Abstract

We used dense-array EEG to study the neural correlates of selective attention to specific features of objects that spatially overlapped an unattended image. Participants viewed superimposed images (horizontal and vertical bars differing in color) and attended to one image to identify bar width changes in specific locations. Images were frequency tagged so attention directed to unique parts of the stimuli could be tracked. Steady-state visual evoked potentials were used to quantify attention-related neural activity. As expected, selectively attending to specific parts of the attended image enhanced brain activity related to the attended element, and left unchanged activity elicited by spatially overlapping unattended stimuli. Under specific conditions, however, we found increased activity to unattended stimuli. The specificity of the selective attention effects presented herein, however, may be limited under certain complex stimulus conditions.

Visual attention supports the ability to focus on relevant aspects of the visual environment. In particular, selective attention is responsible for enhancing perception of specific stimulus properties such as location, size, color, etc., at specific times (Driver & Frackowiak, 2001; Kastner & Pinsk, 2004). Several authors have proposed that visual selective attention is mediated by neural amplification of cell populations encoding the to-be-attended stimulus (e.g. Hillyard & Anllo-Vento, 1998; Kastner & Pinsk, 2004). In the realm of spatial selective attention, amplitude modulation of activity in neuron populations coding for particular spatial locations is regarded as a simple and effective means for achieving optimized processing at attended locations (Driver & Frackowiak, 2001). With increasing complexity of the visual array under consideration, however, additional processes are required to resolve ambiguity and efficiently direct resources to the task-relevant stimulus. For instance, in situations where attended and unattended stimuli overlap spatially, knowledge of spatial location may be insufficient for separating targets from non-targets (e.g. when trying to detect a white-tailed deer in a thick stand of trees in late fall). In these cases, additional processes such as feature- or object-based selection are required to successfully and correctly identify the visual scene (e.g., Pei, Pettet, & Norcia, 2002; Valdes-Sosa, Bobes, Rodriguez, & Pinilla, 1998). In the laboratory, these kinds of selective attention have been examined using sequentially presented stimuli differing along one or more distinct feature dimensions (i.e. color, size, orientation, etc.). Given the close conceptual relationship between object features and objects defined by distinct features, there has been debate about how feature- versus object-based attention can be independently examined. On the level of brain processes, one common finding has been that large-scale neural activity is reliably enhanced as a function of attentional allocation to visual features (Müller & Keil, 2004), objects (Valdes-Sosa et al., 1998), or spatial locations (Morgan, Hansen, & Hillyard, 1996).

An aspect of this problem that has been rarely studied is the role of selective attention to specific features for resolving visual objects that overlap in space and in time, although this is close to the requirements during most activities of daily life. Valdes-Sosa and colleagues (Rodriguez, Valdes-Sosa, & Freiwald, 2002; Valdes-Sosa et al., 1998) have used this method of overlapping stimuli with success for examining the neural correlates of space and object-based attentional mechanisms. Chen, Seth, Gally, & Edelman (2003) also evaluated the specificity of selective attention to an attended image that spatially overlapped an unattended image. They measured the strength of steady-state visual evoked responses (ssVEPs) to horizontal and vertical gratings (one of which was attended, each image oscillating at its own specific frequency) in 11 participants under broad and narrow attention conditions. There was greater neural activity for the attended relative to the unattended image under the broad attention condition, but paradoxically lower activity for the attended relative to the unattended image in the narrow attention condition. Chen et al. (2003) proposed the functioning of an inhibitory mechanism under the narrow attention condition. Their design prevented them from evaluating changes in the locus of attention within the attended image as a function of broad and narrow attention. Measuring changes in neural activity to different parts of the attended image under broad and narrow attention conditions would more specifically address whether an inhibitory mechanism accounted for the Chen et al. (2003) results.

The ssVEP, a useful index of neural activity, is a response of visual cortex to flickering stimuli, where the frequency of brain response tends to equal the flicker rate of the stimuli. Four advantages of the ssVEP for present purposes are that (i) the experimenter can select the flicker rate (frequency) of the intensity-modulated stimulus, and stimulus-driven evoked power changes take place at the fundamental frequency of the flicker rate (Regan, 1989), (ii) ssVEPs are characterized by high signal-to-noise ratios (Mast & Victor 1991), and, in contrast to VEPs where changes occur in a wide frequency range, changes in ssVEPs occur at a known, single frequency of interest, (iii) strength of the ssVEP is easily quantified using Fourier analysis, and (iv) multiple stimuli flickering at different frequencies can be presented simultaneously to the visual system, so attention to independent objects and spatial locations can be tracked (Morgan et al., 1996; Müller & Hübner, 2002; Müller, Malinowski, Gruber, & Hillyard, 2003; Regan & Regan, 2003).

