Abstract

UL9 is a multifunctional protein required for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) replication in vivo. UL9 is a member of the superfamily II helicases and exhibits helicase and origin-binding activities. We have previously shown that mutations in the conserved helicase motifs of UL9 can have either a transdominant or potentiating effect on the plaque-forming ability of infectious DNA from wild-type virus (A. J. Malik and S. K. Weller, J. Virol. 70:7859-7866, 1996). In this paper, the mechanisms of transdominance and potentiation are explored. We show that the motif V mutant protein containing a G to A substitution at residue 354 is unstable when expressed by transfection and is either processed to a 38-kDa N-terminal fragment or degraded completely. The overexpression of the MV mutant protein is able to influence the steady-state protein levels of wild-type UL9 and to override the inhibitory effects of wild-type UL9. Potentiation correlates with the ability of the UL9 variants containing the G354A mutation to be processed or degraded to the 38-kDa form. We propose that the MV mutant protein is able to interact with full-length UL9 and that this interaction results in a decrease in the steady-state levels of UL9, which in turn leads to enhanced viral infection. Furthermore, we demonstrate that inhibition of HSV-1 infection can be obtained by overexpression of full-length UL9, the C-terminal third of the protein containing the origin-binding domain, or the N-terminal two-thirds of UL9 containing the conserved helicase motifs and the putative dimerization domain. Our results suggest that transdominance can be mediated by overexpression, origin-binding activity, and dimerization, whereas potentiation is most likely caused by the ability of the UL9 MV mutant to influence the steady-state levels of wild-type UL9. Taken together, the results presented in this paper suggest that the regulation of steady-state levels of UL9 may play an important role in controlling viral infection.

The UL9 gene is required for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) replication in vivo (6, 9). The UL9 protein is a dimer in solution and exhibits helicase, ATPase, and origin-binding activities (8, 13). UL9 is believed to play a key role in the initiation of HSV-1 replication by binding the HSV-1 origin of replication via its C-terminal domain and unwinding it in the presence of ATP and ICP8, the HSV-1 single-stranded DNA binding protein. It is likely that UL9 plays an important role in the assembly of the viral replisome (10, 20, 26, 41) through its interactions with other viral replication proteins (7, 28, 29).

UL9 is a member of the superfamily II helicases (14). The conserved helicase motifs that are characteristic of this superfamily are positioned within the N-terminal domain of the protein (14). Genetic studies have previously shown that conserved residues within the helicase motifs are essential for HSV-1 replication in vivo; most engineered motif mutants fail to complement the growth of hr94, a UL9 null virus (24, 27). Furthermore, biochemical analysis showed a correlation between the failure to complement hr94 and the lack of helicase activity (25), indicating that helicase activity is essential for UL9 function. Interestingly, a truncated form of UL9 originating from a unique transcript within the UL9 open reading frame designated UL8.5 or OBPC has been observed (4, 5). OBPC encompasses the 480 C-terminal amino acids of UL9. It is able to bind the origin of replication and localizes to the nucleus, but its significance for the biology of the HSV-1 is not well understood.

Several lines of evidence indicate that overexpression of UL9 can inhibit HSV-1 infection. We previously showed that cell lines containing a low copy number of the wild-type UL9 gene could efficiently complement hr94. whereas cell lines harboring a high copy number exhibited lower levels of complementation (21). In addition, cell lines harboring a high copy number of the UL9 gene were found to inhibit wild-type HSV-1 infection (21). Furthermore, the cotransfection of wild-type infectious DNA with an excess of plasmid encoding wild-type UL9 reduced the number of plaques observed compared to transfection of wild-type infectious DNA alone (2, 23, 32). The inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 overexpression is mediated at least in part by the origin-specific DNA binding function of UL9, harbored in the C-terminal domain (UL9 CTD). In a plaque reduction assay, UL9 CTD severely reduces the efficiency of plaque formation (2, 23, 32) and is thus considered transdominant (dominant negative). The OB mutation which disrupts the origin-binding activity of UL9 reverses the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 as well as the transdominant effect of UL9 CTD (2, 23, 32).

The inhibitory properties of the overexpressed wild-type UL9 are consistent with a model in which HSV-1 DNA replication occurs in two steps or stages (6, 26, 34, 41). According to this model, early in infection HSV-1 replication initiates by a UL9-dependent process at one or more origins of replication (stage I). Later in infection, replication proceeds in an origin-independent manner (stage II). We have proposed that, if UL9 remains bound to the origin of replication late in infection, it may inhibit the transition between stage I and stage II (25, 26). Consistent with this model, studies with temperature-sensitive UL9 mutants indicate that UL9 is essential for the early stages of HSV-1 replication and appears to be dispensable for the later ones (6). According to this scenario, we speculate that it may be necessary to downregulate the levels of UL9 protein during stage II in order for infection to proceed.

The characterization of transdominant (dominant negative) mutants is a widely employed genetic approach to gain insight into protein function (15). Mutations in UL9 helicase motifs I, Ia, II, and VI were previously shown to be transdominant in a plaque reduction assay (23, 24). UL9 mutant proteins bearing mutations in helicase motifs I, Ia, II, and VI are able to dimerize and bind the origin of replication but are defective for helicase activity (24, 25). We proposed that the transdominance exhibited by these mutants is a result of inhibition of HSV-1 replication at stage I, due to lack of helicase activity, and inhibition of the transition between stage I and stage II, due to overexpression of protein capable of binding the origin, as proposed above for wild-type UL9.

In contrast to the transdominant mutations in helicase motifs I, Ia, II, and VI, a mutation in motif V (G354A) was found to confer a potentiating phenotype. When cells were cotransfected with this mutant and wild-type infectious DNA, the plaque number increased compared to transfection with wild-type infectious DNA alone (23). Interestingly, no stable mutant protein could be detected in the transient transfection-Western blot assay (23, 27). Intrigued by the ability of an apparently unstable protein to potentiate HSV-1 infection, we sought to further understand the mechanism of potentiation. In this paper, we show that the ability of the UL9 G234A (motif V) mutation to potentiate HSV-1 infection inversely correlates with protein stability. The overexpression of UL9-MV is able to reduce the steady-state wild-type UL9 protein levels and override its inhibitory effects. Furthermore, we report that a fragment consisting of the N-terminal 535 amino acids of UL9 is also transdominant. Based on the genetic and biochemical properties of UL9 helicase motif mutants, we propose a model for the mechanism of transdominance and potentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and materials.

All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. The pFastBac vector was purchased from Gibco-BRL; the pCDNA-1 and pCDNA-3 vectors were from Invitrogen. Supplemented Grace's medium and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Gibco-BRL; fetal calf serum was from Gemini Bioproducts Inc.

Viruses and cells.

HSV-1 strain KOS was used as the wild-type virus in all assays. hr94, a UL9 lacZ insertion mutant, was described previously (21). Vero cells (American Type Culture Collection) and 2B-11, a Vero-derived cell line stably transfected with wild-type UL9 (21), were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as described previously (42).

Spodoptera frugiperda Sf21 insect cells were maintained in serum-free medium containing 0.1 mg of streptomycin per ml and 100 units of penicillin per ml. Escherichia coli DH5α cells were used for plasmid amplification. DH10Bac competent cells (Gibco-BRL) were used for bacmid packaging and propagation.

Antibodies.

Several anti-UL9 antibodies were used in this study: R250 (a kind gift from M. Challberg, National Institutes of Health) is a polyclonal antibody that recognizes the C-terminal 10 amino acids of UL9; 17B is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the N-terminal 35 amino acids of UL9 (22); and RH7 (a kind gift from D. Tenney, Bristol Meyers Squib) was raised against a glutathione S-transferase fusion with the UL9 C-terminal domain (residues 535 to 851).

The polyclonal anti-UL6 antibody was described previously (18). Anti-AU1 tag antibody was purchased from Babco (Berkeley, Calif.), and polyclonal anti-ICP8 antibody was a kind gift from W. Ruyechan, State University of New York, Buffalo, N.Y. (36). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and Texas red-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibodies were used as secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence analysis. Commercially available antitubulin antibody (Sigma) was used in Western blot analysis to monitor sample loading. Anti-His tag India probe (Pierce) was used to detect His-tagged UL9 fusions.

Plasmids.

