Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to examine the pharmacokinetics of donepezil HCl and cimetidine separately, and in combination, following administration of multiple oral doses.

Methods

This was an open-label, randomized, three-period crossover study in healthy male volunteers (n = 19). During each treatment period, subjects received single daily doses of either donepezil HCl (5 mg), cimetidine (800 mg), or a combination of both drugs for 7 consecutive days. Pharmacokinetic comparisons were made between groups for the day 1 and day 7 profiles. Each treatment period was followed by a 3-week, drug-free washout period.

Results

On both day 1 and day 7, a statistically significant difference was observed between the donepezil and the donepezil+cimetidine groups in terms of the Cmax and AUC(0–24) values for donepezil. The combination group had an 11–13% greater Cmax and a 10% greater AUC(0–24) than the donepezil-only group. No significant difference was observed between the tmax of the two treatment groups on day 1, and no significant differences in tmax, t½ or the rate of drug accumulation (RA) were observed between the groups on day 7.

Cimetidine pharmacokinetics were essentially unchanged by co-administration of the two drugs. The donepezil+cimetidine treatment group had a 20% greater maximum cimetidine concentration (Cmax) than the cimetidine-only group (P = 0.001) on day 1, but not on day 7, and no difference was observed in any of the other pharmacokinetic parameters examined.

Conclusions

Co-administration of donepezil HCl (5 mg) and cimetidine (800 mg) did not produce clinically significant changes in the pharmacokinetic profiles of either drug.

Keywords: donepezil, cimetidine, drug–drug interaction, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor

Introduction

It is generally accepted that cognitive impairment and memory loss in patients with Alzheimer’s disease are related to the loss of cholinergic pathways in the cerebral cortex and other areas of the brain [1]. As a result, the clinical development of agents to counteract the symptoms of this disease has focused on those which enhance the function of the surviving cholinergic neurones within the affected areas of the central nervous system [1–3]. Donepezil HCl (also known as E2020 or Aricept®, the registered trademark of Eisai Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) is the first member of a new group of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the piperidines, that has been developed for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease [4–9]. Pre-clinical studies using both in vivo and in vitro models indicate that donepezil has a markedly greater selectivity for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) compared with butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), and a longer duration of inhibitory action than either physostigmine or tacrine [10].

The dose-related pharmacodynamic activity (AChE inhibition) demonstrated in pre-clinical and phase I studies [11] has been confirmed by clinical studies in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [12–15]. In these patients, treatment with donepezil was associated with statistically significant improvements in cognition and global function following administration of 5 or 10 mg day−1 doses [13–15]. The principal adverse events associated with donepezil were transient gastrointestinal disturbances, which included abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and occurred in a small percentage of patients. All of these events are consistent with an increase in cholinergic stimulation.

The pharmacokinetics of donepezil in healthy male volunteers are characterized by hepatic metabolism and slow plasma clearance (0.13 l h−1 kg−1) [16, 17]. The long half-life of approximately 70 h means that once-daily drug administration results in insignificant variability in plasma drug concentrations at steady state.

Cimetidine, an H2-receptor antagonist, is one of the most widely prescribed drugs for the treatment of duodenal ulcers, heartburn and gastritis. Cimetidine is known to have an inhibitory action on hepatic microsomal enzyme systems and has been shown to impair the metabolism of a number of commonly prescribed drugs, including anticoagulants, phenytoin, propranolol, some benzodiazepines and theophylline [18]. In addition, a recent study has shown that cimetidine significantly affects the pharmacokinetics of tacrine HCl [19], a cholinesterase inhibitor that is approved in the USA, France and Germany for the treatment of patients with mild–moderate Alzheimer’s disease. As a consequence, clinical consideration must be given to reducing the dose of tacrine when it is co-administered with cimetidine.

As donepezil is predominantly metabolized by the hepatic CYP-450 isoenzyme 3A4, and to a lesser extent 2D6, this study was designed to investigate whether the concurrent administration of donepezil and cimetidine would alter the plasma pharmacokinetic profile of either drug, following single- and multiple-dose administration.

