Abstract

Cryptosporidium parvum is an intracellular protozoan parasite that causes a severe diarrheal illness of unclear etiology. Also unclear is the fate of the host cell upon parasite egress. We show in an MDCK cell model that the host cell is killed upon parasite egress; this death is necrotic, rather than apoptotic, in nature.

The obligate intracellular protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum causes a diarrheal illness in infected hosts (5, 7). While the life cycle of the parasite is understood, it is unclear what aspect of the host-parasite interaction causes disease. During the invasion process, Cryptosporidium establishes an intracellular compartment within the host cell from which it ruptures after its intracellular development (12, 14, 21, 22).

It has been reported that Cryptosporidium infection induces caspase-dependent apoptosis of in vitro-infected cell lines (2, 4, 15, 16, 23), but it is unclear if these observations are unique to the in vitro system. In one study of intestinal biopsy samples from AIDS patients with cryptosporidiosis, there was no association of the intensity of small bowel infection with apoptosis (13). Supporting this in vivo observation is the finding that Cryptosporidium gives infected cells protection against apoptosis (3, 10, 15). This protection was effective in the presence of strong apoptosis-inducing agents and appears to be mediated by an NF-κB pathway (11). Another study suggested that there is no increase in apoptosis among Cryptosporidium-infected cells but that there is increased apoptosis in uninfected neighboring cells, explaining the previously observed increase in vitro apoptosis (4). Most of these investigations examined populations of infected cells several hours after infection; thus, the effects could not be correlated with specific events in the parasite life cycle. Our goal was to gain a better understanding of Cryptosporidium pathology by examining the fate of individual C. parvum-infected cells during parasite egress.

In order to investigate the fate of the individual Cryptosporidium-infected host cell over time, we first designed and tested an in vitro system that identifies changes in cell permeability and mechanisms of cell death by using time lapse video microscopy. We then used this system to examine host cell permeability and death upon Cryptosporidium egress. Human intestinal epithelial cell lines (HCT-8, Caco-2, and HT29) have been extensively used for Cryptosporidium research; however, they are inappropriate for this study since they are known to have p53 gene mutations, which could alter their susceptibility to apoptosis (19, 20). Instead, Madin Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC CCL-34) were chosen for the following reasons: (i) they are a well-studied model for apoptosis (18), and (ii) they form a polarized monolayer that is easily infected by Cryptosporidium. MDCK cells were grown to confluence on glass 35-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes (MatTek Corp., Ashland, Mass.) and infected with Cryptosporidium oocysts (Iowa isolate) as previously described (8, 9). Since time lapse video microscopy of living cells does not permit the use of antibodies or toxic reagents that have been used to study cell death in fixed cells, it was necessary to visualize cell changes by use of another system. In order to clearly identify host cells and parasites, cells were stained with a membrane-permeable DNA stain (Hoechst 33342 [Molecular Probes catalog number H-3570]; 2 μg/ml) and a membrane-permeable mitochondrial membrane-potential stain (MitoTracker [Molecular Probes catalog number #M7512]; 0.02 μg/ml), which stained functional mitochondria and, fortuitously, intracellular parasites (see Fig. 2C and D). To assess the integrity of the cell membrane, a membrane-impermeable DNA stain that stains only the nuclei of permeabilized cells was added to the medium (SYTOX green; 1 μM [Molecular Probes Catalog number S-7020]).

