Introduction

A large number of drugs are eliminated to a clinically important degree by the kidney. For many drugs, this means that in patients with decreased renal function, doses need to be decreased to avoid exposure of the patient to excessive drug concentrations that may cause toxicity. In general, if 30% or more of a drug's total clearance is dependent on the kidney, dose reduction should be considered in patients with decreased renal function. Thus, it is important early in drug development to quantify the renal contribution to overall drug elimination. If a drug is eliminated by the kidney, it is necessary to determine the pathways of elimination; for example, glomerular filtration, as opposed to active secretion. If the latter process operates, in addition to the need to decrease doses in patients with diminished renal function, there is also a likelihood of drug interactions that must be considered in labelling and clinical use.

During development of a drug, there occasionally will be a change in renal function raising the question of nephrotoxicity. Sometimes such effects are indeed adverse renal effects; sometimes it is a functional effect such as inhibition of the secretion of creatinine [1, 2] or it may cause a false positive renal screening test. In the former case, development may cease; the latter simply dictates a need to inform clinicians of the risk of a false positive renal test.

A host of methods, both in vivo and in vitro, have been employed to determine renal function accurately and to assess mechanisms of renal elimination of drugs.

Measuring renal function

A variety of tests are used clinically to measure renal function. In drug development these tests are best viewed as screening in nature. Net renal function is assessed clinically by measurement of serum creatinine or blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentrations and, on occasion, measurement of creatinine clearance. The inaccuracy of these markers derives from the fact that their renal elimination is not purely by filtration at the glomerulus [1–6]. Creatinine has a secretory component of elimination that is about 15% of total excretion in subjects with normal renal function, and which is even greater in patients with decreased renal function. Thus, an increase in serum creatinine can occur from either a decrease in overall renal function (GFR) or because a drug has blocked its secretion. The implications of these two scenarios differ markedly. Urea is not only filtered but is also reabsorbed by the proximal nephron [7]. In conditions of increased proximal tubular reabsorption of solute including a variety of oedematous disorders, BUN rises, but this increase is not due to a decrease in global renal function per se.

Because of the limitations of these clinical indices of renal function, considerable research has been devoted to the identification and validation of better markers of renal function. Some of these are listed in Table 1[8–15]. However, many limitations remain. Even with these markers, a variety of methods can be employed when using them. For example, and as will be discussed below, with any of the GFR markers one can use a single injection technique and measure marker disappearance rate. Alternatively, a continuous infusion of the marker can be given with collection of serial blood and urine samples to calculate renal clearance directly. When designing studies to assess renal function precisely, it is vitally important that not only is the best marker selected, but the best method for using the marker is used.

Table 1.

Markers of renal function.

| Glomerular filtration rate |

| Creatinine clearance when secretion is blocked; e.g. with cimetidine |

| Inulin |

| Iothalamate |

| Diatrizoate |

| Ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) |

| α2-microglobulin |

| Diethylene triamine pentacetic acid (DTPA) |

| 2-(α-mannopyranosyl)-L-tryptophan (MPT) |

| Renal blood flow |

| Para-aminohippurate (PAH) |

| N-methylnicotinamide (NMN) |

| Iodohippurate |

| 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid |

Methods for assessing renal function and renal drug elimination [16, 17]

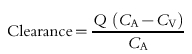

A general expression for assessing the clearance of any substance across an organ is given by equation 1.

|

(1) |

where Q = blood flow, CA = concentration of the substance of interest in the arterial circulation, and CV = concentration in the venous effluent. Applying such a method to define renal clearance of a marker or a drug in man is difficult because of the invasiveness of the procedures needed to quantify the variables in the equation. As a result, other methods have been developed.

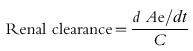

An alternative approach to measuring renal clearance is to relate the rate of excretion of the marker or drug to its plasma concentration (equation 2).

|

(2) |

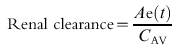

where Ae is the amount excreted in the urine at time t, and C is the plasma concentration. This equation refers to the instantaneous amount of drug excreted at a specific time and the plasma concentration at that specific time. Since the former cannot be determined directly, the amount of drug excreted within a specific time interval is measured and related to the average plasma concentration (CAV) during that time interval (equation 3).

|

(3) |

This expression is equivalent to that used clinically for measuring creatinine clearance (equation 4).

| (4) |

where U is the concentration of creatinine in urine, V is urine excretion rate, and P is the plasma concentration of creatinine.

