Abstract

Aims

To investigate how risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of several drug classes is perceived by health vs non health professionals.

Methods

Four hundred health professionals (i.e. 278 general practitioners, 76 pharmacists and 46 pharmacovigilance professionals) and 153 non health professionals were interviewed. Visual analogue scales were used to define a score of perceived risk of ADRs associated with each drug class (ranking from 0 to 10).

Results

Anticoagulants were ranked as the most dangerous drugs by general practitioners [median score (25th-75th centiles): 7.9 (6.7–9.0)], pharmacists [8.7 (7.8–9.7)] and pharmacovigilance professionals [8.1 (7.2–9.0)]. For non health professionals, the class ranked first was sleeping pills [8.7 (7.2–9.4)] followed by tranquillisers [8.2 (6.4–9.2)] and antidepressants [8.0 (5.9–9.1)]. Aspirin was listed in the last position by non health professionals [3.4 (1.5–5.4)].

Conclusions

There are major differences in the perception of risk of ADRs between health professionals and non health professionals.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, general population, general practitioner, pharmacist, pharmacovigilance, risk

Introduction

A recent study performed in medical departments of French hospitals found an incidence of 3.2% (95% confidence interval [2.4%, 4.0%]) of hospital admissions related to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [1]. In highly developed industrialized countries, ADRs could be incriminated in approximately 5% of total hospital admissions [2, 3]. ADRs may also lengthen duration of hospitalizations [4]. Despite this large impact on hospital and daily medical practice, a large proportion of health professionals still do not consider ADRs as a relevant problem [5]. Under-reporting of ADRs is frequent, especially when they are not potentially life-threatening or when they do not involve newly marketed drugs [6–10]. In order to better understand how ADRs are perceived in medical practice and by the general public, we used a visual analogue scale questionnaire to assess the risk of ADRs associated with the most widely used drug classes.

Methods

Population

The study was carried out in winter 2000. A sample of 153 French adults selected from the general population (non health professionals) and 400 health professionals [278 general practitioners, 76 pharmacists and 46 pharmacologists (physicians or pharmacists) working in a Regional Pharmacovigilance Centre] was studied. Data were anonymously collected. Non health professionals were recruited in a commercial shopping mall: consecutive people (older than 18 years) coming in the mall were asked to participate in the study. They all received full explanations about the study before giving their consent to participate. People studying or working in health fields were excluded. The recruitment of health professionals was performed by mail. General practitioners and pharmacists working in the Toulouse area (South-western France) received a letter describing the aim and design of the study. The response rate was 46.3% and 50.7%, respectively, for general practitioners and pharmacists. A letter was also sent to the physicians and pharmacists working in the 31 French Pharmacovigilance Centres. Students were excluded. For each centre, at least one physician or pharmacist answered the questionnaire.

Assessment of perceived risks of ADRs

Participants were asked to assess their perception of the risk of ADRs associated with 13 different drug classes using visual analogue scales. We deliberately used everyday words to define drug classes and a therapeutic classification since the latter was more likely to be understood by subjects who were not working in health fields: antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, anticoagulants, antidepressants, tranquillisers, sleeping pills, drugs for arterial hypertension, hypocholesterolaemic drugs, insulin, drugs for diabetes (other than insulin), contraceptive pill and postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. For each drug class, the perceived risk of ADRs was assessed by measuring the distance between the left extremity of the scale (equal to zero) and the mark made by the participant. Since each scale measured 10 cm, the perceived risk of ADRs could be considered as a quantitative score ranging from 0 to 10. A non parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare scores between general practitioners, pharmacists, pharmacovigilance professionals and non health professionals. Results are shown as median values (25th−75th centiles).

Results

General practitioners were mainly men (74.8%) whereas this proportion was smaller in pharmacists (42.1%) and in pharmacovigilance professionals (19.6%). Mean age was 46.7 years (s.d. 8.8) in general practitioners, 44.4 (10.1) in pharmacists and 41.7 (8.3) in pharmacovigilance professionals. Only 17.6% of general practitioners mentioned that they had reported ADRs to a pharmacovigilance centre during the last 12 months. This proportion was higher in pharmacists (38.2%) (P < 0.001 general practitioners vs pharmacists). Non health professionals [mean age: 39.8 years (13.7)] were mainly women (62.7%). The percentage of subjects who had graduated from secondary school was 54.2%. Medical consultations were frequent: 85.6% of people had consulted a general practitioner during the last 12 months and 66.0% had consulted a specialist. The use of drugs with or without prescription was observed in 57.5% and 67.3%, respectively.

