Abstract

Aims

Impaired function of the vascular endothelium has been well documented in hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. However, the ‘gold standard’ method for assessing endothelial function, using intra-arterial drug infusion, is invasive and has only been applied in the forearm and coronary circulations in vivo. The aim of the present study was to establish the non-invasive technique of transdermal drug iontophoresis to assess endothelial function in human dermal vessels in vivo.

Methods

In healthy male volunteers, we delivered acetylcholine (ACh) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) to dermal vessels of the forearm using iontophoresis, and measured vasodilatation using laser Doppler fluximetry. Drugs were diluted in a methylcellulose gel vehicle which did not induce vasodilatation. To assess the contribution of nitric oxide and vasoactive prostanoids to cholinergic dilatation, the procedure was repeated during brachial artery infusion of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, l-NG-monomethyl-arginine (l-NMMA) and after intravenous administration of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor, aspirin. As a control for the vasoconstrictor effect of l-NMMA, which was measured by venous occlusion plethysmography, iontophoresis was repeated during brachial artery infusion of noradrenaline.

Results

Flux increased in response to iontophoresis of ACh (from 45±9 to 499±80 units; P < 0.0001) and SNP (from 32±11 to 607±82 units; P < 0.0001). Brachial artery infusions of l-NMMA or noradrenaline caused reductions in forearm blood flow (by 43±2% and 44±2%, respectively) but did not inhibit vasodilatation in response to iontophoresis of ACh or SNP. In contrast, aspirin inhibited the response to iontophoresis of ACh (from 473±81 to 222±43 units; P < 0.0001) but did not affect the response to SNP (from 348±59 to 355±58).

Conclusions

We conclude that in healthy subjects, in contrast to the forearm circulation, dermal vasodilatation in response to iontophoresis of ACh is mediated predominately by a dilator prostanoid rather than by nitric oxide generation. Furthermore, the non-invasive technique of iontophoresis could complement existing invasive tests of endothelial function in future clinical studies.

Keywords: iontophoresis, acetylcholine, prostacyclin, aspirin, l-NG-monomethyl-arginine, endothelium

Introduction

Cholinergic vasodilatation is dependent on a functioning vascular endothelium [1] and may be mediated by generation of nitric oxide [2], prostacyclin [3], or endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor [4]. However, the relative contribution of mediators of endothelium dependent vasodilatation varies between tissues. In renal arteries, prostacyclin is the principal mediator, accounting for the constrictor effect of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in this vascular bed [5, 6]. In the forearm vascular resistance bed, cholinergic vasodilatation is mediated principally by nitric oxide since it can be inhibited by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-NMMA [7], but not by the cyclooxygenase inhibitor aspirin [8].

Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation has been studied in vivo in humans by intra-arterial infusion of acetylcholine (ACh). The forearm [8, 9] and coronary [10] vessels of subjects with hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia demonstrate reduced cholinergic dilatation but normal responsiveness to donors of nitric oxide such as sodium nitroprusside (SNP). It has been proposed that this ‘endothelial dysfunction’ contributes to both vasospasm and platelet aggregation and is therefore causally related to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, it is not clear which endothelium-dependent vasodilator pathways are defective. For example, hypertensive subjects exhibit impaired basal [11, 12] and stimulated [8, 9] nitric oxide generation, as judged by the effects of l-NMMA [11, 12], but indomethacin also normalises their impaired cholinergic dilatation [13]. In addition, it is not established in vivo whether endothelial dysfunction is confined to skeletal muscle resistance vessels and coronary vessels, or, as seems likely, is a generalised phenomenon. Finally, some studies suggest that endothelial dysfunction affects only some patients with hypertension [14]. The invasive methodology of forearm perfusion studies has not allowed sufficient numbers of patients to be examined to establish the epidemiology of endothelial dysfunction.

Against this background, we have investigated the technique of transdermal iontophoresis combined with laser Doppler fluximetry as a non-invasive tool to assess cholinergic dilatation in large numbers of subjects. This report describes the validation of the technique and investigation of the mediators of cholinergic vasodilatation in dermal vessels.

