Abstract

Inflammation is a prominent feature of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in both humans and animal models. Indeed, an intense host immune response to infection is thought to contribute significantly to the pathology of pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis. Previously, induction of the inflammatory response following infection with S. pneumoniae has been attributed to certain cell wall constituents and the toxin pneumolysin. Here we present data implicating a putative zinc metalloprotease, ZmpB, as having a role in inflammation. Null mutations were created in the zmpB gene of the virulent serotype 2 strain D39 and analyzed in a murine model of infection. Isogenic mutants were attenuated in pneumonia and septicemia models of infection, as determined by levels of bacteremia and murine survival. Mutants were not attenuated in colonization of murine airways or lung tissue. Examination of cytokine profiles within the lung tissue revealed significantly lower levels of the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha following challenge with the ΔzmpB mutant (Δ739). These data identify ZmpB as a novel virulence factor capable of inducing inflammation in the lower respiratory tract. The possibility that ZmpB was involved in inhibition of complement activity was examined, but the data indicated that ZmpB does not have a significant effect on this important host defense. The regulation of ZmpB by a two-component system (TCS09) located immediately upstream of the zmpB gene was examined. TCS09 was not required for the expression of zmpB during exponential growth in vitro.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a human pathogen responsible for potentially serious infections such as pneumonia, septicemia, and meningitis. The pathology of pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis is thought to result from an exaggerated host inflammatory response to bacterial components (56). Overwhelming inflammation contributes to tissue injury and shock. This is supported by the observation that death may occur days after the initiation of antibiotic therapy, when tissue is sterile (2, 6). The inflammatory response to pneumococcal pneumonia is complex and involves a range of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, the balance of which is crucial in determining the outcome of infection. In microbial infection, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a well-established early mediator of this inflammation, and its production is crucial for the ability of the host to control such infections (3, 28, 50). Many groups have identified a protective role for TNF-α in pneumococcal infection in vivo (26, 38, 53). However, TNF-α can also be detrimental by inducing tissue injury within the lung. Such injury could impair tissue integrity and enhance dissemination of bacteria from the lungs to the bloodstream (2).

The ability of the pneumococcal cell wall and the toxin pneumolysin to induce inflammation has been identified in previous studies (8, 19, 46), but little is known about other bacterial factors that could influence the inflammatory response. We have identified a putative zinc metalloprotease, ZmpB, as having a role in inducing inflammation within the lower respiratory tracts of infected mice. The gene encoding this putative protease in the TIGR4 strain is 5.65 kb and codes for 1,800 amino acids with a molecular mass of ca. 210 kDa. The zmpB gene is located downstream of a two-component signal transduction system, TCS09. Although this system has previously been designated ZmpS/ZmpR, for the histidine kinase sensor and response regulator protein, respectively (14, 37) (see references 51 and 52 for reviews of bacterial two-component signal transduction systems) no evidence to date, including the data presented in this paper, has provided a direct link between this two-component system and ZmpB expression. Thus, we recommend using the original designation, TCS09 (27), when referring to this two-component system.

The ZmpB protein was originally identified in a search for putative adhesion molecules and was designated ZmpB (37). It was characterized as a putative zinc metalloprotease based on an HEXXH-E motif that is conserved in all other zinc metalloproteases (45). S. pneumoniae ZmpB has been detected in several genome-wide approaches for identifying potential pneumococcal virulence factors. Such approaches have included differential fluorescence induction to identify genes that are up-regulated in vivo (31), two signature-tagged mutagenesis screens (14, 44, 54), and searches based on known cell surface anchoring motifs (61; S. Koenig, personal communication). However, the role of ZmpB in virulence has not been investigated in any detail.

zmpB is one of few pneumococcal genes that displays extensive sequence variation between serotypes (1). This suggests that the ZmpB protein could be important in human infection and that there is immune pressure from the host against ZmpB. Within the ZmpB protein sequence, the first 300 to 400 amino acids, at the N-terminal region of the protein, show ca. 99% homology between all pneumococcal serotypes examined. This region contains a potential signal peptidase site, followed by two hydrophobic regions of alpha helices and an LPXTG motif (1). The remainder of the protein is highly variable, with the TIGR4 (serotype 4) strain showing 40 and 41% identity with the R6 (serotype 2) and G54 (serotype 19F) sequences, respectively. The G54 and R6 sequences are more closely related but still only show 67% identity within the variable region. Although the HEXXH-E motif is situated within the variable region, this motif is conserved between serotypes for which sequence data are available, suggesting a functional significance.

The LPXTG motif present in ZmpB is often found in proteins of gram-positive bacteria, where it serves to act as a cell surface anchor through the action of sortase enzymes (40). However, the LPXTG motif is usually found near the C-terminal ends of bacterial proteins (32). As the LPXTG motif lies near the N-terminal region of ZmpB, it is not known if it serves as a true cell surface anchor. According to the biochemistry of the sortase enzymes, the LPXTG motif would serve to anchor only the small N-terminal region prior to this motif (32). The cellular location of ZmpB is thus unknown and requires further investigation.

The ZmpB proteins of the sequenced S. pneumoniae strains (TIGR4 and R6) both show homology with IgA1 proteases (iga products) from S. pneumoniae and other bacteria, mainly streptococcal species. These proteases function to cleave IgA1 and are thus thought to function in immune evasion (43). A region near the N terminus of ZmpB also shows some homology to Hic (also known as PspC, CbpA, and SpsA [11, 12, 20]). This pneumococcal protein has been shown to bind to factor H, a host protein involved in regulation of the complement cascade (21, 22, 36). It is thought that binding of factor H to the pneumococcal cell surface may prevent complement deposition and subsequent opsonophagocytosis and bacterial killing (22, 48). Hic has also been demonstrated to induce interleukin-8 production and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 from human lung epithelial cells, and it thus may contribute to the inflammation seen in pneumococcal pneumonia (30, 35).

Previously, there was some controversy about the various in vitro phenotypes attributed to isogenic zmpB mutations (1, 37), but this has been resolved (1) and the function of ZmpB still remains to be determined. The main aim of this work was thus to examine the role of ZmpB in the virulence of S. pneumoniae by using a murine model of infection. Preliminary experiments were first conducted to confirm that the in vitro phenotype caused by the ΔzmpB mutation in strain D39 (Δ739) did not differ from that described previously with pneumococcal strains R6 and TIGR4 (1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pneumococcal strains.

Mutations were created in the unencapsulated S. pneumoniae strain R800 (1) (see below) and transferred into strain D39 (encapsulated, serotype 2, NCTC 7466) for all virulence studies. S. pneumoniae strains were maintained in brain heart infusion broth (BHI) (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) or on blood agar base 2 (BAB) (Oxoid Ltd.) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) defibrinated horse blood (E&O Laboratories, Bonnybridge, United Kingdom). For culture of mutants, medium or agar was supplemented with 200 μg of spectinomycin ml−1. All strains were confirmed as being S. pneumoniae by Gram staining, optochin sensitivity, presence of α-hemolysis on BAB plates, and multilocus sequence typing. The Quellung reaction was used to confirm the capsular serotype.

Construction of mutants.

A series of mutations in the zmpB gene in strain R800 were created by mariner mutagenesis as described previously (1) and transferred into D39 by transformation. PCR with primers ZmpBUp and ZmpBDo, flanking the entire zmpB gene (1), was used to isolate one of the mariner mutants. The resulting PCR fragment was used to transform strain D39 as described below to create an isogenic zmpB mutant. Mutants were selected on spectinomycin, due to the insertion of the mariner cassette. Chromosomal DNA was prepared and mutants were confirmed by using PCR, as described previously (1).

