Abstract

Adenosine-to-inosine editing in the anticodon of tRNAs is essential for viability. Enzymes mediating tRNA adenosine deamination in bacteria and yeast contain cytidine deaminase-conserved motifs, suggesting an evolutionary link between the two reactions. In trypanosomatids, tRNAs undergo both cytidine-to-uridine and adenosine-to-inosine editing, but the relationship between the two reactions is unclear. Here we show that down-regulation of the Trypanosoma brucei tRNA-editing enzyme by RNAi leads to a reduction in both C-to-U and A-to-I editing of tRNA in vivo. Surprisingly, in vitro, this enzyme can mediate A-to-I editing of tRNA and C-to-U deamination of ssDNA but not both in either substrate. The ability to use both DNA and RNA provides a model for a multispecificity editing enzyme. Notably, the ability of a single enzyme to perform two different deamination reactions also suggests that this enzyme still maintains specificities that would have been found in the ancestor deaminase, providing a first line of evidence for the evolution of editing deaminases.

Keywords: deaminases, evolution, hypermutation, modification, decoding

The use of up to 61 mRNA codons to specify 20 different amino acids is universally conserved among all organisms. Recognition of these codons by a smaller set of tRNAs is accomplished by the inherent base-pairing flexibility that exists between a tRNA's anticodon and its cognate codon, which often allows a single tRNA to decode multiple codons, as explained by the wobble rules postulated by Crick >40 years ago (1). Although codon–anticodon base-pairing flexibility can be achieved by the standard nucleotides found in RNA (e.g., G–U, U–G) as well as by modified nucleotides (2), the greatest relaxation in base-pairing ability is provided by the nucleoside inosine. Inosine at the first position of the anticodon permits recognition of three different nucleotides at the third codon position and as such leads to a net enhancement of the decoding capacity of a tRNA (3).

In Eukarya, a varying number of tRNAs (seven or eight, depending on the organism) are genomically encoded with an adenosine at the first position of the anticodon (position 34, the wobble base) (4). These tRNAs are able to decode the U-ending codons for the amino acids isoleucine, alanine, leucine, proline, valine, serine, arginine, and threonine but cannot decode their synonymous C-ending codons. These tRNAs must therefore undergo adenosine (A)-to-inosine-(I) editing at the wobble base to expand their decoding capacity (4). In Archaea, inosine is never found at the first position of the anticodon, and instead C-ending codons are read by genomically encoded G34-containing tRNAs that do not exist in the nuclear genomes of Eukarya (5). In Bacteria, A-to-I editing is restricted to a single tRNAArg; the other C-ending codons, as in Archaea, are read by G34-containing tRNAs (5). Therefore in both Eukarya and Bacteria, but not Archaea, conversion of adenosine to inosine in the wobble position of tRNA is essential for survival.

Editing enzymes that deaminate polynucleotides can be divided into two major families that can be distinguished by the characteristics of their metal-binding pocket: (i) the adenosine deaminases acting on RNAs (ADARs) and (ii) the polynucleotide cytidine deaminases (CDAs) acting on RNA (like the APOBEC family of enzymes) or DNA (like AID, the activation-induced deaminase). tRNA-editing adenosine deaminases [adenosine deaminases acting on tRNA (ADATs)] that target the anticodon belong to the CDA superfamily and harbor its characteristic H(C)XE and PCXXC metal-binding signature sequences (4, 6–10). Thus, although anticodon-specific ADATs structurally resemble CDAs, they modify adenosine, suggesting an evolutionary relationship between the two reactions.

