Abstract

High degrees of sequence and conformation complexity found in natural protein interaction interfaces are generally considered essential for achieving tight and specific interactions. However, it has been demonstrated that specific antibodies can be built by using an interface with a binary code consisting of only Tyr and Ser. This surprising result might be attributed to yet undefined properties of the antibody scaffold that uniquely enhance its capacity for target binding. In this work we tested the generality of the binary-code interface by engineering binding proteins based on a single-domain scaffold. We show that Tyr/Ser binary-code interfaces consisting of only 15–20 positions within a fibronectin type III domain (FN3; 95 residues) are capable of producing specific binding proteins (termed “monobodies”) with a low-nanomolar Kd. A 2.35-Å x-ray crystal structure of a monobody in complex with its target, maltose-binding protein, and mutation analysis revealed dominant contributions of Tyr residues to binding as well as striking molecular mimicry of a maltose-binding protein substrate, β-cyclodextrin, by the Tyr/Ser binary interface. This work suggests that an interaction interface with low chemical diversity but with significant conformational diversity is generally sufficient for tight and specific molecular recognition, providing fundamental insights into factors governing protein–protein interactions.

Keywords: 3D domain swapping, antibody engineering, combinatorial library, phage display, sequence diversity

Protein–protein interactions are of central importance in biology. Studies of the protein–protein interaction have demonstrated that, although the interfaces contain diverse amino acid composition, there is significant bias in this composition toward specific residues (1). The observation of such bias within the antigen-binding sites of antibodies recently prompted Sidhu and coworkers (2, 3) to explore the engineering of Fabs from restricted combinatorial libraries in which positions in the complementarity-determining regions are diversified to a combination of as few as two amino acids. In the most surprising example they used a binary combination of Ser and Tyr at a total of 28–36 positions to successfully obtain specific Fabs with a dissociation constant (Kd) of low nanomolar to low micromolar (2). Structural data showed a dominance of tyrosine in interface contacts, and from these and other studies (1, 4–7) the particular importance of Tyr as an interface-forming residue has emerged.

One might expect that the success of the Y/S binary Fabs may largely be due to the antibody-derived scaffold system, which has possibly evolved to acquire a uniquely high capacity for forming high-performance binding interfaces. Furthermore, the antigen-binding site of the antibody scaffold consists of six complementarity-determining region loops allowing a large number of residues to be involved in antigen binding. Thus, a fundamental question remains as to how general the Y/S binary interface is. It is not clear whether the binary code approach would equally work for a smaller scaffold that contains fewer positions for diversification. One might expect that the large number of Fab positions that can potentially form a binding interface may create a “forgiving” environment in which a combination of suboptimal amino acids in the interface can still generate tight and specific binders. In this work, to establish the generalizability of the binary code concept, we set out to define its limitation by applying this approach to a small, single-domain scaffold.

We have developed the 10th fibronectin type III domain of human fibronectin (FNfn10) as the molecular scaffold for engineering binding proteins (8, 9). FNfn10 is a small (≈94 aa) β-sandwich protein with an overall fold similar to that of the Ig domain (9). We constructed combinatorial libraries by diversifying three loops (BC, DE, and FG) (Fig. 1A) located at one end of FNfn10 and selected binders with desired characteristics. We have obtained such binding proteins, termed “monobodies,” with a Kd in the sub- to low-micromolar range from these libraries (8, 9). Although monobodies can be considered antibody mimics, both the size of the molecule and the number of surface loops available for diversification are considerably smaller than those for the Fab scaffold. Thus, the monobody system is a good platform for testing the minimalist limit of the Y/S binary interface.

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequences of Y/S monobodies. (A) A schematic drawing of the monobody scaffold. β-Strands A–G and the three loops that are diversified in the library are indicated. (B) Affinity and amino acid sequences of Y/S monobodies that were selected from the initial library selection. The number of occurrences for clones that appeared more than once is indicated in parentheses. Kd values determined by using yeast surface display are also shown. The sequences for the three loops are shown, with the numbering of Main et al. (20). Tyr, Ser, and the other amino acids are shaded in yellow, red, and gray, respectively.

Results

Engineering of Y/S Monobodies.