The zmpB gene corresponds to Sp0664 of the published TIGR4 sequence and Spr0581 of the published R6 sequence (GenBank accession numbers AE005672 and NC 003098, respectively).

Transformation of S. pneumoniae.

Cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in BHI supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2 (final concentration). One milliliter of culture was incubated with competence-stimulating peptide (CSP-1) (15), at a final concentration of 100 ng ml−1, at 37°C for 15 min. Sample DNA (8 to 10 μg) was added, and cultures were incubated for 75 min at 37°C. Potential transformants were selected by their ability to grow on BAB supplemented with spectinomycin (200 μg ml−1). As a control, D39 was transformed with plasmid pVA838, which is able to replicate in the pneumococcus and confers erythromycin resistance on transformants (29). To determine the transformation efficiencies of strains, the transformation procedure was carried out with pVA838, as described above. The transformation mix was plated out on BAB both with and without antibiotic (erythromycin, 1 μg ml−1) for enumeration of viable cells. Efficiency was calculated based on number of transformants per microgram of genomic DNA.

Preparation of S. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA.

Cultures at mid-log phase were centrifuged for 15 min at 5,087 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of extraction buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1, and the mixture was incubated for 3 h at 50°C. RNase (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg ml−1 and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The resultant suspension was mixed with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol) and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. The aqueous layer was added to 0.2 volume of 10 M ammonium acetate. Ethanol (100%) was added to precipitate the DNA, and the mixture was centrifuged at 17,900 × g for 30 min. The DNA pellet was left to air dry for 10 min and resuspended in DNase-free Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 7.4.

Preparation of bacterial RNA.

Bacterial RNA was isolated by using a commercially available kit (Rneasy minikit; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were carried out by using the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Prior to use, RNA was treated with DNase (RQ1; Promega) according to manufacturer's specifications. cDNA synthesis with random hexamers was performed by using the recommended ThermoScript RT-PCR system protocol. Control reactions were performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. The resulting cDNA was treated with 1 μl of Escherichia coli RNase H (2 U μl−1; Invitrogen Life Technologies) at 37°C for 20 min and stored at −20°C until required. PCRs were performed with 2 μl of the cDNA from the RT reaction. Negative control reactions were set up by using cDNA synthesis reactions carried out in the absence of reverse transcriptase and in the absence of template DNA. A genomic DNA PCR was included as a positive control. Detection of 16S RNA was also included as a positive control. Primers used for RT-PCR were ZmpF1 (5′-3′, GTAGTTCGGATGACACA), ZmpR1 (5′-3′, TTGAGGTGCTTGGAGAAC), 16SF (5′-3′, GATAACTATTGGAAACGATAGCTAATACCG), and 16SR (5′-3′, GCTAATGCGTTAGCTACGGCACTAAACCC).

In vitro growth and stability.

Fifteen milliliters of BHI was inoculated with 106 CFU of bacteria and incubated at 37°C. The OD600 was determined, and viable cells enumerated at predetermined time points as described previously (7). To assess the ability of mutant strains to retain spectinomycin resistance, cultures were grown in the absence of antibiotic. At predetermined time points, viability in the presence and absence of spectinomycin was determined.

Cell morphology.

Gram staining and microscopic examination of bacterial cultures grown in BHI were used to determine cell morphology.

Lysis with DOC.

Fifteen milliliters of BHI, without antibiotic selection, was inoculated with 106 CFU of bacteria. Cultures were incubated at 37°C until mid-log phase (OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6) was reached. A 10% (wt/vol) solution of deoxycholate (DOC) (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to 5-ml aliquots of each culture at a final concentration of 0.04% (wt/vol). Samples were removed for enumeration of viable cells immediately prior to and following treatment with DOC at predetermined time points for up to 60 min. An untreated culture was used as a control.

Hemolytic assay.

Cultures were grown to mid-log phase. Samples were removed and treated for 5 min with a 0.04% final concentration of DOC (Sigma-Aldrich) to lyse all cells and release hemolysins. Lysed cultures were diluted 1:2 across a 96-well round-bottom plate in PBS in a final volume of 50 μl. Control wells contained PBS alone, cultures of a Δpln mutant (a pneumolysin null mutant created by allelic replacement in our laboratory [unpublished data]), BHI with 0.04% DOC, and non-DOC-lysed bacterial cultures. Fifty microliters of a 2% (wt/vol) suspension of sheep red blood cells (E&O Laboratories) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and at room temperature for 30 min. Hemolysis of sheep red blood cells was assessed visually by the absence of a compact pellet following incubation.

Mice.

Female outbred MF1 mice (Harlan Olac, Bicester, United Kingdom), age 9 to 13 weeks and weighing 30 to 35 g, were used as the model for pneumococcal pneumonia and sepsis. Complement studies were carried out with 9- to 13-week-old C3−/− mice on a C57BL background (60). Age- and sex-matched C57BL mice (Harlan Olac) were used as wild-type controls for the experiments with C3−/− mice. All mice were provided with sterile pelleted food (B&K Universal, North Humberside, United Kingdom) and water ad libitum. All animal work was carried out under appropriate licensing and with approval from the Home Office and the University of Glasgow.

Preparation of standard inoculum.

Prior to use in mice, all strains were passaged by intraperitoneal injection as described previously (7). Aliquots of bacteria were stored at −70°C. When required, aliquots were thawed rapidly, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in sterile PBS.

Determination of end points.

Mice were monitored frequently for symptoms of infection, which progressed from piloerection and a hunched stance to severe lethargy. For analysis of survival data, mice were sacrificed upon reaching a state of severe lethargy or when moribund. The death of infected mice was not used as an end point. Mice that survived the course of infection (7 days, unless stated otherwise) were assigned an arbitrary survival time of 168 h for statistical analysis.

Intranasal infection of mice.

Mice were lightly anesthetized with 2.5% (vol/vol) Halothane (Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Macclesfield, United Kingdom), and 106 CFU of bacteria resuspended in sterile PBS was administered into the nares in a total volume of 50 μl. The inoculum dose was confirmed by plating on BAB as described above. At predetermined time points a small volume of blood was removed from a tail vein with a 1-ml insulin syringe (Micro-fine, 12.7 mm; Becton Dickinson), and bacteremia was determined by enumeration of viable cells. Symptoms were monitored for 168 h postinfection, and mice were culled prior to or upon reaching a moribund state.

Intravenous infection of mice.

Groups of mice were each given 105 CFU of bacteria resuspended in sterile PBS, administered directly into a tail vein. At predetermined time points a small volume of blood was removed from a tail vein with a 1-ml insulin syringe, and bacteremia was determined by enumeration of viable cells. Symptoms were monitored for 168 h postinfection, and mice were culled prior to or upon reaching a moribund state.

Enumeration of bacteria in lung tissue.

Following intranasal challenge with 106 CFU as described above, mice were sacrificed at predetermined time points by cervical dislocation. Lungs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 5 ml of sterile PBS by using an electric tissue homogenizer. Bacterial counts in lung tissue were determined by enumeration of viable cells.

Preparation of lung tissue for cytokine analysis.

