Abstract

Sister-chromatid separation in mitosis requires proteolytic cleavage of a cohesin subunit. Separase, the corresponding protease, is activated at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. Activation involves proteolysis of an inhibitory subunit, securin, following ubiquitination mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome. In Drosophila, the securin PIM associates not only with separase (SSE), but also with an additional protein, THR. Here we show that THR is cleaved after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. THR cleavage only occurs in functional SSE complexes and in a region that matches the separase cleavage-site consensus. Mutations in this region abolish mitotic THR cleavage. These results indicate that THR is cleaved by SSE. Expression of noncleavable THR variants results in cold-sensitive maternal-effect lethality. This lethality can be suppressed by a reduction of catalytically active SSE levels, indicating that THR cleavage inactivates SSE complexes. THR cleavage is particularly important during the process of cellularization, which follows completion of the last syncytial mitosis of early embryogenesis, suggesting that Drosophila separase has other targets in addition to cohesin subunits.

Keywords: Mitosis, sister-chromatid separation, securin, separase, pimples, three rows

Separase is a eukaryotic endopeptidase that resolves the cohesion between sister chromatids by cleaving the Scc1/Mcd1/Rad21 subunit of the cohesin complex (Uhlmann et al. 1999, 2000). Scc1 should be cleaved neither during S phase, when sister-chromatid cohesion needs to be established, nor during G2 phase and early mitosis, when cohesion is required for the correct bipolar orientation of sister chromatids within the mitotic spindle. However, at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition cohesion must be resolved efficiently and completely to allow faithful segregation of sister chromatids to daughter cells. Separase activity, therefore, is subject to careful regulation. Although separase has been shown to be required for sister-chromatid separation in a wide range of eukaryotes (Funabiki et al. 1996a; Ciosk et al. 1998; Zou et al. 1999; Jäger et al. 2001; Siomos et al. 2001), its regulation is poorly understood and appears to be surprisingly divergent in different organisms.

Regulatory subunits that associate with separase have been identified in diverse species (budding yeast Pds1, fission yeast Cut2, Drosophila PIM, vertebrate PTTG; Funabiki et al. 1996a; Ciosk et al. 1998; Zou et al. 1999; Jäger et al. 2001). These securin proteins share almost no sequence similarity and appear to have different additional roles beyond a shared inhibitory function. Separase inhibition by securins is canceled at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition by ubiquitin-dependent degradation (Ciosk et al. 1998). Securin ubiquitination is mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), which, in turn, is regulated by the mitotic spindle checkpoint (for review, see Shah and Cleveland 2000). The mitotic securin degradation, therefore, is only initiated when all chromosomes have reached the correct bipolar orientation within a functional mitotic spindle.

Securins not only function as separase inhibitors, they also act as positive regulators of separase function. Therefore, the securins of fission yeast and Drosophila are absolutely required for sister-chromatid separation during mitosis (Funabiki et al. 1996b; Stratmann and Lehner 1996). In contrast, the securins of budding yeast and vertebrates are not essential (Yamamoto et al. 1996; Jallepalli et al. 2001; Mei et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2001). However, the mild consequences of securin gene inactivation in vertebrates might be explained by the presence of redundant securins, as two additional highly similar PTTG genes have been identified in the human genome sequence (Chen et al. 2000).

Separase is also regulated by securin-independent mechanisms. A recent study revealed that vertebrate separase activity is inhibited by Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation (Stemmann et al. 2001). In addition, activation of human but not of yeast separase is accompanied by self-cleavage (Waizenegger et al. 2000; Stemmann et al. 2001). Although self-cleavage clearly does not result in complete inactivation (Stemmann et al. 2001), it is not yet known whether this autoprocessing is causally involved in human separase activation.

The apparent mechanistic diversity of separase regulation in different organisms is paralleled by a lack of primary sequence similarity among not only the securins but also the N-terminal separase domains. These N-terminal regions encompass more than 110 kD in all separases except the Drosophila separase homolog SSE. SSE is an exceptionally small separase family member, which consists almost entirely of the conserved cysteine endoprotease domain (Jäger et al. 2001). However, SSE associates not only with the securin Pimples (PIM), but also with the Three rows protein (THR), which does not appear to have orthologs outside Drosophila (Jäger et al. 2001). We have speculated, therefore, that thr might encode an N-terminal separase domain, which was separated by a gene split from an ancient separase gene during Drosophila evolution (Jäger et al. 2001). Consistent with this proposal, PIM binds to THR (Leismann et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2001), whereas securins bind to the N-terminal domains of separases in yeast (Kumada et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2001). Like SSE and PIM, THR is also absolutely required for sister-chromatid separation (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Philp et al. 1993).

To clarify SSE regulation, we have analyzed the role of THR in further detail. Interestingly, we find that THR is cleaved after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, apparently by the associated SSE. Moreover, our analysis of cleavage-resistant mutations suggests that THR cleavage is most important for separase inhibition during early embryogenesis of Drosophila.

Results

THR is proteolytically cleaved during mitosis

To analyze the intracellular distribution of THR during the cell cycle, we immunolabeled Drosophila embryos with antibodies against THR. In addition, we studied the behavior of a myc-epitope-tagged THR protein expressed from a transgene under control of the thr regulatory region. This gthr–myc transgene rescues thr null mutants completely (Leismann et al. 2000). THR–myc (Fig. 1C,F) as well as THR (data not shown) were found to be cytoplasmic during interphase and distributed throughout the cell during early mitosis. This intracellular distribution is therefore identical to that previously described for the securin PIM, which is known to form a complex with THR and SSE (Stratmann and Lehner 1996; Leismann et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2001).

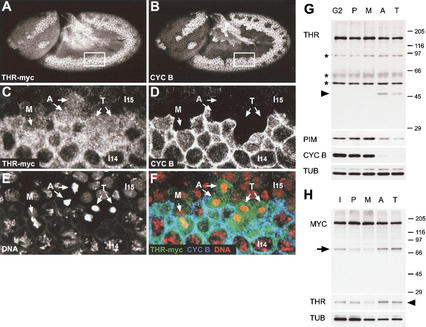

Figure 1.

THR is degraded during mitosis. Embryos (A,B) expressing gthr–myc were fixed at the stage of mitosis 14 and labeled with antibodies against the myc epitope (A,C,F), cyclin B (B,D,F), and a DNA stain (E,F). The boxed area in A and B is shown in C–F. Red, green, and blue in the merged panel F represent DNA, anti-myc, and anti-cyclin B labeling, respectively. M, metaphase; A, anaphase; T, telophase; I14, interphase 14; I15, interphase 15. (G) Synchronous progression through mitosis 14 was induced, and extracts were prepared from embryos with all cells in G2 before mitosis 14 (G2), as well as in prophase (P), metaphase (M), anaphase (A), and telophase (T) of mitosis 14. Extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against THR (THR), PIM (PIM), cyclin B (CYC B), and tubulin (TUB). A 47-kD fragment appearing after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is indicated by an arrowhead. Asterisks indicate cross-reacting bands. (H) Extracts from gthr–myc embryos during interphase (I), prophase (P), metaphase (M), anaphase (A), and telophase (T) of the synchronous syncytial blastoderm cycles were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against the myc epitope (MYC), THR (THR), and tubulin (TUB). Mitotic cleavage products of THR–myc and endogenous THR are indicated by an arrow and an arrowhead, respectively.

