Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni produces a toxin, called cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), which causes direct DNA damage leading to invocation of DNA damage checkpoint pathways. The affected cells arrest in G1 or G2 and eventually die. CDT consists of three protein subunits, CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC, with CdtB recently identified as a nuclease. However, little is known about the functions of CdtA or CdtC. In this work, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based experiments were used to show, for the first time, that both CdtA and CdtC bound with specificity to the surface of HeLa cells, whereas CdtB did not. Varying the order of the addition of subunits for reconstitution of the holotoxin had no effect on activity. In addition, mutants containing deletions of conserved regions of CdtA and CdtC were able to bind to the surface of HeLa cells but were not able to participate in holotoxin assembly. Finally, both Cdt mutant subunits were able to effectively compete with CDT holotoxin in the HeLa cell binding assay.

Campylobacter jejuni is a leading bacterial cause of human diarrheal disease throughout the world (8). The genome of this food-borne pathogen has been sequenced, yet only a few potential virulence factors produced by C. jejuni are known or well characterized (23). One of these is the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), a toxin that causes cell cycle arrest and eventual death in sensitive eukaryotic cells (4, 10, 30, 34). While the contribution of CDT to C. jejuni pathogenesis has not been clearly determined, the fact that CDT acts on a variety of mammalian cells, including T cells (10), and that cdt genes have been found in such diverse bacterial pathogens as Haemophilus ducreyi (3, 4), enterohepatic Helicobacter spp. (35), Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (21, 31, 32), and some Escherichia coli (15, 24, 26, 29) and Shigella spp. (22) isolates suggests that CDT may play a role in disease progression and immunosuppression.

CDT is encoded by three adjacent genes, cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC, and expression of all three cdt genes is required in order to produce active CDT (26, 27). CdtB has been shown to act as a nuclease (7, 13, 17), and two groups have recently shown that CdtB apparently causes double-stranded cuts of host cell DNA (14, 19). While progress in understanding the function of CdtB has been made, there is still little known about the precise roles of CdtA and CdtC in CDT function. Recent evidence indicates that all three Cdt subunits are present in the CDT holotoxin, most likely in a 1:1:1 stoichiometry (18). CdtA shares some similarity in folding structure to the ricin B chain, which is involved in ricin binding and uptake (13, 18), and in addition, C. jejuni CdtA and CdtC share about 40% sequence similarity with each other (28; C. L. Pickett, unpublished data). Mao and DiRienzo (20) recently reported evidence from confocal microscopy suggesting that the CdtA subunit binds to Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, but they did not observe binding of CdtB or CdtC to these cells and they observed very low levels of CDT holotoxin binding. In this work, we used purified C. jejuni Cdt subunits to determine the activity of reconstituted holotoxin and investigated the binding capabilities of holotoxin and individual subunits to HeLa cells. In addition, we identified regions within CdtA and CdtC that appear to be critical for holotoxin formation.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Bacterial strains, media, and cell culture.

C. jejuni 81-176 was isolated from a patient with diarrheal disease and has been previously described (2, 16). E. coli DH5αMCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), the host strain for all plasmid constructs, was grown in L medium at 37°C. E. coli BL21 was grown in 2× yeast-tryptone-ampicillin medium at 37°C and used for expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.). When necessary, these media were supplemented with ampicillin to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. HeLa cells were grown as described previously (26, 27) in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Cellgro, Herndon, Va.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Creation of the CdtA and CdtC mutations.

pTrc18CDT contains the wild-type cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes isolated from C. jejuni strain 81-176 and has been described previously (27). pTrc18ΔA126-168 is a derivative of pTrc18CDT, in which an in-frame deletion was created in cdtA. Similarly, pTrc18ΔC115-136 was derived from pTrc18CDT and contains an in-frame deletion within cdtC. These mutations were made by using the ExSite PCR site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). pTrc18CDT was the template in these constructions. The primers for pTrc18ΔA126-168 were 5′-GCCAAAACCAATACTTGTCTTAATGC-3′ and 5′-AGCTGCTCCGCTAGGGCCTAAAATGG-3′, and the primers for pTrc18ΔC115-136 were 5′-TTGGAATCTGATGAATGTATAG-3′ and 5′-ACCATCTTTTAGATCATCTTGACAAG-3′.

Generation of GST-Cdt fusions.

Amino-terminal GST-Cdt fusions were created for each Cdt subunit and for each mutant. Individual wild-type cdt genes were amplified by PCR with pTrc18CDT as a template, and plasmids pTrc18ΔA126-168 and pTrc18ΔC115-136 were used as templates to amplify the mutated forms of the cdtA and cdtC genes, respectively. The primers used for amplification of cdtA and cdtAΔ126-168 were5′-GGGGCGGTCGACTGTTCTTCTAAATTTGAAAATGTAAATCC-3′ and 5′-GGGGGCGGGCGGCCGCTCATCGTACCTCTCCTTGGCG-3′. cdtB was amplified with 5′-GGGGCGGGTCGACAATTTTAATGTTGGCACTTGG-3′ and 5′-GGGGCGGGCGGCCGCATGTCCTAAAATTTTCTAAAATTTACTGG-3′, and cdtC and cdtCΔ115-136 were amplified with 5′-GGGGCGGTCGACGCAACTCCTACTGGAGATTTGAAAG-3′ and 5′-GGGGCGGGCGGCCGCATCTTATTCTAAAGGGGTAGCAGC-3′. All primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa).