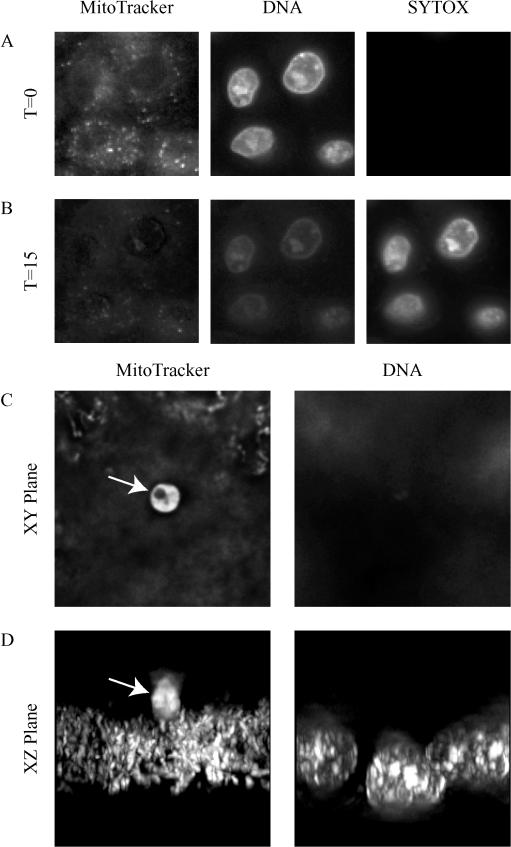

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence microscopy of an MDCK cell monolayer showing permeabilization of the cells by saponin (A and B) and MitoTracker staining of parasites (C and D). At 15 min after saponin addition (B), the nuclei are brightly stained with the SYTOX green dye, indicating plasma membrane disruption that allows nuclear staining. Note that there is an associated decrease in brightness of the MitoTracker staining, indicating a decrease in the membrane potential of the mitochondria. Panel C shows a C. parvum-infected MDCK cell monolayer stained with MitoTracker and Hoechst stain. Note the parasite in panels C and D (arrows). It is not known how the Hoechst nuclear dye is excluded from the parasite. Panel D shows the same field in cross section (an xz view), clearly demonstrating that the parasite (arrow) is above the monolayer. These images are projections of a deconvolved stack of images. T, time in minutes. Original magnification, ×400.

