Abstract

Biglycan (Bgn) and decorin (Dcn) are highly expressed in numerous tissues in the craniofacial complex. However, their expression and function in the cranial sutures is unknown. In order to study this, we first examined the expression of biglycan and decorin in the posterior frontal suture (PFS), which predictably fuses between 21–45 days post-natal and in the non-fusing sagittal (S) suture from wildtype (Wt) mice. Our data showed that Bgn and Dcn were expressed in both cranial sutures. We then characterized the cranial suture phenotype in Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient, Bgn/Dcn double deficient, and Wt mice. At embryonic day 18.5, alizarin red/ alcian blue staining showed that the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice had hypomineralization of the frontal and parietal craniofacial bones. Histological analysis of adult mice (45–60 days post natal) showed that the Bgn or Dcn deficient mice had no cranial suture abnormalities and immunohistochemistry staining showed increased production of Dcn in the PFS from Bgn deficient mice. To test possible compensation of Dcn in the Bgn deficient sutures we examined the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice and found they had impaired fusion of the PFS. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA from 35 day-old mice revealed increased expression of Bmp-4 and Dlx-5 in the PFS compared to their non-fusing S suture in Wt tissues and decreased expression of Dlx-5 in both PF and S sutures in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice compared to the Wt mice. Failure of PFS fusion and hypomineralization of the calvaria in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice demonstrate these extracellular matrix proteoglycans could have a role in controlling the formation and growth of the cranial vault.

Keywords: Small Proteoglycans, biglycan, decorin, cranial suture and mouse

Introduction

Biglycan (Bgn) and decorin (Dcn) are members of the small leucine repeat proteoglycan family (SLRP). Members of this family are characterized by a small protein core, which consists predominantly of leucine-rich repeats. There are 13 known members of this family that are divided into three classes depending on their genomic organization and the similarity of their amino acid sequences. Bgn and Dcn belong to the class I type SLRP and are highly expressed in skeletal and connective tissues (1, 12, 14, 15, 31). The exact function of both Bgn and Dcn are unknown, however both can bind and modulate members of the TGF-beta superfamily (11).

Bgn deficient mice have impaired postnatal bone formation which may be due to the ability of Bgn to modulate the actions of Bone morphogenic proteins-2/4 (Bmp-2/4) in osteoblastic cells, potentially contributing to the failure to achieve peak bone mass and early onset of osteoporosis (4, 36). Dcn deficient mice do not have obvious skeletal defects, but instead, have skin fragility which is hypothesized to be due to the ability of Dcn to modulate collagen fibril structure and integrity (7). Because of their similarity in structure and their overlapping expression in skeletal and connective tissues, it is probable that Bgn and Dcn function redundantly. Support of this concept comes from the analysis of Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice that have a more severe phenotype in both long bone and skin (2, 5) compared to Wt or singly deficient SLRP mice.

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of Bgn and Dcn in the craniofacial complex. In the craniofacial region, Bgn and Dcn are present in teeth (22, 28), periodontal tissues (21), nasal cartilage (29), eye (8), temporomandibular joint (18), the developing mandible (16, 35) and the developing calvaria (35). Despite their prevalence in numerous tissues of the craniofacial complex, little is known about their function in these tissues. In order to examine this further and to eliminate potential compensation of Dcn with Bgn, we examined whether a craniofacial phenotype could be unmasked by creating Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice and comparing them to the single Bgn deficient, single Dcn deficient and control Wt mice.

There is similarity and conservation in the molecular pathways that control the assembly and growth of the cranial vault between humans and mice (33). In mice all the cranial vault sutures remain open throughout the lifespan of the animal, except for the posterior frontal suture (PFS), which fuses in a predictable fashion between 21–45 days postnatal (25). In humans the equivalent metopic suture fuses within the first three years postnatal (30, 34). Therefore, the mouse PFS serves as a model of post-natal human sutural growth (33). Bmp-2/4 signaling has been linked to murine PFS fusion by Warren et al., who showed that inhibition of the Bmp-2/4 signaling pathway by adenovirus mis-expression of the Bmp antagonist Noggin blocks murine PFS fusion in vivo (32). Since both biglycan and decorin can modulate Bmp-2/4 signaling, we hypothesized that in their absence, there would be defective Bmp-2/4 signaling and impaired PF sutural fusion.

