Abstract

Aims

To investigate the effects of incubation conditions on the kinetic constants for zidovudine (AZT) glucuronidation by human liver microsomes, and whether microsomal intrinsic clearance (CLint) derived for the various conditions predicted hepatic AZT clearance by glucuronidation (CLH) in vivo.

Methods

The effects of incubation constituents, particularly buffer type (phosphate, Tris) and activators (Brij58, alamethacin, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-NAcG)), on the kinetics of AZT glucuronidation by human liver microsomes was investigated. AZT glucuronide (AZTG) formation by microsomal incubations was quantified by h.p.l.c. Microsomal CLint values determined for the various experimental conditions were extrapolated to a whole organ CLint and these data were used to calculate in vivo CLH using the well-stirred, parallel tube and dispersion models.

Results

Mean CLint values for Brij58 activated microsomes in both phosphate (3.66 ± 1.40 µl min−1 mg−1, 95% CI 1.92, 5.39) and Tris (3.79 ± 0.74 µl min−1 mg−1, 95% CI 2.87, 4.71) buffers were higher (P < 0.05) than the respective values for native microsomes (1.04 ± 0.42, 95% CI 0.53, 1.56 and 1.37 ± 0.30 µl min−1 mg−1, 95% CI 1.00, 1.73). Extrapolation of the microsomal data to a whole organ CLint and substitution of these values in the expressions for the well-stirred, parallel tube and dispersion models underestimated the known in vivo blood AZT clearance by glucuronidation by 6.5- to 23-fold (3.61–12.71 l h−1vs 82 l h−1). There was no significant difference in the CLH predicted by each of the models for each set of conditions. A wide range of incubation constituents and conditions were subsequently investigated to assess their effects on GAZT formation, including alamethacin, UDP-NAcG, MgCl2, d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone, ATP, GTP, and buffer pH and ionic strength. Of these, only decreasing the phosphate buffer concentration from 0.1 m to 0.02 m for Brij58 activated microsomes substantially increased the rate of GAZT formation, but the extrapolated CLH determined for this condition still underestimated known AZT glucuronidation clearance by more than 4-fold. AZT was shown not to bind nonspecifically to microsomes. Analysis of published data for other glucuronidated drugs confirmed a trend for microsomal CLint to underestimate in vivo CLH.

Conclusions

AZT glucuronidation kinetics by human liver microsomes are markedly dependent on incubation conditions, and there is a need for interlaboratory standardization. Extrapolation of in vitro CLint underestimates in vivo hepatic clearance of drugs eliminated by glucuronidation.

Keywords: glucuronidation, in vitro-in vivo correlation, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, zidovudine

Introduction

The use of in vitro methodologies to predict aspects of human drug metabolism in vivo has found increasing acceptance over the last decade, particularly for drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP). The economic imperatives of new drug development and greater awareness of the need for rational therapeutics have been primary considerations in the development of in vitro models. Prediction of human drug disposition parameters potentially decreases attrition of new drug candidates during clinical development by identifying those compounds with unacceptable pharmacokinetic characteristics, and at the same time optimizes clinical utility and market success of newly marketed drugs by selecting for development only those compounds with desirable pharmacokinetics [1]. Knowledge of the potential impact of drug interactions and genetic polymorphism on drug elimination is of importance for rationalizing and optimizing dosage regimens of both newly developed and established drugs [2].

In vitro-in vivo correlations may be qualitative or quantitative. At the qualitative level, identification of the isoform(s) responsible for the biotransformation of any given compound allows prediction of those factors (genetic polymorphism, drug–drug interactions) likely to influence metabolic clearance [2]. Quantitative prediction most commonly involves the scaling of an in vitro intrinsic clearance (CLint) for a metabolic pathway, normally calculated from microsomal or hepatocyte kinetic data, to hepatic clearance (CLH) in vivo using a mathematical model of hepatic drug clearance [3–8]. For example, microsomal CLint may be corrected for microsome yield and liver weight to obtain the ‘whole organ’ hepatic CLint, which subsequently is substituted in the expression for the well-stirred, parallel-tube, distributed or dispersion models.

The success of predictions of in vivo CLH is critically dependent on in vitro CLint, and hence how closely the kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km) used to derive this parameter reflect enzyme activity in vivo. Microsomal incubation components are known to modulate CYP activity and the kinetics of drug metabolite formation may therefore vary with experimental conditions. For example, it has been demonstrated that buffer type (phosphate, Tris) and ionic strength, the presence of certain salts, and stimulators of enzyme activity may variably affect the kinetic constants of CYP3A substrates determined in human liver microsomes [9]. These observations highlight the need to optimize experimental conditions in vitro if kinetic data are to be reliably extrapolated to the in vivo situation.

Despite the success of in vitro–in vivo correlations for drugs eliminated by CYP, few studies have investigated the reliability of extrapolating human liver microsomal kinetic data to an in vivo CLH for drugs metabolized by glucuronidation. UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) is quantitatively the most important conjugation enzyme, and drugs from all therapeutic classes are eliminated by glucuronidation [10]. Thus, establishment of an experimental paradigm which allows extrapolation of in vitro kinetic data to hepatic clearance in vivo assumes considerable importance. Like CYP, microsomal UGT activity is known to be dependent on experimental conditions, and hence the composition of the incubation mixture may influence the derived kinetic constants. Factors affecting UGT activity in vitro include the presence of activators (detergents, alamethacin, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-NAcG)), metal ions (especially Mg2+), buffer pH and ionic strength, ATP and GTP [11].

This paper describes studies which were performed to characterize the effects of buffer type (phosphate or Tris) and detergent (Brij58) activation on the human liver microsomal glucuronidation of the model glucuronidated drug zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine; AZT), and whether CLint values calculated using the various experimental conditions predicted hepatic AZT clearance by glucuronidation in vivo. While kinetic constants were found to vary with changes in the composition of the incubation mixture, CLint values determined for the various reaction conditions all underestimated in vivo metabolic clearance irrespective of the model of hepatic clearance used. Subsequent experiments were thus conducted to investigate the influence of nonspecific microsomal binding, a nondetergent activator (alamethacin), UDP-NAcG, pH, buffer type and ionic strength, MgCl2, d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone, ATP and GTP, on human liver microsomal AZT glucuronidation.

