Abstract

A 3 1/2-month-old pug with oculonasal discharge and seizures was submitted for postmortem examination. Grossly, the lungs had cranioventral consolidation, and microscopically, 2 distinct types of inclusion bodies compatible with Canine distemper virus and Canine adenovirus type 2. Presence of both viruses was confirmed via immunohistochemical staining.

Résumé

Pneumonie combinée maladie de Carré — adénovirus chez un chien. Un Carlin âgé de 3,5 ans présentant un écoulement oculonasal et des crises a été soumis à un examen post-mortem. Macroscopiquement, les poumons montraient un affermissement crânio-ventral et microscopiquement, 2 types distincts de corps d’inclusion compatibles avec le virus de la maladie de Carré et l’adénovirus canin de type 2. La présence des 2 virus a été confirmée par coloration immunohistochimique.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

An 8-week-old, female pug purchased from a local kennel (Monterrey, Mexico), was taken to a veterinarian for routine examination and vaccination. On clinical examination, the puppy appeared healthy and was vaccinated against Canine distemper virus (CDV), Canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2), Canine coronavirus, Canine parainfluenza virus (CRIV), Canine parvovirus, Leptospira canicola, and L. icterohemorragiae (Recombitek; Merial, El Marqués, Querétaro, Mexico). Two weeks later, a booster vaccination was administered. One week after receiving the 2nd vaccination, the dog became lethargic, anorectic, and dyspneic with bilateral serous oculonasal discharge and was taken to its veterinarian and treated with amoxicillin (Animox; Laboratorios Veterinarios Halvet, Mexico City, Mexico), 15 mg/kg BW, PO, q8h for 3 d, and cephalosporin (Cephalexin; Ceporex, GlaxoSmithKline, Mexico City, Mexico), 20 mg/kg BW, PO, q8h for 7 d. Electrolytes (0.85% physiologic saline and Hartmann’s solutions) and vitamin B complex (Aminolite; Boehringer Ingelheim VetMedica, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico) were also administered to the dog. The respiratory signs continued in spite of treatment, and on day 8 after the initial presentation, the puppy developed neurologic signs characterized by rhythmic contraction of the masticatory muscles and progressive myoclonus. On day 15, the puppy exhibited recurrent episodes of seizures. Based on the respiratory and neurological signs, canine distemper was suspected. On day 25, the dog died and was submitted to the Diagnostic Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nuevo León, for postmortem examination.

At necropsy, the puppy was in fair body condition and moderately dehydrated, but with exudate on the nostrils and conjunctiva. Significant gross postmortem findings were confined to the respiratory and lymphatic systems. The lungs failed to collapse when the thorax was opened and showed cranioventral consolidation affecting 50% of the pulmonary parenchyma. The texture of the nonconsolidate lung was elastic and some imprints were noted on the pleural surface. On cut surface, purulent exudate was observed in the major bronchi of the consolidated lung. Severe atrophy of the palatine tonsils was also noted. No other gross lesions were observed and tissue samples from lung, lymph nodes, tonsils, heart, liver, spleen, and brain were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution for histopathological examination.

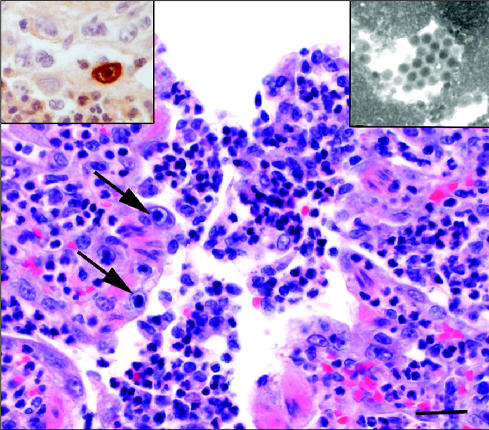

Relevant microscopic lesions were restricted to the lungs and brain. The lungs exhibited severe necrotizing bronchiolitis characterized by swelling and exfoliation of epithelial cells that often resulted in segmental ulceration of the airway mucosa. Mitotic figures and nonciliated flat cells, consistent with proliferating cells at the early stages of repair, were occasionally observed at the margins of ulcerated basement membranes. The bronchial and bronchiolar lumens contained many neutrophils admixed with macrophages and multinucleated syncytial cells (Figure 1). Numerous neutrophils were also present in the mucosa and submucosa of the airways, and the bronchial glands were distended and filled with neutrophils and cell debris. Some alveoli were filled with neutrophils, foamy macrophages and multinucleated cells, and protein-rich edematous fluid. The most remarkable alveolar lesion was a diffuse thickening of the walls resulting from of type II pneumonocyte hyperplasia and interstitial edema.

Figure 1.

