Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (373.7 KB).

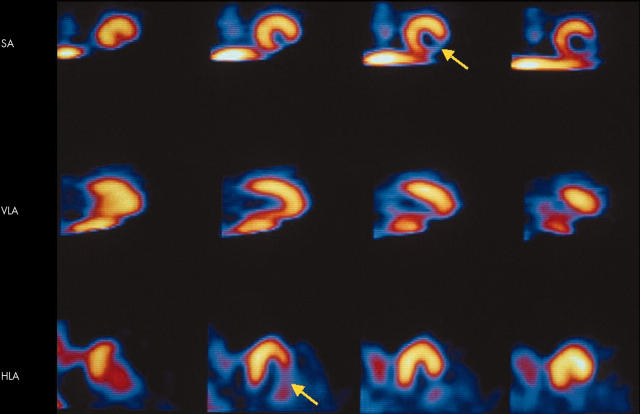

Figure 1.

SPECT resting Tc 99m sestamibi imaging of a 39 year old man who presented to the ED with chest pain, atypical for angina and a near normal initial ECG. The images demonstrate a severe resting perfusion defect in the inferolateral wall. As a result of these findings and of ongoing symptoms, he was taken to the catheterisation laboratory, where an acute left circumflex occlusion was found and treated with primary angioplasty.

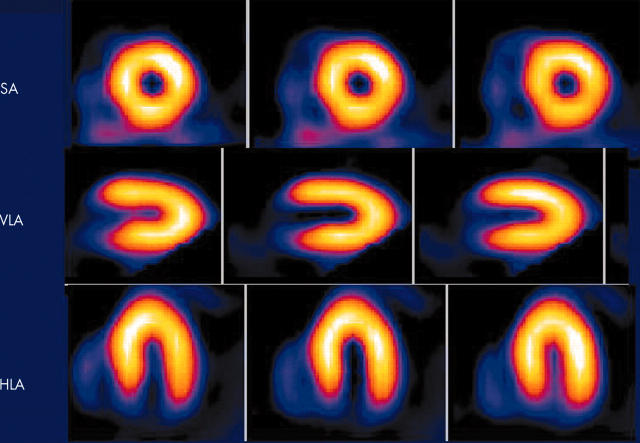

Figure 2.

Short axis, vertical and horizontal long axis SPECT images of a 52 year old man who presented to the ED with chest pain atypical for angina and a initial ECG with non-specific ST segment abnormalities not diagnostic for acute ischaemia. He was injected with tc 99m-sestamibi at rest in the ED, and underwent SPECT imaging in the nuclear cardiology laboratory soon thereafter. The images show a completely normal resting perfusion pattern, and the gated SPECT imaging of resting LV function (not shown) was also normal. This finding is associated with a very low probability of MI and acute ischaemic syndrome, suggesting that such a patient may be discharged directly from the ED.

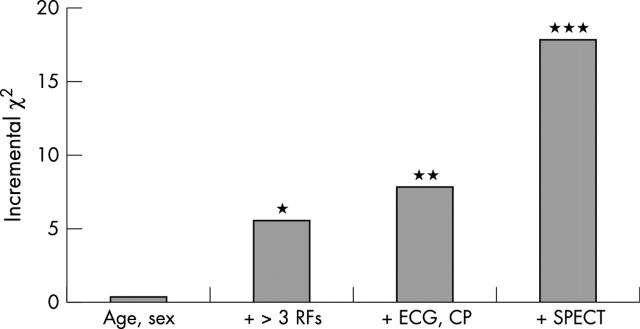

Figure 3.

