Abstract

Married women in rural Papua New Guinea are at risk for HIV primarily because of their husbands’ extramarital relationships. Labor migration puts these men in social contexts that encourage infidelity. Moreover, many men do not view sexual fidelity as necessary for achieving a happy marriage, but they view drinking and “looking for women” as important for male friendships.

Although fear of HIV infection is increasing, the concern that men most often articulated about the consequences of extramarital infidelity was possible violent retaliation for “stealing” another man’s wife. Therefore, divorced or separated women who exchange sex for money are considered to be “safe” partners. Interventions that promote fidelity will fail in the absence of a social and economic infrastructure that supports fidelity.

Epidemiological and ethnographic research in a wide range of societies has found that married women are at risk for HIV primarily because of their husbands’ extramarital sexual liaisons, and wives have little control over this risk, which is not lessened by their own fidelity.1 Such findings indicate that to understand the dynamics of marital HIV transmission, it is necessary to delineate the economic, social, and cultural factors that propel and structure men’s extramarital sexuality. Although it is probably present to some extent in all societies, men’s extramarital sexuality varies widely in terms of frequency, pattern, cultural meaning, and personal significance. Socioeconomic contexts structure both opportunities and disincentives for men’s extramarital liaisons; thus, whether and how often a married man engages in extramarital sexual relations depend on a wide range of material and ideological factors, including geographical opportunity, the degree of stigma or prestige conferred by extramarital liaisons, male peer group patterns of socializing, and so on. Accordingly, I analyzed the economic and cultural contexts that shape the behavioral patterns and social meanings of men’s extramarital sexuality in rural Papua New Guinea.

An important yet rarely acknowledged factor that potentially influences men’s extramarital sexuality is the social construction of marriage, i.e., the emotional, cultural, and economic meanings of conjugality in a society. The ethnographic record shows that husbands’ and wives’ economic and emotional roles and expectations of each other vary culturally and are influenced by other factors, such as a society’s economic organization, political organization, religion, and gender relations and a couple’s socioeconomic status.2 However, “ABC” approaches to HIV/AIDS prevention (promoting sexual Abstinence before marriage, Being faithful within marriage, and using Condoms with sexual partners when the first 2 behaviors are not possible3) are premised on a unitary and highly idealized Western construction of the marital relationship. The social science literature often refers to this as companionate marriage, where marriage is expected to be a person’s primary source of emotional gratification and marital sexual fidelity is a key symbol of this intense emotional bond. Thus, engaging in extramarital sexual relations forsakes or violates this bond.4 The literature on ABC approaches to HIV/AIDS prevention rarely acknowledges that the marital relationship may not be universally conceptualized as companionate in accordance with an idealized Western model or that there may be competing economic and ideological pressures on men that minimize the value and practicability of marital fidelity.5

My case study of the Huli in Papua New Guinea shows the problems that are associated with uncritically advocating and expecting marital fidelity. Findings from the study included:

Huli men’s mobility and labor-related absences from home put them in social contexts in which extramarital sexuality is extremely likely.

Huli men view extramarital sexual relations more as a potential transgression against other men and less as a transgression against their wives or the marital bond.

Economic decline and men’s long-term absences from home have resulted in a growing number of Huli women who have sexual relations in exchange for money. These women are often described as “safe” extramarital partners because sexual relations with them are unlikely to result in retaliation from absent husbands.

Most Huli men do not see sexual fidelity as necessary for having a successful and happy marriage, and they assert that seeking out alternative sexual partners is appropriate at some junctures during the course of a marriage.

These findings indicate that there are more socioeconomic structures that promote, enable, and normalize Huli men’s extramarital sexuality—and thus increase women’s HIV risk—than constrain or discourage it. Furthermore, this research suggests that rather than conceptualize marital infidelity as a matter of individual choice over which men can and should exert control regardless of context, HIV/AIDS prevention policies and programs should specify and target the socioeconomic structures that make the choice of extramarital sex so likely.

RESEARCH SETTING

With a population of almost 6 million, Papua New Guinea occupies the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and some surrounding smaller islands. It gained independence from Australia in 1975, and although 1 of the official national languages is English, it is home to more than 850 indigenous languages. Steep mountains, dense tropical rain forest, and lack of infrastructure impede the delivery of government services and the development of the country’s wealth of mineral resources. Recent economic decline and deterioration in the quality of governance has resulted in worsening health indicators.6 The current estimate of HIV prevalence is 1.6% among those aged 15 to 49 years, with rates between 2% and 4% in urban areas, along major highways, and in the rural areas that surround resource development sites, such as gold mines.7 Gender inequality, high rates of untreated sexually transmitted infections, and high prevalence of sexual violence against women are significant factors in the spread of HIV in Papua New Guinea.8

This research was conducted in the small rural town of Tari, Southern Highlands Province, among the Huli, a cultural group of approximately 100 000 individuals. Most Huli are still primarily subsistence horticulturalists; however, cash is required for school fees, basic household goods, and some food staples. Because little wage or salaried labor is available in Tari, most people make money by selling coffee and other agricultural produce. Remittances from family members who work outside of Tari also are important. In 2004, when this study was conducted, the Papua New Guinea currency had undergone a precipitous decline and was worth one third of its value 10 years earlier.9 The costs of store-bought goods had increased accordingly, but wages and the prices that people could command for their agricultural products had not. Interviews and informal conversations showed that many people could no longer afford to pay for their children’s school fees or for food staples, such as canned mackerel, that had previously been a regular part of the local diet. Crime also had increased, and many salaried employees had fled the area, which led to the closure of some primary schools and health centers, the small bank, and the post office.10

Tari District Hospital began testing for HIV in 1996 and had documented 72 cases by mid-2004.11 The head nurse was familiar with all 72 cases, and her description of each case indicated that at least 19 of the 31 women who were HIV-positive or who had died of AIDS had been infected by husband-to-wife transmission.12

In the anthropological literature, the Huli are known for gender avoidance, i.e., for having a set of cultural beliefs and practices that minimizes contact between men and women.13 In the past, for example, husbands and wives lived in separate houses, worked in separate agricultural fields, and did not cook or eat together. Traditional Huli aphorisms warn that immoderate marital contact—particularly sexual contact—can result in sickness and worsening fortunes among men and premature aging among both men and women.14

Since the late 1960s, the influence of Christian missionaries has diminished the importance of traditional gender avoidance beliefs and practices. Most married couples now live together in 1 house, and churches play a powerful role in shaping day-to-day social activity by sponsoring sports games, youth groups, women’s groups, prayer groups, Bible study groups, and Huli literacy classes.15 Christian churches also have shaped local understanding about AIDS, which is described by many Huli as either divine punishment or a message from God that people must renounce their sinful ways and embrace Christianity. Likewise, many people object to condom promotion and describe condoms as a technology that enables people to evade God’s will that they either embrace moral sexual practice (marital sexual relations only) or be punished with disease for failure to do so.

