Abstract

Aims

To compare the lipid-regulating effects and steady-state pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin, a new synthetic hydroxy methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor, following repeated morning and evening administration in volunteers with fasting serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations < 4.14 mmol l−1.

Methods

In this open-label two-way crossover trial 24 healthy adult volunteers were randomized to receive rosuvastatin 10 mg orally each morning (07.00 h) or evening (18.00 h) for 14 days. After a 4 week washout period, volunteers received the alternative regimen for 14 days. Rosuvastatin was administered in the absence of food.

Results

Reductions from baseline in serum concentrations of LDL-C (−41.3% [morning] vs −44.2% [evening]), total cholesterol (−30.9% vs −31.8%), triglycerides (−17.1% vs −22.7%), and apolipoprotein B (−32.4% vs −35.3%) were similar following morning and evening administration. AUC(0,24 h) for plasma mevalonic acid (MVA), an in vivo marker of HMG-CoA reductase activity, decreased by −29.9% (morning) vs −32.6% (evening). Urinary excretion of MVA declined by −33.6% (morning) vs −29.2% (evening). The steady-state pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin were very similar following the morning and evening dosing regimens. The Cmax values were 4.58 vs 4.54 ng ml−1, and AUC(0,24 h) values were 40.1 vs 42.7 ng ml−1 h, following morning and evening administration, respectively. There were no serious adverse events during the trial, and rosuvastatin was well tolerated after morning and evening administration.

Conclusions

The pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin are not dependent on time of dosing. Morning or evening administration is equally effective in lowering LDL-C.

Keywords: HMG-CoA reductase, LDL-C, morning/evening dosing, rosuvastatin

Introduction

Hydroxy methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) currently form the mainstay of lipid-regulating therapy, and are the most effective agents for reducing serum cholesterol concentrations and cardiovascular mortality [1–3]. As competitive inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, statins block an early rate-limiting step in cholesterol biosynthesis: the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate [4]. Inhibition of hepatic cholesterol production results in up-regulation of hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptors, which are responsible for the clearance of circulating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and reduced hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein particles [5–7].

Since hepatic HMG-CoA reductase activity [8] and cholesterol biosynthesis [9] are greatest at night (circadian variation) it is generally recommended that statins be administered in the evening or at bedtime for maximal effect [2]. The lipid-regulating effects of most available statins – including fluvastatin [10], lovastatin [11], pravastatin [12], and simvastatin [13]– are reported to be influenced by the time of dosing, and are less pronounced following morning compared with evening administration.

Rosuvastatin (Crestor®) is a new and highly effective inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase that has completed Phase-III clinical development for the treatment of patients with dyslipidaemia. In clinical trials, rosuvastatin (1–80 mg) produced reductions in LDL-C, total cholesterol (TC), and triglycerides (TG), and increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [14–18].

The pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin following single- and multiple-dose administration of the drug to healthy volunteers have been investigated in a number of trials [19, 20, AstraZeneca data on file†]. Following multiple oral doses of rosuvastatin (20, 40, and 80 mg) AUC(0,24 h) and Cmax were essentially dose proportional, time to Cmax ranged from 3 to 5 h, and the terminal elimination half-life ranged from 13 to 21 h.

This trial (4522IL/0004) was conducted to compare the pharmacodynamics and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin following morning and evening administration in healthy adult volunteers.

Methods

Twenty-four healthy adult volunteers (22 men and 2 women), ranging in age from 19 to 61 years (mean 38.6 years) and weighing 57–100 kg (mean 76.9 kg), were enrolled in this trial. Of these, 21 were Caucasian, 2 were Hispanic, and 1 was Black.

Screening assessments included a complete medical history, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), and standard laboratory tests. All volunteers had fasting serum LDL-C concentrations < 4.14 mmol l−1 and fasting serum TG concentrations ≤ 3.39 mmol l−1. Clinical chemistry (including hepatic function) tests were within reference ranges. Each volunteer provided written in-formed consent prior to enrolment.