We have shown previously that in trypanosomatids, tRNAThr(AGU) undergoes two different editing events in the anticodon loop: C-to-U editing at position 32 stimulates, but is not required for, the subsequent formation of inosine at position 34 (11). Whether this double editing is mediated by two different deaminases or one enzyme with dual function was not established. Given the proposed evolutionary link between members of the deaminase superfamily, we explored the possibility that ADATs can catalyze the deamination of both adenosine (A) and cytidine (C). We have examined the pathway for inosine formation at position 34 (first position of the anticodon) of tRNAThr(AGU) in trypanosomatids. Using a combination of RNAi and biochemical approaches, we demonstrate that one of the components of the tRNA A-to-I editing enzyme (TbADAT2) plays a role in both C-to-U and A-to-I editing in vivo, either by directly catalyzing both reactions or by playing a more indirect role in both pathways. Remarkably, in vitro, the recombinant enzyme, which is made up of two subunits (TbADAT2 and ADAT3), is able to deaminate specifically adenosines at the first position of the anticodon of tRNAs and can also perform C-to-U deamination reactions on DNA but not vice versa.

Results

The Core Domains of the ADATs Resemble CDAs.

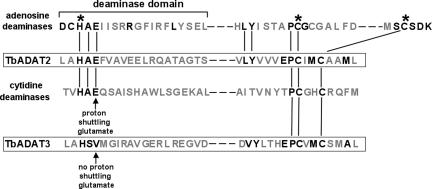

In yeast, the enzyme responsible for inosine formation at the first position of the anticodon of tRNAs has been characterized. This enzyme is a heterodimer formed by the association of ADAT2 and ADAT3, where ADAT2 is the catalytic subunit and ADAT3 serves only a structural role (4). Using the yeast sequences to perform database searches, we have identified two putative trypanosome homologs of the yeast ADAT enzyme (TbADAT2 and TbADAT3) [Fig. 1 and supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]. Previously, Gerber and Keller (4) suggested that A-to-I deaminases are derived from a gene duplication event of a precursor CDA base on the sequence similarity at their catalytic core. We have compared the core sequence of TbADAT2p and TbADAT3p with the conserved sequences of known deaminases (including nucleotide as well as editing deaminases). We found that the trypanosomatid deaminases also resemble C-to-U editing deaminases (Fig. 1) and contain the key residues shown to be essential for catalysis. These residues include the proton shuttling glutamate and the zinc-coordinating histidine and cysteine residues that play crucial roles in water activation and generation of the nucleophile involved in deamination (12–15).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of active-site core domains of the T. brucei tRNA-editing deaminase. The T. brucei sequences are compared with representative members of the cytidine and adenosine deaminase family. Although TbADATA2p and ADAT3p are required for adenosine deamination in tRNA, their active site resembles that of CDA. The figure shows the conserved residues shared by RNA editing adenosine and cytidine deaminases compared with tbtad2p and tbtad3p (boldface letters). Boxes, putative active sites of TbADAT2p and TbADAT3p. Asterisks, conserved residues involved in Zn2+ coordination found in all nucleotide- and RNA-editing deaminases. Arrows, absolutely conserved glutamate residue that is involved in proton shuttling during deamination; this residue is absent in tbtad3p, demonstrating that, as in yeast, tbtad3p may only serve a structural role in inosine formation. Vertical lines, shared conserved residues found in tbtad2p and CDAs. Diagonal line, altered position of one of the essential Zn2+ coordinating domains typical of RNA-editing adenosine deaminases.

RNAi of the TbADAT2 Leads to a Reduction in Both A-to-I and C-to-U Editing in Vivo.

