Abstract

The Nod-like receptor family in man contains proteins that recognize invasive bacteria. Nod1, a member of this family, is activated by specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptides that contain meso-diaminopimelic acid. Plants contain a large family of proteins known as resistance (R) proteins that have common structural features with the Nod-like receptors and are essential for protection against a variety of plant pathogens. Extensive genetic studies have shown that the R protein function is determined by multiple proteins including SGT1, Rar1, and HSP90. Here we show that SGT1 positively regulates Nod1 activation. Depletion of SGT1 with siRNA did not affect stability of Nod1 protein or of downstream signaling molecules but did prevent multiple cellular responses associated with Nod1 activation. In contrast, depletion of the mammalian orthologue of Rar1, Chp1, had no effect on Nod1-dependent cellular activation. Finally, depletion of HSP90 or addition of a pharmacologic inhibitor of HSP90 resulted in loss of Nod1 protein. Thus, we show common regulatory pathways in plant R protein and human Nod1-dependent pathways and provide the basis for understanding the Nod1 pathway.

Keywords: Chp1, HSP90, SIP, Nod2, Nod-like receptors

Multicellular organisms have evolved nonoverlapping defense mechanisms that allow them to respond to attacks by a variety of microbial and viral pathogens. A large body of work has highlighted the critical role of the transmembrane proteins known as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in innate immunity in man and in lower organisms including Drosophila (1). Most recently, a second family of intracellular proteins known as the Nod/NLR/CATERPILLER family has been under intensive study because of their predicted role in pathogen recognition, chronic inflammation, and human diseases (2). These proteins have structural homologies to a large family of resistance (R) proteins found in plants. R proteins play essential roles in plant innate immunity to broad classes of pathogens (3). Interestingly, Drosophila does not have a family of proteins corresponding to the R proteins or the NLRs, and thus the extensive genetic studies of innate immunity in Drosophila have not been informative about the NLR family.

Two members of the NLR family, Nod1 and Nod2, are sensors of intracellular bacteria (2). These proteins recognize distinct substructures of bacterial peptidoglycans found in Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms (4–6). Activation of Nod1 or Nod2 leads to diverse cellular responses that include activation of intracellular signaling pathways, cytokine production, and programmed cell death. Recently, we showed that Nod1-dependent cellular signaling such as cytokine production requires the protein kinases RIP2 and TAK1 (7). Nod1-dependent cell death has different requirements that include a dependence on caspase 8 and RIP2 (7). Although models of Nod1 activation have been proposed, there is little known about other proteins that impact Nod1 activation. In contrast, a number of additional proteins have been linked to R protein pathways of host defense in plants. These proteins include SGT1, Rar1, and HSP90 (3, 8–10).

SGT1 (suppressor of the G2 allele of Skp1) is a highly conserved protein found in yeasts, plants, and mammals (11, 12). SGT1 is devoid of a catalytic domain but contains three distinct protein interaction motifs: the amino-terminal region containing a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR), a central CS domain (shared by CHORD-containing protein and SGT1), and a carboxyl-terminal SGS domain (SGT1-specific). SGT1 is found in both the nucleus and the cytosol. It functions in multiple biological processes through interaction with different multiprotein complexes. For example, in yeast, SGT1 mediates the assembly of the centromere binding factor 3/kinetochore complex through its interaction with Skp1 (13). SGT1 was also recently identified as a component of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex (12). Most importantly, there is a large body of evidence implicating SGT1 in the regulation of resistance to pathogens in plants (11, 14–16). Genetic studies in plants have identified SGT1 as a crucial component for pathogen resistance through regulation of expression levels and activities of some R proteins. This function derives from SGT1 interactions with HSP90 and another protein known as Rar1 (17, 18). Rar1 is a member of the highly conserved CHORD-containing family (CHP). Plant Rar1 contains two highly similar but distinct cysteine- and histidine-rich zinc-binding domains (CHORD I and CHORD II) and associates with SGT1. In plants, some R protein pathways require both SGT1 and Rar1, others require only one of the two. A human orthologue of Rar1 has been identified and named Chp1 (CHORD-containing protein) (19). Chp1 is ubiquitously expressed and also interacts with HSP90 (20). However, the physiological function of Chp1 is unknown. Recently, Nod1 was shown to bind to HSP90, suggesting to us that information derived from studies of plant R protein pathways might reveal new information about pathways involving NLR proteins (21).