Steady-state stimulus delivery has facilitated knowledge acquisition in a variety of areas. For instance, steady-state responses are sensitive to attention manipulations (Morgan, et al. 1996; Müller & Hillyard 2000; Müller & Hübner 2002; Müller, et al. 1998), the emotional content of stimuli (Keil, et al. 2003; Keil, et al. 2005; Moratti and Keil 2005; Moratti, et al. 2006; Moratti, et al. 2004), and tonic changes in brain state (Picton, et al. 1987; Plourde & Picton 1990; Silberstein, et al. 1990). Attention-related changes in N1 ERP amplitudes also correlate with attention-related modulations of ssVEP amplitudes, suggesting a functional link between these two measures (Müller & Hillyard 2000).

In the present studies, superimposed visual images (Chen et al., 2003) were used to investigate the neural correlates of selective attention (specifically color selection) for an attended stimulus that spatially overlapped an unattended stimulus differing in color. The ssVEP was used to quantify the large-scale neural correlates of selective attention (Morgan et al., 1996). To take full advantage of the ssVEP for studying attentional selection, the present design allowed for measuring changes in the locus of attention within the attended image (by using multiple unique frequency tags) as a function of broad and narrow attention. By virtue of variations in stimulus conditions, we also evaluated the interaction between attentional selection and the size of the to-be-attended area. Thus, changes in attention demands within an attended visual object could be studied in addition to evaluating differences in neural activity between attended and non-attended objects.

Method

Participants

Three experiments comprise this study. All experiments had 12 participants (Experiment 1: 7 males, ages 18–26 years; Experiment 2: 7 males, ages 18–21 years; Experiment 3: 9 males, ages 18–22 years), all of whom participated in only one experiment. Participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, had no evidence of neurological impairment, were free of psychiatric or substance use disorders (by self-report), and were given class credit for their participation. The UGA Institutional Review Board approved this study and participants provided informed consent prior to testing.

Stimuli and Procedure

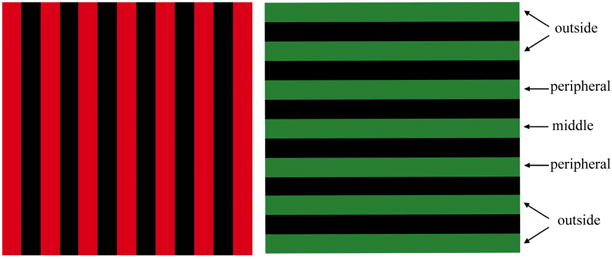

Visual stimuli consisted of two superimposed images (Figure 1; Chen et al., 2003). Both the horizontal and vertical images were composed of equally spaced parallel bars of 1 deg of visual angle that were equal in luminance (5.5 cd/m2 against a 0.1 cd/m2 background). One image was red and the other was green. A centrally-located dim grey dot, on which participants fixated, was visible throughout testing. Stimuli were presented on a 21″ high-resolution flat surface color monitor with a refresh rate of 100 Hz that was 60 cm from the participants’ eyes.

Figure 1.

The two images (horizontal and vertical bars) used in these experiments are shown as spatially distinct, but they perfectly overlapped during testing. For the 7-bar study, both images were presented as they are shown here. For the 3-bar study, only the three middle bars of each image were presented to the participants (i.e. the middle bars and the peripheral bars). For the 5-bar study, only the five middle bars of each image were presented to the participants (i.e. the middle bars, the peripheral bars, and the outside bars that were immediately adjacent to the peripheral bars).

The three experiments differed in the total number of horizontal and vertical bars used to drive the visual system (see Figure 1). In Experiment 1, each image was 13 deg square and consisted of 7 colored bars (one middle bar, two peripheral bars, and four outside bars - two on each side). In Experiment 2, each image was 5 deg square and consisted of 3 colored bars (one middle bar and two peripheral bars). In Experiment 3, each image was 9 deg square and consisted of 5 colored bars (one middle bar, two peripheral bars, and two outside bars - one on each side).

