Abstract

Aims

Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg 24 h−1) is recognized to be independently associated with renal and cardiovascular risk. Antihypertensives may lower microalbuminuria. We questioned whether the use of different antihypertensive drug classes in general practice influences microalbuminuria as related to blood pressure in nondiabetic subjects.

Methods

To study this, we used the data from 6836 subjects of an on-going population based study, focused on the meaning of microalbuminuria (PREVEND). Odds ratios, adjusted for age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol level, smoking and the use of other antihypertensive or cardiovascular drugs, were calculated to determine the association of drug groups with microalbuminuria. Influence of antihypertensives on the relation between blood pressure and (log) urinary albumin excretion was determined by comparing linear regression lines.

Results

Microalbuminuria was significantly associated with the use of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (odds ratio: 1.76 [1.22–2.54]), but not with other antihypertensive drug groups. The linear regression line of the relation between blood pressure and (log) urinary albumin excretion was significantly steeper (P = 0.0047) for users of calcium channel blockers, but not for other antihypertensives, compared with subjects using no antihypertensive. Users of a combination of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and diuretics however, had a less steep regression line (P = 0.037).

Conclusions

This study suggests a disadvantageous effect of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers on microalbuminuria compared with other antihypertensive drug groups. Thus, if microalbuminuria is causally related to an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, dihydropyridines do not seem to be agents of choice to lower blood pressure. Furthermore, the combination of renin-angiotensin system inhibition and diuretics seems to act synergistically.

Keywords: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antihypertensive treatment, calcium channel blockers, hypertension, microalbuminuria

Introduction

Microalbuminuria (defined as a urinary albumin excretion of 30–300 mg 24 h−1) is recognized to be independently associated with renal and cardiovascular risk not only in diabetics but also in the hypertensives [1–3]. Microalbuminuria can be found in diabetic populations (prevalence: 10–30% [4–6]), in hypertensive populations (5–25% [5–8]), but also in nondiabetic, nonhypertensive populations (5–10% [6, 9]).

Several classes of drugs, that have been shown to have beneficial cardiovascular effects, such as antihypertensives, lower microalbuminuria [7, 10–13]. The clinical significance of this effect is unknown. Clinical trials have demonstrated different antihypertensive drug classes to vary in their proteinuria- and microalbuminuria-lowering effects. Meta-analyses have shown that the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are superior to other antihypertensives in lowering proteinuria and also microalbuminuria [7, 10, 12, 13]. Later angiotensin II (Ang II) antagonists have been found to be equally effective in this regard as the ACE inhibitors [7, 14]. However, there is disagreement about the calcium channel blockers (CCB), sometimes they are found to be more [10] and sometimes less effective [12].

Two mechanisms are suggested by which antihypertensives can lower urinary albumin excretion. First, antihypertensives lower systemic blood pressure and thus also reduce intraglomerular pressure and thereby urinary albumin excretion. This is supported by the correlation between arterial pressure and urinary albumin excretion [8, 15, 16]. Second, some drugs influence intraglomerular pressure in addition to lowering blood pressure. Indeed, the superiority of ACE inhibitors and Ang II antagonists in lowering microalbuminuria is explained by their ability to lower intraglomerular pressure. CCBs on the other hand, give dilatation of the afferent arterioles, which, if coupled to a high systemic blood pressure, could result in high intraglomerular pressure.

We questioned whether the use of different cardiovascular, and in particular antihypertensive drugs, influence urinary albumin excretion as related to blood pressure in nondiabetic subjects. A difference in lowering urinary albumin excretion may have impact on choosing a specific antihypertensive in general practice.

Methods

Study population and design

We used the data of the PREVEND cohort, consisting of 8592 subjects, aged 28–75 years in the city of Groningen, the Netherlands (for details see [17]). For this analysis we excluded diabetics and pregnant subjects. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants attending the outpatient clinic gave written informed consent.

The participants filled in a questionnaire, from which information was gathered on tobacco use and on medical treatment for hypertension, hyperlipidemia and/or diabetes. Blood pressure was measured at two outpatient visits, in supine position at the right arm every minute for 10 min with an automatic Dinamap XL Model 9300 series device. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were calculated as the mean of the last two measurements of both visits. At the second visit fasting blood samples were taken for direct measurement of glucose and cholesterol. The subjects also handed in two 24 h urine samples at the second visit.

Plasma glucose and serum cholesterol were measured with dry chemistry (Kodak Ectachem). Urinary albumin concentration was determined by nephelometry (Dade Behring diagnostics) with a threshold of 2.3 mg l−1 and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of less than 4.3% and 4.4%, respectively. Leucocyte and erythrocyte counts of the urine were determined by urine sticks. Subjects were excluded for analysis in case of erythrocyturia >50 µl−1, leucocyturia >75 µl−1, or leucocyturia=75 µl−1 and erythrocyturia >5 µl−1.