Necrotizing bronchiolitis with large numbers of neutrophils in the lumen. Note CAV-2 intranuclear inclusion bodies in the bronchiolar cells (arrowhead). Also note intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies typical of CDV (arrows). Hematoxylin and eosin. Bar = 100 μm. Inset: Canine distemper virus antigen in epithelial cells, Avidin-biotin peroxidase reaction.

Round to oval eosinophilic intranuclear and intracytoplamic inclusion bodies, compatible with CDV, were observed mainly in the bronchial and bronchiolar cells, alveolar macrophages, and multinucleated syncytial cells (Figure 1). Another striking microscopic finding was the distinct presence of large basophilic inclusions in the nuclei of bronchial, bronchiolar, and alveolar cells, consistent with CAV-2 infection (Figure 2). Some of these basophilic inclusions filled the entire nucleus, causing complete margination of the chromatin.

Figure 2.

Necrotizing bronchiolitis with neutrophilic exudation. Note large intranuclear inclusion bodies in the bronchiolar epithelium (arrows). Hematoxylin and eosin. Bar = 100 μm. Left Inset: CAV-2 antigen positive reaction in bronchiolar cell, avidin-biotin peroxidase reaction. Right inset: Paracrystalline arrays of electrondense particles (50 ± 2.0 nm in diameter). Transmission electron microscopy.

Microscopic changes in the central nervous system (CNS) were confined to the cerebellar white matter and consisted of multifocal neuropil vacuolation, astrocytic swelling, and intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions in glial cells, suggestive of CDV infection. There was no evidence of perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes (perivascular cuffing) in the brain, which is commonly seen with CDV infection. Less significant microscopic lesions in other organs included a moderate lymphoid depletion, extramedullary hemopoieisis in the spleen, and intranuclear and intracytoplasmic acidophilic inclusions in the epithelial cells of the renal pelvis. Based on the pulmonary microscopic findings, mainly the distinct features of the intranuclear or intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, a tentative diagnosis of dual canine distemper-adenovirus bronchointerstitial pneumonia was made.

Paraffin-embedded pulmonary tissue was submitted to the Prairie Diagnostics Laboratory in Saskatoon and tested by the avidin-biotin complex-peroxidase technique for CDV and CAV-2, as recommended in the literature (1). Results revealed abundant morbillivirus antigen in the cytoplasm of the bronchial, bronchiolar, alveolar, and glandular epithelia confirming CDV infection (Figure 1). Positive reaction was also observed in alveolar macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. In addition, CAV-2 antigen was detected in the nuclei of the bronchial epithelium, particularly in those cells that contained the large basophilic inclusions (Figure 2). The brain was not tested for CAV-2.

Thin paraffin sections of lung cut at 5 μm were deparaffinized and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Paracrystalline arrays of electron-dense particles measuring 50 ± 2.0 nm in diameter were found in the nuclei of epithelial cells (Figure 2). These electron-dense particles were ultrastructurally consistent with those of CAV-2. Based on histopathologic, histochemical, and electron microscopic findings, the final diagnosis of dual CDV and CAV-2 infection was made in this puppy.

It was not possible to determine either the origin of the dual virus infection or the order in which these infections appeared in the lungs. Perhaps the puppy had low maternal passive immunity or failed to respond to the vaccine due to immune incompetence. Also, it is possible that the puppy was infected with CDV (or CAV-2) in the kennel, prior to vaccination (2). Infections in vaccinated dogs have been reported in countries such as Japan (3).

Bronchointerstitial pneumonias are frequently attributed to viral infections and, to a much lesser extent, to chemical and immune-mediated injury to the lung (4,5). In the absence of inclusion bodies, it is generally difficult to achieve etiological diagnoses in bronchointerstitial pneumonias. In this particular case, however, the presence of 2 distinct types of pulmonary inclusion bodies made the tentative diagnosis relatively simple. Intracytoplasmic inclusions along with the clinical history of respiratory and neurological signs are highly suggestive of canine distemper, while karyomegaly with large intranuclear basophilic inclusion bodies are most consistent with CAV-2 infection (6).

Histochemical staining proved valuable in confirming the dual CDV and CAV-2 infection in this puppy, since culture of these viruses is difficult (1,6). The intralesional distribution of viral antigens in the bronchioles and alveoli was typical of bronchointerstitial pneumonia (4). At the early stages of infection, viral antigens are centered in the areas of bronchiolar necrosis, while in later stages of the disease, the viral antigen is also present in the alveolar macrophages, as was the case with this puppy (5,6). Exfoliated cells exhibiting positive staining for CDV, and to a lesser extent CAV-2, were present in the bronchiolar lumens. The mitotic activity along the denuded bronchiolar basement membranes and the hyperplasia of alveolar type II pneumonocytes clearly indicated that, at the time of death, the lung was undergoing repair (4,5). These findings were chronologically consistent with the 2- to 3-week history of respiratory distress (4).

