Abstract

Obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the UK. It is important because of the associated co-morbidities, which include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and osteoarthritis. The prevalence of obesity has increased because of a combination of excessive calorific intake (for example, from increased intake of energy dense foods) and insufficient energy expenditure (associated with a sedentary lifestyle). Weight loss of 5–10%, which can be achieved in primary care, is associated with significant health benefits. Obesity treatment in primary care includes lifestyle modification and drug treatment. The prevention and treatment of obesity cannot, however, be left solely to health professionals. Action is needed by government, the food industry, and society as a whole.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (124.2 KB).

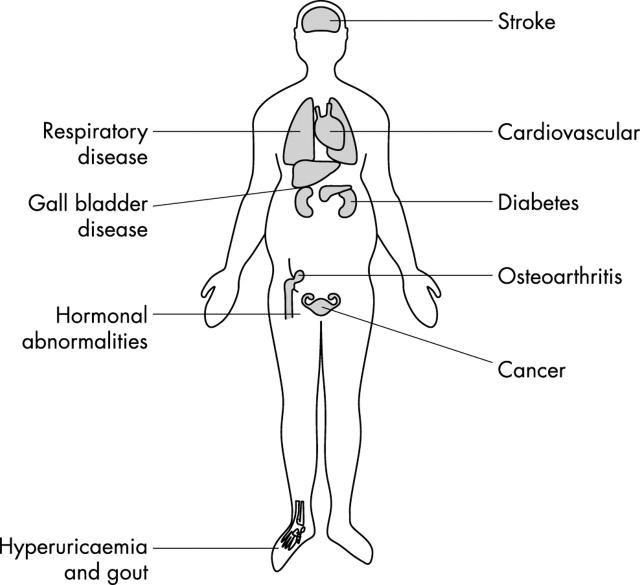

Figure 1 .

Physical effects of obesity.

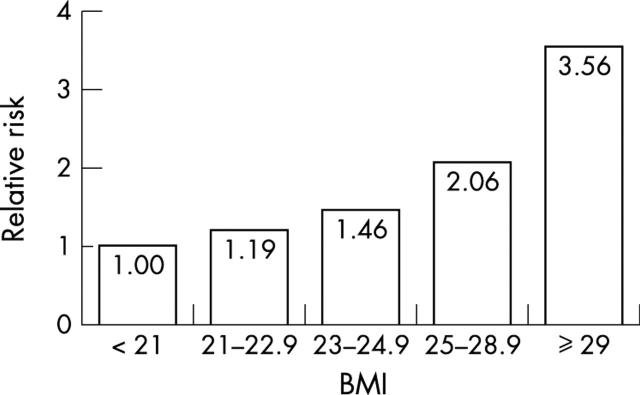

Figure 2 .

Relative risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction and fatal coronary heart disease (combined) versus body mass index (BMI) in women with no previous coronary heart disease. Adapted from Willett et al,6 with permission.

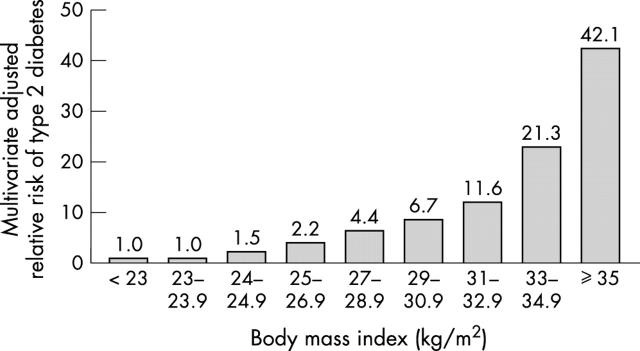

Figure 3 .

Relative risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Adapted from Chan et al,7 with permission.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chan J. M., Rimm E. B., Colditz G. A., Stampfer M. J., Willett W. C. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994 Sep;17(9):961–969. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamothe T., Smith R. PubMed Central: creating an Aladdin's cave of ideas. BMJ. 2001 Jan 6;322(7277):1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7277.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel R. H. Obesity and heart disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997 Nov 4;96(9):3248–3250. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung R. T. Obesity as a disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(2):307–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean M. E., Han T. S., Seidell J. C. Impairment of health and quality of life in people with large waist circumference. Lancet. 1998 Mar 21;351(9106):853–856. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)10004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad A. H., Bowman B. A., Ford E. S., Vinicor F., Marks J. S., Koplan J. P. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2001 Sep 12;286(10):1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W. C., Manson J. E., Stampfer M. J., Colditz G. A., Rosner B., Speizer F. E., Hennekens C. H. Weight, weight change, and coronary heart disease in women. Risk within the 'normal' weight range. JAMA. 1995 Feb 8;273(6):461–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520300035033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]