Abstract

A large number of human cancers display alterations in the Ink4a/cyclin D/Cdk4 genetic pathway, suggesting that activation of Cdk4 plays an important role in oncogenesis. Here we report that Cdk4-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts are resistant to transformation in response to Ras activation with dominant-negative (DN) p53 expression or in the Ink4a/Arf-null background, judged by foci formation, anchorage-independent growth, and tumorigenesis in athymic mice. Cdk4-null fibroblasts proliferate at normal rates during early passages. Whereas Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− cells are immortal in culture, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cells undergo senescence during continuous culture, as do wild-type cells. Activated Ras also induces premature senescence in Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cells and Cdk4−/− cells with DNp53 expression. Thus, Cdk4 deficiency causes senescence in a unique Arf/p53-independent manner, which accounts for the loss of transformation potential. Cdk4-null cells express high levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 with increased protein stability. Suppression of p21Cip1/Waf1 by small interfering RNA (siRNA), as well as expression of HPV-E7 oncoprotein, restores immortalization and Ras-mediated transformation in Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cells and Cdk4−/− cells with DNp53 expression. Therefore, Cdk4 is essential for immortalization, and suppression of Cdk4 could be a prospective strategy to recruit cells with inactive Arf/p53 pathway to senescence.

Keywords: Cell cycle, cancer, immortalization, cyclin, Cdk, Ras, Ink4a, p21, stability

Perturbed control of the G1 phase of the cell cycle is a critical step for cellular transformation and tumorigenesis (Hartwell and Kastan 1994; Hunter 1997; Hanahan and Weinberg 2000; Sherr 2000). The balance of growth-stimulatory and inhibitory signals regulates G1 progression as well as the transition between quiescence (G0) and proliferation (Pardee 1989; Kiyokawa 2002). Cyclin D-dependent kinases play an important role in integrating extracellular signals into the cell-cycle machinery (Sherr 2000). D-type cyclins bind to and activate Cdk4 and Cdk6 during G1 (Matsushime et al. 1992; Meyerson and Harlow 1994). This is followed by activation of Cdk2 in complex with cyclin E in late G1, which is essential for initiation of the S phase. Cdk2 also binds to cyclin A during S phase, playing a critical role in DNA replication. The activities of Cdk4 and Cdk6 are regulated specifically by the Ink4-type inhibitors (p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b, p18Ink4c, and p19Ink4d), whereas Cdk2 is inhibited by the Kip/Cip-type inhibitors (p21Cip1/Waf1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2; Kiyokawa and Koff 1998; Sherr and Roberts 1999). Cyclin D/Cdk4(Cdk6) phosphorylates retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and the other Rb-related pocket binding proteins p107 and p130 (Ewen et al. 1993; Kato et al. 1993; Leng et al. 2002). Cdk4-dependent phosphorylation of specific sites of Rb presumably facilitates Cdk2-dependent phosphorylation of other sites (Kitagawa et al. 1996; Connell-Crowley et al. 1997; Zarkowska and Mittnacht 1997; Boylan et al. 1999). The hyperphosphorylation of Rb promotes conversion of the E2F transcription factors from repressor to transactivator status, which results in expression of various genes essential for the S phase, including cyclins E and A (Nevins 2001). Furthermore, cyclin D/Cdk4 in proliferating cells binds to p21Cip1/Waf1 and p27Kip1 without being inactivated (Soos et al. 1996; Blain et al. 1997; Sherr and Roberts 1999). These Kip/Cip proteins rather promote assembly of cyclin D/Cdk4 (LaBaer et al. 1997), suggesting that the physical interaction with cyclin D/Cdk4 titrates p21 and p27 populations available for Cdk2 inhibition. Therefore, Cdk4 plays both catalytic and noncatalytic roles in control of G1 progression.

A large number of human cancers show genetic alterations that deregulate cyclin D/Cdk4 (Hirama and Koeffler 1995; Pestell et al. 1999; Sherr 2000). Many glioblastomas, gliomas, and sarcomas display Cdk4 overexpression due to gene amplification (Khatib et al. 1993). Melanoma-prone families have been found to carry germline mutations of Cdk4 at the Arg24 residue that render the kinase refractory to Ink4-dependent inhibition (Wolfel et al. 1995; Zuo et al. 1996). Various types of cancer show overexpression of D-type cyclins. More frequent cancer-associated alterations are deletions, mutations, and methylation of the Ink4a/Arf locus (Kamb et al. 1994; Sherr 1998; Sharpless and DePinho 1999). The Ink4a/Arf locus contains two independent genes encoding p16Ink4a and p14Arf (p19Arf in mice), which share exons 2 and 3 on alternative reading frames (Quelle et al. 1995). Whereas p16Ink4a inhibits Cdk4 and Cdk6, Arf protein interferes with Mdm2-dependent degradation of the tumor suppressor p53, leading to stabilization of p53 (Pomerantz et al. 1998; Stott et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998). Thus, inactivation of the Ink4a/Arf locus results in inappropriate activation of Cdk4 and rapid degradation of p53, both of which could contribute to tumorigenesis in distinct but cooperating manners. Consistent with this notion, mice deficient in both p16Ink4a and p19Arf (Serrano et al. 1996) or mice deficient in p19Arf with intact p16Ink4a (Kamijo et al. 1997) develop spontaneous tumors. Mice lacking p16Ink4a with intact p19Arf are susceptible to tumorigenesis to a lesser extent (Krimpenfort et al. 2001; Sharpless et al. 2001). These data suggest that activation of Cdk4 plays a critical role in tumorigenesis.

To further clarify the role of Cdk4 in cell-cycle control and tumorigenesis, we recently generated mice with targeted disruption of the Cdk4 gene. Cdk4-null mice are viable, and exhibit diabetes mellitus due to degeneration of pancreatic β-cells and growth retardation and infertility associated with severe hypoplasia and dysfunction of the pituitary (Tsutsui et al. 1999; Moons et al. 2002a,b). Embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Cdk4-null mice proliferate at normal rates, while they display a 4–5-h delay in entry into the cell cycle from quiescence (Tsutsui et al. 1999). Therefore, Cdk4 is rate-limiting for cell-cycle entry but is dispensable for cell-cycle progression. However, it was unclear whether Cdk4 plays an essential role in immortalization and transformation. In this study, we demonstrate that Cdk4 is required for Ras-mediated transformation of MEFs, and that Cdk4 disruption leads cells to Arf/p53-independent senescence. These findings provide a significant foundation for anticancer therapies that target the cyclin D/Cdk4 pathway.