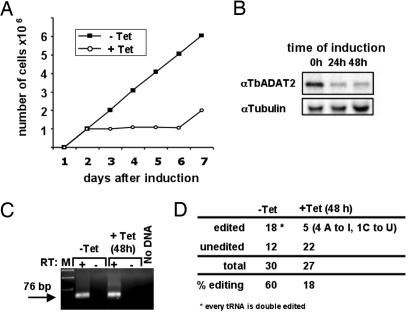

Given the possible evolutionary link between deaminases and our previous observation that a single tRNA in trypanosomatids can undergo two types of editing reactions, we have explored the possibility that the A-to-I enzyme could be able to mediate both types of editing reaction. We thus set out to study the role that the putative catalytic component of this enzyme (TbADAT2) plays in A-to-I editing. A portion of the coding sequence of TbADAT2 was cloned in a Trypanosoma brucei RNAi vector under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter (16). Independent T. brucei clones were grown in the presence or absence of tetracycline (Fig. 2A). In the presence of tetracycline, a growth phenotype was observed 48 h after induction, but uninduced T. brucei grew normally. Cells were collected at 0, 24, or 48 h after induction, and total protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TbADAT2 antibodies. An 8-fold reduction in the levels of TbADAT2 was observed in the induced samples compared with the tetracycline minus control (Fig. 2B). The reduction in signal correlated directly with the observed growth inhibition, indicating that this protein is essential for cell viability. This finding is supported by the observation that only one allele of the TbADAT2 gene (a single-copy gene) can be ablated by using standard gene-knockout technology; we failed to obtain viable cells in which both copies of the gene were disrupted (data not shown). To assess editing levels after RNAi, RT-PCRs were performed with total RNA isolated from induced cells (48 h) and the uninduced control. Primers specific for tRNAThr(AGU) were used as described, and specific products were purified, cloned, and sequenced (Fig. 2 C and D). The levels of A-to-I editing decreased as expected compared with the control. Surprisingly, the levels of C-to-U editing were also reduced. This experiment suggests that TbADAT2 is a key component of both the A-to-I and C-to-U editing activities in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Induction of RNAi against TbADAT2 causes a growth phenotype and reduces the levels of TbADAT2 within cells. (A) Effect of RNAi induction by tetracycline on T. brucei growth curve. (B) Western blot analysis with anti-TbADAT2 antibodies of whole cell extract. Extracts from +Tet cells were prepared 24 and 48 h after tetracycline addition to the growth medium. Anti-tubulin antibodies were used as control for protein levels. (C) Total RNA was isolated from the −Tet and +Tet (48 h after induction) cells for RT-PCR with tRNAThr(AGU)-specific primers. M, DNA size marker for electrophoresis. (D) RT-PCR products from C were purified and cloned into a plasmid vector, and independent clones were sequenced to assess editing levels.

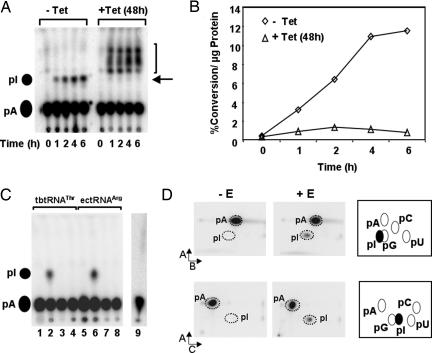

We then tested whole-cell extracts from T. brucei for in vitro A-to-I editing at different time points after RNAi induction. A time course in which radioactively labeled tRNAThr(AGU) substrate was incubated in the presence of extract showed wild-type levels of A-to-I editing activity in the uninduced control, but only negligible levels of editing activity were observed in extracts from cells grown in the presence of tetracycline (which induces RNAi) for 48 h (Fig. 3 A and B). A number of additional spots were observed in the TLC from the RNAi-induced extract, but their identity is currently unknown (Fig. 3A, bracket). Taken together, our data indicate that TbADAT2 is required for A-to-I editing. This conclusion is also supported by immunoprecipitation experiments, using TbADAT2-specific antibodies (SI Fig. 6), showing that immunoprecipitation with anti-TbADAT2 antibodies but not preimmune serum reduces editing activity in total cell extracts.

Fig. 3.