The pFastBac transfer vectors were used to generate recombinant baculoviruses bearing the C-terminal 317 amino acids of UL9 (pFastBac-UL9-CT) and the N-terminal 535 amino acids of UL9 (pFastBac-UL9-NT). The BamHI- and EcoRI-digested PCR product containing the C terminus (UL9-CT) was inserted in the pFastBac plasmid to generate pFastBac-UL9-CT. The PCR product was amplified by stepdown PCR (3) with pFastBac-UL9-WT-expressing plasmid as a template and the following oligonucleotides: BamHI-UL9Δ1-534 (5′-GCCGAGGTGGATCCATGGATCCCGAGGCGTCGCTGCCGGCCCA-3′) and 3′PCL-pFastBac (5′-GATTATGATCCTCTAGTACTTCTC-3′). The pFastBac-UL9-NT plasmid was generated by cloning a BamHI- and EcoRI-digested PCR product containing UL9-NT into the pFastBac plasmid. The UL9-NT PCR fragment was amplified by stepdown PCR with the pFastBac-UL9-WT plasmid as a template and the following oligonucleotides: UL9Δ535-851-EcoRI (5′-GCCGAGGTGAATTCTTACTACCGGCACCGCAGCTCCCGTAGATCG-3′) and 5′PCL-pFastBac (5′-GATTATTCATACCGTCCCACCATC-3′).

The pCDNA3-UL9-WT plasmid, expressing wild-type UL9 under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter, was generated by inserting a BamHI-EcoRI fragment containing the wild-type UL9 gene from pFastBac-UL9-WT (25) into the pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). The pCDNA3-UL9-MI plasmid, carrying the K87A mutation in helicase motif I, was generated by inserting a BamHI-EcoRI fragment from pCDNA1-UL9-MI into the pCDNA3 vector. The pCDNA3-UL9-MV plasmid was generated by replacing the wild-type UL9 sequence in pCDNA3-UL9-WT with an AscI-EcoRI fragment containing the G354A mutation from p6UL9-MV (27). The pCDNA3-UL9-MI/MV double mutant was generated by subcloning an AscI-EcoRI fragment containing the G354A mutation from p6UL9-MV into pCDNA3-UL9-MI, replacing the corresponding wild-type fragment. pCDNA3-UL9 NTD and pCDNA-UL9-CTD were generated by inserting the BamHI-EcoRI fragment from pFastBac-UL9 NTD and pFastBac-UL9-CTD, respectively, into the pCDNA3 vector.

The pCDNA3-UL9Δ322-851, pCDNA3-UL9Δ355-851-MV, and pCDNA3-UL9Δ450-851 plasmids were generated by inserting the AscI- and EcoRI-digested PCR fragments containing the corresponding truncations into pCDNA3-UL9-WT, replacing the wild-type fragment. All PCR fragments were generated by stepdown PCR with the pFastBac-UL9-WT plasmid as the template and OligoI (5′-GCGGAGTCGGGAGATCCTCTGGGG-3′) as the upstream primer. The pCDNA3-UL9Δ450-851-MV truncation was generated with the same procedure except that the p6UL9-MV plasmid was used as a template in the PCR. The specific downstream oligonucleotides used to generate the above truncations were UL9Δ322-851 (5′-GCCGAGGTGAATTCTCATTAGTCCGTAAACTGACGGCAGAACCGGGCCAC-3′), UL9Δ355-851-MV (5′-GCCGAGGTGAATTCTCATTAGGCCACCGTTACGACCGTCGTGTATATAACCACGCG-3′), and UL9Δ450-851 (5′-GCCGAGGTGAATTCTCATTAGCATGCCGACGCGTCACAGCGCCCCTTGAACC-3′). The pUL9Eco plasmid, cont-aining UL9 under the control of its natural promoter, was generously provided by P. Schaffer (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine). J. Nellissery kindly provided the pCDNA3-UL6 plasmid. The p6UL9-119b plasmid, containing the UL9 gene under the control of the ICP6 promoter, was described previously (27).

The pCDNA3-UL9-NT-AU1 plasmid was generated by subcloning an AscI- and NotI-digested PCR product into pCDNA3-UL9-WT, replacing the corresponding wild-type fragment. The PCR product was generated by stepdown PCR with the pFastBac-UL9-WT plasmid as a template, OligoI (5′-GCGGAGTCGGGAGATCCTCTGGGG-3′) as the upstream primer, and UL9-NT-AU1 (5′-GCCGGCTTCTGCGGCCGCTCACTATATATAGCGATACGTATCATCCCGGCACCGCAGCTCCCGTATG-3′) as the downstream primer. The nucleotide sequence encoding the AU1 tag is underlined. The cloning procedure resulted in the addition of the AU1 tag (DTYRYI) at the C terminus of UL9-NT.

The pCDNA3-AU1-UL9 plasmid was created by inserting a BamHI-EcoRI fragment containing the wild-type UL9 gene into the pCDNA3-AU1 vector, resulting in the addition of an AU1 tag at the N terminus of UL9. The pCDNA3-AU1 vector was generated by ligation of an AU1-containing linker in the polycloning site via the HindIII and BamHI sites. The AU1-containing linker was created by annealing the BM-HB-AU1-T (5′-AGCTTACCATGGATACGTATCGCTACATAG-3′) and BM-HB-AU1-B (5′-GATCCTATGTAGCGATACGTATCCATGGTA-3′) oligonucleotides. The nucleotide sequence encoding the AU1 tag is underlined.

Generation of recombinant baculoviruses expressing UL9 variants.

Recombinant baculoviruses (Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis baculoviruses) expressing wild-type (25) or mutant UL9 variants were generated with the pFastBac (Gibco-BRL) system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell lysates.

Two types of mammalian cell lysates were used in this study. Regular cell lysates were obtained from one 60-mm2 plate which was washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing a Sigma protease inhibitor cocktail, harvested, and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer, resulting in a total of 300 μl of lysate. The lysates were boiled and analyzed by Western blot analysis. Concentrated cell lysates were prepared from one 60-mm2 plate, which was harvested and resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, resulting in a total of 60 μl of five-fold-concentrated lysate. The samples were cup-sonicated twice (Sonicator Ultra Processor XL; Misonix, Inc.; power setting 9 for 1 min), boiled, and analyzed.

Transient transfection-complementation assay.

The transient transfection-complementation assay was performed as described previously (21, 27). Each experiment was repeated three times, and the mean complementation index was calculated.

Plaque reduction assay.

The plaque reduction assay was performed as described previously (23). In brief, Vero cells in 60-mm2 plates at 50% confluence were cotransfected with wild-type HSV-1 infectious DNA (strain KOS) and the plasmid of interest (at a ratio of 1:10) with Lipofectamine Plus (Gibco), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The plates were overlaid with methylcellulose and incubated until plaques were observed. Plaques were stained with crystal violet and counted. Each experiment was performed three times, and the mean number of plaques and the standard deviation were calculated.

Immunofluorescent microscopy.

Vero cells were transfected with 2 μg of the plasmid of interest with Lipofectamine Plus (Gibco) and processed for immunofluorescence 18 h posttransfection. The transfected cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained as described previously (22) except that all procedures were performed at room temperature and phosphate-buffered saline was supplemented with 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 to reduce cell detachment. The primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: 17B, undiluted; RH7, 1:100 dilution; anti-ICP8, 1:400 dilution; anti-AU1, 1:500 dilution. The secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200. Images were taken with an Olympus BX60 microscope (at 100× magnification) equipped with a Hamamatsu Orca digital camera (model C4742-95) and Open Lab software (Improvisions). Images were processed and arranged with Adobe Photoshop 6.0 and Adobe Illustrator 7.0 software.

RESULTS

The UL9 helicase motif mutants were classified as transdominant or potentiating based on a plaque reduction assay in which cells were cotransfected with wild-type infectious DNA and an excess of UL9-encoding plasmid. The number of plaques observed in cells transfected with infectious DNA only was normalized to 100 (23, 39). Overexpression of wild-type UL9 slightly reduced the number of plaques in this assay (60 compared to 100); therefore, wild-type UL9 is considered inhibitory. Mutants whose overexpression resulted in significant reduction of the plaque number were classified as transdominant. For instance, in cells transfected with motif I, Ia, II, and VI mutants, the number of plaques dropped to 10 to 15. In contrast, mutants whose overexpression led to increased plaque number were classified as potentiating. In cells transfected with the motif V mutant, the plaque number increased to 180 (23).

It was shown previously that the motif V mutant protein was undetectable in mammalian cells transiently transfected with a mammalian expression vector under the control of the ICP6 promoter (23). No protein could be detected in immunoblots of cell lysates from UL9-MV-transfected cells with any of the available anti-UL9 antibodies (17B, raised against the extreme N terminus; R250, recognizing the extreme C terminus; or RH7, raised against the whole C-terminal domain) (23). In addition, a mutant carrying the motif V mutation and the OB mutation (a 4-amino-acid insertion after residue 591 in the C-terminal domain of UL9 that abolishes the origin-specific DNA function) was even more potentiating than the motif V mutant alone; the number of plaques in this case was increased to 220 (23). These results indicated that the motif V mutant was capable of influencing the outcome of a viral infection and thus must be expressed, at least transiently.