We designed a Y/S binary combinatorial library of monobody by introducing diversity at all positions in the three loops (BC, DE, and FG) (Fig. 1A) except for V27, where the V27S mutation significantly destabilized the protein. Based on the studies of synthetic antibody libraries that showed the importance of loop length variation for generating high-affinity binding (10), we varied the lengths of the three recognition loops in our library (6–10, 4–10, and 9–13 residues for the BC, DE, and FG loops, respectively). We ultimately constructed a single phage-display library containing 1010 independent clones. This library size is comparable to the total number of possible sequences encoded by the design (≈2 × 1010).

We sorted the Y/S monobody library against three protein targets, maltose-binding protein (MBP), human small ubiquitin-like modifier 4 (hSUMO4), and yeast small ubiquitin-like modifier (ySUMO) (Fig. 1B). After three rounds of phage-display library sorting, we transferred the enriched pools of monobody clones into the yeast-display format and performed one round of sorting. We were successful in obtaining binding clones to each of the targets.

The obtained Y/S monobodies (Fig. 1B) exhibited a clear and distinct consensus sequence for each target. The selected clones were unique to their cognate target, and monobodies to different targets show distinct loop length distributions (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that these monobodies are specific to their cognate targets, rather than nonspecific and “sticky.”

The selected monobodies used all of the designed lengths of the BC and FG loops except for a 12-residue-long FG loop, suggesting that the BC and FG loops do not have a preferred length. In contrast, the DE loop of all of the selected clones was four residues long, although its length was extensively diversified, suggesting a strong preference imposed by the scaffold. Also, five clones (ySUMO-55, MBP-74, MBP-76, MBP-79, and MBP-712) contain the nonmutated DE loop (amino acid sequence GSKS) (Fig. 1B), which originates from an incomplete mutagenesis reaction during library construction. This observation suggests that just two loops (BC and FG) of Y/S binary diversity may be sufficient for constructing a binding interface.

Amino acid sequences of individual clones identified at least two classes of monobodies for each target (Fig. 1B). The amino acid sequences of both BC and FG loops are distinctly different between different classes of monobodies (e.g., MBP-74 versus MBP-32), suggesting that these loops have mutual influence on each other's sequence and that they cooperatively form a binding interface.

Affinity and Specificity of Y/S Monobodies.

The Kd values of representative clones, as determined by using yeast surface display, ranged from 5 nM to 90 nM (Figs. 1B and 2A). The monobodies generally showed low levels of cross-reactivity to noncognate targets, but we also found clones that cross-react with multiple targets (e.g., hSUMO4–39 and MBP-73) (Fig. 2 C–E). The selected monobodies can discriminate hSUMO4 and ySUMO that have 40% sequence identity (Fig. 2 C and D). Furthermore, competition experiments showed that the affinity of MBP-74 to noncognate targets (hSUMO4, ySUMO, RNaseA, and cytochrome c) was at least 100 times weaker than that for its cognate target, MBP (data not shown). Target binding of MBP-74 was only mildly (≈50%) inhibited even by an addition of extremely concentrated Escherichia coli cell lysate (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the Y/S monobodies can achieve a good level of binding specificity.

Fig. 2.

Binding affinity and specificity of Y/S monobodies. (A) Titration curves for three MBP-binding monobodies tested by using yeast surface display. Binding of MBP to the monobodies displayed on the yeast surface is shown as a function of MBP concentration. The vertical axis indicates the level of MBP binding (PE fluorescence) normalized with respect to the level of monobody display (FITC fluorescence). (B) SPR sensorgrams for the interaction between the MBP-74 monobody and MBP. Sensorgrams of 10, 20, 50, and 100 nM MBP binding to the immobilized monobody are shown. The dashed and solid curves show the experimental data and the global fit of the 1:1 binding model, respectively. (C–E) Binding specificity of monobodies tested with three different targets and yeast surface display. The levels of binding to hSUMO4 (C), ySUMO (D), and MBP (E) were measured by using yeast surface display in a similar manner as in A. Monobodies 33 and 39 were selected with hSUMO4, monobodies 52 and 57 were selected with ySUMO, and monobodies 73, 74, and 76 were selected with MBP. Binding to the cognate target is indicated with an asterisk. Note that, because of different detection sensitivities of different targets, one can compare binding of different monobodies to the same target (i.e., data within a single panel), but not binding of one monobody to different targets (i.e., data across panels).

