vivo.

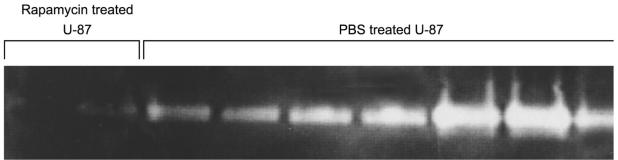

Rapamycin inhibits in vivo metalloproteinases

To determine if rapamycin modulated MMPs in vivo, subcutaneous U-87 tumors were treated with rapamycin and formalin fixed. Immunohistochemical staining failed to demonstrate dramatic changes in the level of MT1-MMP in U-87 tumors treated in vivo with rapamycin as compared to U-87 tumors treated with PBS. MT1-MMP staining was most prominent at the tumor periphery and appeared slightly more intense in U-87 tumors treated with PBS than in those treated with rapamycin (data not shown). Because MT1-MMP activity is necessary for the activation of proMMP-2, zymography was performed to identify the status of MMP-2 in U-87 tumors. Among rapamycin-treated subcutaneous U-87 tumors large enough to analyze 45 days after tumor implantation (n = 3), there was a marked reduction of MMP-2 (seen by gelatin zymography) as compared with the U-87 tumors treated with PBS alone (Fig. 8). The one rapamycin-treated tumor that escaped growth suppression did not show upregulation of MMP-2. These results are consistent with our in vitro data, thus confirming that rapamycin has an effect on MMPs.

Fig. 8.

Gelatin zymograph showing diminished production of MMP-2 in subcutaneous U-87 cell tumors in nude mice after rapamycin treatment. Nude mice with established subcutaneous U-87 cell tumors were treated with rapamycin, and after 45 days of treatment, the experiment was terminated and tumors were harvested. The tumor proteins were extracted and analyzed by gelatin zymography. Few rapamycin-treated U-87 tumors were of sufficient size to analyze (PBS-treated U-87 tumors were large and necrotic), but those that could be analyzed demonstrated diminished MMP-2 expression.

In Vivo Studies: Intracranial Model

RAD001 fails to suppress orthotopic U-87 growth

Secondary to Novartis’s interest in proceeding with a clinical trial for patients with malignant gliomas and since rapamycin has previously been demonstrated to be efficacious against established intracerebral xenografts, we elected to determine if RAD001 was efficacious in the treatment of established orthotopic U-87. Tumors were treated with 1.5 mg/kg/day or 5 mg/kg/day of the derivative of rapamycin, RAD001, starting three days after intracerebral implantation. In mice (n = 10/group) treated with 5 mg/kg or 1.5 mg/kg of RAD001 or with diluent, median survival was 30.5, 30.5, and 31 days, respectively, which was not statistically significant (data not shown). Three separate experiments produced similar results.

On quantitative Western blot analysis of orthotopically implanted U-87 tumors treated with RAD001, there was diminished p-4EBP1 (Fig. 1B). On immunohistochemistry, there was no discernable VEGF production within the intracerebral U-87 tumors, nor was there a difference with RAD001 treatment. Furthermore, Western blot analysis confirmed that there was no significant change in VEGF production. The intracerebral U-87 tumors treated with RAD001 demonstrated no significant changes in MMP-2 production on quantitative Western blot analysis or increased invasion characteristics by histology.