At predetermined time points following intranasal challenge, mice were culled by cervical dislocation and the thoracic cavity was opened to expose the lungs. Lungs were aseptically removed, wrapped in aluminum foil, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Prior to use, lungs were weighed and homogenized. Based on the protocol of van der Poll et al. (57), homogenates were centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 30 min at 4°C (Sigma 4K15 centrifuge) to pellet cell debris. The supernatants were then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and filter sterilized through 0.20-μm-pore-size filters (Sartorius Ag, Göttingen, Germany). The cell-free supernatant was aliquoted into cryovials and stored at −70°C until required.

Bronchialveolar lavage for bacteriology and cytokine analysis.

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The skin and muscles surrounding the trachea were exposed, and the thoracic cavity was opened to allow expansion of the lungs. The trachea was clamped with forceps to prevent backflow of fluid up the trachea. A 16-gauge nonpyrogenic angiocath (F. Baker Scientific, Runcorn, United Kingdom) was inserted into the trachea immediately above a ring of cartilage to hold the catheter in place. Lavage was performed with two 1-ml volumes of PBS. A small aliquot of bronchialveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was retained for enumeration of viable cells, and the remainder was snap frozen in liquid N2 in cryovials. BALF was stored at −70°C until required.

Cytokine analysis.

TNF-α was detected with the OptEIA mouse TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

All results are presented as geometric means ± 1 standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed by using Student's two-sample t test and Mann-Whitney U tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a P value of <0.005 was considered highly significant. For all animal work a minimum of five animals per strain were evaluated for each time point.

RESULTS

Creation and confirmation of mutants.

A series of interruptions along the zmpB gene were created by using mariner mutagenesis (1). Mutations were originally made in S. pneumoniae strain R800, an unencapsulated, avirulent derivative of D39. PCR products from two independent R6 zmpB integration mutants (the Δ738 and Δ739 mutants) were used to transform the virulent type 2 pneumococcal strain D39, resulting in truncations at 1.5 and 0.6 kb relative to the start of the zmpB gene, respectively. Potential transformants were selected on spectinomycin plates and confirmed by PCR. The insertion of the mariner cassette into the zmpB gene was confirmed by using primers ZmpBUp, ZmpBDo, and MP128, as described previously (1). As the mutations behaved similarly in all in vivo experiments, only data for the more truncated Δ739 mutant are presented.

Growth and stability in vitro.

No difference in growth was observed for the mutant compared to the D39 parental strain, as measured by enumeration of viable cells or by OD (data not shown). Comparison of the Δ739 mutant grown in the presence and absence of spectinomycin indicated that the antibiotic did not adversely affect growth (data not shown). The mutants were also shown to be stable during in vitro growth in the absence of spectinomycin (data not shown).

Expression of zmpB in vitro.

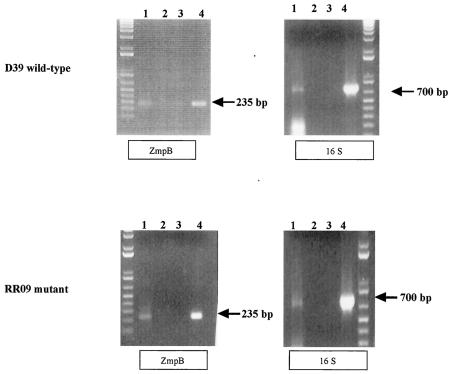

RT-PCR was used to determine if zmpB is expressed by D39 during in vitro growth. RNA was isolated from wild-type D39 grown in BHI to mid-exponential phase. RT-PCR analysis was performed with two independent D39 RNA preparations. Expression of zmpB in D39 could be detected during in vitro growth by using this technique (Fig. 1, top panels). To determine if zmpB expression is regulated by the two-component signal transduction system immediately upstream of the zmpB locus, RT-PCR was performed, as described above, with an isogenic strain with a null mutation in the response regulator gene (Δrr09) (3a). zmpB transcript was detected during in vitro growth of the Δrr09 mutant (Fig. 1, bottom panels), indicating that the two-component system is not required for zmpB expression under these conditions.

FIG. 1.

Regulation of zmpB by TCS09. RNA isolated from cells grown to mid-log phase was used to determine the presence of zmpB transcript in the Δrr09 mutant (bottom panels) compared to the wild-type D39 strain (top panels) during in vitro growth. Primers ZmpIntF1 and ZmpIntR1 produced an expected band size of 235 bp. Primers 16SF and 16SR, specific for 16S RNA, were used as a positive control for RNA detection and resulted in a band of 700 bp. Lanes for all gels: 1, cDNA template from wild-type D39 (top panels) or the Δrr09 mutant (bottom panels); 2, cDNA template prepared in the absence of reverse transcriptase; 3, no DNA template; 4, genomic DNA template. A band of the expected size was observed in lanes 1 and 4 only with zmpB primers and the 16S primers with both wild-type D39 and mutant Δrr09 cDNAs. No bands were observed for the negative controls (lanes 2 and 3).

Cell morphology and autolysis with DOC.

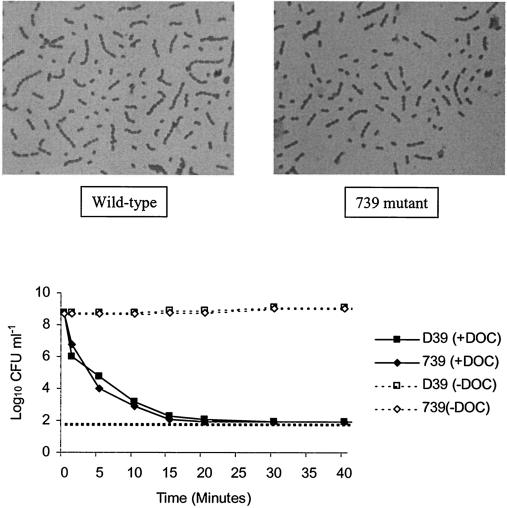

Microscopic examination by Gram staining was used to examine cell morphology during in vitro growth. The Δ739 mutant was found to grow in pairs or short chains indistinguishable from wild-type D39 cells (Fig. 2, top panels). Cultures at different stages of growth were examined to determine if chain formation was specific to a certain phase of growth, but no differences were detected (data not shown), suggesting that the mutant strain was able to undergo normal separation of daughter cells. Growth data indicated that the Δ739 mutant is able to autolyse following entry into stationary phase during in vitro culture (data not shown), demonstrating that the mutant has a functional LytA enzyme, which is required for pneumococcal lysis (55). To further confirm the presence of active LytA, the effect of DOC (an allosteric activator of LytA) on the viability of cultures was determined. Following addition of DOC to bacterial cultures grown to mid-exponential phase, a rapid reduction in viable cell counts was observed for both D39 and the Δ739 mutant, with viable counts being below the detection limit at 15 min after DOC treatment (Fig. 2, bottom panel). This provides further evidence that the LytA enzyme responsible for autolysis is fully functional in the Δ739 mutant.

FIG. 2.

Cell morphology and autolysis. (Top panels) Cell morphology. Bacterial strains were grown in BHI and examined microscopically at various stages of growth. Gram staining revealed gram-positive cocci which occurred singly, in pairs, and in short chains for both the wild-type and Δ739 mutant strains. Samples examined at the mid-exponential phase of growth are shown. No difference in cell morphology was observed at other stages of growth. (Bottom panel) Autolysis with DOC. D39 and Δ739 cultures were grown to mid-log phase in BHI. Each culture was divided into two equal volumes, and DOC (0.04% final concentration) was added to an aliquot of each strain. Untreated aliquots of cultures were used as controls. Viability counts for all cultures were performed at predetermined intervals for 60 min after DOC treatment. The horizontal broken line represents the lower limit of detection.