AZT was employed as the model substrate in this work since it is extensively glucuronidated and has high hepatic clearance (with possible dependence of extrapolated CLH on the mathematical model of hepatic drug clearance employed). Mean AZT systemic clearance ranges from 77 to 114 l h−1 normalized to 70 kg body weight [12–14], giving an average value of 94 l h−1 70 kg−1. Since 75% of the dose is recovered as AZT glucuronide (GAZT; AZT 5′-β-d-glucuronide) in urine [12], the plasma AZT clearance by glucuronidation in vivo may be taken as 70.5 l h−1 70 kg−1.

Methods

Chemicals, reagents and human tissue microsomes

Alamethacin, ATP, AZT, Brij58 (polyoxyethylene-20-cetyl ether), creatine kinase, creatine phosphate, GAZT (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine 5′-β-d-glucuronide), GTP, 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide (4-MUG), d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone, Tris-HCl, UDP-glucuronic acid (UDPGA), and UDP-NAcG were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals and reagents were of the highest grade available.

Microsomes were prepared from five human livers obtained from the human liver ‘bank’ of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Flinders Medical Centre, as described previously [15]. Approval was obtained from the Clinical Investigation Committee of Flinders Medical Centre and from the donor next-of-kin for the procurement and the use of human liver tissue in xenobiotic metabolism studies.

Microsomal incubations

GAZT formation by incubations of human liver microsomes was measured by a modification of the method of Sim et al. [16]. Incubation mixtures, in a total volume of 0.2 ml, typically contained microsomal protein (0.2 mg), AZT (50–4000 µm), MgCl2 (4 mm), phosphate (prepared from sodium dihydrogen phosphate and disodium hydrogen phosphate) or Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4). Duplicate samples were prepared for each added concentration of AZT. Reactions were initiated by the addition of UDPGA, such that the final concentration of cofactor was 10 mm. Reactions were carried out in air at 37 °C (shaking water bath), and terminated after 30 min by the addition of perchloric acid (24% v/v, 10 µl) to precipitate microsomal protein. The assay internal standard, 4-MUG (10 µl of a 2.5 mm aqueous solution), was added to each sample. Mixtures were vortex mixed for approximately 2 min and subsequently centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min. A 0.1 ml aliquot of the supernatant fraction was transferred to a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube containing 2 m KOH (2 µl) to raise the mixture pH to approximately 3.5. An aliquot (0.04–0.05 ml) of each sample was injected directly on to the h.p.l.c. column.

Variations to this procedure included: (i) Omission of MgCl2 from the incubation mixture, (ii) Activation of microsomes by the addition of the nonionic detergent Brij58. Microsomes were preincubated with Brij58 on ice for 30 min, using a Brij58 to microsomal protein ratio of 0.15 (w/w). This ratio was shown to maximally activate human liver microsomal GAZT formation (data not shown), (iii) Activation of microsomes by addition of the pore-forming peptide, alamethacin (25–100 mg l−1). Microsomes were preincubated with alamethacin on ice for 30 min, (iv) Activation with UDP-NAcG (1 mm), by preincubation with microsomes on ice for 30 min, (v) Addition of the β-glucuronidase inhibitor, d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (8.5 mm), (vi) Phosphate and Tris buffer pH. Incubations were performed using buffers of pH 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.4, 8.0, 8.5 and 9.0 (at a concentration of 0.1 m), (vii) Phosphate buffer concentration. Incubations were performed in buffer over the concentration range 0.02–0.2 mm (at pH 7.4), (viii) Addition of ATP generating system. Incubations were performed in the presence of ATP (4 mm), creatine phosphate (10 mm) and creatine kinase (100 mg l−1) in Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4) and (ix) Addition of GTP (0.1 mm).

Experiments performed to determine the Michaelis constant (Km) and maximal velocity (Vmax) for GAZT formation by human microsomes included at least 8 AZT concentrations in the range 50–4000 µm, at constant UDPGA concentration (10 mm). Similarly, kinetic constants for UDPGA were determined by measuring GAZT formation by human liver microsomes for 8 UDPGA concentrations in the range 100–4000 µm, at constant AZT concentration (5 mm).

Measurement of GAZT formation

The h.p.l.c. used comprised a LC110 solvent delivery system, LC 1200 u.v.-vis variable wavelength detector (both ICI Instruments, Melbourne, Australia) and a BBC Goetz Metrawatt dual pen recorder, and operated at ambient temperature. The instrument was fitted with a Waters Guard-Pak C18 µBondapak precolumn (Waters Associates, Milford, MA, USA) and a Beckman Ultrasphere C8 analytical column (5 µm particle size, 4.6 mm (i.d.) × 25 cm; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA (USA). The mobile phase, phosphate buffer (0.05 m, pH 3.1)-acetonitrile (89 : 11), was delivered at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Column eluant was monitored at 267 nm. Under these conditions, retention times of GAZT, 4-MUG and AZT were 7.3, 15.2 and 16.1 min, respectively.

Five GAZT standards, dissolved in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4), were prepared in the range 5–300 µm and treated in the same manner as incubation samples. Concentrations of GAZT in incubation samples were determined by comparison of GAZT to 4-MUG peak height ratios with those of the standard curve.

Assay validation

Standard curves were linear in the range 5–300 µm (r2 > 0.990), and the coefficient of variation for the slopes of 25 standard curves was 4.7%. Overall assay reproducibility, assessed by measuring GAZT formation in 10 separate incubations of the same batch of pooled human liver microsomes, was 3.7%, 2.1% and 2.5% for added AZT concentrations of 50 µm, 1000 µm and 3000 µm, respectively. The limit of determination for GAZT was 1 µm. Using pooled human liver microsomes, rates of GAZT formation were shown to be linear for incubation times between 15 and 90 min and for microsomal protein concentrations between 0.5 and 3.0 mg ml−1 (data not shown).