TbADAT2 is required for A-to-I editing of tRNAThr in T. brucei. (A) Whole-cell extracts from uninduced and induced [−Tet vs. +Tet (48h)] cells tested for in vitro A-to-I editing activity as described previously (11). tRNAThr(AGU) radiolabeled at every adenosine was incubated with protein fractions for increasing times. Reaction products were purified, digested with nuclease P1, and separated by TLC (11). Black circles, positions of 5′ inosine monophosphate (pI) and 5′ adenosine monophosphate (pA) markers for TLC (visualized by UV shadowing). Arrow, expected position for pI. Bracket, position of extra spots observed with the RNAi-induced extract; their significance is unknown. (B) Plot of the percent conversion at adenosine-34 per μg of protein vs. time from the +Tet (▵) and −Tet (48 h) (◇) cells. Specific conversion at A34 is calculated by normalizing the amount of radioactivity at A34 to the total number of label adenosines (n = 14), yielding a maximum theoretical value of 7.1% (11). (C) TLC analysis as in A but with recombinant TbADAT2/3 coexpressed in E. coli and purified through affinity- and size-exclusion chromatography. Lane 1, radioactive tRNAThr alone; lane 2, tRNA incubated with TbADAT2/3; lane 3, tRNAThr (A34 replaced by G34; a specificity control) incubated with TbADAT2/3; lane 4, tRNAThr incubated with recombinant EcADATa; lane 5, tRNAArg from E. coli (EctRNAArg) alone; lane 6, EctRNAArg incubated with recombinant EcADATa; lane 7, EctRNAArg (G34 specificity control) incubated with EcADATa; lane 8, EctRNAArg containing G34, alone; lane 9, tRNAThr(AGU) incubated with the recombinant TbADAT2(C136A)/ADAT3 mutant complex coexpressed in E. coli. (D) Two-dimensional TLC analysis of the reactions in lanes 1 and 2 from C to corroborate the identity of the pA and pI spots. Two different solvent systems were used as described (11). −E and +E refer to tRNAs incubated in the presence or absence of TbADAT2/3 enzyme as in C. The arrows and A and B refer to the different buffers system used (11). (Right) Expected migration of the different nucleotides according to published maps. Broken circles, positions of the different cold markers visualized by UV shadowing. pA, pC, pG, pU, and pI, 5′ nucleotide monophosphates for adenosine, cytosine, guanosine, and uridine, respectively.

Coexpression of the ADAT2 and ADAT3 Proteins Yields a Functional Editing Enzyme That Efficiently Performs A-to-I Editing of tRNAs.

To define further the A-to-I editing activity, recombinant TbADAT2 and TbADAT3 were coexpressed in Escherichia coli (SI Fig. 7), purified, and tested for in vitro editing. Even though these recombinant proteins could not support significant levels of editing when expressed and purified individually (SI Fig. 8 and data not shown), a complex containing both could readily edit A-to-I in tRNA (Fig. 3 C and D). The size of this complex (henceforth TbADAT2/3) was ≈210 kDa, as determined by size-exclusion chromatography. We found that TbADAT2/3 could efficiently edit A to I in tRNAThr (T. brucei) in vitro (Fig. 3C, lane 2, and Fig. 3D). To ensure that the enzyme is specific for A34, a mutant tRNA was also tested in which A34 was replaced by G34. This mutant is efficiently aminoacylated by the T. brucei threonyl tRNA synthetase, suggesting that its overall folding is still intact despite the mutation (11). This mutant, however, did not support any measurable editing activity (Fig. 3C, lane 3) with TbADAT2/3, demonstrating that A34 and no other adenosine in the tRNA is the target of editing. E. coli ADATa (EcADATa, the A-to-I deaminase from bacteria) is only able to deaminate E. coli tRNAArg (EctRNAArg), its natural substrate in bacteria, but no other tRNA (6). We found that recombinant EcADATa was only able to deaminate tRNAArg in vitro (Fig. 3C, lane 6) but was unable to use tRNAThr (from T. brucei) as a substrate (Fig. 3C, lane 4), discounting cross-contamination from the endogenous E. coli enzyme as a valid explanation for the results presented here. Finally, to demonstrate unequivocally that the TbADAT2 served as the catalytic moiety in the complex, we mutated its putative active site. We found that the catalytic mutant form of TbADAT2 (C136A) can still interact with TbADAT3 and that the mutant complex formed retains the gel filtration characteristics of the wild type, eluting with identical size. However, this active-site mutant complex was unable to catalyze A-to-I editing (Fig. 3C, lane 9). Taken together, our data demonstrate that TbADAT2, in complex with TbADAT3, is responsible for A-to-I editing in T. brucei. We also tested the complex for its ability to support C-to-U editing on tRNAThr (and its isoacceptors) but were unable to detect activity. We conclude that although TbADAT2 mediates C-to-U editing of tRNAThr in vivo (Fig. 2D), it cannot by itself or in association with TbADAT3 perform the reaction in vitro. We speculate that in vivo a modification in the endogenous substrate is absolutely necessary before C-to-U editing in tRNA. A direct precedent to this possibility exists in the case of A-to-I formation at position 57 of archaeal tRNAs, where adenosine-57 has to be first converted to m1A before deamination to form m1I (17, 18).