METHODS

This study was conducted between February and August 2004. The data were obtained through participant observation, interviews with key informants (experts with local knowledge on particular aspects of marriage or men’s extramarital sexuality), collection of both popular media and official documents about HIV/AIDS and marriage, and interviews with 40 married Huli men and 25 married Huli women. The interview subjects were selected with the objective of achieving diversity in the sample along 3 axes: generation, socioeconomic status, and postmarital migration experience (Table 1 ▶).16 Interviews were tape recorded, transcribed, and then analyzed to identify overarching themes and to delineate whether and how these themes corresponded with the axes of participant diversity.

TABLE 1—

Overview of Ethnographic Methods: Case Study, Tari, Papua New Guinea, February-August 2004

| Method | Description of Method and Relationship to Project Objectives | Description of Sample |

| Participant observation | Six months of observational data on domestic life and social life to better understand the marriage experience, men and women’s patterns of socializing, and health worker–patient interactions. | The households of married couples; Tari market; Tari District Women’s Center; Tari District Hospital. |

| Semistructured interviews | Interviews with 40 married men conducted by 4 Huli male field assistants who were trained in interviewing skills and research ethics. Interview questions elicited information on courtship, premarital sexuality, marital sexuality, extramarital sexuality, ideals and expectations of marriage, household decisionmaking patterns, household division of labor, marital emotional life, patterns of spousal communication, and causes and outcomes of marital conflict. | 3 newly married men with no history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 2 newly married men with a history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 1 newly married man with a history of migration/mobility with high economic status. 5 middle-aged men with no history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 11 middle-aged men with a history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 4 middle-aged men with a history of migration/mobility with high economic status. 4 grandparents/men with adult children with no history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 7 grandparents/men with adult children with a history of migration/mobility with low economic status. 3 grandparents/men with adult children with a history of migration/mobility with high economic status. |

| Key Informant interviews | 5 interviews with people who had expert local knowledge on particular aspects of marriage and men’s extramarital sexuality. | 1 priest, 3 health professionals, 1 women’s center staff member. |

| Archival research | Collection of written and other media to identify cultural, religious, and demographic factors that shape individual behavior. | Popular media (primarily newspaper articles about HIV/AIDS, marriage, bride wealth, and the mining industry); educational videos about HIV/AIDS distributed by the Papua New Guinea National AIDS Council; reports based on demographic data collected for 25 years by the Tari Research Unit; religious instructional texts on marriage, sexuality, and the family. |

Note. Men who had been married less than 5 years were categorized as newly married; men who had been married 5 years or more but who did not yet have adult children were categorized as being middle aged; men who had grandchildren or adult children were categorized as being part of the grandparent generation. Postmarital migration and mobility was defined as having lived outside of Tari for at least 6 months after marriage or as having made overnight trips away from Tari at least a few times a month. A man was categorized as having high economic status if he had a waged or salaried job or made enough money selling coffee to live in a fiberboard house with a metal roof; men who did not have jobs and who lived in bush material houses were categorized as having low economic status.

Like the other researchers in this 5-country comparative study (the other countries are Mexico, Nigeria, Uganda, and Vietnam), I had intended to carry out marital case study interviews.17 This methodology specified that I, as a woman, interview the married women and that trained Huli male field assistants interview the husbands of these women. However, this particular methodology was not feasible at the Papua New Guinea project site. Specifically, men wanted to be interviewed first and, once interviewed, refused to allow their wives to be interviewed. Women that I interviewed were similarly unwilling to ask their husbands to participate in the study. Consequently, the research team interviewed men and women who were married but not to each other.18

In addition to the interview questions used at all 5 country field sites, Huli men were asked why they were reluctant to let their wives participate in the study. The most common assertion was that no self-respecting man would permit his wife to participate in a study that included questions about sexual relations and marriage because (1) talking about sexual relations automatically aroused a woman’s desire, which would consequently make a wife more likely to stray; and (2) a husband’s authority might be undermined, because wives were likely to use the interview setting as a venue for airing complaints and even deriding a husband. These concerns suggest that the idealized model of companionate marriage—with its presumptions of mutual trust—does not carry much emotional weight with Huli men and that male authority continues to be central to their models of marriage.

RESULTS

Men’s Extramarital Sexuality

Ethnographic research among the Huli from the 1970s and 1980s suggests that male infidelity was strongly discouraged and rarely practiced, in part because of pronounced fears of female sexual fluids, and in part because almost all adult women were married, and extramarital sexuality thus constituted the appropriation of another man’s wife.19 Moreover, newly married couples were taught that their own individual moral conduct could affect the other’s health and well-being.20 For example, a man’s infidelity was said to make his wife and young children sick and exhausted, even in the absence of physical contact with them. This lesson is still a part of marriage rituals, and it was the explanation offered by men in the newly married generation for why they did not engage in extramarital sexual relations. Furthermore, men learn in church and through Christian youth groups that extramarital sexual relations are a sin in the eyes of God. Finally, an important marker of adult masculinity is getting married and having children, and maintaining a smoothly functioning household is important to this vision of competent adult masculinity. Men whose wives make public scenes about their husbands’ philandering are seen as less capable. To summarize, there are many factors that would seem to motivate men to refrain from extramarital sexuality.