Results

Cdk4-null MEFs are resistant to transformation in response to Ras activation and p53 inhibition

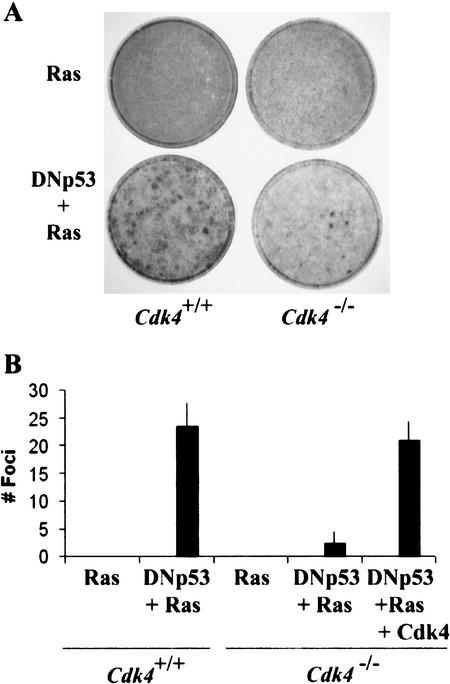

To examine the effect of Cdk4 disruption on transformation potential, we prepared Cdk4+/+ and Cdk4−/− MEFs from embryos obtained from intercross breeding of Cdk4+/− mice (Tsutsui et al. 1999). Cells at early passages (passage 3–4) were infected with a retrovirus for expression of oncogenic H-RasVal12 and a dominant-negative p53 mutant (DNp53), previously described as GSE56 (Ossovskaya et al. 1996). DNp53 encodes the amino acids 275–368 of p53, and suppresses p53 activity, presumably by interfering with oligomerization of the protein. Under standard culture conditions with 10% fetal bovine serum, Cdk4−/− MEFs proliferated at rates indistinguishable from those of Cdk4+/+ MEFs, as demonstrated previously (Tsutsui et al. 1999). Following retroviral transduction of H-RasVal12, with or without DNp53, cells were cultured for 21 d without splitting and then stained to visualize transformed foci (Fig. 1). Strikingly, the numbers of foci developed in Cdk4−/− MEF cultures expressing H-RasVal12 and DNp53 were 95% reduced, relative to those in Cdk4+/+ cultures. Retroviral transduction of H-RasVal12 alone or DNp53 alone did not result in focus formation in either Cdk4+/+ or Cdk4−/− MEFs. Immunoblotting confirmed that the levels of Ras expression were comparable in Cdk4+/+ and Cdk4−/− cells (data not shown). Retroviral transduction of Cdk4 prior to transduction of H-RasVal12 and DNp53 restored foci formation (Fig. 1B), confirming that the absence of Cdk4 is responsible for the inhibition of foci formation.

Figure 1.

Cdk4-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts are resistant to transformation induced by expression of H-Rasval12 and dominant-negative p53. (A) Passage 4 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with the indicated genotypes were infected with a retrovirus encoding H-Rasval12, or with a virus encoding H-Rasval12 and a dominant-negative p53 (DNp53; amino acids 275–368) with the internal ribosomal entry site. To restore Cdk4 in Cdk4−/− MEFs, cells were infected with a Cdk4 retrovirus 48 h prior to H-Rasval12 + DNp53. Cells were then cultured in the medium containing 5% FBS for 21 d. (B) The numbers of foci per 60-mm dish in the assays are expressed as means + S.E.M. from three independent MEF preparations.

We also examined anchorage-independent growth by plating MEFs in soft agar following retroviral transduction (Supplementary Fig. 1). Whereas Cdk4+/+ MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 and DNp53 efficiently developed colonies in soft agar, Cdk4−/− MEFs did not form detectable colonies under the same conditions. MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 alone or DNp53 alone formed no colonies regardless of the Cdk4 genotype, as expected. These data suggest that Cdk4 disruption inhibits cellular transformation induced by Ras activation and p53 inhibition.

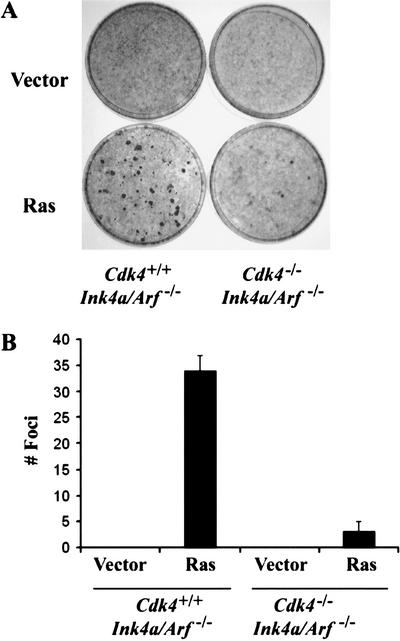

Cdk4−/− Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs are resistant to Ras-induced transformation

To further examine the effect of Cdk4 deficiency on Ras-mediated transformation, we crossed Cdk4-null mice and mice with deletion of the exons 2 and 3 of the Ink4a/Arf locus (Serrano et al. 1996), and prepared Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−and Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−MEFs. Cells at early passage were infected with retrovirus for H-RasVal12 or control virus, and then cultured for 17 d without splitting. Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−MEFs efficiently developed transformed foci upon retroviral transduction of H-Ras (Fig. 2), as previously demonstrated (Serrano et al. 1996). In contrast, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 poorly formed foci, showing 93% reduction in number. No colonies grew when Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−MEFs were inoculated in soft agar following H-RasVal12 transduction, whereas Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−MEFs readily developed colonies (data not shown). These observations suggest that Cdk4 plays a major role in transformation of MEFs induced by Ras activation in the Ink4a/Arf-null background.

Figure 2.

Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs are resistant to HRasval12-induced transformation. (A) Passage 4 MEFs were infected with a retrovirus encoding H-Rasval12, or with a control virus with the pBabe-hygro vector. Cells were then cultured in the medium containing 5% FBS for 17 d. (B) The numbers of foci per 60-mm dish in the assays are expressed as means + S.E.M. from three independent MEF preparations.

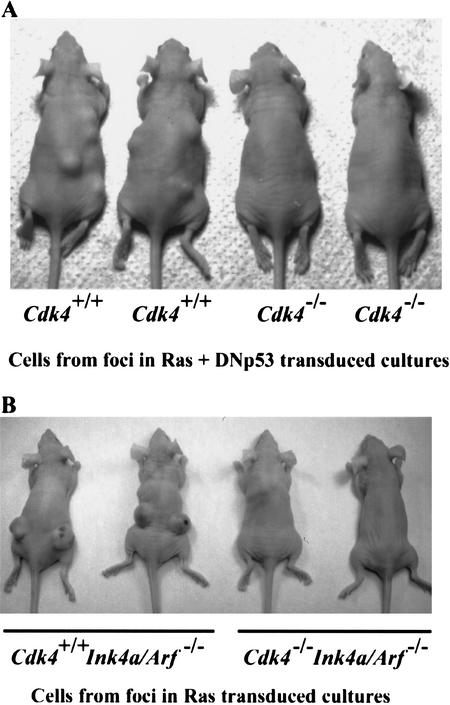

Cdk4-null cells isolated from foci are not tumorigenic in vivo

To determine whether Cdk4-null cells that formed foci were tumorigenic in vivo, we injected athymic mice with Cdk4+/+ and Cdk4−/− MEF clones isolated from foci induced by H-RasVal12 and DNp53, as shown in Figure 1. Cdk4−/− clones exhibited slower proliferation in culture, compared with Cdk4+/+ clones (data not shown). Five independent clones with each genotype were tested (Fig. 3). At 21 d postinjection, all five Cdk4+/+ clones displayed tumor growth, with diameters of 1.7 ± 0.5 cm (mean ± S.E.M.). In contrast, none of five Cdk4−/− clones developed detectable tumors in athymic mice during the 6-wk monitoring period. We also examined the in vivo tumorigenicity of Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−and Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−MEF clones isolated and expanded from foci induced by H-RasVal12, as shown in Figure 2. Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−clones did not develop detectable tumors in athymic mice, whereas mice injected with Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−clones readily displayed large tumors (Fig. 3). These data suggest that Cdk4 disruption abrogates tumorigenicity of MEFs induced by Ras activation with p53 inhibition or Ink4a/Arf disruption.