In this article we address the involvement of SGT1, Chp1, and HSP90 in Nod1-dependent cell activation. Here we provide multiple lines of evidence showing that SGT1 is a positive regulator of Nod1 activation in epithelial lineage cells. In contrast, cellular responses that occur after activation of the closely related protein, Nod2, are not dependent on SGT1. These results provide previously unrecognized evidence that SGT1, an essential component of some R protein pathways in plants, is required for signaling by Nod1 in human cells. We also show that HSP90 is important for maintaining the content of Nod1 in resting cells. In their totality, these data provide understanding of the Nod1 pathway in mammalian cells and emphasize the value of continuing to draw on information from studies of plant R protein pathways as a means to enhance our understanding of how Nod1 and perhaps other NLR proteins function.

Results

Association of Nod1 with SGT1 and HSP90.

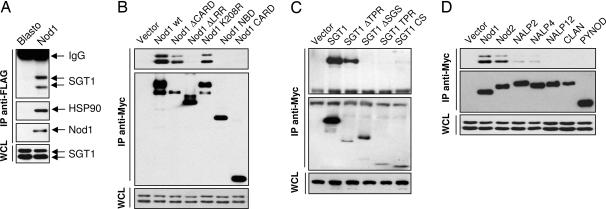

In plants, HSP90 and the cochaperones SGT1 and Chp1 are known to be important for functional R protein responses (11, 17, 18, 22). These studies prompted us to investigate the role of SGT1 in Nod1 and Nod2 signaling pathways. We first asked whether we could detect an interaction between the mammalian homologues of these proteins in epithelial lineage cells. Here we used MCF-7 cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged Nod1 with appropriate control transfectants (7). Lysates from MCF-7 Nod1 cells or from control MCF-7 cells were treated with anti-FLAG antibody, and the resultant immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with anti-SGT1 and anti-HSP90 antibodies. The anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates contained endogenous SGT1 and HSP90 (Fig. 1A). These data indicate that Nod1 is found in a multiprotein complex containing HSP90 and SGT1.

Fig. 1.

Nod1 associates with endogenous SGT1. (A) MCF-7 cells stably expressing empty vector or Nod1-FLAG were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody, and coprecipitated proteins were revealed by immunoblotting using anti-SGT1 or anti-HSP90 antibodies. Expression of Nod1 was detected after stripping of membrane and staining with anti-FLAG antibody. Whole cell lysates (WCL) from both stable transfectants were checked for SGT1 expression. (B) 293 cells were transfected with empty vector or vectors encoding for indicated Nod1 deletion mutants. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and coprecipitated proteins were revealed by immunoblotting using anti-SGT1 antibody. Expression of Nod1 wild type and mutants was detected after stripping of membrane and staining with anti-Myc antibody. WCL were checked for SGT1 expression. (C) 293 cells were cotransfected with Nod1-FLAG and indicated Myc-tagged SGT1 deletion mutants. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and coprecipitated Nod1 protein was revealed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody. Expression of SGT1 wild type and mutants was detected after stripping of membrane and staining with anti-Myc antibody. WCL were checked for Nod1-FLAG expression. (D) 293 cells were transfected with empty vector or vectors encoding for various Myc-tagged NLR proteins. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and coprecipitated proteins were revealed by immunoblotting using anti-SGT1 antibody. Expression of NLR proteins was detected after stripping of membrane and staining with anti-Myc antibody. WCL were checked for SGT1 expression.

To explore the regions of Nod1 that are responsible for interaction with SGT1, we tested a series of Myc-tagged Nod1 deletion mutants. These constructs were transfected in 293 cells, cell lysates were prepared, and interaction with endogenous SGT1 was studied by immunoprecipitation. Nod1, Nod1ΔCARD, and an inactive point mutant of Nod1 (Nod1 K208R) each interacted with endogenous SGT1. In contrast, no interactions were noted when we expressed Nod1ΔLRR, the nucleotide-binding domain, or the CARD domain (Fig. 1B). This interaction was confirmed with the reciprocal experiment, in which SGT1-FLAG coimmunoprecipitated Nod1, Nod1ΔCARD, and Nod1 K208R. A strong interaction was also detected with Nod1 LRR, further supporting the crucial role of this domain in the association with SGT1 [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. We also performed experiments to define the domains of SGT1 involved in these interactions. To identify the domain involved in binding to Nod1, we generated various SGT1 deletion mutants. These mutants were transiently expressed in 293 cells together with FLAG-Nod1. Both the CS and SGS domains were required for association with Nod1 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the absence of the TPR domain did not alter interaction between SGT1 and Nod1.

Finally, we coexpressed a number of NLR family members to determine whether other LRR-containing proteins also interact with endogenous SGT1 (Fig. 1D). We observed that among the series of seven proteins tested, strong interactions of Nod1 and Nod2 were noted. In contrast, very weak interactions with NALP2 and NALP4 could be detected, and we failed to see binding when we expressed other NLRs such as NALP12, CLAN, or PYNOD. Thus, there are unique structural features found in Nod1 and Nod2 that are not generally present in other NLR family members.

