Abstract

Leptomeningeal metastases are a serious neurological complication in cancer patients and associated with a dismal prognosis. Tumor cells that enter the subarachnoid space adhere to the leptomeninges and form tumor deposits. It is largely unknown which adhesion molecules mediate tumor cell adhesion to leptomeninges. We studied the role of integrin expression and activation in the progression of leptomeningeal metastases. For this study, we used a mouse acute lymphocytic leukemic cell line that was grown in suspension (L1210-S cell line) to develop an adherent L1210 cell line (L1210-A) by selectively culturing the few adherent cells in the cell culture. β1, β2, and β3 integrins were in a constitutively high active state on L1210-A cells and in a low, but inducible, active state on L1210-S cells. Expression levels of these integrins were comparable in the two cell lines. Static adhesion levels of L1210-A cells on a leptomeningeal cell layer were significantly higher than those of L1210-S cells. All mice that were injected intrathecally with L1210-A cells died rapidly of leptomeningeal leukemia. In contrast, 45% long-term survival was seen after intrathecal injection of mice with L1210-S cells. Our data indicate that constitutive integrin activation on leukemic cells promotes progression of leptomeningeal leukemia by increased tumor cell adhesion to the leptomeninges. We argue that an aberrantly regulated inside-out signaling pathway underlies constitutive integrin activation on the adherent leukemic cell population.

Keywords: adhesion, integrin activation, L1210, leptomeningeal metastases, mouse

Cancer cells can invade the subarachnoid space filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)4 and seed to the leptomeninges, a complication known as leptomeningeal metastases (LM). Any cancer can metastasize to the leptomeninges, but the most common cancer cell types are leukemia, lymphoma, breast cancer, small cell lung cancer, and melanoma (Bleyer and Byrne, 1988; DeAngelis, 1998). Nowadays, LM occurs in up to 8% of patients with solid tumors, and its incidence is increasing: 5% to 15% of patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia and 5% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma develop LM (Bleyer and Byrne, 1988; Colocci et al., 2004). The overall prognosis for patients with LM derived from solid tumors is poor. Untreated patients die within six to eight weeks of their diagnosis (Olson et al., 1974; Rosen et al., 1982), whereas aggressive chemotherapy and radiotherapy increase median survival to four to six months (Grant et al., 1994). The median duration of meningeal remission in patients with leptomeningeal leukemia or lymphoma is approximately two years, and long-term remission can be achieved in 35% of the patients (Balis et al., 1985; Frick et al., 1984). Pathophysiologically, tumor cells can gain access to the subarachnoid space in several ways: hematogenous dissemination, direct extension from bony or parenchymal metastases, perineural migration, or iatrogenic seeding of the meninges during surgical extirpation of brain metastases (Kokkoris, 1983; van der Ree et al., 1999). Once malignant cells enter the subarachnoid space, the CSF flow deposits them to distant sites within the neuraxis. The most common sites of tumor deposition are the basal cisterns and the cauda equina, possibly because gravity and sluggish CSF flow promote adhesion of tumor cells to these sites. Both autopsy of LM patients and animal models of LM show that tumor cells adhere to the leptomeninges and form tumor cell layers or nodules (Reijneveld et al., 1999). However, the role of tumor cell adhesion to the leptomeninges in LM and its mediating adhesion molecules are largely unknown.

Integrins have been identified as principal mediators of tumor cell intravasation, arrest in the blood vessel, extravasation, and infiltration in the target tissue (Ruoslahti, 1999). Integrins comprise a family of at least 24 transmembrane adhesion receptors composed of noncovalently linked α and β subunits, which interact with cellular adhesion molecules (e.g., intercellular adhesion molecule-1 [ICAM-1] and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 [VCAM-1]) or extracellular matrix proteins like collagen, fibronectin, and vitronectin (Hynes, 1992). Integrins are known to exist in distinct activation states, being regulated by inside-out signaling pathways: Extracellular stimuli (e.g., chemokines) induce intracellular signal transduction pathways that subsequently activate integrins (Hynes, 1992; Schwartz et al., 1995). An increase in activation state is determined by two processes: a change in conformation of the integrin (affinity) and/or clustering of integrins on the cell membrane (avidity). Both integrin expression and activation on tumor cells have been linked to tumor progression (Chan et al., 1991; Felding-Habermann et al., 2001; Gosslar et al., 1996). In LM, in vitro studies pointed out a role for integrins in tumor cell adhesion to the leptomeninges. Giese et al. (1998) showed that static adhesion of glioma cells to human arachnoidea could be blocked by antibodies against α2, α3, and β1 integrin subunits. We demonstrated that the interaction of α4β1 integrin on tumor cells and VCAM-1 on leptomeningeal cells mediates initial melanoma cell tethering to the leptomeninges under flow conditions (Brandsma et al., 2002).

To study the role of integrin expression and activation on tumor cells in LM in vivo, we used a mouse acute lymphocytic leukemic suspension cell line (L1210) and generated a derivative, adherent leukemic cell line. Using this model, we show that constitutive integrin activation on leukemic cells contributes to increased in vitro leukemic cell adhesion to the leptomeninges and rapid progression of leptomeningeal leukemia in vivo. Our findings point to an abberantly regulated integrin inside-out signaling pathway in tumor cells as a mechanism of LM progression.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Peptides