Trial design

This open-label, randomized, two-way crossover trial comprised two 14 day treatment periods separated by a 4 week washout period. Dietary assessments were made during a pre-treatment screening period of 21–30 days, and dietary regimens were developed to stabilize individual calorie and fat intake during the trial (thereby minimizing potential dietary effects on lipid levels). Volunteers entered the clinic 2 days before treatment began and remained there for each 14 day treatment period and for a 4 day follow-up period.

Eligible volunteers were randomized to receive a single oral dose of rosuvastatin (10 mg) each morning (approximately 07.00 h) or evening (approximately 18.00 h) for 14 days. After the washout period volunteers received the alternative (morning or evening) treatment regimen for a further 14 days. The trial medication was administered with 240 ml of water. Volunteers were required to fast for a minimum of 2 h before and after each rosuvastatin dose, and for at least 12 h (overnight) before collection of blood samples for lipid analyses.

The trial was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Covance in Madison, Wisconsin, USA approved the trial protocol.

Pharmacodynamic evaluations

Blood samples (10 ml) were collected for determination of fasting serum lipid concentrations before administration of the morning dose of rosuvastatin (morning dosing) or before the morning meal (evening dosing). Serum LDL-C (the primary parameter of this trial), TC, TG, HDL-C, apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) concentrations were determined at screening (days −21 and −1), on treatment days 1, 7, 13, and 14, at follow-up (days 1 and 4 post-treatment), and at weekly intervals during the washout period. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C prior to analysis, which was conducted at a central laboratory (Covance Laboratories, Indiana, USA). LDL-C concentrations were calculated using the Friedewald formula [21]. TC and TG were measured by colorimetric enzymatic assay (using a Hitachi 747 automatic analyser). HDL-C was measured after precipitation by colorimetric enzymatic assay. ApoA-I and ApoB were measured by nephelometry.

During each treatment period, plasma concentrations of mevalonic acid (MVA). an in vivo marker of HMG-CoA reductase activity, were measured at baseline (day −1), on treatment days 1 and 14, and at follow-up (day 1 post-treatment). In addition, urinary MVA excretion was determined over a 24 h period before the first dose and after the final dose of rosuvastatin in each treatment period. Heparinized plasma samples and urine samples were stored at −70 °C prior to analysis. The analysis of plasma MVA concentrations was performed using a validated h.p.l.c./MS/MS [22] method at Covance Laboratories, Harrogate, UK. Correlation coefficients for plasma MVA were 0.991–1.00. Mean accuracy levels for quality control samples (at all concentrations) were 99.7–106.7%; mean imprecision values were 7.2–10.9%. The limit of quantification for plasma MVA in this trial was 0.2 ng ml−1. The analysis of urine MVA concentrations was performed using a validated GC/MS assay [23] at AstraZeneca's Central Toxicology Laboratory, Alderley Park, Cheshire, UK. Correlation coefficients for urine MVA were 0.993–1.00. Mean accuracy levels for quality control samples (at all concentrations) were 86.6–103%. The limit of quantification for urine MVA in this trial was 9.0 ng ml−1.

Pharmacokinetics

Serial venous blood samples (7 ml) for determination of plasma rosuvastatin concentrations were collected at 0.5 h predose and at fixed intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 24, 48, and 72 h) after administration of rosuvastatin on treatment day 14. Blood samples were also collected at 0.5 h pre-dose on treatment days 2, 3, 7, 8, and 13 to assess whether pharmacokinetic steady state had been attained. Heparinized blood samples were centrifuged at 1500–2500 rev min−1 for 10 min. The derived plasma samples were diluted 1 : 1 with 0.1 m sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) and stored at −70 °C prior to analysis. Plasma concentrations of rosuvastatin were determined using a validated h.p.l.c./MS assay [24] at Quintiles, Edinburgh, UK. Correlation coefficients for rosuvastatin were 0.994–1.00. Mean inaccuracy levels and imprecision values for quality control samples (at all concentrations) were ≤ 7% and < 8%, respectively. The limit of quantification for rosuvastatin in this trial was 0.2 ng ml−1.