Interestingly, THR and THR–myc signals were observed to decline during exit from mitosis. This decline was most clearly detected during mitosis 14 in embryos with only maternal and no zygotic gthr–myc expression (Fig. 1A–F). Maternal thr transcripts are rapidly degraded during interphase 14 (D'Andrea et al. 1993). As a consequence, maternally derived THR protein can no longer be synthesized after mitosis 14. The disappearance of the maternally derived THR–myc protein during exit from mitosis 14, therefore, is not concealed by THR–myc reaccumulation in embryos that cannot express gthr–myc zygotically. Mitosis 14 occurs in a highly reproducible pattern (Foe 1989), which is readily revealed by immunolabeling with antibodies against cyclin B. Anti-cyclin B immunolabeling is absent from cells that have just completed mitosis, but is present in the cytoplasm of cells that have not yet progressed through mitosis (Fig. 1B). Double labeling showed that the distribution of THR–myc was almost indistinguishable from that of cyclin B (Fig. 1, cf. A and B), clearly indicating that the decline of THR–myc is coupled to progression through mitosis. However, careful comparisons indicated that cyclin B is degraded more rapidly and completely than THR–myc (Fig. 1C–F).

To confirm mitotic THR degradation by immunoblotting, we induced a synchronous progression through mitosis 14 (see Materials and Methods). As expected, cyclin B was readily detected up to metaphase and essentially absent in anaphase and telophase (Fig. 1G). PIM degradation was found to be less rapid and complete than cyclin B destruction (Fig. 1G). Immunoblotting with antibodies against THR indicated that the disappearance of full-length THR was also limited (Fig. 1G). However, a distinct 47-kD band was observed exclusively in anaphase and telophase extracts (Fig. 1G, see arrowhead), indicating that a fraction of THR is proteolytically cleaved after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition.

Because our antibodies detected proteins other than THR in the extracts, it was important to confirm that the 47-kD band observed after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition was derived from THR. Therefore, we analyzed gthr–myc embryo extracts with antibodies against myc (Fig. 1H). To prepare these extracts, we pooled embryos at distinct stages of the synchronous syncytial mitoses before cellularization. Similarly as in the mitosis 14 extracts (Fig. 1G), a THR fragment that strongly increased in intensity after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition was specifically detected by anti-myc (Fig. 1H, see arrow). Taking the C-terminal myc tags into account, this 70-kD fragment appeared to indicate the same proteolytic event as the 47-kD fragment observed by our antibodies against a C-terminal THR domain (Fig. 1G). Moreover, reprobing the blot of the syncytial gthr–myc extracts with these latter antibodies revealed the 47-kD THR fragment with intensities that closely paralleled those of the 70-kD THR–myc fragment (Fig. 1H, see arrowhead).

THR and THR–myc cleavage fragments were also observed in phases other than anaphase and telophase (Fig. 1H), but only during the syncytial cycles. The cleavage products are therefore presumably not completely degraded during the extremely brief syncytial interphases of only a few minutes. The instability of these C-terminal cleavage fragments, however, explains the decline of THR signals during exit from mitosis 14 observed by immunofluorescence, as our antibodies recognize C-terminal epitopes. We have no information concerning the stability and intracellular distribution of the N-terminal THR part, because our antibodies do not recognize the THR N terminus and because N-terminal epitope tags were found to abolish THR function (data not shown).

A separase cleavage consensus motif is required for mitotic THR cleavage

To assess the regulatory significance of THR cleavage, we mapped and mutated the cleavage site. Based on the size of the mitotic THR and THR–myc fragments, the mitotic cleavage was predicted to occur approximately between amino acids 930 and 1030. C-terminal THR fragments starting at different positions within this region were generated by in vitro translation, and their electrophoretic mobility was compared with the mobility of the fragment generated during mitosis in vivo (Fig. 2A). The mitotic in vivo cleavage fragment comigrated with the smallest in vitro fragment starting at position 1032. Interestingly, the region surrounding this position (1031–VEPIRKQ–1037) displays significant similarity to the separase cleavage-site consensus derived from various mitotically and meiotically cleaved cohesin subunits (Fig. 2B; Hauf et al. 2001). Moreover, comparison of THR proteins from D. melanogaster, Drosophila pseudoobscura, and Drosophila virilis revealed that the VEPIRKQ motif is invariant (H. Jäger, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.). We point out that THR is a fast-evolving protein and apart from this potential cleavage region, there is only one other region with more extensive conservation.

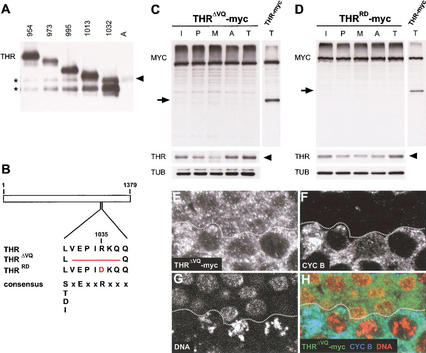

Figure 2.

Mapping the mitotic THR cleavage site. (A) C-terminal THR fragments were generated in vitro and resolved next to an anaphase embryo extract (lane A, same extract as in Fig. 1G, lane A). THR fragments were detected by immunoblotting with anti-THR antibodies. The numbers above the lanes indicate the amino acid position at which the C-terminal THR fragments start. The arrowhead indicates the C-terminal THR fragment generated in vivo after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. Asterisks indicate partial products of the THR fragments generated in vitro. (B) Schematic illustration of the mitotic cleavage region within THR, THRΔVQ, and THRRD. In addition, the separase cleavage-site consensus sequence (Hauf et al. 2001) is shown below the THR sequences. Cleavage by separase occurs C-terminal from the conserved arginine residue. (C,D) Extracts from gthrΔVQ–myc (C) or gthrRD–myc (D) embryos during interphase (I), prophase (P), metaphase (M), anaphase (A), and telophase (T) of the synchronous syncytial blastoderm cycles were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against the myc epitope (MYC), THR (THR), and tubulin (TUB). In addition, a telophase extract from gthr–myc embryos was analyzed in parallel (right lanes). Mitotic cleavage products of THR–myc and endogenous THR are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. (E–H) Embryos expressing gthrΔVQ–myc were fixed at the stage of mitosis 14 and labeled with antibodies against the myc epitope (E), cyclin B (F), and a DNA stain (G). Red, green, and blue in the merged image (H) represent labeling of DNA, myc, and cyclin B, respectively. The epidermal region shown corresponds to the boxed region in Figure 1A. Cells below the dotted line are in G2 before mitosis 14, whereas cells above the dotted line have progressed through mitosis 14 and are mostly in early interphase of cycle 15. Note that THRΔVQ–myc is still present at high levels in these cells, in contrast to THR–myc (see Fig. 1C–F).

To test whether the conserved separase cleavage-site consensus region is, indeed, important for cleavage, we generated mutants (Fig. 2B). In the first mutant, we deleted the separase cleavage-site consensus (THRΔVQ, deletion of amino acids 1031–VEPIRKQ–1037). In the second mutant, the arginine residue at position 1035 was exchanged for an aspartate (THRRD). The identical mutation in the separase cleavage sites of Scc1 has been shown to abolish cleavage in yeast (Uhlmann et al. 1999), and similar mutations (arginine to alanine) rendered human Scc1 resistant to separase cleavage (Hauf et al. 2001). We established transgenic lines expressing myc-epitope-tagged variants of these two THR mutants and analyzed their cleavage. Both mutant proteins were completely refractory to mitotic cleavage, whereas endogenous THR was still cleaved (Fig. 2C,D). Immunofluorescence analysis during mitosis 14 indicated that the cleavage-resistant mutants THRΔVQ–myc and THRRD–myc were not degraded during exit from mitosis (Fig. 2E–H; data not shown). We conclude that the separase cleavage-site consensus region in THR is required for mitotic THR cleavage and that this cleavage causes the decline of THR during exit from mitosis.

