Abstract

CBA/J mice immunized with pneumococcal 23F-CRM197 vaccine produce significantly lower titers of 23F-specific antibodies and fewer 23F-specific antibody-secreting cells (ASC) than did BALB/c or (CBA/J × BALB/c)F1 (CCBAF1) mice. The reduced 23F-specific titers of CBA/J versus BALB/c or CCBAF1 mice are presumably related to lower frequencies of 23F-specific ASC influenced by genetic variation.

The multivalent pneumococcal (Pn) polysaccharide (PS)-protein conjugate vaccine includes seven different Pn serotypes separately conjugated to the identical carrier protein CRM197 (cross-reactive material, a nontoxic diphtheria toxin mutant). In contrast to the unconjugated PnPS vaccines, this vaccine protects infants against infection with vaccine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae (6, 7). Despite the covalent coupling of each PnPS component of the multivalent conjugate vaccine to the same carrier protein, some serotypes elicit relatively low titers of PS-specific antibodies (2, 3, 6). Evidence obtained with mice and humans demonstrates that responsiveness to PnPS in general may be genetically controlled (1, 4, 5).

We previously described low 23F-specific antibody titers after immunization with the 23F-CRM197 vaccine in CBA/J mice, despite high CRM197-specific antibody titers and the presence of CRM197-reactive T cells (3). Immunization of CBA/J mice with 6B-CRM197 or 19F-CRM197 conjugate vaccines resulted in high levels of both PS- and CRM197-specific antibodies. Although immunization with 23F-CRM197 yielded responses to different sets of CRM197-derived peptides than did immunization with the 6B-CRM197 and 19F-CRM197 conjugates, the overall levels of T-cell proliferation in response to any of the different conjugates were comparable. Thus, we concluded that the apparent qualitative alterations in the T-cell response to 23F-CRM197 in CBA/J mice were unlikely to be responsible for the poor immunogenicity of serotype 23F PS (3).

In the present study, we asked if the weak PS-specific antibody responses of CBA/J mice following immunization with 23F-CRM197 is influenced by genetic differences between distinct inbred strains of mice. Therefore, we compared responses to 23F-CRM197 conjugate vaccine among CBA/J, BALB/c, and (CBA/J × BALB/c)F1 (CCBAF1) mice. Both serum titers of 23F-specific antibody and numbers of 23F-specific antibody-secreting cells (ASC) after immunization were assessed.

Mice of the three genetic backgrounds (CBA/J, BALB/c, and CCBAF1) were immunized intraperitoneally with either 19F-CRM197 or 23F-CRM197 and boosted 2 weeks later. Eight-week-old pathogen-free female mice were immunized with 10 μg (PS content) of 19F-CRM197 or 23F-CRM197 (kindly supplied by Ron Eby, Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines, West Henrietta, N.Y.). The PS/protein mass ratios of the vaccines were as follows: 19F-CRM197, 0.66; 23F-CRM197, 0.52 (R. Eby, personal communication). CBA/J and BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). CCBAF1 mice were obtained by in-house breeding. Ten micrograms of PnPS was chosen as the immunizing dose because previous experiments had demonstrated that this is the minimal amount of antigen that is able to yield maximal or near-maximal antibody titers in CBA/J mice (3). Mice immunized with sterile phosphate-buffered saline served as negative controls. Sera were screened for anti-PnPS and anti-CRM197 antibodies via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in which 96-well plates were coated with PnPS or CRM197 as previously described (3). Quantitation of antigen-specific antibody levels was based on standard curves generated with distinct murine monoclonal antibodies specific for, respectively, 19F PS (59-1; immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]), 23F PS (53-2; IgG1), or CRM197 (E7-10; IgG1). The monoclonal antibodies were all generously provided by Phil Fernsten, Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines.

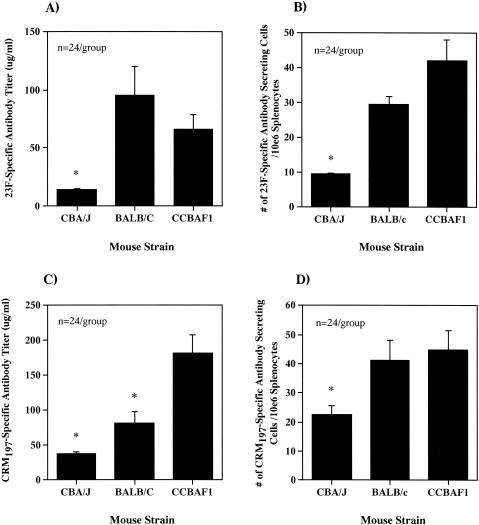

Immunization of CBA/J mice with 23F-CRM197 resulted in low-level anti-23F antibody titers. In contrast, immunization of BALB/c and CCBAF1 mice with 23F-CRM197 resulted in 23F-specific antibody titers significantly greater than those of CBA/J mice (P < 0.004) (Fig. 1A). CBA/J and BALB/c mice also produced significantly lower titers of CRM197-specific antibodies (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