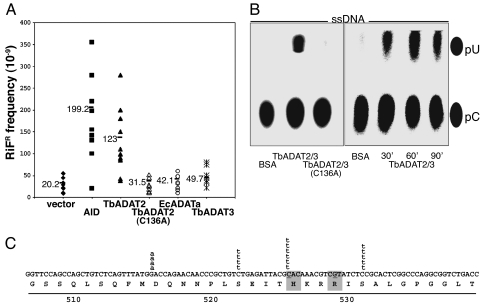

Recombinant ADAT2/3 Can Perform C-to-U Editing of DNA.

All functional polynucleotide CDAs analyzed to date mutagenize E. coli. For example, when an expression vector containing the cDNA of the polynucleotide CDA AID is transformed into uracil glycosylase (ung)-deficient E. coli (strain BH156), induction of AID expression increases the frequency of mutation in the rpoB gene, resulting in increased resistance to the drug rifampicin (ref. 19 and Fig. 4A). To confirm that TbADAT2 deaminates C to U, we cloned its cDNA in an anhydrotetracycline-inducible bacterial expression vector and measured the frequency of mutation to rifampicin resistance (RifR). We found that TbADAT2 increased mutation to RifR to levels comparable with those achieved by AID. In contrast, neither the vector control nor expression of a metabolic trypanosomatid CDA (TbCD09) (data not shown) nor overexpression of the EcADATa, nor overexpression of TbADAT3 had an effect on mutation frequency in ung-E. coli (Fig. 4A). In addition, the mutagenic activity of TbADAT2 depended on an intact catalytic site because an active-site mutant of TbADAT2 was unable to induce mutation in E. coli (C136A; Fig. 4A). Sequencing a number of independent clones confirmed that TbADAT2-mediated RifR colonies had mutated C–G base pairs (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, TbADAT2 displayed a sequence specificity that overlapped with, but was not identical to, that of AID.

Fig. 4.

TbADAT2 mutates deoxycytidine in E. coli and mediates C-to-U deamination in ssDNA. (A) Mutation frequencies for the rpoB gene in E. coli BH156 transformed with TbADAT2, hAID (a positive control), TbADAT2 (C136A, an active-site mutant), EcADATa (a bacterial ADAT), TbADAT3 alone, or empty vector. Each mark represents the frequency of mutation of an independent culture induced overnight with anhydrotetracycline (AHT); mean values are given for each expression vector. Mutation frequencies were calculated by scoring for the appearance of RifR colonies vs. total transformants. (B) Recombinant TbADAT2/3 or the TbADAT2(C136A)/ADAT3 complex was incubated with ssDNA, with every cytosine radioactively labeled. (Left) One-hour incubation. (Right) Time course for the indicated times. BSA, negative control where the ssDNA substrate was incubated with BSA. pC, pU, positions of cold 5′ cytosine monophosphate and 5′ uridine monophosphate markers visualized by UV. (C) Distribution of independent RifR mutations found in cells transformed with a TbADAT2 expression construct. The rpoB sequence from aa 507–539 is shown. Shaded boxes, preferred sites in AID-expressing cells; deaminated nucleotides are underlined. Lowercase letters, type of nucleotide change observed in each mutant. The nature of the Rif mutants was determined by directly amplifying and sequencing the relevant section of rpoB as described (19).

