Abstract

The term ‘evolutionary tinkering’ refers to evolutionary innovation by recombination of functional units, and includes the creation of novel proteins from pre-existing modules. A novel instance of evolutionary tinkering was recently discovered in the flowering plant genus Nicotiana: the conversion of a nuclear transcription factor into the plastid-resident protein WIN4 (wound-induced clone 4) involved in environmental stress responses. In this issue of the Biochemical Journal, Kodama and Sano now show that two steps are necessary for the establishment of the novel plastid protein: the acquisition of an internal translation initiation site and the use of multiple transcription starts to produce short mRNA variants that encode the plastid-targeted protein form.

Keywords: chloroplast, evolutionary tinkering, Nicotiana, protein evolution, transcription factor, transit peptide

Chloroplasts are of endosymbiotic origin and derive from a cyanobacterium-like progenitor. Although the chloroplast has retained a genome of its own, most genes of cyanobacterial origin have been transferred to the nucleus over evolutionary time, as the endosymbiont was transformed into a specialized organelle [1–3]. Strikingly, less than half of the approx. 4500 proteins of cyanobacterial origin now encoded in the nuclear genomes of plants are predicted to be located in chloroplasts, implying that a massive redistribution of cyanobacterium-derived proteins to other cellular compartments has occurred during evolution of the ‘green’ lineage [1,4]. Thus the endosymbiotic acquisition of cyanobacterial genes has led not only to the successful establishment of a new organelle, but also to substantial changes in the composition of the proteomes of the other compartments in the plant cell. Furthermore, the chloroplast proteome itself now includes a substantial set of proteins not derived from the endosymbiont [2,4]. Comparative analyses of the chloroplast proteomes of different plant species indicate that, although a core set of chloroplast proteins has been maintained, substantial divergence of chloroplast proteomes has occurred during the evolution of flowering plants, implying that species-related differences in organelle function exist [3].

The classical view of endosymbiotic gene transfer assumes that organellar genes translocated into nuclear chromosomes must acquire appropriate promoter sequences and sequences encoding N-terminal targeting signals (transit peptides) before they can express proteins that can find their way back to their organelle of origin [5]. Similarly, recruitment of a transit peptide is thought to be a prerequisite for the transformation of proteins not derived from cyanobacteria into chloroplast-targeted proteins. Indeed, several cases are known in which nuclear genes of organellar origin have obtained new transit peptide-coding sequences by duplication, recombination with other nuclear sequences and exon shuffling [2,5]. In this issue of the Biochemical Journal, an alternative mechanism for creating a cTP (chloroplast transit peptide) is elucidated by Kodama and Sano [6].

These authors reported previously that, during the evolution of the genus Nicotiana, the nuclear bHLH (basic helix–loop–helix) transcription factor WIN4 (wound-induced clone 4) has become a chloroplast protein. The NtWIN4 (Nicotiana tabacum WIN4) gene was identified in a screen for transcripts that accumulate after wound stress. NtWIN4 encodes a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 28–kDa which is homologous with bHLH-type transcription factors. When the full-length NtWIN4 protein was expressed from appropriate constructs, it was shown [by GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusion experiments] to be located in the cytosol and the nucleus, and to repress the transcription of a reporter gene [7]. Surprisingly, cell fractionation experiments revealed that in planta NtWIN4 is smaller (17–kDa) than expected, and is found only in chloroplasts [7]. Inspection of the 5′ segment of the NtWIN4 gene revealed the presence of an additional in-frame ATG codon downstream of the first. Use of this codon as the translation start site yields a 25–kDa protein. Subsequent analyses showed that an N-terminal segment of this form permits uptake into the chloroplast, and suggested that a cTP of 67 amino acids is removed after import into the organelle, resulting in the mature 17–kDa protein. The C-terminal portion of the predicted cTP overlaps with the DNA-binding domain of the bHLH motif. Removal of the cTP therefore presumably prevents the protein from serving as a transcription factor [7]. Transgenic tobacco plants that constitutively overexpress NtWIN4 show albinism and growth retardation, and they die prematurely. Plants in which NtWIN4 RNA levels were reduced by RNAi (RNA interference) appeared to be normal under non-stressed conditions, but showed delayed cell death when inoculated with pathogens. Based on these phenotypes and the observation that NtWIN4 transcripts are up-regulated in response to methyljasmonic acid, hydrogen peroxide, paraquat and pathogen attack, the authors concluded that NtWIN4 has been converted from a nuclear bHLH-type transcription repressor into a plastid-resident regulatory factor involved in defence against biotic and abiotic environmental stresses [7].