In all experiments, either the horizontal or vertical bars were identified as the to-be-attended image throughout 2-minute trial blocks (Chen et al., 2003). For the attended image, subjects were to identify width changes (30% increase or decrease) in either any of the three middle bars (attend-all condition) or in the center middle bar alone (attend-mid condition). The attentional manipulation, therefore, allowed for comparisons between broad and narrow attention, like in the Chen et al. (2003) study, as opposed to simply comparing attend and unattend conditions. During each trial block, any of the three middle bars in either the attended or unattended image was randomly and independently selected for a width change. Width changes lasted for ≈400 msec before the bar returned to its original size; the interval between width changes was randomly selected from a 1–3 sec rectangular distribution. Subjects were to respond to target events with a button press.

An important requirement when using the “method of multiple stimuli” (Regan & Regan, 2003) is that the tag frequencies be close enough that their differences are undetectable to the observer, differences between them are irrelevant to the sensory system under investigation, and that the different frequencies are not harmonically related. In this study, the tag frequencies, which were created by flashing the figure for one refresh and then varying the number of blank refreshes between flashes, were all within a 1.66 Hz range (6.67 to 8.33 Hz). This has the additional advantage of minimizing possible confounds between attention modulation and tagging frequency (cf., Ding, Sperling, & Srinivasan, 2006).

For the 7-bar experiment, each image (all seven bars) flickered in unison at a unique frequency, either 7.14 Hz or 8.33 Hz. Using these stimuli, like in Chen et al. (2003), strength of attention to the attended and unattended images could be quantified, but determining whether attention shifted within the attended image depending on condition (attend-all versus attend-mid) was not possible. For the 3-bar and 5-bar experiments, the attended image had bars flickering at different frequencies. In the three bar experiment, the middle bar of the attended image always flickered at 7.69 Hz, but the peripheral bars of the attended image and the whole unattended image flickered at either 7.14 Hz or 8.33 Hz. The flicker rates in the 5-bar experiment were the same as those in the 3-bar experiment, except that the outside bars of the attended image also flickered at the unique frequency of 6.67 Hz. For these experiments, whether and how attention shifted within the attended image depending on condition (attend-all versus attend-mid) could be determined. Exactly as in the Chen et al. (2003) study, the order of trial block presentations was counterbalanced by color of attended bars (red or green), direction of attended bars (horizontal or vertical) and frequency of the unattended image (7.14 or 8.33 Hz). For each condition (attend-all, attend-mid), therefore, eight 2-minute trial blocks were completed by each participant.

EEG Recording

EEG data were measured using a 256-channel Geodesic Sensor Net and NetAmps 200 amplifiers (Electrical Geodesics Inc.; EGI, Eugene, OR). Recordings were referenced to the vertex sensor (Cz). Electrode impedances were below 50 kΩ and data were analogue filtered from 0.1–100 Hz. Data were digitized at 250 Hz, stored on disk for subsequent off-line analysis, and recorded continuously throughout 2 min trial blocks.