We then asked whether purified, recombinant TbADAT2/3 had CDA activity in vitro. Even though TbADAT2 could mediate C-to-U mutagenesis in DNA in vivo (Fig. 4A), we found that recombinant TbADAT2, by itself, was unable to deaminate C to U in ssDNA (data not shown). In contrast, the TbADAT2/3 complex showed significant CDA activity toward ssDNA (Fig. 4B; 30% deamination on average), which is higher than what has been reported for AID in vitro (20, 21). On the contrary, neither TbADAT3 (data not shown) nor the TbADAT2 (C136A) mutant (in complex with wild-type TbADAT3) could support any detectable deamination activity of ssDNA (Fig. 4B) or any editing of tRNAThr(AGU) in vitro (Fig. 3C, lane 9). Finally, the TbADAT2/3 had no measurable adenosine deaminase activity in ssDNA (data not shown). However, the possibility remains that the TbADAT2/3 complex can mediate DNA adenosine deamination in a sequence- or structure-specific fashion or in complex with additional accessory factors.

Discussion

Higher organisms use cytidine deamination as a mutagenic tool to catalyze or initiate a number of different reactions. In vertebrate cells, targeted deamination of DNA acts as a crucial trigger in immunity, initiating both antibody diversification (by deamination of cytidine residues within the Ig locus) and antiviral responses (by deamination of cytidine residues within the DNA of viral replication intermediates) (22–25). Finally, targeted deamination of mRNA is important for gene regulation (26–29).

In vertebrate cells, the family of CDAs that mediate the targeted mutagenesis of polynucleic acids is referred to as the AID/APOBEC family. All proteins in this family act on cytidine in ssDNA or RNA. However, each protein acts on a specific substrate and within that substrate, displays a signature preference with regard to the identities of the specific cytidine residues targeted. In fact, on their specific substrates, AID/APOBECs recognize their preferred cytidines in a trinucleotide context, reminiscent of the way tRNA-adenosine deaminases recognize the targeted adenosine within the trinucleotide context of the anticodon. In part because of this similarity, the possibility has recently been raised that polynucleotide CDAs have evolved from tRNA-editing enzymes (30).

To explore the possibility that polynucleotide cytidine deamination is evolutionarily linked to tRNA editing at adenosine residues, we turned to trypanosomatids where C-to-U editing in tRNA has been observed (11, 31, 32). Indeed, we have found that a single enzymatic complex in T. brucei (TbADAT2/3) can perform both C-to-U deamination of ssDNA and A-to-I deamination of tRNA in vitro and that one of its two subunits (TbADAT2) is directly involved in catalyzing both of these reactions. Therefore, one enzyme can catalyze both cytidine and adenosine deamination, albeit on different substrates, offering a snapshot of the evolutionary path taken by this family of enzymes and leading to the advent of DNA- and mRNA-editing deaminases.

Adenosine editing in trypanosomatid tRNA is absolutely required for survival; however, the relevance of a ssDNA CDA for the lifecycle of T. brucei is less clear. We speculate that the mutagenic activity of TbADAT2/3 may be related to the mechanism of antigenic variation. Indeed, deaminase-initiated class switch recombination in the Ig locus in vertebrate cells and gene conversion in the expressed variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) locus in T. brucei are very similar in mechanistic requirements: both loci are telomeric, both are flanked by highly repetitive regions, and in both cases recombination is facilitated by transcription (33–36). However, whether cytidine deamination within DNA is important for VSG switching and antigenic variation in T. brucei remains to be determined.