Methods

Subjects

Entry into the study was confined to healthy, non-smoking, male volunteers between 18 and 45 years of age who were within 20% of ideal body weight, based on the Metropolitan Insurance Company Height and Weight Tables (1983). Subjects with evidence of clinically significant hepatic, gastrointestinal, renal, respiratory, endocrine, haematological, neurological, psychiatric or cardiovascular system abnormalities were specifically excluded from the study, as were those who had a known or suspected history of alcohol or drug misuse or a positive urine drug screen. None of the subjects had donated blood or had received investigational or prescription medications within 1 month of commencing trial medication.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Investigations Involving Human Subjects, Harris Laboratories, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Protocol

This was an open-label, randomized, three-period crossover study. The three randomized treatments administered in this study were (1) donepezil HCl, 5 mg tablet, (2) cimetidine, 800 mg tablet (Tagamet®, Burroughs Wellcome Laboratories), and (3) donepezil 5 mg+cimetidine 800 mg. Each treatment period was 7 days in duration and was followed by a 3-week, drug-free washout period. The dose of donepezil was chosen on the basis of results from clinical efficacy studies conducted in the USA, and the dose of cimetidine is the recommended starting therapeutic dose for treatment provided by the Physicians’ Desk Reference.

All volunteers were screened by medical history, ECG and laboratory and physical examinations ≤2 weeks prior to the start of the study. For each treatment period, subjects were admitted to the study site on the evening of day 0, at least 12 h prior to drug administration. Subjects were fasted overnight (8 h) prior to receiving their first dose of medication on the morning of day 1. Following drug administration, blood samples for analytical determinations were collected at specified intervals up to 120 h. Trough samples were taken each morning prior to drug administration (i.e. at 24, 48 and 72 h).

The subjects returned to the clinic as out-patients for the next four mornings to provide blood samples for pharmacokinetic analysis and to receive their daily dose of medication. They were re-admitted to the study site on the evening of day 6 and repeated the same schedule of events as on day 0. The subjects were discharged from the study site on the morning of day 8, 24 h after receiving their final dose of medication. They returned to the clinic as out-patients for the next six mornings to provide blood for post-dose pharmacokinetic analysis (to 168 h). During the course of the treatment period, subjects were not allowed to consume caffeine-containing food or drinks, and physical exercise was limited to normal walking.

Sample collection and analysis

Venous blood samples for the determination of donepezil and/or cimetidine concentrations in plasma were collected during each treatment period. Samples were collected 1 h prior to drug administration, and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h post-dose on days 1 and 7. Additional samples were taken 144 and 168 h after the last dose of medication on day 7 of each treatment period.

Immediately after collection, the blood samples were placed on ice and centrifuged for 15 min (2000 g at 4° C). Plasma was then removed and transferred into polypropylene tubes which were stored upright at −20° C until analysis. Plasma concentrations of donepezil (hydrochloride salt) were determined using a specific high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method with UV detection [20]. Cimetidine was analysed using a standard reversed-phase HPLC method with UV detection. The limits of detection for these assays were 2 ng ml−1 for donepezil and 0.1 μg ml−1 for cimetidine.

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Characterization of donepezil and/or cimetidine pharmacokinetics for each treatment phase was done by analysing blood samples collected over a 120-h period following initial dose administration, and a 168-h period following final dose administration.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for both drugs were estimated by a non-compartmental method. Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time at which it occurred (tmax) were recorded from the observed values, and the terminal disposition phase for donepezil and cimetidine was identified by visual inspection of each subject’s log concentration–time curve. The terminal disposition rate constant (λz) was estimated to be −2.303 times the slope of the best-fit linear regression line of the terminal phase. The terminal half-life (t½) was calculated as 0.693/λz, and the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC(0–24)) was estimated using the trapezoidal rule. The accumulation ratio (RA) was defined as AUC(0–24) on day 7 divided by AUC(0–24) on day 1.

Statistical analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters for all three treatment phases were calculated following both single-dose administration on day 1 and day 7. An analysis of variance model (ANOVA), accounting for the effects of treatment, period, sequence and subject, was used to compare these parameters between days and between treatment periods. The type III sums of squares for all model effects was used to determine statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Results

Subjects

A total of 19 subjects were enrolled into the trial and 18 successfully completed all three treatment phases. They ranged in age from 19 to 42 years (mean 28.7 years); their heights ranged from 170 to 190 cm (mean 179.4 cm) and their body weights from 64.0 to 85.2 kg (mean 75.5 kg). All study subjects were Caucasian. The one subject who did not complete the study was withdrawn because he was unable to comply with the dosing schedule.