Data Analysis

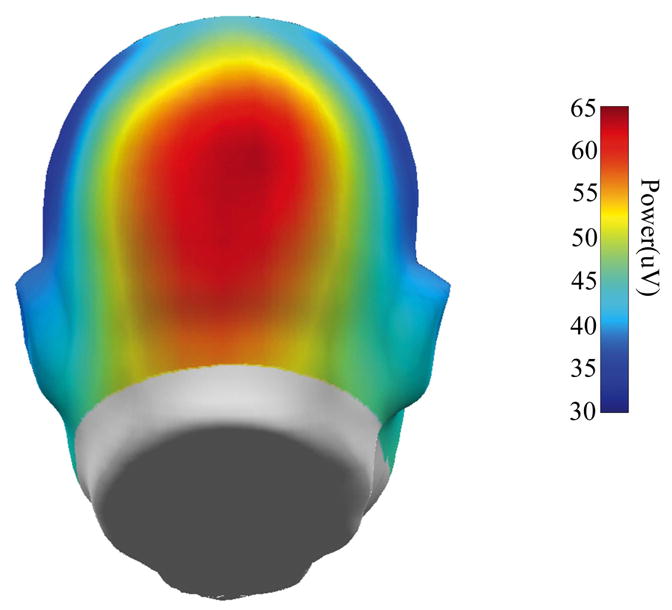

Raw data were checked for bad channels (less than 5% for any participant), which were replaced using a spherical spline interpolation method (as implemented in BESA 5.0). Data were transformed to an average reference and digitally filtered from 2–40 Hz (6db/octave rolloff, zero phase). To ensure that steady state had been adequately established, we quantified selective attention using only the last 100 sec of each 120 sec trial block. The 100 sec window yields 0.01 Hz resolution, which was necessary to quantify neural response magnitudes at the specific oscillation frequencies used in the present experiments. Before computing FFT power, the mean and linear trends were removed (using MATLAB) for each EEG channel. Figure 2 shows a head surface map of FFT power, collapsing over all frequencies and all conditions, averaged over all participants. Maximum ssVEP power was localized at midline sensors, over visual cortex. There was no other peak of activity associated with the ssVEP at any other spatial location. Indeed, given the size and complexity of the stimuli used here, and the fact that 100 sec blocks were necessary to capture the tag frequencies, it is not surprising that the majority of the ssVEP signal recorded at the scalp would be limited in extent and come from the vicinity of visual cortex (see, e.g., Di Russo et al., 2006; Pastor, Artieda, Arbizu, Valencia, & Masdeu, 2003). FFT power at the frequency of stimulation averaged over 67 EEG sensors that captured the maximal signal, therefore, was used to quantify strength of selective attention (see Figure 3 for an example). Phase and background power values (i.e. from 6.5–8.5 Hz, excluding the tag frequencies) were also quantified, but there were no significant attention effects on these variables, so they are not considered further.

Figure 2.

Head surface map of grand average FFT power to the steady-state stimuli (averaged over all frequencies and all conditions for all participants).

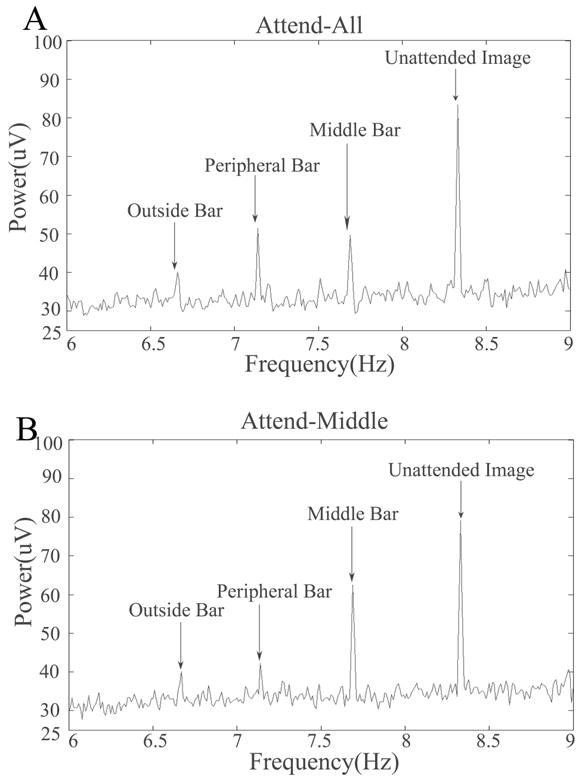

Figure 3.

An example of power spectra averaged over the 67 EEG channels that captured the peak ssVEP power averaged over all participants for the 5-bar experiment. In this example, the green vertical middle bar, peripheral bars, and outside bars flickered at 7.69 Hz, 7.14 Hz, and 6.67 Hz, respectively. The red horizontal bars flickered at 8.33Hz. Participants attended to the green vertical bars, and were asked to identify width changes in the green middle and peripheral bars (A, the attend-all condition) or green middle bar only (B, the attend-mid condition).