Analysis of the incremental value of resting perfusion imaging data to predict cardiac events in ED patients with suspected ischaemia. The incremental χ2 value (y axis) measures the strength of the association between individual factors added to the knowledge base in incremental fashion (x axis) and unfavourable cardiac events. Addition of SPECT perfusion imaging data adds highly significant value even with knowledge of age, sex, risk factors for coronary artery disease, ECG changes and presence or absence of chest pain. Adapted from Heller and colleagues.15

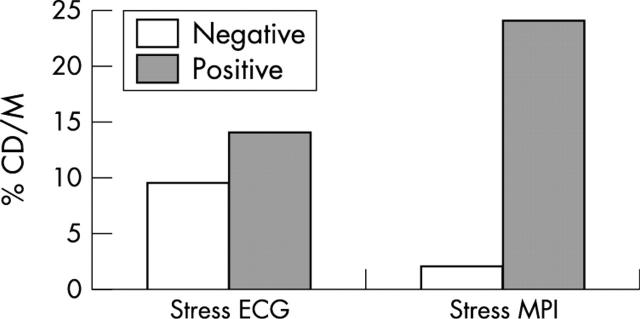

Figure 4.

Data supporting the use of MPI as the decision point in a conservative management strategy in patients with non-ST segment elevation ACS. The predictive value of stress MPI and stress electrocardiography (stress ECG) is shown in patients studied after initial stabilisation of UA with medical therapy. This figure summarises the results of three studies in which the incidence of cardiac death or non-fatal MI were assessed as end points (% CD/M on y axis) during follow up after stabilisation of UA. The presence of reversible perfusion defects reflective of ischaemia (positive stress MPI) was strongly predictive of cardiac events in this setting; the absence of inducible ischaemia on MPI (negative stress MPI) identifies a low risk group suggesting that such patients can be managed conservatively. Data are less consistent on the use of exercise electrocardiography in this setting. Adapted from Brown.33

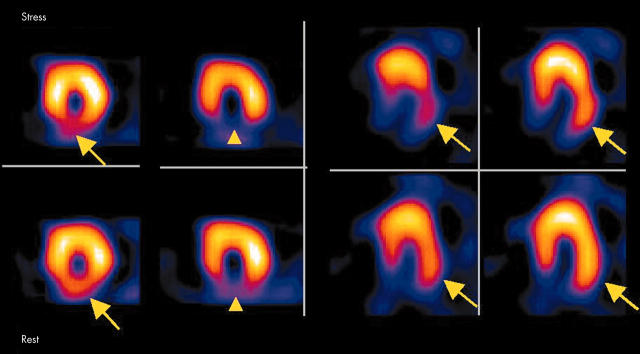

Figure 5.

Positive MPI study in a patient with medically stabilised UA. After presentation, symptoms were controlled with initial medical therapy, and stress MPI was performed. There is evidence of an inferobasal infarct (arrowhead) but the large extent of inducible ischaemia involving the inferoapical and lateral walls (arrows) suggests high risk for future events, and the patient was subsequently referred for catheterisation.

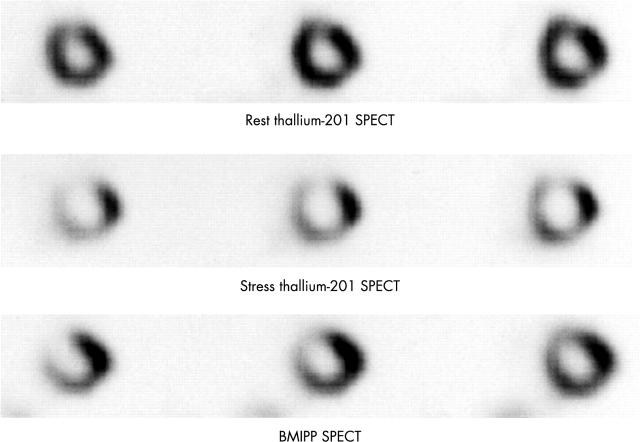

Figure 6.

Radiolabelled iodinated fatty acid analogue, BMIPP, used to assess fatty acid utilisation in the myocardium. In this example, the top row depicts normal resting perfusion by thallium 201 SPECT imaging, in short axis tomograms. The middle row demonstrates extensive stress induced thallium 201 perfusion abnormalities consistent with inducible ischaemia of the anterior, septal, and inferior walls. In the bottom row, the BMIPP SPECT images of the analogous short axis tomograms, obtained at rest, demonstrate ongoing abnormality in fatty acid metabolism in the anterior wall, septum and inferior wall, temporally distinct from the presenting ischaemic insult. Thus, this technique may provide risk stratification information based on the magnitude of abnormal fatty acid metabolism using rest imaging alone without the need for a stress test. This concept is currently under study. Adapted from Kawai and colleagues,39 images provided by Dr Nagara Tamaki, with permission.