Mitotic THR cleavage requires functional SSE complexes

If SSE is the protease responsible for THR cleavage, then THR should be stable in cells arrested by the mitotic spindle checkpoint. Immunofluorescence analysis of gthr–myc embryos permeabilized and treated with the microtubule inhibitor demecolcine showed that THR–myc is, indeed, stabilized in checkpoint-arrested cells. These cells were identified by double labeling with antibodies against cyclin A (Fig. 3C) and a DNA stain (Fig. 3E). Cyclin A is known to be degraded in arrested cells, which are also characterized by condensed chromosomes (Whitfield et al. 1990). All arrested cells were found to contain high THR–myc levels (Fig. 3A), whereas, as expected, THR–myc levels were very low in cells of mock-treated embryos that had completed mitosis 14 (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, immunoblot analysis of demecolcine-treated syncytial embryos clearly showed a drastic reduction in the abundance of the THR–myc cleavage product (Fig. 3G).

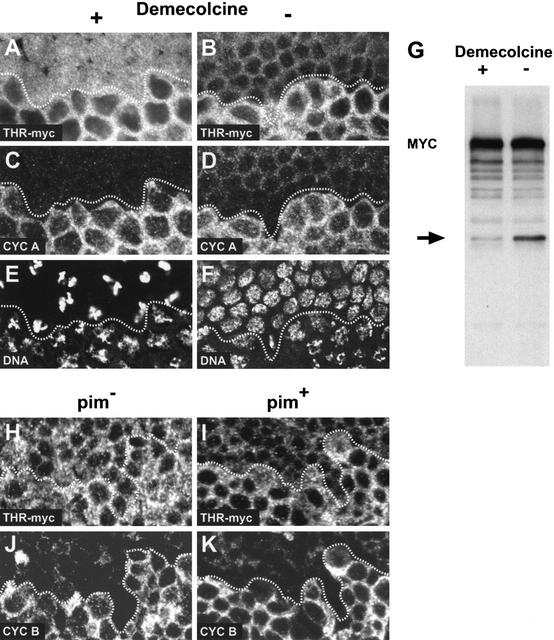

Figure 3.

THR cleavage is inhibited in cells arrested by the mitotic spindle checkpoint and in pim mutants. (A–F) Embryos expressing gthr–myc were permeabilized and incubated in the presence (A,C,E) or absence (B,D,F) of the microtubule inhibitor demecolcine while progressing through mitosis 14. After fixation, embryos were labeled with antibodies against the myc epitope (A,B), cyclin A (C,D), and a DNA stain (E,F). Comparable epidermal regions are shown. Cells below the dotted line are in G2 before mitosis 14, whereas cells above the dotted line have progressed into mitosis 14 and are arrested with condensed chromatin (E) or are already in early interphase of cycle 15 (F). THR–myc is present at high levels in arrested cells (A), and only at low levels in interphase 15 cells (B). (G) gthr–myc embryos during the syncytial blastoderm cycles were permeabilized and incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of demecolcine. Embryo extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-myc. The THR–myc fragment appearing after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is indicated by an arrow. (H–K) pim− embryos (H,J) and pim+ sibling embryos (I,K) expressing gthr–myc were fixed at the stage of mitosis 15 and labeled with antibodies against the myc epitope (H,I) and cyclin B (J,K). In the epidermal region shown, cells below the dotted line are in G2 before mitosis 15, whereas cells above the dotted line have progressed through mitosis 15 and are mostly in early interphase of cycle 16. These latter cells have high levels of THR–myc in pim− embryos (H), and only low levels in pim+ sibling embryos (I).

Phenotypic analyses of various mutants provided additional evidence supporting the suggestion that THR is cleaved by SSE. Cytologically, the mutant phenotypes resulting from the loss of thr, Sse, or pim function have been shown to be identical (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Philp et al. 1993; Stratmann and Lehner 1996; Jäger et al. 2001). Sister-chromatid separation fails in all three mutants. Moreover, we have previously shown that THR, PIM, and SSE form a trimeric complex (Jäger et al. 2001), which appears to be a prerequisite for activation of separase activity at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. Accordingly, pim mutants presumably lack separase activity. Therefore, we analyzed THR–myc stability during exit from mitosis in pim mutant embryos. Mitosis 15 is the first division that is affected in pim mutant embryos, but the previous mitoses proceed normally because of a maternally provided pim+ contribution (Stratmann and Lehner 1996). We observed that THR–myc is no longer degraded during mitosis 15 in pim mutant embryos (Fig. 3H), whereas it declined normally in pim+ sibling embryos as expected (Fig. 3I).

Additional evidence for the role of SSE in THR cleavage was obtained with transgenes encoding different THR deletion mutants. We have previously shown that a mutant (THR 445–1379–myc) lacking the N-terminal PIM-binding site can still associate with SSE (Jäger et al. 2001). However, this mutant is unable to rescue mutations in the endogenous thr gene (data not shown). As this mutant still contains the normal C-terminal region with the cleavage site, we analyzed its cleavage. Analysis in syncytial embryos indicated that THR 445–1379–myc is not cleaved (Fig. 4A). Moreover, THR 445–1379–myc was also not degraded during mitosis 14 (Fig. 4C). We point out that THR 445–1379–myc was expressed in a thr+ background in these experiments. Thus, despite the presence of functional and active SSE complexes in this background, THR 445–1379–myc that still binds to SSE was not cleaved during mitosis. A C-terminal deletion mutant (THR 1–1204–myc) is also unable to provide thr+ function, even though this mutant can bind to both PIM and SSE to a degree comparable with full-length THR 1–1379–myc (data not shown). The analysis of THR 1–1204–myc, which also still contains the cleavage region, revealed that its cleavage in syncytial embryos is greatly reduced (Fig. 4B) and that the protein is stabilized in mitosis 14 (Fig. 4D).

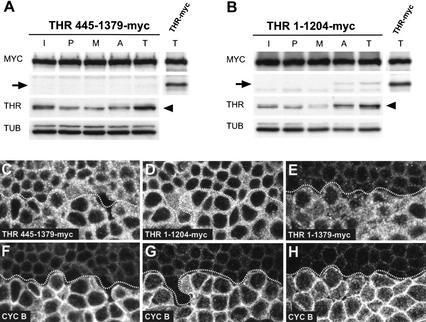

Figure 4.

THR cleavage occurs only within functional SSE complexes. (A,B) Extracts from gthr 445–1379–myc (A) or gthr 1–1204–myc (B) embryos during interphase (I), prophase (P), metaphase (M), anaphase (A), and telophase (T) of the synchronous syncytial blastoderm cycles were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against the myc epitope (MYC), THR (THR), and tubulin (TUB). In addition, a telophase extract from gthr–myc embryos was analyzed in parallel (right lanes). The proteins THR 445–1379–myc, THR 1–1204–myc, and THR–myc all contain the cleavage region and associate with SSE. Mitotic cleavage products of THR–myc and endogenous THR are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. (C–H) Embryos expressing gthr 445–1379–myc (C,F), gthr 1–1204–myc (D,G), or gthr–myc (E,H) were fixed at the stage of mitosis 14 and labeled with antibodies against the myc epitope (C–E) and cyclin B (F–H). Comparable epidermal regions are shown. Cells below the dotted lines are in G2 before mitosis 14, whereas cells above the dotted lines have progressed through mitosis 14 and are in early interphase of cycle 15. Note that THR 445–1379–myc (C) and THR 1–1204–myc (D) are still present at high levels in these cells, in contrast to THR–myc (E).

We conclude that our findings in checkpoint-arrested cells, in pim mutants, and with the different thr deletion mutants all strongly support the argument that THR cleavage can only proceed within complexes that contain active SSE.

