Abstract

Aims

To describe age-and gender-related prescription patterns of diuretics in community-dwelling elderly, and to compare diuretics to other cardiovascular (CV) medications.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of patient-specific prescription data derived from a panel of 10 Dutch community pharmacies. Determination of proportional prescription rates and prescribed daily dose (PDD) of diuretics, cardiac glycosides, nitrates, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, β-adrenoceptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers in all 5326 patients aged 65 years or older dispensed CV medications between August 1st, 1995 and February 1st, 1996.

Results

Diuretics were prescribed to 2677 of 5326 patients (50.3%), 1325 patients (24.9%) using thiazides and 1198 patients (22.5%) using loop diuretics. Prescription rates of loop diuretics increased from 15.1% in patients aged 65–74 years to 37.2% in patients aged 85 years or older. Rates also increased for digoxin and nitrates. Rates for thiazide diuretics remained unchanged with age; rates for β-adrenoceptor blockers, ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers declined with age. Thiazides were prescribed to 30.1% of women compared with 16% of men (P<0.001). Average PDD was 135±117% of defined daily dose (DDD) for loop diuretics, and highest for bumetanide (245±2.01% of DDD, equivalent to 2.5±2.0 mg). Average PDD was 74±40% of DDD for thiazides, and highest for chlorthalidone (100±49% of DDD, equivalent to 25±12 mg).

Conclusions

Important characteristics of diuretic usage patterns in this elderly population were a steep increase in loop diuretic use in the oldest old, a large gender difference for thiazide use, and high prescribed doses for thiazides.

Keywords: diuretics, elderly, prescription patterns

Introduction

Cardiovascular (CV) diseases such as hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure, are prominent causes of chronic morbidity and mortality among the population aged 65 years and older [1, 2]. The high prevalence of these conditions leads to the use of large amounts of CV drugs. Diuretics are drugs of first choice in the treatment of hypertension and heart failure, and among the CV medications used most often by elderly patients. It is estimated that 25% to 40% of all persons, aged 65 years or older receive long-term diuretic therapy, and use of diuretics appears to be highest among the oldest old [3–5].

Diuretics are also a major cause of adverse drug effects in the elderly. Multiple pathology with absent or altered symptomatology, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes, and decreased homeostatic capacity complicate diuretic therapy in the elderly and it has been estimated that 60% of all serious adverse drug reactions in elderly patients are due to diuretics [6]. Diuretics are frequently involved in drug–drug interactions, an important cause of drug-related hospital admissions [7–10]. Ten percent of patients taking chronic diuretic agents will suffer from adverse effects requiring hospital admission [11], and particularly very old and frail patients appear at risk.

It is therefore of utmost importance to consider whether the frequent and long-term use of diuretics in old people is fully justified. Several studies have reported opportunities for diuretic withdrawal in elderly patient populations, suggesting overutilization or prescription of diuretics for too long periods [12–15]. Other investigators reported diuretic prescription in doses higher than defined daily dose-or national guideline-recommendations [16, 17]. However, detailed information on diuretic prescribing and dosing in community-dwelling elderly and very old patients is scant. The objective of the present study was to describe age-and gender-related variations in prescription rates and prescribed daily doses of diuretics in a large group of Dutch community-dwelling elderly and very old patients using CV medications. We also compared diuretic utilization patterns to five other CV medication classes.

Methods

We constructed a drug prescription database using computerized information (Pharmacom®, PharmaPartners, Oosterhout, The Netherlands) derived from a representative panel of 10 community pharmacies, located throughout The Netherlands in both rural and urban areas. Dutch pharmacies serve a generally well defined region of 10 000 persons, without commercial competition between pharmacies. Partly because of insurance regulations, such as direct payment of pharmacy bills by connected insurance companies, Dutch health care patients usually register with one pharmacy only. This allows for reconstruction of individual prescription drug use. Our database encompassed information on reimbursement and nonreimbursement medications dispensed to patients aged 65 years or older, including both privately insured patients and patients insured under the Dutch Compulsory Health Insurance Act. Prescription data of hospitalized patients and nursing home residents were not included. In the Netherlands, duration of medication prescriptions is limited to a period of 3 months, after which renewal of prescriptions is necessary. Therefore, to ensure a maximum inclusion of patients using CV medications, every prescription dispensed during a 6 month period (August 1st, 1995 to February 1st, 1996) was included in our database. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of the University Hospital Nijmegen.