Nevertheless, almost all of the men who were interviewed had engaged in extramarital sexual relations at some point, and many had done so within the past month.21 Men described most of their liaisons as brief encounters in which the women were paid. However, they did distinguish between the nature of the liaisons they had when away from Tari and those that occurred in Tari. Liaisons away from Tari typically lasted longer—overnight, for example—and were often described as opportunities for men to experiment with sexual practices they had seen in pornographic videos. By contrast, time was a luxury that men said they did not have during their liaisons in Tari. There were no brothels in Tari; thus, most illicit sexual transactions occurred outdoors and entailed ducking off into roadside underbrush without being seen and quickly completing the act before being caught. As one man said, “We can’t take the time to do different styles of sex. What if someone should come by and find us? We have to do it very quickly. If we could do it in a house somewhere, it would be all right. But we’re just there in the bush or just off the road. And if we were caught, it would be much worse to be caught doing some kind of untraditional style.” Many of the men said the anxiety about being caught and the consequent need to finish quickly also deterred them from using condoms.22

Men’s extramarital liaisons were primarily shaped by 4 interlocking factors: (1) the role of male mobility and migration in creating social contexts in which extramarital sexual relations are the norm, (2) the significance of bride wealth (goods given by the groom’s family to the bride’s family to formalize a marriage and to compensate for the loss of her labor and fertility) in shaping the social constructions of marriage and infidelity, (3) the growing pool of sexually available and “safe” women caused by local economic decline and men’s long-term absences from home, and (4) the homosocial nature of Huli sociality, i.e., men find it difficult to spend time at home and far easier to spend time with male friends.

Male Mobility and Labor Migration

Migration outside of Tari, whether for work or some other purpose, seemed to all but guarantee men’s extramarital sexual relationships.23 For example, when asked whether they had ever had extramarital relationships, the bus and truck drivers in the sample responded, “Of course, I’m a driver!” They spoke candidly about not only sexual liaisons with commercial sex workers along their routes but also exchanging transport for sexual relations with women who could not afford to pay their fares. Additionally, most men in the sample took the occasional trip to larger towns, the closest of which is about a 6-hour bus ride away and typically requires a stay of at least 1 night. Men often described the process of becoming familiar with a new urban area as an almost ritualized event that involved being taken to bars by urban-based kin or friends and then bringing women they met at the bars back to low-cost guest houses for sexual relations. Taking visitors or new urban arrivals to bars and paying for the beer and women is a way for male hosts to provide hospitality, and accepting these gifts enables new arrivals to experience modern urban masculinity.24

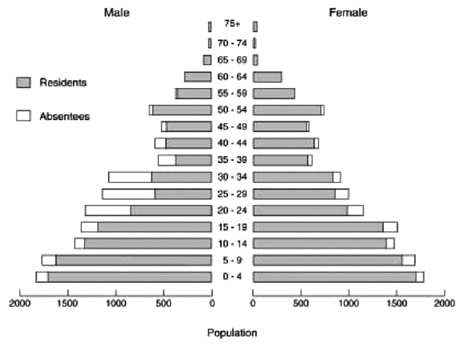

In addition to their brief trips, many men in the sample had worked outside of Tari. There have long been high rates of labor-related migration among the Huli men, in part because of colonial period economic policies that were designed to shape Southern Highlands Province into a labor pool for coffee, tea, and copra plantations located in other provinces.25 Migration data for 1982, for example, show that in some areas around Tari, approximately 45% of men aged 20 to 39 years were absent from their homes (Figure 1 ▶).26 Lack of economic opportunity, the extension of a paved road to Tari in the 1980s, and daily plane service have contributed to continuing high rates of men’s labor-related migration, these days to work at mine sites more often than plantations.

FIGURE 1—

Tari-area population pyramid indicating age and sex of absentees: Tari, Papua New Guinea, 1982.

Source. Lehman.26

This kind of long-term labor-related migration is associated with extramarital sexual relationships and with what might be called men’s extramarital sexual debut.27 As one man said, “After I was married, I left my wife and children and went to Goroka for work, and it was there that I had sex with another woman. That was the first time. I went with another man. It was his idea—he was my boss and I was the driver. He said, ‘Let’s go around and find some women. I’ll pay for some food and I’ll pay for the guest house.’ So I did this the first time because I was with him. We took a car and we went together. We impressed the women by riding around in a car. Lots of working men do this—they pressure each other to go drink and have sex with prostitutes.”

Men’s narratives of the extramarital liaisons they had had during the course of labor-related migration typically emphasized both missing their families and feeling an exhuberant sense of freedom from community scrutiny. The narratives also told of predominantly male work places where drinking and paying for sexual relations was the norm at the end of a long and arduous work week and of the fact that women tended to target employed men by gathering outside popular bars on men’s paydays. As one man said, “Sex is like money; they are temptations. If a man offers you money, you don’t say no. How can you make yourself say no when he is holding out his hand and giving it to you? The same is true when a woman offers to have sex with you. You just say yes.”

Men often expressed ambivalence about this form of relaxation: on the one hand, they found the male camaraderie and the attention of women fun and relaxing; on the other hand, many expressed guilt and anxiety about spending their money on such fleeting pleasures when they could have sent the money home to their families. In other words, many men expressed a strong sense of loyalty to wives; however, this loyalty was demonstrated primarily through material support, not sexual fidelity. Moreover, because labor migration was the context for many men’s first forays into extramarital sexual relations, it enabled them to experience it in a particular way—as a kind of exciting yet inconsequential leisure activity that men do together as members of male peer groups.

Bride Wealth and the Social Constructions of Marriage and Infidelity

The interviews revealed clear generational differences in Huli men’s social constructions of marriage. Men in the grandparent generation expressed what might be described as a paternalistic and managerial, but often fond, orientation toward their wives, and men in the newly married generation articulated a marital model that focuses more on the emotional quality of the relationship. For example, men were asked, “What do you do to be a good husband? In other words, in your own opinion, what do men need to do so that they will have good marriages?” Typical of the older generation was this quote from a 72-year-old participant, who had 3 concurrent wives at the time of the interview:

Women expect that a man will have enough land to divide evenly among his wives, enough pigs so that they all have some to raise, and that he will provide protection for his wives and children. If a man does this equitably, his wives will think he is a good man. . . . A woman shouldn’t feel like a slave—she should know that the work she does raising pigs and growing sweet potatoes will benefit her own kin when they are in need.”