23F- and CRM197-specific responses of BALB/c, CBA/J, and CCBAF1 mice after two immunizations with 23F-CRM197. (A) Total 23F-specific serum immunoglobulin κ chain titers (micrograms per milliliter) detected by PnPS solid-phase ELISA. (B) Frequency of 23F-specific κ ASC determined by PnPS solid-phase ELISpot assay. The data shown are a compilation of two experiments with the mean ± the standard error of the mean of a total of 24 mice per group. *, P < 0.004. (C)Total CRM197-specific serum immunoglobulin κ chain titers (micrograms per milliliter) detected by CRM197 solid-phase ELISA. (D) Frequency of CRM197-specific κ ASC determined by PnPS solid-phase ELISpot assay. The data shown are a compilation of two experiments with the mean ± the standard error of the mean of a total of 24 mice per group. *, P < 0.003 for comparisons of selected groups with CCBAF1.

We also determined the frequencies of PS- and CRM197-specific ASC by ELISpot assay after immunization with 23F-CRM197 as previously described (2, 8). Multiscreen plates (Millipore) were coated with 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 10 μg of 19F or 23F PS per ml or 1 μg of CRM197 per ml. Spleens were harvested 6 days after a secondary immunization, a single-cell suspension was prepared, and 106 cells were added to each well after washing. ASC were detected with goat anti-mouse κ-alkaline phosphatase and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP)-nitroblue tetrazolium in nitroblue tetrazolium buffer (Sigma). The spots were enumerated with an ImmunoSpot series 1.0 analyzer (Optimas, Bothell, Wash.). Spots could not be detected in unimmunized mice or in mice immunized once in our assay system (data not shown).

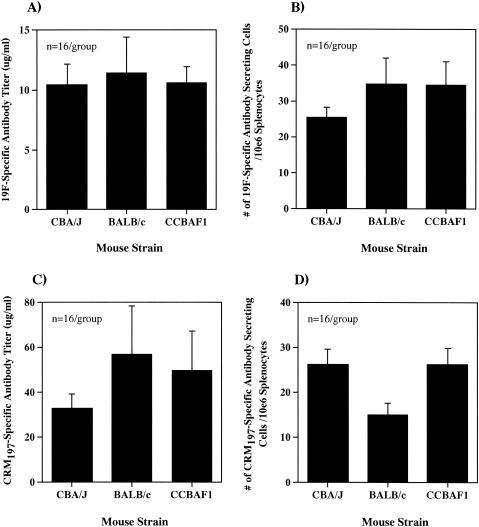

The frequencies of both 23F- and CRM197-specific ASC were substantially decreased (P < 0.004 and P < 0.03, respectively) in CBA/J mice in comparison to the 23F- and CRM197-specific ASC frequencies of BALB/c and CCBAF1 mice (Fig. 1B and D), consistent with the serum antibody measurements. In contrast to these results, immunization of CBA/J, BALB/c, and CCBAF1 mice with 19F-CRM197 yielded roughly comparable serum antibody titers and ASC with specificities for both 19F PS and CRM197 (Fig. 2A to D). Thus, CBA/J mice have the ability to respond, similarly to BALB/c mice, following immunization with CRM197. The low numbers of 23F-specific ASC in CBA/J mice and the presence of significantly higher numbers in BALB/c and CCBAF1 mice suggest a genetic influence over the antibody response to 23F, such that a stronger response is expressed in a dominant fashion.

FIG. 2.

19F- and CRM197-specific responses of BALB/c, CBA/J, and CCBAF1 mice after two immunizations with 19F-CRM197. (A) Total 19F-specific serum immunoglobulin κ chain titers (micrograms per milliliter) detected by PnPS solid-phase ELISA. (B) Frequency of 19F-specific κ ASC determined by PnPS solid-phase ELISpot assay. The data shown are a compilation of two experiments with the mean ± the standard error of the mean of a total of 16 mice per group. (C) Total CRM197-specific serum immunoglobulin κ chain titers (micrograms per milliliter) detected by CRM197 solid-phase ELISA. (D) Frequency of CRM197-specific κ ASC determined by CRM197 solid-phase ELISpot assay. The data shown are a compilation of two experiments with the mean ± the standard error of the mean of a total of 16 mice per group.