The pharmacy files contained records of the medications dispensed, including date of dispensing, amount dispensed, and prescribed daily dose. They also included date of birth and gender of the patients receiving these medications, and all records included a unique patient identifier, which prevented duplicate registration of patients. Other personal identifiers, such as name and address, were removed from the files by the participating pharmacists. The drug codes were reclassified via a mapping program (AFTO 1.0©, Pharmacy Centre, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) classification system [18]. For the purpose of this study, diuretic medications were grouped together into thiazide diuretics (C03A and C03B), combination preparations of thiazides with potassium retaining diuretics (C03E), loop diuretics (C03C), and potassium retaining diuretics (C03D). A comparison was made with five other CV medication classes: cardiac glycosides (C01A), nitrates (C01D), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (C02E), β-adrenoceptor blockers (C07), and calcium channel blockers (C08). To compare age-and gender-related variations in prescription between diuretics and other CV medication classes, we computed proportional prescription rates. These rates are expressed as percentage use, and refer to all patients receiving at least one of the CV prescriptions of interest during the study period.

The mapping program further added generic name, formulation and strength of the preparation to all records, and computed the number of Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) dispensed. The DDD of a substance is established by the Nordic Council on Medicines and the WHO Drug Utilization Research Group and represents the recommended average daily dose of a drug, if used for its main indication in an average adult [18]. The legend duration of each prescription was computed by dividing the amount of drug dispensed by the prescribed daily dose. Prescribed daily doses could not be computed for nitrates and fixed hydrochlorothiazide/amiloride combination preparations. For all other prescriptions, the number of DDDs received per day was calculated by dividing the number of DDDs dispensed by the legend duration of the prescription. We excluded patients using more than 50 (n=2) or 0 DDDs per day (n=19), assuming data entry errors. Data on prescribed daily doses are presented as percentage of DDD plus or minus one standard deviation.

Forward conditional logistic regression was used to identify independent relations of age and gender with proportional prescription rates. Linear regression analysis was used to study the relation of mean number of CV medication classes in use and average prescribed daily doses with age and gender. In all analyses, regional differences (i.e. pharmacies) were taken into account. Analysis was carried out using the SPSS for Windows 6.1 package (SPSS Inc., 1994).

Results

During the 6 month study period, 164 902 prescriptions were dispensed to 11 387 patients. Of this population, one patient was excluded from further analysis because of an unknown date of birth. In total, 28 089 prescriptions for CV medications were dispensed to 5326 patients, encompassing 9187 diuretic prescriptions to 2677 patients (50.3%). Frusemide was prescribed most often in 1113 of 5326 patients (20.9%). Of patients using thiazides, 62.4% were prescribed fixed combination preparations with potassium sparing diuretics. Average prescribed daily doses were highest for bumetanide as a loop diuretic (245±2% of DDD) and chlorothalidone as a thiazide (100±49% of DDD). Potassium retaining diuretics or potassium supplements were used by 63.2% of patients using thiazide diuretics and by 18.4% of patients using loop diuretics.