Impaired Cytokine Production and Apoptosis After SGT1 Depletion.

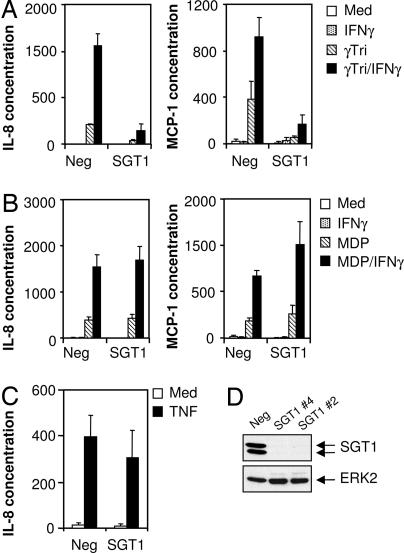

Our previous work showed that addition of low concentrations of cycloheximide enhanced Nod1-dependent cellular activation pathways including those leading to cytokine production and to apoptosis (7). Here we show that the inclusion of IFN-γ enhances the production of cytokines in MCF-7 Nod1 cells treated with the Nod1 activator Ala-γGlu-mesodiaminopimelic acid (γTriDAP), completely eliminating the requirement for added cycloheximide (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, we also found that IFN-γ enhanced cellular responses when we activated the Nod2 pathway with muramyl dipeptide (MDP) (Fig. 2B). Thus, based on these data, we have included IFN-γ in experiments described here. Next we asked whether there is a functional role for SGT1 in Nod1- or Nod2-dependent cellular responses. To address this question, we obtained two siRNA oligonucleotides that specifically targeted human SGT1 mRNA. Both siRNAs almost completely abolished SGT1 protein expression in MCF-7 Nod1 cells, whereas a nondepleting control siRNA had no effect (Fig. 2D). Treatment with the depleting siRNA substantially reduced γTriDAP-induced IL-8 and MCP-1 release in MCF-7 Nod1 cells (Fig. 2A). We also depleted SGT1 in MCF-7 Nod2 cells; interestingly, absence of SGT1 did not impair Nod2 signaling (Fig. 2B). To further demonstrate the specificity of the role of SGT1 on the Nod1 pathway, we showed that absence of SGT1 did not reduce TNFα-induced IL-8 release (Fig. 2C). Similar observations were made in HeLa cells in which SGT1 depletion blunted Nod1- but not TNFα-induced cytokine release (data not shown). These findings support the contention that SGT1 is essential for a functional Nod1 signaling pathway but does not appear to be required for the same responses induced by Nod2 or TNFα pathway activation.

Fig. 2.

Impaired cytokine production in SGT1 depleted cells. (A and B) MCF-7 Nod1 (A) and MCF-7 Nod2 (B) cells were transfected with control siRNA or SGT1 no. 4 siRNA. Cells were left untreated or treated with γTriDAP or MDP (20 μg/ml each) in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (1,000 units/ml) for 24 h. Cell supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-8 (Left) and MCP-1 (Right) production. (C) MCF-7 Nod1 cells were transfected with control or SGT1 no. 4 siRNA. Cells were treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cell supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-8 production. (D) Depletion of endogenous SGT1 protein using SGT1 no. 2 and no. 4 siRNAs was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-SGT1 antibody. The same blot was reprobed for anti-ERK2, indicating equal protein loading. Med, medium; Neg, negative.

