Abstract

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled monoclonal antibodies specific for fungal melanin were used in this study to visualize melanin-like components of the Pneumocystis carinii cell wall. A colorimetric enzyme assay confirmed these findings. This is the first report of melanin-like pigments in Pneumocystis.

Members of the genus Pneumocystis are opportunistic pathogens that can cause life-threatening pneumonia in immunocompromised mammalian hosts, including humans. These fungi are host species specific and are ubiquitous in their geographic distribution. Although Pneumocystis species have been studied for about a century, much about these pathogenic fungi remains unknown. This is primarily due to the lack of a reliable, long-term in vitro cultivation system.

The inability to culture Pneumocystis has caused difficulties in studying the most basic biological properties of this fungus. Investigators have searched for evidence of virulence factors of Pneumocystis; however, relatively little has been learned. Because melanin is thought to play a role in the virulence of several fungal pathogens and because of the availability of a monoclonal antibody (MAb) to visualize melanin in Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, and Paracoccidioides (3, 6, 9, 10), we chose to determine whether melanin components were also present in the cell wall of Pneumocystis.

The term “melanin” refers to a member of a group of negatively charged, pigmented, hydrophobic biopolymers with high molecular weights (2). Melanins are typically brown or black, and they exist in all of the animal kingdoms. Many fungal pathogens contain melanin within their cell wall structures, including Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus niger, Alternaria alternata, Cladosporium carionii, Cryptococcus neoformans, Exophiala jeanselmei, Fonsecaea compacta, Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Hendersonula toruloidii, Histoplasma capsulatum, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Penicillium marneffei, Phaeoannellomyces wernickii, Phialophora richardsiae, Phialophora verrucosu, Sporothrix schenckii, Wangiella dermatitidis, and Xylohypha bantiana (1, 3-5, 7, 8). Melanin has been described as a virulence factor for several of these fungi (reviewed in reference 5).

The presence of melanin and the association of melanin with virulence in some fungal pathogens prompted us to determine if the Pneumocystis carinii cell wall contains melanin. By using a MAb specific for fungal melanins (10), we were able to visualize a melanin and/or melanin-like component associated with the cell wall of P. carinii organisms.

Isolation of Pneumocystis organisms and melanin ghosts.

P. carinii was harvested from the lungs of Long Evans rats that were immunosuppressed for ∼10 weeks via 4 mg of dexamethasone per ml (American Reagent, Shirley, N.Y.) in drinking water. The minced rat lungs were homogenized in 10 ml of RPMI 1640 (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) plus 1% glutathione (Sigma, St. Lois, Mo.) for 10 min with a Stomacher Lab Blender 80 (Tekmar, Cincinnati, Ohio). The homogenate was filtered through sterile gauze and then through a 10-μm-pore-diameter TCTP Isopore membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). Aliquots of the purified P. carinii were used for isolation of melanin ghosts, in an immunofluorescence assay, or in an enzyme activity assay.

Melanin ghosts, for use as controls in the immunofluorescence assay, were isolated according to previously described procedures from approximately 1012 Pneumocystis nuclei and A. niger spores (12). Each fungus was incubated in 10 mg of Trichoderma sp. cell wall lysing enzymes per ml (Sigma) and dissolved in 1 M sorbitol-0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5) overnight with rocking at 30°C. The fungi were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then incubated in 4 M guanidine thiocyanate (Sigma) overnight with rocking at room temperature. The cell debris was centrifuged and washed as described above and then incubated in 1 mg of proteinase K per ml (Invitrogen) overnight at 37°C. The cell debris was centrifuged and washed, boiled in 6 M HCl for 1 h, washed in PBS, and then dialyzed against distilled water for 10 days. The end product after this isolation procedure was a brown substance isolated from Pneumocystis and a black substance isolated from A. niger (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Melanin ghost isolates from P. carinii and A. niger. P. carinii melanin ghosts are shown on the left, and A. niger melanin ghosts are shown on the right.

Immunofluorescence detection of fungal melanins.