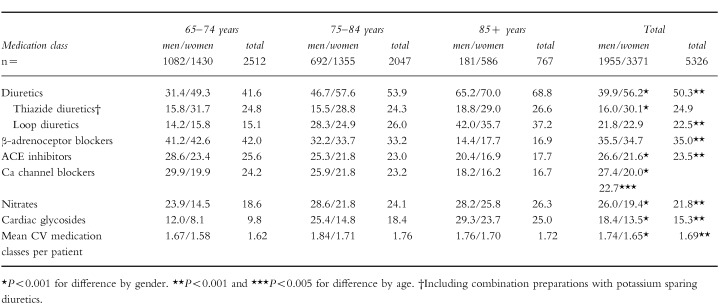

Table 1 compares proportional prescription rates for thiazide and loop diuretics with five other CV medication classes by age and gender categories. Prescription rates of loop diuretics increased with age from 15.1% to 37.2% in the oldest patients (P<0.001). Prescription rates for thiazide diuretics were not related to age. Declining prescription rates were found for β-adrenoceptor blockers (from 42.0% to 16.9%), ACE inhibitors (from 25.6% to 17.7%), and calcium channel blockers (from 24.2% to 16.7%). Rates for digoxin and nitrates increased with age, respectively, from 9.8% to 25.0% and from 18.6% to 26.3% (P<0.001). The mean number of different CV medication classes per person increased with age from 1.62±0.84–1.72±0.92 (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Proportional prescription prevalences of diuretics and five other cardiovascular (CV) medication classes by age and gender.

|

Prescription rates for thiazide diuretics were significantly higher for women (30.1%) than for men (16.0%) (P<0.001). Cardiac glycosides (18.4%vs 13.5%), nitrates (26.0%vs 19.4%), and ACE-inhibitors (26.6%vs 21.6%) were all prescribed more often in men (P<0.001). There were no gender related differences in prescription rates for loop diuretics or β-adrenoceptor blockers. In total, men were receiving more different medication classes per person compared with women (1.74±0.90 vs 1.65±0.88, P<0.001).

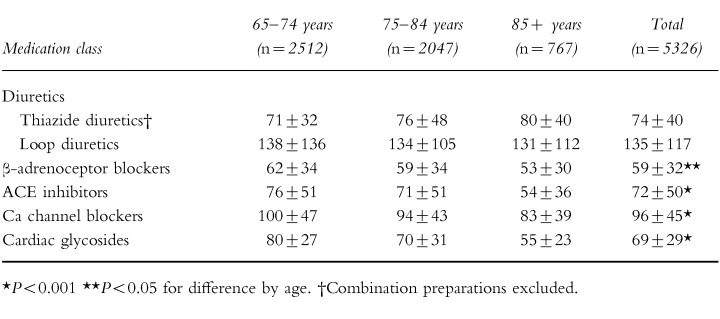

The average prescribed daily doses of diuretics are compared with four other CV medication classes for age-categories in Table 2. The average prescribed daily doses were above the DDD for loop diuretics, 53.7% of users receiving 1 DDD per day (equivalent to 40 mg frusemide) and 29.9% of users receiving more than 1 DDD per day. Average prescribed daily doses for thiazides were 74±40% of DDD (1 DDD is equivalent to 50 mg hydrochlorothiazide or 25 mg chlorothalidone). For all other CV medication classes, average prescribed daily doses were ≤1 DDD/day in all age-groups. (1 DDD is equivalent to, respectively, 0.25 mg digoxin, 50 mg captopril, 100 mg atenolol and 240 mg verapamil). The prescribed daily dose decreased with advancing age for all medication groups, except for diuretics. Loop diuretics were prescribed in higher doses to men (148±145% of DDD) compared with women (127±98% of DDD) (P<0.001). There were no gender differences in dosing of thiazides (71±32% of DDD in men vs 75±42% of DDD in women).

Table 2.