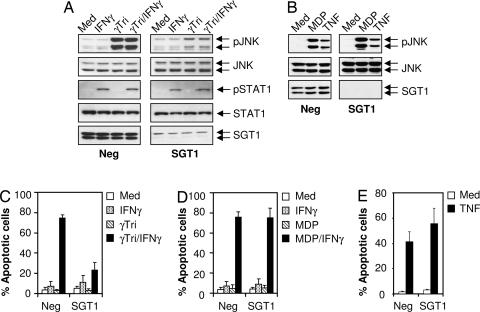

Next, we asked whether SGT1 depletion reduces events preceding cytokine expression such as MAPK phosphorylation. We observed that depletion of SGT1 resulted in inhibition of γTriDAP-induced JNK phosphorylation in MCF-7 Nod1 cells (Fig. 3A). To demonstrate the specificity of SGT1 on the Nod1 pathway, we show that IFN-γ-induced STAT1 phosphorylation is identical in control and SGT1 depleted cells, supporting our contention that SGT1 depletion is selective for the Nod1 pathway. We also determined that JNK phosphorylation induced by treating cells with IFN-γ and γTriDAP depends on the presence of SGT1. A similar experiment was conducted in MCF-7 Nod2 cells stimulated with MDP. Silencing of SGT1 did not affect MDP-induced JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 3B). Similarly, JNK phosphorylation induced by TNFα was identical in control and SGT1-depleted cells. We also evaluated the effect of SGT1 depletion on apoptosis induced by Nod1 activation in the presence of IFN-γ using MCF7-Nod1 cells (Fig. 3C). Under these experimental conditions we observed that SGT1 is required for this cell death pathway. Surprisingly, we also determined that MCF-7 Nod2 cells treated with the MDP in the presence of IFN-γ undergo substantial apoptosis, with 80% of the cells dying within 24 h (Fig. 3D). However, in contrast to the effects of SGT1 depletion on Nod1-induced cell death, Nod2- as well as TNFα-induced apoptosis was identical in both cell groups (Fig. 3 D and E).

Fig. 3.

SGT1 is a critical component of Nod1 signaling pathways. (A) MCF7 Nod1 cells were transfected with control siRNA or SGT1 no. 4 siRNA. Cells were stimulated with γTriDAP (20 μg/ml), IFN-γ (1,000 units/ml), or both for 2 h. Cell lysates were prepared, and JNK and STAT1 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-phospho JNK and anti-phospho STAT1 antibodies. The same blots were reprobed for anti-JNK and anti-STAT1, indicating equal protein loading. Depletion of endogenous SGT1 protein was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-SGT1 antibody (bottommost panels). (B) MCF7 Nod2 cells were transfected with control siRNA or SGT1 no. 4 siRNA. Cells were stimulated with MDP (20 μg/ml) for 2 h or TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were prepared, and JNK phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-phospho JNK antibody. The same blots were reprobed for anti-JNK, indicating equal protein loading. Depletion of endogenous SGT1 protein was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-SGT1 antibody (Bottom). (C–E) MCF7 Nod1 (C and E) and MCF-7 Nod2 (D) cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting SGT1. Cells were left untreated or treated with γTriDAP or MDP (20 μg/ml each) in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (1,000 units/ml) for 36 h or TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 18 h. Cells were incubated with propidium iodide, and apoptotic cell death was measured by flow cytometry. Med, medium; Neg, negative.

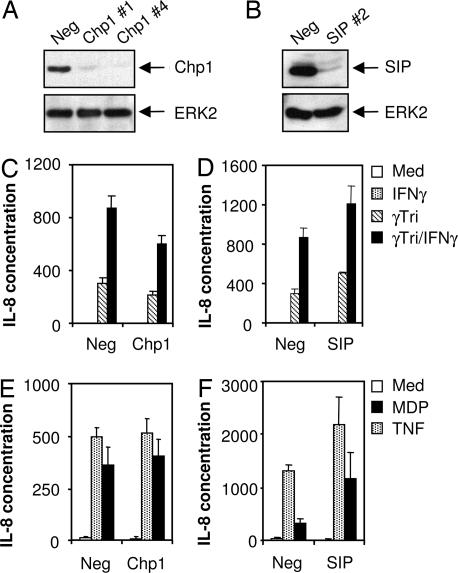

Chp1 and SIP Do Not Participate in the Active Nod1 Complex.

The plant protein Rar1 has been shown to associate with SGT1 and HSP90 and is required for the function of some R proteins (14, 18). A mammalian orthologue of RAR1, Chp1, has been identified but its function is unknown (19). We next asked whether we could establish a role for Chp1 in Nod1-dependent signaling pathways. Silencing of Chp1 expression in MCF-7 cells did not affect IL-8 production in response to γTriDAP or MDP (Fig. 4 C and E). Depletion of Chp1 was confirmed by immunoblotting using anti-Chp1 antibody (Fig. 4A). These data are in marked contrast to the effects we observed when we depleted SGT1. We also examined a third protein known as SIP (Siah-interacting protein). SIP was chosen because it is structurally and functionally related to SGT1. For example, it has been shown that the carboxyl-terminal region of SIP complements defects in yeast sgt1 mutants (23). More recently, SIP has also been implicated in pathogen resistance in plants (24). We used siRNA depletion to eliminate SIP (Fig. 4B) and examined the consequences with respect to either Nod1 or Nod2 signaling. We observed a slight but consistent enhancement of IL-8 release in response to γTriDAP and MDP exposure (Fig. 4 D and F). SIP depletion also increased TNFα-induced IL-8 secretion, suggesting that SIP might act as a negative modulator of cytokine production. We next investigated whether SIP and Chp1 could physically interact with Nod1 by coimmunoprecipitation assays. We could not detect SIP or Chp1 in Nod1 immunoprecipitates (SI Fig. 7). In their totality, these data indicate that neither Chp1 nor SIP is required for signaling via Nod1 or Nod2 pathways and further emphasize the specificity for SGT1 in Nod1 signaling pathways.