As this quote suggests, older men in the sample emphasized the importance of women’s agricultural labor and maintaining good relations with a wife’s extended family in order to have a wide range of political alliances and economic resources. Moreover, many older husbands assumed that their wives’ primary emotional attachments and loyalties would be to their own natal kin, even after years of marriage.

By contrast, when the same question was asked of men in the middle-aged and newly married generations, the following quote was characteristic of their answers: “Before I speak to her, I think about what I need to say to her that will make her happy, how I should express something in a way that she will understand and accept. . . . If I do this, then she will have empathy for me and I will have empathy for her. Even if I can’t give her money or food, we will still get along if we are communicating well and if I speak kindly to her.”

Men in the newly married and middle-aged generations also were more likely than men in the grandparent generation to say that if they learned a joke, some gossip, or some important news, they would most want to share this with a wife rather than with male friends, which is another indication of the increased emotional centrality of the marital relationship. Thus, middle-aged men and particularly newly married men tended to describe their marriages in ways that resemble social scientists’ descriptions of companionate marriage, with its emphasis on emotion and verbal communication.28 This apparent generational change in ideologies about marriage is likely because of the younger generation’s greater exposure to Christian missionary teachings, formal education, and popular media.

Nevertheless, regardless of generation or socioeconomic status, almost all the men in the study emphasized the importance of bride wealth in determining spouses’ obligations to each other and, in particular, justifying a man’s authority over his wife. During their interviews, Huli men from all generations repeatedly invoked bride wealth as an explanation for why wives were expected to do more agricultural labor than their husbands were, why wives had to ask permission to leave the household, why wives had to comply when a husband requested sexual relations, and why wives had to obey a husband’s explicit instructions, such as fetching something when asked. If anything, the importance of bride wealth has intensified in the contemporary context because of its inflation and because many families now expect some of it to be paid in cash rather than with pigs, as has been the traditional custom. Two consequences of this change are that young, unemployed men now find it very difficult to acquire a wife, and once married, husbands often expect obedience from wives as a kind of recompense for the hardships they endured and the debts they incurred amassing the money for bride wealth.29

The interviews also showed that bride wealth shapes the social and moral meanings of extramarital sexual relations. For example, some men asserted that fidelity was expected of their wives because of the bride wealth that was given for them, but fidelity was not expected of men because they were the givers of bride wealth. Additionally, men said bride wealth distinguished which women were sexually off-limits because they “belonged” to their husbands. Once a man had given bride wealth to his wife’s family, it was understood that he had sole claim to her sexual and reproductive body. Thus, bride wealth is as much a compact between men as it is a tie of obligation between husband and wife, and marital infidelity—at least with married women—was described by most men in the sample as a transgression against other men. This male compact is enforced by the threat of violence: adultery, which in the Huli language literally means stealing a man’s wife, can lead to not only punitive violence against the wayward wife but also retaliatory violence against her male partner and his clan. Thus, although some men in the sample—particularly men in the middle-aged and newly married generations—described extramarital sexual relations as a transgression against one’s wife, they expressed more fear about the potentially deadly responses from the clansmen of their extramarital partners. When asked what the possible consequences were if a man had extramarital sexual relations, the most common answers were “tribal warfare,” “being taken to village court,” and “having to pay compensation to a woman’s husband.” Anxieties about damaging one’s marriage or a wife’s feelings were less common.

An important consequence of this conceptualization of marital infidelity is that as long as a man’s extramarital sexual liaisons do not infringe upon other men, little moral disgrace and few social or economic penalties are attached to the liaisons. As many men said, it is only common sense for a man to avoid marital discord through secrecy about his extramarital liaisons, but he has a moral obligation to protect his kin from tribal fighting and compensation claims by choosing “safe” partners—traditionally, widows and divorced women. This construction of what constitutes a safe partner clearly departs from the standard biomedical definitions of safe sexual relations.

Women Who Don’t Belong to Anyone

This social construction of infidelity, men’s absence from their communities because of labor migration, and the economic decline of the last 10 years have resulted in a pool of “safe” women in Tari who have sexual relations in exchange for money. Traditionally, the only safe extramarital female partners were widows and divorced women, i.e., women who occupied a liminal social position because their earlier marriages had removed them from the custody of their fathers but their divorces or spouses’ deaths meant that they were no longer in the custody of husbands. However, there is now another group of safe women—specifically, sex workers and women who engage in transactional sexual relations; locally, they are collectively referred to as passenger women.30 The following quote was typical of what men had to say about their safe extramarital partners: “I have been careful not to have sex with married women. I wanted to avoid any trouble with other men, and so I’ve had sex with divorced women or widows. I’ve also avoided young women who had reputations for being well controlled by their parents or brothers. Usually, I just try to find passenger women. You know—women who don’t belong to anyone.”

Despite the last part of that quote, many of the women that men refer to as passenger woman are officially married and thus do actually “belong” to someone. In other words, bride wealth was given for them, they have had children with their husbands, and neither they nor their husbands have sought a divorce. However, many of these women know or suspect that they have been abandoned by husbands who left Tari to find work. Some women learn from returning migrants that their husbands have established new households elsewhere with other female partners; others strongly suspect that they have been abandoned because they have not seen or heard from their husbands in months or even years.31 In fact, absentee men’s silence does not always mean they have absconded. Many men stated in their interviews that even when they had the opportunity to send messages home, they were too ashamed to do so if they were unable to send their wives money as well.

Passenger women themselves cited a wide range of motivations for engaging in transactional sexual relations: lack of money for children’s school fees and other necessities, encouragement from female kin to actively search for a new husband rather than waste fertile years waiting for an existing one to return, and a desire for retaliatory sexual relations upon learning that a husband has taken up with another woman elsewhere. The inflated cost of goods and services and a decrease in economic opportunities have exacerbated this situation. As one man said, “We would have to blindfold ourselves not to see all the willing women here now.”

Heterosocial Households and Homosocial Peer Groups

Although men’s extramarital sexual liaisons were clearly tied to their mobility and migration experiences, it also is important to note that for many men, extramarital sexuality does not stop upon returning home. The literature on migration and men’s extramarital sexuality sometimes seems to bracket off men’s episodes of labor migration, as if the episodes had no enduring consequences for men’s gender identities or sexual behaviors at home. However, many of the interviews in this study suggest that labor migration initiated men into a culture of masculinity in which extramarital sexuality was considered normal, modern, and an expression of male autonomy; thus, it set in motion an enduring pattern of extramarital sexuality.