The individually amplified genes were cloned separately into pGEX-6P-3 (Amersham Biosciences). Plasmids encoding fusion constructs were isolated by using the Qiagen (Valencia, Calif.) plasmid midi kit. Appropriate mutation and fusion construction was confirmed by sequence analysis, and expression of the mutant and wild-type fusion proteins was verified by immunoblot analysis with rabbit polyclonal C. jejuni Cdt-subunit-specific antisera. The rabbit anti-CdtA and anti-CdtC antisera were generated from gel-purified His-tagged CdtA and CdtC proteins, respectively (12). The rabbit anti-CdtB antiserum was produced by Animal Pharm Services, Inc. (Healdsburg, Calif.) by using gel-purified His-tagged CdtB protein.

Isolation and purification of recombinant proteins.

The purification procedure for the isolation of Cdt proteins was adapted from Lara-Tejero and Galan (18). Briefly, expression of fusion proteins was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; final concentration of 1 mM) to cultures with an A600 of 0.6 to 0.8. Cells were harvested 2 h after the addition of IPTG. After centrifugation, the pellets were allowed to incubate for 20 min at 25°C in phosphate-buffered saline (1× PBS) containing 200 μg of lysozyme/ml. The cells were then lysed by two sequential passages through a French pressure cell (1,250 lb/in2). GST-CdtB was found primarily in the soluble fraction; thus, this fusion protein was added directly to the glutathione Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) affinity column. However, the other GST fusions were found in inclusion bodies in the insoluble fraction. These insoluble pellets were washed three times with 100 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 3 M urea, and 3% Triton X-100. The final pellet was denatured in solubilization buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) for 1 h at 25°C, and the protein was diluted to 0.1 mg/ml prior to dialysis. The solubilized protein was dialyzed first in refolding buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, and 5 mM dithiothreitol) and subsequently in 1× PBS (pH 7.3), after which the protein was applied to a glutathione Sepharose affinity column. PreScission protease (Amersham Biosciences) was added directly to the columns according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the cleaved Cdt proteins were eluted. The total protein concentration was assayed by a modification of the Lowry-Folin procedure (25). Purified Cdt preparations were quantified by comparison of Cdt protein intensities to a standard curve generated by known amounts of bovine serum albumin (BSA) on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining. The purity of the Cdt subunit preparations was also assessed by gel electrophoresis and Coomassie blue staining. Some preparations contained small amounts of cleaved GST protein; due to the presence of cleaved GST in the purified Cdt subunit preparations, native GST was used as the negative control in all binding assays.

Reconstitution of CDT holotoxin and HeLa cell assay for toxicity.

Reconstitution of the Cdt holotoxin with purified subunits was adapted from Elwell et al. (6). Briefly, individually purified Cdt proteins were added together in 1× PBS, gently mixed, and then incubated at 25°C without agitation for 1 h. The time of reconstitution and the order of the addition of subunits were varied as described for specific experiments. After reconstitution, the holotoxin was immediately tested for CDT activity in a HeLa cell assay.

In this assay, 4 × 104 HeLa cells/ml were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C overnight. Various combinations of potentially reconstituted Cdt proteins were added directly to nonconfluent HeLa cell monolayers. The treated cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C, after which the cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide to determine DNA content as described by Whitehouse et al. (34). All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated at least two times.

Biotinylation of CDT subunits.

Each purified Cdt protein was placed into a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and dialyzed for 4 h at 4°C in 1× PBS (pH 7.4). EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) was added at a molar ratio (biotin to Cdt protein) of 25:1 for CdtA and 50:1 for all other wild-type and mutant Cdt subunits. After addition of the EZ-Link reagent, the subunits were mixed gently and incubated at room temperature for 30 min without agitation. Tris, at a final concentration of 50 mM, was added to quench any free biotin in the protein sample. The proteins were analyzed for biotinylation by affinity blot analysis by using streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Amersham Biosciences) diluted 1:3,000 in Tris-buffered saline.

Detection of Cdt protein binding to cultured cells.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on live cells (CELISA) for detection of Cdt protein binding was used according to the method of Geraghty et al. (11) with some modifications. Briefly, 96-well plates were seeded with 3.5 × 105 HeLa cells/ml and incubated overnight. The medium was then removed, and the cells were washed once with 1× PBS supplemented with 1 mM magnesium chloride and 1 mM calcium chloride (1× PBS-MC). Various concentrations of individual biotinylated Cdt subunits or combinations of biotinylated subunits were mixed with an equal volume of 1× PBS containing 3% BSA (PBS-BSA) and added to the cells. The HeLa cells were incubated at 4°C for 45 min, washed five times with cold 1× PBS-MC, and then fixed for 15 min at 25°C with rocking in 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde. Following fixation, the cells were washed three times with PBS-BSA. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:15,000; Amersham Biosciences) in PBS-BSA was added to the cells, and incubation continued with rocking at 25°C for 30 min. Finally, the cells were washed five times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 followed by the addition of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (T-5525; Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) at a 1:10 dilution in 0.05 M phosphate-citrate buffer (P-4922; Sigma). Absorbance (at 370 nm) was determined at various time points by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader (Versa Max microplate reader; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.). All data shown represent absorbances determined between 20 and 30 min after the addition of the substrate. Data from earlier time points produced essentially the same curves, with identical maximal saturation concentrations, as that shown, except that the total absorbance was lower. Specific experiments varied as explained in Results. All experiments were performed in triplicate a minimum of two times.