Results

Behavioral Responses

Correct responses were button presses happening 100–1000 msec after target onset (bar width change). An Experiment (7-bar, 3-bar, 5-bar) by Attention Condition (attend-all, attend-mid) repeated-measures ANOVA (with Huyhn-Feldt adjusted degrees of freedom) was used to test for differences on d-prime and correct response reaction times. For d-prime, there was a significant effect of Attention Condition, F(1,33)=185.4, p<.001, with participants being better at detecting target events during the attend-mid (M=2.34, SE=0.10) than the attend-all condition (M=1.25, SE=0.07). For reaction times, there also was a significant effect of Attention Condition, F(1,33)=15.4, p<.001. Participants responded faster to targets in the attend-mid (582.5 ms, SE=9.4) than the attend-all condition (607.3 ms, SE=8.4). These effects did not differ across studies.

Brain Activity

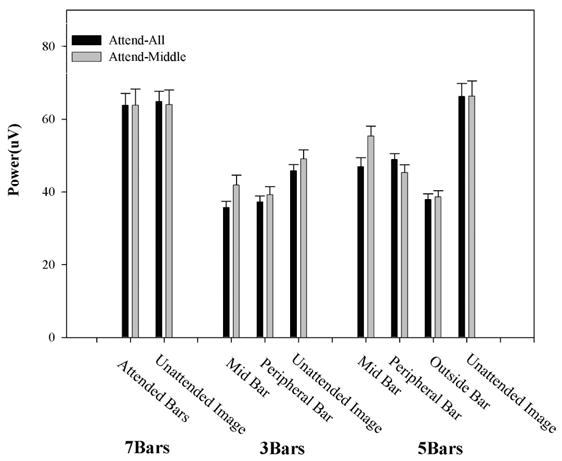

Attention Condition by Object repeated-measures ANOVAs (with Huyhn-Feldt adjusted degrees of freedom) were used to test for differences on ssVEP power within each experiment (see Figure 4). For the 7-bar experiment, there were no significant effects on ssVEP power. For the 3-bar experiment, there was a significant effect of Attention Condition on ssVEP power, F(1,11)=10.2, p=.009. The Attention Condition by Object (middle bar, peripheral bar, unattended image) interaction was not significant, F(2,22)=2.1, p=.160, ε=.811. The ssVEP power, therefore, was larger for all stimuli under the attend-mid condition (see Figure 4) in the 3-bar study. For the 5-bar study, the effect of Attention Condition on ssVEP power was not significant, F(1,11)=2.1, p=.177. The Attention Condition by Object (middle bar, peripheral bar, outside bar, unattended image), however, was significant, F(3,33)=13.4, p<.001, ε=0.868. The outside bars and unattended image were unaffected by the attention manipulation. Post-hoc contrasts indicated that this interaction resulted specifically from the differential response of the middle and peripheral bars to the attention manipulation, F(1,11)=20.9, p<.001 (see Figure 4). Going from the attend-all to the attend-mid condition, the middle bar increased in power, t(11)=4.1, p=.002, while the peripheral bar decreased in power, t(11)=−2.9, p=.015, in the 5-bar study.

Figure 4.

Mean power (plus standard error) of the ssVEP for all three studies.

Relationship between Behavior and Brain Activity

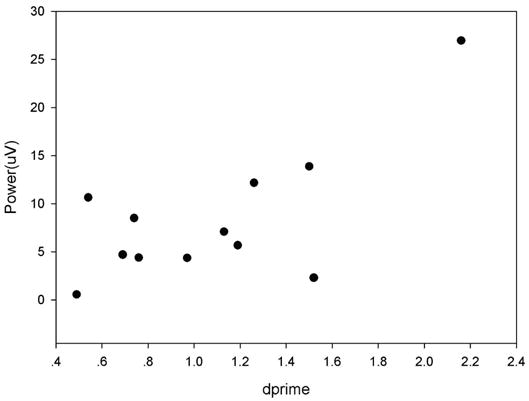

Pearson correlations were used to investigate the relationship between behavioral responses and selective attention within each experiment. Selective attention (ssVEP power) and behavioral response (d-prime and correct response reaction times) difference scores were computed for these variables (attend-mid minus attend-all conditions) for each study; these differences scores were used as the dependent variables in the correlation analyses. The only correlation that was statistically significant was between the difference in ssVEP power to the middle bar and difference in d-prime for the 5-bar study, r(12)=0.70, p=0.011 (see Figure 5), indicating that a greater increase in ssVEP power across conditions was associated with better detection ability.

Figure 5.