Transformation efficiency of the Δ739 mutant.

To assess the ability of the Δ739 mutant to take up DNA from the surrounding environment, bacterial strains were transformed with pVA838, a plasmid conferring erythromycin resistance with the ability to replicate in S. pneumoniae (29). The number of transformants obtained for the Δ739 mutant was comparable to those obtained for the D39 parent (data not shown). This suggests that the mutant is not impaired in its ability to acquire DNA from the external environment compared to the isogenic wild-type strain, as determined previously (1).

Hemolytic activity.

D39 and the Δ739 mutant were characterized for their ability to induce lysis of sheep red blood cells. Hemolysis was not observed with any of the negative controls, including a pneumolysin null (Δpln) mutant treated with DOC, indicating that any lysis observed was largely due to pneumolysin and not other pneumococcal hemolysins. All DOC-lysed cultures (with the exception of the Δpln mutant) showed complete hemolysis of sheep red blood cells up to a 1:8 dilution (data not shown). These data indicate that the Δ739 mutant expresses amounts of active pneumolysin similar to those expressed by the D39 wild-type strain during in vitro growth.

Intranasal challenge. (i) Survival and bacteremia.

Prior to all subsequent in vivo work, bacterial strains were mouse passaged by intraperitoneal injection.

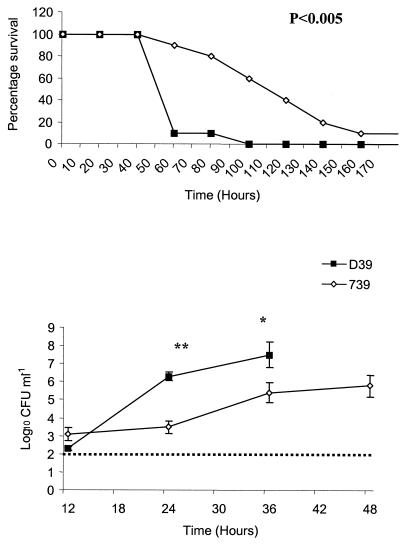

Strains were analyzed for their ability to induce disease in a murine infection model of pneumonia. Outbred MF1 mice were given 106 CFU intranasally and monitored for their ability to survive infection. All mice challenged with wild-type D39 succumbed to infection within 100 h following challenge, with a median survival time of 45 h. Although 90% of mice challenged with the Δ739 mutant succumbed to infection, the progression was much slower than that of wild-type infection, with a median survival time of 127 h, nearly threefold longer than survival following D39 challenge (P < 0.005). Indeed, at 60 h postinfection only 1 of 10 mice challenged with D39 had survived the challenge, but 9 of 10 mice infected with the Δ739 mutant remained healthy and did not show any signs of infection (Fig. 3).

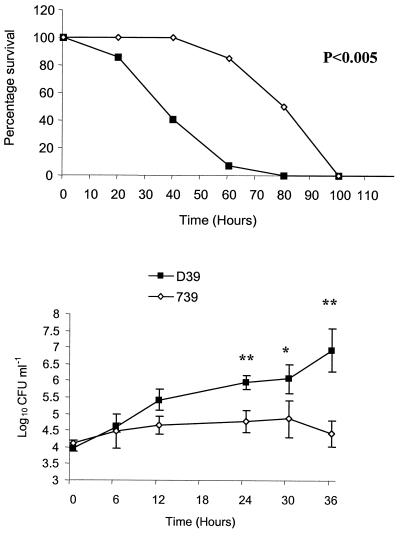

FIG. 3.

Intranasal challenge. Mice were challenged intranasally with 106 CFU of the Δ739 mutant and D39 parental strains. (Top panel) Survival of mice. The difference in the median survival time of mice infected with the Δ739 mutant compared to the D39 parental strain was significant (P < 0.005). (Bottom panel) Bacteremia. Levels of bacteremia for the Δ739 mutant compared to D39 were statistically lower at 24 h (P < 0.005) (**) and 36 h (P < 0.05) (*) postinfection. Counts for wild-type bacteria were not included at 48 h because some of the mice were culled prior to this time point due to severity of infection. The broken line represents the lower limit of detection. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Bacterial counts for both D39 and the Δ739 mutant became detectable in the bloodstream at 12 h postinfection, with the mutant having slightly higher counts than the wild type (not significantly different). However, for all time points studied after 12 h, mice challenged with wild-type bacteria had significantly higher counts in the blood than mice challenged with mutant bacteria (P < 0.005 for 24 h and P < 0.05 for 36 h) (Fig. 3, bottom panel). Indeed, at 24 h postchallenge, the observed mean bacterial count in the blood of mice infected with mutant bacteria was over 1,000-fold less than that seen with wild-type infection. Bacteremia in the blood of mice infected with D39 at 48 h postchallenge was not determined, as over 40% of mice had been culled by this time due to severity of infection. It thus appears that during the early stages of infection the mutant bacteria can gain entry into the bloodstream but that they are then impaired in their ability to grow in the blood, showing no significant increase in numbers between 12 and 24 h. This is in contrast to D39 growth in the blood, which increases from log10 2.9 CFU ml of blood−1 at 12 h to log10 6.3 CFU ml of blood−1 at 24 h postinfection, an increase of over 1,000-fold. Despite the slower growth of the mutant strain in the bloodstream, counts do eventually increase to a level which results in the appearance of severe clinical signs and eventual mortality. Δ739 mutant-infected mice in a moribund state had counts of 107 to 109 CFU ml of blood−1, which is comparable to levels in moribund mice infected with the D39 wild-type strain.

An unusual feature observed following intranasal infection with the Δ739 mutant was the late onset of clinical signs which subsequently appeared to persist in the milder stages for longer periods of time compared to the progression of clinical signs characteristic of wild-type D39 infection (data not shown). Furthermore, mice challenged with mutant bacteria often showed mild to moderate signs of infection for up to 5 days, after which the mice often appeared to recover and to be free of clinical signs. Following this recovery a rapid relapse was frequently observed, where mice showed moderate to severe signs of infection within 6 to 12 h of appearing to be completely healthy. Such mice had to be sacrificed soon after the development of these clinical signs. These observations are unusual for pneumococcal infection of MF1 mice with D39, where, following infection and the onset of mild clinical signs, the mice progress through several stages of infection, displaying moderate (intense piloerection and hunched stance) and then severe (lethargy) clinical signs of disease until they become severely lethargic and eventually moribund. The moribund state is usually reached within 24 to 48 h of the mice showing initial signs of infection, and recovery from even mild clinical signs is a rare occurrence.

(ii) Stability of the Δ739 mutant.

At 36 h postchallenge, counts in the blood of mice were used to determine if the Δ739 mutant retained its spectinomycin selection marker as a measure of the stability of the mariner mutation during in vivo infection. The mutant was found to be stable for up to 36 h in the blood of infected mice (data not shown). PCR was also used to confirm the presence of the mariner cassette in zmpB in a selection of the mutants recovered from in vivo infection (data not shown). This observation is not surprising as, in contrast to insertion-duplication mutations, a mariner insertion is not expected to be unstable.

(iii) Colonization of the airways and lung tissue.