Taken together, our experiments demonstrate that TbADAT2 is a multifunctional enzyme with sufficient flexibility to mediate both types of deamination reactions, albeit on different substrates. This flexibility might be an inherent characteristic of the ancestral deaminase domain. Substrate specificity would have evolved by appending this flexible catalytic module to different protein scaffolds. At the same time, possible interaction with ancillary factors and/or the subcellular localization of the enzyme itself would have kept this potentially rampant mutagenic activity in check.

The activity described here provides a model for the regulation of deaminase specificity on various substrates. It also raises the possibility that members of the polynucleotide CDA superfamily may mediate A-to-I editing of their appropriate substrates in vivo. In this regard, it is tempting to speculate that should AID, the enzyme mediating somatic hypermutation of Ig genes, have retained such an activity, it could catalyze both dC-to-dT and dA-to-dG changes, thus directly providing for the entire spectrum of mutations recovered from Ig genes (37).

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs and Recombinant Protein Expression.

The genes encoding ADAT2 and ADAT3 were cloned from T. brucei cDNA into the SalI/NotI and NdeI/XhoI sites of the pCDFduet-1 expression vector (Novagen, EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) respectively. The final CDF-ADAT2/3 construct encodes T. brucei ADAT2 with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and T. brucei ADAT3 with a C-terminal FLAG tag. This vector was then transformed into BL21 DE3 PLys cells. A 10-ml overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 liter of LB supplemented with spectinomycin. Cells were grown to an A600 of 0.8 at 37°C, at which point the temperature was lowered to 22°C, and the cells were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG overnight. Cells were harvested, suspended in lysis buffer (200 mM KCl/20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9) and lysed in an Emulsiflex C5 homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was applied to a TALON Superflow affinity resin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Protein was eluted by using a step gradient of lysis buffer containing 15–250 mM imidazole. ADAT2/3-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed against lysis buffer overnight, concentrated, and further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Active complex fractions eluted with a peak at 212 kDa.

Deamination Assays, RT-PCRs, and Mutation Analysis.

Cytidine deamination was assayed by incubating ssDNA probe (body-labeled on cytidine with [32P]dCTP) with recombinant ADAT2/3 in reaction buffer (40 mM Tris, pH 7.9/6 mM MgCl2/10 mM DTT) at 37°C. Reactions were then extracted with phenol, and ssDNA was precipitated. After centrifugation, the resulting pellet was suspended in P1 nuclease buffer (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and was incubated with P1 nuclease (0.5 unit per reaction) at 37°C for at least 12 h. One microliter of each reaction was spotted onto a cellulose TLC plate (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ). The TLC plate was then developed in a solvent containing H2O/12.1 M HCl/isopropyl alcohol (10:20:70 vol/vol). After drying, the TLC plate was imaged by using a Typhoon PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Adenosine deamination assays were performed as described previously (11). RT-PCRs to score the number of edited clones were as described previously (11, 31). Mutation frequencies for rpoB-mediated resistance to rifampicin were as described elsewhere (19).

Trypanosome Cell Lines and Plasmid Construction.

T. brucei bloodstream forms (strain Lister 427, antigenic type MITat 1.2, clone 221a (38) were cultured in HMI-9 medium at 37°C (39). This strain had been manipulated to generate the bloodstream and procyclic cell lines “single marker” and 29-13, respectively (40), which constitutively express T7 RNA polymerase and the Tet repressor. Bloodstream forms were cultured in HMI-9 medium containing 2.5 μg/ml G418 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Procyclic forms were cultured in SDM-79 medium containing 15 μg/ml G418 and 25 μg/ml hygromycin. To generate ADAT2 RNAi cell lines, the 3′ part of the ORF was amplified and cloned into AhdI-digested p2T7TA-blue plasmid (16). Constructs were linearized with NotI and stably transfected. All transfections were performed as described previously (40).