Discussion

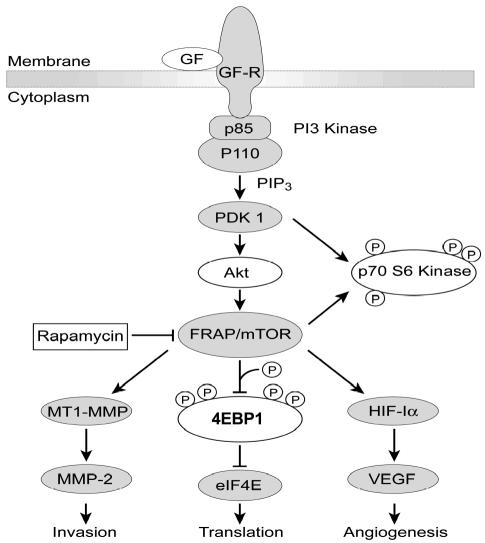

One of the purposes of our study was to further elaborate on the mechanism of action of rapamycin so that salient molecular end point(s) could be identified for a clinical trial of rapamycin for glioma patients (Fig 9). These end points could include cytostasis, cell signaling, angiogenesis, and invasion. In this study we show that rapamycin or its derivative RAD001 not only works as a cytostatic agent by the accumulation of cells in the cell cycle G1 compartment, with a corresponding decrease in the fraction of cells traversing the S phase, but also as an antiangiogenic (by inhibiting VEGF secretion) and an anti-invasion agent (by downregulating MT1-MMP, MMP-2, and MMP-9). Our data is consistent with findings of previously published studies indicating that mTOR-FRAP can regulate the activity of VEGF and invasion. Specifically, the signaling molecule mTOR-FRAP has previously been shown to be an upstream activator of HIF-1 (Hudson et al., 2002), and insulin has been shown to regulate HIF-1 action through PI3K/TOR-dependent pathways (Treins et al., 2002). The binding of HIF-1α to the VEGF promoter is a predominant enhancer of VEGF production (Fang et al., 2001; Tsuzuki et al., 2000), and rapamycin has been shown to inhibit the in vitro and in vivo production of VEGF (Brugarolas et al., 2003; El-Hashemite et al., 2003). In a recent article by Guba et al., rapamycin was shown to inhibit subcutaneous syngeneic adenocarcinomas by acting as an antiangiogenic agent by specifically inhibiting VEGF (Guba et al., 2002). Our studies confirm that downregulation of VEGF by rapamycin occurs in gliomas as well. In the VEGF ELISA, there was markedly diminished production of VEGF in all glioma cell lines, including the HOG cell line, in which rapamycin did not act in a cytostatic manner. Moreover, VEGF production was inhibited at rapamycin doses lower than the IC50 Furthermore, in subcutaneous U-87 tumors, treatment with rapamycin resulted in diminished production of VEGF.

Fig. 9.

Molecular targets of rapamycin. Activation of growth factor (GF) or cytokine receptors results in the sequential activation of PI3K, PDK1, Akt/PKB, and mTOR-FRAP. The tumor suppressor PTEN downregulates Akt activity (not shown). Rapamycin treatment of cells leads to the dephosphorylation (denoted by an encircled P) and inactivation of p70SB kinase and 4EBP1. The dephosphorylation of 4EBP1 results in binding to elF4E, which inhibits translation. Furthermore, the inhibition of mTOR-FRAP results in downregulation of HIF-1α and subsequent VEGF production. Finally, the inhibition of mTOR-FRAP also results in the downregulation of MT1-MMP, subsequent MMP-2 production, and resulting invasion.

VEGF has been shown to upregulate several invasion molecules, such as MMP-2, MMP-9, and MT1-MMP (Rooprai et al., 2000), and insulin-like growth factor-1 has been shown to regulate MMP-2 and its MT1-MMP-mediated activation by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (Zhang and Brodt, 2003). In the U-87 and D-54 glioma cell lines, the invasion molecule MMP-2 and both MMP-2 and MMP-9, respectively, were downregulated with rapamycin. Additionally, flow cytometric analysis showed downregulation of MT1-MMP in U-87 and D-54 after 48 h of treatment. Treatment of the subcutaneous U-87 tumors with rapamycin in vivo also resulted in the downregulation of MMP-2. Therefore, treatment with rapamycin in vitro and in the subcutaneous model results in a cytostatic response with downregulation of MMPs and VEGF.

In contrast to the inhibition of tumor growth with rapamycin in the subcutaneous model, mice with established intracerebral U-87 tumors that were treated with RAD001 showed no increase in median survival. Our findings are in contrast to previously published data, which demonstrated a significant increase in median survival of mice with established intracerebral U-251 cells treated with rapamycin (Houchens et al., 1983). These differences may be secondary to as-yet-undefined differences between rapamycin and RAD001 or differences in the tumor models. The difference in efficacy in the subcutaneous and intracerebral models may be secondary to the intracerebral microenvironment, possibly due to influences on hypoxic response and neovascularization, which influences tumor response. Intratumoral p-4EBP1 was inhibited in those mice treated with RAD001, an indication that the concentrations of RAD001 used in vivo were able to inhibit the Akt pathway. Blouw et al. (2003) have shown that HIF-1 -knockout-transformed astrocytes have diminished growth in the vessel-poor subcutaneous environment resulting in severe necrosis as well as reduced growth and vessel density, whereas cells of the same type that are placed into the vascular-rich brain parenchyma have enhanced growth and invasion. Our data is consistent with this previously published report. By immunohistochemistry and quantitative Western blot analysis, the intracerebral U-87 tumors failed to show any appreciable levels of VEGF in vivo, which indicated that additional or alternative mechanisms are involved in VEGF regulation intracerebrally. Although rapamycin may inhibit signal transduction and/or cellular proliferation, the inhibition of HIF-1α may not be a desired strategy to treat astrocytomas since they may adapt to becoming more invasive and infiltrative (Blouw et al., 2003). However, we did not see evidence of increased invasion by histology or upregulation of MMP-2 on Western blot of RAD001-treated intracerebral U-87 tumors. Previously, Houchens et al. demonstrated an increase in median survival in mice with intracerebral U-251 tumors treated with rapamycin, which is in contrast to our data with intracerebral U-87. The difference in results may be, in part, due to differential dosing amount and interval of rapamycin administration, model systems, and/or the underlying molecular status of the tumors.