Fig. 4.

Chp1 and SIP do not modulate Nod1 activities. (A and B) MCF-7 Nod1 were transfected with control siRNA or specific siRNAs targeting Chp1 or SIP. Depletion of endogenous Chp1 and SIP proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting using anti-Chp1 and anti-SIP antibodies. The same blots were reprobed for anti-ERK2, indicating equal protein loading. (C and D) MCF-7 Nod1 cells were transfected with control, Chp1 no. 4 (B), or SIP no. 2 (C) siRNAs. Cells were left untreated or treated with γTriDAP (20 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (1,000 units/ml) for 24 h. Cell supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-8 production. (E and F) MCF-7 Nod2 cells were transfected with control, Chp1 no. 4 (E), or SIP no. 2 (F) siRNAs. Cells were left untreated or treated with MDP (20 μg/ml) or TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cell supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-8 production. Med, medium; Neg, negative.

HSP90 but Not SGT1 Controls Nod1 Stability.

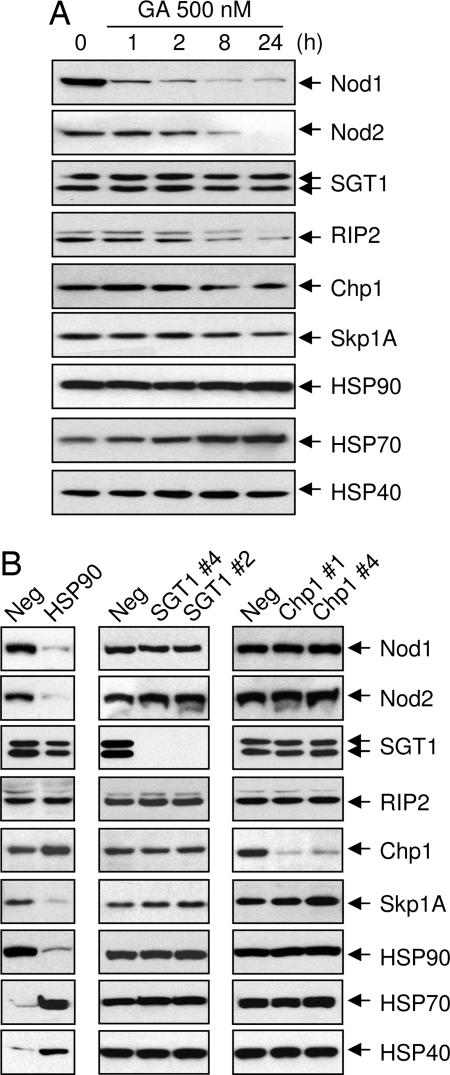

A previous report showed that treatment of cells expressing Nod1 with geldanamycin (GA) reduced expression of Nod1 presumably through inhibition of the ATPase activity of HSP90 (21). Here we showed that GA used at low concentrations (250 nM) essentially eliminated Nod1 protein expression in MCF-7 Nod1 cells after 1 h of exposure (Fig. 5A). To rule out a possible effect of GA on Nod1 transcript levels, we measured Nod1 mRNA by real-time quantitative PCR. We observed that Nod1 mRNA remained constant, suggesting that GA destabilizes Nod1 protein levels (SI Fig. 8). Levels of SGT1, Chp1, HSP90, and HSP40 proteins remained essentially unchanged. As expected, the presence of GA increased the basal levels of HSP70 protein (25). GA treatment also destabilized RIP2 and Skp1A. The latter is known to interact with SGT1 in plants and yeast (11, 26). Similarly, we observed that Nod1 protein was consistently reduced in total lysates from HSP90-depleted cells (Fig. 5B). To confirm these results, we performed the same experiments using a different set of siRNA targeting HSP90α and HSP90β and obtained similar results (SI Fig. 9). Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of HSP90 also destabilized Nod2. Interestingly, knocking down HSP90 expression increased protein levels of HSP70 and HSP40. In contrast, absence of SGT1 or Chp1 did not affect Nod1 protein levels. To test whether the defect in Nod1 responses in SGT1-depleted cells is linked to protein degradation, we studied the stability of various components linked to Nod1 signaling through our work or the work of others. We observed that SGT1 depletion did not alter the protein levels of RIP2, Chp1, Skp1A, HSP90, HSP70, and HSP40. Similarly, knocking down Chp1 did not change protein levels of these various signaling components.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of steady-state protein levels of Nod1 and other proteins. (A) Inhibition of HSP90 promotes degradation of Nod1. MCF-7 Nod1 or MCF-7 Nod2 cells were treated with GA (250 nM) for indicated times. Cells were lysed, and Nod1 or Nod2 expression was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Myc antibody. The same blots were stripped and reprobed with indicated antibodies. (B) MCF-7 Nod1 or MCF-7 Nod2 cells were transfected with control siRNA or specific siRNAs targeting HSP90, SGT1, or Chp1. Depletion of the endogenous protein targeted by the siRNA was confirmed by Western blotting using indicated antibodies. The same blots were stripped and reprobed with specific antibodies noted in the figure. Neg, negative.