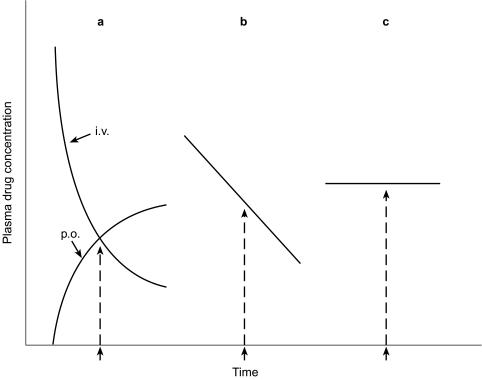

Experimentally, CAV is often assumed to be approximated by the plasma concentration at the midpoint of the urine collection interval. This assumption can be erroneous if the plasma concentration is changing in a nonlinear fashion, as typically occurs after intravenous bolus administration of a marker or drug or during the absorptive phase of a drug given by mouth. The schematic in panel a of Figure 1 illustrates this potential problem wherein the midpoint plasma concentration is clearly not the average concentration during the interval specified. In contrast, panel b of Figure 1 depicts an example where the change in plasma drug concentration over the duration of the collection interval is linear wherein the midpoint plasma sample is representative of the average concentration. These same considerations apply when markers are used to quantify renal function using a single injection technique followed by measuring only plasma disappearance of the marker. On the one hand, if the marker is only filtered, if renal function is stable, and if the disappearance curve is linear, then this method is both simple and yields accurate measures of GFR. On the other hand, if any of these assumptions is violated, then the single injection method is flawed. As noted previously, care must be taken to select the best method for the marker or drug and the condition in which it is studied. Lastly, panel c depicts a method in which any problems related to nonlinearity are avoided by administering the substance as a continuous intravenous infusion to achieve steady-state plasma concentrations. Unfortunately, not all markers, particularly those that are radiolabelled, can be given over the lengths of time needed for this method and many drugs do not have an intravenous formulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic of different drug administration methods for determining the renal clearance of a marker or drug. Panel a shows plasma drug concentration-time curves after a single i.v. (descending curve) and oral (ascending curve) dose. Panel b shows a linear plasma drug disappearance curve. Panel c shows a constant plasma drug concentration at steady state during continuous i.v. infusion (from reference 16, with permission).

Another potential source of error in using measurements of the renal clearance of a marker or drug is in the urine collection itself [18]. If the subject/patient has a bladder catheter, the accuracy of the urine collection is less of an issue. However, urine is usually collected by spontaneous voiding. It goes without saying that the times of the collection must be accurate. In addition, the collection interval and urine volume must be sufficient to obtain an accurate collection such that urine flow can be started and the bladder can be as completely emptied as possible. Small urine volumes collected over short intervals are likely to be subject to considerable error. If short (e.g. 20–30 min) collection intervals are to be used, patients must receive sufficient fluids to assure urine volumes of several hundred millilitres. In this manner, even if residual urine volume is as high as 5 ml, any error would be small and unimportant.

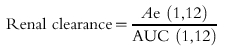

Because of the potential problems in the determination of renal clearance discussed above, an alternative method is often used based upon the intergral of equation 2:

| (5) |

where Ae is the total amount of drug excreted in the urine and AUC is the area under the curve of plasma marker/drug concentration vs time. This method can entail extrapolation to infinity or the values can be specified for a finite time interval:

|

(6) |

When employing this method, AUC is calculated using the trapezoidal method. If AUC is extrapolated to infinity, one must be certain that the extrapolated area is not a dominant proportion of the total AUC. If the extrapolated area is too high, an error in the extrapolation can introduce large overall errors. In general, the extrapolated area should be <10% of the total area. This method requires the added complexity of frequent blood sampling and assumes that marker or drug retained in the bladder over what may be long time intervals is not degraded or reabsorbed. If these assumptions are met, this method is the most accurate for determining renal clearance of a drug.