Non-specific microsomal binding

Non-specific microsomal binding of AZT to human liver microsomes was investigated by equilibrium dialysis, according to the procedure of McLure et al. [17]. Briefly, one side of the dialysis apparatus contained AZT (100, 1000 or 3000 µm), pooled human liver microsomes (1 mg ml−1, native or activated with Brij58), and phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4), while the other compartment contained phosphate buffer alone. Duplicate measurements were performed for each AZT concentration. The dialysis cell assembly was immersed in a water bath maintained at 37 °C and rotated at 12 rev min−1 for 3 h. The contents of each compartment (1.2 ml) were collected, treated with perchloric acid (0.015 ml of a 24% v/v solution), vortex mixed, and centrifuged (1500 g for 10 min). The supernatant fractions were treated with KOH (1 m, 0.1 ml) to raise the pH to approximately 3.5, and an aliquot (0.05 ml) was injected on to the h.p.l.c. The h.p.l.c. system and conditions were essentially identical to those described previously for the measurement of GAZT, except that the proportion of acetonitrile in the mobile phase was increased to 20% and internal standard (4-MUG) was omitted. Under these conditions, AZT eluted at 6.0 min Standards in the concentration range 50–2000 µm were prepared in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4) and treated in the same manner as dialysis samples. AZT concentrations of dialysis samples were determined by comparison of peak heights with those of the standard curve. Standard curves were linear (r2 > 0.990), and the coefficient of variation for the slopes of four standard curves was 2.8%. Assay reproducibility, assessed by measurement of 10 replicates, was 5.7% and 3.6% for AZT concentrations of 100 µm and 1000 µm, respectively. The limit of determination for AZT was 2.5 µm.

Data analysis

Microsomal kinetic data were model-fitted using EnzFitter (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) to obtain values of apparent Km and Vmax. The choice of model (one or two enzyme Michaelis-Menten, Hill function) was confirmed by F-test and coefficient of determination. Microsomal intrinsic clearance, CLint, was calculated as Vmax/Km (units of µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein) and subsequently scaled to the ‘whole’ liver CLint assuming a liver weight of 1500 g and a microsome yield of 45 mg microsomal protein g-1 of liver [1, 3]. In vivo CLH was then predicted using expressions for the well-stirred, parallel-tube and dispersion models [1, 3–8].

Well Stirred model:

where fu is fraction unbound in blood and QH is liver blood flow, assumed to be 90 l h−1.

Parallel-tube model:

|

Dispersion model:

|

DN, the dispersion number, may be taken as 0.17 [6] and a = (1 + 4.RN.DN)1/2

RN, the efficiency, is given by

The fraction of drug unbound in blood may be evaluated as, fu = fup/RB, where RB is the blood to plasma concentration ratio and fup is the fraction unbound in plasma. For AZT, fup was taken as 0.77 and RB as 0.86 [18]. Taking into account the blood to plasma concentration ratio, the blood AZT CLH by glucuronidation may be calculated from the plasma clearance (see Introduction) as 82 l h−1.

Group data are presented as mean ± s.d.. Correlations and statistical analyses were performed with Instat version 3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc). Group data were analysed by nonparametric anova (Kruskal–Wallis test), with Dunn's multiple comparisons test to detect differences between conditions or models.

Results

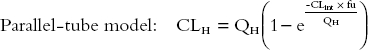

AZT glucuronidation kinetics by native and detergent-activated microsomes from five human livers were characterized in phosphate and Tris buffers (both 0.1 m, pH 7.4). Derived kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1, and representative kinetic plots for each set of experimental conditions are shown in Figure 1. Human liver microsomal AZT glucuronidation kinetics followed single enzyme Michaelis-Menten kinetics for all conditions in all livers. (Experiments with pooled microsomes using substrate concentrations to 10 µm precluded biphasic kinetics or non-Michaelis Menten kinetics.) Derived kinetic constants are similar to values reported previously for the conversion of AZT to GAZT [16, 19].

Table 1.

Kinetic data for zidovudine glucuronidation by native and detergent-activated human liver microsomes in phosphate- and Tris-buffered incubations (0.1 m, pH 7.4)a.

| Microsome treatment | Km (µm) | Vmax (pmol min−1 mg−1) | CLint (µl min−1 mg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native, | 926 ± 197 | 920 ± 280 | 1.04 ± 0.42 |

| phosphate buffered | (682, 1170) | (527, 1268) | (0.53, 1.56) |

| Native, | 1235 ± 219 | 1684 ± 394 | 1.37 ± 0.30 |

| Tris-buffered | (963, 1506) | (1195, 2174) | (1.00, 1.73) |

| Activated (Brij58), | 1011 ± 261 | 3695 ± 954* | 3.66 ± 1.40* |

| phosphate-buffered | (687, 1334) | (2311, 4680) | (1.92, 5.39) |

| Activated (Brij58), | 1390 ± 221 | 5193 ± 907* | 3.79 ± 0.74* |

| Tris-buffered | (1116, 1664) | (4068, 6319) | (2.87, 4.71) |

Data presented as mean ± s.d., with 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis, for microsomes from 5 human livers.

P < 0.05 compared with values for phosphate- and Tris- buffered native microsomes.

Figure 1.

Representative Eadie-Hofstee plots for the conversion of AZT to GAZT using microsomes from a single liver. Incubations were performed at pH 7.4 and a buffer concentration of 0.1 m, with other conditions as described in Microsomal incubations. Panel a, native microsomes–phosphate buffer; Panel b, Brij58 activated microsomes–phosphate buffer; Panel c, native microsomes–Tris buffer; Panel d, Brij58 activated microsomes–Tris buffer.

Differences in mean apparent Km and Vmax values determined from Tris buffered incubations and phosphate buffered incubations using the corresponding activation conditions (i.e. native vs native, activated vs activated) were not statistically significant (Table 1). Detergent activation of Tris and phosphate buffered microsomes increased Vmax 3.1- and 3.8-fold (P < 0.05), respectively, without changing apparent Km (Table 1). For detergent activated microsomes, similar relative differences in apparent Km and Vmax for Tris buffered microsomes compared to phosphate buffered microsomes resulted in similar values of microsomal CLint for the two buffer types. The mean UDPGA apparent Km values for detergent activated microsomes (n = 5 livers) in phosphate and Tris buffered incubations were 797 ± 62 µm (95% CI: 710–841 µm) and 766 ± 160 µm (95% CI: 638–1005 µm), respectively (data not shown).