Discussion

Here we provide multiple lines of evidence showing that SGT1, a highly conserved and ubiquitous protein in eukaryotes, plays an essential role in signaling pathways linked to activation of Nod1 in epithelial lineage cells. SGT1 is an adaptor protein with multiple biological functions. It was first identified as an essential component of cell cycle control in yeast (12). Of relevance to the studies presented here is that it has also been shown to be important for plant immune defense mechanisms that use R protein pathways (11, 14). Possible relationships between members of the mammalian NLR family and plant R proteins have been suggested based on domain homologies. Now we provide evidence derived from functional studies in human cells suggesting common regulatory pathways. Our data links SGT1 to the Nod1 activation pathway as an essential component that is likely to act early in the events leading to Nod1 activation. Interestingly, we failed to detect a dependence on SGT1 when we examined the closely related NLR family member, Nod2. This finding suggests that these two closely related proteins have evolved unique regulatory mechanisms for the very earliest steps in their respective pathways because both require RIP2 for their downstream effects. An alternative explanation may be that the amounts of SGT1 needed to support Nod2 signaling are far lower than needed for Nod1. Additional biochemical studies are needed to address this possibility. However, we wish to note that this difference between these closely related proteins, Nod1 and Nod2, is consistent with results from studies of host defense in plants in which multiple lines of evidence show SGT1-dependent and -independent R protein responses (11, 15, 27).

Nod1 and SGT1 most likely exist in a multiprotein complex that includes HSP90. HSP90 has also been linked to R protein function in plants (17, 22, 28). Here we used immunoprecipitation to show that in cells expressing Nod1, endogenous HSP90 and SGT1 are coprecipitated. Structure-function studies demonstrate that Nod1 requires the presence of its LRR domain to be found in a complex that also contains SGT1 and HSP90. SGT1 requires its CS and SGS domains. Additional binding studies performed in cell-free systems are required to determine the details of the interactions we observed in cells. Interestingly, immunoprecipitation studies also revealed the presence of a complex of Nod2 with SGT1 and HSP90. However, depletion of SGT1 did not affect any of the cellular responses we measured after Nod2 activation. Whether the interaction of Nod2 with SGT1 is linked to functions of Nod2 not studied here remains to be determined. Nonetheless, it is important to note that we failed to show strong association of other NLR family members such as other LRR-containing proteins with SGT1 despite the presence of structurally related nucleotide-binding domain and LRR domains in each.

Additional data link HSP90 and the Nod1 pathway. Silencing of HSP90 or pharmacological inhibition with GA resulted in a significant reduction of Nod1 protein levels, suggesting that HSP90 plays a key role in stabilizing Nod1, thereby protecting it from degradation. In contrast, silencing of SGT1 did not alter steady-state levels of Nod1 protein. Unlike its suggested role in plants, SGT1 does not appear to be directly linked to regulation of Nod1 levels. The mechanism whereby SGT1 functions in the Nod1 pathway is not clear, and at present, we can only speculate on possible mechanisms. Perhaps binding of SGT1 to the Nod1 complex maintains Nod1 in a signal-competent conformation that allows detection of the Nod1 ligand. Thus, SGT1 may play the role of a coreceptor. Another possible mechanism is that SGT1 is important for proper localization of Nod1 in the cell. It is clear that SGT1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and may help in trafficking of Nod1. The fact that Nod2 was also found in a complex with SGT1 suggests that the interaction between SGT1 and Nod1 may not be required for signaling, rather, SGT1's effect may be indirect by modifying a specific signaling component of Nod1. SGT1 interacts with Rar1, an essential component of resistance conferred by many R genes in plants. SGT1 and Rar1 play distinct roles in innate immunity in plants. Here, we were unable to show a role for the mammalian homologues of Rar1 and Chp1 in the control of Nod1 function.