Purified rat monoclonal IgGs against mouse L-selectin (CD62L, clone MEL-14), mouse VCAM-1 (CD106, clone 429 [MVCAM.A]), mouse integrin β1 chain (CD29, clone 9EG7; fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis), mouse integrin β1 chain (CD29, clone Ha2/5; static adhesion assays), mouse integrin β2 chain (CD18, clone GAME-46), mouse CD44 (clone KM114), and mouse integrin αv chain (CD51, clone RMV7) were all purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Purified rat monoclonal IgG against mouse αIIb chain (CD41, clone MWReg30) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Purified hamster monoclonal IgGs against mouse ICAM-1 (CD54, clone 3E2) and mouse integrin β3 chain (CD61, clone 2C9.G2) and purified fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mouse anti-rat IgG2a (clone G28-5) and anti-hamster and anti-rat IgG1/2b (clone G70-204 and G94-56) were also obtained from Pharmingen. R-phycoerythrin-conjugated goat F(ab')2 antihamster IgG (H + L) mouse/rat adsorbed second-step reagent was obtained from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc. (Birmingham, Ala.). Antibody concentrations were used as recommended by the manufacturer. Vitronectin was purified according to the method described by Yatohgo et al. (1988). Fibronectin was obtained from Harbor Bio-Products (Norwood, Mass.). Collagen type I was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Recombinant mouse ICAM-1 Fc chimera was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.).

Reagents

Tissue culture supplies (culture media, antibiotics, and trypsin) were obtained from Gibco Biocult (Grand Island, N.Y.). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was purchased from Riedel de Haen (Seelze, Germany). Ethylene glycol-bis tetraacetic acid (EGTA) was and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were obtained from Sigma. Magnesium (II) chloride and manganese (II) chloride hexahydrate were obtained from Merck Biosciences (Bad Soden, Germany).

Mouse L1210 Leukemia Cells

The L1210 mouse lymphocytic leukemia cell line was obtained from the Netherlands Cancer Institute (Amsterdam). As the majority of cells are grown in suspension, this leukemic cell line is called L1210-S (suspension) cell line. We developed an adherent leukemic cell line—named the L1210-A (adherent) cell line (see Results)—by selectively culturing the few adherent cells from the L1210-S line. Both the L1210-S and the L1210-A cell lines were cultured in noncoated flasks in RPMI, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin–l-glutamine (PSG), and 60 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2–95% air at 37°C. L1210-A cells were treated with 10 mM EDTA (pH = 7.5) for 5 min, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and resuspended in the culture medium for cell passaging. The L1210-S cell line was maintained as a suspension culture.

Mouse Leptomeningeal Cells

Primary cultures of mouse leptomeningeal cells were obtained as described previously (Brandsma et al., 2002). Briefly, leptomeninges were dissected from the cortical surface of two-day-old neonatal DBA/2 cortex and treated with 0.25% trypsin for 30 min at 37°C. After trypsin was neutralized, cells were centrifuged (1250 rpm, 5 min, room temperature), resuspended, and plated on poly-l-lysine-coated plates. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing sodium pyruvate and nonessential amino acids (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% PSG, and 0.1% amphotericin. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2–95% air at 37°C and passaged two or three times before use.

Cerebrospinal Fluid

We obtained fresh CSF samples from a single patient with a normal pressure hydrocephalus who had CSF drained via an external lumbar drain (Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Utrecht). Cell count, protein, and glucose levels were within normal limits in these CSF samples.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence flow cytometry was used to measure expression levels of surface adhesion molecules. L1210 cells were treated with 10 mM EDTA (pH 7.5; 5 min), centrifuged, and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4ºC. Cells were resuspended in PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (4°C) and distributed in a concentration of 1–2 × 105 cells/sample in a 96-well plate. They were centrifuged (1250 rpm, 3 min, 4°C) and incubated in 35 μl of appropriately diluted antibody in PBS-1% BSA (60 min, 4°C). Subsequently, cells were washed three times in PBS-1% BSA and incubated for another 30 min in 35 μl of the appropriately diluted, FITC-labeled, second-step antibody (4°C). After washing twice with PBS-1% BSA, stained cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). The mean fluorescence intensity was measured for each sample. Samples that were first incubated with isotype control antibodies and subsequently with FITC-labeled antibodies served as negative controls.

Static Adhesion Assays

For in vitro adhesion assays on matrix proteins, mouse ICAM-1, or leptomeningeal cells, L1210-A and L1210-S cells were washed with PBS, treated with 10 mM EDTA (pH 7.5, 5 min), and washed with PBS again. Cells were resuspended in DMEM without phenol red and sodium pyruvate (Gibco Biocult) and labeled fluorescently by incubation with 5 μM calcein (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged (1250 rpm, 5 min, room temperature) after labeling, washed two times with PBS, and resuspended in DMEM without phenol red and sodium pyruvate. Adhesion assays were performed in triplicate by administering 5 × 105 L1210 cells (>95% viability) per well in a 96-well plate coated with matrix proteins or recombinant mouse ICAM-1. Coating with matrix proteins (vitronectin, 10 μg/ml; collagen, 5 μg/ml) or recombinant mouse ICAM-1 (5 μg/ml) was performed overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, wells were incubated with 2.5% BSA-PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Noncoated wells that were incubated with 2.5% BSA-PBS served as controls. Static adhesion assays were performed for 30 min at 37°C, whereafter the fluorescence per well was measured with a Cytofluor II fluorometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.). Wells were washed three times with washing buffer (20 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2 mg/ml glucose, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM Mg2+, pH 7.4), and the fluorescence per well was measured again. The ratio of the latter fluorescent signal and the initial fluorescent signal was calculated, representing the percentage of adhered cells per well. The effect of PMA stimulation, integrin-blocking monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs), or dRGD-w peptide on leukemic cell adhesion was determined by preincubation of leukemic cells with PMA (100 ng/ml), MoAbs (10 μg/ml), or dRGD-w peptide (100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C, before static adhesion assays were performed. The divalent cations Mg2+ (5 mM) or Mn2+ (0.5 mM) were added to the leukemic cell suspension, just prior to performing the adhesion assay.