We then characterized binding affinity of MBP-74 and MBP-79 as purified proteins using surface plasmon resonance. They show sensograms that are consistent with a 1:1 binding mechanism (Fig. 2B), and their dissociation constants (135 and 108 nM, respectively) were consistent with those determined with yeast surface display (81 and 89 nM, respectively) (Fig. 1B).

X-Ray Structure Determination of a Y/S Monobody–Target Complex with Designed 3D Domain Swapping.

Our initial trials to crystallize MBP-binding monobodies in complex with MBP were unsuccessful. Thus, we developed a method in which a monobody is fused to its target with a short or no linker between them, which maintains a 1:1 stoichiometry. We hypothesized that such fused proteins would form an oligomer via 3D domain swapping (11) and that increasing the probability of higher order structure formation would enhance crystallization. We tested this strategy with the MBP-74 monobody and MBP. We made two different linker lengths (zero and three residues) between the C terminus of MBP and the N terminus of the monobody. Gel filtration revealed that the fusion protein with no linker formed predominantly an octamer, whereas the other with a three-residue linker formed a mixture of tetramer and octamer.

We successfully crystallized the MBP/MBP-74 fusion protein with no linker and determined its x-ray structure at a 2.35-Å resolution [supporting information (SI) Table 2]. The connecting segment between the MBP and monobody portions had well defined electron density (Fig. 3B), allowing us to unambiguously establish the connectivity of the two portions. Surprisingly, the fusion protein formed a continuous helical rod in the crystal with a fourfold screw axis along its length (Fig. 3 A and B), rather than an oligomer, indicating a structural rearrangement during crystallization.

Fig. 3.

The x-ray crystal structure of the MBP–monobody MBP-74 fusion protein. (A) A helical rod of the fusion proteins formed in the crystal along crystallographic 41-screw axis. Four symmetry-related copies of the fusion protein are shown in different colors, and the MBP and monobody portions are shown in lighter and darker shades, respectively. A schematic representation of the packing is also shown. (B) The binding complex of MBP (white) and monobody (blue) with the MBP fusion partner (cyan). A close-up image of the linker region with electron density is also shown. (C) The binding complex rotated ≈90° along the vertical axis with respect to that shown in B. (D) The epitope shown on the MBP surface. Red, orange, and yellow surfaces indicate those for atoms within 3.2, 4.0, and 5.0 Å of monobody atoms, respectively. (E) Epitope mapped by NMR spectroscopy. Red, yellow, and white spheres indicate the Cα atom positions for residues whose NMR signals are strongly affected, weakly affected, and not affected, respectively. (F) A comparison of the backbone conformation of the recognition loops between monobody MBP-74 and wild-type FNfn10 (PDB ID code 1FNF). The BC, DE, and FG loops of the monobody are shown in cyan, yellow, and green, respectively, and those of wild-type FNfn10 are shown in tan. Residue numbers are also shown.

Crystal Structure of the Monobody–Target Complex.

The monobody scaffold (excluding the three recognition loops) and the corresponding part of the wild-type fibronectin type III domain [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1FNF] had a Cα rmsd value of 0.54 Å, indicating that the FNfn10 scaffold is essentially unaffected by the extensive mutations in the loops. The backbone conformations of the BC and FG loops of the monobody, where all mutations are located, are very different from those of their counterparts in the uncomplexed wild-type protein, suggesting their inherent plasticity (Fig. 3F). MBP was in the open form, similar to that of the MBP/β-cyclodextrin (βCD) complex (PDB ID code 1DMB; Cα rmsd = 0.81 Å).

The recognition loops of the monobody segment interact with the sugar-binding cleft of the MBP segment of an adjacent fusion protein (Fig. 3C). Hereafter we will refer to this combination of monobody and MBP as the “binding complex” and the interface between them as the “binding interface.” Following the convention for antibody–antigen complexes, we will refer to the interaction interface of MBP as the epitope and that of the monobody as the paratope.