Microsomal CLint values determined for GAZT formation by native and detergent activated microsomes in Tris and phosphate buffered incubations were extrapolated to blood AZT glucuronidation hepatic clearances using the expressions for the well-stirred, parallel tube and dispersion models, as described in Data analysis. In vivo CLH values determined using these models are summarized in Table 2. The extrapolated mean in vitro CLint values derived for native and detergent activated microsomes underestimated AZT glucuronidation clearance in vivo (viz 82 l h−1, see Data analysis) by 17–23-fold and 6.5–7.3-fold, respectively.

Table 2.

Predicted zidovudine glucuronidation hepatic clearances derived from the well-stirred, parallel tube and dispersion modelsa.

| Predicted CLH(l h−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Microsome treatment | Well-stirred | Parallel tube | Dispersion |

| Native, | 3.61 ± 1.38 | 3.70 ± 1.44 | 3.67 ± 1.42 |

| phosphate-buffered | (1.90, 5.32) | (1.91, 5.48) | (1.90, 5.43) |

| Native, Tris-buffered | 4.69 ± 0.96 | 4.82 ± 1.01 | 4.78 ± 1.00 |

| (3.50, 5.88) | (3.56, 6.07) | (3.54, 6.02) | |

| Activated (Brij58), | 11.27 ± 4.06* | 12.24 ± 4.37* | 11.98 ± 4.26* |

| phosphate-buffered | (6.53, 16.34) | (6.81, 16.66) | (6.69, 16.47) |

| Activated (Brij58), | 11.88 ± 2.00* | 12.71 ± 2.29* | 12.46 ± 2.20* |

| Tris-buffered | (9.54, 15.20) | (9.86, 15.59) | (9.65, 15.36) |

Data presented as mean ± s.d., with 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis, for microsomes from 5 human livers.

P < 0.05 compared with values for phosphate- and Tris-buffered native microsomes.

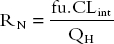

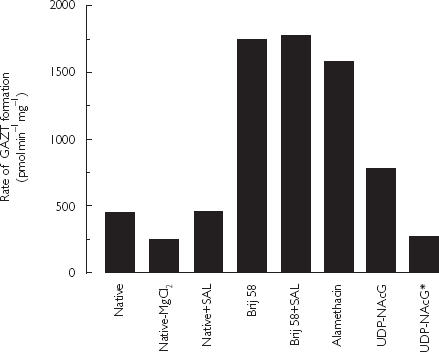

Given the poor predicability of microsomal CLint for estimating in vivo CLH, factors potentially altering human liver microsomal AZT glucuronidation kinetics were investigated further. Unless stated otherwise, the influence of factors known to influence glucuronide formation in vitro were investigated using pooled liver microsomes (1 mg ml−1), AZT (1 mm; the approximate apparent Km), MgCl2 (4 mm), and UDPGA (10 mm) in phosphate buffered (0.1 m, pH 7.4) incubations. The comparative effects of known activators of UGT and of the β-glucuronidase inhibitor d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone on AZT glucuronidation are shown in Figure 2. Omission of MgCl2 from incubations decreased GAZT formation by approximately 50%. Detergent (Brij58, 0.15 w/w) produced slightly greater activation than alamethacin (3.9-fold vs 3.5-fold). The extent of activation by alamethacin was essentially constant over the concentration range 25–100 mg l−1 (data not shown). GAZT formation was activated less than 2-fold by UDP-NAcG, and reduction of the UDPGA concentration to 0.25 mm reversed the effect of UDP-NAcG. Addition of d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone to incubations did not alter the rate of microsomal AZT glucuronidation.

Figure 2.

Effects of incubation components on the rate of AZT glucuronidation by pooled human liver microsomes. Incubations were performed in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4) in the presence of AZT (1 mm), UDPGA (10 mm) and, unless indicated, MgCl2 (4 mm). Abbreviations: Native = native microsomes; SAL, d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (8.5 mm); Brij58, microsomes activated with Brij58 (0.15 w/w); Alamethacin, microsomes activated with alamethacin (50 mg l−1); UDP-NAcG, microsomes activated with UDP-NAcG (1 mm); UDP-NAcG*, microsomes activated with UDP-NAcG (1 mm) and UDPGA concentration reduced to 0.25 mm.

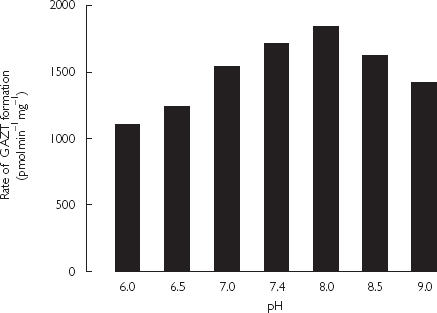

The effects of incubation pH were assessed for detergent activated microsomes in both phosphate and Tris buffers (0.1 m). Data for phosphate buffered microsomes are shown in Figure 3; an identical trend was observed using Tris buffer. The rate of GAZT formation increased between pH 6.0 and 8.0, and declined thereafter. However, the rates of GAZT formation at pH 7.4 and 8.0 differed by only 7%. Effects of an ATP generating system and added GTP on GAZT formation were investigated in Tris buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4), with and without detergent or alamethacin (50 mg l−1) activation. The respective rates of GAZT formation in control, ATP-containing and GTP-containing incubations were: 713, 627 and 769 pmol min−1 mg microsomal protein−1 using native microsomes; 2395, 2443 and 2454 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein using detergent activated microsomes; and 2109, 1904 and 2265 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein using alamethacin activated microsomes.

Figure 3.

Effects of phosphate buffer (0.1 m) pH on the rate of AZT glucuronidation by Brij58 activated pooled human liver microsomes (1 mg ml−1). Incubations contained AZT (1 mm), UDPGA (10 mm) and MgCl2 (4 mm).