We recently reported that Nod1 interacts with the COP9 complex and that the CSN6 subunit of the COP9 complex is cleaved as a result of Nod1 activation (29). Thus, we provide a second link between Nod1 and plant R protein pathways. Association of Nod1 with SGT1 and the COP9 complex suggests that SGT1 might play some role in ubiquitination of regulatory proteins. SGT1 is known to play a role in protein degradation through association with the SCF complex through the Skp1 subunit (12). Other studies have also shown that murine SGT1 is associated with the SCFskp2 complex (30). Thus, one possible role of SGT1 could be to target resistance-regulating proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome via specific SCF complexes. In this hypothesis, the target protein would be a negative regulator of immune responses. The target genes of the SCF complex are still unknown. Interestingly, the plant defense-related gene RPM1 is rapidly degraded after RPM1-triggered signaling (31). These studies led to the hypothesis that the COP9 signalosome regulates the SCF complex to promote ubiquitination of unidentified targets during the R gene response. Our observations that Nod1 associates with the COP9 complex as well as SGT1 are further strengthened by the fact that SGT1 and Rar1 have been shown to interact cooperatively with some subunits of the COP9 signalosome in plants (11, 14, 32). Silencing of either one of these two genes renders the plants more susceptible to specific pathogens.

Altogether, the data provided here and our recently published work (29) suggest that SGT1 and the COP9 complex may be key regulators in the R gene-triggered signaling pathway in plants. Future studies should draw from the extensive literature describing R protein-dependent innate immunity in plants to better understand the NLR pathways, and especially those dependent on Nod1 and Nod2 in man.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Human breast cancer cells MCF-7 and HEK-293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin.

Reagents.

Anti-HSP90, anti-HSP70, anti-HSP40, anti-phospho JNK (Thr-183/Tyr-185), anti-JNK, anti-phospho STAT1 (Tyr-701), and anti-STAT1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). M2 anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit anti-Myc antibody was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-Myc 9E10, anti-ERK2, and anti-Chp1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-RIP2 was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Anti-SIP antibody was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Anti-SGT1 was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-Skp1A was from BioLegends (San Diego, CA). Protein A-Sepharose was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Human recombinant TNFα was purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). MDP was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). γTriDAP (Ala-γGlu-mesoDAP) was chemically synthesized by Anaspec (San Jose, CA).

Mammalian Expression Constructs and Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Human Nod1, Nod2, Nod1 ΔCARD, Nod1 ΔLRR, Nod1 LRR, Nod1 nucleotide-binding domain, Nod1 K208R, and Nod1 CARD were described (7). ORFs of the SGT1 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pcDNA4-myc vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Myc-SGT1 ΔTPR, SGT1 ΔSGS, SGT1 CS, and SGT1 TPR were generated by deletion and cloned into the pcDNA4/Myc/His plasmid. NALP2, NALP4, NALP12, and PYNOD were amplified by PCR and cloned into pcDNA4-myc vector (Invitrogen). Myc-CLAN was obtained from John Reed (Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA). Nucleotide sequences were all confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Retroviral Transfections.

MCF-7 cells were stably transfected with Nod1 and Nod2 as described (33). Briefly, amphotropic 293 cells were transfected with pMSCV vector encoding for Nod1 and Nod2 in 10-cm petri dishes by using Lipofectamine/Reagent Plus (Invitrogen). Target cells were infected the next day with 293 cells supernatants containing recombinant retroviral particles in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma). Cells were selected with 10 μg/ml blasticidin S (Calbiochem). Expression of Nod1 and Nod2 was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Preparation of Cell Lysates.

Cells were washed and lysed in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 14 μM pepstatin A, 100 μM leupeptin, 3 mM benzamidine, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, 100 units/ml aprotinin, and 100 mM sodium fluoride. After incubation for 30 min on ice, cell lysates were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatants were recovered.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis.

Cell lysates were precleared once for 30 min at 4°C with 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads and mixed with 1 μg of M2 mAb for 3 h at 4°C under constant agitation. Immune complexes were allowed to bind to 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads overnight, and beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, resuspended in 30 μl of Laemmli buffer, and boiled for 7 min. Immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS/PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Filters were blocked with 3% BSA in blocking buffer (TBS: 50 mM Tris·Cl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with anti-FLAG, anti-HA, or anti-Myc antibody for 2 h and with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at ambient temperature. Specific bands were revealed by using the ECL Plus system (Amersham).

Cell Viability Assays.

Cells were plated at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates and stimulated as indicated for 36 h. Cell supernatants were collected and pooled with adherent cells that were detached with trypsin-EDTA. Cells were washed twice in FACS buffer (PBS containing 1% FCS and 0.1% NaN3) and resuspended in propidium iodide-containing FACS buffer (4 μg/ml). The extent of cell death was analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

IL-8 and MCP-1 ELISA.