Note, that renal clearance in all of the preceding equations represents all components of renal clearance. For a substance like creatinine, it represents filtration clearance and secretory clearance. For some drugs it might represent filtration clearance plus secretory clearance less reabsorptive clearance. Thus, this value per se offers no mechanistic information as to the pathway(s) of renal excretion. On the other hand, if a marker is used that is only filtered, then renal clearance in these equations represents GFR. If, for example, a drug's renal clearance is quantified along with a valid marker of GFR, and the drug's renal clearance exceeds GFR, then one can reliably conclude that the drug of interest has a secretory component of elimination. Such data do not exclude filtration or reabsorption and do not quantify the secretory component, but they do allow the conclusion that secretion occurs.

Once the renal clearance of a drug is measured, inferences can be made concerning its mechanism of excretion. Since only unbound drug can be filtered, if renal clearance of unbound drug is equal to GFR, it can be assumed that all renal elimination is by filtration (unless secretion is exactly balanced by reabsorption). If renal clearance of unbound drug is less than GFR, then it can be assumed that the difference is accounted for by reabsorption. Such an observation may prompt additional studies to assess the influence of urinary flow rate and pH on the reabsorptive component. Lastly, if renal clearance of the unbound drug is greater than GFR, active secretion must be involved. Further assessment might entail additional studies with inhibitors of secretion to identify which secretory pathway is operative (thereby allowing prediction of potentially interacting drugs) and to quantify this component of renal elimination.

For many drugs, the studies mentioned above can only provide qualitative and semiquantitative data concerning the various components of renal excretion. It is often impossible in man to determine the precise quantitative contribution of the different pathways. For example, a drug might be filtered and secreted and then reabsorbed. Precise quantification of the magnitude of each component of elimination would require the ability to completely block one or more excretion pathways with assessment of the effect of such a manoeuvre on overall renal elimination. Such blockade is usually impossible. This fact notwithstanding, knowing qualitatively the mechanism of a drug's renal elimination can allow appropriate cautions and predictions as to the influence of renal disease and the potential for drug interactions, as will be discussed subsequently.

Renal drug elimination

A general rule of thumb is that for renal elimination to contribute meaningfully to overall drug elimination, the amount of drug excreted unchanged in the urine should be 30% or more of the dose.

Renal metabolism

There are two aspects of renal metabolism that invalidate the 30% rule. The proximal tubule has peptidases that are capable of digesting peptides and proteins. If a drug or polypeptide therapeutic agent is freely filtered at the glomerulus, the agent can be metabolized at the proximal tubule so that no or negligible amounts of agent appear unchanged in the urine. In fact, all excretion may be dependent upon the kidney, yet no unchanged drug is detected in urine at all.

A common example of this phenomenon refers to insulin. Renal metabolism accounts for approximately 30% of overall insulin elimination. Accordingly, in patients with severe renal insufficiency, insulin requirements are often decreased [19].

Another compound that undergoes renal metabolism is imipenem which is digested by dipeptidases after being filtered at the glomerulus [19]. This means that imipenem alone is not effective for treating urinary tract infections. Effectiveness is maintained clinically by administering imipenem in combination with cilastatin, a compound that inhibits proximal tubular dipeptidases, thereby allowing imipenem to escape proximal tubular metabolism and be effective as an antibiotic in the lower urinary tract.