RESULTS

Reconstitution of active CDT holotoxin.

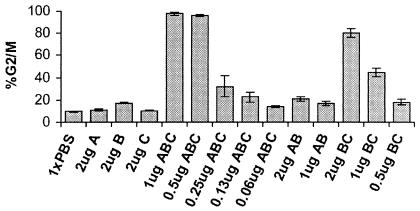

Different combinations of the C. jejuni CDT subunits were combined and tested for reconstitution of CDT holotoxin activity. Titrations were performed to identify the minimum amount of toxin needed to induce cell cycle arrest in HeLa cells. As shown in Fig. 1, CDT treatment of cells for 48 h induced a 95% G2 arrest in HeLa cells when 0.5 μg of each subunit was present. The minimal amount of CDT required to induce G2 arrest consisted of 0.13 μg of each toxin subunit. Each Cdt protein was tested alone, and in agreement with several investigators (1, 9, 18), no activity was seen with individual subunits (Fig. 1). Two subunit combinations were also tested for activity. When CdtA and CdtB were combined, even at the highest concentration, no activity was observed (Fig. 1). However, nearly 80% of the HeLa cells were in G2 after treatment with 2 μg (each) of CdtB and CdtC. Thus, on a per microgram basis, CdtB and CdtC together were about 25% as effective as the CDT holotoxin. These results confirmed that the individually purified C. jejuni Cdt proteins would reconstitute to form a functional holotoxin (18). Additionally, these results indicated that while all three C. jejuni Cdt proteins were required for maximal activity, CdtB and CdtC were able to produce some activity in the absence of CdtA.

FIG. 1.

The effect of Cdt subunit combinations on HeLa cell DNA content. The DNA content of HeLa cells exposed to various combinations of CDT subunits for 48 h was measured, and the percentage of HeLa cells in the G2/M phase is shown. The microgram amounts refer to the amount of each subunit present (e.g., 1 μg ABC means 1 μg of each Cdt subunit). PBS was used as the negative control (1× PBS). In this figure, as in all figures, the mean values and standard deviations are shown for a representative experiment.

Variations in order of addition of Cdt subunits for reconstitution of the holotoxin do not affect activity.

Since all three C. jejuni proteins are apparently required for optimum activity on HeLa cells, we investigated whether the order of Cdt subunit addition in reconstitution reactions affected holotoxin activity. Various combinations of two Cdt subunits were mixed together (0.5 μg of each subunit) and allowed to interact with each other for 45 min. The third Cdt subunit (0.5 μg) was then added to each combination, and incubation continued for an additional 30 min. The reconstituted toxin was added to HeLa cells, and the DNA content of the cells was determined 48 h later. There was no statistically significant difference in the activity observed with these variously reconstituted holotoxins (data not shown). Two positive controls in which all three Cdt subunits were added together at the same time and allowed to reconstitute for 45 or 90 min were included and showed activity comparable to that of the variably reconstituted toxins. These results suggested that there is no specific order of subunit interaction required for the formation of the CDT holotoxin.

Construction of nontoxic CDT mutants.