Bivariate scatter plot of change in middle bar d-prime values (narrow minus the broad attention conditions) as a function of the change in middle bar ssVEP power (narrow minus the broad attention conditions) in the 5-bar study.

Discussion

The present experiments investigated the neural correlates of selective attention when attended and unattended images spatially overlapped. Some results (the 5-bar study) were consistent with the thesis that attention can enhance neural activity to specific target events, even in a cluttered visual environment (Valdes-Sosa et al., 1998). These effects were not universal, as evidenced in the 3-bar study where both the unattended stimuli and attended target received neuronal enhancement. This result may highlight the limits of large scale neural enhancement as a target identification mechanism. As has been hypothesized for the case of color discrimination (e.g. Müller & Keil, 2004), the amplitude of neural mass activity may be insensitive to other processes such as neural synchronization, which appear essential for attentive stimulus processing. Future work may employ the time-frequency aspects of macroscopic brain oscillations to elucidate the contribution of these processes for resolving superimposed stimuli.

The results of the 7-bar experiment were inconsistent with those of Chen et al. (2003), who reported paradoxically lower signal strength to the attended compared to the unattended image, when only the center part of the display required attention. By contrast, they observed neural enhancement when width changes across the entire array were task-relevant. In our study, there were no differences between the ssVEP power for attended and unattended bars in both the broad and the narrow conditions.

The most obvious difference between Chen et al. (2003) and the present research is method of brain activity measurement. Magneto-encephalography (MEG), as used in the Chen et al. (2003) study is primarily sensitive to activity of cortical pyramidal cells tangentially oriented to the recording sensors. In addition, MEG does not have some of the complications associated with recording voltage differences in a volume conductor as is the case with EEG. Thus, MEG may be more sensitive than EEG to focal activity and to changes in smaller cell populations. Given the increased sensitivity to activity in sulci (MEG) versus gyri (EEG), differences in results between studies may be expected to be complementary rather than converging in every respect.

The outcome of our 5-bar experiment, however, suggests an additional explanation for the difference in the 7-bar results between Chen et al. (2003) and the present report. In the 5-bar experiment, the ssVEP to the middle bar was strongly modulated by selective attention, being significantly increased in the attend-mid versus attend-all condition. In addition, the ssVEP to the peripheral bars decreased from the attend-all (when they were relevant for target identification) to the attend-mid condition (when they were no longer relevant). This pattern explains why in the 7-bar experiment, in which ssVEP responses to middle and peripheral bars were not differentiable, the attended image did not show a broad versus narrow attention effect. With the ssVEP response to some parts of the whole image increasing (middle bar) and to other parts of the image decreasing (peripheral bars), the overall effect would be an apparent lack of attentional modulation. This finding is more consistent with Kanwisher & Wojciuliks’ (2000) thesis of differential enhancement of attention-related neural activity than with the operation of an inhibitory attentional mechanism (see also Valdes-Sosa et al., 1998). The results of the 7-bar and 5-bar studies also indicate that the level of analysis should be commensurate with the specificity of the selective attention effect to properly quantify its influence.

The findings of the 5-bar experiment showed that selective attention can be relatively specific for spatially distinct parts of an attended image at 1-2 deg of separation (Müller & Hübner, 2002; Müller et al., 2003). There was inconsistency across experiments, however, concerning the specificity of attention to an attended object that spatially overlapped an unattended image. In both the 7- and 5-bar experiments, ssVEP power for the unattended image was not modulated by attention condition. But in the 3-bar experiment, the ssVEP increased in the attend-mid condition to both the middle and peripheral bars of the attended image and the spatially overlapping unattended image.