This pattern is buttressed by the homo-sociality of adult life among the Huli, which makes many men feel out of place in their own households and results in men’s leisure time being spent with male peers. Most married couples now live together in the same house, which is a significant departure from the precolonial period when adult men who belonged to the same clan typically lived together in an all-male residence. However, this change in living arrangements does not necessarily mean that men are completely comfortable inhabiting what are usually referred to as family houses.32 Although most men in all the generational groups said they enjoyed the company of their wives, and some said that they preferred the company of their wives to other people, most men also expressed discomfort and irritation with having to stay for extended periods in the family house, particularly as the number of children in the household grew and the wife became absorbed in the labor of being a mother.

Men also commented, often unhappily, on the changes they observed in their wives once they had had 3 or more children. Specifically, wives were said to become more willful, demanding, and quarrelsome. As one middle-aged man said, “When women have children, there are changes. Before, my wife was young and she never talked back. She just sat there and agreed with me and laughed at my jokes. But once she had children, she decided that she was a citizen—that she had the right to speak, the right to carry a stick and hit me when she was angry, the right to disagree with me. She really thought she was a citizen. And when we had children, she got very busy with the children and only thought about them, and they were always around crying or demanding something. This would get on my nerves, and I lost interest in being at home with my wife.”

Such changes are not surprising when they are understood in terms of how women’s social power changes during the course of the life-cycle: women gain authority not from being good emotional and erotic companions to their husbands but through bearing and raising children. Having children gives them the legitimate right to make demands of their husbands, and it gives them some leverage for refusing requests made by their husbands. Thus, women can be seen as patiently biding their time, and perhaps biting their tongues, until childbearing enables them to be more forthright. Huli men tend to “biologize” these changes, by describing women as “naturally” docile when they are young and then as “naturally” becoming more querulous because of physiological changes associated with reproduction. Discretely seeking out alternative sexual partners at this juncture in a marriage was described as normal, harmless, and even beneficial for the marriage—certainly wiser than attempting to demand sexual activity from a tired and irritable wife.

Spending more time with male peers also was expected at this point in a man’s marriage, and boasting about extramarital liaisons, exchanging information about women, and spending Friday nights drinking and looking for available women were important components of masculinity and male friendship, which is seen in these 2 quotes:

“Yes, I boast to my friends—it’s something I show off about. I get very graphic. I say, ‘This woman is willing to do this and that’ or ‘This woman’s genitals looked like this’ or ‘That woman’s genitals felt like this.’ We all talk about women in this way.”

“Yes, I boast about this to my male friends. I tell them when I’ve had sex with another woman and what we did together. And sometimes I tell my friends what she’s like, what she is willing to do, how much you have to pay her. And then my friends can go ask her for sex. But I know that I got there first and was able to tell them all about it.”

Condom Use

Although the immediate concerns of many men in this study were to minimize the potential negative sociopolitical consequences of extramarital sexual relations by choosing “safe” partners, they also sometimes used the English word safety to refer to condoms, and most were aware of the possibility of marital transmission of sexually transmitted infections and HIV. They expressed a range of attitudes toward condoms, with a few saying they used them scrupulously, a few saying they never used them and did not intend to, and most saying they used them sometimes. Most of the men volunteered lack of access as a substantial obstacle to use. Because of the dominant social conservatism of the community, local stores do not sell condoms, and many men expressed shame about asking for them at the hospital, where the staff were known to be reluctant distributors.33 Most men in this sample relied on what might be called an underground informal condom economy, in which some men stocked up on condoms from health centers and pharmacies in larger towns and then sold them surreptitiously in Tari.

CONCLUSIONS

ABC approaches to AIDS prevention assume that marital sexual fidelity has an inherent moral value and is what all married people everywhere know they should be striving for at all times. By contrast, many Huli men consider extramarital sexual relations to be acceptable after a man has successfully established a family, and many assert that marital fidelity takes a toll on a marriage and that extramarital sexual relations are generally harmless. Labor migration often initiates men into a masculine subculture in which extramarital sex is overdetermined and all but inevitable. Moreover, sexual relations with sex workers is seen as unproblematic and safe, because passenger women “don’t belong to anyone.”

These findings show a range of arenas in which HIV risk reduction measures can be implemented. First, there must be greater recognition that men’s labor migration plays a large role in (1) initiating some men’s extramarital sexual debut, (2) immersing men in work site subcultures in which extramarital sexuality is seen as both normal and an important means for enacting modern masculinity, and (3) creating pools of women at home who are more likely to have sexual relations in exchange for money. The public health community has accumulated more than enough epidemiological and ethnographic evidence that shows men’s risk for HIV—and thus also their wives’ risk—is strongly associated with economic structures that require men to leave home to support their families and that put men into high-risk social environments.34 The risks seem especially pronounced when the work sites in question are resource extraction sites, such as mines, perhaps because of their predominantly male workforces and their arduous working conditions.35

The single most important recommendation is that employers should be encouraged to provide family housing for their workers who come from far away. Family housing would reduce the loneliness and sexual deprivation that some men said encourages extramarital sex; it would create a community—similar to that of the men’s home communities—that discourages risky practices through the everyday scrutiny of community members’ behavior, and it would decrease the number of married women who have sexual relations in exchange for money because of a husband’s prolonged absence. Recent research has suggested that family housing could significantly reduce the risk for HIV infection.36

There also is a need for more aggressive workplace AIDS education and condom distribution, particularly at work sites where a large percentage of the workforce is male and has emigrated. In countries like Papua New Guinea, where a long history of Christian missionization has made rural communities highly resistant to the social marketing of condoms, such workplace interventions are particularly important.37 The 4 male field assistants in the study stressed the importance of promoting structured recreational activities for men—both at work sites and in home communities—such as sports teams, literacy and vocational training classes, and political discussion groups.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the structural nature of men’s extramarital sexual behavior. Interventions that promote fidelity appear to make certain assumptions about the marital relationship, such as the universality of a Western model of companionate marriage or, more fundamentally, that spouses are actually living together in 1 place. However, simply telling men to be faithful is not likely to be effective in the absence of a social infrastructure that makes fidelity more possible. Such infrastructure could certainly include faith-based initiatives, such as work-place support groups for male migrants or pastoral guidance for married couples that goes beyond the existing premarital counseling and that candidly acknowledges the many challenges to marital fidelity in resource-poor settings where economic opportunities are few and where men must often leave home to make a living. Socioeconomic initiatives that enable men to live at home or that enable wives to live with their migrant husbands also are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 HD041724).