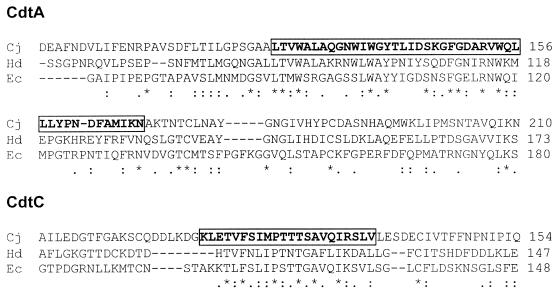

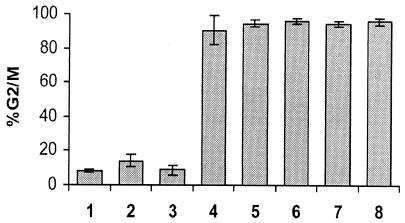

Since it is possible that highly conserved regions within CdtA and CdtC might be important for Cdt function, an in-frame deletion mutant in each subunit was constructed. One mutant, CdtAΔ126-168, consisted of an in-frame deletion of 43 amino acids within CdtA, whereas the other mutant, CdtCΔ115-136, contained an in-frame deletion of 22 amino acids within CdtC. Figure 2 shows a partial alignment of the CdtA and CdtC subunits, highlighting the deleted amino acids. Reconstitution experiments with purified mutant subunits were performed by using 0.5 μg of CdtAΔ126-168 combined with equal amounts of wild-type CdtB and CdtC or 0.5 μg of CdtCΔ115-136 with equal amounts of the wild-type CdtA and CdtB subunits. Neither of the mixtures containing the Cdt mutant subunits (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3) resulted in any significant increase of cells in G2 phase when compared to the PBS control (Fig. 3, lane 1), whereas the wild-type CDT holotoxin caused 90% of the HeLa cells to become blocked in G2 (Fig. 3, lane 4). This result suggested that the Cdt mutant subunits might not be reconstituting with the wild-type Cdt proteins to form an active CDT holotoxin or that the holotoxins containing mutant subunits might not be binding to the HeLa cells. In order to determine if holotoxin reconstitution was occurring, a competitive reconstitution experiment was performed. Two micrograms of each Cdt mutant protein was added to 0.5 μg of the appropriate wild-type Cdt proteins, and the mixtures were allowed to incubate for 45 min to allow reconstitution. This incubation was followed by the addition of 0.5 μg of the wild-type CdtA or CdtC protein to those reactions containing the mutant versions of these subunits, and incubation continued for 30 min. The addition of wild-type CdtA to the CdtAΔ126-168-CdtB-CdtC mixture produced a G2 phase block equivalent to that produced by wild-type CDT holotoxin (Fig. 3, compare lanes 4 and 5). A similar result was seen with the addition of wild-type CdtC to the CdtA-CdtB-CdtCΔ115-136 mutant combination (Fig. 3, lane 6). These results suggested that the Cdt mutants were not able to reconstitute to form an active CDT holotoxin, since if the mutant subunits had assembled into holotoxin, the addition of only 0.5 μg of wild-type CdtA or CdtC would not have been expected to restore full activity, since 0.5 μg is the minimum amount of Cdt subunit shown in Fig. 1 to produce maximal activity. Two controls in which combinations of two Cdt subunits were incubated for 45 min, followed by the addition of the third Cdt subunit and incubation for another 30 min, are shown in Fig. 3 (lanes 7 and 8). In summary, these results suggested that the deleted regions in CdtA and CdtC are involved in interactions between subunits required for formation of the holotoxin.

FIG. 2.

Partial alignment of CdtA and CdtC sequences from three different genera. Cdt proteins from C. jejuni 81-176 (Cj) (27), E. coli 9142-88 (Ec) (26), and H. ducreyi 35,000 (Hd) (3) were aligned to show the conserved regions in both CdtA and CdtC in which the deletions were made. The boxed areas represent the deleted regions. Identical (*), high similarity (:), and low similarity (.) amino acids are indicated. The alignment was performed by using the ClustalW program (33).

FIG. 3.

Lack of holotoxin reconstitution with CdtAΔ126-168 and CdtCΔ115-136 mutants. Reconstituted holotoxin preparations were tested for toxicity by measuring the DNA content of treated HeLa cells. The percentage of HeLa cells in the G2/M phase 48 h after CDT treatment is shown. Bars: 1, 1× PBS; 2, CdtAΔ126-168 and wild-type CdtB and CdtC (0.5 μg of each subunit); 3, CdtCΔ115-136 with wild-type CdtA and CdtB (0.5 μg of each subunit); 4, reconstituted wild-type CDT (0.5 μg of each subunit); 5, competitive reconstitution with 2 μg of CdtAΔ126-168 and 0.5 μg (each) of CdtB and CdtC, followed by addition of 0.5 μg of wild-type CdtA; 6, competitive reconstitution with 2 μg of CdtCΔ115-136 and 0.5 μg (each) of CdtA and CdtB, followed by addition of 0.5 μg of wild-type CdtC; 7, 0.5 μg (each) of CdtA and CdtB, followed by 0.5 μg of CdtC 45 min later; 8, 0.5 μg (each) of CdtB and CdtC, followed by addition of 0.5 μg of CdtA 45 min later.

Binding of Cdt subunits to the HeLa cell surface.

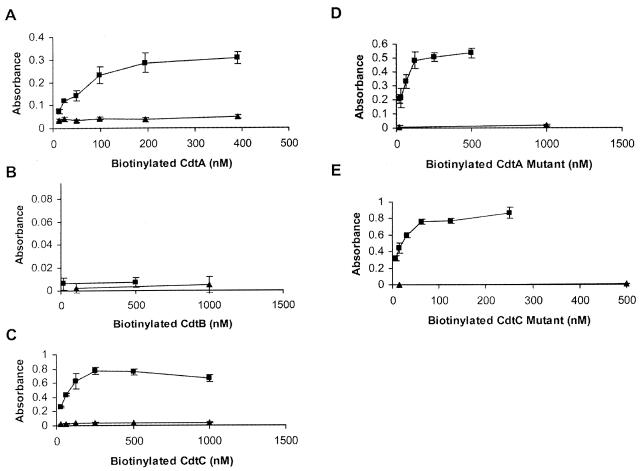

The ability of each Cdt subunit to bind to HeLa cells was quantified in the CELISA test. Each Cdt subunit was biotinylated and tested separately at several different protein concentrations. In Fig. 4A, CdtA binding to HeLa cells was compared to the biotinylated GST control. Binding increased as the CdtA protein concentration increased until saturation was reached at a concentration of approximately 200 nM. CdtB showed no significant binding to the host cell surface (Fig. 4B). The absorbance for CdtB, even at the highest concentration, showed less than a onefold increase when compared to the GST control. CdtC binding was, however, significant (Fig. 4C), reaching saturation at approximately 250 nM (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that both CdtA and CdtC bound individually to the HeLa cell surface but that CdtB did not.

FIG. 4.

Binding of the wild-type and mutant CdtA and CdtC subunits to the surface of HeLa cells. CdtA (panel A, ▪), CdtB (panel B, ▪), CdtC (panel C, ▪), CdtAΔ126-168 (panel D, ▪), and CdtCΔ115-136 (panel E, ▪) were individually biotinylated, added separately to HeLa cell monolayers, and incubated at 4°C for 45 min. Biotinylated GST (▴) was used as the negative control in all five panels, as well as in Fig. 5, 6, 7, and 8.