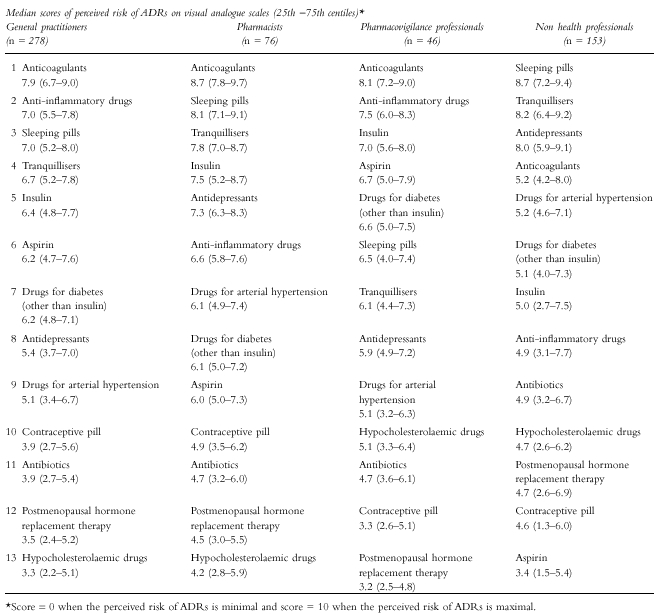

Drug classes were ranked according to the median score of perceived risk of ADRs obtained in general practitioners, pharmacists, pharmacovigilance professionals and non health professionals (Table 1). Non parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests comparing scores between the four groups of subjects were significant for all drug classes (P < 0.0001 for anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, anticoagulants, antidepressants, tranquillisers, sleeping pills, hypocholesterolaemic drugs and insulin, P < 0.001 for drugs for arterial hypertension and antibiotics, P < 0.01 for contraceptive pill and postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and P < 0.05 for drugs for diabetes other than insulin).

Table 1.

Perceived risks of ADRs.

Score = 0 when the perceived risk of ADRs is minimal and score = 10 when the perceived risk of ADRs is maximal.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate putative differences between health professionals and non health professionals in the perceived risk of ADRs. Our aim was not to assess a level of risk perception for each drug class but to determine whether the perceived risk of ADRs differs between health and non health professionals.

Previous studies have investigated the opinion and the awareness of general practitioners, specialists and pharmacists about the risk of ADRs associated with various drug classes [5–10]. The opinion of the public has been rarely studied. Our results allow a comparison between the perception of health and non health professionals. However, the general population sample analysed in this study was characterized by a rather high socio-economic level and young age, probably explained by the recruitment of the sample in a commercial shopping mall. It is difficult to determine to what extent this could have affected our results, but it might be assumed that the differences observed between the general population and health professionals would have been even larger with a more representative population-based sample.

Subjects working in health fields gave the highest score to anticoagulants and both general practitioners and pharmacovigilance professionals ranked anti-inflammatory drugs in second position. Non health professionals ranked anti-inflammatory drugs in eighth position and considered that aspirin was the least dangerous drug whereas psychotropics were considered as the most dangerous. The fact that the media report that psychotropics are frequently implicated in suicide attempts and the knowledge by the public about psychotropic-induced dependence may probably have contributed to this perception [11].

Drugs most often responsible for serious ADRs, such as anticoagulants, were not considered as the most harmful drugs by non health professionals. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not rank high for perceived risk of ADRs in non health professionals. However, their ADRs are frequent, particularly for the gastrointestinal tract [12–17]. In the United States, there are approximately 41 000 hospitalizations and 3300 deaths each year among the elderly related to NSAIDs [18]. Our results show that non health professionals do not seem to be aware of these potentially serious ADRs. Similar remarks are true for aspirin which was ranked at the thirteenth and last position by the general public. We studied aspirin separately from NSAIDs since it is easily obtained over-the-counter and used by the whole family. Our results show that the public does not know and clearly underestimates the risk associated with aspirin. In fact, the general population perception mainly reflects individual experience and education provided by general practitioners.

In conclusion, these results clearly show major differences in the perceived risk associated with drug use between health and non health professionals. They underline the need of a better communication on drugs for general population, concerning not only benefits but also risks.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the general practitioners, the pharmacists and the 31 French Regional Pharmacovigilance Centres for their participation in the study. Doctor Atul Pathak reviewed the English form of the paper.

References

- 1.Pouyanne P, Haramburu F, Imbs JL, Bégaud B. Admissions to hospital caused by adverse drug reactions: cross sectional incidence study. Br Med J. 2000;320:1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einarson TR. Drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:832–840. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosentino M, Leoni O, Oria C, et al. Hospital-based survey of doctors' attitudes to adverse drug reactions and perception of drug-related risk for adverse reaction occurrence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 1999;8:S27–S35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1557(199904)8:1+<s27::aid-pds407>3.3.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosentino M, Leoni O, Banfi F, Lecchini S, Frigo G. Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting by medical practitioners in a Northern Italian district. Pharmacol Res. 1997;35:85–88. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1996.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eland IA, Belton KJ, van Grootheest AC, Meiners AP, Rawlins MD, Stricker BH. Attitudinal survey of voluntary reporting of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:623–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Requejo A, Carvajal A, Bégaud B, Moride Y, Vega T, Arias LH. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions. Estimate based on a spontaneous reporting scheme and a sentinel system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:483–488. doi: 10.1007/s002280050498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweis D, Wong IC. A survey on factors that could affect adverse drug reaction reporting according to hospital pharmacists in Great Britain. Drug Saf. 2000;23:165–172. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moride Y, Haramburu F, Requejo AA, Bégaud B. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions in general practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:177–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.05417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck F, Peretti-Watel P. Observatoire Français des Drogues et Toxicomanies. EROPP 99. Enquête sur les représentations, opinions et perceptions relatives aux psychotropes. http://www.drogues.gouv.fr.

- 12.Hernandez-Diaz S, Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2093–2099. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Epidemiology of NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(Suppl 56):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenenbaum J. The epidemiology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:119–122. doi: 10.1155/1999/361651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-related gastrointestinal toxicity: definitions and epidemiology. Am J Med. 1998;105:3S–9S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe F. The epidemiology of NSAID associated gastrointestinal disease. Eur J Rheumatol Inflamm. 1991;11:12–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haslock I. Prevalence of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal morbidity and mortality. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1990;20:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin MR. Epidemiology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastrointestinal injury. Am J Med. 1998;104:23S–29S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]