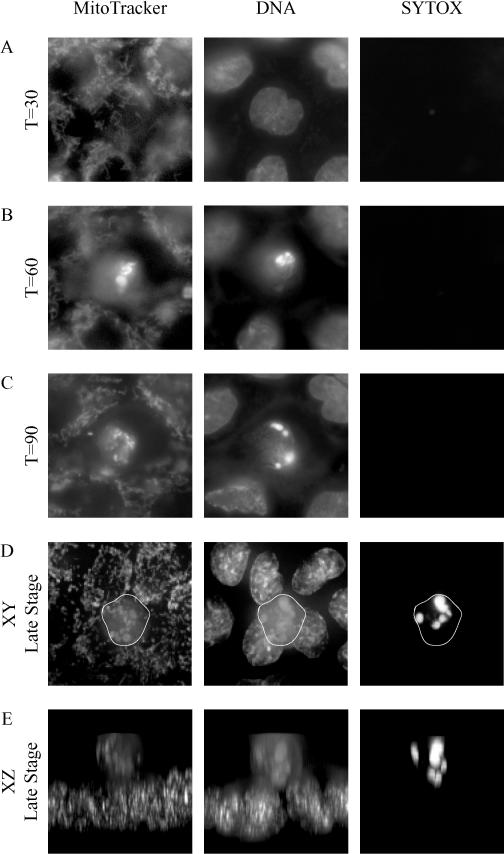

To identify characteristic features of apoptosis in this system, MDCK cells were exposed to 360 kJ shortwave UV radiation for 3 min (Stratalinker 2400) to induce apoptosis (18). The nuclear fragmentation that is characteristic of apoptosis was highlighted by the nuclear stain (Fig. 1B and C). There was no staining of the DNA with the membrane-impermeable dye (SYTOX green), indicating that the plasma membrane remains intact during early apoptosis. By using deconvolution microscopy, an apoptotic MDCK cell in our system that had been extruded from the monolayer was demonstrated, as shown in Fig. 1D and E (Delta Vision microscope and SoftWoRx version 2.5; Applied Precision, Issaquah, Wash.). The fragmentation of its nucleus was highlighted by the Hoechst and SYTOX dyes.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence microscopy of MDCK cells showing apoptosis at different stages following UV irradiation. Staining was done with MitoTracker, Hoechst stain for DNA, and SYTOX green, which stains DNA in permeable cells. At 60 min after the induction of apoptosis by UV irradiation (B), the nucleus assumes the characteristic fragmented appearance associated with apoptosis. Also note that 90 min after UV irradiation (C), there is no staining with the SYTOX green stain, indicating that the plasma membrane of the cell is intact. Panel D shows a late-stage (time [T] ≈120-min) apoptotic cell (outlined) being extruded from the monolayer. Panel E shows the same cell, but in cross section (an xz view), clearly demonstrating that the cell has been extruded from the monolayer. Note the fragmented nuclear staining by Hoechst stain and SYTOX green, typical of apoptosis. Original magnification, ×400.

To evaluate the integrity of host cell plasma membranes in this system, saponin was added to the MDCK cells to selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane. In cells with intact plasma membranes, SYTOX green is excluded from cells, preventing nuclear staining, but when the plasma membrane is disrupted, SYTOX green enters the cell and stains the nucleus. Figure 2A demonstrates the exclusion of SYTOX green from intact MDCK cells but rapid nuclear staining after exposure to saponin (Fig. 2B). The nuclear morphology of the intact MDCK cells is stable for at least 8 h after permeabilization, unlike that of apoptotic cells. Also unlike the apoptotic cells, the mitochondria lose their electrical potential, as demonstrated by loss of MitoTracker staining (Fig. 2B).