Methods

Subjects

We studied healthy male volunteers aged 23–36 years. Subjects with blood pressure >140/90 mmHg or random serum cholesterol >6 mmol l−1 were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained and studies were approved by the Lothian Ethics of Medical Research Committee. All subjects abstained from vasoactive medication for at least 1 week, and from food, caffeine-containing drinks, alcohol and smoking for at least 4 h, before each study.

Methodology

(i) Iontophoresis

The principle of drug iontophoresis is that an electrical potential difference will actively cause ions in solution to migrate according to their electrical charge (Figure 1). Therefore, the magnitude of an electrical charge (Q) is dependent on the length of time (t) a current (I) is passed (Q = It). In previous studies using iontophoresis [15–17], dermal vasodilatation has occurred following iontophoresis of the vehicle in which drugs are diluted. Before iontophoresing drugs, we sought an inert vehicle in which they could be diluted. Saline (0.9%) and tap water produced iontophoretic responses without addition of drug. Distilled, de-ionised, h.p.l.c.-grade water (Rathburn Chemicals Ltd, Walkerburn, Scotland, UK) produced much smaller responses which were eradicated when iontophoresed in 2% methylcellulose gel (Sigma Chemicals Ltd, Poole, Dorset, UK) (Figure 2). Using this vehicle, we then performed experiments with varying concentrations of ACh and SNP, and varying durations and levels of current (data not shown), and developed the following protocol.

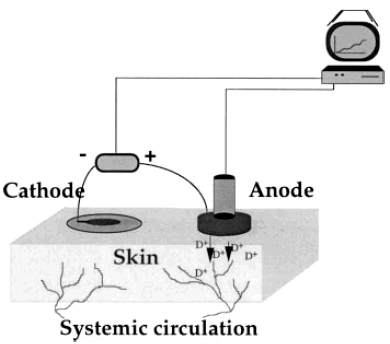

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the delivery of positive drug ions (D+), such as ACh, from the chamber. For negatively charged ions, such as SNP, the current is reversed. Current is delivered by an iontophoretic device connected to a computer that controls iontophoretic settings and collects the data.

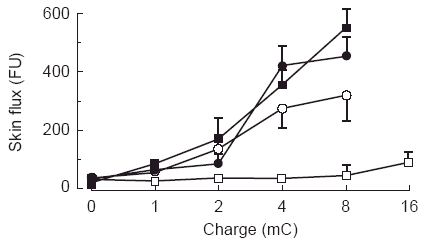

Figure 2.

Development of an inert vehicle for drug iontophoresis. Responses to saline (▪), tap water (•), distilled, de-ionised, h.p.l.c.-grade water (○), and 2% methylcellulose gel reconstituted in distilled, de-ionised, h.p.l.c.-grade water (□).

Subjects acclimatised to an ambient temperature of 22– 25° C for 30 min, and rested supine throughout the recordings. The skin was cleansed with an isopropyl alcohol swab at the beginning of acclimatisation, and left undisturbed for at least 10 min before attaching a perspex iontophoresis chamber (Moor Instruments Ltd, Millwey, Axminster, Devon, UK), using a double-sided adhesive ring, to the volar aspect of the forearm. A thermocouple was taped to an adjacent site, so that skin temperature could be monitored throughout and maintained above 32° C [15]. 0.25 ml vehicle (2% methylcellulose gel) or drug (ACh (Sigma Chemicals Ltd, Poole, Dorset, UK) or SNP (Nipride, Roche Pharmaceutical Products Ltd), both at 2% final concentration in 2% methylcellulose gel) was then injected into the iontophoresis chamber and a laser Doppler probe was inserted to measure flux continuously. Iontophoresis was controlled with a Moor Iontophoresis Controller 1 (Moor Instruments Ltd) which delivered currents of increasing duration and intensity (100 μA for 10 s; 200 μA for 10 s; 200 μA for 20 s; 200 μA for 40 s; and 200 μA for 80 s) such that charges of 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 mC were applied. Polarity of the current was reversed for ACh (positively charged) and SNP (negatively charged). Response periods were allowed after each charge (60 s for 1 and 2 mC, 90s for 4 mC, 120 s for 8 and 16 mC) which were sufficient for the response to plateau consistently at a maximum dilatation. This response was sustained for approximately 10 min after iontophoresis had ceased. The iontophoresis chamber was then removed and cleaned before the procedure was repeated on a neighbouring site with the next solution (drug or vehicle).