Plasma rosuvastatin concentration-time data were analysed by standard noncompartmental pharmacokinetic methods. The following parameters were determined: maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to 24 h (AUC(0,24 h)), AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC(0,∞)), and the plasma terminal elimination half-life (t1/2). AUC was estimated using the linear trapezoidal method, with extrapolation from the last quantifiable data point using the terminal slope of the plasma concentration-time profile. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was derived by log-linear regression of the terminal portion of the plasma concentration-time profile, and t1/2 was calculated as ln2/λz.

Safety and tolerability assessments

Safety and tolerability were assessed from routine laboratory tests, haemodynamic monitoring, and clinical adverse event records.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimates showed that 16 volunteers would be required in order to provide 80% power to detect an absolute treatment difference (morning-evening) of 10% in mean percent reduction in LDL-C concentration. Assuming a trial discontinuation rate of 33%, 24 volunteers were required for enrollment.

For morning vs evening comparisons of lipid parameters, MVA concentrations, and pharmacokinetic parameters an analysis of variance (anova) model was used (with effects for treatment sequence, volunteer-within-treatment sequence, treatment group, and period). Mean percent changes in lipid parameters from baseline were compared using least square means generated by anova of lipid parameters and expressed as morning-evening differences with 90% confidence intervals (CIs). Mean percent change in MVA concentrations from baseline were compared using least square geometric means generated by anova of plasma MVA AUC(0,24 h) and urinary excretion of MVA and expressed as morning-evening differences with 90% CIs. Plasma rosuvastatin exposure was compared using least square geometric means generated by anova of log-transformed rosuvastatin AUC(0,24 h) and Cmax values and expressed as morning/evening ratios with 90% CIs.

Results

Of the 24 volunteers enrolled in this trial, 21 were included in the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic analyses. Three volunteers were withdrawn because of protocol noncompliance (n = 1), loss to follow-up after the first treatment period (n = 1), and a nonserious adverse event (n = 1). All 24 volunteers were included in the safety analysis.

Pharmacodynamics

Similar marked reductions in serum LDL-C were obtained following once daily administration of rosuvastatin 10 mg in the morning or evening. After 14 days of treatment, the mean reductions from baseline in serum LDL-C concentration with the morning and evening regimens were −41.3% and −44.2%, respectively (Table 1). Any difference between treatments greater than 6%, was excluded by the 90% CIs.

Table 1.

Summary of serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations after morning and evening administration of rosuvastatin.

| Parameter | Morning n = 21 Mean baseline (mmol l−1) | Mean % change | Evening n = 21 Mean baseline(mmol l−1) | Mean % change | Treatment effecta (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C | 3.12 | −41.3 | 3.09 | −44.2 | 2.9 (−0.09, 5.85) |

| Total cholesterol | 4.94 | −30.9 | 4.90 | −31.8 | 0.8 (−1.21, 2.89) |

| Triglycerides | 1.19 | −17.1 | 1.27 | −22.7 | 5.7 (−0.39, 11.70) |

| HDL-C | 1.28 | −9.6 | 1.23 | −4.9 | −4.7 (−7.80, 1.54) |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | 16.6 | −6.0 | 20.3 | −3.4 | −2.6 (−5.40, 0.18) |

| Apolipoprotein B | 22.8 | −32.4 | 24.8 | −35.3 | 2.9 (0.25, 5.57) |

HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Treatment effect = difference of morning-evening least square means.

Likewise, the reductions in serum TC (−30.9% vs −31.8%), TG (−17.1% vs −22.7%), ApoA-I (−6.0% vs −3.4%), and ApoB (−32.4% vs −35.3%) concentrations were similar following morning and evening administration (Table 1).

Serum HDL-C showed a greater reduction following morning compared with evening administration (−9.6% vs −4.9%) (Table 1).

The reductions from baseline in LDL-C, TC, TG, and ApoB are consistent with the effect of rosuvastatin. The small reductions in HDL-C and ApoA-I are atypical.