Definitions

Microalbuminuria was defined as a urinary albumin excretion of 30–300 mg 24 h−1, measured as the mean of two 24 h urine collections. A urinary albumin excretion >300 mg 24 h−1 was defined as macroalbuminuria. Diabetes was defined as having a fasting glucose ≥7.8 mmol l−1, a nonfasting glucose ≥11.1 mmol l−1 or the use of antidiabetic medication. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as 2/3 diastolic blood pressure+1/3 systolic blood pressure. Subjects were classified as smokers when they reported current smoking or having stopped smoking less than 1 year ago; otherwise they were classified as nonsmokers.

Pharmacy records

Pharmacy records were collected at community pharmacies. Since Dutch patients usually register at one community pharmacy, using pharmacy records gives an almost complete view of prescribed drugs [18]. The pharmacy data contain, among other things, the name of the drug, the number of units dispensed, the prescribed daily dose, the date the drugs were collected and the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) code of the drug [19]. In the year preceding the baseline investigation with the urine collections (index year), it was determined if subjects were dispensed cardiovascular drugs; drugs were classified using the ATC code. A subject was considered using a drug if the subject had at least one prescription for that drug in the index year. A combination of drug groups consists of fixed combinations as well as the use of separate preparations of those drug groups.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS 9.0. Data are reported as mean with standard deviation. Differences between continuous variables were tested by use of Student's t-test. Differences in proportions were tested using χ2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, all P values are two-tailed.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the association of the use of cardiovascular drug groups and microalbuminuria. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated as an approximation of relative risk. The relation between blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion in the nondiabetic population (normo-, micro- and macroalbuminurics) was examined using linear regression. The influence of different antihypertensive drug groups was determined by comparing the slope of the regression lines for the different groups with the line for subjects not using antihypertensives. If subjects use more than one drug group, they contribute to more than one regression line, thus prohibiting a comparison between groups.

Results

Subjects were excluded when they had erythrocyturia or leucocyturia (n = 451), were diabetic (n = 359) and when no pharmacy data could be collected (n = 946), leaving 6836 subjects for analysis. For the calculation of associations with microalbuminuria, a further 79 subjects with macroalbuminuria were excluded.

The subject characteristics according to urinary albumin excretion are shown in Table 1. Both micro- and macroalbuminuric subjects were older, more often male and had higher blood pressure and cholesterol levels as compared with normoalbuminurics. Furthermore, micro- and macroalbuminurics used significantly more cardiovascular drugs.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Normoalbuminuria (0–30 mg/24 h) | Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/24 h) | Macroalbuminuria (> 300 mg/24 h) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 5926 | 831 | 79 |

| Age (years) | 47.9 (12.2) | 55.7 (12.3)* | 57.8 (11.9)* |

| Sex (% men) | 48.4 | 65.1* | 68.4* |

| MAP (mmHg) | 90.7 (11.5) | 100.4 (14.3)* | 104.7 (13.1)* |

| Cholesterol (mmol l−1) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.1)* | 6.0 (1.3)* |

| Smoking | 37.8 | 39.3 | 33.3 |

| Cardiovascular drug use | |||

| No | 83 | 67 | 54 |

| 1 drug group | 9 | 13† | 13† |

| 2 drug groups | 4 | 9 | 20 |

| ≥3 drug groups | 4 | 11 | 13 |

Continuous values are reported as means (s.d.), categorical values as percentages, MAP=mean arterial pressure.

P < 0.005 vs normoalbuminuria.

Prevalence distribution for micro- and macroalbuminuria significantly (P < 0.05) different from normoalbuminuria.

Table 2 shows the number of users and crude and adjusted odds ratios for the nonantihypertensive cardiovascular drugs. The use of all these drug classes was significantly associated with microalbuminuria, after adjustment all groups but antiarrhythmics remained associated with microalbuminuria.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for microalbuminuria (MA; 30–300 mg/24 h): cardiovascular drugs.

| Number of users | OR crude | OR adjusted† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug group | No MA | MA | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| Antiarrhythmics | 14 | 8 | 4.10 (1.72, 9.81)* | 2.24 (0.88, 5.69) |

| Anticholesterolaemic agents | 219 | 77 | 2.66 (2.03, 3.49)* | 1.94 (1.46, 2.59)* |

| Antithrombotics | 271 | 111 | 3.22 (2.55, 4.07)* | 1.98 (1.53, 2.56)* |

| Cardiac glycosides | 22 | 17 | 5.60 (2.96, 10.60)* | 3.10 (1.58, 6.10)* |

| Nitrates | 93 | 31 | 2.43 (1.61, 3.67)* | 1.58 (1.02, 2.45)* |

Significant (P < 0.05).

