Abstract

Aims

To determine if iron binds strongly to captopril and reduces captopril absorption.

Methods

A variety of in vitro experiments was conducted to examine iron binding to captopril and a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over study design was used to assess the in vivo interaction. Captopril (25 mg) was coingested with either ferrous sulphate (300 mg) or placebo by seven healthy adult volunteers. Subjects were phlebotomized and had blood pressure measured at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h post ingestion. A 1 week washout period was used.

Results

The coingestion of ferrous sulphate and captopril was associated with a 37% (134 ng ml−1 h, 95% CI 41–228 ng ml−1 h, P=0.03) decrease in area under the curve (AUC) for unconjugated plasma captopril. There were no substantial changes in Cmax (mean difference;–32; 95% CI −124–62 ng ml−1(P=0.57)) or in tmax (mean difference; 0; 95% CI −18–18 min (P=0.65)) for unconjugated captopril when captopril was ingested with iron. There was a statistically insignificant increase in AUC for total plasma captopril of 43% (1312 ng ml−1 h, 95% CI −827–3451 ng ml−1 h P=0.27) when captopril was ingested with iron. The addition of ferric chloride to captopril resulted in the initial rapid formation of a soluble blue complex which rapidly disappeared to be replaced by a white precipitant. The white precipitate was identified as captopril disulphide dimer. There were no significant differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the treatment and placebo groups.

Conclusions

Co-administration of ferrous sulphate and iron results in decreased unconjugated captopril levels likely due to a chemical interaction between ferric ion and captopril in the gastrointestinal tract. Care is required when coprescribing captopril and iron salts.

Keywords: captopril, complex formation, drug interaction, heart failure, hypertension, iron

Introduction

Iron salts are used to treat iron deficiency anaemia, and are present in a number of multivitamin and mineral preparations [1]. Ferrous sulphate and other iron containing preparations decrease the absorption and clinical effectiveness of several commonly used drugs when coingested [2]. For example, iron has been shown to complex with and reduce the absorption of drugs such as tetracycline [3] and quinolone antimicrobials [4–6], l-dopa [7, 8], methyldopa [9], thyroxine [10], penicillamine [11], clondranate [12] and cefdinir a cephalosporin antimicrobial [13]. Captopril has been reported to react with iron and other transition metals [14–18]. However, the iron-captopril reaction has not been characterized under conditions mimicking those in vivo and the effect of iron on the pharmacokinetics of captopril has not been described. Given that captopril and iron containing preparations are commonly prescribed [19, 20], it is probable that a number of patients may be taking both of these medications concurrently. Therefore, we determined if ferrous sulphatewould alter the pharmacokinetics of captopril and further characterized the chemical interaction between captopril and iron.

Methods

This study was approved by the Conjoint Biomedical Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Calgary and informed consent was obtained from the study subjects. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over study design was used. Captopril (25 mg) was coingested with either 300 mg ferrous sulphate (inserted in a capsule) or identical appearing placebo (lactose) capsule by seven healthy volunteers (male/female: 5/2, mean age: 29.7 years, mean weight: 73.5 kg, mean height 1.78 m) after an overnight fast. None of the volunteers was using medications or nutritional supplements. Subjects were phlebotomized at baseline and 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 12 h postingestion. At baseline and after each blood drawing, blood pressure was measured using standardized patient preparation and measurement technique [21]. Subjects were not permitted to eat or drink until 3 h after ingestion of the study drugs. After a 1 week washout period, the subjects were crossed-over and the protocol was repeated.

Total and unconjugated plasma captopril levels were determined by the method of Pereira et al. [22]. Briefly, at each phlebotomy, 7 ml of whole blood were collected into EDTA containing blood collection tubes. The tubes were shaken and 1.3 ml of blood was immediately transferred into microcentrifuge tubes containing 0.065 ml of a solution of 0.1 m EDTA and 0.1 m ascorbic acid and vortexed. These tubes were centrifuged for 2 min, then 0.5 ml of the supernatant was transferred into two processing tubes each containing 2 ml of phosphate buffer (sodium phosphate dibasic/potassium phosphate solution adjusted to pH 7.0). A solution of 0.2 ml of NPM (1.5 mg N-(3-pyrenyl) maleimide ml−1 acetonitrile) was added to each processing tube and vortexed for 15 min. The time elapsed between taking a blood sample and the start of the last vortexing was kept under 5 min. Each sample was then frozen at −70 °C for determination of unconjugated captopril levels. The remaining blood (≈5 ml) in the EDTA vacuum tube was centrifuged at 2500 g for 15 min. Plasma was transferred into a processing tube and frozen at −70 °C for determination of total captopril level.