Figure 3.

Cdk4-null embryonic fibroblasts isolated from foci are not tumorigenic in athymic mice. (A) Foci were isolated from the confluent cultures at 21 d following retrovirus transduction of H-Rasval12 and DNp53 (see Fig. 1). (B) Foci were isolated from the confluent cultures at 17 d following H-Rasval-12 expression (see Fig. 2). Cells were then expanded, and injected into athymic mice (106 cells per site). Mice were examined 21 d after injection.

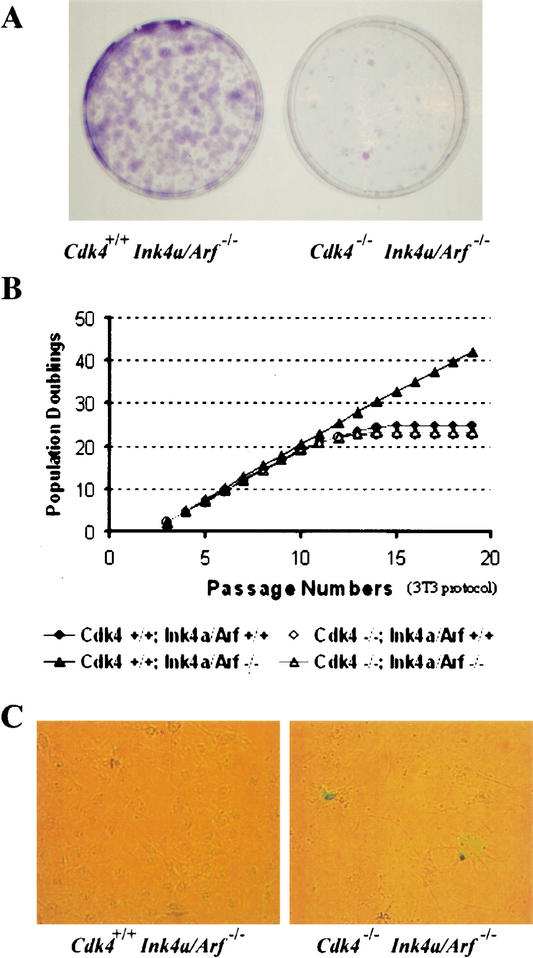

Cdk4 deficiency leads Ink4a/Arf-null MEF to senescence

It is well established that MEFs lacking p53 or Arf are immortal in culture, devoid of “culture shock”-induced senescence, and are readily transformed by activated Ras (Kamijo et al. 1997; Serrano et al. 1997). Immortalization is a process required for the multistep oncogenic transformation. To further investigate the mechanism of the transformation-inhibitory action of Cdk4 disruption, we examined whether Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs showed an immortal phenotype similar to Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs. Cells at a late passage (passage 11) were inoculated at a low density (1000 cells per dish) and cultured for 10 d to score colonies derived from isolated cells (Fig. 4A). Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs formed >200 large colonies, indicating clonogenic proliferation with high plating efficiency. In contrast, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs exhibited very few colonies. These observations suggest that Cdk4 disruption impairs clonogenic proliferation of Ink4a/Arf-null cells. We further assessed the proliferative lifespan of Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− and Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs, monitoring population doublings during continuous culture according to the 3T3 protocol (Fig. 4B). Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs displayed escape from senescence, as expected. In contrast, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs underwent growth arrest after 22–24 population doublings, similarly to wild-type MEFs. Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cells at late passages displayed a flat enlarged morphology and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβ-gal) activity (Fig. 4C), which are characteristic of cellular senescence (Dimri et al. 1995). The senescence phenotype was also observed in cells isolated from foci of Cdk4−/− MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 and DNp53, and in cells isolated from foci of Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 (data not shown). These data suggest that the absence of Cdk4 induces senescence even with Ink4a/Arf disruption or p53 inhibition, which could account for the inhibition of oncogenic transformation.

Figure 4.

Cdk4 disruption renders cells insensitive to immortalization associated with Ink4a/Arf deficiency. (A) MEFs at passage 11 were plated at a low density (1 × 103 cells per 60-mm dish), and cultured for 10 d. Colonies grown from isolated cells were stained with crystal violet. (B) Primary MEFs with indicated genotypes were propagated in culture according to the 3T3 protocol. Accumulated numbers of population doublings are shown. The data represent experiments using three independent MEF preparations for each genotype. (C) Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβ-gal) staining. MEFs at passage 12 were inoculated at 3 × 103 cells per 60-mm dish, and 10 d later, the cells were stained for SAβ-gal, as described in Materials and Methods.

Cdk4-null MEFs express high levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 with increased stability