Expression of noncleavable THR results in a cellularization defect

To address the physiological significance of mitotic THR cleavage, we characterized the phenotype associated with the mutations abolishing cleavage. The transgenes gthrΔVQ–myc and gthrRD–myc include the wild-type thr regulatory region. By crossing these transgenes into a thr null mutant background, we analyzed whether the noncleavable THR proteins can functionally replace wild-type THR. The gthrΔVQ–myc and gthrRD–myc transgenes complemented the embryonic lethality associated with null mutations in the endogenous thr gene and supported development to the adult stage. The rescued flies hatched with the expected frequency and displayed no apparent morphological defects. Thus, the noncleavable THR variants must be at least partially functional.

However, the gthrΔVQ–myc and gthrRD–myc transgenes resulted in cold-sensitive female sterility. Females with two transgene copies in a wild-type background were almost completely sterile at 18°C, whereas at 25°C they were fertile. Even at 18°C, plenty of eggs were laid. However, very few larvae were observed to hatch from these eggs. This maternal-effect lethality at 18°C was observed with females homozygous for either single gthrΔVQ–myc or gthrRD–myc insertions, and also with females heterozygous for one of six different chromosomes carrying recombined pairs of independent gthrΔVQ–myc insertions, ruling out position effects of transgene insertions (Fig. 5A, 6A, below; data not shown). Moreover, the maternal-effect lethality was not observed with females carrying two copies of gthr–myc (Fig. 5A), showing that this phenotype does not result from an increased thr+ gene dose. However, the dose of gthrΔVQ–myc or gthrRD–myc was found to be critical. Maternal-effect lethality was not observed with females carrying only one transgene copy (Fig. 5A).

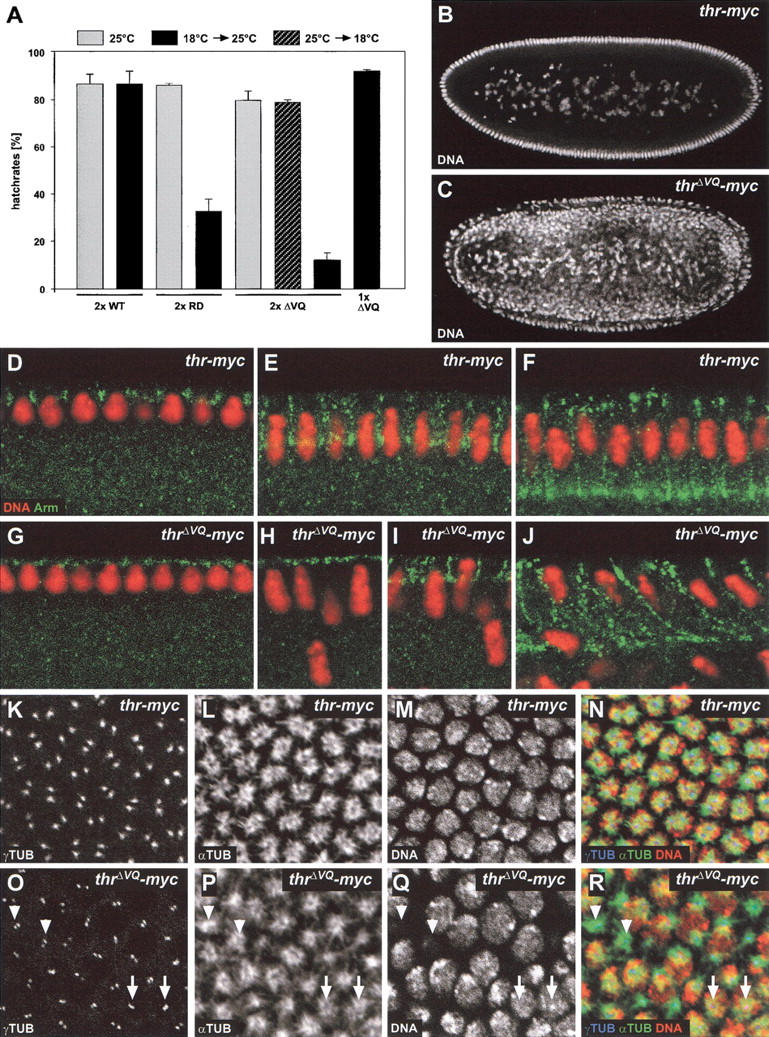

Figure 5.

Phenotype associated with expression of noncleavable THR. (A) Noncleavable THR present during early embryonic development causes cold-sensitive, maternal-effect lethality. Eggs were collected at 25°C for 1 h from females homozygous for the transgene insertions gthr–myc (2× WT), gthrRD–myc (2× RD), or gthrΔVQ–myc (2× ΔVQ), or heterozygous for gthrΔVQ–myc (1× ΔVQ). Eggs were incubated at 25°C (gray bars); or shifted to 18°C after 3.5 h (hatched bar); or shifted to 18°C for 4.5 h, followed by a shift back to 25°C (black bars). The larval hatch rates (% of hatched eggs) are given as average values obtained from three independent experiments. (B,C) Noncleavable THR causes internalization of nuclei during early embryonic development. Embryos derived from females homozygous for gthr–myc (B) or gthrΔVQ–myc (C) were incubated during their early development at 18°C, fixed, and stained for DNA. (D–J) Cellularization is delayed in THRΔVQ embryos. Cellularizing THR (D–F) and THRΔVQ (G–J) embryos were fixed and labeled with an antibody against Armadillo (Arm, green) and a DNA stain (DNA, red). (K–R) Noncleavable THR affects centrosome separation. THR (K–N) or THRΔVQ (O–R) embryos were fixed during cellularization at 18°C, stained for DNA, and labeled with antibodies against γ-tubulin (γTUB) and α-tubulin (αTUB). Apical confocal sections that contained the γTUB signals were stacked (K,L,O,P), and a lower section was taken for DNA (M,Q). Arrows indicate unseparated centrosomes. Arrowheads denote positions where nuclei had dropped into the interior of the embryo and had left behind centrosomes and microtubule asters. (N) Merge of K, L, and M; (R) merge of O, P, and Q. Red, green, and blue in the merged images indicate labeling of DNA, αTUB, and γTUB, respectively.

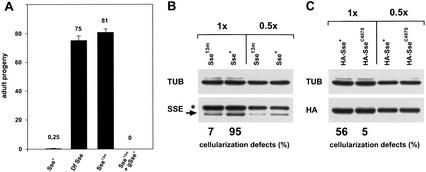

Figure 6.

THR cleavage limits SSE activity. (A) Females carrying two copies of the gthrΔVQ–myc transgene in a genetic background that was Sse+/Sse+ (Sse+), Df(3L)SseA/Sse+ (Df Sse), Sse13m/Sse+ (Sse13m), or Sse13m, gSse+/Sse+ (Sse13m + gSse+) were crossed to w1 males. Df(3L)SseA deletes Sse; Sse13m is a null allele and gSse+ is a transgene constructed with a genomic fragment providing Sse+ function (Jäger et al. 2001). Progeny developing at 18°C were counted. Average values of progeny/day and females obtained from at least four independent experiments are given for each cross. (B,C) Females carrying two copies of the gthrΔVQ–myc transgene in a genetic background that was either Sse+/Sse+ (Sse+) or Sse13m/Sse+ (Sse13m) were crossed to w1 males (B). Females that carried two copies of the gthrΔVQ–myc transgene in an Sse13m/Sse+ genetic background and in addition expressed HA–Sse+ (HA–Sse+) or HA–SseC497S (HA–SseC497S) were also crossed to w1 males (C). HA–SseC497S encodes a catalytically inactive SSE mutant. Embryos from these crosses were used to quantitate cellularization defects at 18°C and to prepare protein extracts for immunoblotting. Extracts were loaded either undiluted (1×) or in a 1:2 dilution (0.5×). Blots were probed with antibodies against SSE (SSE; arrow in B), the HA epitope (HA; C) or tubulin (TUB) as a loading control. The asterisk in B indicates a cross-reacting band.