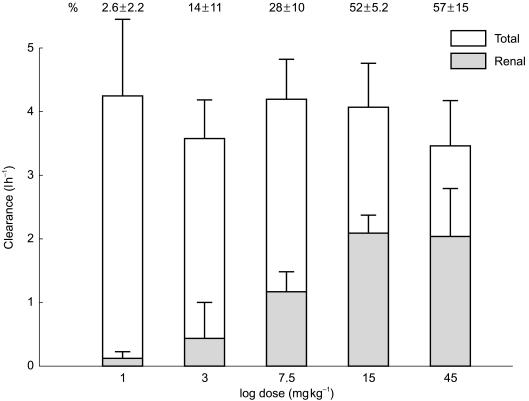

A third example is superoxide dismutase (SOD) [20]. Superoxide dismutase is a sufficiently small protein that it is freely filtered at the glomerulus, yet at low doses no SOD can be detected in the urine. This is because it is completely metabolized at the proximal tubule. As doses are increased, the metabolic capacity of the proximal tubule is exceeded, and SOD can be detected in the urine. Only at these higher doses can the contribution of renal clearance to overall clearance (Figure 2) be discerned. The clinical importance of this observation is that, based on the inability to detect unchanged drug in the urine, it might be concluded that the kidney plays no role in SOD disposition and that the protein is completely metabolized by the liver. To the contrary, a substantial component of SOD elimination depends upon the kidney, such that patients with decreased renal function will be at risk of accumulation of the protein and that dosage adjustment may be necessary. If such information had not been generated prior to efficacy trials, no provision for dosage adjustment would have been made for patients with decreased renal function. Such patients might then be exposed to higher concentrations than expected and suffer adverse events. Use of the drug might then appear to have risks much greater than would have been the case if the true pathways of elimination had been determined in early studies followed by appropriate protocol modification and dose adjustment in later phase trials.

Figure 2.

Clearance of superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a function of dose. Note that total clearance remains relatively constant while renal clearance as a percent of total clearance increases with dose. This occurs because at higher doses proximal tubular metabolism of SOD is overwhelmed allowing recovery of unchanged SOD in the urine and a more accurate assessment of the contribution of renal clearance. Estimates of renal clearance with low doses are inaccurate because the SOD cleared by the kidney never reaches the urine owing to proximal metabolism.

The phenomenon described with SOD likely applies to many if not most peptides, peptidomimetics and small proteins that are used or being developed. In fact, it should be presumed that any peptide or protein that is sufficiently small to be freely filtered at the glomerulus would have the same characteristics described for SOD and that specific studies should be performed to determine whether or not renal excretion is a significant component of overall elimination.

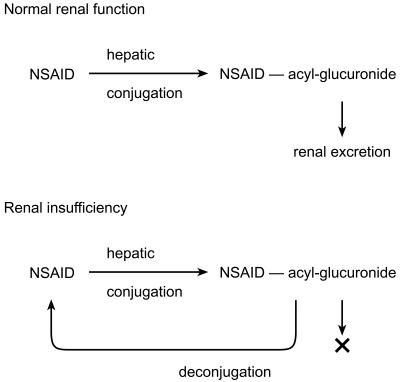

Another aspect of drug metabolism that can be misleading with respect to the importance of renal function in drug elimination is the phenomenon called ‘futile cycling’[21–24]. This occurs with drugs that are metabolized to acyl-glucuronides. Acyl-glucuronides are those where a carboxylic acid group in the parent drug molecule is conjugated through an ester linkage. Unlike ether glucuronides, ester glucuronides are chemically unstable, being readily hydrolysed, such that there is an equilibrium between parent drug and the acyl-glucuronide. Most glucuronides are excreted by the kidney. Thus in a subject with normal renal function an acyl-glucuronide would be formed in the liver, and this metabolite would be readily excreted into the urine. However, in patients with decreased renal function, excretion of the acyl-glucuronide is impaired, and it can accumulate in the plasma, where it spontaneously hydrolyses back to parent drug (Figure 3). The net result is an increase in circulating parent drug concentration and risk of adverse effects. The likelihood of such a ‘futile cycle’ should be expected with any drug where formation of an acyl-glucuronide metabolite is possible. Examples of such drugs include clofibrate, ciprofibrate, and a variety of arylpropionic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketoprofen [21–24].

Figure 3.

Schematic of a ‘futile cycle’ of drug metabolism where acyl-glucuronide metabolites are retained in patients with renal insufficiency. They are then able to spontaneously hydrolyse back to parent drug in the circulation resulting in its accumulation even though the parent drug per se undergoes no direct renal excretion.