Concentration of IL-8 and MCP-1 in the cell supernatants was measured by ELISA by using 96-well Immunlon plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, VA). IL-8 ELISA was performed by using the mAb MAB208 for capture and a biotinylated rabbit anti-human IL-8 Ab (R & D Systems) followed by streptavidin HRP for detection. MCP-1 ELISA was performed by using mAb MAB679 for capture and a biotinylated rabbit anti-human MCP-1 Ab (R & D Systems). ELISA was developed by using o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma) as a substrate, and OD was determined at a wavelength of 490 nm by using a Spectramax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All values were interpolated from a semilog fit of a curve generated from IL-8 standards.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Assays.

The following siRNAs used in this study were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA): SGT1 (no. 2 and no. 4), CHP1 (no. 7 and no. 11), and SIP (no. 2). HSP90 siRNA was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. MCF-7 cells were transfected with 5-nM double-stranded siRNA by using HiPerfect transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were subjected to various assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI 15136 and U54 AI 54523 and Novartis Grant SFP 1568 (to R.U.).

Abbreviations

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- R

resistance

- GA

geldanamycin

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- NLR

Nod-like receptor

- γTriDAP

Ala-γGlu-mesodiaminopimelic acid.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0610926104/DC1.

References

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ting JP, Davis BK. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;23:387–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin GB, Bogdanove AJ, Sessa G. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:23–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.135035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jehanno M, Viala J, Tedin K, Taha MK, Labigne A, Zahringer U, et al. Science. 2003;300:1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamaillard M, Hashimoto M, Horie Y, Masumoto J, Qiu S, Saab L, Ogura Y, Kawasaki A, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, et al. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:702–707. doi: 10.1038/ni945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva Correia J, Miranda Y, Leonard N, Hsu J, Ulevitch RJ. Cell Death Differ. 2006;14:830–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt BF, III, Hubert DA, Dangl JL. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones JD, Dangl JL. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin MJ, Muskett P, Kahn K, Feys BJ, Jones JD, Parker JE. Science. 2002;295:2077–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.1067747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitagawa K, Skowyra D, Elledge SJ, Harper JW, Hieter P. Mol Cell. 1999;4:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steensgaard P, Garre M, Muradore I, Transidico P, Nigg EA, Kitagawa K, Earnshaw WC, Faretta M, Musacchio A. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:626–631. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azevedo C, Sadanandom A, Kitagawa K, Freialdenhoven A, Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P. Science. 2002;295:2073–2076. doi: 10.1126/science.1067554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peart JR, Lu R, Sadanandom A, Malcuit I, Moffett P, Brice DC, Schauser L, Jaggard DA, Xiao S, Coleman MJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10865–10869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152330599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azevedo C, Betsuyaku S, Peart J, Takahashi A, Noel L, Sadanandom A, Casais C, Parker J, Shirasu K. EMBO J. 2006;25:2007–2016. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubert DA, Tornero P, Belkhadir Y, Krishna P, Takahashi A, Shirasu K, Dangl JL. EMBO J. 2003;22:5679–5689. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi A, Casais C, Ichimura K, Shirasu K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11777–11782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033934100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brancaccio M, Menini N, Bongioanni D, Ferretti R, De Acetis M, Silengo L, Tarone G. FEBS Lett. 2003;551:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Luo S, Jiang H, Li H. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn JS. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4513–4519. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu R, Malcuit I, Moffett P, Ruiz MT, Peart J, Wu AJ, Rathjen JP, Bendahmane A, Day L, Baulcombe DC. EMBO J. 2003;22:5690–5699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuzawa SI, Reed JC. Mol Cell. 2001;7:915–926. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YS, Ham BK, Paek KH, Park CM, Chua NH. Mol Cells. 2006;21:389–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demidenko ZN, Vivo C, Halicka HD, Li CJ, Bhalla K, Broude EV, Blagosklonny MV. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1434–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingelbach LB, Kaplan KB. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8938–8950. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8938-8950.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tor M, Gordon P, Cuzick A, Eulgem T, Sinapidou E, Mert-Turk F, Can C, Dangl JL, Holub EB. Plant Cell. 2002;14:993–1003. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Burch-Smith T, Schiff M, Feng S, Dinesh-Kumar SP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2101–2108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Silva Correia J, Miranda Y, Ulevitch RJ. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyapina S, Cope G, Shevchenko A, Serino G, Tsuge T, Zhou C, Wolf DA, Wei N, Shevchenko A, Deshaies RJ. Science. 2001;292:1382–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1059780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyes DC, Nam J, Dangl JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15849–15854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Schiff M, Serino G, Deng XW, Dinesh-Kumar SP. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1483–1496. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Silva Correia J, Miranda Y, Austin-Brown N, Hsu J, Mathison J, Xiang R, Zhou H, Li Q, Han J, Ulevitch RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1840–1845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509228103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.