The cold-sensitive developmental period of the maternal-effect lethality was defined by temperature-shift experiments. When eggs were collected at 25°C for 1 h and allowed to develop further at 25°C, the larval hatch rate of progeny from females with two gthrRD–myc, gthrΔVQ–myc, or gthr–myc transgene copies was indistinguishably high (Fig. 5A, gray bars). However, when the eggs were incubated at 18°C for 4.5 h followed by an up-shift to 25°C for the rest of embryogenesis, we observed a dramatic decrease in the larval hatch rates of progeny from females with either two gthrRD–myc or gthrΔVQ–myc transgenes, whereas the progeny from females with two gthr–myc transgenes still hatched with high efficiency (Fig. 5A, black bars). A reciprocal temperature-shift experiment revealed that embryonic lethality of progeny from females with two gthrΔVQ–myc transgenes is no longer observed when the whole embryogenesis, except for the first 3.5 h, takes place at 18°C (Fig. 5A, hatched bar). We conclude, therefore, that the cold-sensitive period covers the early stages of Drosophila embryogenesis that are characterized by rapid syncytial division cycles followed by cellularization.

To analyze the maternal-effect phenotype caused by noncleavable THR variants on a cellular level, we first examined embryos that had progressed through early development at 18°C, after fixation and DNA labeling (Fig. 5B,C; data not shown). These stainings suggested that progression through the rapid syncytial cycles is affected by noncleavable THR, although not severely. In the following, we refer to progeny from females with two gthrRD–myc, gthrΔVQ–myc, or gthr–myc transgene copies as THRRD, THRΔVQ, and THR embryos, respectively. A fraction of the syncytial THRRD (19%, n = 317) and THRΔVQ embryos (35%, n = 269) displayed various irregularities that were less frequent in THR embryos (12%, n = 250). Irregularities included embryonic regions with prominent mitotic asynchrony, abnormal mitotic figures or lower nuclear densities. Moreover, many THRΔVQ and THRRD embryos with an apparently regular nuclear distribution were found to have fewer nuclei compared with THR embryos of the same age. All these observations indicate that the noncleavable THR variants cause occasional cell cycle defects during the syncytial cycles with limited penetrance.

A much more severe and highly penetrant phenotype was observed during cellularization. This developmental process follows after the last syncytial division, mitosis 13. During cellularization, the ∼6000 nuclei at the syncytial egg periphery are enclosed by cell membranes and thereby transformed into individual cells forming a single layer epithelium (Foe et al. 1993). At this stage, THRΔVQ and THRRD embryos were found to lose a large fraction of nuclei from the egg periphery (Fig. 5C,H–J). These nuclei accumulated in the yolk region in the egg interior (Fig. 5C). In contrast, THR embryos had a normal appearance, with the majority of the nuclei at the periphery and only few yolk nuclei in the interior (Fig. 5B). This cellularization defect was displayed by 99% of the THRΔVQ embryos (n = 112) and 98% of the THRRD embryos (n = 53), but none of the THR embryos was affected (n = 49). Time-lapse imaging of THRΔVQ embryos expressing a histone–GFP fusion (Clarkson and Saint 1999) indicated that this massive loss of nuclei from the egg periphery started well after completion of mitosis 13, concomitant with the early slow phase of cellularization, which is paralleled by nuclear elongation (Foe et al. 1993). The loss of nuclei from the periphery of THRΔVQ embryos was found to continue throughout cellularization (data not shown).

Immunolabeling of fixed THRΔVQ embryos with an antibody against the Drosophila β-catenin homolog Armadillo (ARM), which displays a well-characterized dynamic behavior during cellularization (Hunter and Wieschaus 2000), confirmed that the massive nuclear loss started simultaneously with cellularization (Fig. 5D–J). Moreover, these stainings also indicated that cellularization, as revealed by ARM relocalization, was delayed in THRΔVQ embryos compared with nuclear elongation.

Immunolabeling with antibodies against γ-tubulin and α-tubulin indicated that parallel with the onset of cellularization, microtubule organization also became abnormal in THRΔVQ embryos. γ-Tubulin labeling in centrosomes was reproducibly weaker and revealed an impaired centrosome separation in THRΔVQ embryos (Fig. 5, cf. K and O). Microtubule asters were found to be slightly smaller (Fig. 5, cf. L and P). Centrosomes and associated microtubule asters were observed to stay at the cortex above interiorly displaced nuclei (Fig. 5O–R, arrowheads).

SSE is negatively regulated by mitotic THR cleavage

Mitotic THR cleavage might regulate the activity of the associated SSE. The maternal-effect lethality resulting from noncleavable THR at 18°C therefore might reflect either hyper- or hypoactivation of SSE. To address this issue, we analyzed the effects of a reduced Sse+ gene dose on the gthrΔVQ–myc phenotype. A reduction from two to one functional Sse+ gene copies was found to result in a strong suppression of the maternal-effect lethality caused by two gthrΔVQ–myc transgene copies at 18°C (Fig. 6A). This suppression was completely reverted, when one copy of a fully functional genomic Sse+ transgene was crossed into the females with only one endogenous Sse+ locus and two gthrΔVQ–myc transgene copies (Fig. 6A), showing that it is in fact the Sse+ copy number, and not potential second-site mutations, that affects the expression of the gthrΔVQ–myc phenotype.

Not only maternal-effect lethality but also the cellularization defects were affected by the Sse+ copy number. Massive nuclear loss from the egg periphery at 18°C was observed in 7% of THRΔVQ embryos (n = 133), when the mothers had only one Sse+ copy. In contrast, 95% of THRΔVQ embryos derived from sibling females with two Sse+ copies were affected (n = 119). Quantitative immunoblotting experiments showed that SSE protein levels during early embryogenesis were almost twofold higher in these THRΔVQ embryos from mothers with two Sse+ copies (Fig. 6B, cf. lane labeled Sse13m, 1× and lane labeled Sse+, 0.5×). We conclude, therefore, that the cellularization defects caused by noncleavable THR variants depend on high SSE protein levels.

To assess whether catalytic activity of SSE is required for the cellularization defects caused by noncleavable THR variants, we expressed a transgene (UAS–HA–SseC497S) encoding a catalytically inactive SSE mutant with a serine residue instead of the predicted catalytic cysteine residue (Jäger et al. 2001). Significantly, UAS–HA–SseC497S expression in THRΔVQ embryos from mothers with a single endogenous Sse+ locus did not increase the frequency and severity of cellularization defects. Only 5% of the embryos suffered from massive nuclear loss during cellularization (n = 300). In contrast, an analogous transgene (UAS–HA–Sse) allowing expression of wild-type SSE clearly induced cellularization defects in THRΔVQ embryos from mothers with a single endogenous Sse+ copy. In this case, 56% of the embryos displayed nuclear loss during cellularization (n = 317). Quantitative immunoblotting experiments showed that HA–SseC497S and HA–Sse were expressed at the same level (Fig. 6C). We conclude that noncleavable THR variants result in cellularization defects only in combination with catalytically active SSE. The cellularization defects caused by noncleavable THR versions at 18°C in embryos with wild-type SSE levels therefore reflect SSE hyperactivity. Consequently, our findings indicate that THR cleavage contributes to inactivation of SSE.

Discussion

Genetic stability in eukaryotes is critically dependent on the careful regulation of sister-chromatid cohesion. Cohesion between sister chromatids needs to be established during S phase and maintained until the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, when it must be rapidly and completely eliminated. This final elimination of cohesion is known to result from proteolytic cleavage of the Scc1 subunit of the cohesion complex by the endopeptidase separase. Because Scc1 cleavage is irreversible, separase activity has to be tightly regulated. Previous findings have implicated the securins, which bind as inhibitory regulatory subunits to separase in the corresponding control pathway (Funabiki et al. 1996a; Ciosk et al. 1998; Zou et al. 1999). In addition, recent studies have emphasized the regulatory role of phosphorylation of Scc1 and separase (Alexandru et al. 2001; Stemmann et al. 2001). Our studies indicate yet an additional level of control, the proteolytic cleavage of the THR subunit of the Drosophila separase complex. Moreover, they emphasize that Drosophila separase regulation is not only crucial for controlled cleavage of cohesin subunits, but for that of additional substrates as well.