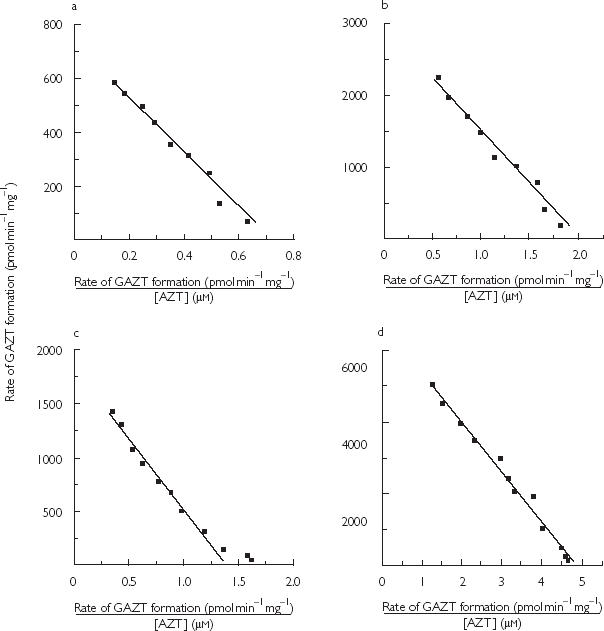

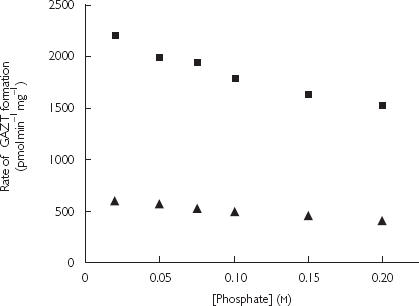

The rate of GAZT formation declined with increasing phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) concentration in the range 0.02–0.2 mm, with both native and detergent activated microsomes (Figure 4). To investigate the mechanism of the effect of buffer concentration on GAZT formation, the kinetics of AZT glucuronidation by native and detergent activated microsomes were determined at phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) concentrations of 0.02 and 0.1 m (Table 3). Apparent Km decreased while Vmax remained unchanged at the lower buffer concentration. The microsomal CLint values determined for microsomal incubations performed in 0.02 m phosphate were 62–68% higher than values determined using 0.1 m phosphate buffer.

Figure 4.

Effect of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) concentration on the rate of AZT glucuronidation by pooled human liver microsomes. Native (▴) refers to native microsomes, and Activated (▪) to Brij58 treated microsomes (0.15 w/w). Incubations contained AZT (1 mm), UDPGA (10 mm) and MgCl2 (4 mm).

Table 3.

Kinetic data for zidovudine glucuronidation by native and detergent activated pooled human liver microsomes in phosphate buffer of concentration 0.02 m.

| Microsome treatment | Km (µm) | Vmax (pmol min−1 mg−1) | CLint (µl min−1 mg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native, phosphate buffer 0.1 m | 890 | 957 | 1.08 |

| Native, phosphate buffer 0.02 m | 551 | 999 | 1.81 |

| Activated (Brij58), phosphate buffer 0.1 m | 1018 | 3708 | 3.64 |

| Activated (Brij58), phosphate buffer 0.02 m | 672 | 3960 | 5.89 |

AZT did not bind nonspecifically to human liver microsomes. For added AZT concentrations of 100, 1000 and 3000 µm, ratios of AZT in the buffer and microsome compartments of the equilibrium dialysis apparatus were 0.97, 1.08 and 0.96, respectively, using native microsomes, and 1.03, 1.10 and 0.99, respectively, using detergent activated microsomes.

Discussion

Despite the widespread use of in vitro-in vivo scaling for drugs eliminated by CYP [1, 3, 7, 8], little attention has been paid to the validity of scaling in vitro CLint to hepatic clearance in vivo for drugs metabolized by UGT. The initial aim of the work described here was to assess whether microsomal CLint for the model glucuronidated drug AZT predicted CLH in vivo using mathematical models of hepatic drug clearance. Since microsomal incubation conditions for the measurement of drug glucuronidation kinetic parameters interchangeably use phosphate and Tris buffers, with or without activation, kinetic constants determined under these various reaction conditions were compared. Mean microsomal CLint for AZT glucuronidation varied 3.6-fold for the different incubation conditions. Depending on the conditions and mathematical model of hepatic clearance employed, predicted CLH underestimated AZT glucuronidation clearance by 6.5- to 23-fold. Although other factors were subsequently shown to influence AZT glucuronidation in vitro, it was apparent that no set of conditions could be developed that gave a microsomal CLint high enough to predict metabolic clearance in vivo.

The use of phosphate or Tris buffer in microsomal incubations is known to variably affect CYP3A activities [9]. Although both apparent Km and Vmax for AZT glucuronidation tended to be higher for incubations buffered with Tris compared with phosphate (with and without detergent activation), differences were not statistically significant. Moreover, Km and Vmax tended to increase in parallel resulting in similar values of CLint for the two buffer types. As expected from studies with other glucuronidated substrates (for example [20]), the nonionic detergent Brij58 increased Vmax approximately 3- to 4-fold. In both the presence and absence of detergent, the rate of AZT glucuronidation increased with decreasing phosphate concentration in the range 0.2-0.02 m. This effect was due to a lowering of apparent Km rather than an increase in Vmax. Although lowering the phosphate buffer concentration resulted in an approximately 60% increase in the microsomal CLint obtained for detergent activated microsomes (Table 3), the extrapolated CLH still underestimated AZT glucuronidation clearance by a factor of 4.3–4.8. (CLH values obtained using the well-stirred and parallel tube models were 17.26 and 19.01 l h−1, respectively.) Interestingly, the trend observed for the effect of phosphate concentration on AZT glucuronidation is opposite to that observed for most CYP-catalysed reactions, where activity tends to increase in the buffer concentration range 0.01–0.2 m [9]. In the case of CYP, it has been proposed that this effect may arise from changes in protein conformation [21].