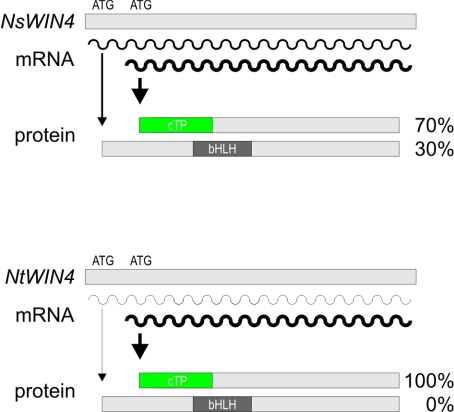

In this issue of the Biochemical Journal, Kodama and Sano elucidate the molecular alterations that led to this striking transformation in the genus Nicotiana [6]. N. tabacum is a natural amphidiploid (= allotetraploid) species that is thought to derive from two diploid progenitors, N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis. No WIN4 homologue could be amplified from N. tomentosiformis by PCR, whereas both WIN4 protein forms are immunologically detectable in N. sylvestris. Detailed inspection of WIN4 RNAs in N. sylvestris and N. tabacum revealed that patterns of transcription site usage differ between the two species, even though the N. sylvestris genome is apparently the only source of WIN4 transcripts in N. tabacum. Furthermore, individual variants are translated with different efficiencies in vitro. The prevalence in N. tabacum of short WIN4 transcripts that possess only the internal start codon, and their higher translation efficiency compared with the long mRNA variants coding for the full-length protein, are together sufficient to account for the predominance of the plastid WIN4 variant in this species (Figure 1). This mechanism of establishing a cTP at the cost of another protein module, in this case the bHLH motif, represents a new mode of protein evolution.

Figure 1. Mechanisms underlying the differential accumulation of distinct WIN4 transcripts and protein variants in N. sylvestris and N. tabacum.

The WIN4 transcript populations in N. sylvestris (NsWIN4) and N. tabacum (NtWIN4) are composed of several 5′-region variants. The relative abundance of long transcripts (with two AUG codons) and of short transcripts (with only the second AUG) in each species is indicated by the thickness of the curly lines which represent mRNAs. Translation initiation frequency is symbolized by the thickness of the arrows, and differs between species and mRNA variants: the first AUG is utilized more often in RNAs from N. sylvestris than from N. tabacum, whereas the second AUG is equally efficient in both species. This accounts for the differences in the relative amounts of the 28–kDa (targeted to the cytosol and the nucleus) and 25–kDa (targeted to the chloroplast) WIN4 forms in the two plant species. cTP, chloroplast transit peptide; bHLH, basis helix–loop–helix motif.