Binding of Cdt mutant subunits to the HeLa cell surface.

The ability of the individual Cdt mutant subunits to bind to the HeLa cell surface was also tested. The CdtA mutant protein bound to the HeLa cell surface with an efficiency similar to that of the wild-type protein (compare Fig. 4A and D). The CdtC mutant also showed binding to the HeLa cell surface, although the maximum saturation level for the CdtC mutant was approximately 125 nM (Fig. 4E), which is slightly lower than that seen with the wild-type CdtC protein (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that both Cdt mutant subunits were able to bind to the surface of HeLa cells, suggesting that the deleted regions in each Cdt subunit did not play a significant role in cell surface recognition but were instead critical for effective holotoxin formation.

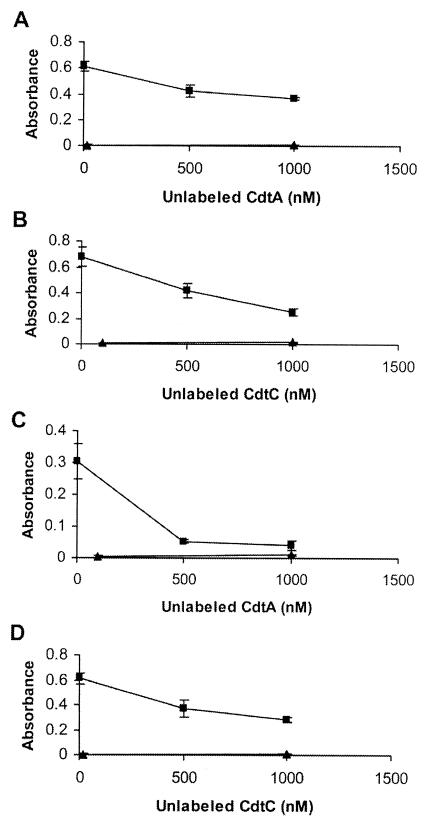

Specificity of binding for wild-type and mutant CdtA and CdtC subunits.

The specificity of wild-type CdtA and CdtC subunit binding was investigated in a competition experiment. Biotinylated CdtA or CdtC was incubated with HeLa cells in the presence of unlabeled CdtA or CdtC subunits, respectively. The biotinylated protein concentration was kept constant while the concentration for unlabeled protein was varied. Binding of biotinylated CdtA decreased almost twofold in the presence of 1,000 nM unlabeled CdtA (Fig. 5A), and there was an approximately threefold decrease in the binding of CdtC-biotin in the presence of 1,000 nM unlabeled CdtC (Fig. 5B). The decreased binding signal from the biotinylated CdtA and CdtC proteins in the presence of unlabeled proteins suggested that the observed association between these two individual Cdt proteins and the HeLa cell surface was specific.

FIG. 5.

Competitive binding of wild-type and mutant CdtA and CdtC subunits to HeLa cells. Biotinylated CdtA (100 nM, panel A, ▪), CdtC (100 nM, panel B, ▪), CdtAΔ126-168 (125 nM, panel C, ▪), and CdtCΔ115-136 (100 nM, panel D, ▪), were added to a HeLa cell monolayer in the absence or presence of 500 or 1,000 nM unlabeled CdtA or CdtC, as noted in the individual panels. ▴, biotinylated GST.

The binding specificity of the CdtAΔ126-168 and CdtCΔ115-136 mutant subunits was tested in the presence of unlabeled wild-type CdtA or CdtC protein, respectively. In Fig. 5C, the binding of the CdtA mutant subunit clearly decreased in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled wild-type CdtA. At the highest concentration of unlabeled CdtA (1,000 nM), there was a fivefold decrease in CdtA mutant binding to the HeLa cell surface. A twofold decrease in binding of the CdtCΔ115-136 mutant subunit was observed in the presence of unlabeled CdtC at 1,000 nM (Fig. 5D). The decrease in binding by the biotinylated CdtA and CdtC mutant proteins in the presence of unlabeled wild-type proteins likely indicated that the mutant subunits bound to the same site on the HeLa cell surface as the wild-type Cdt proteins.

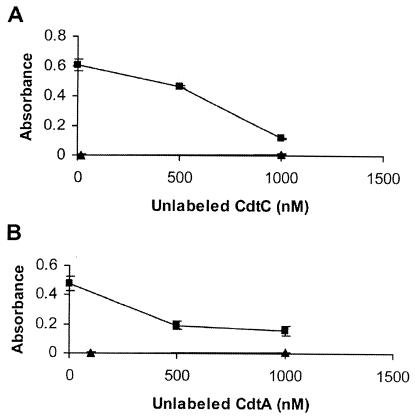

Evidence of competitive binding between CdtA and CdtC.

The binding efficiency of CdtA and CdtC was next tested in the presence of unlabeled CdtC and CdtA, respectively. In this experiment, the binding of biotinylated CdtA (or CdtC) was observed in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled CdtC (or CdtA). As shown in Fig. 6A, biotinylated CdtA binding decreased approximately fivefold in the presence of 1,000 nM unlabeled CdtC. Binding of biotinylated CdtC in the presence of unlabeled CdtA was reduced about threefold (Fig. 6B). These results suggested that CdtA and CdtC were binding to the same receptor on the HeLa cell surface.

FIG. 6.