Canine distemper has a worldwide distribution and is particularly prevalent in geographic areas where vaccination is not routinely performed. It is generally fatal when non-vaccinated or immune incompetent dogs are exposed to a highly pathogenic strains of CDV. It causes a severe necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia, rhinosinusitis and conjunctivitis, nonsuppurative encephalitis with demyelination, gastroenteritis, and severe dehydration (2,7). The perivascular lymphocytes typically seen in the nonsuppurative encephalitis of canine distemper were not observed in this puppy (7). However, the vacuolation of the neuropil and the presence of intranuclear inclusions in glial cells were considered typical of this disease.

The CAV-2 is a highly contagious viral agent that is incriminated in canine respiratory tract disease, particularly in young dogs kept in a crowded environment, such as pet stores, boarding kennels, and veterinary hospitals. This classical syndrome is commonly referred to as kennel cough (8). Infection with CAV-2 is generally transient and seldom fatal, unless it is complicated with a secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia (5,8). In fatal cases, there is a severe bronchointerstitial pneumonia, characterized by necrosis of the bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium, and in some cases, large intranuclear inclusion bodies are seen in bronchiolar and alveolar cells. Like CDV infection, diagnosis of CAV-2 infection is achieved by fluorescent antibody testing (FAT), immunohistochemical staining, or viral isolation.

The suppurative changes observed in the lungs of this puppy were consistent with a secondary bacterial pneumonia. Like many other respiratory viruses, CDV and CAV-2 cause impairment of the pulmonary defense mechanisms and predispose dogs, particularly young puppies, to secondary bacterial pneumonia (5,8). Bordetella bronchiseptica is the most common cause of secondary bacterial pneumonia in dogs (2). Unfortunately, the lungs of this puppy were not cultured and, therefore, the etiologic agent of the suppurative bronchopneumonia remains unknown. It is also possible that distemper encephalitis may have predisposed the puppy to aspiration pneumonia, in spite of the fact that food particles were not seen microscopically in the lung. Although frequently reported in dogs with CDV infection, there was no microscopic evidence in this puppy of diseases caused by other opportunistic infections, such as toxoplasmosis, sarcocystosis, or Tyzzer’s (5,9).

A recent retrospective study of canine viral pneumonias conducted in Mexico revealed 2 important facts regarding CDV and CAV-2 infections in dogs. Firstly, single or combined respiratory infections involving CDV, CAV-2, and CPIV occur more frequently in the canine population than was previously reported (6). Secondly, histopathologic examination alone is not always reliable as a diagnostic tool, since inclusion bodies, the hallmarks for CDV and CAV-2 infection, are not always present in the lung. This is particularly true in the late stages of the disease, as epithelial cells no longer exhibit inclusions during pulmonary repair. Although dual infections with CDV and CAV-2, as seen in this puppy, are uncommonly diagnosed in Mexico (6), similar cases have been reported in other countries (4,10). Detection of bronchointerstitial pneumonia, concurrent with 2 distinct types of inclusion bodies, was very suggestive of a dual viral infection, but immunohistochemical staining was required to confirm the final diagnosis. CVJ

References

- 1.Haines DM, West KH. Immunohistochemistry: Forging the links between immunology and pathology. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;108:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green CA, Apel MJ. Canine Distemper. In: Green CA, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998: 9–20.

- 3.Lan NT, Yamaguchi R, Inomata A, Furuya Y, et al. Comparative analyses of canine distemper viral isolates from clinical cases of canine distemper in vaccinated dogs. Vet Microbiol. 2006;115:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dungworth DL. The respiratory system. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 4th ed. San Diego: Acad Pr, 1993:539–699.

- 5.López A. Respiratory System, Thoracic Cavity, and Pleura. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Diseases. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby-Elsevier, 2007:463–558.

- 6.Damian M, Morales E, Salas G, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of antigens of distemper, adenovirus and parainfluenza viruses in domestic dogs with pneumonia. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summers BA, Cummings JF, De Lahunta A. Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby, 1995.

- 8.Erles K, Dubovi EJ, Brooks HWJ, et al. Longitudinal study of viruses associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4524–4529. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4524-4529.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramirez-Romero R, Gonzalez-Spencer D, Robinson RMDJ, et al. Tyzzer’s disease associated with distemper. A case report. Rev Vet Mex. 1989;20:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi Y, Ochiai K, Itakura C. Dual infection with canine distemper virus and infectious canine hepatitis virus (canine adenovirus type 1) in a dog. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:699–701. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]