Immunolabeling revealed that THR is partially degraded after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, similar to PIM. However, the mitotic degradation of PIM and THR is mechanistically and functionally distinct. Mitotic degradation of PIM is dependent on the presence of a destruction box (D-Box) and on Fizzy-APC/C, which promotes ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome (Leismann et al. 2000). This PIM degradation presumably leads to activation of SSE.

In contrast, THR does not seem to contain a functional D-box (data not shown), and mitotic degradation of THR is dependent on SSE. The initial THR cleavage event is followed by degradation of the C-terminal cleavage product. By analogy with the fate of the C-terminal cleavage product of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Scc1, we assume that this degradation follows the N-end rule (Rao et al. 2001). Furthermore, rather than activating SSE as in the case of PIM degradation, THR cleavage contributes to inactivation of SSE.

According to this proposal, degradation of PIM should precede THR cleavage, as these two events would define a window of SSE activity. THR cleavage should not occur too fast after PIM degradation so that SSE can cleave its other targets. THR cleavage therefore might be regulated (for instance, by Scc1 cleavage fragments) or might not lead to SSE inactivation immediately. SSE inactivation might occur only once THR cleavage fragments have been removed. Alternatively, SSE might cleave its substrates with different kinetics. Fast and efficient Scc1 cleavage may be followed by less efficient and slower THR cleavage.

We emphasize that we do not have direct evidence for our proposal from biochemical separase activity assays. The assay developed for human separase in the Xenopus extract system (Waizenegger et al. 2000) does not work for Drosophila SSE complexes for unknown reasons (A. Herzig, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.). Perhaps activation of Drosophila SSE complexes is only possible in a particular cellular context, for instance, on the mitotic spindle or at the kinetochore. Consistent with this proposal, only a fraction of PIM and THR is degraded during mitosis in Drosophila embryos, and a slight enrichment of PIM and THR on mitotic spindles, similar to securin and separase in yeast (Ciosk et al. 1998; Kumada et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2001), can be visualized with appropriate fixation procedures in the syncytial blastoderm (A. Herzig, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.).

Even without biochemical evidence, our data strongly support the notion that THR is cleaved by SSE. Cleavage occurs at a conserved separase-cleavage consensus sequence. Substitution of a single arginine by an aspartate within this region abolishes cleavage, as previously observed for cleavage of yeast and human Scc1 by separase (Uhlmann et al. 1999; Hauf et al. 2001). Furthermore, mitotic THR cleavage requires functional SSE complexes, as THR is neither cleaved in pim mutants, nor in SSE complexes containing nonfunctional THR mutants, nor in cells arrested in the mitotic checkpoint, when SSE is inactive.

The idea that THR cleavage and the consequential THR degradation contribute to inactivation of SSE is supported by our genetic analyses. Expression of noncleavable THR variants results in a phenotype that is highly dependent on the level of SSE protein. The phenotype is only observed with wild-type, but not with reduced levels of SSE. Moreover, noncleavable THR generates a phenotype only in combination with functional, but not with catalytically inactive SSE, having a serine instead of the cysteine residue in the catalytic center.

Does THR cleavage represent a general aspect of separase regulation or is it specific for Drosophila? THR is not conserved during evolution but might correspond to the nonconserved N-terminal domain found in separases from other eukaryotes. Therefore, mitotic THR cleavage might conceivably correspond to the mitotic separase cleavage, which has been observed in human tissue culture and in vitro (Waizenegger et al. 2000; Stemmann et al. 2001). This separase cleavage also appears to be autocatalytic. The cleavage sites in human separase have not yet been mapped precisely, and the functional consequences of cleavage-site mutations are not yet known (Stemmann et al. 2001). However, extrapolating from the reported size of the human separase cleavage fragments to Drosophila, the corresponding processing events should occur within SSE and not within THR, the putative N-terminal separase domain released during evolution. We have not detected SSE processing in Drosophila. But the hypothesized evolutionary gene split resulting in the independent Sse+ and thr+ genes of Drosophila might represent a permanent separation of those separase fragments that are generated by mitotic cleavage in human cells. The theory that mitotic THR cleavage does not correspond to human separase self-cleavage is also supported by the apparently distinct functional consequences of these processing events. Whereas THR cleavage contributes to SSE inactivation, cleaved human separase is clearly active (Stemmann et al. 2001). Mitotic THR cleavage therefore might be an event specific for insects with their characteristic early embryogenesis including syncytial division cycles followed by cellularization. Early embryogenesis is precisely the developmental period that is most dependent on THR cleavage. We do not understand why THR cleavage is essential at 18°C but largely dispensable at 25°C. The reason for this cold-sensitivity is not simply stress per se, because we did not observe sensitivity at elevated temperatures. We note that microtubule-dependent processes tend to be sensitive to cold temperatures (Brinkley and Cartwright 1975; Rieder 1981).

At present, we also do not understand why THR cleavage is particularly crucial for the process of cellularization, whereas it is less important during other developmental stages. As THR cleavage contributes to SSE inactivation, the phenotypes caused by noncleavable THR variants presumably reflect SSE hyperactivation. Persistence of SSE activity into S phase might be expected to interfere with the establishment of sister-chromatid cohesion by premature degradation of the Scc1 cohesin subunit. A rapid SSE inactivation resulting from mitotic THR cleavage, therefore, would be expected to be most important during the extremely rapid syncytial division cycles, during which the alternative pathway of SSE inhibition by resynthesis of the securin PIM during interphase might not be fast enough. In principle, the various irregularities observed during the syncytial cycles in THRΔVQ embryos might reflect consequences from premature Scc1 degradation by hyperactive SSE. The limited penetrance and expressivity of these defects during the syncytial cycles, however, makes a detailed characterization difficult.

The highly penetrant phenotype observed during cellularization is very unlikely to result from premature Scc1 degradation. The extensive cellularization defects start well after completion of mitosis 13, which is at most subtly defective in a few nuclei. We therefore assume that hyperactive SSE results in the degradation of an unknown protein that is crucial for cellularization.

Observations in other organisms have also indicated that separase has other targets in addition to cohesin subunits. Caenorhabditis elegans separase appears to have targets whose cleavage is important for osmotic barrier and anterior–posterior axis formation in the fertilized egg (Siomos et al. 2001; Rappleye et al. 2002). Moreover, a bioinformatics survey has revealed 26 potential separase targets in the S. cerevisiae proteome (Rao et al. 2001), and the kinetochore-associated protein Slk19 has in fact been confirmed as a separase target. Cleavage of Slk19 has been shown to contribute to anaphase spindle stability (Sullivan et al. 2001). Even though a Drosophila ortholog for Slk19 cannot be identified, it is conceivable that spindle-associated proteins are also SSE targets in Drosophila. Excess cleavage of microtubule-associated targets important for cytoskeletal organization might thus cause the cellularization defects in THRΔVQ embryos, which clearly have an abnormal γ-tubulin distribution during interphase 14. The putative additional SSE targets might be exclusively or particularly important during cellularization. Alternatively, it is not excluded that the alternative pathway of SSE inhibition by PIM resynthesis is particularly inefficient before cellularization, because the decrease of maternal pim mRNA levels at this stage might not yet be fully compensated by zygotic pim expression.