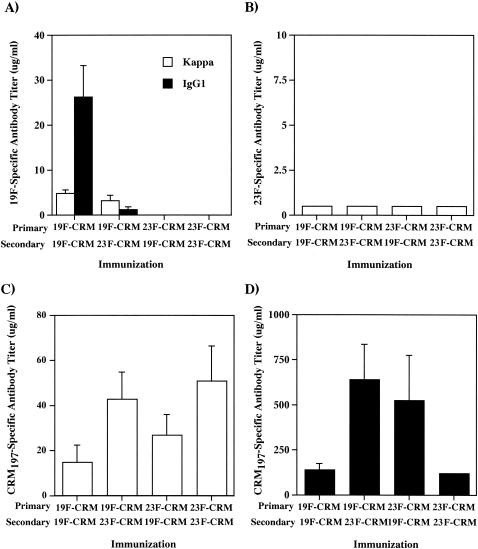

We next sought to determine the ability of CBA/J mice to produce anti-23F antibodies after priming with the immunogenic conjugate 19F-CRM197, thereby potentially eliciting carrier-specific memory T cells in the absence of 23F-specific memory B cells. Mice were immunized with 19F-CRM197 and then immunized 2 weeks later with either 23F-CRM197 or 19F-CRM197. Additional mice were primed with 23F-CRM197 and then immunized with 19F-CRM197 or 23F-CRM197. As expected, mice primed with 19F-CRM197 and boosted with 19F-CRM197 produced anti-19F antibodies primarily of the IgG1 isotype and at titers (Fig. 3A) similar to those produced by BALB/c and CCBAF1 mice (Fig. 2A). Mice primed with 23F-CRM197 and boosted with 23F-CRM197 produced minimal to undetectable levels of 23F-specific antibodies (Fig. 3B). Mice primed with 19F-CRM197, followed by 23F-CRM197, produced levels of 19F-specific antibodies consistent with a single immunization (Fig. 3A), but the level of 23F-specific antibodies remained undetectable. Priming with 23F-CRM197, followed by immunization with 19F-CRM197, also did not yield detectable levels of 23F-specific antibodies (Fig. 3B). These data suggested that lack of CRM197-specific T-cell help due to alterations from the conjugation to the 23F PS was not the cause of the poor 23F-specific antibody response since priming with an immunogenic CRM197 conjugate did not improve the 23F-specific antibody response.

FIG. 3.

PS- and CRM197- specific antibody titers (micrograms per milliliter) of CBA/J mice primed with either 19F-CRM197 or 23F-CRM197 and boosted with either conjugate. Total serum immunoglobulin κ chain titers (micrograms per milliliter) of 19F-specific (A), 23F-specific (B), and CRM197-specific (C) antibodies in CBA/J mice detected by PnPS (A and B) and CRM197 (C and D) solid-phase ELISAs. 19F-specific (A) and CRM197-specific (D) IgG1 levels detected in the same sera are also shown. The mean titers (micrograms per milliliter) ± the standard error of the mean of groups of five mice are shown.

Despite the poor 23F-specific immunogenicity of the 23F-CRM197 conjugate vaccine, CRM197-specific IgG1 antibodies were produced in CBA/J mice after immunization (Fig. 3D). In addition, mice primed with 19F-CRM197 and boosted with 23F-CRM197 and vice versa produced equivalent amounts of CRM197-specific antibodies (Fig. 3C). The CRM197-specific antibody response after the second immunization increased in magnitude and consisted primarily of CRM197-specific IgG1 (Fig. 3D), typical of a T cell-dependent response. These data also suggest that both 19F-CRM197 and 23F-CRM197 are capable of eliciting T-cell help for CRM197-specific B cells, since T-cell help is required for class switching to IgG1 and increased antibody production after reimmunization. However, the presence of this CRM197-specific T-cell help did not result in 23F-specific antibody production. Thus, it is likely that even with the availability of CRM197-derived T-cell help, CBA/J mice are unable to produce a substantial 23F-specific antibody response (3).

In order to determine if the differences in 23F PS- or CRM197-specific immunogenicity between mouse strains after immunization with 23F-CRM197 might involve differences in T-cell responsiveness, we compared both proliferative responses of lymph node cells to whole CRM197 and the specificities of T-cell proliferative responses for CRM197-derived peptides. While the sets of peptides for the CBA/J and BALB/c cells were not identical (although overlapping), the overall proliferative responses to whole CRM197 were comparable (data not shown). These results, in conjunction with the results from sequential immunization with 23F-CRM197 and 19F-CRM197, suggest that the lack of response to 23F PS (and CRM197) by CBA/J mice is not primarily attributable to the T-cell compartment.