Pharmacokinetics of donepezil

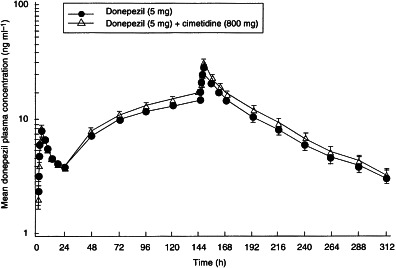

Mean plasma donepezil concentrations were calculated per time-point for each donepezil treatment group (donepezil alone, donepezil+cimetidine). A time–concentration plot of these data is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The effect of concomitant administration of donepezil (5 mg) and cimetidine (800 mg) once daily for 7 days on the mean (±SE) plasma concentration–timeprofile of donepezil in healthy male volunteers: 24-h profiles were conducted following dose administration on day 1 and day 7.

On day 1, a statistically significant difference was observed between the donepezil and the donepezil+cimetidine groups in terms of Cmax (P = 0.001) and AUC(0–24) (P = 0.032). The donepezil+cimetidine group had a 13% greater Cmax (7.8 ng ml−1 versus 6.8 ng ml−1) and a 10% greater AUC(0–24) (112 ng h ml−1 versus 102 ng h ml−1) than the donepezil-only group (Table 1). The coefficients of variation were 10.4% and 12.2% for Cmax and AUC(0–24), respectively. No significant difference was observed between tmax of both groups. No significant sequence effects were observed.

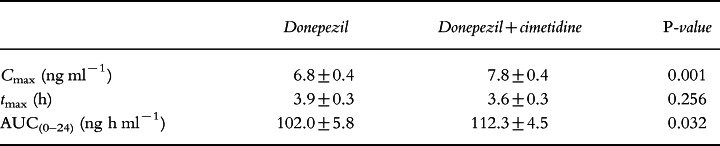

Table 1.

Donepezil pharmacokinetic parameters on day 1 (mean±SE).

On day 7, a statistically significant difference was again observed between the donepezil and the donepezil+cimetidine treatment groups in terms of Cmax (P = 0.0002) and AUC(0–24) (P = 0.0001). As shown in Table 2, the donepezil+cimetidine group had an 11% greater Cmax (29.9 ng ml−1 versus 26.6 ng ml−1) and a 10% greater AUC(0–24) (526.9 ng h ml−1 versus 472.3 ng h ml−1) than the donepezil-only group. The coefficients of variation were 7.0% and 6.0% for Cmax and AUC(0–24), respectively. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in tmax, t½ or RA. No significant sequence effects were observed.

Table 2.

Donepezil pharmacokinetic parameters on day 7 (mean±SE).

All differences observed in the pharmacokinetic parameters of the donepezil and the donepezil+cimetidine groups on days 1 and 7 were well below the range (±20%) suggested by the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines as indicating clinical relevance.

Pharmacokinetics of cimetidine

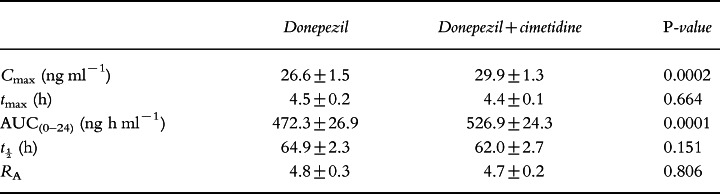

Mean plasma cimetidine concentrations were calculated per time-point for each cimetidine treatment group (cimetidine alone, donepezil+cimetidine). A time–concentration plot of these mean data is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The effect of concomitant administration of donepezil (5 mg) and cimetidine (800 mg) once daily for 7 days on the mean (±SE) plasma concentration–-time profile of cimetidine in healthy male volunteers: 24-h profiles were conducted following dose administration on day 1 and day 7. Concentrations of cimetidine were below the detectable limit, in one or both treatment groups, at 48, 192 and 16 h.

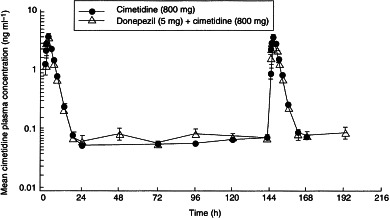

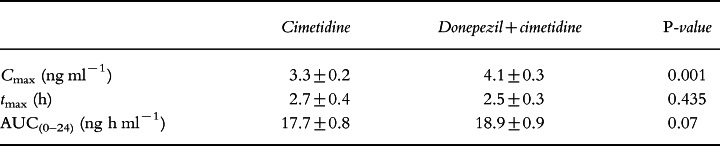

Results of the cimetidine pharmacokinetic analysis are summarized in Table 3. On day 1, a statistically significant difference was observed between Cmax (P = 0.001) of the cimetidine-only and the donepezil+cimetidine groups. The latter had a 20% greater Cmax (4.1 ng ml−1 versus 3.3 ng ml−1) than the cimetidine-only group. No statistically significant difference was observed in any of the other parameters between these groups.