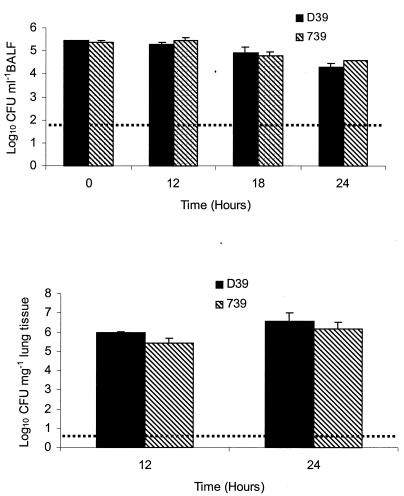

To determine the number of bacteria in the murine airways and lung tissue, mice were challenged intranasally as described above. Lavage fluid and lungs were removed at predetermined time points and used for enumeration of viable cells. No significant difference in colonization of the airways or lung tissue was found between the D39 wild-type strain and the Δ739 mutant for any of the time points examined (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Colonization of airways and lungs. Mice were challenged intranasally with 106 CFU of the Δ739 mutant and D39 parental strains. Bacterial counts within the BALF (top panel) and lung tissue (bottom panel) were determined at predetermined time points postinfection. The broken lines represent the lower limits of detection. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Intravenous challenge.

To bypass the respiratory system, bacterial strains were inoculated directly into the systemic circulation of mice to determine their ability to grow in the blood (Fig. 5). Counts at 0 h confirmed the bacterial dose administered, and subsequent levels of bacteremia were measured at predetermined time intervals. Mice were also monitored for survival. All mice challenged intravenously with D39 and the Δ739 mutant succumbed to infection. As described for the intranasal challenges, mice challenged with the Δ739 mutant survived much longer than those infected with the D39 parental strain (P < 0.05), with median survival times of 97 and 46 h, respectively (Fig. 5, top panel). This is >2-fold greater survival for mice challenged with mutant bacteria. Bacterial counts in the blood of mice challenged with mutant bacteria were significantly lower at 24, 30, and 36 h than counts in mice administered wild-type bacteria (Fig. 5, bottom panel). At 24 h, counts within the blood of mice infected with the mutant were 33-fold less than those in the blood of mice challenged with wild-type D39.

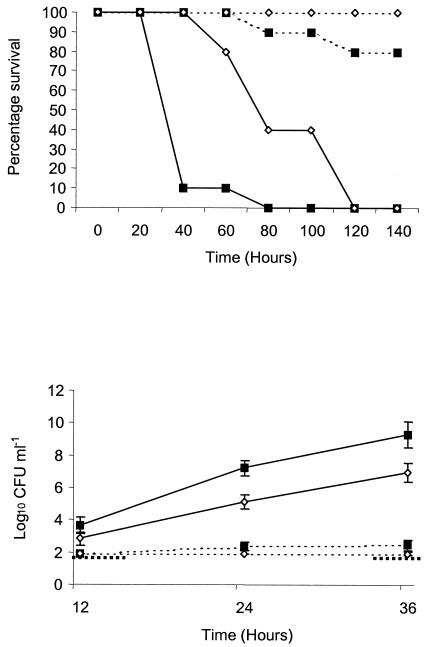

FIG. 5.

Intravenous challenge. Mice were challenged intravenously with 105 CFU of the Δ739 mutant and D39 parental strains. (Top panel) Survival of mice. The difference in the median survival time of mice infected with the Δ739 mutant compared to the D39 parental strain was significant (P < 0.005). (Bottom panel) Bacteremia following challenge. Levels of bacteremia for the Δ739 mutant compared to D39 were statistically significant at 24 h (P < 0.005) (**), 30 h (P < 0.05) (*), and 36 h (P < 0.005) (**) postinfection. The limit of detection (log10 1.92 CFU ml−1) is below the scale used, so is not represented. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Despite showing low counts within the blood at the time points studied, the levels of the Δ739 mutant in the blood appeared to have increased after the 36-h time point, as some of the mice started to show clinical signs between 60 and 80 h postinfection. Furthermore, all mice challenged with the mutant had to be sacrificed by 100 h postchallenge, and when moribund these mice had high counts, comparable to those with wild-type infection, within their blood (107 to 109 CFU ml of blood−1). Again, this suggests that upon entry into the blood the Δ739 mutant is poorly adapted for growth and survival in this environment, although given time it is able to cause lethal infection.

Complement-deficient (C3−/−) mice: survival and bacteremia.

The data presented above indicate that ZmpB has a role in the virulence of D39 in our model of infection. As complement is an important host defense mechanism in pneumococcal infection and a region of ZmpB shows homology with the S. pneumoniae surface protein PspC/complement factor H binding inhibitor, the behavior of the Δ739 mutant in complement deficient C3 knockout mice was characterized. Should interference with host complement activity be a major function of active ZmpB, then the virulence of wild-type and mutant bacterial strains in C3−/− mice would not be expected to differ significantly. C3−/− mice were challenged intranasally with the D39 and Δ739 strains and monitored for survival and bacteremia. Infection of C3−/− mice with the Δ739 mutant resulted in greater murine survival times (P < 0.005) (Fig. 6, top panel) and lower levels of bacteremia at 24 and 36 h postinfection (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6, bottom panel) than infection with wild-type bacteria. The median survival time for C3−/− mice infected with the Δ739 mutant was 73 h. Infection of complement-sufficient, wild-type control mice (C3+/+) and challenge with the Δ739 mutant did not result in detectable bacteremia at any of the time points studied, and all mice survived the challenge.

FIG. 6.

Virulence in complement-deficient mice. Complement-sufficient (C3+/+) (dotted lines) and complement knockout (C3−/−) (solid lines) mice were challenged intranasally with 106 CFU of the D39 (squares) and Δ739 mutant (diamonds) bacterial strains. Mice were monitored for survival (top panel) and bacteremia at predetermined time points (bottom panel). No significant difference was observed between the bacterial strains in the survival or bacterial counts in the blood of C3+/+ mice. In the C3−/− mice, those challenged with mutant bacteria survived significantly longer than those challenged with the D39 parental strain (P < 0.005). Similarly, for bacterial counts in the blood of mice, no difference was seen between bacterial strains in wild-type C3+/+ mice, but in C3−/− mice, lower bacterial counts were observed at all time points examined following challenge with mutant bacteria compared to the D39 parental strain. This difference was statistically significant for 24 and 36 h postinfection (P < 0.05). The boldface broken line represents the lower limit of detection for bacterial counts in the blood and has been interrupted to allow visualization of the low bacterial counts in wild-type C3+/+ mice. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Following challenge with the D39 parental strain, C3−/− mice quickly succumbed to infection, with a median survival time of 36 h and with only 10% surviving the challenge by 40 h postinfection (Fig. 6, top panel). The counts of D39 in the blood increased rapidly, as expected, and reached very high counts of log10 9.54 CFU ml−1 at 36 h postchallenge (Fig. 6. bottom panel). In C3+/+ mice, infection with D39 bacteria resulted in only 20% of the mice succumbing to infection, with counts in the blood barely rising above the limit of detection (Fig. 6, bottom). This illustrates the importance of complement in preventing pneumococcal infection in this murine model of infection.

The data above indicate that the Δ739 mutant is also impaired in virulence in the C3−/− mice compared to the D39 wild-type strain. This suggests that interference with the host's complement system is not a major function of active ZmpB in strain D39 when assessed in C3−/− mice on a C57BL background.

Role of ZmpB in inflammation.