H.p.l.c. was used to determined unconjugated and total captopril concentrations by the method of Pereira et al. [22]. The time to maximal concentration (tmax ) and maximum concentration (Cmax ) were determined from the individual concentration-time data. AUCs were determined for both unconjugated and total captopril concentrations from baseline to the last measurable value using Lagrange interpolation [23]. A paired t-test and 95% confidence intervals were used to compare the tmax, Cmax, and AUC between the iron and placebo studies. Differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressures were compared using a paired t-test at individual postingestion times.

In order to characterize the chemical interaction of ferric and ferrous ions with captopril a number of experiments were carried out on a Shimadzu UV-260 double beam spectrometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc. Columbia, Maryland) with a 1 cm cell holder at 25 °C. The proton NMR spectra were run on a Bruker 300 MHZ NMR spectrometer (Bruker Spectrospin, Milton Ontario). Captopril disulphide dimer was a gift from Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd (Osaka, Japan).

Results

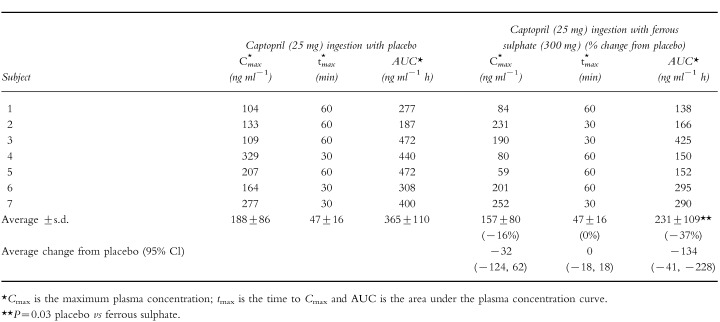

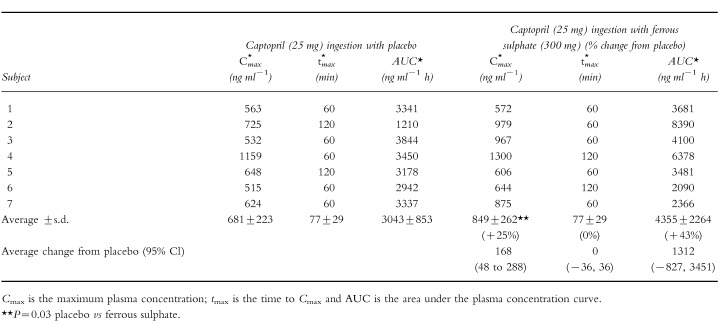

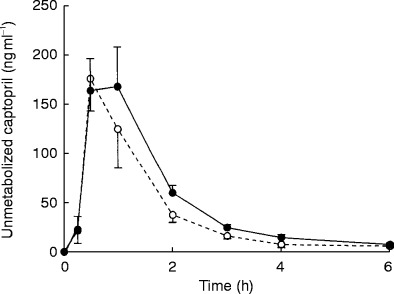

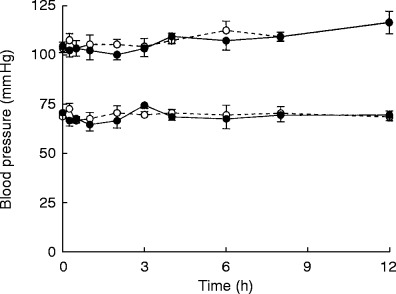

The effect of 300 mg ferrous sulphate on captopril AUC, Cmax or tmax can be seen in Tables 1 and 2]. Ferrous sulphate reduced unconjugated captopril AUC 37% (P=0.03, Table 1). There was an increase in total captopril Cmax of 25% (P=0.03) but the increase in total captopril AUC of 43%, was more variable and did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.27, Table 2). There was no substantial effect of ferrous sulphate on captopril tmax or on unconjugated captopril Cmax (Tables 1 and 2). The effect of iron on average plasma captopril levels can be seen in Figure 1. There was no significant difference in average systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the iron and placebo groups (Figure 2).

Table 1.