No other treatment increased rates of AZT glucuronidation more than Brij58. The pore-forming agent alamethacin activated AZT glucuronidation by 3.5-fold, which is similar to observations with other glucuronidated substrates [22]. UDP-NAcG, an endogenous activator of UGT [11], increased AZT glucuronidation less than 2-fold. It has been suggested that effects of UDP-NAcG are maximal at physiological concentrations of cofactor (UDPGA) [23], but rates of AZT glucuronidation decreased in the presence of UDP-NAcG (1 mm) and UDPGA (0.25 mm) compared with conditions where the cofactor concentration (viz 10 mm) was not rate-limiting. Omission of MgCl2 decreased the rate of AZT glucuronidation, confirming the stimulatory effect of Mg2+ on human liver microsomal UGT. A dependence of AZT glucuronidation rate on incubation pH was also confirmed, although activity was near maximal at pH 7.4, which is most commonly employed for investigations of microsomal xenobiotic glucuronidation (at least for those substrates forming an ether glucuronide). Significant β-glucuronidase activity has been reported for human liver microsomes [24], and hydrolysis of product would result in underestimation of the rate of AZT glucuronidation. However, addition of d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone was without effect on AZT glucuronide formation.

Available evidence suggests that the UGT active site may be located on the lumenal side of the microsomal membrane and that cofactor availability may be dependent on carrier mediated transport [25]. There are previous reports of stimulation of UGT activity by ATP and GTP [11, 26], although effects are variable and may involve mechanisms other than facilitation of active transport [11]. In this work, the rate of AZT glucuronidation was unaffected by both ATP and GTP. Moreover, the pore-forming peptide alamethacin, which apparently facilitates free diffusion of substrate and product between the UGT active site and the cytosol without affecting enzyme activity [22], increased AZT glucuronidation only to the same extent as detergent activation.

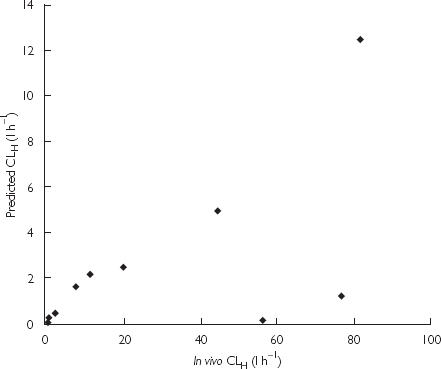

Given the poor correspondence between the known clearance of AZT by glucuronidation and the CLH predicted from in vitro kinetic data, in vitro-in vivo comparisons were additionally performed for the glucuronidated drugs naloxone, propofol, morphine, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, paracetamol, amitriptyline, lamotrigine, clofibric acid, valproic acid and naproxen, using published data (Table 4). Blood drug clearances by glucuronidation for these drugs are in the range 0.20–77 l h−1. In vitro kinetic data used to calculate CLint and CLH were obtained using microsomal incubation conditions similar to those employed in this work; incubations were performed in phosphate or Tris buffer (0.1 m, pH 6.8–7.5) with activated (detergent or sonication) human liver microsomes. It is apparent from Table 4 and Figure 5 that predicted CLH underestimated blood clearance by glucuronidation for all compounds. Ratios of predicted CLH to in vivo clearance ranged from 0.003 (propofol) to 0.80 (clofibric acid). Interestingly, predicted CLH and clearance in vivo were significantly correlated (Figure 5: P = 0.042; r = 0.62; slope = 0.078, 95% CI 0.003, 0.140). Exclusion of the data for naloxone and propofol, which show the greatest discrepancies, greatly improved the correlation (P < 0.0001; r = 0.98; slope = 0.143, 95% CI 0.124, 0.163). Mistry and Houston [28] reported similar findings in rat for morphine, naloxone and buprenorphine, where hepatic microsomal CLint values were approximately 20–to 30-fold lower than their in vivo counterparts but rank orders were the same. Clearly, the approaches adopted currently for the scaling of in vitro kinetic data do not accurately predict in vivo CLH for drugs eliminated by glucuronidation. The possibility remains, however, that assessment of a larger data set may validate the use of a scaling factor for the extrapolation of in vitro CLint.

Table 4.

Comparison of in vivo blood drug clearances by glucuronidation and hepatic clearances predicted from published in vitro kinetic dataa.

| Drug | In vivo blood clearance by glucuronidationa,b (l h−1) | Hepatic clearance by glucuronidation predicted by dispersion modelc,d (l h−1) | References for in vitro and in vivo data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zidovudine | 82.0 | 12.46 | This study, 12–14 |

| Naloxone | 76.72 | 1.20 | 31–33 |

| Propofol | 56.28 | 0.16 | 33–36 |

| Morphine (3- and 6-glucuronidation) | 44.40 | 4.92 | 33, 37, 38 |

| DMXAAe | 19.75 | 2.49 | 39–41 |

| Paracetamol | 11.21 | 2.19 | 42–46 |

| Amitriptyline | 7.40 | 1.63 | 47–49 |

| Lamotrigine | 2.08 | 0.45 | 50–52 |

| Clofibric acid | 0.35 | 0.28 | 53–55 |

| Naproxen | 0.26 | 0.04 | 33, 56 |

| Valproic acid | 0.20 | 0.09 | 33, 57 |

Clearance by glucuronidation was determined as CLs,blood × fgluc, where fgluc is the fractional urinary recovery of glucuronide. For the low hepatic clearance drugs clofibric acid, naproxen, and valproic acid, CL/F was used due to the unavailability of CLs values.

CLs,blood values were available for propofol and amitriptyline. RB values reported for zidovudine, morphine, DMXAA and paracetamol were used to calculate CLs blood as: CLs,blood = CLs,plasma/RB. RB was taken as 1 for naloxone and lamotrigine, and 0.7 for clofibric acid, naproxen, and valproic acid [58].

Literature values of Km and Vmax were all determined using activated (detergent or sonication) human liver microsomes.

Predicted CLH was determined using the dispersion model (Data analysis). Literature values of RB were used to calculate fu from fu,p, as described in Data analysis. Where RB could not be obtained from the literature (naloxone, lamotrigine, clofibric acid, naproxen, valproic acid), a value of 1 or 0.7 was assumed (see footnote b).