Many thanks to my field assistants Ken Angobe, Luke Magala, Thomas Mindibi, and Michael Parali; the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research; the Papua New Guinea National AIDS Council, especially John Milan and Joachim Pantumari; the Tari branch of Community-Based Healthcare, especially Joseph Warai; the Tari District Women’s Association, especially Jacinta Haiabe; Tari District Hospital, especially Sister Pauline Agilo; and the Tari community liaison office for Porgera Joint Venture, especially Geoff Hiatt and Simon Thomas. Special thanks to Mary Michael and June Pogeya for their insights, laughter, and friendship.

Human Participant Protection Ethical approval to conduct this research was obtained from the University of Toronto, Emory University, the Papua New Guinea National AIDS Council, the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, and the Papua New Guinea Medical Research Advisory Committee.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Foreman M, M. (ed.), AIDS and Men: Taking Risks or Taking Responsibility, (London: Panos Institute, 1999). Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United National Population Fund (UNFPA), and United National Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), “Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the Crisis.” (New York and Geneva: UNAIDS/UNFPA/ UNIFEM, 2004). United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), “Economic and Social Progress in Jeopardy: HIV/AIDS in the Asian and Pacific Region, ST/ESCAP/2251.” (New York: UNESCAP, 2003).

- 2.An older generation of ethnographic research demonstrated that cultural variations in marriage—the presence or absence of polygamy, dowry, or bridewealth, for example, or whether wives are expected to be more loyal to their husbands or to their own natal families—strongly correlate with specific economic and ecological factors. J. Goody, Production and Reproduction: A Comparative Study of the Domestic Domain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977). M. Meggitt, “Male-Female Relationships in the Highlands of Australian New Guinea,” American Anthropologist 66(1964):204–224. L. Langness, “Sexual Antagonism in the New Guinea Highlands: a Bena-Bena Example,” Oceania 37(1967): 161–177. More recent social science research has shown that the ideological importance of love and emotional intimacy within marriage also varies by cultural and economic context. See especially L. Rebhun, The Heart is Unknown Country: Love in the Changing Economy of Northeast Brazil (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999). J. Hirsch, A Courtship after Marriage:Sexuality and Love in Mexican Transnational Families (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

- 3.Shelton J., D. Halperin, V. Nantulya, M. Potts, H. Gayle, and K. Holmes, “Partner Reduction is Crucial for Balanced “ABC” Approach to HIV Prevention,” British Medical Journal 328(2004): 891–893. S. Cohen, “Promoting the ‘B’ in ABC: Its Value and Limitations in Fostering Reproductive Health,” The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy 7(2004): 11–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For more on the history and nature of companionate marriage see A. Giddens, The Transformation of Intimacy: Love, Sexuality and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993); D. Shumway, Modern Love: Romance, Intimacy, and the Marriage Crisis (New York: New York University Press, 2003); and J. Hirsch and H. Wardlow, eds., Modern Loves: the Anthropology of Romantic Courtship and Companionate Marriage (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006).

- 5.The author recognizes that women can also experience material and (perhaps less often) ideological pressures that diminish the value or practicability of marital sexual fidelity; however, this article focuses on the socioeconomic factors that promote men’s extramarital sexuality.

- 6.Duke T., “Decline in Child Health in Rural Papua New Guinea.” The Lancet. 354(1999): 1291–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS at Country Level Progress Report, 2004.

- 8.Malau C. and S. Crockett, “HIV and Development the Papua New Guinea Way,” Development Bulletin 52(2000): 58–60. M. Passey, “Community Based Study of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Rural Women in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea: Prevalence and Risk Factors,” Sexually Transmitted Disease 74(1998): 120–127. S. Tiwara et al., “High Prevalence of Trichomonal Vaginitis and Chlamydial Cervicitis among a Rural Population in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 39(1996): 234–238. H. Wardlow, “‘Giving Birth to Gonolia’: ‘Culture’ and Sexually Transmitted Disease among the Huli of Papua New Guinea, Medical Anthropology Quarterly 16(2002): 151–175. J. Hughes, “Sexually Transmitted Infections: a Medical Anthropological Study from the Tari Research Unit, 1990–1991,” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 45(2002): 128–133. J. Hughes, “Impurity and Danger: the Need for New Barriers and Bridges in the Prevention of Sexually-Transmitted Disease in the Tari Basin, Papua New Guinea,” Health Transition Review 1(1991): 131–140. L. Hammar, “Sexual Health, Sexual Networking and AIDS in Papua New Guinea and West Papua,” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 47(2004): 1–12. L. Hammar, “Caught between Structure and Agency: Gendered Violence and Prostitution in Papua New Guinea,” Transforming Anthropology 8(1998): 77–96.12179454 [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Papua New Guinea currency, the kina, had been pegged to the US dollar, but in 1995, the kina was floated as part of an economic reform program developed in consultation with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Beginning in 1997, the kina, then worth approximately US 85 cents, crashed in value until it reached an all-time low, in 2002, when it was worth about US 19 cents. In 2004, when the research for this article was carried out, the kina was worth US 27 cents.

- 10.In Papua New Guinea, Tari has a reputation for being more crime-ridden than other towns of its size. During the research for this article, there was 1 local gang that repeatedly abducted figures of authority and held them for ransom. One consequence was that a number of organizations—including the National AIDS Council—refused to send representatives there. While Tari may have been exceptional in terms of crime at that time, it was not exceptional in terms of declining public services. Stores, bank branches, health centers, and primary schools in other small towns also closed during the late 1990’s and early 2000’s.