Renal excretion

The kidney performs the physiologic functions of filtration, secretion and reabsorption. It is important to understand the implications of these different processes for drug handling. For example, filtration only refers to the fraction of circulating drug that is not bound to plasma protein. Secondly, filtration has size limitations owing to the dimensions of the glomerular pores and their electrical charge (negative). Size limitations are not relevant to traditional xenobiotics, but are relevant to substances such as high molecular weight dextrans and proteins. In general, molecules less than 30 Angstroms are freely filtered at the glomerulus. For drugs that are filtered, it is predictable that decreases in overall renal function, as reflected by a decreased GFR, will result in drug accumulation and may require dose adjustment in patients with renal disease. For drugs that are actively secreted, glomerular filtration rate is less important than renal plasma flow. For some drugs, their avidity for the transport pump is sufficiently greater than the binding affinity to circulating proteins that the drug is effectively ‘stripped’ from the protein and secreted into the urine. As such, they can achieve renal clearance rates that approach renal blood flow, i.e. in the limit all the drug presented to the kidney can be removed from the perfusing blood and secreted into the urine.

Drugs that are actively secreted will also accumulate in patients with decreased renal function, because renal blood flow and GFR usually decrease in parallel. However, in addition, these drugs are subject to competition for transport. Thus, there is concern with clinical situations in which concomitant drugs might be administered that could inhibit transport, thereby exposing the patient to increased circulating drug concentrations.

The tubular reabsorption of drugs follows the principles of passive nonionic diffusion and is dependent upon urinary pH and the pKa of the drug. A urine pH that favours the nonionized state of the drug enhances its lipophilicity and increases its passive reabsorption across the tubular membrane. For drugs that are subject to reabsorption, the extent of this process is also dependent on urinary volume. The clinical implications of kidney tubular reabsortion relate mostly to the effect of disease on the process. Normally, the urinary pH is acidic. Thus the considerations for drug reabsorption occur mainly where there are alterations in urinary pH such as in syndromes of renal tubular acidosis or during administration of acids or bases for other clinical indications.

Glomerular filtration

As noted previously, the overall elimination of many drugs has an important component that is dependent upon renal function [25]. Among the different pathways of renal elimination, glomerular filtration is the most important in terms of the numbers of drugs that are affected. Compendia are published periodically that enumerate these drugs and offer recommendations as to the need for adjusting doses in patients with renal insufficiency (e.g [25]). From a drug development perspective, it is critically important in the earliest phase of development to determine whether or not renal function is an important component of elimination.

As noted previously, excretion of 30% or more of a parent drug or active metabolite in the urine warrants consideration of dose adjustment in patients with renal insufficiency and/or admonitions against using the drug in such patients. Even if a drug achieves this level of excretion in the urine via active secretion, the implications are the same in terms of the potential need for dose adjustment in patients with renal insufficiency because renal blood flow and GFR change in parallel. If early phases of drug development show that renal elimination is important, further studies need to be performed to discern whether there is an active secretory component to elimination. Such studies require the use of markers of GFR, comparing true glomerular filtration rate to renal clearance of the unbound drug. If the latter exceeds GFR, then secretion is a component of elimination in addition to filtration. Accordingly additional studies need to be conducted to evaluate the secretory pathway and the potential for drug interactions. If secretion is not a component of renal elimination, studies are indicated to assess the relationship between total clearance of the drug of interest and GFR. These will allow recommendations for dose adjustment in future trials and/or clinical use. In addition, it is possible to identify groups of patients in whom use of the drug should be avoided altogether.

Active secretion

Transport pumps responsible for the active secretion of drugs from blood to urine have been identified for organic acids [26–30], organic bases [31–37], nucleosides [38], and p-glycoprotein (PGP) is also involved [39–45]. Each of these transport systems have been reasonably well characterized as have substrates for them. Transporters in a variety of species have been cloned, but considerable research still remains to define their structure-activity characteristics. Each of these systems is capable of transporting a variety of substrates, and there is potential for competition for transport. Thus, organic acids can compete with other organic acids, bases with bases, etc. A classic example refers to probenecid a prototypic inhibitor of the organic acid pathway. This compound decreases markedly the renal secretion of other organic acids, such as penicillins, thiazide and loop diuretics. The organic base transporters are less well characterized. Substrates include procainamide, histamine H2-antagonists and trimethoprim. Again competition for transport between substrates is possible. Transport of nucleocides is even less well characterized. Theoretically, substrates for this pathway could compete with one another, but this possibility is poorly defined in humans.