We confirmed that this binding complex represents the interaction in solution using two independent methods. First, we mapped the monobody-binding epitope of MBP by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy (SI Fig. 6). Monobody binding affected the backbone 1H, 15N, and 13C′ resonances of MBP residues that overlap with the epitope seen in the crystal structure (Fig. 3 D and E). The NMR perturbation results indicate that the monobody binds to a single, dominant epitope on MBP. Note that an epitope mapped by this NMR method is usually twice as large as the actual structural epitope because this method detects residues that are affected by direct and indirect contacts (12). Second, the binding of MBP-74 to MBP was competitively inhibited by βCD that binds to the cleft (data not shown).

Binding Interface.

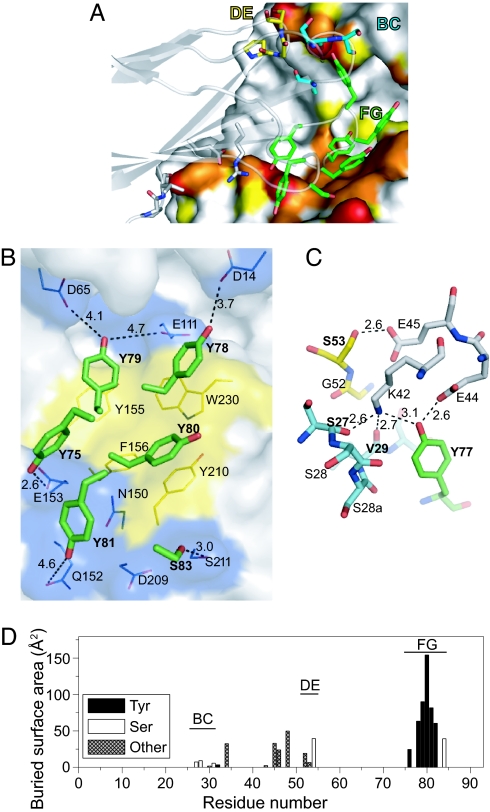

The binding interface buries 749 Å2 of monobody surface and comprises 16 residues of the monobody and 22 residues of MBP (interface residues are defined as those with buried surface area ≥5 Å2) (SI Fig. 7). Although the DE loop contains the wild-type sequence, all three recognition loops are involved in the interaction. Both the epitope and paratope are bisected by a deep unfilled cavity, resulting in two distinct sets of contacts (Figs. 3D and 4A). The monobody FG loop and a part of the scaffold interact with the “bottom” lobe of MBP, and the BC and DE loops together with a single Tyr residue from the FG loop interact with the “top” lobe (Fig. 4A). The contacts made by the monobody scaffold residues are potentially due to lattice packing because the contact residues are mostly polar and charged, and NMR epitope mapping data show little to no chemical shift perturbation in this area (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 4.

The binding interface of the MBP-74 monobody and MBP. (A) The monobody paratope residues are shown as stick models, and the MBP epitope surface is shown in the same manner as in Fig. 3D. The carbon atoms of BC, DE, and FG loop residues of the monobody are in cyan, yellow, and green, respectively. The oxygen and nitrogen atoms are shown in red and blue, respectively. The monobody backbone is also shown as a transparent cartoon model. (B) Interactions between the monobody FG loop residues (stick models) and the MBP bottom lobe epitope (shown as surfaces). The surfaces of aromatic residues are shown in yellow. Potential polar interactions for the hydroxyl oxygen atom of the paratope Tyr residues are shown as dashed lines with their distances. The monobody residues are indicated in bold. (C) The interactions in the top lobe epitope. MBP residues are drawn with carbon atoms in gray. The carbon atoms of BC, DE, and FG loop residues of the monobody are in cyan, yellow, and green, respectively. (D) The buried surface areas of the monobody residues. Only those for the binding complex are shown.

The FG loop residues contribute the bulk of the interface surface (513 Å2) (Fig. 4D) and mediate contact with MBP almost exclusively through the side chain atoms. Of the seven Tyr residues in this loop (Fig. 1A), three interact closely with aromatic residues of MBP (Fig. 4B). They form a central hydrophobic patch that is surrounded by a more polar periphery consisting of the hydroxyl groups of five Tyr residues (Fig. 4B). The remaining Tyr residues do not contribute to this contact: Y82 lies against the backside of the Tyr cluster that forms the binding interface, and Y77 stretches away.