- 11.At the time of the research for this article in 2004, few tests were being done because the hospital’s microscope had been stolen, the hospital dispensary was short of essential medicines, and many hospital staff had fled the area because of election-related violence and an escalation in crime in 2002. Key informant interviews with hospital staff, youth group leaders, and religious leaders suggested that many people traveled to the provincial capital, Mendi, a 6-hour bus ride away, to be tested for HIV, hoping for more anonymity and faster test results in cities with larger hospitals.

- 12.According to her descriptions, the remaining 12 female cases consisted of unmarried sex workers who had likely been infected through selling sex; married women who had probably been infected before marriage, when they were students, for example; and married women who had been infected through their own extramarital liaisons, either when their husbands were absent for wage-labor or when they were separated from their husbands because of marital conflict.

- 13.Glasse R. M., Huli of Papua: A Cognatic Descent System (Mouton & Co., Paris, 1968). R.M. Glasse, “Le Masque de la Volupté: Symbolisme et antagonisme Sexuels sur les hauts plateaux de Nouvelle-Guinée,” L’Homme 14(1974):79–86. S. Frankel, “‘I am Dying of Man’,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 4(1980): 95–117. S. Frankel, The Huli Response to Illness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). L. Goldman, Talk Never Dies: the Language of Huli Disputes (London: Tavistock, 1983). H. Wardlow, Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). J. Clarke and J. Hughes, “A History of Sexuality and Gender in Tari,” in Papua Borderlands: Huli, Duna, and Ipili Perspectives on the Papua New Guinea Highlands, ed. A. Biersack. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995, 315–340).

- 14.Traditionally, Huli men were taught to monitor their wives’ menstrual cycles and only engage in sex with them on a few consecutive days after menses ended (S. Frankel, “‘I am Dying of Man’,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 4(1980): 95–117. S. Frankel, The Huli Response to Illness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). In fact many men of the older generation and some men in the middle-aged generation in the current study still follow this custom, and they volunteered this information to explain why certain interview questions—e.g., “How often do you have sex with your wife—is it approximately once per week, more often than this, or less often?”—did not make sense to them. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.In Tari, the principle churches are the Catholic Church, United Church, Seventh Day Adventists (SDA), and Evangelical Church of Papua New Guinea, all of which established missions in Tari not long after it was established as an Australian colonial government station in the late 1950’s.

- 16.Fewer participants of high assets and economic resources were included in the study primarily because few people of high socioeconomic status live in Tari. Further, of the high assets participants recruited to the study, none could be found who did not have postmarital migration experience.

- 17.The other 4 investigators and research sites were: Jennifer Hirsch, Mexico; Shanti Parikh, Uganda; Harriet Phinney, Vietnam; and Daniel Smith, Nigeria. The project as a whole is entitled “Love, Marriage, and HIV: A Multi-Sited Study of Gender and HIV Risk.”

- 18.The discipline of cultural anthropology has long recognized that not all communities or individuals will be amenable to the research methods that social scientists utilize in order to standardize results and maximize comparability. Thus, ethnographers typically employ multiple methods to obtain data on any 1 research question, both in order to crosscheck and verify data and because the nature of research with human subjects often necessitates flexibility in data collection.

- 19.Glasse R. M., Huli of Papua: A Cognatic Descent System (Mouton & Co., Paris, 1968). R.M. Glasse, “Le Masque de la Volupté: Symbolisme et antagonisme Sexuels sur les hauts plateaux de Nouvelle-Guinée,” L’Homme 14(1974):79–86. S. Frankel, “‘I am Dying of Man’,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 4(1980): 95–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Some female interview participants said that if they experienced unusual fatigue or malaise, they often suspected a husband’s infidelity. This belief is not attributed to disease transmission (although many women are also familiar with biomedical understandings of sexually transmitted infections and HIV transmission); rather, a man’s infidelity is described as a form of pollution that contaminates his wife and children.

- 21.Newly married men with fewer than 3 children and religiously devout men who held official positions within their church congregations were the exceptions and had not engaged in extramarital sex—the former because of fears of endangering a wife’s health and fertility, and the latter because of anxiety about the public disgrace of not living up to the behavioral standards expected of church representatives.

- 22.The fleeting and often anonymous nature of men’s extramarital relationships has been documented elsewhere in Papua New Guinea (L. Hammar, “Sexual Transactions on Daru: With Some Observations on the Ethnographic Enterprise,” Research in Melanesia 16(1992):21–54. L. Hammar, “Bad Canoes and Bafalo: The Political Economy of Sex on Daru Island, Western Province, Papua New Guinea,” Genders 23(1996):212–43. The National Sex and Reproduction Research Team (NSRRT), and C. Jenkins, Sexual and Reproductive Knowledge and Behaviour in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research Monograph No. 10. Goroka: Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, 1994.) However, this finding likely also reflects the research site and the sample of men interviewed: Tari is quite rural and small, and it would be impossible to maintain an extramarital relationship for long without its being discovered. Moreover, most of the men in the sample were of low socioeconomic status and could not afford to economically support another woman. [Google Scholar]

- 23.See also Campbell C., “Migrancy, Masculine Identities and AIDS: The Psychosocial Context of HIV Transmission on the South African Gold Mines,” Social Science and Medicine 45(1997): 273–281. J. Hirsch, J. Higgins, M. Bentley, and C. Nathanson, “The Social Constructions of Sexuality: Marital Infidelity and Sexually Transmitted Disease-HIV Risk in a Mexican Migrant Community,” American Journal of Public Health 92(2002): 1227–1237. M. Turshen, “The Political Ecology of AIDS in Africa” in The Political Economy of AIDS, ed. M. Singer. (Amityville, N.Y: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., 1998, 167–82). B. Williams, E. Gouws, M. Lurie, J. Crush, Spaces of Vulnerability: Migration and HIV/AIDS in South Africa, Migration Policy Series #24, Southern African Migration Project, Queen’s University, Canada, 2002. D. Brummer, Labour Migration and HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa, Report prepared for the International Organization for Migration, 2002.9225414 [Google Scholar]

- 24.See also Nihill M., “New Women and Wild Men: ‘Development,’ Changing Sexual Practice and Gender in Highland Papua New Guinea,” Canberra Anthropology 17(1994): 48–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris G.T., “Labor Supply and Economic Development in the Southern Highlands,” Oceania 43: 123–139. J. Vail, “Social and Economic Conditions at Tari,” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 45(2002): 113–127, 1972. [PubMed]