5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the in vivo blood clearances by glucuronidation and hepatic clearances predicted from published in vitro kinetic data for the drugs listed in Table 4.

Taken together, these data suggest that the CLint determined from microsomal kinetic studies underestimates in vivo CLint, or perhaps extrahepatic glucuronidation is a major contributor to drug elimination in vivo. The latter seems unlikely, at least with respect to renal AZT glucuronidation. Assuming kidney weight of 300 g and a renal microsome yield of 6 mg g−1 [28], the ‘whole’ kidney CLint for AZT glucuronidation determined from published kinetic constants [19] is 0.017 l h−1. The corresponding ‘whole’ liver CLint calculated from kinetic constants derived in the present work, using the same incubation conditions (native microsomes, Tris buffer), is 5.55 l h−1.

The possibility remains that the assumptions underpinning the mathematical models of CLH used throughout this work are not applicable to glucuronidation. As noted previously, UGT is believed to be localized on the lumenal side of the microsomal membrane and this may give rise to diffusional ‘barriers’. Another potential confounding factor, nonspecific microsomal binding of substrate which may result in underestimation of CLH [17, 29], was discounted here for AZT and is also negligible for morphine (Stone and Miners, unpublished data). In addition, nonspecific binding may normally also be discounted for acidic drugs, such as naproxen, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, valproic acid and clofibric acid [17]. However, extensive binding to the microsomal membrane is known to occur for amitriptyline [17], and cannot be excluded for other bases listed in Table 4 (naloxone, lamotrigine) or for the highly lipophilic compound propofol.