Competitive binding between CdtA and CdtC. Biotinylated CdtA (panel A, ▪) or CdtC (panel B, ▪), at a constant concentration of 100 nM, was assayed for binding in the absence or presence of 500 or 1,000 nM unlabeled CdtC or CdtA, respectively. ▴, biotinylated GST.

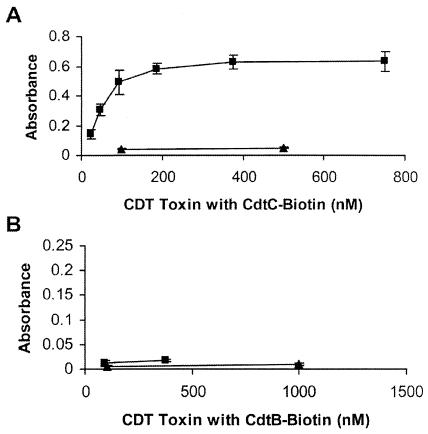

Binding of the CDT holotoxin to HeLa cells.

Binding of the CDT holotoxin was successfully demonstrated by using reconstituted holotoxin consisting of equal molar amounts of unlabeled CdtA and CdtB and biotinylated CdtC. Several different concentrations were tested, and maximal binding was observed at a total toxin protein concentration of 375 nM (125 nM concentration of each subunit) (Fig. 7A). Thus, CDT holotoxin binding to HeLa cells was observed in this assay at levels comparable to that seen with individual Cdt subunits. The detection of holotoxin binding was also attempted with reconstituted toxin containing biotinylated CdtB; however, no signal was observed (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

CDT holotoxin binding to HeLa cells. Reconstituted toxin containing biotinylated CdtC with unlabeled CdtA and CdtB (panel A, ▪) or toxin containing biotinylated CdtB with unlabeled CdtA and CdtC (panel B, ▪) was assayed for binding. ▴, biotinylated GST.

The toxicity of all three biotinylated combinations of reconstituted holotoxin, at a total protein concentration of 21 nM (an approximately 7 nM concentration of each subunit), was assayed on HeLa cells. Reconstituted toxin containing biotinylated CdtB was the most toxic of the biotinylated combinations of holotoxin, causing 32% of the cells to be in the G2 phase within 48 h. Toxin containing biotinylated CdtC was also active on HeLa cells, blocking 22% of HeLa cells in the G2 phase. Equal molar concentrations of unlabeled wild-type holotoxin caused 37% of the cells to be in the G2 phase, indicating that the reconstituted holotoxins containing biotinylated CdtB or CdtC were 70 and 50% as toxic as unlabeled holotoxin, respectively. However, toxin reconstituted with biotinylated CdtA yielded no significant activity upon HeLa cells; 9% of these cells, as well as 9% of the untreated cells, were in the G2 phase (data not shown). This result suggested that the biotinylation of CdtA interfered with subunit-subunit interactions required for holotoxin formation, since biotinylated CdtA alone bound to the cell surface. In summary, biotinylated CdtB and CdtC appeared capable of reconstituting with the other Cdt subunits to form active holotoxin. However, the biotin on CdtB was apparently masked by CdtA and CdtC upon reconstitution and was not accessible for detection in the binding assay. Nonetheless, the toxicity results indicated that both biotinylated forms of the holotoxin (CDT with CdtB-biotin and CDT with CdtC-biotin) must have bound to the HeLa cells, since they were both capable of inducing a significant level of cell cycle arrest.

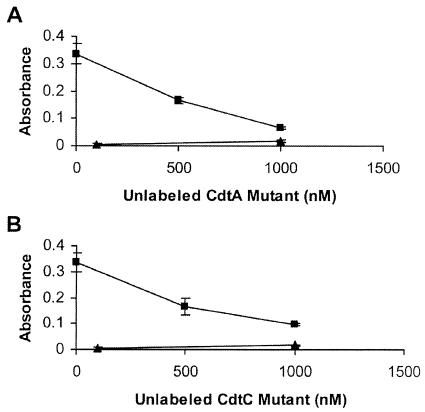

Cdt mutant subunits decrease binding of CDT holotoxin.

Since both Cdt mutant subunits appeared to be binding to the same receptor site on HeLa cells as the wild-type Cdt subunits, a competitive binding between the mutant subunits and the CDT holotoxin was performed. Holotoxin binding was assayed in the presence of increasing amounts of each Cdt mutant subunit. Reconstituted holotoxin containing unlabeled CdtA and CdtB, with biotinylated CdtC present at a total protein concentration of 100 nM (33.3 nM concentration of each Cdt subunit), was tested for HeLa cell binding in the presence of unlabeled CdtAΔ126-168 or CdtCΔ115-136. CDT holotoxin binding decreased nearly fivefold in the presence of the CdtA mutant subunit (Fig. 8A) and almost threefold in the presence of the CdtC mutant subunit (Fig. 8B). These results suggested that both Cdt mutant subunits were capable of blocking the binding of CDT holotoxin to the HeLa cell surface.

FIG. 8.