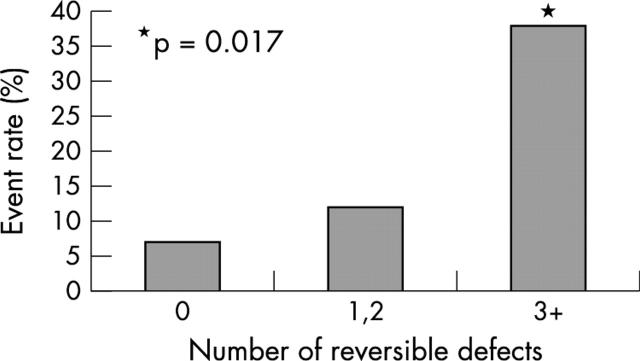

Figure 7.

Relation between the post-MI extent of ischaemia (as determined by the number of perfusion defects by SPECT Tc 99m sestamibi) with cardiac event rate (y axis). Patients with more extensive ischaemia are at progressively higher risk of unfavourable outcome (p = 0.017) compared with patients with no reversible defects. From Travin and colleagues.45

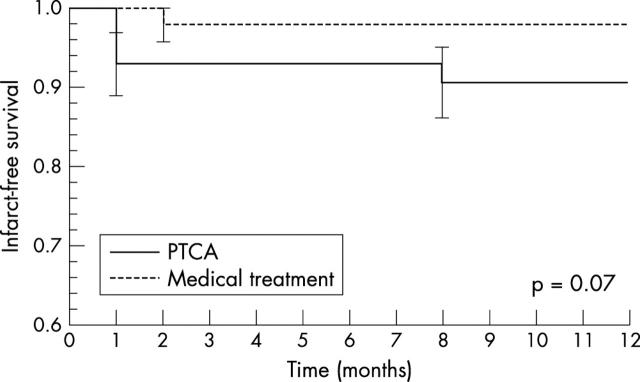

Figure 8.

In a study by Ellis and colleagues, patients who had received thrombolytic therapy for acute MI who had a residual stenosis of the infarct related artery but no inducible ischaemia in the infarct territory by MPI were randomised to either a strategy of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) of the residual stenosis or a strategy of no PTCA. Shown is a plot of actuarial freedom from cardiac events after randomisation to PTCA (solid line) or medical therapy (dashed line). There is no difference in outcome between the groups. Hence, identification of inducible ischaemia or lack thereof within the infarct zone by perfusion imaging after acute MI and reperfusion therapy can guide management decisions regarding revascularisation strategy. In the absence of any residual infarct zone ischaemia, there appears little benefit from a strategy of revascularisation. From Ellis and colleagues.49

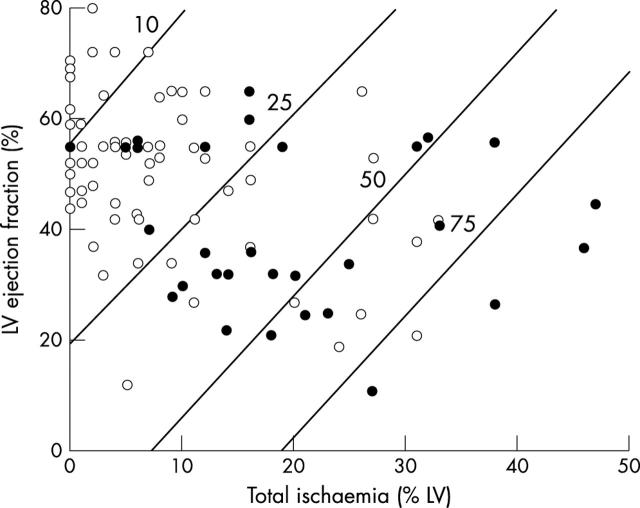

Figure 9.