In conclusion, it has been confirmed that the kinetic parameters for AZT glucuronidation by human liver microsomes are markedly dependent on incubation incubations. Burchell et al. [34] have previously noted that investigations of UGT activity in vitro employ widely differing reaction conditions. The present work highlights the need for standardization of incubation conditions if there is to be meaningful interlaboratory comparison of drug glucuronidation kinetic data. It was also shown that none of the reaction conditions investigated predicted AZT hepatic clearance by glucuronidation in vivo. Calculations based on published kinetic data further demonstrated that extrapolated hepatic clearance invariably underestimated in vivo clearance by glucuronidation. Importantly, known high hepatic clearance drugs were predicted to have hepatic clearances in the ‘low’ range. Although a statistically significant correlation may exist between predicted and actual hepatic clearance, caution should be exercised when extrapolating in vitro kinetic data to the in vivo situation for drugs eliminated by glucuronidation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- 1.Obach RS, Baxter JG, Liston TE, et al. The prediction of human pharmacokinetic parameters from preclinical and in vitro metabolism data. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:46–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miners JO, Veronese ME, Birkett DJ. In vitro approaches for the preclinical prediction of human drug metabolism. Ann Reports Med Chem. 1994;29:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houston JB. Utility of in vitro drug metabolism data in predicting in vivo metabolic clearance. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:1469–1479. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson GR, Shand DG. A physiological approach to hepatic drug clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975;18:377–390. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975184377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang KS, Rowland M. Hepatic clearance of drugs. I. Theoretical considerations of a ‘well-stirred’ model and a ‘parallel tube’ model. Influence of hepatic blood flow, plasma and blood cell binding, and the hepatocellular enzymatic activity on hepatic drug clearance. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1977;5:625–653. doi: 10.1007/BF01059688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts MS, Rowland M. Correlation between in vitro microsomal enzyme activity and whole organ hepatic elimination kinetics: analysis with a dispersion model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1986;38:177–181. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1986.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito K, Iwatsubo T, Kanamitsu S, et al. Quantitative prediction of in vivo drug clearance and drug interactions from in vitro data on metabolism, together with binding and transport. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:461–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwatsubo T, Hirota N, Ooie T, et al. Prediction of in vivo drug metabolism in the human liver from in vitro metabolism data. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;73:147–171. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maenpaa J, Hall SD, Ring BJ, Strom SC, Wrighton SA. Human cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) mediated midazolam metabolism. the effect of assay conditions and regioselective stimulation by α–naphthoflavone, terfenadine and testosterone. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:137–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miners JO, Mackenzie PI. Drug glucuronidation in humans. Pharmacol Ther. 1991;51:347–369. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90065-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutton GJ. Glucuronidation of Drugs and Other Compounds. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1980. pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stagg MP, Cretton EM, Kidd L, Diasio RB, Sommadossi J-P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of 3′-azido3′-deoxythymidine (zidovudine) and catabolites with formation of a toxic catabolite, 3′-amino-3′-deoxythymidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:668–676. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klecker RW, Collins JM, Yarchoan R, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine: a novel pyrimidine analog with potential application for the treatment of patients with AIDS an related diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;41:407–412. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum MR, Liao SHT, de Miranda P. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of zidovudine in humans. Am J Med. 1988;85(Suppl 2A):189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robson RA, Matthews AP, Miners JO, et al. Characterisation of theophylline metabolism by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sim SM, Back DJ, Breckenridge AM. The effect of various drugs on the glucuronidation of zidovudine (azidothymidine; AZT) by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLure JA, Miners JO, Birkett DJ. Nonspecific binding of drugs to human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:453–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luzier A, Morse GD. Intravascular distribution of zidovudine: role of plasma proteins and whole blood components. Antiviral Res. 1993;21:267–280. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90032-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe JL, Back DJ, Colbert J. Extrahepatic metabolism of zidovudine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33:190–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miners JO, Lillywhite KJ, Matthews AP, Jones ME, Birkett DJ. Kinetic and inhibitor studies of 4-methylumbelliferone and 1-naphthol glucuronidation in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:665–671. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun C-H, Song M, Ahn T, Kim H. Conformational change of cytochrome P4501A2 induced by sodium chloride. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31312–31316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher MB, Campanale K, Ackermann BL, Vandenbranden M, Wrighton SA. In vitro glucuronidation using human liver microsomes and the pore-forming peptide alamethacin. Drug Metab Disp. 2000;28:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock KW, White INH. UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase in perfused rat liver and in microsomes: Influence of phenobarbital and 3-methylcholanthrene. Eur J Biochem. 1974;46:451–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunelle FM, Verbeeck RK. Glucuronidation of diflunisal in liver and kidney microsomes of rat and man. Xenobiotica. 1996;26:123–131. doi: 10.3109/00498259609046694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radominska-Pandya A, Czernik PJ, Little JM, Battaglia E, Mackenzie PI. Structural and functional studies of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Rev. 1999;31:817–899. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100101944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blankaert N. Guanosine 5′-phosphate modulates uridine-5′-diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase activities in rat liver microsomes. Gastroenterol. 1988;94:A526. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mistry M, Houston JB. Glucuronidation in vitro and in vivo. Comparison of intestinal and hepatic conjugation of morphine, naloxone and buprenorphine. Drug Metab Disp. 1987;15:710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowalgaha K, Miners JO. The glucuronidation of mycophenolic acid by human liver, kidney and jejunum microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:605–609. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obach RS. Nonspecific binding to microsomes. Impact on scale-up of in vitro intrinsic clearance to hepatic clearance as assessed through examination of warfarin, imipramine and propranolol. Drug Metab Disp. 1997;42:1359–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burchell B, Brierley CH, Rance D. Specificity of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and xenobiotic glucuronidation. Life Sci. 1995;57:1819–1131. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02073-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aitkenhead AR, Derbyshire DR, Pinnock DR, Achola K, Smith G. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous naloxone in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiol. 1984;61:A381. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asali LA, Brown KF. Naloxone protein binding in adult and foetal liver. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;27:459–463. doi: 10.1007/BF00549595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soars MG, Riley RJ, Findlay KAB, Coffey MJ, Burchell B. Evidence for significant differences in microsomal drug glucuronidation by canine and human liver and kidney. Drug Metab Disp. 2001;29:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simons PJ, Cockshott ID, Douglas EJ, Gordon EA, Hopkins K, Rowland M. Disposition in male volunteers of a subanaesthetic intravenous dose of an oil in water emulsion of 14C-propofol. Xenobiotica. 1988;18:429–440. doi: 10.3109/00498258809041679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gepts E, Camu F, Cockshott ID, Douglas EJ. Disposition of propofol administered as constant rate intravenous infusions in humans. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:1256–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Servin F, Desmonts JM, Haberer JP, Cockshott ID, Plummer GF, Farinotti R. Pharmacokinetics and protein binding of propofol in patients with cirrhosis. Anesthesiol. 1988;69:887–891. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasselstrom J, Sawe J. Morphine pharmacokinetics and metabolism in humans: Enterohepatic cycling and relative contribution of metabolites to active opioid concentrations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;24:344–354. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milne RW, Nation RL, Somogyi AA. The disposition of morphine and its 3- and 6-glucuronide metabolites in humans and animals, and the importance of metabolites to the pharmacological effects of morphine. Drug Metab Rev. 1996;28:345–472. doi: 10.3109/03602539608994011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou S, Chin R, Kestell P, Tingle MD, Paxton JW. Effects of anticancer drugs on the metabolism of the anticancer drug 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:129–136. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jameson MB, Thomson PI, Baguley BC, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA), a novel antivascular agent. Proc Annu Meet Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:705. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miners JO, Valente L, Lillywhite KJ, et al. Preclinical prediction of factors influencing the disposition of 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, a new anticancer drug. Cancer Res. 1997;57:284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rawlins MD, Henderson DB, Hijab AR. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol (acetaminophen) after intravenous and oral administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;11:283–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00607678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miners JO, Attwood J, Birkett DJ. Influence of sex and oral contraceptive steroids on paracetamol metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;16:503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamali F, Fry JR, Bell GD. Salivary secretion of paracetamol in man. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1986;39:150–152. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb06967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gwilt JR, Robertson A, Chesney EW. Determination of blood and other tissue concentrations of paracetamol in dog and man. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1983;15:440–444. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1963.tb12811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miners JO, Lillywhite KJ, Yoovathaworn K, Pongmarutai M, Birkett DJ. Characterization of paracetamol UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:595–600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz P, Dick P, Blaschke TF, Hollister L. Discrepancies between pharmacokinetic studies of amitriptyline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10:257–268. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breyer-Pfaff U, Pfandel B, Nill K, et al. Enantioselective amitriptyline metabolism in patients phenotyped for two cytochrome P450 isozymes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;52:350–358. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breyer-Pfaff U, Fischer D, Winne D. Biphasic kinetics of quaternary ammonium glucuronide formation from amitriptyline and diphenhydramine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Disp. 1997;25:340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuen WC, Peck AW. Lamotrigine pharmacokinetics: oral and i.v. infusion in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:242P. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rambeck B, Wolf P. Lamotrigine clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25:433–443. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199325060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magdalou J, Herber R, Bidault R, Siest G. In vitro glucuronidation of a novel antiepileptic drug, lamotrigine, by human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miners JO, Robson RA, Birkett DJ. Gender and oral contraceptive steroids as determinants of drug glucuronidation; effects on clofibric acid elimination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;18:240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emudianughe TS, Caldwell J, Sinclair KA, Smith RL. Species differences in the metabolic conjugation of clofibric acid and clofibrate in laboratory animals and man. Drug Metab Disp. 1983;11:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dragacci S, Hamar-Hansen C, Fournel-Gigleux S, Lafaurie C, Magdalou J, Siest G. Comparative study of clofibric acid and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:3923–3927. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vree TB, Van Den Biggelaar-Martea M, Verwy-Van Wissen CPWGM, Vree ML, Guelen PJM. The pharmacokinetics of naproxen, its metabolite O-desmethylnaproxen, and their acyl glucuronides in humans. Effects of cimetidine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Addison RS, Parker-Scott SL, Hooper WD, Dickinson RG. Effect of naproxen co-administration on valproate disposition. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2000;21:235–242. doi: 10.1002/bdd.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carlile DJ, Hakooz N, Bayliss MK, Houston JB. Microsomal prediction of in vivo clearance of CYP2C9 substrates in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:625–636. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]