The effect of ingesting ferrous sulphate (300 mg) on unmetabolized captopril kinetic parameters.

|

Table 2.

The effect of ingesting ferrous sulphate (300 mg) on total captopril kinetic parameters.

|

Figure 1.

The effect of coingesting captopril (25 mg) with 300 mg ferrous sulphate (○) or placebo (•) on average (±s.e. mean of the intra individual differences) plasma captopril levels in seven healthy volunteers.

Figure 2.

The effect of coingesting captopril (25 mg) with 300 mg ferrous sulphate (○) or placebo (•) on average (±s.e. mean of the intra individual differences) systolic and diastolic blood pressure in seven healthy volunteers.

A reaction between ferrous ion (0.5 mm ) and captopril (0.5 mm ) was examined spectrophotometrically in air-saturated BIS-TRIS buffer (pH 6.0). The absorbance was observed to increase with time (t1/2≫12 min) in the 240–400 nm region. However, this absorbance increase occurred whether captopril was present or not, though at a slightly faster rate in its absence. These spectral changes were consistent with the aerobic oxidation of ferrous ion to ferric ion [7, 8]. These results indicate that ferrous ion does not directly interact with captopril. A similar conclusion was reached in a study of complex formation of captopril with several other dipositive metal ions [16].

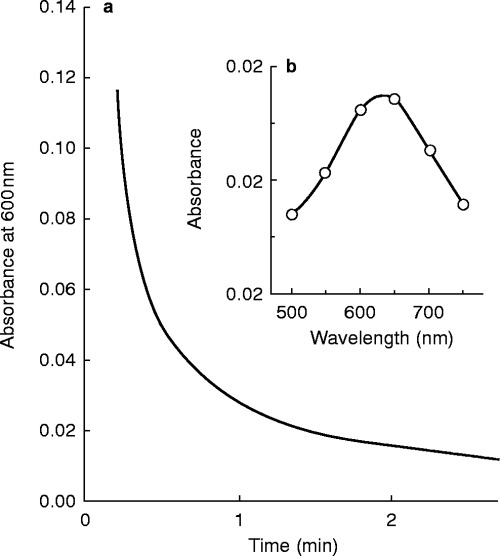

When ferric chloride (2 mm ) (or ferric nitrate) was mixed with captopril (2 mm ) a transient blue colour rapidly appeared in the solution. The blue colour lasted for a few seconds before fading away in about 1 min. After several minutes a white precipitate was observed to form. This reaction was observed to take place over the pH range 2–9. The change in absorbance corresponding to the loss of blue colour in the solution was followed with time at a wavelength of 600 nm (Figure 3). The maximum in the absorption spectrum of the blue complex was determined to be 630 nm (Figure 3). The presence of ferrous ion in the reaction mixture was confirmed by the production of a deep red colour upon adding bathophenanthroline disulphonate to the solution. The white precipitate was filtered from the reaction mixture and subjected to a number of tests in order to identify it. The precipitate did not contain any significant amount of iron as determined by the bathophenanthroline disulphonate test and, thus, is not an iron complex. The melting point (uncorrected) of the dried precipitate was 223–225 °C. This melting point compared with a melting point of 228–230 °C for authentic captopril disulphide dimer. In a final check on the identity of the precipitate, the proton-NMR spectra in deuterated DMSO of the white precipitate and captopril disulphide dimer were found to be identical. These results, taken together, strongly indicate that ferric ion rapidly and efficiently oxidizes captopril to produce the relatively insoluble captopril disulphide dimer and ferrous ion.

Figure 3.

a) Plot of absorbance at 600 nm vstime for the reaction of captopril (2 mm ) with ferric ion (2 mm ) at pH 2.7. There is a rapid initial unresolved increase in absorbance observed that results in the formation of a blue coloured complex. The decrease in absorbance shown (corresponding to the fading of the blue colour) occurs over several minutes. b) Shown in the inset is the absorption spectrum of the blue complex that was obtained by measuring the absorbance at different wavelengths at a fixed time of 12 s after ferric ion was mixed with captopril.

Discussion

Concurrent ingestion of ferrous sulphate and captopril reduces blood levels of unconjugated captopril. This drug interaction is likely to be clinically significant because both drugs are commonly prescribed and ferrous sulphate is also commonly purchased over-the-counter in multivitamin and mineral preparations [19, 20]. Unconjugated captopril is the active form of captopril therefore the interaction could result in loss of blood pressure control or in heart failure during concurrent therapy [27, 28].