Given the lack of concordance between murine models and human efficacy, murine model systems are perhaps best utilized for establishing appropriate molecular end points, but these will require validation in human subjects. A proposed clinical trial could begin with a stereotactic biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and establish a baseline of the molecular targets, including p-4EBP1, VEGF, HIF-1α, and MMP-2. After administration of rapamycin or RAD001, the tumor could be removed for analysis of pharmacokinetic and drug-related molecular changes. In the scenario of treatment failure, re-resection or biopsy could establish definitely if failure is occurring through the HIF-1α/VEGF pathway. If this is a mechanism(s) of treatment failure, combination therapy with an anti-VEGF agent may be considered. In conclusion, our data suggest that clinical trials that incorporate only a limited molecular target such as a signal transduction molecule may not necessarily correlate with efficacy and will be inadequate to assess treatment failures and future combination chemotherapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank David M. Wildrick for editorial assistance, Hyung-Woo Kim for statistical analysis, and Jeffrey S. Weinberg and Mark R. Gilbert for thoughtful commentary. The oligodendroglioma cell line, HOG, was provided through the courtesy of Ken Aldalpe of The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Supported by The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center National Institutes of Health Core Grant P30 CA16672, the Bullock Research Foundation, and the Elias Family Fund for Brain Tumor Research.

Abbreviations used are as follows: BSA, bovine serum albumin; CD3, T cell type I transmembrane protein; EDTA, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FCS, fetal calf serum; FRAP, FKBP-rapamycin-associated protein; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; IC50, inhibitory concentration 50; IL-2, interleukin 2; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MT1, membrane type–1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PI3K, PI3 kinase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; SPF, sterile, pathogen free; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Personal communication, Candelaria Gomez-Manzano, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, September 15, 2004.

References

- Blouw B, Song H, Tihan T, Bosze J, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Johnson RS, Bergers G. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG., Jr TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilling MB, Dias P, Shapiro DN, Germain GS, Johnson RK, Houghton PJ. Rapamycin selectively inhibits the growth of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma cells through inhibition of signaling via the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1994;54:903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hashemite N, Walker V, Zhang H, Kwiatkowski DJ. Loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 induces vascular endothelial growth factor production through mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5173–5177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman JS, Carlson BL, Mladek AC, Kastner BD, Shide KL, Sarkaria JN. Inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin sensitizes U87 xenografts to fractionated radiation therapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7291–7297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Yan L, Shing Y, Moses MA. HIF-1alpha-mediated up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, independent of basic fibroblast growth factor, is important in the switch to the angiogenic phenotype during early tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5731–5735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, Koehl G, Flegel S, Hornung M, Bruns CJ, Zuelke C, Farkas S, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Geissler EK. Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by antiangiogenesis: Involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:128–135. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchens DP, Ovejera AA, Riblet SM, Slagel DE. Human brain tumor xenografts in nude mice as a chemotherapy model. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983;19:799–805. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, Otterness DM, Loomis DC, Kaper F, Giaccia AJ, Abraham RT. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7004–7014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7004-7014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S, Lacroix M, Tofilon P, Fuller GN, Sawaya R, Lang FF. An implantable guide-screw system for brain tumor studies in small animals. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:326–333. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.2.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang FF, Gilbert MR, Puduvalli VK, Weinberg J, Levin VA, Yung WK, Sawaya R, Fuller GN, Conrad CA. Toward better early-phase brain tumor clinical trials: A reappraisal of current methods and proposals for future strategies. Neuro-Oncol. 2002;4:268–277. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/4.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, Stiles B, Thomas G, Petersen R, Frost P, Gibbons JJ, Wu H, Sawyers CL. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10314–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DJ, Grove JR, Calvo V, Avruch J, Bierer BE. Rapamycin-induced inhibition of the 70-kilodalton S6 protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1380182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooprai HK, Rucklidge GJ, Panou C, Pilkington GJ. The effects of exogenous growth factors on matrix metalloproteinase secretion by human brain tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:52–55. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler W, Sedrani R, Cottens S, Haberlin B, Schulz M, Schuurman HJ, Zenke G, Zerwes HG, Schreier MH. SDZ RAD, a new rapamycin derivative: Pharmacological properties in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation. 1997;64:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vézina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic, II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:727–732. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supko JG, Malspeis L. Dose-dependent pharmacokinetics of rapamycin-28-N N-dimethylglycinate in the mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;33:325–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00685908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Semenza GL, Van Obberghen E. Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27975–27981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204152200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki Y, Fukumura D, Oosthuyse B, Koike C, Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) modulation by targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha hypoxia response element VEGF cascade differentially regulates vascular response and growth rate in tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6248–6252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Brodt P. Type 1 insulin-like growth factor regulates MT1-MMP synthesis and tumor invasion via PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling. Oncogene. 2003;22:974–982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]