There are at least two explanations for this result. First, perhaps the ssVEP to at least parts of the unattended image in the 7- and 5-bar experiments was increased during the attend-mid condition, but our level of measurement was too coarse to detect the change (in the same manner that modulation of the target bars of the attended image was undetectable in the 7-bar experiment). If so, this would indicate that (i) selective attention in the present design uses a location-, not a feature- or object-based mechanism and (ii) because selective attention cannot specifically enhance neural activity to objects as simple as edges, such enhancements may start as early as location-specific neurons in LGN (O’Connor, Fukui, Pinsk, & Kastner, 2002) and may be incapable of being refined via top-down control at later visual processing stages. This thesis seems inconsistent with other data (Luck & Hillyard, 2000; Müller & Hübner, 2002; Valdes-Sosa et al., 1998), although we cannot rule it out given the present experiments. Second, in the 3-bar experiment observers may have had a more difficult time parsing the overlapping stimuli into attended and unattended images. The additional bar lengths in the 5-bar experiment (4 deg longer than in the 3-bar experiment) may have enhanced perceptual separation of the middle and peripheral bars in the attended image from the unattended image. Attention may have spread to the unattended parts of the stimuli in the 3-bar experiment in a similar fashion as occurs when “foreground” and “background” must be modally rather than amodally completed (Driver, Davis, Russell, Turatto, & Freeman, 2001; Scholl, 2001); see also Meese & Freeman, 1995). These results may indicate that, although selective attention-related neural enhancements may begin in LGN, they are capable of being refined at later processing stages if the perceptual demands are amenable (e.g., Müller & Hübner, 2002).

A limitation of the present procedure is that the observed effects cannot be easily attributed to either feature- or object-based selection specifically. This distinction was not the main focus of the present study, but future ssVEP studies may usefully include stimulus arrays and experimental designs that control for the possibility that participants form visual objects rather than relying on single features. For instance, Nobre, Rao and Chelazzi (2006) used a negative priming design together with grating stimuli comprising motion and/or color features within one object. Their results suggested that even when differential object cues are absent, selectively attending to single features such as color or motion is associated with specific neural modulation, suggesting active inhibition of irrelevant features. Similar processes may have contributed to the present results leading to parallel modulations that enhanced neural activity to the attended stimulus and ignoring of features that were irrelevant in the given context. When using simultaneously displayed and overlapping stimuli these two processes may act in parallel and be discernable in differentially frequency-tagged ssVEP streams. Under certain conditions, the result could be an enhancement for both attended and unattended stimuli (see the results of our 3-bar experiment). A report by Ding and colleagues (2006) suggests that such seemingly paradoxical effects may depend on the tagging frequency used. Experimental designs such as that of Nobre et al. (2006) will be required to test predictions concerning when such types of broad versus narrow amplification are observed.

Selective attention theoretically supports the ability to bias neural signals in favor of stimulus locations and/or features (Pessoa, Kastner, & Ungerleider, 2003), although a firm relationship between neural enhancements and processing of relevant stimuli is yet to be established (Driver & Frackowiak, 2001). In the present report, there was a relationship between neural enhancement associated with a narrower focus of attention and better target detection (see Figure 5). Selective attention may assist with perception of relevant stimuli, but the ability of this mechanism to enhance specific neural firing associated with target selection and identification in complex visual scenes may be limited in certain visual environments (see the results of the 3-bar study). The partial success of selective attention in a complex visual world would be obviously helpful for speeding identification of relevant stimuli, but its limits may hint at the perceptual underpinning of, for instance, concealment mechanisms in nature. If predator or prey can confuse the perceptual system of other animals (by blending with the background enough to limit selective attention’s ability to make the separation), the additional time it takes for selective attention to verify the presence of danger or food may be the advantage needed to increase the chances for survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank Abby Stevens for help running the experiments. This work was supported by grants from the United States Public Health Service (MH51129 and MH57886). Correspondence concerning this article to: Brett A. Clementz, Ph.D., Psychology Department, Psychology Building, University of Georgia, Athens GA 30602; phone: 706-542-4376; FAX: 706-542-3275; email: clementz@uga.edu

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chen Y, Seth AK, Gally JA, Edelman GM. The power of human brain magnetoencephalographic signals can be modulated up or down by changes in an attentive visual task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337630100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Sperling G, Srinivasan R. Attentional modulation of SSVEP power depends on the network tagged by the flicker frequency. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16(7):1016–1029. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Russo F, Pitzalis S, Aprile T, Spitoni G, Patria F, Stella A, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of the cortical sources of the steady-state visual evoked potential. Human Brain Mapping. 2006 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20276. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Davis G, Russell C, Turatto M, Freeman E. Segmentation, attention and phenomenal visual objects. Cognition. 2001;80:61–95. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Frackowiak RSJ. Neurobiological measures of human selective attention. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillyard SA, Anllo-Vento L. Event-related brain potentials in the study of visual selective attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:781–787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, Wojciulik E. Visual attention:insights from brain imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2000;1:91–100. doi: 10.1038/35039043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Pinsk MA. Visual attention as a multilevel selection process. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;4:483–500. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Gruber T, Muller MM, Moratti S, Stolarova M, Bradley MM, et al. Early modulation of visual perception by emotional arousal: evidence from steady-state visual evoked brain potentials. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2003;3(3):195–206. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Moratti S, Sabatinelli D, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Additive effects of emotional content and spatial selective attention on electrocortical facilitation. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15(8):1187–1197. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Hillyard SA. The operation of selective attention at multiple stages of processing:evidence from human and monkey electrophysiology. In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. The New Cognitive Neurosciences. 2. The MIT Press; Cambridge: 2000. pp. 687–700. [Google Scholar]