In this study, we found that Bgn and Dcn were expressed in the fusing PFS and in the non-fusing S suture in Wt mice. The PFS in both Dcn deficient and Bgn deficient mice revealed no defects. However, further examination of the PFS in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice showed a lack of PFS fusion in a mechanism that is potentially related to decreased expression of Dlx-5.

Experimental Procedures

Generation of Bgn and Dcn Single and Double Deficient Mice

All experiments were performed under an institutionally approved protocol for the use of animals in research (#NIDCR-IRP-98–058 and 01–151). Mice deficient in Bgn and Dcn were generated by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells as described previously (7, 36). Heterozygous Bgn/Dcn deficient mice were produced by breeding a homozygous Bgn deficient female (Bgn−/−/ Dcn +/+) with an Dcn heterozygous deficient male (Bgn+/0 / Dcn+/−); Bgn−/ − deficient males are designed as Bgn −/0 since the Bgn gene is located on the X chromosome and absent from the Y chromosome. F2 Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice were obtained by interbreeding F1 heterozygous Bgn/Dcn deficient animals. In order to maximize the number of double deficient mice obtained the following breeding scheme was used: Bgn 0/− / Dcn+/− males were bred to Bgn +/−/ Dcn+/− females. The cranial vault of the mice was analyzed at embryonic day 18.5, and post-natal days 35, 42 and 60. We chose to examine 42 days and 60 days post-natal (the posterior frontal suture normally fuses between 21–45 days postnatal) because they represent time points during and well past normal PFS closure which allowed us to evaluate if there was a delay or failure of PFS fusion in the transgenic mice. We selected post-natal day 35 for our RT-PCR analysis because we wanted to evaluate whether there would be differences in gene expression during the time of normal posterior frontal sutural fusion.

Genotyping

All mice were genotyped for Bgn and Dcn alleles by PCR analysis as described (5). PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis through 1.8% agarose gels, yielding bands of 212 bp for the Wt Bgn allele, 310 bp for the disrupted Bgn allele, 161 bp for the Wt Dcn allele, and 238 bp for the disrupted Dcn allele.

Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue Staining of Mice Littermates

In our experimental approach, we used a breeding scheme that would maximize the number of Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice, and for this reason, we were unable to obtain a homozygous Wt mouse and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mouse in the same litter. Therefore, in this first part of the study we used (Bgn +/−/ Dcn+/+) mice as our controls. 18.5 d.p.c. littermates obtained from 5 litters were euthanized, and then their skin, muscle, and fat were removed. The animals were fixed in 100 % ethanol for 4 days and then placed in acetone for 3 days. Mice were then stained with alizarin red (0.09%) and alcian blue (0.05%) in a solution containing ethanol, glacial acetic acid, and water (67:5:28) for 3 days. After staining, mouse samples were transferred to 1% KOH until their soft tissues were dissolved and then preserved in a 100% glycerol (23).

Faxitron

Sixty day-old mice were divided into four groups, Wt, Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient and Bgn/Dcn double deficient, with an n=3 for each group. The mice were sacrificed and the soft tissues on their heads were removed. The calvaria were radiographed using a Faxitron MX-20 Specimen Radiography System (Faxitron X-ray Corp., Wheeling, IL, USA) at energy of 90 kV for 20 s. The images were captured with Eastman Kodak Co. X-OMAT TL (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY, USA).