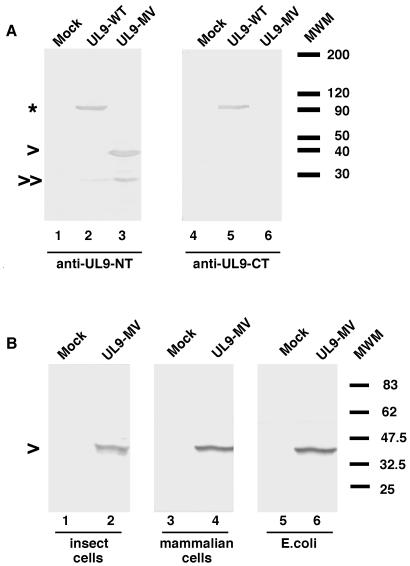

N-terminal fragment(s) but not full-length UL9-MV protein can be detected in heterologous expression systems.

In order to determine if the motif V mutant protein could be detected in heterologous expression systems, UL9-MV was expressed in insect cells with recombinant baculoviruses. Cell lysates of insect cells infected with the recombinant virus bearing wild-type UL9 or the UL9-MV mutant were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies which recognize the extreme N terminus (17B) or the extreme C terminus (R250) of the UL9 protein. Both antibodies detected full-length wild-type UL9 protein (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 5, respectively). Consistent with our previous findings in mammalian cells (23), no full-length UL9-MV protein was observed with 17B or R250 antibodies (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 6, respectively). Surprisingly, the 17B antibody was able to detect two fragments of approximately 38 kDa (marked with an arrowhead) and 30 kDa (marked with two arrowheads). No fragments were detected with the anti-C terminus antibody (R250) (Fig. 1A, lane 6). The relative amount of the 30-kDa fragment varied between different sample preparations, suggesting that it may be a degradation product of the 38-kDa fragment.

FIG. 1.

N-terminal fragment but not full-length UL9-MV protein is detected in insect, mammalian, and bacterial cells expressing UL9-MV. (A) Western blot analysis of cell lysates of insect cells infected with baculovirus expressing wild-type UL9 or UL9-MV with the 17B antibody, recognizing the N-terminal 35 residues of UL9 (lanes 1 to 3), or the R250 antibody, recognizing the far C terminus of UL9 (lanes 4 to 6). Full-length UL9 is marked with an asterisk, and the N-terminal UL9 fragments are marked with single and double arrowheads. The molecular size markers (10-kDa protein ladder from Gibco) are depicted on the right. (B) Western blot analysis of cell lysates of insect (lanes 1 and 2), mammalian (lanes 3 and 4), and bacterial (lanes 5 and 6) cells expressing the UL9-MV mutant. The 17B anti-UL9 antibody was used for detection in lanes 1 to 4. The anti-His tag India probe was used for detection in lanes 5 and 6. Broad Range (New England Biolabs) prestained molecular size markers are depicted on the right.

We next asked whether the appearance of the N-terminal fragments in insect cells but not in mammalian cells reflects different expression levels and/or stability in these two types of cells. In order to determine if our previous failure to detect UL9-MV was due to expression levels, we cloned the UL9-MV mutant in a mammalian expression vector (pCDNA3; Invitrogen) under the control of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter, a strong constitutive promoter. Vero cells were transfected with the pCDNA3-UL9-MV plasmid, and the cell lysates were assayed for the presence of UL9-MV protein or UL9-MV fragments. As previously seen with vectors with the ICP6 promoter (23, 27), no protein species were detected with any of the anti-UL9 antibodies (data not shown), but when concentrated lysates of cells transfected with pCDNA3-UL9-MV were prepared as described in Materials and Methods, the 17B antibody detected an N-terminal fragment with an apparent mobility of approximately 38 kDa (Fig. 1B, lane 4). No specific bands were detected with the R250 antibody (data not shown).

Thus, we have demonstrated that in both insect and mammalian expression systems, no full-length UL9-MV protein is detectable; instead, an N-terminal fragment with similar if not identical mobility was observed in both cell types. Interestingly, a fragment with the same mobility was observed when UL9-MV was cloned with an N-terminal His tag and expressed in E. coli (Fig. 1B, lane 6). The apparent molecular mass of the N-terminal UL9-MV fragment was determined to be approximately 38 kDa, as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels with Benchmark (Invitrogen) or broad range (New England Biolab) molecular weight protein standards. Thus, it appears that a similar 38-kDa band is generated by expression of the motif V mutant in all three expression systems. We propose that the G354A mutation results in a conformational change(s) in the mutant protein leading to the exposure of a normally buried protease cleavage site(s). The difficulties that we encountered in detecting the 38-kDa fragment at first may indicate that some of the mutant MV protein is degraded completely. It is not clear whether the observed 38-kDa fragment is a result of cleavage by a protease present in all three cell types or whether this fragment represents the minimal stably folded fragment and is not the result of the initial cleavage event.

Potentiation is not due to absence of the transdominant origin-binding domain of UL9.

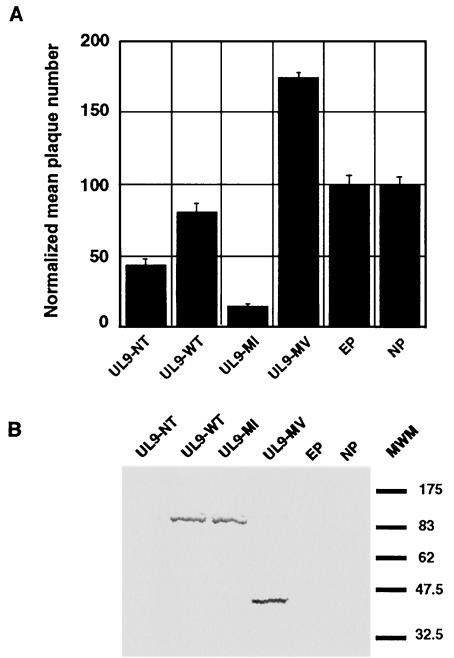

The UL9 C-terminal domain (UL9 CTD), encompassing residues 536 to 851, is transdominant in the context of the plaque reduction assay (2, 23) and in coinfections of wild-type HSV-1 and recombinant HSV-1 expressing the UL9 CTD (43, 44). The transdominant effect of the UL9 CTD is abolished if a mutation disrupting the origin-binding function is introduced (23, 39). Since the C terminus of UL9 is clearly transdominant and since no stable C-terminal fragments were detected when the potentiating mutant UL9-MV was expressed, we wanted to rule out the formal possibility that the absence of the C-terminal domain is responsible for potentiation. We hypothesized that the potentiating phenotype may simply be a result of the absence of the transdominant C-terminal portion of UL9. If this hypothesis is correct, it would be expected that the N-terminal portion of UL9 (UL9 NTD), lacking the transdominant origin-binding domain, would be potentiating.

In order to test this hypothesis, a construct expressing the UL9 NTD was generated and tested in the plaque reduction assay. Figure 2A shows that the UL9 NTD was transdominant rather than potentiating. Interestingly, the UL9 NTD protein was not detectable by Western blot analysis with the 17B antibody when used to transfect mammalian cells, even if concentrated cell lysates were prepared (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the UL9 NTD is unstable. This is consistent with previous observations from the baculovirus expression system (1, 30). It should be noted that when much larger amounts of plasmid DNA were used for transfection, the UL9 NTD could be detected but only at very low levels (see below). In summary, the transdominant phenotype of UL9 NTD rules out the possibility that potentiation is a result of the absence of the UL9 CTD.

FIG. 2.

UL9 N-terminal domain is transdominant. (A) The plaque reduction assay with pCDNA3-UL9-NT and control plasmids was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The UL9-MI-expressing plasmid is shown as a representative of a transdominant mutant, and the UL9-MV-expressing plasmid was used as a representative of a potentiating mutant. EP, empty plasmid; NP no plasmid. The error bars reflect the standard deviation calculated from at least three independent experiments. (B) The 17B antibody, recognizing the N-terminal 35 amino acids of UL9, was used to detect UL9 variants in concentrated lysates from cells transfected with the plasmids used in the plaque reduction assay, described for panel A. Broad Range prestained protein markers are depicted on the right.

Level of transdominance of UL9 NTD correlates with its stability and/or steady-state protein levels in the cell.