Summary statistics for the plasma and urine MVA parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of plasma and urine mevalonic acid parameters after morning and evening administration of rosuvastatin.

| Parameters (units) | Morning | Evening n = 21 | 90% CIan = 21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trough plasma concentration (ng ml−1) | |||

| Mean baseline | 2.88 | 2.90 | NA |

| Mean day 14 | 1.45 | 1.54 | NA |

| Peak plasma concentration (ng ml−1) | |||

| Mean baseline | 7.55 | 7.53 | NA |

| Mean day 14 | 5.26 | 4.90 | NA |

| Mean percentage change | −25.9 | −31.0 | NA |

| Plasma AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1 h) | |||

| Mean baseline | 117 | 116 | NA |

| Mean day 14 | 79.1 | 72.9 | NA |

| Mean percentage change | −29.9 | −32.6 | −3.47, 8.10 |

| Daily urine excretion (µg) | |||

| Mean baseline | 197 | 240 | NA |

| Mean day 14 | 130 | 133 | NA |

| Mean ratio (day 14/baseline) | 0.664 | 0.708 | NA |

| Mean percentage change | −33.6 | −29.2 | −12.76, 3.81 |

CI – confidence interval. NA – not applicable.

90% CI for difference of morning-evening least square geometric means.

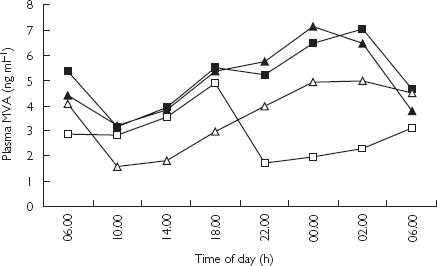

During the course of the 14 day treatment period, the mean percent reduction in peak plasma MVA concentration was −25.9% with morning dosing and −31.0% with evening dosing (Table 2). The mean percent reductions in plasma AUC(0,24 h) values for MVA were −29.9% and −32.6% after morning and evening dosing, respectively. The plasma MVA concentration-time curves are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geometric mean plasma mevalonic acid concentration-time profiles before, after morning and evening administration of rosuvastatin. ▴ morning pre-dose, ▪ evening pre-dose, ▵ morning post-dose, □ evening post-dose.

Over the same period, the mean percent reductions in 24 h urinary excretion of MVA were −33.6% and −29.2% after morning and evening dosing, respectively (Table 2).

The 90% CIs for the difference in mean percent change from baseline at day 14 between the morning and evening treatment groups for plasma MVA AUC(0,24 h) and urinary excretion of MVA were −3.47, 8.10 and −12.76, 3.81, respectively (Table 2).

Pharmacokinetics

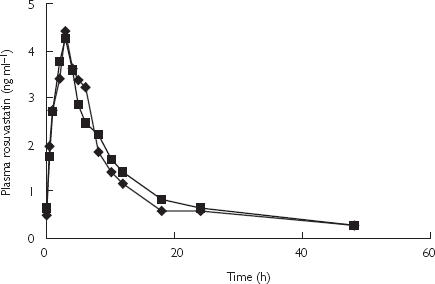

From inspection of trough plasma rosuvastatin concentration-time profiles, it was apparent that steady state was attained within 8 days of initiating once-daily rosuvastatin administration (with both morning and evening dosing regimens). Under steady-state conditions, the mean trough plasma rosuvastatin concentration was approximately 0.6 ng ml−1 in both treatment groups. Mean plasma concentration-time profiles on day 14 follow-ing morning or evening dosing were virtually super-imposable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geometric mean plasma rosuvastatin concentration-time profiles on day 14 after morning (♦) and evening (▪) administration of rosuvastatin.

The apparent rate of absorption of rosuvastatin was essentially the same following morning and evening dosing (median tmax 3.0 h) (Table 3). Likewise, the degree of systemic exposure was very similar: mean Cmax values of 4.58 and 4.54 ng ml−1, and mean AUC(0,24 h) values of 40.1 and 42.7 ng ml−1 h following morning and evening dosing, respectively. In addition, mean plasma t1/2 values were similar (31.3 and 26.5 h), supporting no diurnal variation in the disposition of rosuvastatin.