For adhesion assays of leukemic cells on a leptomeningeal cell layer, adhered leukemic cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. Five FITC images (1.3 mm2/image) of the central area of the leptomeningeal cell layer were obtained by using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DM IRHC; Leica Microsystems, Rijswijk, The Netherlands). The confluence of the leptomeningeal cell layer was confirmed by light microscopy. The number of adhered L1210 cells per FITC image was determined by quantitative analysis using Leica WIN software (Leica Microsystems), and high-magnification light microscopic pictures were made.

Proliferation Assays

For proliferation assays, L1210-S and L1210-A cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per noncoated well in a 48-well plate. Cells were cultured in either normal culture medium (RPMI, 10% fetal calf serum, PSG) or fresh CSF supplemented with 60 μM β-mercaptoethanol for 72 h. At 24, 48, and 72 h, the number of leukemic cells was counted by using a cell counter (Coulter particle counter, Becton Dickinson). For counting, cells were incubated with 10 mM EDTA (5 min, 37°C) and resuspended in 10 ml Isoton (Baker-Mallincrodt, Deventer, The Netherlands). The absence of residual adherent cells on the culture plates was confirmed by light microscopy. The mean number of cells of six wells (for culture medium) or three wells (for CSF) was calculated for each culture condition. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion in a separate well.

Induction of Leptomeningeal Metastases

Eight-week-old male DBA/2 mice were purchased from the Central Laboratory Animal Institute (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Leptomeningeal leukemia was induced as described previously for melanoma LM (Reijneveld et al., 1999). Briefly, L1210 leukemia cells were washed twice with PBS and suspended in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (Gibco). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion (>95% for all experiments). For survival studies of L1210-A and L1210-S leptomeningeal leukemia, 2 × 105 leukemic cells were injected in a volume of 10 μl into the cisterna magna. Neurological symptoms and survival were recorded every 24 h. Mice were defined as symptomatic when they showed more than 10% weight loss in combination with either (1) lethargy, (2) an arched back with a stretched neck, or (3) rotatory movements when lifted by the tail. For histologic studies, mice injected with L1210-A or L1210-S cells were sacrificed three or eight days after tumor inoculation. The brains, livers, spleens, and femurs were excised and directly fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded 5-μm brain and femur sections were stained with hematoxylineosin for morphological studies.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data obtained by immunofluorescence flow cytometry and static adhesion assays was performed using the Student’s t-test for independent samples. For comparison of survival data, a log-rank analysis of Kaplan-Meier curves was performed. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Selection of an Adherent Leukemic Cell Population from the L1210 Acute Lymphocytic Leukemic Suspension Cell Line

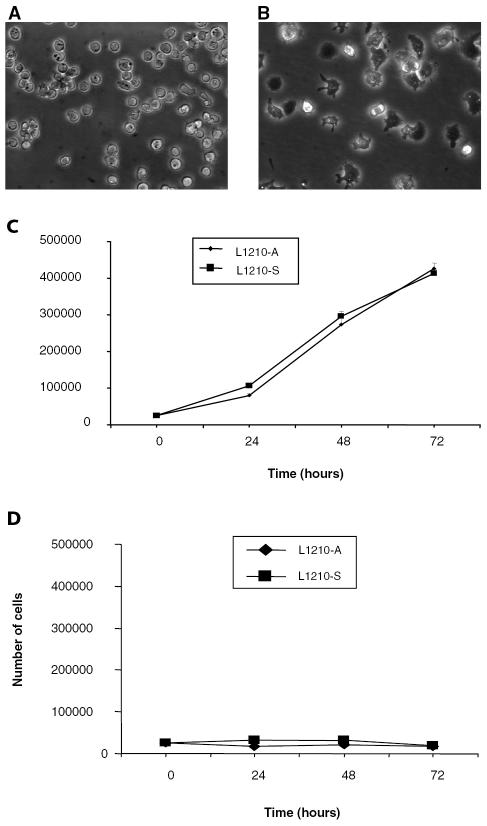

When culturing the L1210 acute lymphocytic leukemic suspension cell line (L1210-S cell line), a few cells (<1%) were noted to adhere strongly and spread on the bottom of noncoated culture flasks (Fig. 1A). These adherent cells were selectively cultured by aspirating the suspended L1210 cells every day for two weeks. Eventually, this resulted in the adherent L1210 cell line (L1210-A cell line), which formed extensive filopodia and lamellipodia on the bottom of the noncoated culture flask (Fig. 1B). When L1210-A cells were grown to confluence, suspended L1210-A cells appeared that adhered and spread again after they were placed in a new non-coated culture flask. In the L1210-S cell line, which was maintained as a suspension cell line, a few adherent cells (<1%) remained after each passage. Proliferation rates of the L1210-A and L1210-S cell lines in culture medium on noncoated wells were similar (Fig. 1C). Neither cell line proliferated in CSF on noncoated wells (Fig. 1D). Viability of the two leukemic cell lines was more than 95% during cell proliferation in both culture medium and CSF.

Fig. 1.