Since the UL9 NTD is unstable by itself while full-length UL9 is stable, we reasoned that the addition of a tag at the C terminus of the UL9 NTD might improve its stability. An AU1 tag was added at the C terminus of the UL9 NTD after residue 534, resulting in UL9 NTD-AU1. When mammalian cells were transfected with this construct, the tagged version of the N terminus (UL9 NTD-AU1) was readily detected in Western blots with the 17B antibody (Fig. 3B) as well as with the anti-AU1 antibody (data not shown). When UL9 NTD-AU1 was tested in the plaque reduction assay, it was found to be even more transdominant than the UL9 NTD (Fig. 3A). Transfection experiments with increasing amounts of plasmid DNA (Fig. 3C) demonstrated significant differences in the steady-state levels of UL9 NTD and UL9 NTD-AU1. Whereas UL9 NTD-AU1 was readily observed when 2 μg of plasmid DNA was used for transfection, UL9 NTD was hardly detectable when 7.5 μg of plasmid DNA was used (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Level of transdominance of UL9-NT depends on its stability and/or level of expression. (A) A plaque reduction assay with the indicated UL9 NTD variants was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The UL9-MV-expressing plasmid was used as a representative for a potentiating mutant. EP, empty plasmid; NP no plasmid. The error bars reflect the standard deviation calculated from at least three independent experiments. (B) The 17B antibody, recognizing the N-terminal 35 amino acids of UL9, was used to detect UL9 variants in concentrated lysates from cells transfected with the plasmids used in the plaque reduction assay, described forA. Broad Range prestained protein markers are depicted on the right. (C) Titration of the amount of plasmid DNA used for transfection is shown. The 17B antibody detected a protein species with an approximate molecular mass of 60 kDa, which correlates with the expected size of the UL9 NTD.

Although it is possible that the lower steady-state protein levels of UL9 NTD are due to lower expression levels, we consider it unlikely because both pUL9-NTD-AU1 and pUL9-UL9-NTD were expressed from the same promoter. We therefore favor a scenario in which the low steady-state levels of the UL9 NTD are due to inherent instability of the N-terminal fragment of UL9. Thus, the AU1 tag appears to increase the stability of the N-terminal domain of UL9. In summary, we have demonstrated that the potentiation phenotype of UL9-MV is not due to the absence of the C-terminal origin-binding domain of UL9. Furthermore, the UL9 NTD by itself is transdominant, and its level of transdominance correlates with stability and/or steady-state protein levels in the cell.

The potentiation phenotype of UL9-MV does not depend on the helicase activity of UL9.

In order to test whether the helicase activity of UL9 is essential for the potentiating phenotype of UL9-MV, a double mutant, UL9-MI/MV, carrying the K87A mutation in helicase motif I (Walker box A) was engineered. The K87A mutation abolishes the ATPase and helicase activities of UL9 (25). The UL9-MI mutant was previously shown to be transdominant in the context of the plaque reduction assay (23, 39). The double mutant UL9-MI/MV was found to be potentiating, resulting in approximately the same level of stimulation of viral plaque formation as UL9-MV by itself (data not shown). Thus, the addition of the MI mutation does not affect the potentiation phenotype of UL9-MV, indicating that potentiation does not rely on the helicase activity of UL9.

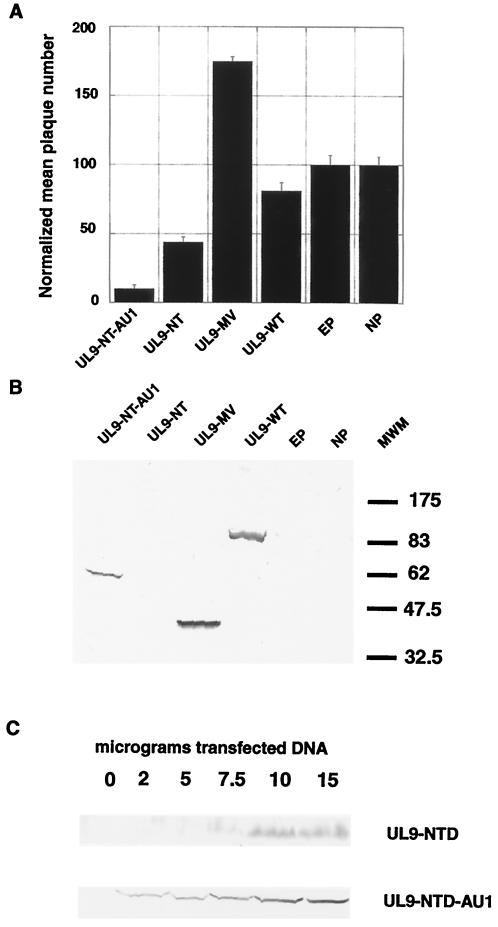

Presence of the MV (G354A) mutation by itself is not sufficient for potentiation.

As described above, UL9-MV potentiation is not simply a result of the absence of the transdominant CTD of UL9 and is independent of the helicase activity of the protein. Therefore, the potentiation is most likely a property of the G354A mutation itself. In order to investigate this hypothesis, several UL9 truncations were engineered (Fig. 4A): UL9-Δ322-851, which ends 22 amino acids upstream of the G354A mutation; UL9-Δ355-851-MV, which ends immediately after the MV mutation G354A and corresponds to a protein fragment with predicted molecular weight close to the experimentally determined size of the UL9-MV fragment observed in mammalian, insect, and bacterial cells (Fig. 4A and Fig. 1B); UL9-Δ450-851, which ends shortly after the last helicase motif of UL9 and contains wild-type sequence; and UL9-Δ450-851-MV, which ends shortly after the last helicase motif and contains the MV mutation (G354A).

FIG. 4.

Presence of motif V (G354A) mutation by itself is not sufficient to confer the potentiating phenotype. (A) Diagram of UL9 truncations. The N-terminal domain of UL9 is depicted as an open box. The C-terminal domain of UL9 is depicted as a gray box. The UL9 helicase motifs are depicted as black boxes. An asterisk points the position of the G354A mutation. The black line below the UL9 gene depicts the UL9-MV N-terminal fragment seen by Western blot analysis. (B) Plaque reduction assays with the indicated UL9 truncations were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The UL9-MV plasmid was used as a representative of a potentiating mutant. EP, empty plasmid; NP no plasmid. The error bars reflect the standard deviation calculated from at least three independent experiments. (C) The 17B antibody was used to detect UL9 truncations in concentrated lysates from Vero cells transfected with the plasmids used in the plaque reduction assay, described for panel A. Broad Range prestained protein markers are depicted on the right.

All the mutants except UL9-Δ450-851-MV were found to express proteins of the predicted sizes (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the UL9-Δ450-851-MV truncation produced a 38-kDa fragment comparable to the fragment seen with full-length UL9-MV (Fig. 4C). In the plaque reduction assay, all truncations except UL9-Δ450-851-MV were found to be transdominant (Fig. 4B). UL9-Δ450-851-MV was potentiating, and the level of potentiation was comparable to that seen with UL9-MV itself (Fig. 4B). From these experiments, it appears that there is a trend correlating the potentiation phenotype in the plaque reduction assay with the ability of UL9 variants to be processed or degraded to the 38-kDa N-terminal fragment. Our results show that the presence of the MV mutation by itself is not sufficient to confer potentiation, as seen from the transdominant phenotype of the UL9-Δ355-851-MV truncation. If the G354A mutation was sufficient for potentiation, then this truncation would be expected to be potentiating and not transdominant. It appears that, in addition to the G354A mutation itself, a region C-terminal to the G354A mutation (residues 354 to 450) is required for potentiation. Interestingly, neither the G354A mutation nor the region encompassing amino acids 355 to 450 was sufficient to confer potentiation when present alone. The G354A mutation may introduce a conformational change which leads to destabilization of the protein. The 355 to 450 region may be involved in protein-protein interactions within the UL9 dimer.

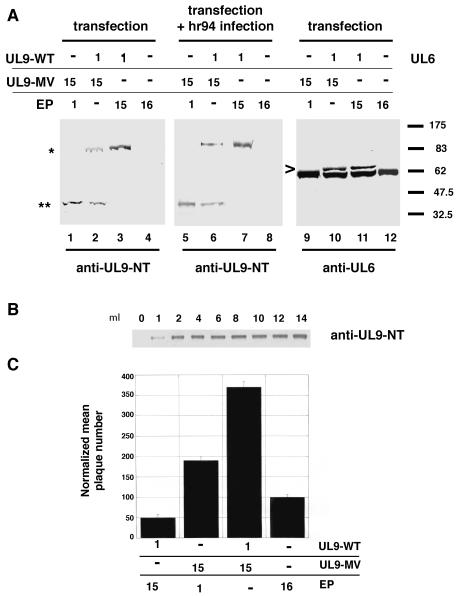

Overexpression of UL9-MV influences wild-type UL9 protein levels and is able to override the inhibitory effect of UL9.