The most likely explanation for these findings is a genetically influenced paucity of 23F-specific B-lymphocyte precursors. If in mice, as Zhou et al. (9) found in humans, antibody responses to 23F PS involve a restricted number of light- or heavy-chain variable-region genes, polymorphisms in the relevant variable-region genes might influence the production of 23F-specific precursors. How a relative deficiency of 23F PS-specific precursors in CBA/J mice would account for the relatively poor CRM197-specific antibody responses following immunization of these mice with 23F-CRM197 remains unclear. Perhaps PS-specific B cells represent a significant proportion of the antigen-presenting cell pool for carrier-specific T cells. Although we cannot absolutely rule out the possibility that conjugation of 23F PS to CRM197 generates a uniquely nonstimulatory or inhibitory epitope(s), the ability of 23F-CRM197 to prime effectively for an antibody response to CRM197 upon a challenge with 19F-CRM197 (Fig. 3C and D) argues against these possibilities. Furthermore, we have previously shown that simultaneous immunization with both 23F- and 19F-CRM197 conjugates does not preclude a strong response to 19F PS, suggesting that CRM197-specific T-cell responses were not inhibited by the 23F-CRM197 conjugate (3).

In conclusion, CBA/J mice were poorly responsive after immunization with Pn serotype 23F-CRM197, with antibody titers and 23F-specific ASC frequencies markedly lower than those of BALB/c mice. These results suggest that genetic differences between CBA/J and BALB/c mice contribute to the quantitative differences in the 23F PS-specific antibody responses elicited by 23F-CRM197. Further experiments are necessary to identify murine loci at which allelic variation influences the magnitude of the antibody response to protein-conjugated Pn capsular PS.

Acknowledgments

J.R.S. and N.S.G. share senior authorship.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI41657 (N.S.G.), AI27862 (J.R.S.), and AI32596 (J.R.S.) and a grant from Wyeth Lederle Vaccines.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, P. J., D. W. Bailey, M. B. Fauntleroy, P. W. Stashak, G. Caldes, and B. Prescott. 1985. Genes on different chromosomes influence the antibody response to bacterial antigens. Immunogenetics 22:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamboj, K. K., H. L. Kirchner, R. Kimmel, N. S. Greenspan, and J. R. Schreiber. 2003. Significant variation in serotype-specific immunogenicity of the seven valent Streptococcus pneumoniae-CRM197 conjugate vaccine occurs despite vigorous T cell help induced by the carrier protein. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1629-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCool, T. L., C. V. Harding, N. S. Greenspan, and J. R. Schreiber. 1999. B- and T-cell immune responses to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: divergence between carrier- and polysaccharide-specific immunogenicity. Infect. Immun. 67:4862-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musher, D. M., J. E. Groover, D. A. Watson, J. P. Pandey, M. C. Rodriguez-Barradas, R. E. Baughn, M. S. Pollack, E. A. Graviss, M. de Andrade, and C. I. Amos. 1997. Genetic regulation of the capacity to make immunoglobulin G to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. J. Investig. Med. 45:57-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musher, D. M., D. A. Watson, and R. E. Baughn. 2000. Genetic control of the immunologic response to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Vaccine 19:623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rennels, M. B., K. M. Edwards, H. L. Keyserling, K. S. Reisinger, D. A. Hogerman, D. V. Madore, I. Chang, P. R. Paradiso, F. J. Malinoski, and A. Kimura. 1998. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine conjugated to CRM197 in United States infants. Pediatrics 101:604-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinefield, H. R., S. Black, P. Ray, I. Chang, N. Lewis, B. Fireman, J. Hackell, P. R. Paradiso, G. Siber, R. Kohberger, D. V. Madore, F. J. Malinowski, A. Kimura, C. Le, I. Landaw, J. Aguilar, and J. Hansen. 1999. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal CRM197 conjugate vaccine in infants and toddlers. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:757-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Den Dobbelsteen, G. P., H. Kroes, and E. P. van Rees. 1995. Characteristics of immune responses to native and protein conjugated pneumococcal polysaccharide type 14. Scand. J. Immunol. 41:273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou, J., K. R. Lottenbach, S. J Barenkamp, A. H. Lucas, and D. C. Reason. 2002. Recurrent variable region gene usage and somatic mutation in the human antibody response to the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 23F. Infect. Immun. 70:4083-4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]