Cox regression models displaying one year post-MI risk for cardiac event according to LV ejection fraction and total LV ischaemia. The diagonal lines are representative of isobars of per cent risk of event. Patient risk for any cardiac event increases as total LV ischaemia increases and LV ejection fraction decreases. LV ejection fraction and scintigraphic results for each of 92 patients who did (solid circles) or did not (open circles) have subsequent cardiac events over entire follow up period are plotted against calculated risk at one year. From Mahmarian and colleagues.46

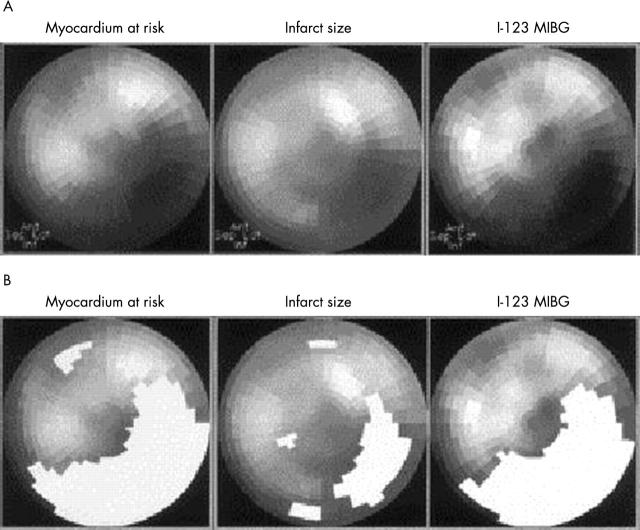

Figure 10.

Use of MIBG imaging of cardiac sympathetic innervation. In a study of acute MI patients, the territory of sympathetic denervation (MIBG defect, polar map images in right columns in panels A and B) corresponded more closely to the initial MI risk area (polar map images in left columns) than the final infarct size (polar map images in middle columns). From Matsunari and colleagues.60

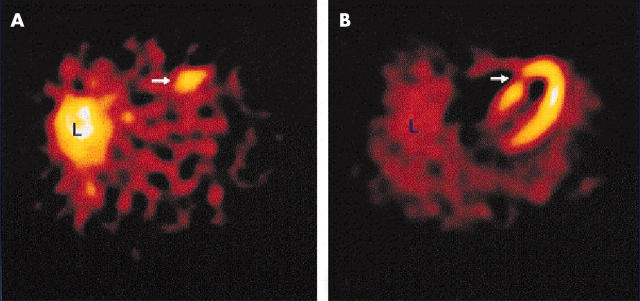

Figure 11.