Morphological and proliferation characteristics of L1210-S and L1210-A cells. A and B. Light-microscopic pictures of L1210-S and L1210-A cells. Panel A shows the L1210 acute lymphocytic leukemic suspension cell line (L1210-S cell line). A few cells (<1%) strongly adhere and spread on the bottom of noncoated culture flasks. The adherent leukemic cells were selectively cultured by aspirating the suspended L1210 cells every day for two weeks, resulting in the adherent L1210 cell line (L1210-A), shown in panel B. These leukemic cells form extensive filopodia and lamellipodia on the bottom of the noncoated culture flask. C. Proliferation of L1210-S and L1210-A cells in culture medium. Leukemic cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells on noncoated wells of a 48-well plate in culture medium (RPMI, 10% fetal calf serum, 60 μM β-mercaptoethanol). At 24, 48, and 72 h, the number of leukemic cells was counted with a cell counter. The mean number of leukemic cells of six wells (± SEM) was plotted. One representative experiment out of six is shown. D. Proliferation of L1210-S and L1210-A cells in CSF. L1210-A and L1210-S cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells on non-coated wells of a 48-well plate in CSF supplemented with 60 μM β-mercaptoethanol. At 24, 48, and 72 h, the number of leukemic cells in three wells was counted with a cell counter. The mean number of leukemic cells (± SEM) is plotted. One representative experiment out of three is shown.

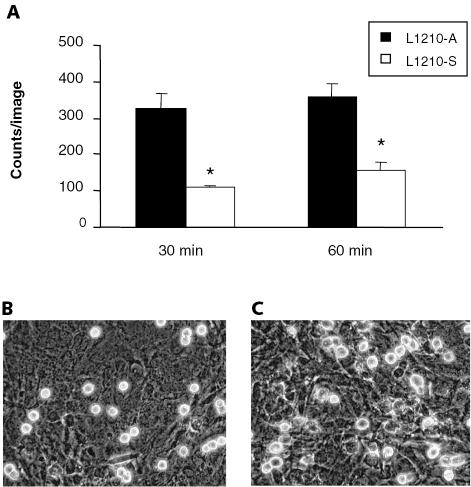

L1210 Cell Adhesion and Spreading on a Leptomeningeal Cell Layer

To investigate whether the two leukemic cell lines differed in capacity to bind to the leptomeninges, we performed static adhesion assays of L1210-S and L1210-A cells on leptomeningeal cell layers. A significantly higher number of L1210-A cells (327 ± 38 cells) adhered to a confluent leptomeningeal cell layer after 30 min of static adhesion as compared to the L1210-S cells (110 ± 6 cells) (P < 0.01, Fig. 2A). Similar results were found after 60 min of static adhesion: 357 ± 39 adhered L1210-A cells versus 155 ± 22 adhered L1210-S cells (P < 0.01 [Fig. 2A]). High magnification studies of the adhered leukemic cells after static adhesion during 60 min showed that all L1210-S cells were rounded up (Fig. 2B), whereas most of the adhered L1210-A cells were spread out, forming filopodia and lamellipodia on the leptomeningeal cell layer (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

L1210-A cells adhere and spread more efficiently to a leptomeningeal cell layer than do L1210-S cells. Adhesion assays of fluorescently labeled leukemic cells to determine adhesion to a leptomeningeal cell layer were performed at 37°C for 30 or 60 min, whereafter nonadherent cells were washed away and adhered cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. A. The mean number of leukemic cells (± SEM) that adhered to the leptomeningeal cell layer after 30 and 60 min of static adhesion is plotted. Two independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate. B and C. Light-microscopic pictures of L1210-S cells (B) and L1210-A cells (C) that adhered to a leptomeningeal cell layer after 60 min of static adhesion. 40×.

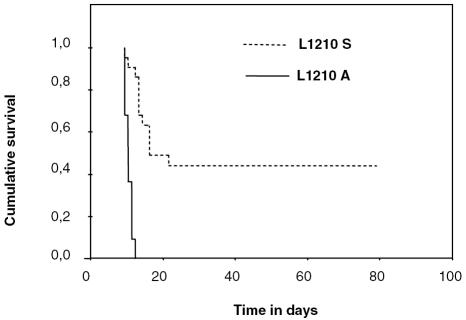

Significant Survival Difference Between L1210-A and L1210-S Leptomeningeal Leukemia

To determine whether a difference in the capacity of the two leukemic cell lines to adhere to the leptomeninges in vitro translated into a more aggressive behavior in vivo, we performed survival studies of mice with leptomeningeal leukemia. All mice that were injected intrathecally with L1210-A cells (2 × 105 cells) died of LM within 12 days (median survival time, 10 days; n = 22, obtained in four experiments with at least five mice per group). In contrast, intracisternal L1210-S cell injection resulted in prolonged survival, with 45% of the mice as long-term survivors (median survival time, 16 days; n = 22; hazard ratio of L1210-A vs. L1210-S, 16.5; 95% confidence interval, 4.7–58; P < 0.001; Fig. 3). No leukemic infiltration of bone marrow was seen in any of the mice and spleen, and the weight of liver and spleen of mice with leptomeningeal leukemia was not increased as compared to that of normal mice (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Significant difference in survival of mice with L1210-A and mice with L1210-S leptomeningeal leukemia. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice intrathecally injected with L1210-A cells (solid line; n = 22) or L1210-S cells (dashed line; n = 22). Leukemic cells (2 × 105) were injected into the cisterna magna of the mice, and survival was recorded.

Adhesion Molecule Expression on L1210-A and L1210-S cells

To find the cellular mechanism or mechanisms that underlie the increased adhesive capacity of L1210-A cells as compared to that of L1210-S cells, we studied the expression levels of a number of adhesion molecules on the two leukemic cell lines by using immunofluorescence flow cytometry. Both cell types showed similar, low expression levels of β2 integrin subunits (CD18) and ICAM-1 (CD54). Similar high expression levels of CD44 (hyaluronate receptor, phagocyte glycoprotein, or Pgp-1) were found on both leukemic cell lines. L-selectin (CD62L) was not expressed on either cell line. The β1 integrin subunit (CD29) and β3 integrin subunit (CD61) expression levels were low in both cell lines, but slightly higher in L1210-A cells than in L1210-S cells (Table 1). Furthermore, low expression levels of the αv integrin subunits were found in the L1210-A cells (mean fluorescence intensity = 7.8 ± 0.4) as compared to the L1210-S cells (mean fluorescence intensity = 4.9 ± 1.2; n = 2), whereas no expression of the αiib integrin subunit was found on either leukemic cell type (data not shown).