The BC and DE loops together with Y77 interact with three charged residues on the top lobe of MBP (Fig. 4 A and C). This interface nearly completely buries K42, E44, and E45 of MBP to account for 149 Å2 of the monobody interface surface area. Contrary to the FG loop, the majority of the contacts here are mediated by the backbone atoms. The carbonyl groups of S27 and V29 of the BC loop and the hydroxyl group of Y77 form hydrogen bonds with the buried K42 of MBP. In addition, nearby E44 and E45 of MBP form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of Tyr-77 and Ser-53, respectively. These Glu residues may compensate for the burial of K42's ε-amino group.

In addition to the binding interface, each monobody molecule forms a large intrachain contact interface (520 Å) with the MBP molecule to which it is fused, as well as a 214-Å2 contact with a symmetry-related MBP. Together with the binding interface, 28% of the total monobody surface is buried in the crystal structure.

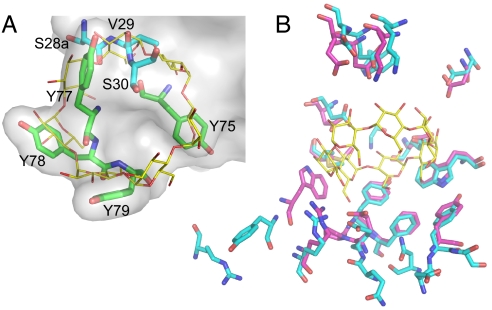

Substrate Mimicry by the Monobody.

A structural comparison of the MBP–monobody complex with MBP complexed with its βCD substrate revealed that the MBP epitopes for βCD and the monobody share 12 residues that have nearly identical conformations in the two structures (Fig. 5B). Many βCD structural elements are closely mimicked by the monobody binding loop structures (Fig. 5A). In particular, the aromatic rings of FG loop Tyr show striking overlap with the sugar rings of βCD, and they use the same hydrophobic contacts. Furthermore, many of the hydroxyl groups of βCD are emulated by the Tyr hydroxyls and backbone carbonyls, which resulted in conservation of a similar hydrogen bonding pattern.

Fig. 5.

Structural mimicry of βCD by the monobody. (A) Superposition of βCD bound to MBP (PDB ID code 1DMB) and the monobody paratope residues. MBP Cα atoms were used to superimpose the two structures. Only residues in the monobody paratope that overlap with βCD are shown. The surface is drawn for the entire monobody. The carbon atoms of βCD are shown in yellow, and those of the monobody are color-coded in the same manner as in Fig. 4A. (B) Comparison of the MBP epitope to βCD (carbon atoms in magenta) with that to the MBP-74 monobody (carbon atoms in cyan).

Dominant Functional Contribution of Tyr Residues in the Paratope.

We then tested whether the loop residues of MBP-74 could be substituted with other amino acids. We constructed two secondary libraries in which either the BC or FG loop was diversified with a mixture of Y, S, F, A, D, and V at each position. We found that all of the residues in the BC loop tolerate extensive mutations (SI Fig. 8A). In contrast, only Y82 and S83 in the FG loop can be replaced with another amino acid (SI Fig. 8C). Y82 can be changed to F but not to S, A, D, or V. The phenolic ring of Y82 packs against the interface Tyr residues and appears to support the paratope structure. S83 was completely replaced with either A or D, suggesting that A and D are preferred over S at this position. These results clearly indicate the essential contributions of most of the FG loop residues.

Discussion

General Effectiveness of the Y/S Binary Interface.

The low-nanomolar affinities of the obtained Y/S monobodies are comparable to those for natural antibodies and to those of the Y/S Fabs of Fellouse et al. (17–1,400 nM) (2). The monobody scaffold presents a smaller number of recognition loops and thus fewer residues that can potentially form a binding interface than the antibody scaffold. Therefore, the versatility of these “minimalist” monobodies strongly suggests universal effectiveness of Y/S binary interfaces in protein interaction.