An immunofluorescence assay was used to visualize melanin in Pneumocystis, Pneumocystis melanin ghosts, Aspergillus melanin ghosts, and P. carinii-infected rat lung tissue. Ten-microliter aliquots of P. carinii, P. carinii melanin ghosts, and A. niger melanin ghosts were air dried and heat fixed onto glass microscope slides. P. carinii-infected rat lung tissue was inflated and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), embedded in paraffin, cut into 10-μm-thick sections, and then adhered to glass microscope slides. The paraffin was removed from the tissue section by soaking in xylene (Fisher) twice for 10 min. The tissue was than rehydrated in a range of 100 to 50% ethanol. All slides were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 2 h, washed, and then digested in 0.1 mg of proteinase K per ml (Invitrogen) at 37°C over 1 h. Slides were then submersed in 10 mM citric acid and heated on a high setting in a microwave for 5 min. The samples were blocked in SuperBlock (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) overnight with rocking at room temperature. The slides were subsequently incubated with a 50-μg/ml concentration of primary antibody (6D2, an anti-melanin mouse immunoglobulin M [IgM] MAb obtained from Josh Nosanchuk, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y.) or mouse IgM isotype control (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. The slides were then washed twice in 0.1% Tween for 5 min and twice in PBS for 5 min. An FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody (1:250 dilution; Sigma) was added to the samples, and this mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C and then washed as described above. The rat lung tissue sections were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) to stain cell nuclei, allowing visualization of lung architecture under fluorescence. The slides were mounted with SlowFade Antifade (Molecular Probes), and the coverslips were sealed with clear nail polish. Samples were visualized under oil immersion with an Axioplan KS400 fluorescent microscope using FITC filters. The lung tissue sections were visualized with an FITC-Texas red-DAPI filter.

P. carinii cell walls contain melanins.

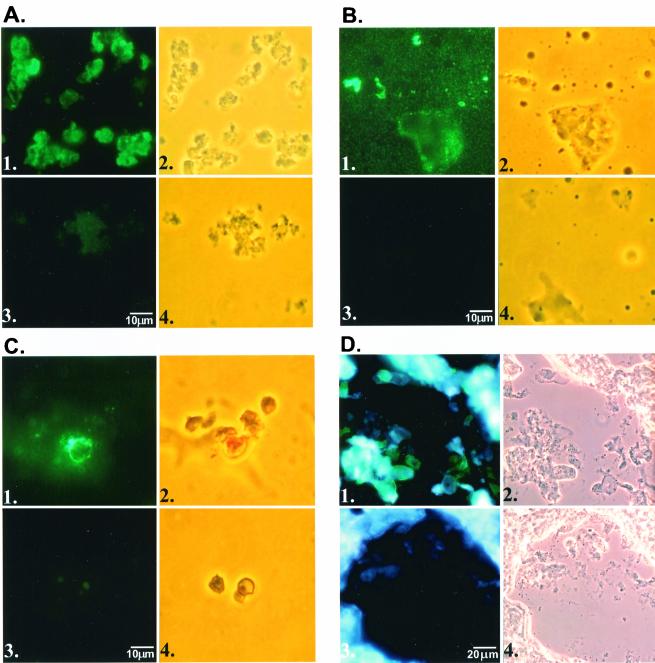

The results from the immunofluorescence assays are shown in Fig. 2. The two upper panels for each sample were incubated with MAb 6D2 recognizing fungal melanins, and the lower panels were incubated with mouse IgM isotype control antibody. These data demonstrate that P. carinii (both cysts and trophozoites), P. carinii melanin ghosts, and A. niger melanin ghosts all bind the MAb 6D2 antibody. In addition, MAb 6D2 bound to P. carinii cysts and trophozoites within infected rat lung tissue (Fig. 2D). Thus, in a fashion parallel to A. niger, the P. carinii cell wall contains melanin or melanin-like components.

FIG. 2.

Evidence for melanins or melanin-like pigments in P. carinii. (A) P. carinii organisms. (B) P. carinii melanin ghosts. (C) A. niger melanin ghosts. (D) P. carinii-infected rat lung tissue section. For each fungal preparation, panel 1 represents staining with the primary antibody, MAb 6D2, viewed under fluorescence microscopy, panel 2 demonstrates phase-contrast microscopy of the identical field shown in panel 1, panel 3 is fluorescence staining performed with isotype control antibody, and panel 4 contains the phase-contrast image of panel 3. Panel D was counterstained with DAPI for visualization of the rat lung tissue under fluorescence.