Mean flux, measured at the plateau of the response for each drug charge, was expressed in arbitrary flux units. Data were downloaded onto a personal computer for subsequent analysis (Moorsoft V4.241, Moor Instruments Ltd.).

In preliminary experiments, after completion of each sequence of charges, laser Doppler ‘biological zero’ values were recorded for 30 s during inflation of an upper arm cuff to 220 mm Hg. The range of laser Doppler biological zero values obtained was low (between 4.5 and 13.1 flux units; mean 7.5±0.3). These values are negligible in relation to the vasodilatation to iontophoresed drugs (Table 1; Figures 2 and 3). Therefore, biological zeros were not recorded in further experiments.

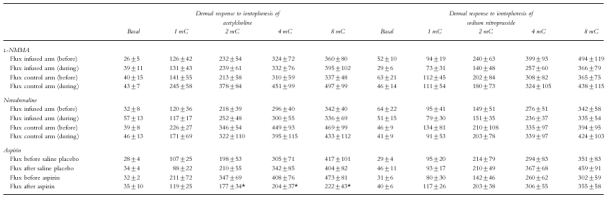

Table 1.

Iontophoretic responses to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside before and after brachial artery infusion of l-NMMA or noradrenaline, and before and after bolus intravenous injection of aspirin or saline placebo. Results for skin flux from each subject were averaged to give means±s.e.mean in arbitrary units of flux (FU). For the systemic aspirin study, flux was reduced after aspirin compared either with placebo or with flux before aspirin administration (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA).

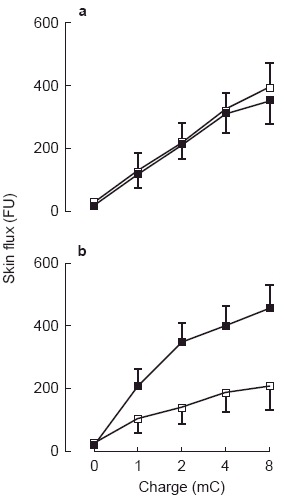

Figure 3.

a) Vasodilatation during iontophoresis of acetylcholine before (▪) and during (□) brachial artery infusion of l-NMMA. Units of flux are given as arbitrary flux units (FU). b) Vasodilatation during iontophoresis of acetylcholine before (▪), and 30 min after (□), intravenous injection of aspirin (600 mg). Reduction in flow by aspirin was significant by ANOVA (P < 0.01). Units of flux are given as arbitrary flux units (FU).

This protocol did not result in significant discomfort in any subject.

(ii) Forearm blood flow

The technique of venous occlusion plethysmography has been described in detail elsewhere [18, 19]. Briefly, subjects lay supine with their arms inclined at approximately 30° to improve venous drainage. Wrist cuffs were applied and, during the recording period, were inflated to 220 mm Hg to exclude the hand circulation from the measurements. Upper-arm congesting cuffs were inflated to 40 mm Hg and blood flow was recorded for 10 s followed by a 5 s refilling period. Multiple 10 s measurements were made over a three minute period and the slopes of the final five recordings averaged to determine forearm blood flow.

Study design

(i) Dermal vascular responses to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in the presence of l-NMMA or noradrenaline

Six subjects participated in a two-phase randomised study in which the dermal response to ACh and SNP were studied during brachial artery infusions of noradrenaline or l-NMMA. Phases were separated by at least 1 week. After acclimatisation as above, a 27 SWG steel cannula (Cooper's Needle Works, Birmingham, UK) was inserted into the brachial artery of the non-dominant arm, under local anaesthesia with 1% lignocaine. Physiological saline was infused at 1 ml min−1via the brachial artery cannula for 20 min to allow establishment of resting forearm blood flow. On one day, noradrenaline (Sanofi Winthrop Ltd) was then infused at incremental doses (60, 120, 240 and 480 pg min−1; each dose for 10 min at 1 ml min−1 [20]) via the brachial artery cannula until 40% reduction in forearm blood flow had been achieved. The dose of noradrenaline causing a 40% reduction in forearm blood flow was then infused for a further 30 min. On a separate day, after the 20 min infusion of saline, l-NMMA (Clin-Alfa) was infused at 4 μmol min−1 for 30 min. Iontophoresis of ACh and SNP was performed as above in both arms after the establishment of resting forearm blood flow and during the final 5 min of the l-NMMA and noradrenaline infusions. The order of iontophoresis was randomised.