Adjusted for age, sex, mean arterial pressure, cholesterol level and smoking.

In Table 3 crude and adjusted odds ratios are shown for different antihypertensive drug groups. All drug groups had a significant crude OR. We adjusted these associations for age, sex, MAP, cholesterol level, smoking, use of other antihypertensives and use of at least one other cardiovascular drug, thus correcting for comedication and comorbidity. After this correction, only CCB users showed a significant risk of having microalbuminuria. The various subgroups of diuretics and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors yielded similar results. Analysis of the different subclasses of CCBs however, revealed that only dihydropyridine CCBs were associated with microalbuminuria while the OR of nondihydropyridine CCBs became insignificant.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for microalbuminuria (MA; 30–300 mg/24 h): antihypertensive drugs.

| Number of users | OR crude | OR adjusted† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug group | No MA | MA | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| β-adrenoceptor blockers | 426 | 110 | 1.97 (1.58, 2.46)* | 1.01 (0.78, 1.30) |

| α-adrenoceptor blockers | 16 | 9 | 4.04 (1.78, 9.18)* | 1.71 (0.70, 4.21) |

| Diuretics | 286 | 73 | 1.90 (1.45, 2.48)* | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 186 | 44 | 1.73 (1.23, 2.42)* | 0.78 (0.53, 1.15) |

| Potassium sparing diuretics | 58 | 15 | 1.86 (1.05, 3.30)* | 1.01 (0.55, 1.85) |

| Loop diuretics | 53 | 16 | 2.18 (1.24, 3.82)* | 0.94 (0.50, 1.78) |

| RAS-inhibitors | 266 | 82 | 2.33 (1.80, 3.02)* | 0.99 (0.73, 1.35) |

| ACE inhibitors | 237 | 66 | 2.07 (1.56, 2.75)* | 0.90 (0.65, 1.25) |

| Ang II antagonists | 34 | 19 | 4.06 (2.30, 7.14)* | 1.81 (0.97, 3.35) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 178 | 83 | 3.58 (2.73, 4.70)* | 1.67 (1.22, 2.28)* |

| Dihydropyridine CCB | 113 | 55 | 3.65 (2.62, 5.08)* | 1.76 (1.22, 2.54)* |

| Non-dihydropyridine CCB | 68 | 29 | 3.12 (2.00, 4.84)* | 1.43 (0.87, 2.34) |

Significant (P < 0.05).

Adjusted for age, sex, mean arterial pressure, cholesterol level, smoking, other antihypertensives and use of at least one other cardiovascular drug.

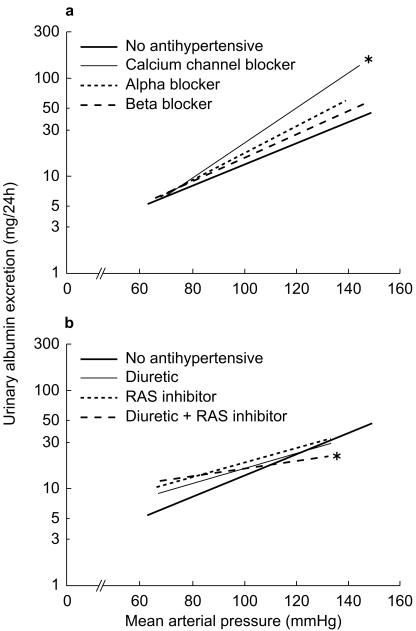

The relation between MAP and (the logarithm of) urinary albumin excretion is shown in Figure 1(a,b), for users of the different antihypertensive drug classes as compared with subjects who do not use antihypertensives. A regression line refers to all users of a drug, thus including subjects using other drugs concurrently. Comparing the lines of different drug groups with the group of subjects not using antihypertensives, the CCBs had a significantly different (steeper) slope (P = 0.0047; Figure 1a). After adjustment of the regression lines for the same factors as in Table 3 again only users of CCBs had a significantly steeper relation (P = 0.0015) between MAP and urinary albumin excretion (data not shown). When analysing the different subclasses of CCBs, only the regression line for dihydropyridine CCBs remained significantly steeper. If the relation between MAP and urinary albumin excretion is analysed for users of combinations of two drug groups, the combination of a RAS inhibitor with a diuretic (136 users) showed a significantly different (less steep) slope (P = 0.037; Figure 1b), after adjustment the slope is still less steep, though not significant (P = 0.16). Other combinations of antihypertensives were not different from the group of nonusers.