Since the overexpression of wild-type UL9 is inhibitory for HSV-1 infection, the potentiation phenotype of UL9-MV may be a result of removal of UL9 during the course of infection, thereby preventing wild-type UL9 from exercising its inhibitory effect. In order to test this hypothesis, wild-type UL9 and UL9-MV were cotransfected in a ratio of 1:15, and the steady-state levels of full-length UL9 were followed by Western blot. Figure 5A shows that the overexpression of UL9-MV resulted in lower steady-state levels of wild-type UL9 (compare lanes 2 and 3). In order to determine whether destabilization would also occur in the context of infection, Vero cells were transfected with wild-type UL9 and UL9-MV (ratio, 1:15) and 24 h later were superinfected with the UL9 null virus hr94. In both experiments, shown in Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 4 (transfection), and Fig. 5A, lanes 5 to 8 (transfection and hr94 superinfection), the level of full-length UL9 was lowered approximately two- to threefold, as estimated from control Western blots in which various amounts of UL9 protein were analyzed for comparison (Fig. 5B). The possibility that the decrease in levels of full-length UL9 protein was due to transfection of large amounts of plasmid (a total of 16 μg per 60-mm2 plate) was ruled out by transfecting the cells with the same amount of empty plasmid in combination with wild-type UL9 (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 7).

FIG. 5.

Overexpression of UL9-MV affects the steady-state protein levels of UL9 and is able to override the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 in the plaque reduction assay. (A) Western blot analysis of lysates from cells transfected with pCDNA3-UL9-WT, pCDNA3-UL9-MV, or pCDNA3 empty plasmid (EP). The 17B anti-UL9 antibody was used for detection in lanes 1 to 8. The polyclonal anti-UL6 antibody was used for detection in lanes 9 to 12. The full-length UL9 is depicted with an asterisk (*). The UL9-MV fragment is depicted with two asterisks (**). UL6 is depicted with an arrowhead. A faster-migrating band cross-reacting with the anti-UL6 antibody is evident in lanes 9 to 12. Broad Range prestained molecular size markers are depicted on the right. (B) Titration of the UL9 amount in cell lysates with the 17B antibody. (C) A plaque reduction assay with the indicated plasmids was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The mean normalized plaque number and standard deviation were calculated from at least three independent experiments.

In order to determine whether the overexpression of UL9-MV resulted in the decrease in levels of an unrelated protein, the same experiment was performed but the levels UL6, an HSV-1 protein essential for cleavage and packaging, were monitored (Fig. 5A, lanes 9 to 12). The overexpression of UL9-MV did not lower UL6 steady-state protein levels. In summary, we found that overexpression of UL9-MV reproducibly lowered the levels of wild-type UL9 in the context of both transfection and infection.

To ask whether the decrease in steady-state levels of UL9 also correlated with the potentiation phenotype, the same experiment was performed in the context of the plaque reduction assay (Fig. 5C). In this case, Vero cells were cotransfected with wild-type HSV-1 infectious DNA and plasmids encoding wild-type UL9 and UL9-MV in a ratio of 1:10:150. As shown in Fig. 5C, wild-type UL9 had an inhibitory effect on plaque formation, but the overexpression of UL9-MV overrode the inhibition. Interestingly, cotransfection of wild-type UL9 and UL9-MV with wild-type HSV-1 infectious DNA resulted in even greater plaque numbers compared to the same experiment in which wild-type UL9 was omitted (Fig. 5C, compare the third and second bars). This further stimulation in the presence of wild-type UL9 may be due to differences in the timing of expression of UL9 from plasmids compared to expression from the viral genome. It may reflect the earlier activation of a degradation pathway which acts to lower the steady-state levels of UL9 (see below). In any case, these experiments indicate that the potentiation phenotype of the UL9-MV mutant is inversely related to the protein levels of wild-type UL9.

Indirect evidence that UL9 NTD and UL9-MV are able to interact with full-length UL9.

Our finding that UL9-MV lowers the steady-state protein levels of wild-type UL9 but not the steady-state levels of UL6 implies that UL9-MV may be capable of protein-protein interactions with wild-type UL9. In addition, it is possible that the UL9 NTD may exert its transdominant phenotype via heterodimerization with wild-type UL9. If this is correct, it would be expected that the UL9 NTD fragment would be able to form dimers. In order to test these hypotheses, UL9 NTD and UL9-MV proteins were expressed in insect cells with recombinant baculoviruses, partially purified, and subjected to gel filtration to evaluate their oligomerization state. This biochemical approach was unsuccessful due to problems with solubility and protein aggregation. We therefore took advantage of the knowledge of the position of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of UL9 (22) to demonstrate protein-protein interactions.

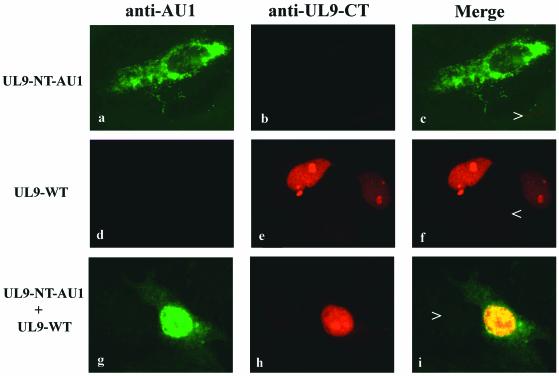

The UL9 NLS is localized within the last 107 residues of the protein (22). Thus, the UL9 NTD would be expected to be cytoplasmic when transfected alone. If the UL9 NTD is able to interact with full-length UL9, it would be expected to enter the nucleus when cotransfected with wild-type UL9. Our experiments show that when transfected alone, UL9 NTD-AU1 was cytoplasmic (Fig. 6, panels a, b, and c), but it was predominantly nuclear when cotransfected with wild-type UL9 (Fig. 6, panels g, h, and i). Furthermore, the UL9 NTD and wild-type UL9 staining colocalized in the nucleus (Fig. 6, panel i). In summary, since the UL9 NTD is able to enter the nucleus only when cotransfected with wild-type UL9 and not when transfected alone, we conclude that the UL9 NTD is able to heterodimerize with wild-type UL9 and utilize its NLS.

FIG. 6.

The N-terminal domain of UL9 is able to dimerize. Vero cells were transfected with UL9-NT-AU1 (panels a, b, and c), wild-type UL9 (panels d, e, and f), or both (panels g, h, and i) and stained with anti-AU1 and RH7 antibodies. Green (fluorescein) represents staining with anti-AU1 antibody. Red (Texas Red) represents staining with RH7 antibody. The arrowheads mark untransfected cells in the same field, which can be used as a reference for background staining. Panels c, f, and i are merged images of panels a and b, d and e, and g and h, respectively.

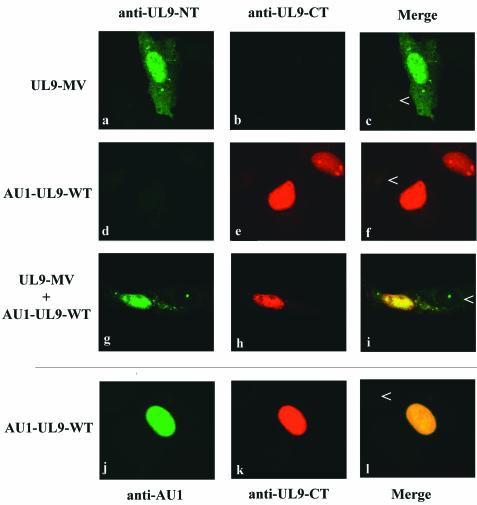

A similar experiment was performed for UL9-MV (Fig. 7). When cells were transfected with UL9-MV alone, nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was observed with the 17B antibody, which recognizes the N terminus of UL9 (Fig. 7, panel a). No staining was observed with the RH7 antibody, raised against the C-terminal domain of the protein (Fig. 7, panel b). When cells were cotransfected with UL9-MV and wild-type UL9, the majority of UL9-MV was seen in the nucleus, colocalizing with wild-type UL9 (Fig. 7, panels g, h, and i).

FIG. 7.

Cotransfection of UL9-MV with wild-type UL9 results in enhanced nuclear localization. Vero cells were transfected with UL9-MV (a, b, and c), AU1-wild-type UL9 (d, e, and f), or both (g, h, and i) and stained with 17B (anti-UL9-NT) and RH7 (anti-UL9-CT) antibodies. Green (fluorescein) represents staining with 17B antibody. Red (Texas Red) represents staining with RH7 antibody. The arrowheads mark untransfected cells in the same field, which can be used as a reference for background staining. Panels c, f, and i are merged images of panels a and b, d and e, and g and h, respectively. Panels j and k contain images of Vero cells transfected with AU1-WT-UL9 and stained with anti-AU1 and RH7 antibodies. Green (fluorescein) represents staining with anti-AU1 antibody. Red (Texas Red) represents staining with RH7 antibody.