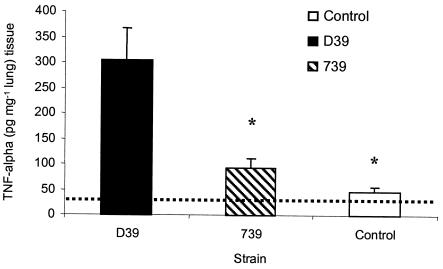

The work with the C3−/− mice presented above indicates that ZmpB does not interfere with complement function. Another host defense mechanism that is both important in clearing pneumococcal infection and implicated in the pathology of infection is the host inflammatory response mediated by inflammatory cytokines. Thus, the inflammatory response within the respiratory system was characterized to determine if ZmpB could act within this environment to promote or inhibit inflammation. The concentration of TNF-α, a proinflammatory cytokine released in the lung tissue following intranasal challenge, was examined (Fig. 7). Controls were set up with lung samples taken from uninfected mice and from mice immediately following challenge with both D39 and the Δ739 mutant. Subsequent analysis showed that there were no significant differences between the TNF-α concentrations in uninfected mice and infected mice immediately following challenge (data not shown), so all subsequent data show the value for uninfected mice as the control value. This control therefore represents both a 0-h time point and uninfected mice.

FIG. 7.

TNF-α in lung tissue. Mice were challenged intranasally with 106 CFU of the Δ739 mutant and D39 parental strain. At predetermined time points, lung tissue was removed and snap frozen. Cytokine analysis was performed on samples by using standard ELISA kits. The TNF-α concentration in the lung at 24 h postinfection is shown. Significantly lower levels of TNF-α were observed in the lung tissue of control mice and mice infected with the Δ739 mutant compared to wild-type-infected mice (P < 0.05). The broken line represents the lower limit of detection. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

An ELISA specific for TNF-α was used to demonstrate a significant increase in the concentration of TNF-α within lung tissue at 24 h postinfection with the D39 wild-type strain compared to the Δ739 mutant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

A zmpB null mutant was created in an encapsulated, virulent, serotype 2 strain of S. pneumoniae by using mariner mutagenesis (1). This mutant, the Δ739 mutant, was used to reevaluate some of the published data with respect to the function and expression of ZmpB in vitro and to show that ZmpB has a role in virulence in a murine model of infection.

The Δ739 mutant was not impaired in growth in vitro, indicating that ZmpB is not essential for growth in BHI (data not shown). However, RT-PCR was used to show that the zmpB gene is expressed by D39 during the mid-exponential phase of growth in BHI (data not shown). This indicates that the gene may be constitutively expressed or switched on prior to the stage of growth tested. Furthermore, we provided evidence that the two-component signal transduction system upstream of zmpB (TCS09) is not required for expression of ZmpB under the conditions used. This does not exclude the possibility that this signal transduction system may regulate the expression of ZmpB in some way, but it indicates that we must exercise caution when using the ZmpS/R nomenclature to refer to this particular two-component system. To avoid confusion with regard to the putative function of this two-component system, we will use the nomenclature TCS09 given in the published study that originally identified all 13 pneumococcal two-component signal transduction systems (27).

The Δ739 mutant exhibited cell morphology identical to that of the wild-type parental strain, indicating the presence of functional LytB, a choline binding protein required for daughter cell separation (10). Upon treatment with DOC, an allosteric activator of the LytA autolytic enzyme, all strains were completely lysed within 15 min of treatment, indicating the presence of functional LytA, which is also a choline binding protein (55). Furthermore, the Δ739 mutant transformed at the same frequency as the wild type. This confirms that the presence of capsule does not result in altered phenotypes of the Δ739 mutant in vitro (1).

ZmpB was shown to contribute significantly to the virulence of S. pneumoniae in models of pneumonia and septicemia, based on increased survival times and decreased bacterial counts in the blood of mice infected with the Δ739 mutant compared to wild-type D39 infection. Based on homology of a region of ZmpB with Hic/PspC, we postulated that ZmpB could have a role in binding factor H and subsequently prevent complement-mediated opsonization of wild-type bacteria. However, our data do not support the hypothesis that ZmpB interacts significantly with complement in C3-deficient mice. These mice are unable to produce complement component C3, a crucial part of both the alternative and classical complement pathways, and are thus unable to mount any C3-associated response to infection. When compared to wild-type bacteria, the Δ739 mutant showed the same attenuated phenotype in C3−/− mice as observed in MF1 mice. This suggests that complement is important in clearing both the D39 wild-type strain and the Δ739 mutant, whereas had the hypothesis been correct, similar levels of virulence for the wild-type and mutant bacteria in C3−/− would have been observed. Although ZmpB was not shown to interact with complement, the work with the C3−/− mice highlights the importance of complement in the response to pneumococcal infection (5, 9, 18; our unpublished data).

Following intranasal challenge, the reduced levels of bacteremia in the blood of mice challenged with the Δ739 mutant compared to the wild type from 24 h postchallenge onward could indicate that wild-type bacteria are better able to survive in the blood. It could also suggest that after 24 h more wild-type bacteria are able to disseminate from the lung tissue into the bloodstream. As the inflammatory response is thought to result in tissue damage (2, 26), it was hypothesized that a more vigorous host response in the lung tissue during wild-type infection could compromise tissue integrity and allow bacteria to gain further entry into the bloodstream. To test this hypothesis, levels of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α within the respiratory tract were determined following challenge with wild-type and mutant bacteria. TNF-α was chosen based on its role as a potent proinflammatory cytokine that has been characterized previously with regard to its role in pneumococcal pneumonia (2, 53, 26). It is also one of the first inflammatory mediators to be produced following pneumococcal infection (38) and is thus important in initiating the inflammatory response. Following intranasal infection, increased levels of TNF-α were found in the lung tissue at 12 and 24 h postchallenge with the wild-type bacteria compared to the Δ739 mutant (only data for 24 h are shown). These data strongly indicate that ZmpB is involved in inflammation by inducing an increased TNF-α concentration in the lungs. This could have important implications during human infection, where high TNF-α has been associated with fatal outcome (58). As the pneumococcal toxin pneumolysin is known to be a potent mediator of inflammation (4, 34, 42), the presence of this toxin in wild-type and mutant bacterial strains was compared to determine if differences in pneumolysin activity between strains could account for the different inflammatory profiles. Western blotting confirmed the presence of pneumolysin in both strains, and a hemolytic assay was used to show that both wild-type and mutant strains possessed similar amounts of active pneumolysin (data not shown). However, these observations were based on in vitro experiments in which cultures were actively lysed by DOC to assess hemolytic activity, and thus they do not provide evidence that the strains produce similar amounts of pneumolysin during in vivo infection. Thus, the mechanism by which ZmpB alters the levels of TNF-α is unknown. The Hic/PspC pneumococcal protein has been shown to induce proinflammatory molecules from human A549 epithelial cells (30, 35). As ZmpB shows some homology to Hic, it may share the ability to cause the release of inflammatory cytokines from lung epithelial cells, and this could influence TNF-α production.

Zinc metalloproteases have previously been shown to have important roles in the virulence of several pathogens (13, 47, 62). A number of pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella pneumophila, produce proteases capable of degrading cytokines (16, 17, 33, 41). In contrast, there are examples of bacterial proteases that are able to activate cytokines via cleavage of the precursor form into its active form (24). Similarly, bacterial proteases that can cleave cytokine receptors have been found (59). Bacterial proteins capable of activating matrix metalloproteases have also been described (39).