In conclusion, although mitotic and meiotic cohesin subunits have been shown to be crucial targets of eukaryotic separases, recent results point to additional substrates involved in processes beyond sister-chromatid separation and to novel regulatory mechanisms. Analyses in different organisms, which have revealed surprisingly distinct aspects of separase regulation and function, will perhaps rapidly converge toward a complete picture.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks and crosses

The transgenic lines gthr–myc III.1 and gthr 445–1379–myc III.1 have been described previously (Leismann et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2001). gthr 1–1204–myc lines were generated analogously. gthrΔVQ–myc and gthrRD–myc lines were generated with modified gthr–myc constructs carrying the desired mutations introduced with the QuikChange Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Sse13m, Df(3L)SseA (Jäger et al. 2001), pim1 (Stratmann and Lehner 1996), and thr1B (Nüsslein-Volhard et al. 1984) have been described previously. An Sse13m chromosome carrying the transgene gSse+ III.1 was constructed by meiotic recombination. gSse+ III.1, UAS–HA–Sse III.1, and UAS–HA–SseC497S III.2 have been described previously (Jäger et al. 2001). The UAS transgenes were expressed using α4tub–GAL4–VP16 (Micklem et al. 1997). The T(2;3) TSTL CyO; TM6B, Tb balancer stock (TSTL) was a gift from Konrad Basler (Institute of Molecular Biology, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland).

To investigate the phenotype resulting from two gthrΔVQ–myc transgenes in a thr+ background, all six possible pairs of the transgenes gthrΔVQ–myc II.1, gthrΔVQ–myc II.2, gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, and gthrΔVQ–myc II.4 were combined by meiotic recombination. Females with the genotypes gthrΔVQ–myc II.n, gthrΔVQ–myc II.m/+; Df(3L)SseA/+ or gthrΔVQ–myc II.n, gthrΔVQ–myc II.m/+; Sse13m/+ or gthrΔVQ–myc II.n, gthrΔVQ–myc II.m/+; Sse13m, gSse+III.1/+ or gthrΔVQ–myc II.n, gthrΔVQ–myc II.m/+; TM3, Ser Act5c-GFP/+ were crossed to w1 males at 18°C. The letters n and m refer to the different transgene insertion numbers. For the experiment shown in Figure 6A, the chromosome gthrΔVQ–myc II.2, gthrΔVQ–myc II.3 was used. At least four vials with six females and eight to ten w1 males were set up for each cross; eggs were allowed to be laid for 7 days, and all eclosing progeny were counted. In all cases, the cold-sensitivity caused by the two gthrΔVQ–myc transgene insertions was strongly suppressed (at least 100-fold more progeny when the maternal Sse dose was reduced by 50%).

To determine the cold-sensitive period of the maternal-effect lethality resulting from noncleavable thr variants, eggs were collected from gthrRD–myc III.1, or gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, or gthr–myc III.1, or gthrΔVQ–myc II.3/+ females at 25°C for 1 h on apple juice agar plates. The agar plates were divided into three sectors. One sector was left at 25°C, one sector was shifted to 18°C after 3.5 h, and a third sector was incubated at 18°C for 4.5 h and then shifted back to 25°C for the rest of embryonic development. Each sector was used for the determination of larval hatch rates.

For the analysis of the phenotype associated with the maternal expression of two gthrΔVQ–myc transgenes in the presence of Gal4-inducible Sse transgenes, females with the genotype gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, gthrΔVQ–myc II.4/α4tub–GAL4–VP16; UAS–HA–Sse III.1/Sse13m, or gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, gthrΔVQ–myc II.4/α4tub–GAL4–VP16; UAS–HA–SseC497S III.2/Sse13m were generated. Control females had the genotype gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, gthrΔVQ–myc II.4/TSTL; UAS–HA–SseC497S III.2/TSTL or gthrΔVQ–myc II.3, gthrΔVQ–myc II.4/TSTL; Sse13m/TSTL. All females were crossed to w1 males. Eggs were collected at 25°C for 1 h and then incubated at 18°C for 4.5 h before fixation and DNA labeling. In addition, eggs were collected at 25°C for 2 h and used to prepare protein extracts for immunoblotting.

Coupled in vitro transcription and translation

To generate THR fragments in vitro, the regions coding for C-terminal domains starting at amino acids 954, 973, 995, 1013, and 1032 were enzymatically amplified and cloned into the vector pCITE2a (Novagen). The forward primers were designed to introduce a start codon immediately upstream of the following thr coding regions. The resulting plasmids were used as templates in coupled in vitro transcription and translation reactions using the TNT system (Promega). Next 0.1 μL of each in vitro reaction was run on a SDS-PAGE next to an extract prepared from pooled embryos synchronously progressing through anaphase 14 (see Fig. 1G). The extracts were subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-THR antibody.

Antibodies

Antibodies against α-tubulin (mAB DM1A; Neomarkers), γ-tubulin (GTU-88; Sigma), and secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) were obtained commercially. The anti-Armadillo antibody (mAb N2 7A1; Peifer et al. 1994) was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa). Antibodies against the human c-myc-epitope (mAb 9E10; Evan et al. 1985), the HA-epitope (mAb 12CA5; Niman et al. 1983), cyclin B (Jacobs et al. 1998), cyclin A (Lehner and O'Farrell 1989), PIM and SSE (Jäger et al. 2001), and THR (Leismann et al. 2000) have been described previously.

Immunoblotting and immunolabeling

Extracts from embryos at defined stages of mitosis 14 were obtained as described (Sauer et al. 1995). For the analysis of defined cell cycle stages during the syncytial blastoderm, embryos were fixed, stained with Hoechst 33258, and stored as described (Edgar et al. 1994). Embryos at the desired cell cycle stage were selected under an inverted fluorescence microscope and subsequently solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Hybond-ECL membranes and ECL-detection (Amersham Biosciences) were used for immunoblotting experiments.

For the analysis of THR during mitosis 14 by immunofluorescence, females with the genotype gthr–myc III.1/+, or gthrΔVQ–myc II.3/+, or gthr 445–1379–myc III.1/+, or gthr 1–1204–myc III.1/+ were crossed with w1 males. Embryos were collected from these crosses and fixed at the stage of mitosis 14.

To analyze the stability of THR in spindle checkpoint-arrested cells, we collected eggs from a cross between w1 males and gthr–myc III.1/+ females. Eggs were collected for 30 min and aged at 25°C for 150 min. The subsequent permeabilization and incubation with demecolcine (Sigma) were performed as described (Leismann et al. 2000). Control embryos were treated identically, except that demecolcine was omitted. For the immunoblot analysis shown in Figure 3G, methanol-fixed embryos were stained with Hoechst 33258 and examined microscopically. Only fertilized and morphologically intact embryos were selected for extract preparation.

For the analysis of THR–myc behavior in pim mutants, eggs were collected from a cross of pim1/CyO, P[w+, ftz–lacZ]; gthr–myc III.1/+ females and pim1/CyO, P[w+, ftz–lacZ] males. Eggs were collected for 90 min and aged at 25°C for 270 min, fixed and immunolabeled. pim mutant embryos progressing through mitosis 15 were identified by the characteristic pim phenotype revealed by the DNA staining (Stratmann and Lehner 1996).

For the analysis of the cellular phenotype caused by the presence of noncleavable THR, eggs were collected from gthrΔVQ–myc III.3, or gthrRD–myc III.1, or gthr–myc III.1 females at 25°C for 1 h. The eggs were incubated at 18°C for 3.5 h and then fixed and labeled with a DNA stain.

To quantify defects during syncytial divisions, embryos were counted that had a nuclear density lower than expected for cycle 13 and that displayed abnormalities in their DNA stain (mitotic arrest, asynchronous mitoses, large areas devoid of nuclei, very low density of nuclei on the embryo surface). Percentages were calculated from the total number of embryos that were examined.