- 26.Lehman D., “Demography and Causes of Death among the Huli in the Tari Basin,” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 45(2002): 51–62. See also D. Lehman, J. Vail, P. Vail, J. Crocker, H. Pickering, M. Alpers, and the Tari Demographic Surveillance Team, Demographic Surveillance in Tari, Southern Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea: Methodology and Trends in Fertility and Mortality between 1979 and 1993 (Goroka, Papua New Guinea: Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, 1997). From 1970 to 1995, a demographic database was maintained by the Tari Research Unit, a branch of the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, through a system in which Huli men were hired to keep track of 500–1000 people on their own clan territories and report all demographic events monthly. This demography was shut down in 1995 due to lack of funds and increasing crime and tribal fighting in the Tari area. More recent data than is provided in Table 2 is not available because the data compiled by the project has not been analyzed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Public health practitioners have worked on delaying young people’s sexual debut with the aims of (1) shortening the period of exposure to sexually transmitted infections and HIV (2) diminishing the number of lifetime sexual partners, and (3) giving young people the opportunity to mature and to gain the education, life-skills, and relative security that might enable them to make safer sexual choices. Implicit in some of this work is the notion that the nature and social context of a person’s first sexual experience can influence the sexual choices they subsequently make. Thus, for example, if a young woman’s first sexual experience is of a commercial nature and made in a context of desperation among female peers who are making similar choices, this pattern may endure. I am suggesting here that the nature and context of men’s first extramarital sexual experiences (for example, commercial sex, far from home, surrounded by one’s drunk male peers) may similarly influence their subsequent sexual choices.

- 28.Giddens A., The Transformation of Intimacy: Love, Sexuality and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993). J. Finch and P. Summerfield, “Social Reconstruction and the Emergence of Companionate Marriage, 1945–49,” in Marriage, Domestic Life and Social Change, ed. D. Clark (New York: Routledge, 1991). F. Cancian, Love in America: Gender and Self-Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- 29.Bride wealth among the Huli was 15 pigs in the 1960’s, and is now about 30 pigs. However, most families now prefer to receive some portion of the bride wealth payment in cash (H. Wardlow, Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society). The inflation and monetization of bride wealth payments is a widespread phenomenon and is not confined to Papua New Guinea. For analyses of this phenomenon and its often deleterious social consequences see: J.I. Guyer, “The Value of Beti Bridewealth” in Money Matters: Instability, Values and Social Payments in the Modern History of West African Communities, ed. J.I. Guyer (Portsmouth: Heineman, 1995, 113–132). A. Jasquelier, “The Scorpion’s Sting: Youth, Marriage and the Struggle for Social Maturity in Niger,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11(2005): 59–83. M. Fleisher and G. Holloway, “The Problem with Boys: Bridewealth Accumulation, Sibling Gender and the Propensity to Cattle Raiding among the Kuria of Tanzania,” Current Anthropology 45(2004): 284–288. B.L. Shadle, “Bridewealth and Female Consent: Marriage Disputes in African Courts, Gusiiland, Kenya,” Journal of African History 44(2003): 241–62.

- 30.Wardlow H., “Anger, Economy and Female Agency: Problematizing ‘Prostitution’ and ‘Sex Work’ in Papua New Guinea. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 29(2004): 1017–40. H. Wardlow, Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). H. Wardlow, “Headless Ghosts and Roving Women: Specters of Modernity in Papua New Guinea,” American Ethnologist 29(2002): 5–32. H. Wardlow, “Passenger Women: Changing Gender Relations in the Tari Basin,” Papua New Guinea Medical Journal 45(2002): 142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Women’s suspicions are probably exacerbated by the breakdown in public services; for example, the closure of the Tari post office has meant that absentees from the community cannot send letters or wire money home.

- 32.Significantly, men sometimes refer to “family houses” as their “wives’ houses,” suggesting that many men feel not that they have created a new kind of domestic and marital space—as the Christian missionaries who promoted this change probably intended—but instead have moved into a female space.

- 33.A few older men said that they wanted to educate younger men about condoms but also said that without more institutional support they would not be courageous enough to do so because of the pervasive stigma associated with condoms.

- 34.Anarfi J.K., “Sexuality, Migration and AIDS in Ghana—a Socio-Behavioral Study,” in Ed. J.C. Caldwell, Sexual Networking and HIV/AIDS in West Africa, supplement to Health Transition Review 3(1993): 45–67. B. Girdler-Brown, “Migration and HIV/AIDS: Eastern and Southern Africa,” International Migration 36(1998): 513–515. M. Brockerhoff and A.D. Biddle-com, “Migration, Sexual Behavior, and the Risk of HIV in Kenya,” International Migration Review 33(1999): 833–856. M. Lurie, “Migration and AIDS in Southern Africa: A Review,” South African Journal of Science 96(2000): 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams B., E. Gouws, M. Lurie, and J. Crush, “Spaces of Vulnerability: Migration and HIV/AIDS in South Africa,” Migration Policy Series #24, 2002, Southern African Migration Project, Queen’s University, Canada. M. Lurie, A. Harrison, D. Wilkinson, and S.A. Karim, “Circular Migration and Sexual Networking in Rural KwaZulu/Natal: Implications for the Spread of HIV and other Sexually Transmitted Diseases,” Health Transition Review Suppl 3 to volume 7(1997): 17–27. C. Campbell, “Migrancy, Masculine Identities and AIDS: the Psychosocial Context of HIV Transmission on the South African Gold Mines,” Social Science and Medicine 45(1997): 273–281.T.D. Moodie and V. Ndatshe, Going for Gold: Men, Mines and Migration, 1994, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 36.Gebrekristos H.T., C. Stephen, K. Zuma, M. Lurie, “Estimating the Impact of Establishing Family Housing on the Annual Risk of HIV Infection in South African Mining Communities,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 32(2005): 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeiffer J., “Condom Social Marketing, Pentecostalism, and Structural Adjustment in Mozambique: A Clash of AIDS Prevention Messages,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 18(2001): 77–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]