Table 1.

Expression levels of adhesion molecules on L1210-A and L1210-S cells*

| Adhesion Molecule | L1210-A cells | L1210-S cells |

|---|---|---|

| Rat IgG2a/rat FITC | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.7 |

| Rat IgG1/2b/rat FITC | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 1.7 |

| Hamster IgG1/hamster FITC | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 1.1 |

| β1 integrin/rat FITC (rat IgG2a) | 26.8 ± 1.6 | 20.3 ± 1.3 |

| β2 integrin/rat FITC (rat IgG1/2b) | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 13.6 ± 1.6 |

| β3 integrin/hamster FITC | 17.0 ± 0.9 | 8.3 ± 0.4 |

| ICAM-1/hamster FITC | 26.0 ± 1.7 | 23.9 ± 3.6 |

| L-selectin/rat FITC (rat IgG2a) | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.8 |

| CD44/rat FITC (rat IgG1/2b) | 66.1 ± 10.8 | 42.5 ± 6.6 |

Abbreviations: FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

The expression levels of β1, β2, and β3 integrin subunits, ICAM-1, L-selectin, and CD44 were determined by immunofluorescence flow cytometry. The mean of the mean fluorescence intensity ± SEM is indicated as measured in three or more experiments.

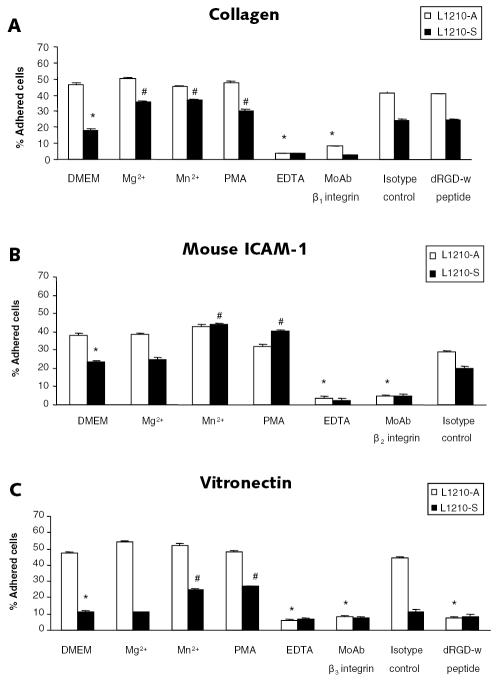

Constitutively Active β1, β2, and β3 Integrins on L1210-A Cells

Not the integrin expression level but in particular the integrin activation state determines cell adhesion (Diamond and Springer, 1993; Lum et al., 2002). Therefore, we studied the activation state of β1, β2, and β3 integrins in the two leukemic cell lines. We performed static adhesion assays using wells coated with ligands for β1 integrin (collagen), β2 integrin (mouse ICAM-1), and β3 integrin (vitronectin) in the presence of extracellular factors that activate integrins (Mg2+, Mn2+, or PMA) or agents blocking integrin-ligand interactions (integrin-blocking MoAbs, dRGD-w peptide, or EDTA). Levels of L1210-A cell binding to collagen (Fig. 4A), mouse ICAM-1 (Fig. 4B), and vitronectin (Fig. 4C) were significantly higher than L1210-S cell binding levels; 47% ± 2% of the L1210-A cells versus 18% ± 4% of the L1210-S cells adhered to collagen, 38% ± 1% of the L1210-A cells versus 23% ± 4% of the L1210-S cells adhered to mouse ICAM-1, and 47% ± 2% of the L1210-A cells versus 12% ± 1% of the L1210-S cells adhered to vitronectin after 30 min of static adhesion. Leukemic cell binding on all matrix proteins was blocked completely by 10 mM EDTA, which prevents integrin-ligand interaction by capturing divalent cations. β1 integrin-blocking MoAb completely blocked leukemic cell binding to collagen. Leukemic cell binding to mouse ICAM-1 was fully prevented by β2 integrin-blocking MoAb. Finally, both dRGD-w peptide and β3 integrin-blocking MoAb completely prevented leukemic cell binding to vitronectin. No effect on leukemic cell binding to collagen, mouse ICAM-1, or vitronectin was seen for the isotype controls of the integrin-blocking MoAbs. Levels of L1210-S cell binding to collagen, mouse ICAM-1, and vitronectin were significantly increased by PMA and Mn2+. Moreover, L1210-S cell binding to collagen was also significantly increased by Mg2+. Both Mg2+ and Mn2+ are known to force the integrin in a high-affinity state (Hogg and Leitinger, 2001; Mould et al., 1995), whereas PMA can induce integrin clustering on the cell membrane (avidity change) in a protein kinase C–dependent way (Peter and O’Toole, 1995; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000). However, the extracellular factors Mg2+, Mn2+, or PMA did not further enhance L1210-A cell binding to collagen, mouse ICAM-1, or vitronectin.

Fig. 4.