Figure 1.

a) and b) Influence of different antihypertensive drug groups on the relation between blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion. The figure is split in two for clarity. Only the combination between a RAS inhibitor and a diuretic is shown, none of the others had a significantly different slope. *Significantly different slope (P < 0.05) as compared with no antihypertensives. Solid bold line no antihypertensive; Solid thin line a) calcium channel blocker, b) diuretic; thick dotted line a) α-adrenoceptor, b) RAS inhibitor; thick dashed line a) β-adrenoceptor blocker, b) diuretic + RAS inhibitor.

Discussion

This study shows a difference between antihypertensive drug classes in their association with microalbuminuria and in their influence on the relation between blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion in a general practice. Interestingly, of the antihypertensive drugs, only dihydropyridine CCBs show a relation with microalbuminuria in a multivariate regression model, while other antihypertensive drug groups show no association in this model. Moreover, only when ACE inhibitors are combined with a diuretic, they show their superiority over other antihypertensives in protecting against microalbuminuria (Figure 1b).

Our findings that the use of dihydropyridine CCBs is associated with an elevated urinary albumin excretion can be explained by their dilating effect on the afferent glomerular arterioles. If systemic blood pressure is higher, this induces glomerular hypertension and could therefore lead to an increased urinary albumin excretion. The observed regression line of CCB-users (Figure 1a) indicates that CCBs are associated to a higher urinary albumin excretion in subjects with high blood pressure. In everyday practice, this would suggest that if hypertension is treated with a CCB, the physician should take care that the blood pressure is lowered far enough. Furthermore, only dihydropyridine CCBs are associated with an increased urinary albumin excretion, while nondihydropyridine CCBs are not (Table 3). These findings are in agreement with a recent meta-analysis, which showed a negative effect of nifedipine on microalbuminuria as compared with other CCBs [12].

Interestingly, our data did not show the expected superiority of ACE inhibitors and Ang II antagonists in protecting against microalbuminuria, unless combined with a diuretic. There can be two reasons for this lack of effect. First, if it was already known that subjects had microalbuminuria there is a higher chance that they would be prescribed an ACE inhibitor or Ang II antagonist. We tried to minimize this channelling by excluding all diabetic subjects, since measurement of urinary albumin excretion today is restricted mainly to this group and is rarely performed in nondiabetics. Second, the lack of superiority could be due to the fact that in general practice the albuminuria lowering effect of ACE inhibitor therapy is not visible anymore in the long term. ACE inhibitors are most effective in lowering hypertension and proteinuria in volume depleted conditions, by following a low sodium diet or by addition of diuretics [20]. Interestingly, we did find a significantly altered relation between blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion for users of the combination of a RAS inhibitor and a diuretic.

Since microalbuminuria is known to be more prevalent in subjects with hypertension, the univariate relation with antihypertensives was to be expected. We also found other cardiovascular drug groups to be used more frequently by microalbuminuric subjects. The association found for anticholesterolaemic agents, even after adjustment for cholesterol level, is remarkable and should be investigated further. The association with drugs used in subjects with manifest cardiovascular diseases, such as angina pectoris (nitrates), arrhythmias (antiarrhythmics and cardiac glycosides), heart failure (glycosides) and thrombotic events was to be expected. Indeed cardiovascular disease is seen more frequently in microalbuminurics [1–3]. However, up till now nobody has shown that reducing or slowing down the progression of urinary albumin excretion in a nondiabetic population prevents renal or cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and further research on this subject needs to be done [21].

There are some shortcomings in this study. First, none of these drugs is indicated for hypertension alone, thus it could be that the relations we found are confounded by indication. However, by adjusting the odds ratios for use of other antihypertensives and cardiovascular drugs we tried to correct for this bias. Furthermore, CCBs are not the first choice in the treatment of hypertension, leaving the possibility for confounding by severity of indication. However, this cannot explain why we found a higher urinary albumin excretion for a given blood pressure during CCB use (Figure 1a). Second, this is only a cross-sectional analysis, and therefore does not allow us to draw conclusions on a cause and effect relation. Prospective follow up of this cohort with continuous monitoring of pharmacy records will in the future show whether antihypertensive drug groups are able to lower urinary albumin excretion or to slow down its progressive rise.