Table 3.

Cimetidine pharmacokinetic parameters on day 1 (mean±SE).

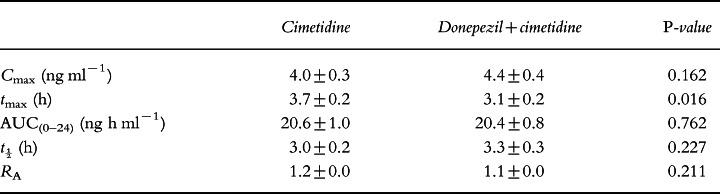

No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for Cmax, AUC(0–24), t½ or RA on day 7 (Table 4). The cimetidine-only group had a statistically significantly greater tmax (P = 0.016) than the combination group (3.7 h versus 3.1 h, respectively). No significant sequence effects were observed.

Table 4.

Cimetidine pharmacokinetic parameters on day 7 (mean±SE).

All differences observed in the pharmacokinetic parameters of the cimetidine and the donepezil+cimetidine treatment groups on days 1 and 7 were also well below the range (±20%) suggested for clinical relevance.

Safety

Both treatments were well tolerated and there were no clinically significant changes in vital signs, clinical laboratory or ECG parameters during the course of the study. Those adverse events that were reported were transient and dissipated with continued drug administration. All were mild to moderate in intensity.

Discussion

Cimetidine has been shown to reduce the hepatic metabolism of some drugs, including anticoagulants, phenytoin, propranolol, some benzodiazepines and theophylline [18], apparently through the inhibition of hepatic microsomal enzyme systems. As donepezil is predominantly metabolized in the liver, the concurrent administration of cimetidine might affect the plasma concentration of donepezil.

The concurrent administration of both single and multiple doses of donepezil (5 mg) and cimetidine (800 mg) resulted in an increase in the plasma levels of donepezil compared with the single- and multiple-dose administration of donepezil alone. This change in donepezil plasma concentration was reflected by increases in both Cmax (11–13%) and AUC(0–24) (10%). There was no difference in the tmax values of the treatment groups on either days 1 or 7. In addition, t½ and the rate of donepezil accumulation in plasma were similar for both the donepezil and the donepezil+cimetidine treatment groups after 7 days of drug administration. This suggests that plasma concentrations of donepezil remain consistent and predictable, and are not changed significantly in the presence of cimetidine.

Although these results demonstrate that the metabolism of donepezil is decreased by the presence of cimetidine, it is unclear whether the metabolism of the drug is altered in such a way as to produce a changed pattern of metabolites. As the metabolites of donepezil are essentially clinically inactive (due both to low plasma concentrations as well as an inability to cross the blood–brain barrier), it is unlikely that even a substantial change in the metabolic processing of the drug would result in either a modification of drug effect or an increase in adverse events.

Cimetidine pharmacokinetics remained essentially unchanged by the concurrent administration of donepezil. Although there was a significantly greater Cmax for the donepezil+cimetidine group on day 1, and a significantly greater tmax for the cimetidine-only group on day 7, these changes were inconsistent and there were no specific trends or changes in cimetidine pharmacokinetics between the two treatment groups. This lack of effect on cimetidine pharmacokinetics was anticipated, and is consistent with the results from in vitro studies with donepezil (Aricept® US package insert, 1998). Isoform-selective substrate studies were conducted in human liver microsomes and the concentrations of donepezil required for 50% inhibition (IC50) of CYP-450 enzymes 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6 and 3A4 were determined. All IC50 values were greater than 100 μm. In addition, the mean ki values for CYP-3A4 and CYP-2D6 were calculated to be 131 μm and 47 μm, respectively. Clinical studies have shown that the steady-state Cmax for the 10 mg dose of donepezil is approximately 164 nm. Since it is anticipated that therapeutic concentrations of donepezil are more than 280-fold lower than the lowest ki value obtained with CYP-2D6 and almost 800-fold lower than the ki observed with CYP-3A4, it is expected that donepezil will not inhibit the metabolism of other drugs metabolized by these or any other CYP-450 isoenzymes.