β1, β2, and β3 integrins are constitutively active on L1210-A cells. Static adhesion assays of leukemic cells were performed on collagen (A), mouse ICAM-1 (B), and vitronectin (C). Assays were done without extracellular stimulation (DMEM); in the presence of Mg2+ (5 mM), Mn2+ (0.5 mM), or EDTA (10 mM); or after pretreatment of leukemic cells with PMA (100 ng/ml), integrin-blocking or isotype control MoAbs (10 μg/ml), or dRGD-w peptide (100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. The percentage of adhered cells after 30 min of static adhesion and three washing steps is plotted on the y-axis. White and black bars represent the mean percentage of adhered L1210-A and L1210-S cells (± SEM), respectively. Data were obtained from more than three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *Significantly different compared to the mean percentage adhered L1210-A cells in DMEM. #Significantly different compared to the mean percentage adhered L1210-S cells in DMEM.

Effect of Mn2+ on L1210-S Cell Adhesion and β3 Integrin on L1210-A Cell Adhesion

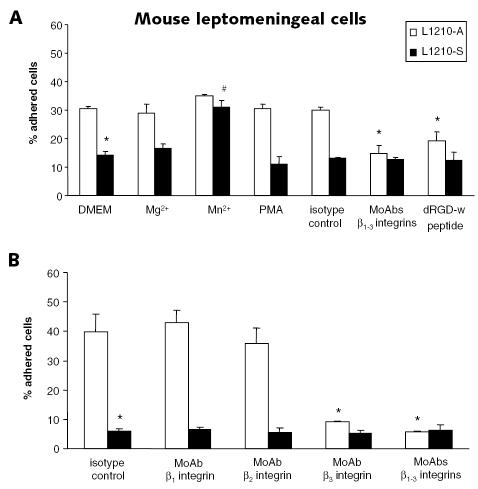

To determine whether changes in integrin activation state influence the capacity of leukemic cells to adhere to the leptomeninges, we performed in vitro static adhesion assays of L1210-S and L1210-A cells by using confluent primary mouse leptomeningeal cell layers in the presence of Mg2+, Mn2+, or PMA. L1210-S cell binding to mouse leptomeningeal cell layers was significantly increased by Mn2+, but not by Mg2+ or PMA. However, Mg2+, Mn2+, or PMA did not further enhance L1210-A cell binding to mouse leptomeningeal cells. L1210-A cell binding to leptomeningeal cells was strongly inhibited by blocking β1, β2, and β3 integrins with MoAbs and to a slightly lesser extent by dRGD-w peptide as compared to the isotype control MoAbs. No further significant decrease in L1210-S cell adhesion to the leptomeningeal cells was seen in the presence of integrin-blocking MoAbs or dRGD-w peptide (Fig. 5A). To further dissect the individual roles of the β1, β2, and β3 integrins, adhesion assays on primary leptomeningeal cells were performed in the presence of MoAbs against the single β integrin subunits. Figure 5B shows that the adhesion of the L1210-A cells to the leptomeningeal cell layer is almost completely β3 integrin dependent (P < 0.03 compared to isotype control antibodies).

Fig. 5.

Mn2+ induces L1210-S cell adhesion to a leptomeningeal cell layer and L1210-A cell adhesion is β3 integrin dependent. A. Static adhesion assays of leukemic cells were performed on confluent mouse leptomeningeal cell layers without extracellular stimulation (DMEM); in the presence of Mg2+ (5 mM) or Mn2+ (0.5 mM); or after pretreatment of leukemic cells with PMA (100 ng/ml), β1, β2, β3 integrin-blocking or isotype control MoAbs (10 μg/ml), or dRGD-w peptide (100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. B. Static adhesion assays of leukemic cells on confluent mouse leptomeningeal cell layers were performed after pretreatment of leukemic cells with MoAbs against the single β1, β2, or β3 integrin subunits (10 μg/ml) or all three β integrin chains, and results were compared to results for pretreatment with the isotype control MoAbs (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The percentage of adhered cells after 30 min of static adhesion and three washing steps is plotted on the y-axis. White and black bars represent the mean percentage of adhered L1210-A and L1210-S cells (± SEM), respectively. Data were obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *Significantly different compared to the mean percentage adhered L1210-A cells in DMEM or after pretreatment with isotype control MoAbs. #Significantly different compared to the mean percentage adhered L1210-S cells in DMEM.

Discussion

We show that constitutive integrin activation on leukemic cells contributes to leptomeningeal leukemia. For this, we used adherent and suspension forms of a leukemic cell line, which had similar proliferation rates in culture medium but differed in adhesion and spreading capacity on a leptomeningeal cell layer in vitro. We found that the adherent leukemic cell population, but not the suspension leukemic cell population, led to rapid death in a leptomeningeal leukemia mouse model. We showed that β1, β2, and β3 integrins are in a constitutively high activation state on the L1210-A cells and in a low, but inducible activation state on L1210-S cells. The suspension cell line was converted to the adherent phenotype by activating the integrins with divalent cations (matrix proteins and mouse leptomeningeal cells) or PMA (matrix proteins). Our data point to an abberantly regulated inside-out signaling pathway of integrins in tumor cells as a novel mechanism of LM progression. Integrin activation on hematopoetic cells is a tightly regulated process under physiological circumstances (Calvete, 1994; Ley, 2002). Circulating leukocytes maintain their integrins in a low-activity state, which can rapidly be changed into an intermediate or a highly active state by chemokine-triggered inside-out intracellular signaling pathways (Hynes, 1992; Shimizu et al., 1999). Under pathological conditions, such as an infection, chemokines are present on the endothelial cells and activate integrins on leukocytes, which subsequently leads to leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium and transmigration into the tissue. It has been shown that only a small percentage of activated integrins is needed to reach maximum levels of leukocyte adhesion, which renders the expression level of integrins as less important than their activation state (Diamond and Springer, 1993; Lum et al., 2002). Therefore, the small differences in β1 and β3 integrin expression levels of the two leukemic cell lines may contribute to the survival difference, but the difference in activation state of the β1, β2, and β3 integrins is considered to be more important. The β1 integrins potentially mediating leukemic cell adhesion to collagen are the α1β1 and α2β1 integrins, since these integrins are known to be expressed on leukocytes and interact with collagen in a non-RGD-dependent way, as was found for the L1210-A cells (Ben Horin and Bank, 2004; Gendron et al., 2003). αLβ2 integrins on the leukemic cells most likely recognize ICAM-1, because these integrins are expressed on lymphocytes, whereas αMβ2 integrins are present only on leukocytes of the myeloid lineage (Li, 1999; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000). Several integrins (αvβ5, αvβ3, αvβ1, α8β1, and αiibβ3) potentially interact with vitronectin (Hynes, 2002). We consider it most likely that for the L1210 cells αvβ3 integrins mediate the adhesion to vitronectin, as leukemic cell adhesion was largely β3 integrin dependent, and low expression levels of the αv integrin subunit but not αiib integrin subunit were found on the L1210-A cells.