In this experiment, we were able to distinguish between the UL9-MV protein and wild-type UL9 by taking advantage of the observation that the addition of the AU1 epitope to the N terminus of wild-type UL9 masked the N-terminal epitope recognized by monoclonal antibody 17B (Fig. 7, panel d). Thus, using a tagged version of wild-type UL9 allowed us to differentiate between the N terminus of UL9-MV, detected by the 17B antibody, and the N terminus of the AU1-tagged wild-type UL9, detected by the anti-AU1 antibody but not by 17B. Control double staining with anti-AU1 and RH7 antibodies showed that AU1-tagged wild-type UL9 was nuclear (Fig. 7, panels j and k) and that the staining patterns overlapped (Fig. 7, panel l). UL9-MV was both nuclear and cytoplasmic when transfected alone and predominantly nuclear when cotransfected with wild-type UL9. The fact that the localization of UL9-MV to the nucleus is improved in the presence of full-length wild-type UL9 is consistent with an interaction between them. The partial nuclear localization of the UL9-MV protein in the absence of wild-type UL9 may be due to the transient expression of full-length mutant protein which can enter the nucleus prior to being processed to the 38-kDa form. Alternatively, the UL9-MV N-terminal fragment may enter the nucleus by diffusion, but we consider this explanation unlikely due to its size.

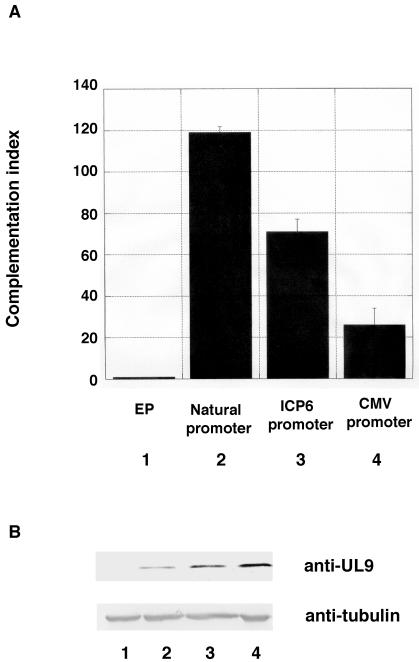

Inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 depends on level of UL9 protein.

Previous experiments have suggested that the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 is dose dependent (2, 23, 32), but a direct correlation between the actual protein levels of UL9 and the level of inhibition has not been demonstrated. The transfection of increasing amounts wild-type UL9 plasmid in the plaque reduction assay results in a proportional inhibition of HSV-1 infection (2, 23, 32), but in these experiments the UL9 protein levels have not been examined. In order to show a direct connection between the UL9 protein level and its inhibitory effect, the UL9 gene was placed under the control of three promoters with different strengths, and the ability of each construct to support the growth of hr94, a lacZ insertion UL9 mutant, was investigated in the transient transfection-complementation assay. The UL9 natural promoter is a weak promoter, and the ICP6 promoter is a relatively strong promoter which requires activation by ICP0 or VP16 in order to be transcribed. On the other hand, the cytomegalovirus promoter is a strong constitutive promoter. Figure 8 shows that there was an inverse correlation between the steady-state level of UL9 protein in the cell and the complementation index for wild-type UL9. The inhibitory effects of the wild-type UL9 protein are thus more pronounced when larger amounts of protein are present.

FIG. 8.

Inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 overexpression correlates with UL9 protein levels. (A) Transient transfection-complementation assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The bars indicate the mean complementation index. The error bars reflect the standard deviation calculated from three independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of lysates from cells transfected with the plasmids used in the complementation assay described in the legend to panel A. The R250 antibody was used to detect UL9, and polyclonal antitubulin antibody was used as a reference for sample loading. It has been estimated that lane 2 contains two- to threefold less UL9 than lane 3. On the other hand, lane 3 contains 1.5- to 2-fold less UL9 than lane 4.

DISCUSSION

UL9 is believed to play a key role in the initiation of viral DNA replication and the assembly of the viral replication machinery at the origin of replication, but many questions about its precise mode of action have not been answered. In this paper, we demonstrate that (i) inhibition of HSV-1 infection can be obtained by overexpression of full-length UL9, the C-terminal third of the protein containing the origin-binding domain, and the N-terminal two-thirds of UL9 containing the putative dimerization domain and the helicase motifs; (ii) the level of inhibition of HSV-1 infection by overexpression of wild-type UL9 correlates directly with the steady-state protein levels of the UL9 protein itself; and (iii) the MV mutant protein is unstable when expressed by transfection and is apparently processed to a 38-kDa N-terminal fragment or degraded completely. Potentiation correlates with the ability of the UL9 variants containing the G354A mutation to be processed or degraded to the 38-kDa form. Finally, overexpression of the MV mutant protein was able to influence the steady-state protein level of wild-type UL9 and to override the inhibitory effects of wild-type UL9. Based on the data presented here and in previous studies, we propose that the MV mutant protein is able to interact with full-length UL9 and that this interaction results in a decrease in the steady-state level of UL9, which in turn leads to enhanced viral infection.

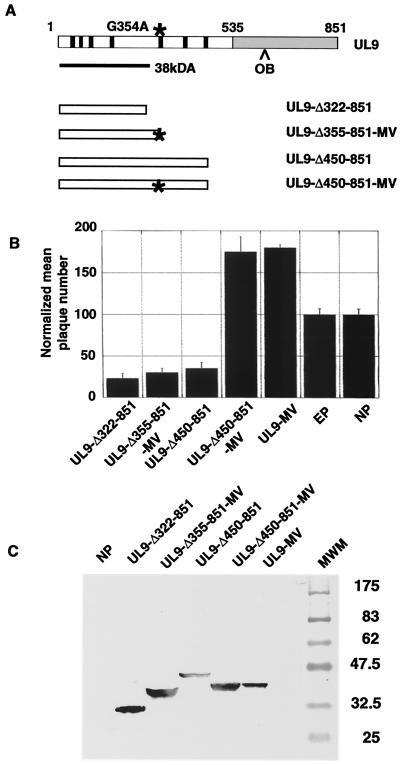

Model for transdominance and potentiation of UL9 helicase motif mutants.

The behavior of the UL9 helicase motif mutants in the plaque reduction assay (23) and their biochemical properties (24, 25) can be explained, at least in part, by a two-stage model for the progression of HSV DNA replication previously proposed by us and others (26, 35, 41). The two-stage model is depicted schematically in Fig. 9. The model posits that UL9 binds the origin of replication via its C-terminal domain (depicted with black circles). We propose that the binding of UL9 at an origin of replication results in origin unwinding and recruitment of the rest of the replication machinery. There is no direct evidence to indicate whether this initial UL9-dependent step occurs via a theta mechanism or by some other mechanism. Later in infection (stage II), we propose that replication proceeds in an UL9-independent manner to form the head-to-tail concatemers which are the observed products of viral DNA replication. Consistent with this model, studies with temperature-sensitive UL9 mutants indicate that UL9 is essential for the early stages of HSV-1 replication and appears to be dispensable for the later ones (6).

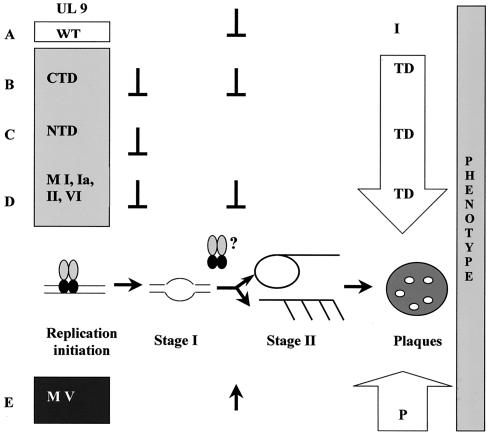

FIG. 9.

Model for the mechanism of potentiation-transdominance of the UL9 helicase motif mutants. The two-stage model for HSV-1 replication is depicted in the center of the figure. The behavior of wild-type UL9, the C- and N-terminal domains, and the transdominant motifs I, Ia, II, and VI is shown above the two-stage model. The cotransfection of these UL9 variants with wild-type infectious DNA results in decreased plaque number, as shown by the downward-facing arrow. Parentheses signify the proposed stage of inhibition of the viral infection. The behavior of the potentiating mutant MV is shown below the model with upward-facing arrows to show both the proposed stage of potentiation and the overall increase in plaque number. Abbreviations: I, inhibitory; TD, transdominant; P, potentiating. See text for details.