(ii) Dermal vascular responses to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in the presence of aspirin

Six subjects participated in a two-phase randomised study in which the dermal response to ACh and SNP were studied before and after intravenous administration of either placebo or aspirin. Phases were separated by at least 2 weeks. After acclimatisation as above, a 21 SWG cannula was inserted under local anaesthesia using 1% lignocaine into the antecubital vein of the non-dominant arm. On one day, ACh and SNP were iontophoresed in random order before and 30 min after bolus intravenous injection of aspirin (600 mg in 5 ml water for injection; Laboratories Synthelabo, Paris, France) given over 5 min. On a separate day, ACh and SNP were iontophoresed in random order before and 30 min after bolus intravenous injection of 5 ml 0.9% saline placebo.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Analysis of iontophoretic response curves and forearm blood flow responses were by repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results

Iontophoresis reproducibility

In 10 healthy subjects studied twice, the protocol described above gave intra-individual and inter-individual coefficients of variation for maximal responses of 34±4 and 41±5% for ACh, and 34±4 and 29±3% for SNP, respectively.

Effect of l-NMMA and noradrenaline

l-NMMA caused a 43±2% reduction of forearm blood flow in the infused (4.4±1.3 to 2.4±0.8 ml 100 ml−1 min−1; P < 0.002) but not the control arm (3.6±0.8 to 3.6±0.5 ml 100 ml−1 min−1). Similarly, noradrenaline caused a 44±2% reduction in forearm blood flow in the infused (3.6±0.7 to 2.0±0.5 ml 100 ml−1 min−1; P < 0.001) but not in the control arm (2.6±0.4 to 2.7±0.6 ml 100 ml−1 min−1). These results confirm that the agents given were locally and not sytemically active.

Brachial artery infusion of l-NMMA or noradrenaline did not alter recordings of skin blood flow at baseline, and did not alter the vasodilator response to iontophoresis of ACh or SNP in either the infused or control arms (Table 1, Figure 3a). At the highest iontophoretic dose of ACh, flux was 396±102 flux units; 95% CI 134–658 during l-NMMA infusion; and 336±69 flux units; 95% CI 158–514 during noradrenaline infusion.

Effect of aspirin

Placebo injection had no effect on baseline skin blood flow or on the vasodilator response to iontophoresis of ACh or SNP (Table 1). However, administration of aspirin inhibited the vasodilator response to ACh (222±43 flux units at highest dose; 95% CI 111–332; Figure 3b), but did not affect the response to SNP (355±58 flux units; 95% CI 205–504; Table 1).

Discussion

Previous studies using iontophoresis for drug delivery to human dermal vessels have been limited by non-specific vasodilatation in response to the vehicles employed [17, 21]. There are a number of reasons for this. Saline and tap water contain ions which induce nociceptive and thermal axon reflexes, mediating release of vasoactive agents such as bradykinin and substance P [16, 22]. The use of high iontophoretic charges may exacerbate this, if it induces electrical arcing through ionic vehicle solutions. We have overcome these problems by developing an inert gel solution and using a protocol with low iontophoretic charges, whereby weal formation, pain, and the vasodilatation to vehicle alone are abolished. As a result, rather than having to correct for the non-specific responses to our vehicle [17], we have measured vasodilatation which is directly attributed to the drug administered.