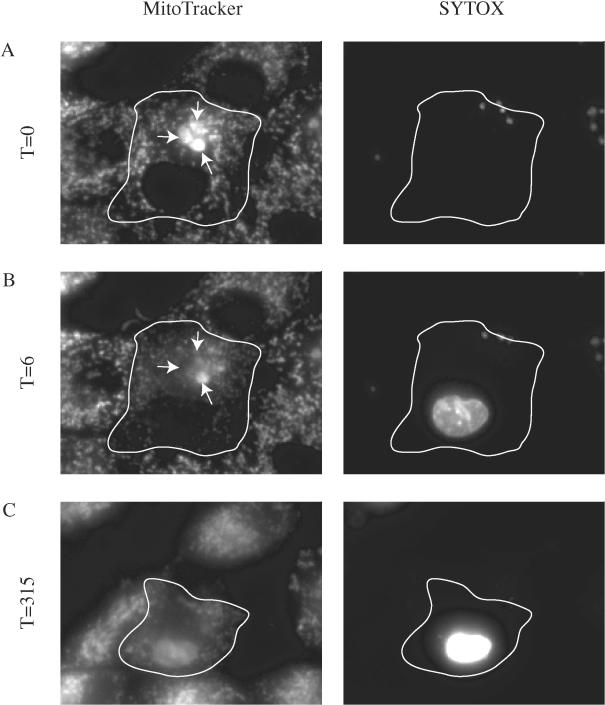

The egress of merozoites from three meronts is shown over time in Fig. 3. It is clear that in less than 15 min after the parasites exit (Fig. 3A), the nucleus of the cell is strongly stained with SYTOX green, indicating that the cell has been permeabilized. Six minutes after egress, the mitochondrial staining has decreased by 41%, which suggests a loss of mitochondrial function. After 5 h, the nuclear morphology still appears normal even though the cell is dead, as indicated by the permanent loss of mitochondrial staining. Even at this late time point, the cell has not been extruded from the monolayer, as is commonly seen within 1 to 2 h after the induction of apoptosis. (The movie from which these images have been taken is available at http://homepage.mac.com/fitzrobert/PaperFigure.mov). These results suggest that C. parvum egress induces a defect in the host plasma membrane, followed by nonapoptotic cell death. These are consistent findings that have been documented in 12 parasite egress events during seven independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence microscopy of a C. parvum-infected MDCK cell line documenting host cell fate as parasites exit a cell. Three intracellular parasites (meronts) are stained with MitoTracker (arrows) in a single MDCK cell (outlined). Parasite egress is documented by an abrupt loss of MitoTracker-stained parasites (B panel arrows). Labeling is with MitoTracker and SYTOX green to stain nucleic acids in permeable cells. At 6 min after parasite egress (B), the MDCK cell nucleus is clearly stained with the membrane-impermeable DNA dye (SYTOX green), indicating that the host cell is now permeable. Note that there is an associated decrease in brightness of the MitoTracker staining of the mitochondria, indicating a decrease in the membrane potential. Also note that 315 min after parasite egress (C) the mitochondrial staining remains dim and that the nucleus is intact and staining brightly with the SYTOX green dye. This combination of permanent loss of mitochondrial function and the permeabilization of the cell membrane indicates that the cell is dead. Note also that there is no evidence of nuclear fragmentation to indicate apoptosis. T, time in minutes Original magnification, ×400.

Apoptotic and necrotic cell death can be easily distinguished by morphologic features and specific biochemical changes. Apoptosis involves a highly regulated pathway that leads to the controlled destruction of the cell (17). This process involves fragmentation of the DNA, loss of mitochondrial function, and cytoskeletal disruption manifested as cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, and membrane blebbing. Necrotic cell death is a contrasting form of cell death resulting from cellular injury that is associated with an early loss of plasma membrane integrity; this loss results in leakage of cell contents, which can initiate an inflammatory response. In contrast to necrotic cells, apoptotic epithelial cells maintain their plasma membrane integrity until late in the death process (18).

In a system using the MDCK cell line, we have shown that upon its egress from a host cell, Cryptosporidium induces a defect in the plasma membrane of that cell. This is demonstrated by staining the host cell nucleus with a membrane-impermeable dye within 6 min of parasite egress. Over the next several hours, the nucleus remains morphologically intact, without evidence of apoptotic changes. Also, during this time, the mitochondria cease functioning, as demonstrated by a dye that recognizes electrochemical gradients. Taken together, these findings indicate that Cryptosporidium induces a nonapoptotic death in host cells upon egress.