No direct evidence exists to answer the question of whether the later stages of replication occur via a recombination-driven and/or rolling-circle mechanism in infected cells. In insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses expressing the HSV replication proteins, origin-containing plasmids appeared to replicate by a rolling-circle mechanism, and this mode of replication was inhibited by the presence of UL9 (38). On the other hand, replicating DNA isolated from mammalian cells has a very complex structure, consistent with a recombination-mediated mechanism (reviewed in references 26 and 41). Whether stage II proceeds by rolling-circle or recombination-driven replication or both in HSV-infected cells, we propose that during the transition between stage I and stage II, UL9 is removed from the origin of replication so that it will not pose a physical barrier for the progressing replication fork. If an excess of UL9 is present, we predict that the origin clearance will be delayed or inhibited, resulting in lower overall viral titers (plaque numbers).

Figure 9A depicts a model in which overexpression of wild-type UL9 inhibits HSV-1 replication by inhibiting the progression from stage I to stage II. The inhibition appears to be mediated, at least in part, by the origin-binding function of UL9, since mutations which disrupt origin binding relieve the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 overexpression (23, 32, 39). Furthermore, the UL9 CTD is transdominant in the context of the plaque reduction assay (Fig. 9B). It is likely that the transdominance of the UL9 C-terminal domain is due to inhibitory effects at both stages of replication. The UL9 CTD is known to bind the origin of replication as efficiently as full-length UL9; therefore, this domain would be expected to compete for origin binding with wild-type UL9 originating from the HSV-1 infectious DNA. Expression levels of UL9 CTD exceeded that of the full-length wild-type UL9 in this experiment; therefore, UL9 CTD binding to the origin would be expected to result in a nonproductive complex at the origin due to the absence of the helicase domain, which is responsible for origin unwinding. Thus, HSV-1 replication will be inhibited at stage I.

Nevertheless, some of the HSV-1 genomes will be bound by wild-type UL9 originating from the cotransfected infectious DNA, and these will result in some stage I intermediates. Formation of stage II intermediates, however, will also be inhibited because of the inhibitory effects of UL9 remaining bound at the origin (Fig. 9A). The OBPC protein described by Baradaran et al. would also be expected to be inhibitory for HSV-1 infection because it contains the UL9 origin-binding domain (4, 5). In this paper, we report that the N terminus of UL9 can also exert a transdominant effect on HSV-1 infection (Fig. 9C). It is likely that the UL9 NTD inhibits HSV-1 replication at stage I by virtue of its ability to heterodimerize with full-length wild-type UL9. This is consistent with previous reports mapping the dimerization domain of UL9 to the N terminus (12, 13) and the results presented in Fig. 6. Although the N terminus would be expected to retain helicase activity (1, 30), the transdominant phenotype of the UL9 NTD indicates that the heterodimer of wild-type UL9 and UL9 NTD is probably not capable of unwinding the origin of replication. It is possible that the requirement for UL9 to bind the origin as a dimer is related to the ability of UL9 to bind to the origin of replication in a cooperative manner (11). In any case, it appears that the transdominance of the N-terminal domain of UL9 occurs by a different mechanism from that used by the C-terminal domain. The implications for mapping the dimerization domain of UL9 will be discussed below.

The transdominant helicase motif I (K87A), Ia (S110T, R112A, and R113A/F115A), II (E175A), and VI (R387K) mutants (23, 24) were found to be able to dimerize and bind oriS as efficiently as wild-type UL9 but did not exhibit helicase activity (25). Thus, as a result of the overexpression of mutant protein in the context of the plaque reduction assay, the majority of the UL9 present in the cell would be expected to consist of dimers of mutant proteins. Since the mutant homodimers bind the origin of replication as well as the wild type does, the majority of the origins of replication will be bound by helicase-negative mutant homodimers. Therefore, stage I is likely to be inhibited due to the absence of helicase activity (Fig. 9D). In addition, the progression from stage I to stage II replication would be inhibited by the mutant UL9 molecules remaining bound at the origin of replication by a mechanism similar to the inhibition by overexpression of wild-type UL9 described above (Fig. 9). Although we consider it unlikely, we cannot rule out the possibility that the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 and the transdominant effect of the helicase motif mutants and the UL9 NTD also involves the ability of these forms of UL9 to interact with other viral and/or cellular factors needed for HSV-1 replication. Further experiments will be necessary to determine whether these potential interactions contribute to the transdominance and inhibition.

The potentiating phenotype of the UL9-MV mutant is particularly intriguing. Potentiation is not simply a result of removing the origin-binding domain of UL9 and is independent of the helicase activity of UL9. In three different expression systems, a 38-kDa N-terminal fragment was observed, indicating that full-length mutant protein is unstable and processed to a smaller form; it is also likely that a portion of UL9 is degraded completely, given the difficulties we have experienced even detecting the 38-kDa fragment. It is possible that two degradation pathways exist, resulting in either complete degradation or the formation of the 38-kDa fragment, or that the 38-kDa fragment is a “semistable” intermediate of the complete degradation pathway. Although further investigation will be needed to distinguish between these possibilities, it is noteworthy that the levels of a cellular precursor of NF-κB appear to be controlled by two different proteolytic pathways: limited processing to a 50-kDa protein and complete degradation (17).

Despite the fact that no full-length UL9-MV protein was observed in any expression system tested, it is possible that full-length UL9-MV may be transiently expressed and be capable of protein-protein interactions with wild-type UL9. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the double mutant UL9-MV-OB, containing both the G354A and an origin-binding mutation, was more potentiating than the UL9-MV mutant alone (23). Since the OB mutation is an insertion after residue 591 in the C-terminal domain of UL9, in order this for mutation to have an effect, full-length protein must be synthesized at least transiently. Interestingly, we found that overexpression of UL9-MV lowered the wild-type UL9 protein level and overrode the inhibitory effect of wild-type UL9 in the plaque reduction assay. In addition, the partial ability of the motif V mutant protein to enter the nucleus (Fig. 7) suggests that the full-length version of this mutant protein may be transiently expressed, since the NLS is located at the very C terminus. These data, taken together, suggest that the MV mutant protein is transiently expressed as a full-length protein and is capable of interacting with wild-type UL9 and influencing both UL9 levels and the progression of the infection.

Based on the results presented in this paper, it is tempting to speculate that the expression levels of UL9 are regulated in the course of infection. It is possible that UL9 functions early in infection and that later in infection it is targeted for degradation. Thus, the regulation of steady-state levels of UL9 may play an important role in controlling viral infection. Posttranslational regulation of protein levels has been shown to play a major role in various cellular processes. Targeting specific proteins for degradation, often through an ubiquitin-mediated proteosomal pathway, is a commonly employed regulatory mechanism in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and other biological processes (33, 40). For instance, the specific degradation of the human cdc6 protein, a protein essential for DNA replication, was recently reported. During apoptosis induced by various stimuli, cdc6 is cleaved by caspase 3, preventing wounded cells from replicating (31).

Interestingly, UL9 has been shown to be phosphorylated during infection, although the sites of phosphorylation have not been identified and the biological significance of the phosphorylation has not been elucidated (16). Furthermore, the sequence analysis of UL9 revealed the presence of an internal PEST sequence at a position near the G354A mutation. PEST sequences are proline-, serine-, and threonine-rich motifs which have been shown to target proteins for ubiquitination and degradation, often in a phosphorylation-dependent fashion (19, 37). Taken together, these data suggest a possible mechanism for the regulation of UL9 through phosphorylation at or near the PEST sequence. It is possible that during infection, the steady-state levels of UL9 are controlled through a ubiquitin-mediated pathway. The G354A mutation may act to alter the conformation of the UL9 protein by exposing the PEST sequence and enhancing the degradation of itself and of wild-type UL9, with which it can interact. This scenario, although speculative, is consistent with the available data. Further studies will be necessary to determine whether the putative PEST sequence and phosphorylation play a role in the regulation of UL9 levels during infection.

Implications of UL9 transdominance for UL9 dimerization.

Since wild-type UL9 is a dimer in solution (13) and the UL9 CTD is a monomer (12), it has been assumed that the region responsible for dimerization is localized within the N-terminal domain of UL9 (residues 1 to 535). We attempted to map the dimerization region of UL9 by combining deletion analysis with biochemical methods, but our efforts were hampered by the protein insolubility of the tested deletions (data not shown). In this paper, we showed by immunofluorescent microscopy that the UL9 NTD transfected alone is cytoplasmic. In contrast, when cotransfected with wild-type UL9, it is imported into the nucleus. Presumably, the UL9 NTD heterodimerizes with wild-type UL9 and is imported into the nucleus by utilizing the NLS located at the C terminus of wild-type UL9. This result confirms the notion that the dimerization determinant(s) is localized in the N terminus of UL9. If our model that the transdominance phenotype of the UL9 NTD is mediated by dimerization is correct, then the plaque reduction assay might be used to map the region(s) of UL9 that is involved in dimerization. Our results show that the shortest N-terminal transdominant fragment is the UL9-Δ322-851 truncation, suggesting that at least one region involved in dimerization may lie within the first 322 amino acids of UL9. Further experiments will be needed to test this prediction.