Table 3.

Summary of pharmacokinetic parameters for rosuvastatin after morning and evening administration of rosuvastatin.

| Parameter (units) | Morning n = 21 | Evening n = 21 | Treatment effecta (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 4.58b | 4.54b | 1.01 (0.88–1.15) |

| tmax (h) | 3.0c | 3.0c | NA |

| AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1 h) | 40.1b | 42.7b | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) |

| AUC(0,∞) (ng ml−1 h) | 71.8bd | 76.4bd | 0.96 (0.84–1.11)e |

| t1/2 (h) | 31.3fd | 26.5fd | 5.89 (0.91–10.88)e |

AUC(0,∞) – area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to infinity. AUC(0,24 h) – area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to 24 h. Cmax – peak plasma concentration. CI – confidence interval. LSM – least squares mean. NA – not applicable. t1/2 – plasma terminal elimination half-life. tmax– time to Cmax.

Treatment effect = ratio of morning/evening least square geometric means (except for t1/2: difference of morning-evening least square geometric means).

Geometric mean.

Median.

n = 16.

n = 14.

Arithmetic mean.

Any difference greater than 2% in the pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax and AUC(0,24 h)) for rosuvastatin between the morning and evening dosing regimens was excluded by the 90% CIs (Table 3).

Safety and tolerability

Rosuvastatin proved to be well tolerated over the two 14 day treatment periods, with no significant changes in laboratory parameters and no serious adverse events.

One volunteer (male, 43 years) was withdrawn from the trial because of transient nonspecific ECG changes (T-wave flattening, primarily in the lateral leads), which occurred 3.5 h after the first dose of rosuvastatin. The volunteer was asymptomatic and the T-wave abnormality resolved within 15 h of dosing. Food intake can lead to similar ECG changes in healthy subjects up to 5 h after ingestion [25]. Food may have been the causative factor for the changes noted in this volunteer, as he received food 1.5 h prior to the appearance of the abnormality.

Discussion

This trial was conducted to compare the pharmacodynamics and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin following morning and evening administration in healthy volunteers. The results show that rosuvastatin was equally effective in lowering serum LDL-C concentrations after morning or evening administration. In keeping with this finding, the steady-state pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin were very similar after morning and evening administration. This characteristic of dose-time independence for both pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics differentiates rosuvastatin from other marketed statins.

Fluvastatin [10], lovastatin [11], pravastatin [12], and simvastatin [13] all exert less pronounced LDL-C-regulating effects following morning compared with evening administration. Atorvastatin appears to be the only statin to share with rosuvastatin the characteristic of dose-time independence for pharmacodynamics [26]. The fact that both atorvastatin and rosuvastatin have relatively long plasma half-lives may be of relevance to this common characteristic. However, atorvastatin, unlike rosuvastatin, shows diurnal differences in plasma exposure: lower systemic bioavailability (plasma AUC values reduced by 30%) was observed after evening compared with morning administration [26].

The reductions in serum LDL-C concentrations observed in this trial (−41 to −44%) closely match those obtained in hypercholesterolaemic patients following treatment with rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily for 6 weeks (approximately −48%) [14]. While the reductions in TC, TG and ApoB concentrations observed in this trial are consistent with the effect of rosuvastatin on LDL-C, the small reductions in HDL-C and ApoA-I concentrations are less readily explainable. Data from dose-ranging [14] and Phase-III [15–18] trials show that rosuvastatin (1–80 mg) consistently raises HDL-C in dyslipidaemic patients. It is likely that the atypical decrease in HDL-C seen in this trial is the result of the relatively short treatment period (2 weeks) and the fact that volun-teers were required to have baseline LDL-C concentrations < 4.14 mmol l−1 and baseline TG concentrations ≤ 3.39 mmol l−1.

The marked reductions in plasma and urine MVA after morning and evening dosing are consistent with the observed reductions in LDL-C and with the inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. In addition, the similar reductions in MVA between morning and evening dosing concur with the similar pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics between morning and evening dosing.