Anteroseptal uptake of Tc 99m labelled annexin-V is seen (left panel) in the territory of a resting perfusion defect consistent with the infarct zone (right panel). Reprinted from Hofstra and colleagues,61 with permission.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antman E. M., Cohen M., Bernink P. J., McCabe C. H., Horacek T., Papuchis G., Mautner B., Corbalan R., Radley D., Braunwald E. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Paul G., Chen Shuo, Boden William E., Chow Bruce, Every Nathan R., Lavori Philip W., Hlatky Mark A. Cost-effectiveness of a conservative, ischemia-guided management strategy after non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of a randomized trial. Circulation. 2002 Feb 12;105(6):680–684. doi: 10.1161/hc0602.103584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Senior R., Raval U., Lahiri A. Superiority of nitrate-enhanced 201Tl over conventional redistribution 201Tl imaging for prognostic evaluation after myocardial infarction and thrombolysis. Circulation. 1997 Nov 4;96(9):2932–2937. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau L., Théroux P., Grégoire J., Gagnon D., Arsenault A. Technetium-99m sestamibi tomography in patients with spontaneous chest pain: correlations with clinical, electrocardiographic and angiographic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 Dec;18(7):1684–1691. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden W. E., O'Rourke R. A., Crawford M. H., Blaustein A. S., Deedwania P. C., Zoble R. G., Wexler L. F., Kleiger R. E., Pepine C. J., Ferry D. R. Outcomes in patients with acute non-Q-wave myocardial infarction randomly assigned to an invasive as compared with a conservative management strategy. Veterans Affairs Non-Q-Wave Infarction Strategies in Hospital (VANQWISH) Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jun 18;338(25):1785–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E., Antman E. M., Beasley J. W., Califf R. M., Cheitlin M. D., Hochman J. S., Jones R. H., Kereiakes D., Kupersmith J., Levin T. N. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary and recommendations. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (committee on the management of patients with unstable angina). Circulation. 2000 Sep 5;102(10):1193–1209. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. A., Heller G. V., Landin R. S., Shaw L. J., Beller G. A., Pasquale M. J., Haber S. B. Early dipyridamole (99m)Tc-sestamibi single photon emission computed tomographic imaging 2 to 4 days after acute myocardial infarction predicts in-hospital and postdischarge cardiac events: comparison with submaximal exercise imaging. Circulation. 1999 Nov 16;100(20):2060–2066. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.20.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. A. Management of unstable angina: the role of noninvasive risk stratification. J Nucl Cardiol. 1997 Mar-Apr;4(2 Pt 2):S164–S168. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(97)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon C. P., Weintraub W. S., Demopoulos L. A., Vicari R., Frey M. J., Lakkis N., Neumann F. J., Robertson D. H., DeLucca P. T., DiBattiste P. M. Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jun 21;344(25):1879–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian T. F., Clements I. P., Gibbons R. J. Noninvasive identification of myocardium at risk in patients with acute myocardial infarction and nondiagnostic electrocardiograms with technetium-99m-Sestamibi. Circulation. 1991 May;83(5):1615–1620. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakik H. A., Kleiman N. S., Farmer J. A., He Z. X., Wendt J. A., Pratt C. M., Verani M. S., Mahmarian J. J. Intensive medical therapy versus coronary angioplasty for suppression of myocardial ischemia in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Circulation. 1998 Nov 10;98(19):2017–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.19.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargie H. Myocardial infarction: redefined or reinvented? Heart. 2002 Jul;88(1):1–3. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S. G., Mooney M. R., George B. S., da Silva E. E., Talley J. D., Flanagan W. H., Topol E. J. Randomized trial of late elective angioplasty versus conservative management for patients with residual stenoses after thrombolytic treatment of myocardial infarction. Treatment of Post-Thrombolytic Stenoses (TOPS) Study Group. Circulation. 1992 Nov;86(5):1400–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.5.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkouh M. E., Smars P. A., Reeder G. S., Zinsmeister A. R., Evans R. W., Meloy T. D., Kopecky S. L., Allen M., Allison T. G., Gibbons R. J. A clinical trial of a chest-pain observation unit for patients with unstable angina. Chest Pain Evaluation in the Emergency Room (CHEER) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998 Dec 24;339(26):1882–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R. S., Watson D. D., Craddock G. B., Crampton R. S., Kaiser D. L., Denny M. J., Beller G. A. Prediction of cardiac events after uncomplicated myocardial infarction: a prospective study comparing predischarge exercise thallium-201 scintigraphy and coronary angiography. Circulation. 1983 Aug;68(2):321–336. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimple L. W., Hutter A. M., Jr, Guiney T. E., Boucher C. A. Prognostic utility of predischarge dipyridamole-thallium imaging compared to predischarge submaximal exercise electrocardiography and maximal exercise thallium imaging after uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1989 Dec 1;64(19):1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodacre S. W. Should we establish chest pain observation units in the UK? A systematic review and critical appraisal of the literature. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000 Jan;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal Abhinav, Samaha Frederick F., Boden William E., Wade Michael J., Kimmel Stephen E. Stress test criteria used in the conservative arm of the FRISC-II trial underdetects surgical coronary artery disease when applied to patients in the VANQWISH trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 May 15;39(10):1601–1607. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller G. V., Brown K. A., Landin R. J., Haber S. B. Safety of early intravenous dipyridamole technetium 99m sestamibi SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging after uncomplicated first myocardial infarction. Early Post MI IV Dipyridamole Study (EPIDS). Am Heart J. 1997 Jul;134(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller G. V., Stowers S. A., Hendel R. C., Herman S. D., Daher E., Ahlberg A. W., Baron J. M., Mendes de Leon C. F., Rizzo J. A., Wackers F. J. Clinical value of acute rest technetium-99m tetrofosmin tomographic myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with acute chest pain and nondiagnostic electrocardiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Apr;31(5):1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton T. C., Thompson R. C., Williams H. J., Saylors R., Fulmer H., Stowers S. A. Technetium-99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion imaging in the emergency room evaluation of chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Apr;23(5):1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90584-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra L., Liem I. H., Dumont E. A., Boersma H. H., van Heerde W. L., Doevendans P. A., De Muinck E., Wellens H. J., Kemerink G. J., Reutelingsperger C. P. Visualisation of cell death in vivo in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2000 Jul 15;356(9225):209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y., Tsukamoto E., Nozaki Y., Morita K., Sakurai M., Tamaki N. Significance of reduced uptake of iodinated fatty acid analogue for the evaluation of patients with acute chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 Dec;38(7):1888–1894. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klocke Francis J., Baird Michael G., Lorell Beverly H., Bateman Timothy M., Messer Joseph V., Berman Daniel S., O'Gara Patrick T., Carabello Blase A., Russell Richard O., Jr, Cerqueira Manuel D. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Oct 1;42(7):1318–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos M. C., Jesse R. L., Anderson F. P., Schmidt K. L., Ornato J. P., Tatum J. L. Comparison of myocardial perfusion imaging and cardiac troponin I in patients admitted to the emergency department with chest pain. Circulation. 1999 Apr 27;99(16):2073–2078. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoncini Mario, Sciagrà Roberto, Bellandi Francesco, Maioli Mauro, Sestini Stelvio, Marcucci Gabriella, Coppola Angela, Frascarelli Fabio, Mennuti Alberto, Dabizzi Roberto P. Low-dose dobutamine nitrate-enhanced technetium 99m sestamibi gated SPECT versus low-dose dobutamine echocardiography for detecting reversible dysfunction in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Cardiol. 2002 Jul-Aug;9(4):402–406. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2002.123856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppo J. A., O'Brien J., Rothendler J. A., Getchell J. D., Lee V. W. Dipyridamole-thallium-201 scintigraphy in the prediction of future cardiac events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1984 Apr 19;310(16):1014–1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404193101603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmarian J. J., Mahmarian A. C., Marks G. F., Pratt C. M., Verani M. S. Role of adenosine thallium-201 tomography for defining long-term risk in patients after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 May;25(6):1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00016-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Daniel B., Lee Thomas H. Conservative management of acute coronary syndrome: cheaper and better for you? Circulation. 2002 Feb 12;105(6):666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunari I., Schricke U., Bengel F. M., Haase H. U., Barthel P., Schmidt G., Nekolla S. G., Schoemig A., Schwaiger M. Extent of cardiac sympathetic neuronal damage is determined by the area of ischemia in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000 Jun 6;101(22):2579–2585. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi A. F., Khuri S., Deupree R. H., Sharma G. V., Scott S. M., Luchi R. J. Medical compared with surgical management of unstable angina. 5-year mortality and morbidity in the Veterans Administration Study. Circulation. 