Several other studies have reported on the reaction of ferric ion with captopril [17], glutathione and cysteine [24, 26]. For both glutathione and cysteine a transient blue complex was also observed upon mixing with ferric ion [24, 26–28]. The captopril sulphydryl radical was identified using electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping after ferric ion was mixed with captopril [17]. In the case of glutathione, it was proposed [24] that an intramolecular electron transfer occurs within a ferric-glutathione complex to produce a ferrous-glutathione radical complex that ultimately breaks down to form glutathione disulphide and ferrous ion. A similar sequence of reactions likely occurs for the reaction of ferric ion with captopril. The overall reaction in the gastrointestinal tract would thus be: 2Fe3++2R–SH →2Fe2++R–S–S–R+2H+ where R–SH is captopril and R–S–S–R is captopril disulphide dimer. This would result in a reduction in unconjugated captopril and an increase in captopril disulphide available for absorption. The results of our chemical and kinetic experiments are consistent with this explanation.

Experiments in animals have raised the possibility that captopril bound by disulphide bonds and in particular captopril disulphide may be converted to unconjugated captopril in vivo creating a ‘reservoir’ of active captopril [28–30]. In this study there was an increase in total captopril levels in blood raising the possibility that the iron–captopril interaction could prolong the duration of captopril in blood and not necessarily reduce overall captopril effectiveness. Clinical experience indicates this is unlikely to be a substantial factor in humans. Captopril bound by disulphide bonds is slowly cleared by humans and accumulates during therapy [28]. The increase in total captopril levels would be expected to result in prolongation of unconjugated captopril levels and duration of action if there was substantial conversion to unconjugated captopril. There is currently no evidence of an increase in duration of action or persistence of unconjugated captopril in blood during prolonged therapy in humans [27, 28] strongly arguing against substantial conversion of captopril bound by disulphide bonds to unconjugated captopril.

It is possible that the reduction in captopril blood levels seen in this study would not influence the effectiveness of captopril therapy. There was no effect of the interaction on blood pressure in this study. However, there was also no discernible hypotensive effect of captopril in these normotensive subjects. We calculated that ≫60 mild to moderately hypertensive patients would be required to demonstrate a 50% reduction in the hypotensive effect of captopril. A 35–60% reduction in captopril bioavailability associated with food and antacid [31–33] has been suggested not to influence the hypotensive effectiveness of captopril [31, 34, 35]. These later studies and our study did not have adequate power to exclude a substantial reduction in captopril effectiveness. The maintenance of captopril effectiveness in the presence of a substantial reduction in bioavailability does not have a biological rationale and is inconsistent with our current understanding of the dose response of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [28]. It is likely that a reduction in captopril levels of the magnitude seen in our study would have a similar effect to a 40% reduction in captopril dose.

Many patients require treatment with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and iron supplements. It may be possible to avoid the interaction by using an alternative angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor to captopril as the other angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors’ without the sulphydryl group are structurally less likely to bind metal ions as strongly as captopril [2]. Alternatively it may be possible to reduce the extent of the interaction by separating the time of ingestion of the two drugs by 2 or more hours [2].

In conclusion, care should be taken when prescribing iron preparations to avoid iron–drug interactions as iron binding drugs appears to be a common mechanism for drug–drug interactions [2].