Tyr side chains and backbone atoms of the monobody closely mimic βCD, MBP's carbohydrate ligand (Fig. 5), showing that the backbone atoms of the recognition loops provide additional chemical diversity. The ability of the Y/S binary interface to mimic not only polypeptides but also another class of biomolecules implies broad utility of this minimalist interface.

We found that all Tyr residues in the FG loop that directly contact with MBP are functionally essential. Our results are distinct from those on a Fab with a 4-aa code interface (13). They found that, although Tyr residues in the paratope are important, they could be substituted with other amino acids without a detrimental effect. We speculate that, with the severely restricted chemical diversity presented on the small monobody scaffold, most of the available chemical groups need to be used for achieving high affinity. Although this notion suggests small probability of finding a high-affinity binder in a Y/S binary library, our results demonstrate that the diversity of our library (≈1010) is sufficiently large for producing binders to protein targets.

Common Features of the Y/S Binary Interface.

The monobody structure represents the second of a protein with a Y/S binary interface. A structural comparison of the Y/S monobody and the Y/S Fab (Fab-YSd1; PDB ID code 1ZA3) reveals both scaffold-specific and common features. The two interfaces have distinct overall shapes (highly convex versus slightly concave) (SI Fig. 9), as manifested in their planarity values (Table 1). Also, the loops that contribute the bulk of the interface form distinct backbone conformations in the two molecules. The monobody FG loop has a hairpin-like backbone structure, whereas complementarity-determining region H3 of Fab-YSd1 takes on a helical conformation.

Table 1.

Properties of the monobody paratope and those of related proteins

| Protein (PDB ID code) | Interface area, Å2 | Polar interface area, % | Planarity | Shape complementarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monobody* | 749 (601) | 44.0 (41.4) | 3.63 (3.39) | 0.66 (0.66) |

| VHH† | 769 ± 146 | 46.6 ± 8.0‡ | 2.59 ± 0.51 | 0.71 ± 0.069 |

| Ankyrin repeat (1SVX) | 611 | 31.6 | 2.08 | 0.74 |

| Fab-YSd1 (1ZA3) | 767 | 48.3 | 2.51 | 0.66 |

Parameters were calculated by using the protein–protein interaction server (21) and the program SC (22), except for five VHHs (1JTT, 1RJC, 1RI8, 1ZVY, and 1ZV5) that were obtained from ref. 14.

*The parameters for the entire paratope and those for the paratope from which the scaffold residues are omitted (in the parentheses) are shown.

†The average and standard deviation for eight VHH structures that bind to a cleft (PDB ID codes 1KXQ, 1KXT, 1SQ2, 1JTT, 1RJC, 1RI8, 1ZVY, and 1ZV5).

‡This excludes information for PDB ID code 1KXQ because of its incompatibility with the protein–protein interaction server.

Despite the conformational differences, the two interfaces bury similar amounts of surface areas and Tyr side chains from a single loop dominate both interfaces (Fig. 4 and SI Fig. 9 A and C). In the monobody, all of the Tyr residues in the paratope are located in the FG loop, and five of them form a contiguous surface. The binding interface is bisected, and the other loops are the primary contributors to the other patch of the interface (Fig. 4). Of eight Tyr residues in the Fab paratope, five from complementarity-determining region H3 form a contiguous surface, and, although the Fab interface as a whole is contiguous, it contains large gaps (SI Fig. 9B). Together, the two structures establish a common mode of Y/S binary interface architecture in which a single major Tyr cluster forms a large patch that is supplemented by other residues.

The higher resolution of the monobody structure (2.35 Å) provides a level of detail for the Y/S interface that was not possible with the lower resolution (3.35 Å) Fab structure. We found that the closest contacts between the interface Tyr residues and MBP are made by the hydroxyl moiety (Fig. 4), with those of five of the six essential Tyr forming polar contacts with MBP residues. It is very likely that such polar contacts make critical contributions to the high levels of binding affinity and specificity that these Y/S binary interfaces can achieve with extremely restricted chemical diversity. Thus, the success of these Y/S binary interfaces can be attributed to the unique properties of Tyr that can form both polar and nonpolar interactions (6) and to the backbone plasticity of the recognition loops that can create distinct surface shapes even with the planer and rigid Tyr phenolic groups.