Prescribed daily dose as percentage of defined daily dose of cardiovascular medication classes by age.

|

Discussion

In this large population of Dutch community-dwelling elderly patients over 65 years, diuretics were the most frequently prescribed CV medication group (50% of patients). Proportional prescription rates for diuretics increased with advancing age from 42% to 69%. This was exclusively caused by a steep age-related increase in prescription rates for loop diuretics from 15% to 37%. Loop diuretics are pivotal in the treatment of congestive heart failure, and the prevalence of this disorder increases exponentially with age [19]. Indeed, heart failure patients frequently use loop diuretics in the long term [20]. However, chronic diuretic therapy has no place in the management of heart failure if congestion is absent [21], and may have adverse effects in diastolic heart failure [22], which is particularly prevalent in the oldest old. In addition, loop diuretics are frequently prescribed for ankle oedema without heart failure [16, 23]. Therefore, we think our data warrant further study of loop diuretic use in very old patients. In contrast with loop diuretics, the use of ACE inhibitors declined with advancing age. Explanations might be the relative novelty of the latter medications and the guidelines from the Dutch College of General Practitioners, stating monotherapy with loop diuretics as first choice in the treatment of elderly patients with congestive heart failure [24].

There were small gender related differences in prescription rates for most CV medication classes, probably due to gender-related variations in prevalences of CV and comorbid disorders or gender-related physician preferences. In contrast, however, thiazides were prescribed almost twice as often in women compared with men. This finding has been previously reported [17, 25], but without clear explanation. Guidelines for choosing antihypertensive medication in the elderly do not differ between men and women [26]. The more frequent occurrence of side-effects of thiazides in men or a higher prevalence of postural ankle oedema in women appear less plausible explanations for the large gender difference.

Daily prescribed doses decreased for most CV medication classes to 50% of the DDD in the oldest old, as might be expected on the basis of an age-related decline in renal and hepatic clearance. Loop diuretics were prescribed in doses above the DDD and doses did not decline with age. Both decreasing renal function and increasing severity of heart failure with age may necessitate the prescription of higher doses of loop diuretics. Men received higher average daily doses of loop diuretics than did women. This may reflect higher heart failure mortality rates [19] and higher hospital discharge rates for heart failure in men [27]. Average prescribed daily dose of thiazides (equivalent to 37 mg hydrochlorothiazide) was well above the recommended daily dose for hypertension in the elderly (12.5 mg). Excessive thiazide dosing should be avoided, since most adverse effects are dose-dependent [28]. Thiazides may have been prescribed in higher doses for heart failure or ankle oedema.

Several limitations need to be considered. Since data on age and gender of patients not using any medications were unavailable, we reported proportional variations in prescription rates and not on prevalence rates. However, this does allow description of diuretic utilization patterns and a comparison with other medication classes. Ideally, possible inconsistencies in diuretic prescription patterns, such as were found in this study, should be verified by comparison with clinical data of the patients concerned. Because of privacy regulations, we were unable to obtain this information. In addition, there may be discrepancies between the number of medications dispensed by pharmacies and the numbers prescribed by physicians. This difference is estimated at 3% for CV drugs and such a figure would not substantially influence our results [29]. Furthermore, good concordance between dispensory data and patient interviews for CV medications has been etablished [30].