Pneumococcal colonization and adhesion to host tissues constitute a crucial step in initiation of the disease process and are thus a potential target of both prophylactic and therapeutic treatment. It has been proposed that inflammatory cytokines induced by bacterial factors may up-regulate expression of host proteins that can subsequently be utilized by the pneumococcus for adhesion (23, 25, 49). It could thus be hypothesized that increased levels of TNF-α induced by wild type D39 may promote adhesion by the up-regulation of host factors used for pneumococcal attachment. Work in this study indicated that the Δ739 mutant was not impaired in its ability to colonize murine airways or lung tissue. This does not support a link between inflammation and increased adhesion, at least in the tissues examined.

Aside from its role in inducing inflammation within the lung tissue, ZmpB appears to have other functions important in virulence, as demonstrated by the observation that the Δ739 mutant shows attenuated growth following direct inoculation into the bloodstream compared to its isogenic parental strain, D39. Whether this attenuation represents more efficient control of the invading bacteria by the host's immune system and/or a reduced ability of the mutants to obtain essential nutrients in this environment has not been determined. These data suggest that the role of ZmpB in virulence is multifactorial and that its function in inducing inflammation combined with its role in systemic infection enhances virulence in wild-type bacteria. Being such a large protein, ZmpB, like pneumolysin, might have separate regions within the protein that contribute differently to virulence. Mice infected with the Δ739 mutant displayed unusual symptoms and often rapidly relapsed after apparent recovery from infection. This relapse correlated with high levels of bacteremia, suggesting that ZmpB may have an important role in the earlier stages of infection. Further experiments to examine the role of ZmpB in pneumococcal infection are required.

This study has provided evidence that ZmpB has a significant role in virulence of a serotype 2 pneumococcus and that its role in virulence is multifactorial. Given the contribution of inflammation to tissue pathology following pneumococcal infection (26, 58) and the observation that a patient may die even when the infecting bacteria have been successfully eliminated (2, 6), the identification and characterization of bacterial components that contribute to inflammation will be of great benefit to the future control of S. pneumoniae infections. The identification of ZmpB as being important in virulence through the use of several genome-wide screens with different pneumococcal strains highlights that ZmpB is important in virulence across various serotypes and strains. Our data have expanded on the importance of ZmpB in virulence in models of pneumonia and septicemia and have identified this protein as a mediator of inflammation in the lung. Further analysis of ZmpB may thus prove useful in the study of the inflammatory response to pneumococcal and other bacterial infections and may demonstrate this protein to be a suitable candidate for future therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MRC. C. Blue is the recipient of an MRC studentship.

We acknowledge Mike Carroll (Harvard University, Boston, Mass.) and James Marsh (Guy's Hospital, London, United Kingdom) for provision of C3−/− mice.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergé, M., P. Garcia, F. Iannelli, M. F. Prere, C. Granadel, A. Polissi, and J.-P. Claverys. 2001. The puzzle of zmpB and extensive chain formation, autolysis defect and non-translocation of choline-binding proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1651-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron, Y., N. Ouellet, A.-M. Deslauriers, M. Simard, M. Olivier, and M. G. Bergeron. 1998. Cytokine kinetics and other host factors in response to pneumococcal pulmonary infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:912-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard, D. K., J. K. Djeu, T. W. Klein, H. Friedman, and W. E. Stewart II. 1988. Protective effects of tumour necrosis factor in experimental Legionella pneumophila infections of mice via activation of PMN function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 43:429-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Blue, C. E., and T. Mitchell. 2003. Contribution of a response regulator to the Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae is strain dependent. Infect. Immun. 71:4405-4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Braun, J. S., R. Novak, G. Gao, P. J. Murray, and J. L. Shenep. 1999. Pneumolysin, a protein toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, induces nitric oxide from macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:3750-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, J. S., T. Hussell, S. M. Gilliland, D. W. Holden, J. C. Paton, M. R. Ehrenstein, M. J. Walport, and M. Botto. 2002. The classical pathway is the dominant complement pathway required for innate immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16969-16974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler, J. C., and M. S. Cetron. 1999. Pneumococcal drug resistance: the new “special enemy of old age.” Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:730-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canvin, J. R., A. P. Marvin, M. Sivakumaran, J. C. Paton, G. J. Boulnois, P. W. Andrew, and T. J. Mitchell, T. J. 1995. The role of pneumolysin and autolysin in the pathology of pneumonia and septicemia in mice infected with a type 2 pneumococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 172:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman, C., N. C. Munro, P. K. Jeffery, T. J. Mitchell, P. W. Andrew, G. J. Boulnois, D. Guerreiro, J. A. L. Rohde, H. C. Todd, P. J. Cole, and R. Wilson. 1991. Pneumolysin induces the salient histologic features of pneumococcal infection in the rat lung in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 5:416-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueroa, J. E., and P. Densen. 1991. Infectious diseases associated with complement deficiencies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:359-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia, P., M. P. Gonzalez, E. Garcia, R. Lopez, and J. L. Garcia. 1999. LytB, a novel pneumococcal murein hydrolase essential for cell separation. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1275-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammerschmidt, S., S. R. Talay, P. Brandtzaeg, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1997. SpsA, a novel pneumococcal surface protein with specific binding to secretory immunoglobulin A and secretory component. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1113-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammerschmidt, S., M. O. Tillig, S. Wolff, J.-P. Vaerman, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2000. Species-specific binding of human secretory component to SpsA protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae via a hexapeptide motif. Mol. Microbiol. 36:726-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hase, C. C., and R. A. Finlekstein. 1993. Bacterial extracellular zinc-containing metalloproteases. Microbiol. Rev. 57:823-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hava, D. L., and A. Camilli. 2002. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1389-1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havarstein, L. S., G. Coomaraswamy, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11140-11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hell, W., A. Essig, S. Bohnet, S. Gatermann, and R. Marre, R. 1993. Cleavage of tumour necrosis factor-alpha by Legionella exoprotease. APMIS 101:120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvat, R. T., and M. J. Parmley. 1988. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease degrades human gamma interferon and inhibits its bioactivity. Infect. Immun. 56:2925-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hostetter, M. K. 2000. Opsonic and nonopsonic interactions of C3 with Streptococcus pneumoniae, p. 309-313. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. Mary Ann Liebert, Larchmont, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Houldsworth, S., P. W. Andrew, and T. J. Mitchell. 1994. Pneumolysin stimulates the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β by human mononuclear phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 62:1501-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannelli, F., M. R. Oggioni, and G. Pozzi. 2002. Allelic variation in the highly polymorphic locus pspC of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene 284:63-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janulczyk, R., F. Iannelli, A. G. Sjoholm, G. Pozzi, and L. Bjorck. 2000. Hic, a novel surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae that interferes with complement function. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37257-37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarva, H., R. Janulczyk, J. Hellwage, P. F. Zipfel, L. Bjorck, and S. Meri. 2002. Streptococcus pneumoniae evades complement attack and opsonophagocytosis by expressing the pspC locus-encoded Hic protein that binds to short consensus repeats 8-11 of factor H. J. Immunol. 168:1886-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadioglu, A., S. Taylor, F. Iannelli, G. Pozzi, T. J. Mitchell, and P. W. Andrew. 2002. Upper and lower respiratory tract infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae is affected by pneumolysin deficiency and differences in capsule type. Infect. Immun. 70:2886-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapur, V., M. W. Majesky, L. L. Li, R. A. Black, and J. M. Musser. 1993. Cleavage of interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) by a conserved extracellular cysteine protease from Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7676-7680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly, T., J. P. Dillard, and J. Yother. 1994. Effect of genetic switching of capsular type on virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 62:1813-1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr, A. R., J. J. Irvine, J. J. Search, N. A. Gingles, A. Kadioglu, P. W. Andrew, W. L. McPheat, C. G. Booth, and T. J. Mitchell. 2002. Role of inflammatory mediators in resistance and susceptibility to pneumococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 70:1547-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange, R., C. Wagner, A. Saizieu, N. Flint, J. Molnos, M. Stieger, P. Caspers, M. Kamber, W. Keck, and K. Amrein. 1999. Domain organization and molecular characterization of 13 two-component systems identified by genome sequencing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene 237:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima, E. C., I. Garcia, M. H. Vicentelli, P. Vassalli, and P. Minoprio. 1997. Evidence for a proteolytic role of tumor necrosis factor in the acute phase of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:457-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macrina, F. L., J. A. Tobian, K. R. Jones, P. Evans, and D. B. Clewell. 1982. A cloning vector able to replicate in Escherichia coli and Streptococcus sanguis. Gene 19:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen, M., Y. Lebenthal, Q. Cheng, B. L. Smith, and M. K. Hostetter. 2000. A pneumococcal protein that elicits interleukin-8 from pulmonary epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1330-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marra, A., J. Asundi, M. Bartilson, S. Lawson, F. Fang, J. Christine, C. Wiesner, D. Brigham, W. P. Schneider, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2002. Differential fluorescence induction analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae identifies genes involved in pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 70:1422-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That., and O. Schneewind. 2001. Sortase-catalysed anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1049-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mintz, C. S., R. D. Miller, N. S. Gutgsell, and T. Malek. 1993. Legionella pneumophila protease inactivates interleukin-2 and cleaved CD4 on human T cells. Infect. Immun. 61:3416-3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell, T. J., and P. W. Andrew. 2000. Biological properties of pneumolysin, p. 279-286. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. Mary Ann Liebert, Larchmont, N.Y.