If this conclusion is true in vivo, this nonapoptotic death may play several roles in the pathogenesis of the diarrhea induced by Cryptosporidium. It has previously been shown that Cryptosporidium induces a decrease in resistance across epithelial monolayers and mucosa, indicative of damage to the tight junctions between cells (6) or holes in the monolayer resulting from missing cells. It seems likely that the necrotic cell death induced by Cryptosporidium would contribute to this lack of epithelial integrity. Interestingly, even high levels of apoptosis do not alter the resistance of epithelial cell monolayers (18). It is also possible that nonapoptotic cell death plays a role in triggering the host immune reaction to Cryptosporidium (6). Future studies may further elucidate the relationship between the parasite life cycle and the pathogenesis of cryptosporidiosis.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the following individuals for many helpful discussions and technical assistance: Vern Carruthers, Carol Cooke, Paul Englund, Doug Murphy, and Cindy Sears. We also thank Stacy Mazzalupo for reviewing the manuscript.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Argenzio, R. A., J. A. Liacos, M. L. Levy, D. J. Meuten, J. G. Lecce, and D. W. Powell. 1990. Villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, cellular infiltration, and impaired glucose-Na absorption in enteric cryptosporidiosis of pigs. Gastroenterology 98:1129-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, X. M., G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 1999. Cryptosporidium parvum induces apoptosis in biliary epithelia by a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. 277:G599-G608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, X. M., S. A. Levine, P. L. Splinter, P. S. Tietz, A. L. Ganong, C. Jobin, G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 2001. Cryptosporidium parvum activates nuclear factor κB in biliary epithelia preventing epithelial cell apoptosis. Gastroenterology 120:1774-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X. M., S. A. Levine, P. Tietz, E. Krueger, M. A. McNiven, D. M. Jefferson, M. Mahle, and N. F. LaRusso. 1998. Cryptosporidium parvum is cytopathic for cultured human biliary epithelia via an apoptotic mechanism. Hepatology 28:906-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, D. P. 1999. New insights into human cryptosporidiosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:554-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, D. P., and C. L. Sears. 1996. The pathogenesis of cryptosporidiosis. Parasitol. Today 12:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Current, W. L., and L. S. Garcia. 1991. Cryptosporidiosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:325-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott, D. A., and D. P. Clark. 2000. Cryptosporidium parvum induces host cell actin accumulation at the host-parasite interface. Infect. Immun. 68:2315-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott, D. A., D. J. Coleman, M. A. Lane, R. C. May, L. M. Machesky, and D. P. Clark. 2001. Cryptosporidium parvum infection requires host cell actin polymerization. Infect. Immun. 69:5940-5942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heussler, V. T., P. Kuenzi, and S. Rottenberg. 2001. Inhibition of apoptosis by intracellular protozoan parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1166-1176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Laurent, F., L. Eckmann, T. C. Savidge, G. Morgan, C. Theodos, M. Naciri, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1997. Cryptosporidium parvum infection of human intestinal epithelial cells induces the polarized secretion of C-X-C chemokines. Infect. Immun. 65:5067-5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefkowitch, J. H., S. Krumholz, K. C. Feng-Chen, P. Griffin, D. Despommier, and T. A. Brasitus. 1984. Cryptosporidiosis of the human small intestine: a light and electron microscopic study. Hum. Pathol. 15:746-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumadue, J. A., Y. C. Manabe, R. D. Moore, P. C. Belitsos, C. L. Sears, and D. P. Clark. 1998. A clinicopathologic analysis of AIDS-related cryptosporidiosis. AIDS 24:2459-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcial, M. A., and J. L. Madara. 1986. Cryptosporidium: cellular localization, structural analysis of absorptive cell-parasite membrane-membrane interactions in guinea pigs, and suggestion of protozoan transport by M cells. Gastroenterology 90:583-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCole, D. F., L. Eckmann, F. Laurent, and M. F. Kagnoff. 2000. Intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun. 68:1710-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojcius, D. M., J. L. Perfettini, A. Bonnin, and F. Laurent. 1999. Caspase-dependent apoptosis during infection with Cryptosporidium parvum. Microbes Infect. 1:1163-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renehan, A. G., C. Booth, and C. S. Potten. 2001. What is apoptosis, and why is it important? BMJ 322:1536-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenblatt, J., M. C. Raff, and L. P. Cramer. 2001. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Curr. Biol. 11:1847-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi, A., K. Ohnishi, I. Ota, I. Asakawa, T. Tamamoto, Y. Furusawa, H. Matsumoto, and T. Ohnishi. 2001. p53-dependent thermal enhancement of cellular sensitivity in human squamous cell carcinomas in relation to LET. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 77:1043-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi, H., A. Ishida-Yamamoto, and H. Iizuka. 2001. Ultraviolet B irradiation induces apoptosis of keratinocytes by direct activation of Fas antigen. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 6:64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzipori, S., and J. K. Griffiths. 1998. Natural history and biology of Cryptosporidium parvum. Adv. Parasitol. 40:6-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vetterling, J. M., A. Takeuchi, and P. A. Madden. 1971. Ultrastructure of Cryptosporidium wrairi from the guinea pig. J. Protozool. 18:248-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widmer, G., E. A. Corey, B. Stein, J. K. Griffiths, and S. Tzipori. 2000. Host cell apoptosis impairs Cryptosporidium parvum development in vitro. J. Parasitol. 86:922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]