In conclusion, this study suggests a disadvantageous effect of CCBs on microalbuminuria compared with other antihypertensive drug groups, especially when the CCB therapy does not reach sufficient blood pressure lowering. If such data could be confirmed in a prospective follow up study, as is presently being carried out, it can be concluded that dihydropyridine CCBs are not the agents of choice to lower blood pressure, while the combination of RAS inhibition with a diuretic seems to be preferred.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Paul van den Berg and the public pharmacies in the city of Groningen for helping with the collection of pharmacy data. This study is in part financially supported by grant E.013 of the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Nierstichting Nederland).

In addition to the authors, the PREVEND investigators are, from the University Hospital of Groningen, the Netherlands: Department of Internal Medicine (Division of Nephrology): G. J. Navis MD, S.-J. Pinto-Sietsma MD, A. H. Boonstra MD; Department of Internal Medicine: R. O. B. Gans MD, A. J. Smit MD; Department of Cardiology: H. J. G. M. Crijns MD, A. J. van Boven MD; from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands: Department of Clinical Pharmacology: W. H. van Gilst MD, D. de Zeeuw MD, H. L. Hillege MD; Social Pharmacy and Pharmacoepidemiology: M. Postma PhD; Department of Medical Genetics: G. J. te Meerman PhD; Municipal Health Department, Groningen, the Netherlands: J. Broer MD; Julius Center for Patient Oriented Research, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands: A. A. A. Bak, de Grobbee.

References

- 1.Yudkin JS, Forrest RD, Jackson CA. Microalbuminuria as predictor of vascular disease in non-diabetic subjects. Islington Diabetes Survey. Lancet. 1988;ii:530–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Clausen P, Appleyard M, Jensen G. Microalbuminuria and its relation to cardiovascular disease and risk factors. A population based study of 1254 hypertensive individuals. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:727–732. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S, Schroll M, Borch-Johnsen K. Arterial hypertension, microalbuminuria, and risk of ischemic heart disease. Hypertension. 2000;35:898–903. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.4.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parving H-H. Benefits and cost of antihypertensive treatment in incipient and overt diabetic nephropathy. J Hypertens Suppl. 1998;16:S99–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parving H-H. Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension and diabetes mellitus. J Hypertens Suppl. 1996;14:S89–S94. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199609002-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen WMT, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D. Hypertension and renal disease: role of microalbuminuria. J Hypertens Suppl. 1996;14:S173–S177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redon J. Renal protection by antihypertensive drugs: insights from microalbuminuria studies. J Hypertens. 1998;16:2091–2100. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimran A, Ribstein J, du Cailar G. Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:359–363. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199905000-00014. 10.1097/00041552-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogensen CE. Microalbuminuria, blood pressure and diabetic renal disease: origin and development of ideas. Diabetologia. 1999;42:263–285. doi: 10.1007/s001250051151. 10.1007/s001250051151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maki DD, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Kasiske BL. Long-term effects of antihypertensive agents on proteinuria and renal function. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1073–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erley CM, Haefele U, Heyne N, Braun N, Risler T. Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension. Reduction by different antihypertensive drugs. Hypertension. 1993;21:810–815. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gansevoort RT, Sluiter WJ, Hemmelder MH, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE. Antiproteinuric effect of blood-pressure-lowering agents: a meta-analysis of comparative trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:1963–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giatras I, Lau J, Levey AS. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition and Progressive Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:337–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preston RA. Renoprotective effects of antihypertensive drugs. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:19S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcantoni C, Jafar TH, Oldrizzi L, Levey AS, Maschio G. The role of systemic hypertension in the progression of nondiabetic renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;57(Suppl. 75):S44–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedrinelli R, Dell'Omo G, Penno G, et al. Microalbuminuria and pulse pressure in hypertensive and atherosclerotic men. Hypertension. 2000;35:48–54. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto-Sietsma S-J, Janssen WMT, Hillege HL, Navis G, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE. Urinary albumin excretion is associated with renal functional abnormalities in a nondiabetic population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1882–1888. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11101882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klungel OH, de Boer A, Paes AH, Herings RM, Seidell JC, Bakker A. Agreement between self-reported antihypertensive drug use and pharmacy records in a population-based study in The Netherlands. Pharm World Sci. 1999;21:217–220. doi: 10.1023/a:1008741321384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. ATC Index with DDDs 1999. Oslo: WHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buter H, Hemmelder MH, Navis G, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D. The blunting of the antiproteinuric efficacy of ACE inhibition by high sodium intake can be restored by hydrochlorothiazide. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1682–1685. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.7.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diercks GFH, Janssen WMT, van Boven AJ, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of a trial of prevention of cardiovascular and renal disease with fosinopril and pravastatin in nonhypertensive, nonhypercholesterolemic subjects with microalbuminuria (the prevention of renal and vascular endstage disease intervention trial [PREVEND IT]) Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:635–638. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]