We note that MBP was the least successful target for the Y/S binary Fabs (2). The Fab clone they obtained had a Kd of >5 μM, ≈100-fold larger than the Kd values for the MBP-binding monobodies (Fig. 1B). We speculate that ligand-binding cleft of MBP is the only binding hot spot against which a high-affinity Y/S binding interface can be made, and the generally flat or concave Fab paratope cannot penetrate into this cleft. These results further emphasize an increased importance that shape complementation has in forming a binding interface when the chemical diversity is severely restricted.

Comparison with Other Natural and Engineered Binding Proteins.

The monobody structure is the first monobody crystal structure in complex with its cognate target. Because monobodies can be categorized as engineered single-domain antibody mimics, we compared the structure with available structures of two classes of related proteins, natural single-domain antibodies and an engineered antibody mimic.

The camelid heavy chain antibodies (VHHs) and monobodies share the β-sandwich architecture, but VHH (≈125 residues) is ≈25% larger than the fibronectin type III domain (≈94 residues). A number of crystal structures of VHHs from the natural immune diversity are available. It has been shown that VHH has a strong preference to binding to a cleft (14). The interface size and polarity of the MBP-74 monobody is similar to the average values for eight cleft-binding VHHs (Table 1). In contrast, the larger planarity index of the monobody indicates that the monobody interface is significantly more curved. This may be because of the smaller size of the monobody scaffold, because a surface patch on a smaller scaffold naturally has a higher degree of curvature than that of a patch of the same area on a larger scaffold. The shape complementarity of the monobody interface, as measured with the sc value, was also significantly smaller than the average value for the VHHs, which may have contributed to the high off-rate between this monobody and its target (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the sc value for Fab-YSd1 was likewise small, suggesting that the severe restriction of amino acid chemical diversity resulted in a poorer fit of the binding interface. This observation also suggests the possibility of enhancing their affinity and specificity by improving the shape complementarity.

Considering that the MBP-binding monobodies target the substrate-binding cleft and VHH also tends to target a functional cleft, one might expect that monobodies may only be able to bind to such a preformed cleft. However, we also obtained high-affinity monobodies to ySUMO and hSUMO4 that are single-domain globular proteins that lack a cleft (Fig. 1B). Thus, Y/S binary monobodies can bind to flatter surfaces, as some VHHs do (15). Further structural analysis is needed to determine how the monobody loops adjust when they bind to a flatter surface.

We also compared the monobody structure with an engineered ankyrin-repeat protein that binds to MBP (16). Its paratope has a high degree of chemical diversity, and it binds to an outer surface of MBP distant from the cleft. It buries a relatively small amount of surface, and the interface is more planar and significantly more hydrophobic than the interfaces of the other proteins analyzed (Table 1). Taken together, these comparisons suggest that interfaces with diverse characteristics can be used for engineering a high-affinity protein–protein interaction interface.

Designed 3D Domain Swapping for Crystallizing Protein Complexes.

An important technological aspect of this work is the successful crystallization of the MBP–monobody fusion protein. This technology overcomes two fundamental difficulties in crystallizing a protein complex. First, it is often difficult to precisely prepare a stoichiometric complex for structural studies. Second, individual components of a protein complex often behave poorly in isolation, leading to low levels of protein production and/or poor solubility. Unexpectedly, the oligomeric form of the monobody/MBP fusion protein underwent rearrangement, and the protein formed infinite rods in the crystal, which appears to have promoted crystallization. Further studies are needed to determine the general applicability of this method and the range of suitable interaction affinity.

Conclusions.

This work demonstrates that a protein-binding interface can be made with minimal chemical diversity presented on a very small protein scaffold. The success of the Y/S monobody library can be attributed to the versatility of Tyr to form different types of nonbonded interactions and the conformational diversity created by the surface loops that compensate for the severely restricted chemical diversity. It is also important to note that, although the Y/S binary library is limited in chemical diversity, it is also devoid of amino acids that may interfere with the formation of a binding interface because of charges or high entropy (1, 4). We anticipate that the Y/S binary-code approach would work well in other molecular scaffolds that can generate significant conformational diversity and that one could engineer even smaller binding proteins using the binary-code interface.