Substantial interest has focussed on PGP over the past few years [39–45]. This transporter was first identified in tumours resistant to chemotherapeutic agents. Upregulation of PGP and related transporters is responsible for this resistance by pumping chemotherapeutic agents out of the cell. PGP is also present in the blood–brain barrier, the intestinal mucosa, and the kidney. Many studies have now demonstrated that PGP is able to secrete a variety of substrates into the urine [39–45]. The classic substrate for PGP in the kidney is digoxin. Other substrates/inhibitors include verapamil and cyclosporin.

As noted above, if the unbound renal clearance of a drug exceeds that of a marker for GFR (e.g. iothalamate), then active secretion is occurring. From the chemistry of the compound, it may be possible to predict which transporter(s) might be involved. Such predictions can guide in vitro and in vivo studies aimed at defining the role of such transporters and identifying other compounds that inhibit renal excretion. PGP, for example, can be expressed in a colon cancer cell line, and this tissue can be used in vitro to assess whether or not a drug is a substrate. Inhibitors can also be tested in such tissue models. Depending upon the in vitro findings, appropriate in vivo studies should be performed to confirm interactions and their extent. Such information can then be used for labelling and for precautions or exclusions during efficacy trials.

Passive nonionic tubular reabsorption

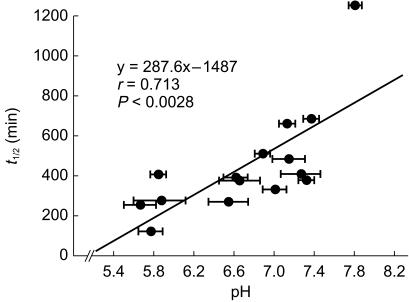

Drugs that are excreted into the kidney tubular fluid are also subject to reabsorption at the distal nephron. This process follows the principles of passive nonionic diffusion, such that the nonionized form of a drug is more lipid soluble and can be reabsorbed [46–48]. The degree of reabsorption may vary considerably with urinary pH. For acidic drugs, an acidic urine results in an increased concentration of nonionized drug, thereby optimizing the extent of reabsorption. In contrast, an alkaline urine increases the degree of ionization, thereby enhancing renal excretion. This is the rationale for the use of an alkaline diuresis in treating salicylate overdoses. For basic drugs such as pseudoephridine, the reverse is true such that an alkaline urine favours the nonionized species, enhancing reabsorption and decreasing overall drug elimination (Figure 4) [20].

Figure 4.

Effect of urinary pH on the elimination half-life of pseudoephedrine. Since pseudoephridine is a weak base, as urine pH becomes more alkaline, the concentration of nonionized drug in tubular fluid increases and is subject to reabsorption. This decreases renal elimination and prolongs the half-life (from reference 20 with permission).

If, during drug development, it is found that the compound undergoes substantial tubular reabsorption, further studies can be conducted to determine whether or not urinary pH has an important impact on its overall elimination. However, in deciding whether to pursue such studies, it is necessary to realize that urinary pH is normally acidic. There are only a few pathologic conditions where urine pH is persistently alkaline. These include syndromes of renal tubular acidosis and where patients are administered high doses of antacids. If the drug under development might be used in such conditions, then it is important to pursue studies of urine pH dependence.

For drugs that show urine pH dependent elimination, urine volume can also influence the total amount of drug that is excreted [46–48]. Since extremes of urinary volume usually only occur in patients with diseases such as diabetes insipidus, this consideration is rarely of clinical importance.

Conclusions

There are many ways in which an appreciation of renal function impinges on drug development. Thus, it is important to be familiar with methods for the accurate determination of renal function and of the ways in which the kidney contributes to drug disposition. A thorough understanding of these factors at the earliest stages of drug development will allow better selection of doses for subsequent clinical trials, better selection of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and more accurate labelling once a drug is approved.