Several studies suggest that the inside-out signaling of integrins in tumor cells can be dysregulated, which can lead both to adhesion defects due to integrin inactivity and to increased adhesion caused by constitutive integrin activation. Geijtenbeek et al. (1999) demonstrated αLβ2 integrin and α4β1 integrin–mediated adhesion defects in leukemic cells isolated from bone marrow of patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Trusolino et al. (1998) found that αvβ3 integrins on thyroid carcinoma were highly active and enriched at focal contacts, mediating tight adhesion, whereas these integrins were in a latent state on normal thyroid cells, which could not form cytoskeletal connections and promote cell adhesion. An autocrine loop of the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor and a constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated receptor were thought to be responsible for the high αvβ3 integrin–activated state in the thyroid carcinoma cells. Felding-Habermann et al. (2001) showed that constitutively activated αvβ3 integrins, but not the nonactivated form, promoted distant metastases of mammary carcinoma. This finding was attributed to αvβ3 integrin–mediated interaction of tumor cells with platelets, which supports tumor cell arrest to the blood vessel wall.

Here we show that constitutive integrin activation on leukemic cells contributes to leptomeningeal leukemia. We attribute this finding to an increased integrin-mediated leukemic cell adhesion to the leptomeninges, which was mostly β3 integrin dependent as determined in in vitro assays to determine the adhesion of leukemic cells to a primary leptomeningeal cell layer. Three hypotheses were formulated to explain integrin-mediated LM progression: (I) direct integrin-ligand interactions between adhered cells and leptomeningeal cells/matrix proteins lead to survival or proliferation signaling, (II) adhered cells proliferate faster than cells in suspension, because the leptomeningeal vasculature provides nutrients, growth factors, and oxygen to the adhered cells more efficiently, and (III) proliferating, adhered leukemic cells can form tumor masses that induce angiogenesis. Our finding that leukemic cells do not proliferate in the CSF underscores the relevance of tumor cell adhesion to the leptomeninges in LM progression. No data were found to support the first hypothesis, because binding of leukemic cells to either collagen or vitronectin could not induce leukemic cell proliferation in CSF (data not shown). The second and third hypotheses are therefore more likely to explain integrin-mediated LM progression.

Integrin activation is a combination of integrin affinity and avidity changes. The constitutively activated state of β1, β2, and β3 integrins on L1210-A cells is likely to be caused by an increase in both integrin affinity and integrin avidity, since Mn2+ (affinity change) as well as PMA (avidity change) significantly increased adhesion of L1210-S cells to collagen, mouse ICAM-1, and vitronectin. Only L1210-S cell binding to collagen was induced by Mg2+, known to be less potent in changing the affinity state of integrins than is Mn2+. Surprisingly, L1210-S cell binding to mouse leptomeningeal cells was induced only by Mn2+ and not by PMA, which suggests that integrin affinity is more important than integrin avidity for tumor cell adhesion to the leptomeninges.

It is tempting to speculate about the intracellular factor(s) being dysregulated in tumor cells with constitutively active integrins. R-ras, a member of the Ras family of small GTP-binding proteins, and its downstream effector, Raf-1, are interesting proteins in this respect, because they are involved in both integrin activation and oncogenesis (Hughes et al., 1997; Sethi et al., 1999). The Ras-related GTPase protein, Rap-1, a protein that has been shown to be a key regulator of integrin activation in leukocytes, may be another interesting candidate (Katagiri et al., 2000; Reedquist et al., 2000; Shimonaka et al., 2003). Future research will focus on unraveling the intracellular inside-out signaling defects that lead to constitutively activated integrins on tumor cells. Ultimately, this research should lead to the development of agents that efficiently block tumor cell adhesion in order to prevent LM progression.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (NKB) to J.C. Reijneveld and from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) to J.C. Reijneveld (reg. nr. 920-03-075), D. Brandsma (reg. nr. 920-03-138), and L. Ulfman (reg. nr. 916-36-051).

Abbreviations used are as follows: BSA, bovine serum albumin; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EGTA, ethylene glycol-bis tetraacetic acid; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; MoAb, monoclonal antibody; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; PSG, penicillin–streptomycin–l-glutamine; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.