- 35.Murdoch, C., R. C. Read, Q. Zhang, and A. Finn. 2002. Choline-binding protein A of Streptococcus pneumoniae elicits chemokine production and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD54) by human alveolar epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1253-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neeleman, C., S. P. M. Geelen, P. C. Aerts, M. R. Daha, T. E. Mollnes, J. J. Roord, G. Posthuma, H. van Dijk, and A. Fleer. 1999. Resistance to both complement activation and phagocytosis in type 3 pneumococci is mediated by the binding of complement regulatory protein factor H. Infect. Immun. 67:4517-4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novak, R., E. B. Charpentier, E. Park, S. Murti, E. Tuomanen, and R. Masure. 2000. Extracellular targeting of choline-binding proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae by a zinc metalloprotease. Mol. Microbiol. 36:366-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Brien, D. P., D. E. Briles, A. J. Szalai, A. H. Tu, I. Sanz, and M. H. Nahm. 1999. Tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor I is important for survival from Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. Infect. Immun. 67:595-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamoto, T., T. Akaike, M. Suga, S. Tanase, H. Horie, S. Miyajima, M. Ando, Y. Ichinose, and H. Maeda. 1997. Activation of human matrix metalloproteinases by various bacterial proteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:6059-6066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pallen, M. J., A. C. Lam, M. Antonio, and K. Dunbar. 2001. An embarrassment of sortases—a richness of substrates? Trends Microbiol. 9:97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parmley, M., A. Gale, M. Clabaough, R. Horvat, and W.-W. Zhou. 1990. Proteolytic inactivation of cytokines by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 58:3009-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paton, J. C. 1996. The contribution of pneumolysin to the pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Trends Microbiol. 4:103-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plaut, A. G. 1983. The IgA1 proteases of pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37:603-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polissi, A., A. Pontiggia, G. Feger, M. Altieri, H. Mottl, L. Ferrari, and D. Simon. 1998. Large-scale identification of virulence genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 66:5620-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rawlings, N. D., and A. J. Barrett. 1995. Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases, p. 183-225. In A. J. Barrett (ed.), Proteolytic enzymes: aspartic and metallo peptidases. Academic Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 46.Riesenfeld-Orn, I., S. Wolpe, J. F. Garcia-Bustos, M. K. Hoffmann, and E. Tuomanen. 1989. Production of interleukin-1 but not tumor necrosis factor by human monocytes stimulated with pneumococcal cell surface components. Infect. Immun. 57:1890-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schiavo, G., B. Benfenati, B. Poulain, O. de Rossetto, P. P. Laureto, B. R. DasGupta, and C. Montecucco. 1992. Tetanus and botulinum-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature 359:832-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith, B. L., and M. K. Hostetter. 2000. C3 as a substrate for adhesion of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 182:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sollid, L. M., D. Kvale, P. Brandtzaeg, G. Markussen, and E. Thorsby. 1987. Interferon-gamma enhances expression of secretory component, the epithelial receptor for polymeric immunoglobulins. J. Immunol. 138:4303-4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinshamn, S., M. H. Bemelmans, L. J. van Tits, K. Bergh, W. A. Buurman, and A. Waage. 1996. TNF receptors in murine Candida albicans infection: evidence for an important role of TNF receptor p55 in antifungal defence. J. Immunol. 157:2155-2159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stephenson, K., and J. A. Hoch. 2002. Virulence- and antibiotic resistance-associated two-component signal transduction systems of Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria as targets for antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 93:293-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takashima, K., K. Tateda, T. Matsumoto, Y. Iizawa, M. Nakao, and K. Yamaguchi. 1997. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in pathogenesis of pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:257-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Diodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomasz, A., P. Moreillon, and G. Pozzi. 1988. Insertional inactivation of the major autolysin gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 170:5931-5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuomanen, E., R. Austrian, and H. R. Masure. 1995. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1280-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Der Poll, T., A. Marchant, C. Keogh, M. Goldman, and S. F. Lowry. 1996. Interleukin-10 impairs host defense in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 174:994-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Dissel, J. T., P. Van Langevelde, R. G. J. Westendorp, K. Kwappenberg, and M. Frolich. 1998. Anti-inflammatory cytokine profile and mortality in febrile patients. Lancet 351:950-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vollmer, P., I. Walev, S. Rose-John, and S. Bhakdi. 1996. Novel pathogenic mechanism of microbial metalloproteinases: liberation of membrane-anchored molecules in biologically active form exemplified by studies with the human interleukin-6 receptor. Infect. Immun. 64:3646-3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wessels, M. R., P. Butko, M. Ma, H. B. Warren, A. L. Lage, and M. C. Carroll. 1995. Studies of group B streptococcal infection in mice deficient in complement component C3 or C4 demonstrate an essential role for complement in both innate and acquired immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11490-11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wizemann, T. M., J. H. Heinrichs, J. E. Adamou, A. L. Erwin, G. H. Choi, S. C. Barash, C. A. Rosen, H. R. Masure, E. Tuomanen, A. Gayle, Y. A. Brewah, W. Walsh, P. Barren, R. Lathigra, M. Hanson, S. Langermann, S. Johnson, and S. K. Koenig. 2001. Use of a whole-genome approach to identify vaccine molecules affording protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 69:1593-1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wretlind, B., and O. R. Pavlovskis. 1983. Pseudomonas elastase and its role in Pseudomonas infections. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5(Suppl.):998-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]