How widespread might this mechanism be? The Arabidopsis WIN4 homologue, At5g43650, is located in the nucleus and cytosol, as shown by GFP fusion experiments [7]. Although the At5g43650 protein can be relocated to the chloroplast when the first 30 amino acids are artificially removed [7], this cannot happen in planta because a second ATG is missing in the Arabidopsis thaliana gene. The possibility cannot be excluded that translation of a shorter At5g43650 variant could be initiated at a non-AUG codon, as described previously for other proteins [8], but the absence of an internal start codon in At5g43650 (and in WIN4 homologues from other species [7]) strongly suggests that the evolution of a plastid version of WIN4 is specific for N. tabacum. The existence of WIN4 homologues in Arabidopsis and rice makes it very likely that a WIN4-like protein also exists in N. tomentosiformis. Because it was not possible to detect a WIN4-like gene in N. tomentosiformis by PCR with NtWIN4-specific primers, its sequence must have diverged relative to its counterparts in N. tabacum and N. sylvestris, making it very likely that the N. sylvestris gene is indeed the progenitor of NtWIN4.

The biochemical functions of the nuclear and plastid WIN4 variants remain to be elucidated in detail in future experiments. The plastid version of WIN4 has apparently completely displaced the nuclear variant in N. tabacum; the function of the nuclear WIN4 version may be supplied by other transcription factors. In contrast, overexpression or down-regulation of the plastid version of WIN4 in N. tabacum affects plant performance, indicating that WIN4 is now required for optimal plastid function in this species. In this context, it will be interesting to investigate whether WIN4 is equally necessary for plastid function in N. sylvestris, and whether this role involves transcriptional regulation or a completely novel function.

Taken together, the findings of Kodama and Sano [6] add a new facet to the concept of evolutionary tinkering with genes and their products. François Jacob originally suggested that evolution works as a ‘tinkerer’ with already available parts, rather than as an engineer designing from scratch, so that novel genes or proteins are usually made from pre-existing components [9]. The repertoire of mechanisms for creating new nuclear genes now includes exon shuffling, gene duplication, retroposition, mobile element recruitment, gene fusion/fission, lateral gene transfer and de novo derivation from previously non-coding genomic regions [10]. NtWIN4 represents another variant of evolutionary tinkering: sacrificing of a functional domain, or at least a part of it, to generate an N-terminal targeting signal that directs the protein into another compartment. Future studies will have to clarify whether NtWIN4 represents a unique case or whether this mechanism has been successfully adopted in other cases and species.

References

- 1.Martin W., Rujan T., Richly E., Hansen A., Cornelsen S., Lins T., Leister D., Stoebe B., Hasegawa M., Penny D. Evolutionary analysis of Arabidopsis, cyanobacterial, and chloroplast genomes reveals plastid phylogeny and thousands of cyanobacterial genes in the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:12246–12251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182432999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leister D., Schneider A. Evolutionary contribution of plastid genes to plant nuclear genomes and its effects on composition of the proteomes of all cellular compartments. In: Hirt R. P., Horner D. S., editors. Organelle, Genomes and Eukaryote Phylogeny: An Evolutionary Synthesis in the Age of Genomics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 237–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richly E., Leister D. An improved prediction of chloroplast proteins reveals diversities and commonalities in the chloroplast proteomes of Arabidopsis and rice. Gene. 2004;329:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leister D. Chloroplast research in the genomic age. Trends Genet. 2003;19:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin W., Herrmann R. G. Gene transfer from organelles to the nucleus: how much, what happens, and why? Plant Physiol. 1998;118:9–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodama Y., Sano H. Functional diversification of a basic helix–loop–helix protein due to alternative transcription during generation of amphidiploidy in tobacco plants. Biochem. J. 2007;403:493–499. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kodama Y., Sano H. Evolution of a basic helix–loop–helix protein from a transcriptional repressor to a plastid-resident regulatory factor: involvement in hypersensitive cell death in tobacco plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35369–35380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen A. C., Lyznik A., Mohammed S., Elowsky C. G., Elo A., Yule R., Mackenzie S. A. Dual-domain, dual-targeting organellar protein presequences in Arabidopsis can use non-AUG start codons. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2805–2816. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob F. Evolution and tinkering. Science. 1977;196:1161–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.860134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long M., Betran E., Thornton K., Wang W. The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:865–875. doi: 10.1038/nrg1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]