Competitive binding between CDT holotoxin and the mutant subunits. Reconstituted CDT holotoxin (▪) containing unlabeled CdtA and CdtB with biotinylated CdtC, at a total protein concentration of 100 nM, was assayed for binding in the absence or presence of unlabeled CdtAΔ126-168 (A) or CdtCΔ115-136 (B). ▴, biotinylated GST.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the C. jejuni CDT subunits CdtA and CdtC were both involved in the binding of CDT to sensitive cells. This is the first time evidence has been presented showing that both CdtA and CdtC are capable of binding to target cells. Previous work has shown that CdtB carries the known enzymatic activity of CDT (7, 13, 17), and coupled with this work, it seems reasonable to conclude that CDT is an A:B toxin with the binding function shared between CdtA and CdtC. Our data also indicated that the binding of CdtA and CdtC was specific and that the binding of each was saturable to similar levels. Both CdtA and CdtC binding were decreased in the presence of either CdtC or CdtA. The competitive, unlabeled subunit in these experiments did not completely inhibit the binding of the labeled subunit, but we used only a 10-fold excess of unlabeled inhibitor and both labeled and unlabeled subunits were added simultaneously to sensitive cells. These experimental conditions make it unlikely that complete inhibition by the unlabeled inhibitor would be achieved. In any case, these competition experiments suggested that both Cdt proteins bound to the same receptor on the HeLa cell surface. This is not necessarily surprising given that investigators have noted that CdtA and CdtC share a significant level of primary sequence homology (28; Pickett, unpublished).

Our toxicity data with reconstituted holotoxin supported the findings of Akifusa et al. (1) and Deng et al. (5), who showed that CdtB and CdtC of A. actinomycetemcomitans and H. ducreyi are capable of producing a G2 arrest in the absence of CdtA. This is in contrast to the data of Lara-Tejero and Galan (18), who stated that their C. jejuni CDT showed no activity unless all three subunits were present. We tested toxicity at several concentrations and found that CdtB and CdtC combined could produce arrest but that they did so at only about 25% of the level seen by a comparable amount of holotoxin containing all three subunits. These data further supported the notions that both CdtA and CdtC are involved in binding and that both are needed for maximal efficiency of intoxication.

However, our data differed from the results of Mao and DiRienzo (20) on the binding of CdtA to sensitive cells. In this previous work, the binding of His-tagged Cdt proteins was examined by confocal microscopy. CdtA was observed to be binding to CHO cells, but no evidence for CdtC binding was shown. These authors were also unable to show a significant level of CDT holotoxin binding. In our work, we showed that holotoxin binding could be observed depending upon which subunit was labeled. When biotinylated CdtC was present in reconstituted holotoxin, binding of the holotoxin to HeLa cells was clearly observed. However, when biotinylated CdtB was used in the reconstituted holotoxin, binding was not detected. Since it is clear that in both cases successful reconstitution was achieved, as evidenced by the level of toxicity exhibited by these two reconstituted toxins, it seems logical to infer that the lack of detection of binding by the holotoxin containing biotinylated CdtB was due to the masking of the biotin by the CdtA and CdtC subunits.

Reconstitution experiments using biotinylated CdtA failed. That is, activity could not be detected by using this reconstituted toxin. The inability of biotinylated CdtA to participate in holotoxin reconstitution may explain this result, but it is also possible that holotoxin was formed that was unable to bind and/or be internalized or that, once internalized, the toxin was unable to traffic properly to its target. Elucidation of these alternatives awaits further experimentation.

An examination of the CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC families reveals that each Cdt subunit family contains varied levels of homology (28; Pickett, unpublished), that is, CdtB proteins are the most highly conserved and the CdtC proteins are the least conserved. Within CdtA and CdtC, however, the highest homologies are found in distinct regions of these proteins. We made a deletion in one such region in CdtA and in the region of highest homology within CdtC. These Cdt subunit mutants were tested for their abilities to interact with the other subunits to form holotoxin and for their abilities to bind to HeLa cells. Our results clearly suggested that these regions of homology were involved in subunit-subunit interactions and were not involved in binding to sensitive cells. This may mean that the CDTs produced by different bacterial genera, which have greater variation in portions of CdtA and CdtC, may not necessarily bind to exactly the same receptors, an important consideration for our understanding of the role of CDT in the pathogenesis of the different diseases caused by CDT-producing bacteria.