Having established this technique, we have shown that the iontophoretic responses to ACh or SNP are not affected by noradrenaline-induced vasoconstriction or by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis with l-NMMA. The doses of noradrenaline and l-NMMA were matched to produce the same vasoconstriction in the forearm resistance circulation, which is principally determined by flow in skeletal muscle [18]. Despite this, they may not have produced the same preconstriction in dermal vessels. Unfortunately, laser Doppler is insufficiently sensitive to detect dermal vasoconstriction from baseline values (Table 1) [23]. However, if anything, preconstriction would be predicted to decrease rather than maintain cholinergic vasodilatation, and this was not observed with either preconstrictor. Our previous studies showed that l-NMMA induced basal vasoconstriction in thermoregulatory vessels of the finger pulp but not in nutritive vessels on the dorsum of the hand [19], suggesting that basal nitric oxide generation is not important in nutritive vessels. The current study supports this conclusion, demonstrating that nitric oxide synthase inhibition also had no effect on stimulated vasodilatation in nutritive vessels of the forearm. This suggests that ACh-induced vasodilatation in these vessels is mediated by a vasodilator other than nitric oxide.

In contrast, aspirin inhibited dermal vasodilatation in response to iontophoresis of ACh but did not affect the response to the non-endothelium dependent vasodilator SNP. This suggests that ACh induced dermal vasodilatation is mediated, at least in part, by synthesis of vasodilator prostanoids. This finding contrasts with a previous study in which oral aspirin was found to have no effect on ACh-induced dermal vasodilatation [17] but these investigators observed substantial vasodilatation with vehicle administration which they had to subtract from the response to ACh, so their measurements may not have been as reliable as the technique which we have developed. Although aspirin inhibits cholinergic vasodilatation in the skin of the forearm, it is not surprising that it has no effect on total forearm cholinergic vasodilatation [8] since the skin contributes only a small fraction of forearm flow when the hand is excluded [18]. In the present study, there was also an element of cholinergic vasodilatation which was not inhibited by aspirin (approximately 40%). The 600 mg dose of aspirin used here has been demonstrated to cause near total inhibition of prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis 30 min after administration which lasts for 6 h [24]. It seems likely, therefore, that dilator prostanoids are not the only mediators of the response to ACh in the skin. For example, the contribution of endothelium-dependent hyperpolarising factor has yet to be determined.

The goal of this work was to establish a non-invasive technique for the measurement of endothelial function in man. Iontophoresis would have advantages over intra-arterial infusions since it is non-invasive, and over flow-mediated vasodilatation measured by ultrasound [25] since it allows specific pharmacological testing in resistance rather than conduit vessels. However, despite our improvements to the technique, we found that the variability of the responses to ACh and SNP remains relatively high (>25%) so that, while it has been useful in studies of groups [26, 27], it is likely to be of limited value in the assessment of an individual patient. Also, since the response is not mediated by nitric oxide synthesis, this technique cannot replace the intra-arterial infusion of ACh in the assessment of endothelial function [8, 9, 11, 12]. Rather, it may complement it by assessing a different pathway of endothelium-dependent dilatation in a different vascular bed.

In summary, we have established a safe, easy to use, non-invasive technique for investigating dermal vasodilatation to acetylcholine by iontophoresis. The principal mechanism of this response is prostanoid-mediated. Thus, trans-dermal iontophoresis may complement the more invasive intra-arterial methods of investigating the relationships between endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Rodney Gush for his technical support, and to Moor Instruments Ltd, Millwey, Axminster, Devon EX13 5DT, for the loan of the iontophoresis and laser Doppler equipment. Dr Noon was supported by the Scottish Home and Health Department. Dr Hand was supported by an Allen Postgraduate Research Fellowship awarded by the University of Edinburgh. Dr Walker is a British Heart Foundation Senior Research Fellow.