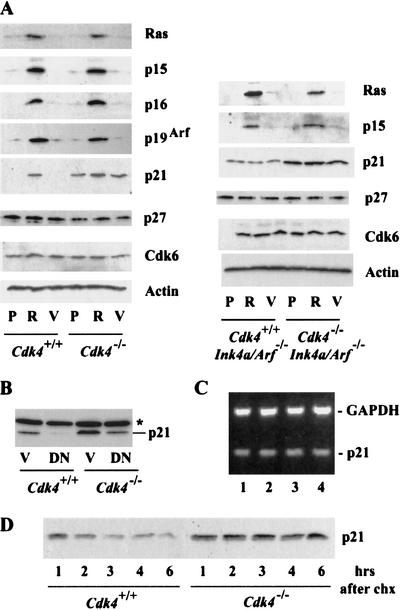

To further investigate the mechanism of the resistance to Ras-mediated transformation in Cdk4-null cells, we examined the expression of proteins that regulate senescence. In primary mouse and human cells, Ras activation or continuous passage in culture induces the expression of p15Ink4b, p16Ink4a, and p21Cip1/Waf1, as well as p19Arf (or p14Arf in human cells; Sherr and DePinho 2000). Cdk4+/+ and Cdk4−/− MEF displayed similar induction of the expression of p15Ink4b, p16Ink4a, and p19Arf following H-RasVal12 transduction (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the basal level of p21Cip1/Waf1 expression was significantly higher in Cdk4−/− cells, relative to Cdk4+/+ cells, and H-RasVal12 transduction increased p21Waf1/Cip1 expression even higher in Cdk4−/− MEFs. Similarly, Cdk4−/− Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs showed higher levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 than Cdk4+/+ Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs. H-RasVal12 did not significantly increase p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in cells with Ink4a/Arf disruption, consistent with the notion that p19Arf plays an essential role in stabilizing p53 and inducing p21Cip1/Waf1 upon Ras activation. H-RasVal12 did not alter the expression of Cdk6 or p27Kip1, regardless of the Cdk4 status. To determine whether the increased basal levels of p21Waf1/Cip1 in Cdk4-null cells are associated with p53 activity, we further examined the effect of DNp53 transduction on cellular expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 (Fig. 5B). DNp53 significantly down-regulated p21Cip1/Waf1 expression in both Cdk4+/+ and Cdk4−/− MEFs, confirming the role of p53 in p21Cip1/Waf1 transcription. In Cdk4−/− MEFs, which showed higher basal levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 expression, DNp53 transduction decreased p21Cip1/Waf1 only to a level comparable to the basal levels in Cdk4+/+ cells, suggesting that Cdk4 deficiency increases p21Cip1/Waf1 in a p53-independent manner. In contrast to the increased protein levels, the cellular amounts of p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA were unchanged in Cdk4−/− and Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs (Fig. 5C). We further determined that p21Cip1/Waf1 in Cdk4−/− MEFs is significantly more stable than that in Cdk4+/+ MEFs, examining the degradation of p21Cip1/Waf1 in cells treated with a protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (Fig. 5D). Under these conditions, the degradation of p27Kip1 was similar in Cdk4−/− and Cdk4+/+ MEFs (data not shown). These data suggest that Cdk4 deficiency results in a specific increase in p21Cip1/Waf1, which could play a role in the senescence response.

Figure 5.

Cdk4-null MEFs express high levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 with increased stability regardless of the Arf/p53 status. (A) Cells with indicated genotypes were infected with retrovirus constructed from pBabe-H-Rasval12 or pBabe-hygro control vector. Infected cells were selected for 72 h in the presence of 50 μg/mL hygromycin, and were then analyzed by immunoblotting for the proteins indicated. P, uninfected proliferating cells (no selection); R, cells infected with H-Rasval12 retrovirus; V, cells infected with vector control virus. (B) Cells were infected with retrovirus constructed from LXSN-dominant-negative (DN) p53 or LXSN control vector (V). Infected cells were selected for 72 h in the presence of 2 μg/mL puromycin, and then analyzed by immunoblotting for the expression of p21Cip1/Waf1. *, a band with nonspecific immunoreactivity. (C) Expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA is unaltered. Exponentially proliferating cells at passage 4 were analyzed by RT–PCR for the expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA and GAPDH mRNA. The genotypes of cells: 1, Cdk4+/+ (wild-type); 2, Cdk4−/−; 3, Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−; 4, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−. (D) p21Cip1/Waf1 is stabilized in Cdk4−/− cells. Exponentially proliferating cells were treated with 40 μg/mL cycloheximide (chx) for the times indicated, and cellular levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 were determined by immunoblotting. These data represent experiments using three independent cell preparations at passage 3 or 4 for each genotype.

Suppression of p21Cip1/Waf1 by siRNA restores immortalization and Ras-mediated transformation in Cdk4-null MEFs

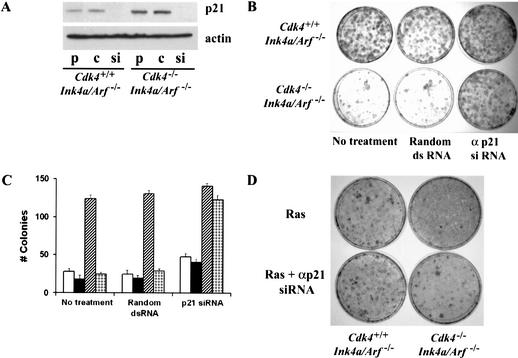

To determine whether elevated p21Cip1/Waf1 expression in Cdk4-null MEFs is required for the inhibition of immortalization and transformation, we used small interfering RNA (siRNA) to suppress cellular expression of p21Cip1/Waf1. A 21-mer double-stranded RNA designed specifically from residues 136–156 of the coding region of mouse p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA was able to suppress cellular p21Cip1/Waf1 expression by more than 90%, suggesting that a majority of cells were successfully transfected (Fig. 6A). The siRNA-based suppression of p21Cip1/Waf1 significantly restored clonogenic proliferation in low-density cultures of Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs (Fig. 6B,C), suggesting that the elevated p21Cip1/Waf1 expression plays a critical role in the limited proliferative lifespan. Moreover, siRNA-mediated suppression of p21Cip1/Waf1 was able to restore foci formation significantly in Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cultures in response to H-RasVal12 transduction (Fig. 6D). The numbers of Ras-induced foci in siRNA-treated Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− cultures were about 75% of those in control Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− cultures (24 ± 3 vs. 32 ± 4, mean ± S.E.M., n = 3). The anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA treatment increased foci formation modestly (∼25%) in Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− cultures. Transfection of the anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA also restored foci formation significantly in Cdk4−/− MEFs with transduction of H-RasVal12 and DNp53 (data not shown). These data suggest that increased expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 by protein stabilization, which is independent of the Arf/p53 function, plays an essential role in the resistance of Cdk4-null cells to immortalization and Ras-mediated transformation.

Figure 6.

Suppression of p21Cip1/Waf1 expression by siRNA restores immortalization and transformation in Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs. (A) Cells at passage 10 were transfected with siRNA that specifically targets p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA or with random double-stranded (ds) RNA. Cellular expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 was analyzed by immunoblotting at 72 h after transfection. p, nontransfected proliferating cells; c, cells transfected with control random dsRNA; si, anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA. (B) Cells at passage 10 were transfected with the anti-p21 siRNA or control dsRNA, and 24 h later plated at a density of 1 × 103 cells/plate. (C) Colonies (>2 mm) were counted at 10 d postplating, and the numbers are expressed as means + S.E.M. from three independent cell preparations. Open columns, Cdk4+/+; closed columns, Cdk4−/−; hatched columns, Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/−; dotted columns, Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/−. (D) Cells at passage 4 were transfected with the anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA or control dsRNA, and 24 h later infected with H-Rasval-12 retrovirus. Foci formation was scored at 15 d posttransfection.

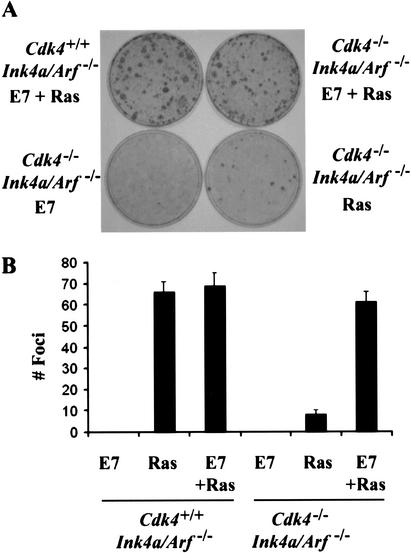

The HPV E7 protein fully restores transformation in Cdk4-null MEF

The E7 oncoprotein of the human papillomavirus-16 (HPV) inactivates Rb by sequestration and destabilization (Dyson et al. 1989; Boyer et al. 1996). E7 has also been shown to bind to the C terminus of p21Cip1/Waf1 and inactivate its Cdk-inhibitory and replication-inhibitory actions (Funk et al. 1997). Thus, we attempted to determine whether the expression of E7 could restore the transformation potential in Cdk4-null cells (Fig. 7). E7 was expressed in Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− and Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs by retroviral transduction, followed by transduction of H-RasVal12 or control vector. Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 and E7 developed a number of transformed foci comparable to Cdk4+/+Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 with or without E7. Expression of E7 alone did not result in foci formation. The E7 retrovirus also restored foci formation in Cdk4−/− MEFs upon expression of H-RasVal12 and DNp53 almost completely (data not shown). These data indicate that the HPV E7 oncoprotein fully restores the transformation potential of Cdk4-disrupted cells.