Acknowledgments

We thank Gregory Verdine (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) for EcADATa (TadA) expression constructs. We also thank Eva Besmer, Michael Ibba, Henri Grosjean, Jesse Rinehart, Venkat Gopalan, Erec Stebbins, and all members of the F.N.P. and J.D.A. laboratories for helpful comments and discussions.

Abbreviations

- ADAT

adenosine deaminase acting on tRNA

- AID

activation-induced deaminase

- CDA

cytidine deaminase

- RifR

rifampicin resistance.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702394104/DC1.

References

- 1.Crick FH. J Mol Biol. 1966;19:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agris PF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:223–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran JF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:683–688. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber AP, Keller W. Science. 1999;286:1146–1149. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprinzl M, Vassilenko KS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D139–D140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf J, Gerber AP, Keller W. EMBO J. 2002;21:3841–3851. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias Y, Huang RH. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12057–12065. doi: 10.1021/bi050499f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuratani M, Ishii R, Bessho Y, Fukunaga R, Sengoku T, Shirouzu M, Sekine S, Yokoyama S. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16002–16008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosjean H, Edqvist J, Straby KB, Giege R. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:67–85. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auxilien S, Crain PF, Trewyn RW, Grosjean H. J Mol Biol. 1996;262:437–458. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubio MA, Ragone FL, Gaston KW, Ibba M, Alfonzo JD. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:115–120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AA, Carlow DC, Wolfenden R, Short SA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6468–6474. doi: 10.1021/bi00187a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betts L, Xiang S, Short SA, Wolfenden R, Carter CW., Jr J Mol Biol. 1994;235:635–656. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navaratnam N, Fujino T, Bayliss J, Jarmuz A, How A, Richardson N, Somasekaram A, Bhattacharya S, Carter C, Scott J. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:695–714. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott J, Navaratnam N, Carter C. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:791–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alibu VP, Storm L, Haile S, Clayton C, Horn D. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;139:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Droogmans L, Roovers M, Bujnicki JM, Tricot C, Hartsch T, Stalon V, Grosjean H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2148–2156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roovers M, Wouters J, Bujnicki JM, Tricot C, Stalon V, Grosjean H, Droogmans L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:465–476. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen-Mahrt SK, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. Nature. 2002;418:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhuri J, Tian M, Khuong C, Chua K, Pinaud E, Alt FW. Nature. 2003;422:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nature01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bransteitter R, Pham P, Scharff MD, Goodman MF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4102–4107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conticello SG, Thomas CJ, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:367–377. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris RS, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Malim MH, Neuberger MS. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:641–643. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuberger MS, Harris RS, Di Noia J, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:305–312. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris RS, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gott JM, Emeson RB. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:499–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanc V, Davidson NO. J Biol Chem. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaub M, Keller W. Biochimie. 2002;84:791–803. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rueter SM, Burns CM, Coode SA, Mookherjee P, Emeson RB. Science. 1995;267:1491–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.7878468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conticello SG, Langlois MA, Neuberger MS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:7–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfonzo JD, Blanc V, Estevez AM, Rubio MA, Simpson L. EMBO J. 1999;18:7056–7062. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio MAT, Alfonzo JD. Topics Curr Genet. 2005;12:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCulloch R, Rudenko G, Borst P. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:833–843. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cross GA, Wirtz LE, Navarro M. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pays E, Vanhamme L, Perez-Morga D. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dreesen O, Li B, Cross GA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:70–75. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franklin A, Blanden RV. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doyle JJ, Hirumi H, Hirumi K, Lupton EN, Cross GA. Parasitology. 1980;80:359–369. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirumi H, Hirumi K. J Parasitol. 1989;75:985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirtz E, Leal S, Ochatt C, Cross GA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]