In summary, in this paper, we have shown for the first time a direct correlation between the steady-state protein level of UL9 and the level of inhibition of HSV-1 infection. Transdominance appears to be mediated by overexpression, origin-binding activity, and dimerization. whereas potentiation is apparently caused by the ability of the potentiating UL9-MV mutant to influence the steady-state levels of wild-type UL9. Our results suggest that UL9 protein levels are an important factor in the progression of HSV-1 infection and perhaps subject to regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Weller laboratory for helpful discussions about the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge M. Challberg, D. Tenney, and W. Ruyechan for providing the antibodies used in this study. We thank A. Malik for the generation of the recombinant baculovirus expressing UL9-MV, P. Schaffer for providing plasmid pUL9Eco, and J. Nellissery for providing the pCDNA3-UL6 plasmid.

This investigation was supported by Public Health Service grant AI21747.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbotts, A. P., and N. D. Stow. 1995. The origin-binding domain of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL9 protein is not required for DNA helicase activity. J. Gen. Virol. 76:3125-3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbuckle, M. I., and N. D. Stow. 1993. A mutational analysis of the DNA-binding domain of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL9 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 74:1349-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Stuhl. 1990. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Baradaran, K., C. E. Dabrowski, and P. A. Schaffer. 1994. Transcriptional analysis of the region of the herpes simplex virus type 1 genome containing the UL8, UL9, and UL10 genes and identification of a novel delayed-early gene product, OBPC. J. Virol. 68:4251-4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baradaran, K., M. A. Hardwicke, C. E. Dabrowski, and P. A. Schaffer. 1996. Properties of the novel herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein, OBPC. J. Virol. 70:5673-5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumel, J., and B. Matz. 1995. Thermosensitive UL9 gene function is required for early stages of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 76:3119-3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmer, P. E., and I. R. Lehman. 1993. Physical interaction between the herpes simplex virus 1 origin-binding protein and single-stranded DNA-binding protein ICP8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8444-8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruckner, R. C., J. J. Crute, M. S. Dodson, and I. R. Lehman. 1991. The herpes simplex virus 1 origin-binding protein: a DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:2669-2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmichael, E. P., M. J. Kosovsky, and S. K. Weller. 1988. Isolation and characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 host range mutants defective in viral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 62:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Challberg, M. 1997. Herpesvirus DNA replication, p. 721-751. In P. Depamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eucaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 11.Elias, P., C. M. Gustafsson, and O. Hammarsten. 1990. The origin-binding protein of herpes simplex virus 1 binds cooperatively to the viral origin of replication oris. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17167-17173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias, P., C. M. Gustafsson, O. Hammarsten, and N. D. Stow. 1992. Structural elements required for the cooperative binding of the herpes simplex virus origin-binding protein to oriS reside in the N-terminal part of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17424-17429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fierer, D. S., and M. D. Challberg. 1992. Purification and characterization of UL9, the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein. J. Virol. 66:3986-3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorbalenya, A. E., E. V. Koonin, A. P. Donchenko, and V. M. Blinov. 1989. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4713-4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herskowitz, I. 1987. Functional inactivation of genes by dominant negative mutations. Nature 329:219-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isler, J. A., and P. A. Schaffer. 2001. Phosphorylation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein. J. Virol. 75:628-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karin, M., and Y. Ben-Neriah. 2000. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:621-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamberti, C., and S. K. Weller. 1998. The herpes simplex virus type 1 cleavage/packaging protein, UL32, is involved in efficient localization of capsids to replication compartments. J. Virol. 72:2463-2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang, V., J. Janzen, G. Z. Fischer, Y. Soneji, S. Beinke, A. Salmeron, H. Allen, R. T. Hay, Y. Ben-Neriah, and S. C. Ley. 2003. betaTrCP-mediated proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105 requires phosphorylation of p105 serines 927 and 932. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:402-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehman, I. R., and P. E. Boehmer. 1999. Replication of herpes simplex virus DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28059-28062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik, A. K., R. Martinez, L. Muncy, E. P. Carmichael, and S. K. Weller. 1992. Genetic analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL9 gene: isolation of a lacZ insertion mutant and expression in eukaryotic cells. Virology 190:702-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malik, A. K., L. Shao, J. D. Shanley, and S. K. Weller. 1996. Intracellular localization of the herpes simplex virus type-1 origin-binding protein UL9. Virology 224:300-389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Malik, A. K., and S. K. Weller. 1996. Use of transdominant mutants of the origin-binding protein (UL9) of herpes simplex virus type 1 to define functional domains. J. Virol. 70:7859-7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marintcheva, B., and S. K. Weller. 2003. Helicase motif Ia is involved in single-strand DNA-binding and helicase activities of the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein UL9. J. Virol. 77:2477-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marintcheva, B., and S. K. Weller. 2001. Residues within the conserved helicase motifs of UL9, the origin-binding protein of herpes simplex virus-1, are essential for helicase activity but not for dimerization or origin-binding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6605-6615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marintcheva, B., and S. K. Weller. 2001. A tale of two HSV-1 helicases: roles of phage and animal virus helicases in DNA replication and recombination. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 70:77-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez, R., L. Shao, and S. K. Weller. 1992. The conserved helicase motifs of the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein UL9 are important for function. J. Virol. 66:6735-6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLean, G. W., A. P. Abbotts, M. E. Parry, H. S. Marsden, and N. D. Stow. 1994. The herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein interacts specifically with the viral UL8 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2699-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monahan, S. J., L. A. Grinstead, W. Olivieri, and D. S. Parris. 1998. Interaction between the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding and DNA polymerase accessory proteins. Virology 241:122-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murata, L. B., and M. S. Dodson. 1999. The herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein. sequence-specific activation of adenosine triphosphatase activity by a double-stranded DNA containing box I. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37079-37086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelizon, C., F. D'Adda Di Fagagna, L. Farrace, and R. A. Laskey. 2002. Hum. replication protein Cdc6 is selectively cleaved by caspase 3 during apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 3:780-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry, H. C., D. J. Hazuda, and W. L. McClements. 1993. The DNA binding domain of herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein is a transdominant inhibitor of virus replication. Virology 193:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters, J. M. 2002. The anaphase-promoting complex: proteolysis in mitosis and beyond. Mol. Cell 9:931-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Severini, A., A. R. Morgan, D. R. Tovell, and D. L. Tyrrell. 1994. Study of the structure of replicative intermediates of HSV-1 DNA by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Virology 200:428-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Severini, A., D. G. Scraba, and D. L. Tyrrell. 1996. Branched structures in the intracellular DNA of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:3169-3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shelton, L. S., A. G. Albright, W. T. Ruyechan, and F. J. Jenkins. 1994. Retention of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) UL37 protein on single-stranded DNA columns requires the HSV-1 ICP8 protein. J. Virol. 68:521-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shumway, S. D., M. Maki, and S. Miyamoto. 1999. The PEST domain of IκBα is necessary and sufficient for in vitro degradation by mu-calpain. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30874-30881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skaliter, R., and I. R. Lehman. 1994. Rolling circle DNA replication in vitro by a complex of herpes simplex virus type 1-encoded enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10665-10669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stow, N. D., O. Hammarsten, M. I. Arbuckle, and P. Elias. 1993. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA replication by mutant forms of the origin-binding protein. Virology 196:413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulrich, H. D. 2002. Natural substrates of the proteasome and their recognition by the ubiquitin system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 268:137-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weller, S. 1995. Herpes simplex DNA replication and genome maturation, p. 189-213. In G. M. Cooper, R. G. Temin and B. Sugden (ed.), The DNA provirus: Howard Temin's scientific legacy. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 42.Weller, S. K., K. J. Lee, D. J. Sabourin, and P. A. Schaffer. 1983. Genetic analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants which define the gene for the major herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA-binding protein. J. Virol. 45:354-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao, F., and E. Eriksson. 1999. A novel anti-herpes simplex virus type 1-specific herpes simplex virus type 1 recombinant. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:1811-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao, F., and E. Eriksson. 1999. A novel tetracycline-inducible viral replication switch. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:419-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]