In conclusion, it must be noted that although the increases in donepezil Cmax and AUC(0–24) were statistically significant when donepezil and cimetidine were administered concurrently, they were well below the threshold for changes in plasma drug concentration (±20%) considered to be clinically relevant by the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines. In addition, it should be noted that the accumulation of donepezil in plasma over time was not different between the two groups, demonstrating that donepezil clearance is the same in the presence or absence of cimetidine. Together, these results suggest that the concurrent administration of these drugs in clinical practice will not require a modification in dosing.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of Dr James Kisicki, Harris Laboratories Inc, 624 Peach Street, Box 80827, Lincoln, NE 68501, USA, who conducted this clinical trial, and the Institutional Review Board of Harris Laboratories, who reviewed and approved the study and protocol.

References

- 1.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Clarke AW, Coyle JT, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann Neurol. 1981;10:122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giacobini E. Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease: new drugs and novel strategies. Prog Brain Res. 1993;98:447–454. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker RE. Therapy of the cognitive deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: the cholinergic system. In: Becker R, Giacobini E, editors. Cholinergic Basis for Alzheimer Therapy. Boston: Birkhäuser; 1991. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardozo MG, Iimura Y, Sugimoto H, Yamanishi Y, Hopfinger AJ. QSAR analysis of the substituted indanone and benzylpiperidine rings of a series of indanone-benzylpiperidine inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. J Med Chem. 1992;35:584–589. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardozo MG, Kawai T, Iimura Y, Sugimoto H, Yamanishi Y, Hopfinger AJ. Conformational analysis and molecular shape comparisons of a series of indanone-benzylpiperidine inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. J Med Chem. 1992;35:590–601. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimoto H, Iimura Y, Yamanishi Y, Yamatsu K. Synthesis and anti-acetylcholinesterase activity of 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-indanon-2-yl)methyl]piperidine hydrochloride (E2020) and related compounds. Biorg Med Chem Lett. 1992;2:871–876. doi: 10.1021/jm00024a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pang YP, Kozikowski AP. Prediction of the binding site of 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-indanon-2-yl] methyl] piperidine in acetylcholinesterase by docking studies with the SYSDOC program. J Comput Aided Mol Design. 1994;8:683–693. doi: 10.1007/BF00124015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanishi Y, Ogura H, Kosasa T, Araki S, Sawa Y, Yamatsu K. Inhibitory action of donepezil, a novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, on cholinesterase. Comparison with other inhibitors. In: Nagatsu T, Fisher A, Yoshida M, editors. Basic, Clinical, and Therapeutic Aspects of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nochi S, Asakawa N, Sato T. Kinetic study on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-indanon)-2-yl]methylpiperidine hydrochloride (E2020) Biol Pharm. 1995;18:1145–1147. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers SL, Yamanishi Y, Yamatsu K. E2020—the pharmacology of a piperidine cholinesterase inhibitor. In: Becker R, Giacobini E, editors. Cholinergic Basis for Alzheimer Therapy. Boston: Birkhäuser; 1991. pp. 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers SL, Cooper NM, Sukovaty R, Pederson JE, Lee JN, Friedhoff LT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of donepezil HCl following multiple oral doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):7–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman K. Pharmacodynamics of oral E2020 and tacrine in humans: novel approaches. In: Becker R, Giacobini E, editors. Cholinergic Basis for Alzheimer Therapy. Boston: Birkhäuser; 1991. pp. 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT the Donepezil Study Group. The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a US multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia. 1996;7:293–303. doi: 10.1159/000106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT the Donepezil Study Group. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;50:136–145. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers SL, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT the Donepezil Study Group. Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer’s disease: a 15-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1021–1031. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mihara M, Ohnishi A, Tomono Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics of E2020—a new compound for Alzheimer’s disease, in healthy male volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1993;31:223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi A, Mihara M, Kamakura H, et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of E2020, a new compound for Alzheimer’s disease, in healthy young and elderly subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33:1086–1091. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knodell RG, Browne DG, Gwozdz GP, Brian WR, Guengerich FP. Differential inhibition of individual human liver cytochrome P-450 by cimetidine. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1680–1691. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90408-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forgue ST, Reece PA, Sedman AJ, de Vries TM. Inhibition of tacrine oral clearance by cimetidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:444–449. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JW, Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT, Stiles MR, Cooper NM. Validation and application of an HPLC method for the determination of 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-indanon)-2-yl] methyl piperidine HCl (E2020) in human plasma. Pharm Res. 1992;9:350. [Google Scholar]