Figure 7.

Human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein restores Ras-mediated transformation of Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs. (A) Passage 4 MEFs with indicated genotypes were infected with E7 retrovirus or control virus, followed by infection with H-Rasval-12 retrovirus or control virus at a 24-h interval. Cells were then cultured in the medium containing 5% FBS for 17 d. (B) The numbers of foci per 60-mm dish in the assays are expressed as means + S.E.M. from three independent MEF preparations.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that Cdk4-null MEFs are resistant to Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Cdk4-null MEFs proliferate normally under optimal growth-promoting conditions, whereas cell-cycle entry from serum deprivation-induced quiescence is modestly delayed (Tsutsui et al. 1999). Ras activation with p53 inhibition or Ink4a/Arf disruption in Cdk4-null cells results in dramatically reduced foci formation and no detectable proliferation in soft agar. These data suggest that Cdk4 disruption suppresses the two hallmarks of transformed phenotype, lack of contact inhibition and anchorage-independent proliferation (Hartwell and Kastan 1994; Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). Moreover, rare Cdk4-null cells that have apparently lost contact inhibition are not tumorigenic in athymic mice. These observations provide potentially significant insight into prospective therapeutic strategies, implying that genetic or pharmacological suppression of Cdk4 could be an effective approach to render cells insensitive to oncogenic stimuli, without detrimental effects on normal cell-cycle progression. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that Cdk4-null mice display 97% reduction in susceptibility to carcinogen (DMBA and TPA)-induced skin tumorigenesis (Rodriguez-Puebla et al. 2002). Keratinocytes of Cdk4-null mice exhibit normal proliferation and differentiation, indicating that Cdk4 disruption abrogates transformation potential in vivo without affecting tissue development. Other recent studies demonstrated that cyclin D1-null mice are resistant to skin tumorigenesis induced by the same carcinogens (Robles et al. 1998) and also insensitive to mammary tumorigenesis mediated by MMTV-Ras or Neu (Yu et al. 2001). However, it has been shown that 3T3-immortalized cyclin D1-null MEF clones are sensitive to Ras-induced transformation (Yu et al. 2001). This is in contrast to the transformation resistance of Cdk4-null primary MEFs demonstrated in the present study. It is unknown whether cyclin D1 deficiency leads cells to premature senescence. It remains to be determined whether Ras-induced transformation of cyclin D1-null MEFs is related to uncharacterized genetic alterations during 3T3 immortalization, for example, Rb mutations, or activation of Cdk4 by other cyclins, such as cyclins D2 and D3.

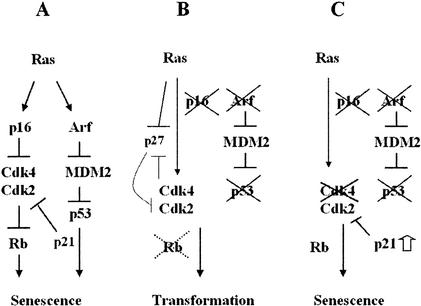

The present study provides evidence that Cdk4 disruption inhibits transformation by recruiting cells to senescence under conditions of p53 inhibition or Ink4a/Arf disruption, which normally immortalize cells (Serrano et al. 1996; Kamijo et al. 1997). This finding is important in the light of an emerging concept that cellular senescence or organismal aging is a major tumor suppressive mechanism in mammals (Sharpless and DePinho 2002). Expression of activated Ras in primary fibroblasts induces premature senescence phenotypes, such as G1 arrest, the large flat morphology, and SAβ-gal activity, indistinguishable from replicative or “culture shock”-induced senescence (Serrano et al. 1997; Sherr and DePinho 2000). To induce senescence, p16Ink4a and p19Arf function in parallel yet interacting pathways (Fig. 8; Carnero et al. 2000; Sherr and DePinho 2000). Whereas p16Ink4a inhibits Cdk4 and Cdk6, p19Arf increases p21Cip1/Waf1 transcription by p53 stabilization, consequently inhibiting cyclin E(A)/Cdk2. The inhibition of these G1-Cdks results in G1 arrest with decreased phosphorylation of Rb and other G1/S-specific substrates. Thus, the senescence response upon oncogene activation forms a safeguard mechanism against transformation. MEFs lacking p19Arf or p53 show the alternative response to Ras activation, undergoing transformation instead of senescence (Kamijo et al. 1997). These observations indicate essential roles for the Arf/p53 pathway in senescence-dependent tumor suppression. Coexpression of an “immortalizing oncogene,” such as adenovirus E1A or c-myc, with activated Ras can also transform MEFs (de Stanchina et al. 1998; Zindy et al. 1998). It is speculated that these immortalizing oncogenes trigger apoptotic response via the Arf/p53 checkpoint pathway, and select for emergence of cell variants that have lost Arf or p53 function (Sherr and DePinho 2000). Consistently, Cdk4-null MEFs are resistant to transformation in response to retroviral transduction of c-Myc and H-RasVal12 (X. Zou and H. Kiyokawa, unpubl.). Whereas Ras triggers cell cycle-inhibitory changes in the expression of p16Ink4a, p19Arf, p53, and p21Cip1/Waf1, Ras also increases transcription of cyclin D1, which results in activation of Cdk4 (Pestell et al. 1999). Furthermore, Ras up-regulates Cdk2 activity by destabilizing p27Kip1 (Pruitt and Der 2001). These cell cycle-promoting actions are important for Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Therefore, the Arf/p53 pathway normally determines whether Ras activation results in premature senescence or transformation. Senescence of Cdk4-null MEFs without Ink4a/Arf or p53 function suggests that Cdk4 plays a key role in the oncogenic mechanism that converts the cell fate from senescence to transformation, in response to genetic or epigenetic alterations in the Arf/p53 checkpoint pathway. Cdk4 disruption is a unique approach to activate the senescence-dependent tumor suppressive mechanism in cells even with Ink4a/Arf or p53 inactivated.

Figure 8.

Effects of Cdk4 disruption on the pathways controlling senescence and transformation. (A) Senescence response of wild-type cells to Ras activation. (B) Ras-induced transformation with inactivated Ink4a/Arf/p53 pathway. (C) Senescence rendered by Cdk4 disruption.