In conclusion, the results of this trial indicate that the therapeutic benefit of rosuvastatin is not dose-time de-pendent, and that morning or evening administration is equally effective in regulating lipid levels. In addition, the pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin were independent of time of dosing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth Eaton PhD for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Trials 4522IL/0048, 0012 and 0053, 0057, and 0058.

References

- 1.Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH. Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:187–195. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knopp RH. Drug treatment of lipid disorders. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:498–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfire M, Coletti AT, Mosca L. Treatment strategies for management of serum lipids: lessons learned from lipid metabolism, recent clinical trials, and experience with the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1998;41:95–116. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(98)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–430. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilar-Salinas CA, Barrett H, Schonfeld G. Metabolic modes of action of the statins in the hyperlipoproteinemias. Atherosclerosis. 1998;141:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davignon J, Montigny M, Dufour R. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: a look back and a look ahead. Can J Cardiol. 1992;8:843–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lennernäs H, Fager G. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Similarities and differences. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:403–425. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker TS, McNamara DJ, Brown C, et al. Mevalonic acid in human plasma: relationship of concentration and circadian rhythm to cholesterol synthesis rates in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3037–3041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PJ, Schoeller DA. Evidence for diurnal periodicity in human cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:667–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy RI, Troendle AJ, Fattu JM. A quarter century of drug treatment of dyslipoproteinemia, with a focus on the new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor fluvastatin. Circulation. 1993;87(Suppl):III45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illingworth DR. Comparative efficacy of once versus twice daily mevinolin in the therapy of familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;40:338–343. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunninghake DB, Mellies MJ, Goldberg AC, et al. Efficacy and safety of pravastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. II. Once-daily versus twice-daily dosing. Atherosclerosis. 1990;85:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(90)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito Y, Yoshida S, Nakaya N, Hata Y, Goto Y. Comparison between morning and evening doses of simvastatin in hyperlipidemic subjects. A double-blind comparative study. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:816–826. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsson AG, Pears J, McKellar J, Mizan J, Raza A. Effect of rosuvastatin on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:504–508. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01727-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson M, Ma P, Stein EA, et al. Comparison of effects on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in patients with type IIa or IIb hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:268–275. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paoletti R, Fahmy M, Mahla G, Caplan R, Raza A. Rosuvastatin is more effective than pravastatin or simvastatin at improving the lipid profiles of hypercholesterolaemic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2001;2(Suppl 2):87–164. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein EA, Strutt KL, Miller E, Southworth H. Rosuvastatin (20, 40 and 80 mg) reduces LDL-C, raises HDL-C and achieves treatment goals more effectively than atorvastatin (20, 40 and 80 mg) in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis. 2001;2(Suppl 2):90–176. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunninghake DB, Chitra RR, Simonson SG, Schneck DW. Treatment of hypertriglyceridemic patients with rosuvastatin. Diabetes. 2001;50(Suppl 2):143–574. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warwick MJ, Dane AL, Raza A, Schneck DW. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of the new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor ZD4522. Atherosclerosis. 2000;151:39. ((Abstract) MoP19: W6) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin PD, Dane AL, Nwose OM, Schneck DW, Warwick MJ. No effect of age or gender on the pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin – a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002 doi: 10.1177/009127002401382722. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Frederickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of preparative ultracentrifugation. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrar M, Martin PD. Validation and application of an assay for the determination of mevalonic acid in human plasma by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2002;773:103–111. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woollen BH, Holme PC, Northway WJ, Martin PD. Determination of mevalonic acid in human urine as mevalonic acid lactone by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2001;760:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hull CK, Penman AD, Smith CK, Martin PD. Quantification of rosuvastatin in human plasma by automated solid-phase extraction using tandem mass-spectrometric detection. J Chromatogr B. 2002;772:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widerlöv E, Jostell KG, Claesson L, et al. Influence of food intake on electrocardiograms of healthy male volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:619–624. doi: 10.1007/s002280050682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cilla DD, Gibson DM, Whitfield LR, Sedman AJ. Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin after administration to normocholesterolemic subjects in the morning and evening. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:604–609. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]