References

- 1.Harju E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of iron preparations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;17:69–89. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198917020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell NR, Hasinoff BB. Iron supplements: a common cause of drug interactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuvonen PJ, Gothoni G, Hackman R, Bjorksten K. Interference of iron with the absorption of tetracyclines in man. Br Med J. 1970;4:532–534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5734.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polk RE, Healy DP, Sahai J, Drwal L, Racht E. Effect of ferrous sulfate and multivitamins with zinc on absorption of ciprofloxacin in normal volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1841–1844. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kara M, Hasinoff BB, McKay DW, Campbell NR. Clinical and chemical interactions between iron preparations and ciprofloxacin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:257–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell NR, Kara M, Hasinoff BB, Haddara WM, McKay DW. Norfloxacin interaction with antacids and minerals. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33:115–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell NR, Rankine D, Goodridge AE, Hasinoff BB, Kara M. Sinemet-ferrous sulphate interaction in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:599–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell NR, Hasinoff B. Ferrous sulfate reduces levodopa bioavailability: Chelation as a possible mechanism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:220–225. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell N, Paddock V, Sundaram R. Alteration of methyldopa absorption, metabolism, and blood pressure control caused by ferrous sulfate and ferrous gluconate. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;43:381–386. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell NR, Hasinoff BB, Stalts H, Rao B, Wong NC. Ferrous sulfate reduces thyroxine efficacy in patients with hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1010–1013. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osman MA, Patel RB, Schuna A, Sundstrom WR, Welling PG. Reduction in oral penicillamine absorption by food, antacid, and ferrous sulfate. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:465–470. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osterman T, Juhakoski A, Lauren L, Sellman R. Effect of iron on the absorption and distribution of clodronate after oral administration in rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;74:267–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueno K, Tanaka K, Tsujimura K, et al. Impairment of cefdinir absorption by iron ion. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:473–475. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jay D, Cuellar A, Jay EG, Garcia C, Gleason R, Munoz E. Study of a fenton type reaction: Effect of captopril and chelating reagents. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:740–746. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90474-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapenna D, De Gioia S, Mezzetti A, Ciofani G, Di Ilio C, Cuccurullo F. The prooxidant properties of captopril. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes MA, Smith GL, Williams DR. The binding of metal ions by captopril (SQ 14225). Part I. Complex of zinc (II), Cadmium (II) and Lead (II) Inorg Chim. 1985;107:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misik V, Mak IT, Stafford RE, Weglicki WB. Reactions of captopril and epicaptopril with transition metal ions and hydroxyl radicals: An EPR spectroscopy study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;15:611–619. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90164-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jay D, Cuella A, Jay E. Superoxide dismutase activity of the captopril-iron complex. Mol Cell Biochem. 1995;146:45–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00926880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonsen LL. Pharm Times. 1993:29–39. What are pharmacists dispensing most often? Top 200 drugs of 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.May FE, Stewart RB, Hale WE, Marks RG. Prescribed and nonprescribed drug use in an ambulatory elderly population. South Med J. 1982;75:522–528. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbott D, Campbell N, et al. Carruthers-Czyzewski P. Guidelines for measurement of blood pressure, follow-up, and lifestyle counselling. Can J Public Health. 1994;2 29s–43s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira CM, Tam YK, Collins-Nakai RL, Ng P. Simplified determination of captopril in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 1988;425:208–213. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(88)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ediss C, Tam YK. An interactive computer program for determining areas bounded by drug concentration curves using Lagrange interpolation. JPM. 1995;34:165–168. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(95)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamed MY, Silver J, Wilson MT. Studies of the reactions of ferric iron with glutathione and some related thiols. Inorg Chim. 1983;78:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng KL, Ueno K, Imamura T. CRC Handbook of organic analytical reagents. 1982. [Abstract]

- 26.Tanaka K, Kolthoff M, Stricks W. Iron-cysteinate complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:1996–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burnier M, Biollaz J. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;22:375–384. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199222050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duchin KL, McKinstry DN, Cohen AI, Migdalof BH. Pharmacokinetics of captopril in healthy subjects and in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:241–259. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drummer OH, Jarrott B. Captopril disulfide conjugates may act as prodrugs: disposition of the disulfide dimer of captopril in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:3567–3571. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummer OH, Kourtis S, Jarrott B. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme by metabolites of captopril. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1985:12–13. Suppl. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller HH, Overtack A, Heck I, Kolloch R, Sumpe KO. The influence of food intake on pharmacodynamics and plasma concentration of captopril. J Hypertension. 1985:135–6. S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singhvi SM, McKinstry DN, Shaw JM, Willard DA, Migdalof BH. Effect of food on the bioavailability of captopril in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;22:135–140. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1982.tb02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantyla R, Mannisto PT, Vuorela A, Sundberg S, Ottoila P. Impairment of captopril bioavailability by concomitant food and antacid intake. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1984;22:626–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salvetti A, Pedrinelli R, Magagna A, et al. Influence of food on acute and chronic effects of captopril in essential hypertensive patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7((Suppl 1)):29. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198507001-00006. S25–S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohman KP, Kagedal B, Larsson R, Karlberg BE. Pharmacokinetics of captopril and its effects on blood pressure during acute and chronic administration and in relation to food intake. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7((Suppl 1)):24. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198507001-00005. S20–S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]