Immortalization of Cdk4-null cells restored by anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA indicates that p21Cip1/Waf1 plays a critical role in the Arf/p53-independent senescence facilitated by Cdk4 deficiency. However, p21Cip1/Waf1-null MEFs with intact Cdk4 senesce normally (Pantoja and Serrano 1999), and MEFs from p21Cip1/Waf1, Cdk4-double null mice poorly undergo transformation upon expression of H-RasVal12 and DNp53 (X. Zou and H. Kiyokawa, unpubl.). These apparently differential effects of p21Cip1/Waf1 inactivation may result from the difference between germline disruption and acute somatic loss of p21Cip1/Waf1. p21Cip1/Waf1-null mice may undergo developmental adaptation to the absence of p21Cip1/Waf1, for which other Kip/Cip inhibitors and possibly p130 (Coats et al. 1999), could account. In contrast, the siRNA-based p21Cip1/Waf1 suppression in MEFs could have more dramatic effects, whereas with intact Arf, the immortalizing effect of anti- p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA was minimum (Fig. 6C). It is also possible that a cell cycle-inhibitory action of p19Arf independent of p53 or p21Cip1/Waf1 (Ferbeyre et al. 2002) may play a role in inducing senescence in p21Cip1/Waf1-null MEFs. Cdk4-null MEFs display increased expression of p21Cip1/Waf1 with enhanced protein stability. Cdk4-null MEFs expressing H-RasVal12 display increased amounts of p21Cip1/Waf1/Cdk2 complexes, relative to wild-type controls (X. Zou and H. Kiyokawa, unpubl.). These observations also suggest that there is a previously undefined regulatory pathway from Cdk4 to the machinery of p21Cip1/Waf1 degradation. The mechanism of p21Cip1/Waf1 stabilization awaits further investigations.

p16Ink4a is a major Cdk4 inhibitor, and plays a role in senescence-dependent tumor suppression. Forced expression of p16Ink4a inhibits Ras-mediated transformation (Serrano et al. 1995). However, p16Ink4a is dispensable for senescence of primary mouse cells, because p16Ink4a-null MEFs with intact p19Arf senesce as well as wild-type MEFs (Krimpenfort et al. 2001; Sharpless et al. 2001). Furthermore, the ability of Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs to undergo senescence suggests that p16Ink4a is not required for senescence. However, an antisense RNA construct directed toward p16Ink4a can induce extended lifespan in primary wild-type MEFs (Carnero et al. 2000). The acute loss of p16Ink4a in this experimental system may significantly activate Cdk4 to a level sufficient for prolonged proliferation in the clonogenic assay used for the study. p15Ink4b also participates in Ras-induced senescence, and p15Ink4b-null MEFs exhibit modestly increased sensitivity to Ras-dependent transformation (Malumbres et al. 2000). Our preliminary data demonstrate that siRNA-based suppression of p15Ink4b minimally affects Ras-mediated foci formation of Cdk4−/−Ink4a/Arf−/− MEFs (X. Zou and H. Kiyokawa, unpubl.). Therefore, Cdk4 deficiency facilitates the senescence-mediated tumor-suppressive mechanism specifically in a p21Cip1/Waf1-dependent manner, whereas the Ink4 inhibitors are dispensable.

The Rb-family pocket binding proteins, that is, Rb, p107, and p130, are involved in the regulation of senescence and immortalization, especially as substrates of Cdk4. Inactivation of these pocket binding proteins by the papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein, together with telomerase activation, has been shown to immortalize primary human epithelial cells (Kiyono et al. 1998). Disruption of Rb, p107, and p130 in MEFs results in increased proliferation with shortened G1 phase and immortalization (Dannenberg et al. 2000; Sage et al. 2000). Senescence induced by Ras, Arf, or p53 depends on the repressor activity of E2F (Rowland et al. 2002), suggesting the role of the Rb/E2F pathway also as downstream of Arf/p53 in senescence (Fig. 8A). MEFs with targeted Cdk4R24C mutation, which express a constitutively active Cdk4 insensitive to Ink4 inhibitors, exhibit escape from senescence (Rane et al. 2002). Mice with the Cdk4R24C mutation spontaneously develop various tumors such as endocrine and skin tumors (Sotillo et al. 2001; Rane et al. 2002), supporting the notion that the Cdk4 activity plays a key role in immortalization and transformation. In Cdk4-null MEFs, phosphorylation of Rb, especially Ser780, is markedly diminished (Tsutsui et al. 1999). The expression of Cdk6 is unchanged in Cdk4-null MEFs, and thus the role of Cdk6 in cell-cycle progression and immortalization of MEFs remains unclear. The complete restoration of Ras-mediated transformation by E7 suggests that the activities of the Rb-family pocket binding proteins are important for the Arf/p53-independent senescence with Cdk4 disruption.

Efforts are ongoing to identify specific chemical inhibitors of cyclin D/Cdk4 and to apply them to clinical trials (Fry et al. 2001; Honma et al. 2001; Soni et al. 2001). Genetic inactivation of the Ink4a/Arf or p53 locus correlates with poor prognosis in cancer patients, often associated with chemoresistance (Weller 1998; Johnstone et al. 2002). A recent study showed that the senescence response of cancer cells, dependent on these two genetic loci, contributes significantly to the outcome of chemotherapy in vivo (Schmitt et al. 2002). Continuous investigations should clarify how cyclin D/Cdk4 interacts with Ras and Arf/p53 in the process that determines whether cells undergo senescence or immortalization, which should contribute to establishing a solid foundation for therapeutic intervention of the transformation pathways.

Materials and methods

Cells

A targeted null mutation of the Cdk4 gene, Cdk4tm1Kiyo, was created in mouse embryonic stem cells, and mice with germline transmission of this mutation were bred in the recombinant C57BL/6 × 129/svj strain background, as described (Tsutsui et al. 1999). MEFs were prepared from day-12.5 mouse embryos and cultured in the Dulbecco's modified minimum essential medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technology), as described (Tsutsui et al. 1999). MEFs dispersed from each embryo using 0.25% trypsin solution containing 0.53 mM EDTA were cultured in a 100-mm culture dish (passage 1). Cells were then maintained using a 3T3 protocol (3 × 105 cells per 60-mm culture dish passaged every 3 d). The population doubling level during each passage was calculated according to the formula log(final cell number/3 × 105)/log2.

Retroviral transfection

The Phoenix ecotropic virus packaging cells were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) with permission of Gary P. Nolan (Stanford University). The pBabe-hygro vector for expression of H-RasVal12 was described previously (Serrano et al. 1996). The LXSN vector for coexpression of DNp53 (GSE56; Ossovskaya et al. 1996) and H-RasVal12 was constructed using the internal ribosomal entry site. Phoenix cells were transfected with vectors, using the SuperFect transfection reagent (QIAGEN), and culture supernatants containing infectious retrovirus were harvested 48 h posttransfection, as described (Pear et al. 1993). The HPV-E7 retrovirus packaging cell line, PA317 LXSN 16E7, was obtained from ATCC. Virus-containing supernatants were pooled and filtered through a 0.45-mm membrane. Infections of exponentially growing MEFs were performed with 1.5 mL of various dilutions of virus-containing supernatant supplemented with 10 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma) for each 60-mm culture dish. The dilutions of the H-RasVal12 and DNp53+H-RasVal12 used were determined according to the numbers of transformed foci developed in Cdk4+/+ Ink4a/Arf−/− and wild-type MEFs, respectively, in pilot experiments. The E7 retrovirus was used at maximum titers without dilution. After 3 h, cells were rinsed and 5 mL fresh medium was added.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

For suppression of cellular p21Cip1/Waf1 expression, siRNA that specifically targets p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA was designed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Dharmacon Research). The sense sequence was 5′-AACGGUGGAACUUUGACUUCG-3′, corresponding to residues 136–156 of the coding region of mouse p21Cip1/Waf1 mRNA. MEFs were transfected with the anti-p21Cip1/Waf1 siRNA or random 21-mer dsRNA (Dharmacon), using the Oligofectamine reagent (Life Technologies/Invitrogen) according to the instructions of Dharmacon Research.