The present study expands current knowledge on diuretic prescription patterns by age and gender in elderly patients. Utilization patterns and prescribed daily doses of thiazide and loop diuretics in elderly patients differ distinctly from those for other CV medication classes. These changes may be explained in part by changes in morbidity and pharmacokinetics. However, possible inconsistencies in diuretic prescription patterns cannot be excluded. We found a steep increase in loop diuretic use in the oldest old, a large gender difference for thiazide prescription rates, and relatively high daily prescribed doses for thiazide diuretics. High numbers of adverse events in older patients are attributed to diuretics, and an extended assessment of diuretic utilization in the elderly in future studies should include these issues.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Netherlands Program for Research on Ageing, NESTOR, funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sciences, and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. The authors wish to thank Henk J. J. van Lier, MSc, Department of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands, for his help with the statistical analyses. Special appreciation is extended to Jerry H. Gurwitz, MD, The Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, Massachusetts, for his helpful comments on this manuscript, to Edmund Sadyo, MD, and to the participating pharmacists from the Health Base Foundation, Houten, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Dewhurst G, Wood DA, Walker F, et al. A population survey of cardiovascular disease in elderly people: Design, methods and prevalence results. Age Ageing. 1991;20:353–360. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittelmark MB, Psaty BM, Rautaharju PM, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular diseases among older adults. The cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:311–317. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumble RH, Morgan K. Longitudinal trends in prescribing for elderly patients: two surveys four years apart. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:571–575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jörgensen TM, Isacson DGL, Thorslund M. Prescription drug use among ambulatory elderly in a Swedish municipality. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:1120–1125. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrischilles EA, Foley DJ, Wallace RB, et al. Use of medications by persons 65 and over: data from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47:144. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.m137. m137–m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson J, Chopin JM. Adverse reactions to prescribed drugs in the elderly: A multicentre investigation. Age Ageing. 1980;9:73–80. doi: 10.1093/ageing/9.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson KM, Talbert RL. Drug-related hospital admissions. Pharmacother. 1996;16:701–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jankel CA, Fitterman LK. Epidemiology of drug–drug interactions as a cause of hospital admissions. Drug Safety. 1993;9:51–59. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199309010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doucet J, Chassagne P, Trivalle C, et al. Drug–drug interactions related to hospital admissions in older adults: A prospective study of 1000 patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:944–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper JW. Probable adverse drug reactions in a rural geriatric nursing home population: a four-year study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:194–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lye MDW. Chronic cardiac failure in the elderly. In: Brocklehurst JC, Tallis RC, Fillit HM, editors. Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraaij van DJW, Jansen RWMM, Bruijns E, Gribnau FWJ, Hoefnagels WHL. Diuretic usage and withdrawal patterns in a Dutch geriatric patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:918–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straand J, Fugelli P, Laake K. Withdrawing long-term diuretic treatment among elderly patients in general practice. Fam Pract. 1993;10:38–42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonge de JW, Knottnerus JA, Zutphen van WM, Bruijne de GA, Struijker Boudier HAJ. Short term effect of withdrawal of diuretic drugs prescribed for ankle oedema. Br Med J. 1994;308:511–513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6927.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walma EP, Hoes AW, Dooren van AW, Prins A, Van Der Does E. Withdrawal of long term diuretic medication in elderly patients: a double blind randomised trial. Br Med J. 1997;315:464–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7106.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straand J, Rokstad K. Are prescribing patterns of diuretics in general practice good enough? Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15:10–15. doi: 10.3109/02813439709043422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wills P, Fastbom J, Claesson CB, Cornelius C, Thorslund M, Winblad B. Use of cardiovascular drugs in an older Swedish population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) classification index including defined daily doses (DDDs) for plain substances. Oslo: WHO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannel WB, Belanger BJ. Epidemiology of heart failure. Am Heart J. 1991;121:951–957. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young JB, Weiner DH, Yusuf S, et al. Patterns of medication use in patients with heart failure: A report from the Registry of Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) South Med J. 1995;88:514–523. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohn JN. The management of chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:490–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei JY. Age and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1735–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212103272408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke KW, Gray D, Hampton JR. How common in heart failure? Evidence from PACT (Prescribing Analysis and Cost) data in Nottingham. J Public Health Med. 1995;17:459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walma EP, Bakx HCA, Besselink RAM, et al. NHG standaard hartfalen. Huisarts Wet. 1995;38:471–487. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espeland MA, Kumanyika S, Kostis JB, et al. Antihypertensive medication use among recruits for the trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE) J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1183–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report on hypertension in the elderly. Hypertension. 1994;23:275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonneux L, Looman CWN, Barendregt JJ, Van Der Maas, PJ PJ. Regression analysis of recent changes in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Netherlands. Br Med J. 1997;314:789–792. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacConnachie AM, Maclean D. Low dose combination antihypertensive therapy—additional efficacy without additional adverse effects? Drug Safety. 1995;12:85–90. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199512020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beardon PHG, McGilchrist MM, McKendrick AD, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM. Primary non-compliance with prescribed medication in primary care. Br Med J. 1993;307:846–848. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6908.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RE, Vollmer WM. Comparing sources of drug data about the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:1079–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]