1989 Nov;80(5):1176–1189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T. J., Antman E. M., Brooks N. H., Califf R. M., Hillis L. D., Hiratzka L. F., Rapaport E., Riegel B., Russell R. O., Smith E. E., 3rd 1999 update: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary and Recommendations: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 1999 Aug 31;100(9):1016–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharir T., Germano G., Kavanagh P. B., Lai S., Cohen I., Lewin H. C., Friedman J. D., Zellweger M. J., Berman D. S. Incremental prognostic value of post-stress left ventricular ejection fraction and volume by gated myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 1999 Sep 7;100(10):1035–1042. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D. H., Stone P. H., Glynn R. J., Ganz D. A., Gibson C. M., Tracy R., Avorn J. Use of risk stratification to identify patients with unstable angina likeliest to benefit from an invasive versus conservative management strategy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 Oct;38(4):969–976. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhara B. S., Dudzic E., Basu S., Senior R., Lahiri A. Reverse redistribution of thallium-201 represents a low-risk finding in thrombolysed patients following myocardial infarction. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994 Oct;21(10):1094–1097. doi: 10.1007/BF00181064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers S. A., Eisenstein E. L., Th Wackers F. J., Berman D. S., Blackshear J. L., Jones A. D., Jr, Szymanski T. J., Jr, Lam L. C., Simons T. A., Natale D. An economic analysis of an aggressive diagnostic strategy with single photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging and early exercise stress testing in emergency department patients who present with chest pain but nondiagnostic electrocardiograms: results from a randomized trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000 Jan;35(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(00)70100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratmann H. G., Tamesis B. R., Younis L. T., Wittry M. D., Amato M., Miller D. D. Prognostic value of predischarge dipyridamole technetium 99m sestamibi myocardial tomography in medically treated patients with unstable angina. Am Heart J. 1995 Oct;130(4):734–740. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeishi Y., Sukekawa H., Fujiwara S., Ikeno E., Sasaki Y., Tomoike H. Reverse redistribution of technetium-99m-sestamibi following direct PTCA in acute myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 1996 Aug;37(8):1289–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum J. L., Jesse R. L., Kontos M. C., Nicholson C. S., Schmidt K. L., Roberts C. S., Ornato J. P. Comprehensive strategy for the evaluation and triage of the chest pain patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Jan;29(1):116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travin M. I., Dessouki A., Cameron T., Heller G. V. Use of exercise technetium-99m sestamibi SPECT imaging to detect residual ischemia and for risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995 Apr 1;75(10):665–669. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood S. R., Godman B., Salyani S., Ogle J. R., Ell P. J. Economics of myocardial perfusion imaging in Europe--the EMPIRE Study. Eur Heart J. 1999 Jan;20(2):157–166. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varetto T., Cantalupi D., Altieri A., Orlandi C. Emergency room technetium-99m sestamibi imaging to rule out acute myocardial ischemic events in patients with nondiagnostic electrocardiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Dec;22(7):1804–1808. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90761-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpi A., De Vita C., Franzosi M. G., Geraci E., Maggioni A. P., Mauri F., Negri E., Santoro E., Tavazzi L., Tognoni G. Determinants of 6-month mortality in survivors of myocardial infarction after thrombolysis. Results of the GISSI-2 data base. The Ad hoc Working Group of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-2 Data Base. Circulation. 1993 Aug;88(2):416–429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpi A., de Vita C., Franzosi M. G., Geraci E., Maggioni A. P., Mauri F., Negri E., Sontoro E., Tavazzi L., Tognoni G. Predictors of nonfatal reinfarction in survivors of myocardial infarction after thrombolysis. Results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI-2) Data Base. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Sep;24(3):608–615. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackers F. J., Lie K. I., Liem K. L., Sokole E. B., Samson G., van der Schoot J., Durrer D. Potential value of thallium-201 scintigraphy as a means of selecting patients for the coronary care unit. Br Heart J. 1979 Jan;41(1):111–117. doi: 10.1136/hrt.41.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younis L. T., Byers S., Shaw L., Barth G., Goodgold H., Chaitman B. R. Prognostic value of intravenous dipyridamole thallium scintigraphy after an acute myocardial ischemic event. Am J Cardiol. 1989 Jul 15;64(3):161–166. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaret B. L., Wackers F. J., Terrin M. L., Forman S. A., Williams D. O., Knatterud G. L., Braunwald E. Value of radionuclide rest and exercise left ventricular ejection fraction in assessing survival of patients after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) phase II study. The TIMI Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Jul;26(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00146-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]