Immunoblotting and RT–PCR

For immunoblotting, cells were lysed by sonication in a Tween-20-based lysis buffer, and 50 μg of proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western transfer, as described (Tsutsui et al. 1999). Antibodies were obtained from Neomarkers for Ras, Cdk6, and p16Ink4a; from Santa Cruz Biotechnology for p15Ink4b and p21Cip1/Waf1; from Novus Biologicals for p19Arf; from Sigma for actin. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated anti-Ig antibodies and the Supersignal chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce). Signals on X-ray films were quantified with a GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad). For RT–PCR, RNA samples were prepared using TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies/Invitrogen). RT reactions were performed using Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies/Invitrogen). The sequences of primers are 5′-TGTCCAATCCTGGT GATGTCC-3′ and 5′-TCAGACACCAGAGTGCAAGAC-3′ for p21Cip1/Waf1; 5′-CCATCACTGCCACCCAGAAG-3′ and 5′-TGGGTGCAGCGAACTTTATTG-3′ for GAPDH. PCR reactions were performed at 92°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec with 30 cycles, using a DNA Engine thermal cycler (MJ Research). Semiquantitative conditions for the transcripts were worked out using increasing amounts of RNA.

Focus and colony assays

For transformed focus formation, MEFs were cultured in complete medium with 5% FBS without splitting, for 14–21 d after retrovirus infection. Medium was changed every 3 d. Confluent monolayer cultures with foci were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and stained with 4 mg/mL crystal violet in 10% methanol. Unstained foci of morphologically transformed cells were picked under a phase microscope (Nikon), subcloned by limited trypsinization, and expanded for the tumorigenicity assay. For colony formation in soft agar, MEFs at 48 h postviral infection were trypsinized, counted, and inoculated at 106 cells per 60-mm dish in 0.3% Noble agar in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Colonies were scored 21–28 d later. When cells isolated from foci were tested for anchorage-independent growth, 2 × 104 cells were inoculated per dish in the Noble agar medium.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβ-gal) assay

SAβ-gal activity at pH 6.0 was assayed as described (Dimri et al. 1995; Chang et al. 1999). Cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, and then stained in X-gal solution [1 mg/mL X-gal, 0.12 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.12 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 1 mM MgCl2 in PBS at pH 6.0] overnight at 37°C.

Tumorigenicity assay

For in vivo tumor formation, 106 cells isolated and expanded from foci were injected into flanks of 7-wk-old athymic mice (National Cancer Institute). Two mice were used for each clone. Tumor formation was scored every week, and diameters of palpable tumors were recorded.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Wold for providing Ink4a/Arf−/− mice generated in her facility, and Nissim Hay, Pradip Raychaudhuri, Charles Sherr, Igor Roninson, Yinyuan Mo, Xiaoding Peng, Mari Swift, James Artwohl, Rob Streit, and other members of the Kiyokawa laboratory for helpful discussions and advice. This study is supported in part by the American Cancer Society (grant #RPG-00-043-01-CCG).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL kiyokawa@uic.edu; FAX (312) 413-2028.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1033002.