References

- 1.Zaltzman JS, Whiteside C, Cattran DC, Lopez FM, Logan AG. Accurate measurement of impaired glomerular filtration using single-dose oral cimetidine. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:504–511. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roubenoff R, Drew H, Moyer M, Petri M, Whiting-O'Keefe Q, Hellmann DB. Oral cimetidine improves the accuracy and precision of creatinine clearance in lupus nephritis. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:501–506. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-7-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi C, Donadio C, Tramonti G. Noninvasive methods for the measurement of total renal function. Nephron. 1981;28:53–57. doi: 10.1159/000182104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS. Measurement of renal function in chronic renal disease. Kidney Int. 1990;38:167–184. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shemesh O, Golbetz H, Kriss JP, Myers BD. Limitations of creatinine as a filtration marker in glomerulopathic patients. Kidney Int. 1985;28:830–838. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walser M, Drew H, LaFrance ND. Creatinine measurements often yield false estimates of progression in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1988;34:412–418. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dossetor JB. Creatininemia versus uremia. The relative significance of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine concentrations in azotemia. Ann Intern Med. 1966;65:1287–1299. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-65-6-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elwood CM, Sigman EM. The measurement of glomerular filtration rate and effective renal plasma flow in man by iothalamate 125I and iodopyracet 131I. Circulation. 1967;36:441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.36.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maher FT, Nolan NG, Elveback LR. Comparison of simultaneous clearances of 125I-labeled sodium iothalamate (Glofil) and of inulin. Mayo Clin Proc. 1971;46:690–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalmeida W, Suki WN. Measurement of GFR with non-radioisotopic radio contrast agents. Kidney Int. 1988;34:725–728. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choyke PL, Austin HA, Frank JA, et al. Hydrated clearance of gadolinium-DTPA as a measurement of glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 1992;41:1595–1158. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea PH, Maher JF, Horak E. Prediction of glomerular filtration rate by serum creatinine and β2-microglobulin. Nephron. 1981;29:30–35. doi: 10.1159/000182234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahira R, Yonemura K, Yonekawa O, et al. Tryptophan glycoconjugate as a novel marker of renal function. Am J Med. 2001;110:192–197. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maïza A, Waldek S, Ballardie FW, Daley-Yates PT. Estimation of renal tubular secretion in man, in health and disease, using endogenous N-1-methylnicotinamide. Nephron. 1992;60:12–16. doi: 10.1159/000186698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannedouche T, Laude D, Déchaux M, Grünfeld J-P, Elghozi J-L. Plasma 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid as an endogenous index of renal plasma flow. Kidney Int. 1989;35:95–98. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brater DC, Sokol PP, Hall SD, McKinney TD. Renal elimination of drugs: methods and determinants. In: Seldin DW, Giebisch G, editors. The Kidney. Physiology and pathophysiology. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 3597–3628. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker GT. Measurement of the renal clearance of drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;12:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keeler R. The effects of ‘dead space’ and urine flow changes on measurements of glomerular filtration rate by clearance methods. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:435–438. doi: 10.1139/y83-066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brater DC. Renal disorders and the influence of renal function on drug disposition. In: Carruthers SG, Hoffman BB, Melmon KL, Nierenberg DW, editors. Melmon and Morrelli's Clinical Pharmacology. 4. McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 363–400. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brater DC, Kaojarern S, Benet LZ, et al. Renal excretion of pseudoephedrine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;28:690–694. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1980.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferry N, Bernard N, Pozet N, et al. The influence of renal insufficiency and haemodialysis on the kinetics of ciprofibrate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:675–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallustio BC, Purdie YJ, Birkett DJ, Meffin PJ. Effect of renal dysfunction on the individual components of the acyl-glucuronide futile cycle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faed EM. Properties of acyl glucuronides: implications for studies of the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of acidic drugs. Drug Metab Rev. 1984;15:1213–1249. doi: 10.3109/03602538409033562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grubb NG, Rudy DW, Brater DC, Hall SD. Stereoselective phramacokinetics of ketoprofen and ketoprofen glucuronide in end-stage renal disease: evidence for a futile cycle of elimination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:494–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brater DC, Hall SD. Disposition and dose requirements of drugs in renal insufficiency. In: Seldin DW, Giebisch G Lippincott, editors. The Kidney. Physiology and Pathophysiology. 3. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 2923–2942. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burckhardt G, Ullrich KJ. Organic anion transport across the contraluminal membrane – dependence on sodium. Kidney Int. 1989;36:370–377. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masereeuw R, Russel FGM, Miller DS. Multiple pathways of organic anion secretion in renal proximal tubule revealed by confocal microscopy. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F1173–F1182. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.6.F1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu R, Chan BS, Schuster VL. Cloning of the human kidney PAH transporter: narrow substrate specificity and regulation by protein kinase C. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F295–F303. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.2.F295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosoyamada M, Sekine T, Kanai Y, Endou H. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a multispecific organic anion transporter from human kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F122–F128. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.1.F122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Aubel RAMH, Masereeuw R, Russel FGM. Molecular pharmacology of renal organic anion transporters. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:F216–F232. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosoglou T, Rocci ML, Vlasses PH. Trimethoprim alters the disposition of procainamide and N-acetylprocainamide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44:467–477. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gründemann D, Gorboulev V, Gambaryan S, Veyhl M, Koepsell H. Drug excretion mediated by a new prototype of polyspecific transporter. Nature. 1994;372:549–552. doi: 10.1038/372549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pietruck F, Ullrich KJ. Transport interactions of different organic cations during their excretion by the intact rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1647–1657. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKinney TD, Speeg KV. Cimetidine and procainamide secretion by proximal tubules in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:F672–F680. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.242.6.F672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rennick BR. Renal tubule transport of organic cations. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:F83–F89. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.240.2.F83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Notterman DA, Drayer DE, Metakis L, Reidenberg MM. Stereoselective renal tubular secretion of quinidine and quinine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. :511–517. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyamoto Y, Tiruppathi C, Ganapathy V, Leibach FH. Multiple transport systems for organic cations in renal brush-border membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:F540–F548. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.4.F540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brett CM, Washington CB, Ott RJ, Gutierrez MM, Giacomini KM. Interaction of nucleoside analogues with the sodium-nucleoside transport system in brush border membrane vesicles from human kidney. Pharm Res. 1993;10:423–426. doi: 10.1023/a:1018948608211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuruoka S, Sugimoto K-I, Fujimura A, Imai M, Asano Y, Muto S. P-glycoprotein-mediated drug secretion in mouse proximal tubule perfused in vitro. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:177–181. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V121177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschraagen M, Koks CHW, Schellens JHM, Beijnen JH. P-glycoprotein system as a determinant of drug interactions: the case of digoxin-verapamil. Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:301–306. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakasugi H, Yano I, Ito T, et al. Effect of clarithromycin on renal excretion of digoxin: interaction with P-glycoprotein. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:123–128. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hori R, Okamura N, Aiba T, Tanigawara Y. Role of P-glycoprotein in renal tubular secretion of digoxin in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:1620–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okamura N, Hirai M, Tanigawara Y, et al. Digoxin–cyclosporin A interaction. modulation of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein in the kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:1614–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ernest S, Bello-Reuss E. P-glycoprotein functions and substrates: possible roles of MDR1 gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 1998;53:S11–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dutt A, Heath LA, Nelson JA. P-glycoprotein and organic cation secretion by the mammalian kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:1254–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner IM, Mudge GH. Renal tubular mechanisms for excretion of organic acids and bases. Am J Med. 1964;36:743–762. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scribner BH, Crawford MA, Dempster WJ. Urinary excretion by nonionic diffusion. Am J Physiol. 1959;196:1135–1140. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milne MD, Scribner BH, Crawford MA. Non-ionic diffusion and the excretion of weak acids and bases. Am J Med. 1958;24:709–729. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(58)90376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]