Finally, our results indicate that our CDT subunit mutants are capable of interfering with CDT holotoxin binding. We are continuing our characterization of these and other mutants in studies designed to determine whether mutant subunits that can bind but are not internalized could be created. Such mutants may be of great importance in developing therapeutic agents capable of interfering with CDT's actions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert J. Geraghty and his lab for discussion and assistance in the development of the CELISA experiments. We also thank Gregory Bauman and Jennifer Strange of the University of Kentucky Flow Cytometry Core Facility.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant no. AI48590 to C.L.P.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Akifusa, S., S. Poole, J. Lewthwaite, B. Henderson, and S. P. Nair. 2001. Recombinant Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin proteins are required to interact to inhibit human cell cycle progression and to stimulate human leukocyte cytokine synthesis. Infect. Immun. 69:5925-5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, R. E., M. M. Levine, M. L. Clements, T. P. Hughes, and M. J. Blaser. 1988. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 157:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cope, L. D., S. Lumbley, J. L. Latimer, J. Klesney-Tait, M. K. Stevens, L. S. Johnson, M. Purven, R. S. Munson, Jr., T. Lagergard, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4056-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes-Bratti, X., E. Chaves-Olarte, T. Lagergård, and M. Thelestam. 1999. The cytolethal distending toxin from the chancroid bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi induces cell-cycle arrest in the G2 phase. J. Clin. Investig. 103:107-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng, K., J. L. Latimer, D. A. Lewis, and E. J. Hansen. 2001. Investigation of the interaction among the components of the cytolethal distending toxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285:609-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwell, C., K. Chao, K. Patel, and L. Dreyfus. 2001. Escherichia coli CdtB mediates cytolethal distending toxin cell cycle arrest. Infect. Immun. 69:3418-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwell, C. A., and L. A. Dreyfus. 2000. DNase I homologous residues in CdtB are critical for cytolethal distending toxin-mediated cell cycle arrest. Mol. Microbiol. 37:952-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman, C. R., J. Neimann, H. C. Wegener, and R. V. Tauxe. 2000. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Frisk, A., M. Lebens, C. Johansson, H. Ahmed, L. Svensson, K. Ahlman, and T. Lagergard. 2001. The role of different protein components from the Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin in the generation of cell toxicity. Microb. Pathog. 30:313-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelfanova, V., E. J. Hansen, and S. M. Spinola. 1999. Cytolethal distending toxin of Haemophilus ducreyi induces apoptotic death of Jurkat T cells. Infect. Immun. 67:6394-6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geraghty, R. J., C. R. Jogger, and P. G. Spear. 2000. Cellular expression of alphaherpesvirus gD interferes with entry of homologous and heterologous alphaherpesviruses by blocking access to a shared gD receptor. Virology 268:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 13.Hassane, D. C., R. B. Lee, M. D. Mendenhall, and C. L. Pickett. 2001. Cytolethal distending toxin demonstrates genotoxic activity in a yeast model. Infect. Immun. 69:5752-5759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassane, D. C., R. B. Lee, and C. L. Pickett. 2003. Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin promotes DNA repair responses in normal human cells. Infect. Immun. 71:541-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, W. M., and H. Lior. 1988. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Escherichia coli isolates from clinical material. Microb. Pathog. 4:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korlath, J. A., M. T. Osterholm, L. A. Judy, J. C. Forfang, and R. A. Robinson. 1985. A point-source outbreak of campylobacteriosis associated with consumption of raw milk. J. Infect. Dis. 152:592-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galán. 2000. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein. Science 290:354-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galán. 2001. CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC form a tripartite complex that is required for cytolethal distending toxin activity. Infect. Immun. 69:4358-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, L., A. Sharipo, E. Chaves-Olarte, M. G. Masucci, V. Levitsky, M. Thelestam, and T. Frisan. 2002. The Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin activates sensors of DNA damage and repair complexes in proliferating and non-proliferating cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao, X., and J. M. DiRienzo. 2002. Functional studies of the recombinant subunits of a cytolethal distending holotoxin. Cell. Microbiol. 4:245-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer, M. P., L. C. Bueno, E. J. Hansen, and J. M. DiRienzo. 1999. Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 67:1227-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda, J., H. Kurazono, and Y. Takeda. 1995. Distribution of the cytolethal distending toxin A gene (cdtA) among species of Shigella and Vibrio, and cloning and sequencing of the cdt gene from Shigella dysenteriae. Microb. Pathog. 18:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkhill, J., B. W. Wren, K. Mungall, J. M. Ketley, C. Churcher, D. Basham, T. Chillingworth, R. M. Davies, T. Feltwell, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. V. Karlyshev, S. Moule, M. J. Pallen, C. W. Penn, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, A. H. van Vliet, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2000. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403:665-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérès, S. Y., O. Marches, F. Daigle, J. P. Nougayrede, F. Herault, C. Tasca, J. De Rycke, and E. Oswald. 1997. A new cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) from Escherichia coli producing CNF2 blocks HeLa cell division in G2/M phase. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1095-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson, G. L. 1977. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal. Biochem. 83:346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pickett, C. L., D. L. Cottle, E. C. Pesci, and G. Bikah. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect. Immun. 62:1046-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickett, C. L., E. C. Pesci, D. L. Cottle, G. Russell, A. N. Erdem, and H. Zeytin. 1996. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp.cdtB gene. Infect. Immun. 64:2070-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickett, C. L., and C. A. Whitehouse. 1999. The cytolethal distending toxin family. Trends Microbiol. 7:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott, D. A., and J. B. Kaper. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 62:244-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sert, V., C. Cans, C. Tasca, L. Bret-Bennis, E. Oswald, B. Ducommun, and J. De Rycke. 1999. The bacterial cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) triggers a G2 cell cycle checkpoint in mammalian cells without preliminary induction of DNA strand breaks. Oncogene 18:6296-6304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenker, B. J., R. H. Hoffmaster, T. L. McKay, and D. R. Demuth. 2000. Expression of the cytolethal distending toxin (Cdt) operon in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: evidence that the CdtB protein is responsible for G2 arrest of the cell cycle in human T cells. J. Immunol. 165:2612-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugai, M., T. Kawamoto, S. Y. Pérès, Y. Ueno, H. Komatsuzawa, T. Fujiwara, H. Kurihara, H. Suginaka, and E. Oswald. 1998. The cell cycle-specific growth-inhibitory factor produced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 66:5008-5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehouse, C. A., P. B. Balbo, E. C. Pesci, D. L. Cottle, P. M. Mirabito, and C. L. Pickett. 1998. Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin causes a G2-phase cell cycle block. Infect. Immun. 66:1934-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young, V. B., K. A. Knox, and D. B. Schauer. 2000. Cytolethal distending toxin sequence and activity in the enterohepatic pathogen Helicobacter hepaticus. Infect. Immun. 68:184-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]