References

- Balis FM, Savitch JL, Bleyer WA, Reaman GH, Poplack DG. Remission induction of meningeal leukemia with high-dose intravenous methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:485–489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Horin S, Bank I. The role of very late antigen-1 in immune-mediated inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2004;113:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer WA, Byrne TN. Leptomeningeal cancer in leukemia and solid tumors. Curr Probl Cancer. 1988;12:181–238. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(88)80001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandsma D, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ, de Boer HC, Gebbink MF, Ulfman LH, Zwaginga JJ, Voest EE. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is a key adhesion molecule in melanoma cell adhesion to the leptomeninges. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1493–1502. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000036876.08970.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete JJ. Clues for understanding the structure and function of a prototypic human integrin: The platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BM, Matsuura N, Takada Y, Zetter BR, Hemler ME. In vitro and in vivo consequences of VLA-2 expression on rhabdomyo-sarcoma cells. Science. 1991;251:1600–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.2011740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colocci N, Glantz M, Recht L. Prevention and treatment of central nervous system involvement by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A review of the literature. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:395–404. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis LM. Current diagnosis and treatment of leptomeningeal metastasis. J Neurooncol. 1998;38:245–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1005956925637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Springer TA. A subpopulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) molecules mediates neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 and fibrinogen. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:545–556. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B, O’Toole TE, Smith JW, Fransvea E, Ruggeri ZM, Ginsberg MH, Hughes PE, Pampori N, Shattil SJ, Saven A, Mueller BM. Integrin activation controls metastasis in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1853–1858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick J, Ritch PS, Hansen RM, Anderson T. Successful treatment of meningeal leukemia using systemic high-dose cytosine arabinoside. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:365–368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y, van Vliet SJ, Renes MH, Raymakers RA, Figdor CG. High frequency of adhesion defects in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:754–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron S, Couture J, Aoudjit F. Integrin α2β1 inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis in T lymphocytes by protein phosphatase 2A-dependent activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48633–48643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese A, Laube B, Zapf S, Mangold U, Westphal M. Glioma cell adhesion and migration on human brain sections. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2435–2447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosslar U, Jonas P, Luz A, Lifka A, Naor D, Hamann A, Holzmann B. Predominant role of alpha 4-integrins for distinct steps of lymphoma metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4821–4826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R, Naylor B, Greenberg HS, Junck L. Clinical outcome in aggressively treated meningeal carcinomatosis. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:457–461. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540170033013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg N, Leitinger B. Shape and shift changes related to the function of leukocyte integrins LFA-1 and Mac-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:893–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PE, Renshaw MW, Pfaff M, Forsyth J, Keivens VM, Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Suppression of integrin activation: A novel function of a Ras/Raf-initiated MAP kinase pathway. Cell. 1997;88:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81892-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: Versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri K, Hattori M, Minato N, Irie S, Takatsu K, Kinashi T. Rap1 is a potent activation signal for leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 distinct from protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1956–1969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.1956-1969.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris CP. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. How does cancer reach the pia-arachnoid? Cancer. 1983;51:154–160. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830101)51:1<154::aid-cncr2820510130>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K. Integration of inflammatory signals by rolling neutrophils. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:8–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. The alphaMbeta2 integrin and its role in neutrophil function. Cell Res. 1999;9:171–178. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum AF, Green CE, Lee GR, Staunton DE, Simon SI. Dynamic regulation of LFA-1 activation and neutrophil arrest on intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in shear flow. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20660–20670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould AP, Akiyama SK, Humphries MJ. Regulation of integrin α5β1-fibronectin interactions by divalent cations. Evidence for distinct classes of binding sites for Mn2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26270–26277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson ME, Chernik NL, Posner JB. Infiltration of the leptomeninges by systemic cancer. A clinical and pathologic study. Arch Neurol. 1974;30:122–137. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490320010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter K, O’Toole TE. Modulation of cell adhesion by changes in α L β 2 (LFA-1, CD11a/CD18) cytoplasmic domain/cytoskeleton interaction. J Exp Med. 1995;181:315–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedquist KA, Ross E, Koop EA, Wolthuis RM, Zwartkruis FJ, van Kooyk Y, Salmon M, Buckley CD, Bos JL. The small GTPase, Rap1, mediates CD31-induced integrin adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1151–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ, Voest EE. A simple mouse model for leptomeningeal metastases and repeated intrathecal therapy. J Neurooncol. 1999;42:137–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1006237917632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ST, Aisner J, Makuch RW, Matthews MJ, Ihde DC, Whitacre M, Glatstein EJ, Wiernik PH, Lichter AS, Bunn PA., Jr Carcinomatous leptomeningitis in small cell lung cancer: A clinicopathologic review of the National Cancer Institute experience. Medicine. 1982;61:45–53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E. Fibronectin and its integrin receptors in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1999;76:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: Emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi T, Ginsberg MH, Downward J, Hughes PE. The small GTP-binding protein R-Ras can influence integrin activation by antagonizing a Ras/Raf-initiated integrin suppression pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1799–1809. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Rose DM, Ginsberg MH. Integrins in the immune system. Adv Immunol. 1999;72:325–380. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimonaka M, Katagiri K, Nakayama T, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Yoshie O, Kinashi T. Rap1 translates chemokine signals to integrin activation, cell polarization, and motility across vascular endothelium under flow. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:417–427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusolino L, Serini G, Cecchini G, Besati C, Ambesi-Impiombato FS, Marchisio PC, De Filippi R. Growth factor-dependent activation of alphavbeta3 integrin in normal epithelial cells: Implications for tumor invasion. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1145–1156. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ree TC, Dippel DW, Avezaat CJ, Sillevis Smitt PA, Vecht CJ, van den Bent MJ. Leptomeningeal metastasis after surgical resection of brain metastases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:225–227. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Avidity regulation of integrins: The driving force in leukocyte adhesion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:542–547. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatohgo T, Izumi M, Kashiwagi H, Hayashi M. Novel purification of vitronectin from human plasma by heparin affinity chromatography. Cell Struct Funct. 1988;13:281–292. doi: 10.1247/csf.13.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]