References

- 1.Furchgott RF, Zawadski JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallance P, Collier J, Moncada S. Effects of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on peripheral arteriolar tone in man. Lancet. 1989;ii:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zellers TM, McCormick J, Wu Y. Interaction among ET-1, endothelium-derived nitric oxide, and prostacyclin in pulmonary arteries and veins. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H139–H147. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.1.H139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garland CJ, Plane F, Kemp BK, Cocks TM. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarisation: a role in the control of vascular tone. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beierwaltes WH, Schrijver S, Sanders E, Strand J, Romero JC. Renin release selectively stimulated by prostaglandin I2 in isolated rat glomeruli. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:F276–F283. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.243.3.F276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito S, Carretero OA, Abe K, Beierwaltes WH, Yoshanaga K. Effects of prostanoids on renin release from rabbit afferent arterioles with and without macula densa. Kidney Intl. 1989;35:1138–1144. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowienczyk PJ, Watts GF, Cockcroft JR, Ritter JM. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation of human forearm resistance vessels in hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet. 1992;340:1430–1432. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92621-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linder L, Kiowski W, Buhler FR, Lüscher TF. Indirect evidence for release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in human forearm circulation in vivo. Circulation. 1990;81:1762–1767. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.6.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Epstein SE. Abnormal endothelium-dependent relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treasure CB, Klein JL, Vita JA, et al. Hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy are associated with impaired endothelium-mediated relaxation in human coronary resistance vessels. Circulation. 1993;87:86–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calver AL, Collier JG, Moncada S, Vallance PJT. Effect of local intra-arterial NG-monomethyl-L-arginine in patients with hypertension: the nitric oxide dilator mechanism appears abnormal. J Hypertens. 1992;10:1025–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panza JA, Casino PR, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA. Role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in the abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1993;87:1468–1474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Salvetti A. Vasodilatation to acetylcholine in primary and secondary forms of human hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:929–933. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cockcroft JR, Chowienczyk PJ, Benjamin N, Ritter JM. Preserved endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1036–1040. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westerman RA, Widdop RE, Hannaford J, et al. Laser Doppler fluximetry in the measurement of neurovascular function. Australasian Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine. 1988;11:66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westerman RA, Low AM, Widdop RE, Neild TO, Delaney CA. Endothelial cell function in diabetic microangiopathy: problems in methodology and clinical aspects. Vol. 9. Front Diabetes, Basel: Karger; 1990. Non-invasive tests of neurovascular function in human and experimental diabetes mellitus; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris SJ, Shore AC. Skin blood flow responses to the iontophoresis of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in man: Possible mechanisms. J Physiol. 496:531–542. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb DJ. The pharmacology of human blood vessels in vivo. J Vasc Res. 1995;32:2–15. doi: 10.1159/000159072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noon JP, Haynes WG, Webb DJ, Shore AC. Local inhibition of nitric oxide generation in man reduces blood flow in the finger pulp but not in hand dorsum. J Physiol. 1996;490:501–508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker BR, Connacher AA, Webb DJ, Edwards CRW. Glucocorticoids and blood pressure: a role for the cortisol/cortisone shuttle in the control of vascular tone in man. Clin Sci. 1992;83:171–178. doi: 10.1042/cs0830171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner-Medwin JM, Taylor JY, Macdonald IA, Powell RJ. An investigation into variability in microvascular skin blood flow and the responses to transdermal delivery of acetylcholine at different sites in the forearm and hand. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 43:391–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Low A, Westerman RA. Neurogenic vasodilation in the rat hairy skin measured using a laser Doppler flowmeter. Life Sci. 1989;45:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noon JP, Evans CE, Haynes WG, Webb DJ, Walker BR. A comparison of techniques to assess skin blanching following topical application of glucocorticoids. Br J Dermatol. 134:837–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heavey DJ, Barrow SE, Hickling NE, Ritter JM. Aspirin causes short-lived inhibition of bradykinin-stimulated prostacyclin production in man. Nature. 1985;319:186–188. doi: 10.1038/318186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams MR, Robinson J, Sorensen KE, Deanfield JE, Celermajer DS. Normal ranges for brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation: A non-invasive ultrasound test of arterial endothelial function. J Vasc Invest. 1996;2:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris SJ, Shore AC, Tooke JE. Responses of the skin microcirculation to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in patients with NIDDM. Diabetologia. 1995;11:1337–1344. doi: 10.1007/BF00401767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan F, Litchfield SJ, McLaren M, Veale DJ, Littleford RC, Belch JJF. Oral L-arginine supplementation and cutaneous vascular responses in patients with primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1997;40:352–357. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]