To confirm the results from the immunofluorescence studies, a colorimetric assay was undertaken to measure phenoloxidase activity in P. carinii. Phenoloxidase is an enzyme required for the polymerization of melanins in several other fungi, including C. neoformans (11). Aliquots of 106 P. carinii organisms were incubated with 10 mM l-epinephrine, a melanin precursor, in the presence of 0 to 5,000 μg of glyphosate (an agent that potently inhibits phenoloxidase activity) per ml (Sigma) for 2 h at 30°C. The reaction was terminated with 10 μl of 1 M KCN (Sigma). The samples were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min, and the A480 of the supernatant was read with a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrophotometer (Columbia, Md.). The results of this assay are shown in Fig. 3. P. carinii was capable of catalyzing the conversion of l-epinephrine into a chromogenic pigment. Furthermore, in a dose-dependent fashion, glyphosate inhibited this reaction. These data suggest that P. carinii has phenoloxidase and further support the contention that P. carinii has the ability to polymerize aromatic precursors into melanin and/or melanin-like pigments.

FIG. 3.

Glyphosate inhibition of putative Pneumocystis phenoloxidase activity. Bar 1 represents P. carinii (Pc) alone, bar 2 is l-epinephrine (Epi) alone, and bars 3 through 10 are derived from P. carinii incubated with l-epinephrine in the presence of the phenoloxidase inhibitor glyphosate at the indicated concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Concluding remarks.

These results demonstrate for the first time that P. carinii has melanin or melanin-like components associated with its cell wall. This study further indicates that P. carinii possesses phenoloxidase enzyme activity and thus possesses the ability to synthesize melanin. Evidence of melanin in P. carinii is of great interest due to the role melanin plays in the virulence of other pathogenic fungi and thus the potential role melanin may play in the pathogenesis of Pneumocystis. Studies to understand the role of melanin in P. carinii pathogenesis and defense from environmental stresses, as well as the biochemical pathway P. carinii uses to synthesize melanin, are currently under way.

Acknowledgments

We thank Josh Nosanchuck, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y. for the generous gift of MAb 6D2. We also thank Joseph Standing for technical support in the generation of Pneumocystis organisms.

This work was funded by NIH grants R01-HL55934 and R01-HL62150 and funds from the Mayo Foundation to A.H.L. C.R.I. was funded by NIH T32 HL-007897-05.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard, M., and J. P. Latge. 2001. Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall: composition and biosynthesis. Med. Mycol. 39:9-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick, T. B. 1965. Mammalian melanin biosynthesis. Trans. St. Johns Hosp. Dermatol. Soc. 51:1-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez, B. L., J. D. Nosanchuk, S. Diez, S. Youngchim, P. Aisen, L. E. Cano, A. Restrepo, A. Casadevall, and A. J. Hamilton. 2001. Detection of melanin-like pigments in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in vitro and during infection. Infect. Immun. 69:5760-5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton, A. J., and B. L. Gomez. 2002. Melanins in fungal pathogens. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:189-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson, E. S. 2000. Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:708-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosanchuk, J. D., B. L. Gomez, S. Youngchim, S. Diez, P. Aisen, R. M. Zancopé-Oliveira, A. Restrepo, A. Casadevall, and A. J. Hamilton. 2002. Histoplasma capsulatum synthesizes melanin-like pigments in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 70:5124-5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polacheck, I., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1988. Melanogenesis in Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:1037-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero-Martinez, R., M. Wheeler, A. Guerrero-Plata, G. Rico, and H. Torres-Guerrero. 2000. Biosynthesis and functions of melanin in Sporothrix schenckii. Infect. Immun. 68:3696-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosas, A. L., J. D. Nosanchuk, M. Feldmesser, G. M. Cox, H. C. McDade, and A. Casadevall. 2000. Synthesis of polymerized melanin by Cryptococcus neoformans in infected rodents. Infect. Immun. 68:2845-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosas, A. L., J. D. Nosanchuck, B. L. Gomez, W. A. Edens, J. H. Henson, and A. Casadevall. 2000. Isolation and serological analyses of fungal melanins. J. Immunol. Methods 244:69-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, Y., P. Aisen, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Cryptococcus neoformans melanin and virulence: mechanism of action. Infect. Immun. 63:3131-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, Y., P. Aisen, and A. Casadevall. 1996. Melanin, melanin “ghosts,” and melanin composition in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 64:2420-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]