Experimental Procedures

Phage Display Library and Selection.

The “shaved” template was constructed by introducing Ser at residues 3, 25–28, 30, 75–83, and 86 in the FNfn10 gene (9). A synthetic DNA fragment that encodes signal sequence of DsbA (17) was fused to the gene for the template, and the fusion gene was cloned into the phage display vector pAS38 (9). A stabilizing mutation (D7K) was also introduced (18).

A phage-display combinatorial library was constructed by introducing the Y/S binary mixture at each position in the BC, DE, and FG loops using the TMT codon (M = A or C), except for V29, which was kept unchanged. Library construction procedures have previously been described (19).

Library selection, using phage display and yeast surface display techniques, and protein production and characterization methods are described in SI Methods.

Structure Determination of the MBP–Monobody Fusion Protein.

MBP–monobody fusion proteins were constructed by connecting the MBP-74 monobody to the C terminus of MBP. Residues 1–3 of the monobody were replaced with Gly-Ser-Ser to facilitate cloning. In another construct a Gly-Ser-Ser linker was added between the two proteins. Methods for x-ray crystallography and epitope mapping by NMR spectroscopy are described in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Kay and V. Tugarinov for MBP NMR assignments; Drs. I. Dementieva and S. Goldstein for hSUMO4; Drs. S. Sidhu and A. Kossiakoff for stimulating discussions; Dr. J. Horn and V. Cancasci for assistance in SPR measurements; the staff of Northeast Collaborative Access Team (Argonne, IL) for their assistance; and the University of Chicago DNA Sequencing and FACS facilities for expert service. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-GM72688 and U54 GM74946 and by the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center. This work is based on research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beam lines of the Advanced Photon Source, supported by award RR-15301 from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health. Use of the Advanced Photon Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. W-31-109-ENG-38.

Abbreviations

- βCD

β-cyclodextrin

- FNfn10

the 10th fibronectin type III domain of human fibronectin

- hSUMO4

human small ubiquitin-like modifier 4

- ySUMO

yeast small ubiquitin-like modifier

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- PDB

Protein Data Bank.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2OBG).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700149104/DC1.

References

- 1.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fellouse FA, Li B, Compaan DM, Peden AA, Hymowitz SG, Sidhu SS. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fellouse FA, Wiesmann C, Sidhu SS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12467–12472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401786101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogan AA, Thorn KS. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fellouse FA, Barthelemy PA, Kelley RF, Sidhu SS. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mian IS, Bradwell AR, Olson AJ. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:133–151. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90617-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zemlin M, Klinger M, Link J, Zemlin C, Bauer K, Engler JA, Schroeder HW, Jr, Kirkham PM. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:733–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koide A, Abbatiello S, Rothgery L, Koide S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1253–1258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032665299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koide A, Bailey CW, Huang X, Koide S. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1141–1151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CV, Liang WC, Dennis MS, Eigenbrot C, Sidhu SS, Fuh G. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Eisenberg D. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1285–1299. doi: 10.1110/ps.0201402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X, Yang X, Luft B, Koide S. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:61–67. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fellouse FA, Barthelemy PA, Kelley RF, Sidhu SS. J Mol Biol. 2005;357:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Genst E, Silence K, Decanniere K, Conrath K, Loris R, Kinne J, Muyldermans S, Wyns L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505379103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decanniere K, Desmyter A, Lauwereys M, Ghahroudi MA, Muyldermans S, Wyns L. Structure Fold Des. 1999;7:361–370. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binz HK, Amstutz P, Kohl A, Stumpp MT, Briand C, Forrer P, Grutter MG, Pluckthun A. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner D, Forrer P, Stumpp MT, Pluckthun A. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:823–831. doi: 10.1038/nbt1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koide A, Jordan MR, Horner SR, Batori V, Koide S. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10326–10333. doi: 10.1021/bi010916y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koide A, Koide S. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;352:95–109. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-187-8:95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Main AL, Harvey TS, Baron M, Boyd J, Campbell ID. Cell. 1992;71:671–678. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90600-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones S, Thornton JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:946–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.