To quantify defects during cellularization, all embryos were scored that had completed cellularization (as judged by nuclear morphology). Among these, embryos with >20 nuclei detached from the cortex were classified as having a cellularization defect. Percentages were calculated from the total number of scored cellularized embryos.

Some embryos of the same collections were fixed by heat/methanol treatment and labeled with an antibody against Armadillo and propidium iodide to stain DNA. Some embryos were formaldehyde fixed in the presence of taxol and double-labeled with antibodies against α-tubulin and γ-tubulin to visualize microtubules and centrosomes, respectively. Images were acquired using a Leica TCS-SP inverted confocal laser scanning microscope and the Leica confocal software package. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Jan-Michael Peters and Irene Waizenegger for generously providing Xenopus extract and information. We thank K. Angermann and K. Neugebauer for technical help. We also thank H. Jäger for information concerning the thr orthologs from D. pseudoobscura and D. virilis. The work was supported by DFG grants (LE 987/2-1 and LE 987/3-1).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL stefan.heidmann@uni-bayreuth.de; FAX 49-921-55-2710.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.242202.

References

- Alexandru G, Uhlmann F, Mechtler K, Poupart MA, Nasmyth K. Phosphorylation of the cohesin subunit Scc1 by Polo/Cdc5 kinase regulates sister chromatid separation in yeast. Cell. 2001;105:459–472. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley BR, Cartwright J., Jr Cold-labile and cold-stable microtubules in the mitotic spindle of mammalian cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1975;253:428–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb19218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Puri R, Lefkowitz EJ, Kakar SS. Identification of the human pituitary tumor transforming gene (hPTTG) family: Molecular structure, expression, and chromosomal localization. Gene. 2000;248:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson M, Saint R. A His2AvDGFP fusion gene complements a lethal His2AvD mutant allele and provides an in vivo marker for Drosophila chromosome behavior. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18:457–462. doi: 10.1089/104454999315178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea RJ, Stratmann R, Lehner CF, John UP, Saint R. The three rows gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a novel protein that is required for chromosome disjunction during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1161–1174. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, Sprenger F, Duronio RJ, Leopold P, O'Farrell PH. Distinct molecular mechanisms regulate cell cycle timing at successive stages of Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:440–452. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan GI, Lewis GK, Ramsay G, Bishop JM. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies specific for human c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3610–3616. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE. Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1989;107:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE, Odell GM, Edgar BA. Mitosis and morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo: point and counterpoint. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 149–300. [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Fission yeast Cut1 and Cut2 are essential for sister separation, concentrate along the metaphase spindle and form large complexes. EMBO J. 1996a;15:6617–6628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Yamano H, Kumada K, Nagao K, Hunt T, Yanagida M. Cut2 proteolysis required for sister-chromatid separation in fission yeast. Nature. 1996b;381:438–441. doi: 10.1038/381438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf S, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM. Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells. Science. 2001;293:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1061376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Wieschaus E. Regulated expression of nullo is required for the formation of distinct apical and basal adherens junctions in the Drosophila blastoderm. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs HW, Knoblich JA, Lehner CF. Drosophila cyclin B3 is required for female fertility and is dispensable for mitosis like cyclin B. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3741–3751. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger H, Herzig A, Lehner CF, Heidmann S. Drosophila separase is required for sister chromatid separation and binds to PIM and THR. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:2572–2584. doi: 10.1101/gad.207301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallepalli PV, Waizenegger IC, Bunz F, Langer S, Speicher MR, Peters JM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Securin is required for chromosomal stability in human cells. Cell. 2001;105:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S, Segal M, Clarke DJ, Reed SI. A novel role of the budding yeast separin Esp1 in anaphase spindle elongation: Evidence that proper spindle association of Esp1 is regulated by Pds1. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:27–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada K, Nakamura T, Nagao K, Funabiki H, Nakagawa T, Yanagida M. Cut1 is loaded onto the spindle by binding to Cut2 and promotes anaphase spindle movement upon Cut2 proteolysis. Curr Biol. 1998;8:633–641. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner CF, O'Farrell PH. Expression and function of Drosophila cyclin A during embryonic cell cycle progression. Cell. 1989;56:957–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leismann O, Herzig A, Heidmann S, Lehner CF. Degradation of Drosophila PIM regulates sister chromatid separation during mitosis. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2192–2205. doi: 10.1101/gad.176700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J, Huang X, Zhang P. Securin is not required for cellular viability, but is required for normal growth of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1197–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklem DR, Dasgupta R, Elliott H, Gergely F, Davidson C, Brand A, González-Reyes A, St. Johnston D. The mago nashi gene is required for the polarisation of the oocyte and the formation of perpendicular axes in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1997;7:468–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niman HL, Houghten RA, Walker LE, Reisfeld RA, Wilson IA, Hogle JM, Lerner RA. Generation of protein-reactive antibodies by short peptides is an event of high frequency: Implications for the structural basis of immune recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1983;80:4949–4953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E, Kluding H. Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Zygotic loci on the second chromosome. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1984;193:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00848156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M, Sweeton D, Casey M, Wieschaus E. Wingless signal and Zeste-white 3 kinase trigger opposing changes in the intracellular distribution of Armadillo. Development. 1994;120:369–380. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp AV, Axton JM, Saunders RDC, Glover DM. Mutations in the Drosophila melanogaster gene three rows permit aspects of mitosis to continue in the absence of chromatid segregation. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:87–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao H, Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K, Varshavsky A. Degradation of a cohesin subunit by the N-end rule pathway is essential for chromosome stability. Nature. 2001;410:955–959. doi: 10.1038/35073627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappleye CA, Tagawa A, Lyczak R, Bowerman B, Aroian RV. The anaphase-promoting complex and separin are required for embryonic anterior–posterior axis formation. Dev Cell. 2002;2:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder CL. The structure of the cold-stable kinetochore fiber in metaphase PtK1 cells. Chromosoma. 1981;84:145–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00293368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer K, Knoblich JA, Richardson H, Lehner CF. Distinct modes of cyclin E/cdc2c kinase regulation and S phase control in mitotic and endoreduplication cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1327–1339. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah JV, Cleveland DW. Waiting for anaphase: Mad2 and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Cell. 2000;103:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomos MF, Badrinath A, Pasierbek P, Livingstone D, White J, Glotzer M, Nasmyth K. Separase is required for chromosome segregation during meiosis I in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1825–1835. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmann O, Zou H, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Kirschner MW. Dual inhibition of sister chromatid separation at metaphase. Cell. 2001;107:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratmann R, Lehner CF. Separation of sister chromatids in mitosis requires the Drosophila pimples product, a protein degraded after the metaphase anaphase transition. Cell. 1996;84:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Lehane C, Uhlmann F. Orchestrating anaphase and mitotic exit: Separase cleavage and localization of Slk19. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:771–777. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature. 1999;400:37–42. doi: 10.1038/21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger IC, Hauf S, Meinke A, Peters JM. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 2000;103:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Yu R, Melmed S. Mice lacking pituitary tumor transforming gene show testicular and splenic hypoplasia, thymic hyperplasia, thrombocytopenia, aberrant cell cycle progression, and premature centromere division. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1870–1879. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield WGF, Gonzalez C, Maldonado-Codina G, Glover DM. The A-type and B-type cyclins of Drosophila are accumulated and destroyed in temporally distinct events that define separable phases of the G2–M transition. EMBO J. 1990;9:2563–2572. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Guacci V, Koshland D. Pds1p, an inhibitor of anaphase in budding yeast, plays a critical role in the APC and checkpoint pathway(s) J Cell Biol. 1996;133:99–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, McGarry TJ, Bernal T, Kirschner MW. Identification of a vertebrate sister-chromatid separation inhibitor involved in transformation and tumorigenesis. Science. 1999;285:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]