- Mast J, Victor JD. Fluctuations of steady-state VEPs: interaction of driven evoked potentials and the EEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;78(5):389–401. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(91)90100-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meese TS, Freeman TCA. Edge computation in human vision: anisotropy in the combining of oriented filters. Perception. 1995;24:603–622. doi: 10.1068/p240603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratti S, Keil A. Cortical activation during Pavlovian fear conditioning depends on heart rate response patterns: an MEG study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;25(2):459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratti S, Keil A, Miller GA. Fear but not awareness predicts enhanced sensory processing in fear conditioning. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(2):216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-8986.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratti S, Keil A, Stolarova M. Motivated attention in emotional picture processing is reflected by activity modulation in cortical attention networks. Neuroimage. 2004;21(3):954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ST, Hansen JC, Hillyard SA. Selective attention to stimulus location modulates the steady-state visual evoked potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4770–4774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MM, Hillyard SA. Concurrent recording of steady-state and transient event-related potentials as indices of visual-spatial selective attention. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(9):1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MM, Hübner R. Can the spotlight of attention be shaped like a doughnut? Evidence from steady-state visual evoked potentials. Psychological Science. 2002;13:119–124. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MM, Keil A. Neuronal synchronization and selective color processing in the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16(3):503–522. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MM, Malinowski P, Gruber T, Hillyard SA. Sustained division of the attentional spotlight. Nature. 2003;424:309–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MM, Teder-Salejarvi W, Hillyard SA. The time course of cortical facilitation during cued shifts of spatial attention. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(7):631–634. doi: 10.1038/2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Rao A, Chelazzi L. Selective attention to specific features within objects: behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18(4):539–561. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DH, Fukui MM, Pinsk MA, Kastner S. Attention modulates responses in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(11):1203–1209. doi: 10.1038/nn957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor MA, Artieda J, Arbizu J, Valencia M, Masdeu JC. Human Cerebral Activation during Steady-State Visual-Evoked Responses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(37):11621–11627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11621.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei F, Pettet MW, Norcia AM. Neural correlates of object-based attention. Journal of Vision. 2002;2(9):588–596. doi: 10.1167/2.9.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Neuroimaging studies of attention: from modulation of sensory processing to top-down control. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:3990–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03990.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton TW, Vajsar J, Rodriguez R, Campbell KB. Reliability estimates for steady-state evoked potentials. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1987;68(2):119–131. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(87)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plourde G, Picton TW. Human auditory steady-state response during general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1990;71(5):460–468. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan D. Human brain electrophysiology: evoked potentials and evoked magnetic fields in science and medicine. New York: Elsevier Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Regan MP, Regan D. Techniques for investigating and exploiting nonlinearities in brain processes by recording responses evoked by sensory stimuli. In: Lu Z, Kaufman L, editors. Magnetic source imaging of the human brain. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez V, Valdes-Sosa M, Freiwald W. Dividing attention between form and motion during transparent surface perception. Cognitive Brain Research. 2002;13:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(01)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl BJ. Objects and attention: the state of the art. Cognition. 2001;80:1–46. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein RB, Schier MA, Pipingas A, Ciorciari J, Wood SR, Simpson DG. Steady-state visually evoked potential topography associated with a visual vigilance task. Brain Topogr. 1990;3(2):337–347. doi: 10.1007/BF01135443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes-Sosa M, Bobes MA, Rodriguez V, Pinilla T. Switching Attention without Shifting the Spotlight: Object-Based Attentional Modulation of Brain Potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10(1):137–151. doi: 10.1162/089892998563743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]