References

- Blain SW, Montalvo E, Massague J. Differential interaction of the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p27Kip1 with cyclin A-Cdk2 and cyclin D2-Cdk4. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25863–25872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan JF, Sharp DM, Leffet L, Bowers A, Pan W. Analysis of site-specific phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein during cell cycle progression. Exp Cell Res. 1999;248:110–114. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnero A, Hudson JD, Price CM, Beach DH. p16INK4A and p19ARF act in overlapping pathways in cellular immortalization. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:148–155. doi: 10.1038/35004020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BD, Xuan Y, Broude EV, Zhu H, Schott B, Fang J, Roninson IB. Role of p53 and p21waf1/cip1 in senescence-like terminal proliferation arrest induced in human tumor cells by chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene. 1999;18:4808–4818. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coats S, Whyte P, Fero ML, Lacy S, Chung G, Randel E, Firpo E, Roberts JM. A new pathway for mitogen-dependent cdk2 regulation uncovered in p27(Kip1)-deficient cells. Curr Biol. 1999;9:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell-Crowley L, Harper JW, Goodrich DW. Cyclin D1/Cdk4 regulates retinoblastoma protein-mediated cell cycle arrest by site-specific phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:287–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg JH, van Rossum A, Schuijff L, te Riele H. Ablation of the retinoblastoma gene family deregulates G(1) control causing immortalization and increased cell turnover under growth-restricting conditions. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:3051–3064. doi: 10.1101/gad.847700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Stanchina E, McCurrach ME, Zindy F, Shieh SY, Ferbeyre G, Samuelson AV, Prives C, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Lowe SW. E1A signaling to p53 involves the p19(ARF) tumor suppressor. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2434–2442. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson N, Howley PM, Munger K, Harlow E. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;243:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewen ME, Sluss HK, Sherr CJ, Matsushime H, Kato J, Livingston DM. Functional interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with mammalian D-type cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:487–497. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90136-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbeyre G, de Stanchina E, Lin AW, Querido E, McCurrach ME, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras and p53 cooperate to induce cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3497–3508. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3497-3508.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DW, Bedford DC, Harvey PH, Fritsch A, Keller PR, Wu Z, Dobrusin E, Leopold WR, Fattaey A, Garrett MD. Cell cycle and biochemical effects of PD 0183812. A potent inhibitor of the cyclin D-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16617–16623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JO, Waga S, Harry JB, Espling E, Stillman B, Galloway DA. Inhibition of CDK activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:2090–2100. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirama T, Koeffler HP. Role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in the development of cancer. Blood. 1995;86:841–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma T, Yoshizumi T, Hashimoto N, Hayashi K, Kawanishi N, Fukasawa K, Takaki T, Ikeura C, Ikuta M, Suzuki-Takahashi I, et al. A novel approach for the development of selective Cdk4 inhibitors: Library design based on locations of Cdk4 specific amino acid residues. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4628–4640. doi: 10.1021/jm010326y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Oncoprotein networks. Cell. 1997;88:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: A link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell. 2002;108:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Harshman K, Tavtigian SV, Stockert E, Day RS, III, Johnson BE, Skolnick MH. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science. 1994;264:436–440. doi: 10.1126/science.8153634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Quelle DE, Downing JR, Ashmun RA, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell. 1997;91:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, Ewen ME, Sherr CJ. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib ZA, Matsushime H, Valentine M, Shapiro DN, Sherr CJ, Look AT. Coamplification of the CDK4 gene with MDM2 and GLI in human sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5535–5541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Higashi H, Jung HK, Suzuki-Takahashi I, Ikeda M, Tamai K, Kato J, Segawa K, Yoshida E, Nishimura S, et al. The consensus motif for phosphorylation by cyclin D1-Cdk4 is different from that for phosphorylation by cyclin A/E-Cdk2. EMBO J. 1996;15:7060–7069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa H. Cell cycle control and cell fate determination: In vivo roles of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases and inhibitors. In: Pandalai SG, editor. Recent research developments in molecular & cellular biology. Vol. 2. Trivandrum, India: Research Signpost; 2002. (In press). [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa H, Koff A. Roles of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: Lessons from knockout mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;227:105–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71941-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono T, Foster SA, Koop JI, McDougall JK, Galloway DA, Klingelhutz AJ. Both Rb/p16INK4a inactivation and telomerase activity are required to immortalize human epithelial cells. Nature. 1998;396:84–88. doi: 10.1038/23962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimpenfort P, Quon KC, Mooi WJ, Loonstra A, Berns A. Loss of p16Ink4a confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35092584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, Slingerland JM, Sandhu C, Chou HS, Fattaey A, Harlow E. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng X, Noble M, Adams PD, Qin J, Harper JW. Reversal of growth suppression by p107 via direct phosphorylation by cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2242–2254. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2242-2254.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Perez DC, I, Hernandez MI, Jimenez M, Corral T, Pellicer A. Cellular response to oncogenic ras involves induction of the Cdk4 and Cdk6 inhibitor p15(INK4b) Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2915–2925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2915-2925.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushime H, Ewen ME, Strom DK, Kato JY, Hanks SK, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Identification and properties of an atypical catalytic subunit (p34PSK- J3/cdk4) for mammalian D type G1 cyclins. Cell. 1992;71:323–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90360-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson M, Harlow E. Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2077–2086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons DS, Jirawatnotai S, Parlow AF, Gibori G, Kineman RD, Kiyokawa H. Pituitary hypoplasia and lactotroph dysfunction in mice deficient for cyclin-dependent kinase-4. Endocrinology. 2002a;143:3001–3008. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons DS, Jirawatnotai S, Tsutsui T, Franks R, Parlow AF, Hales DB, Gibori G, Fazleabas AT, Kiyokawa H. Intact follicular maturation and defective luteal function in mice deficient for cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (Cdk4) Endocrinology. 2002b;143:647–654. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevins JR. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:699–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossovskaya VS, Mazo IA, Chernov MV, Chernova OB, Strezoska Z, Kondratov R, Stark GR, Chumakov PM, Gudkov AV. Use of genetic suppressor elements to dissect distinct biological effects of separate p53 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:10309–10314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja C, Serrano M. Murine fibroblasts lacking p21 undergo senescence and are resistant to transformation by oncogenic Ras. Oncogene. 1999;18:4974–4982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee AB. G1 events and regulation of cell proliferation. Science. 1989;246:603–608. doi: 10.1126/science.2683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear WS, Nolan GP, Scott ML, Baltimore D. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:8392–8396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestell RG, Albanese C, Reutens AT, Segall JE, Lee RJ, Arnold A. The cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in hormonal regulation of proliferation and differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:501–534. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.4.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee HW, et al. The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf, interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM27's inhibition of p53. Cell. 1998;92:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K, Der CJ. Ras and Rho regulation of the cell cycle and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2001;171:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1995;83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane SG, Cosenza SC, Mettus RV, Reddy EP. Germ line transmission of the Cdk4(R24C) mutation facilitates tumorigenesis and escape from cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:644–656. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.644-656.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles AI, Rodriguez-Puebla ML, Glick AB, Trempus C, Hansen L, Sicinski P, Tennant RW, Weinberg RA, Yuspa SH, Conti CJ. Reduced skin tumor development in cyclin D1-deficient mice highlights the oncogenic ras pathway in vivo. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2469–2474. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Puebla ML, Miliani de Marval PL, LaCava M, Moons DS, Kiyokawa H, Conti JC. CDK4 deficiency inhibits skin tumor development but does not affect normal keratinocyte proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:405–411. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64196-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland BD, Denissov SG, Douma S, Stunnenberg HG, Bernards R, Peeper DS. E2F transcriptional repressor complexes are critical downstream targets of p19(ARF)/p53-induced proliferative arrest. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage J, Mulligan GJ, Attardi LD, Miller A, Chen S, Williams B, Theodorou E, Jacks T. Targeted disruption of the three Rb-related genes leads to loss of G(1) control and immortalization. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:3037–3050. doi: 10.1101/gad.843200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Lee S, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16(INK4a) contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell. 2002;109:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Gomez-Lahoz E, DePinho RA, Beach D, Bar-Sagi D. Inhibition of ras-induced proliferation and cellular transformation by p16INK4. Science. 1995;267:249–252. doi: 10.1126/science.7809631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. The INK4A/ARF locus and its two gene products. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— p53: Good cop/bad cop. Cell. 2002;110:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Lee KH, Carrasco D, Castrillon DH, Aguirre AJ, Wu EA, Horner JW, DePinho RA. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Tumor surveillance via the ARF-p53 pathway. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2984–2991. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. The Pezcoller lecture: Cancer cell cycles revisited. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3689–3695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, DePinho RA. Cellular senescence: Mitotic clock or culture shock? Cell. 2000;102:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: Positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni R, O'Reilly T, Furet P, Muller L, Stephan C, Zumstein-Mecker S, Fretz H, Fabbro D, Chaudhuri B. Selective in vivo and in vitro effects of a small molecule inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:436–446. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.6.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soos TJ, Kiyokawa H, Yan JS, Rubin MS, Giordano A, DeBlasio A, Bottega S, Wong B, Mendelsohn J, Koff A. Formation of p27-CDK complexes during the human mitotic cell cycle. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo R, Dubus P, Martin J, de La CE, Ortega S, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Wide spectrum of tumors in knock-in mice carrying a Cdk4 protein insensitive to INK4 inhibitors. EMBO J. 2001;20:6637–6647. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott FJ, Bates S, James MC, McConnell BB, Starborg M, Brookes S, Palmero I, Ryan K, Hara E, Vousden KH, et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14(ARF), participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998;17:5001–5014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui T, Hesabi B, Moons DS, Pandolfi PP, Hansel KS, Koff A, Kiyokawa H. Targeted disruption of CDK4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27Kip1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7011–7019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M. Predicting response to cancer chemotherapy: the role of p53. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:435–445. doi: 10.1007/s004410051072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, De Plaen E, Hankeln T, Meyer zBK, Beach D. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Geng Y, Sicinski P. Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature. 2001;411:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/35082500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkowska T, Mittnacht S. Differential phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein by G1/S cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12738–12746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92:725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zindy F, Eischen CM, Randle DH, Kamijo T, Cleveland JL, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Myc signaling via the ARF tumor suppressor regulates p53-dependent apoptosis and immortalization. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2424–2433. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo L, Weger J, Yang Q, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Walker GJ, Hayward N, Dracopoli NC. Germline mutations in the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4 in familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 1996;12:97–99. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]