In order to determine the optimal length of a rectangular box that could be used to quantitate the amount of radio-opacity in the PFS, the length of the PFS from 60 day-old Wt, Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice was first measured. The mean length +/− the standard error of the PFS was 11.0 +/− .6 mm for Wt, 10.3 +/− 0.3 mm from Bgn deficient, 10.7 +/− 1.2 mm from Dcn deficient and 11.7 +/− 0.3 mm for Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice. Evaluation of differences among the means by analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were no significant differences in the length of the PFS between the groups. Therefore, a 10 mm by 3 mm rectangular box was used to measure the amount of radio-opacity in the PFS from the different groups. The amount of radio-opacity in the PFS was quantitated by using Image J NIH IMAGE.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Wt, Dcn deficient, Bgn deficient, and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at 35–45 days after birth. Calvaria were removed and fixed for 2 weeks at room temperature in 10% formalin. After being washed in water for 5 minutes, they were decalcified in formic acid bone decalcifier solution (Immunocal from Decal Corporation, Tallman, NY, USA) for 4 weeks. Specimens were then washed in water for 5 minutes and fixed for 3 days in buffered zinc formalin (Z-fix from Anatech Ltd, Battle Creek, MI, USA) before being classically processed for histology and sectioned coronally. Sections were stained with H&E.

Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene. Following rehydration with decreasing concentrations of ethanol, the sections were treated with 3 % peroxide in methanol for 20 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. In order to expose the antigen, sections were predigested in chondroitinase ABC (cat# KE01502, Seikagaku Corp, Tokyo, Japan) at a concentration of 0.015 units/ml for 1 hour at 37 C. Incubating the sections in 10% goat serum for 30 minutes reduced non-specific binding. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4° C with primary antibody at a 1: 200 dilution. Dcn and Bgn antibodies (respectively LF 113 and LF 106) were kind gifts from Larry Fisher (NIDCR, NIH). Biotinylated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody was used and visualized by a streptavidin-peroxidase solution in the presence of DAB chromagen. The negative control consisted of the above mentioned procedures except for the substitution of the primary antibody with rabbit IgE.

The data presented in this paper were reproduced in at least 6 different sections from two separate animals for each group. Serial sections through the whole suture were obtained for each animal and observations were confirmed in different interspaced serial sections chosen to cover the whole suture. In this way, it was ensured that the reported observations were genuine and not local random abnormalities. In each case, data from a single representative experiment are shown.

Isolation of the Suture Complex for mRNA Extraction

Posterior frontal (PF) and sagittal (S) suture complexes (including the associated dura mater, suture mesenchyme, and osteogenic fronts) were harvested from 35 day-old male Wt (n=4) and Bgn/Dcn (n=2) double deficient mice. Mice were euthanized with carbon dioxide, and the posterior frontal and sagittal suture complexes were isolated under a dissecting microscope as previously described (24).

Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the cranial suture material using Trizol-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) following the manufacture’s instructions. One microgram total RNA from the sample preparation was reverse transcribed with 50 units of SuperScript II RT using random hexamer primers (InVitrogen Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used for amplification were designed with Primer 3 software (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgibin/primer/primer3.cgi). The primers used for RT-PCR were for Gapdh 5′gagaggccctatcccaact3′ (forward) 5′gtgggtgcagcgaactttat3′ (reverse), for Bmp-4 5′ ggtgggtttgcttccactta3′ (forward) and 5′atgggagcgagttgtgtacc3′ (reverse), for Dlx-5 5′ccgggacgctttattagatg3′ (forward) and 5′tggacactatcaatggtgcc3′ (reverse), for biglycan 5′acctgtccccttccatctct3′ (forward) and 5′ccgtgtgtgtgtgtgtgtgt3′ (reverse), for decorin 5′ccaacataactgcgatccct3′ (forward) and 5′tgtccaagtggagttccctc3′ (reverse) and for 18s 5′catgtggtgtgaggaaa3′ (forward) and 5′gcccagagactcatttctt3′ (reverse). PCR was performed using a hot start (with Taq Gold™, Applied Biosystems) at 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles (biglycan, decorin, 18s, and GAPDH) or 50 cycles (Dlx-5 and Bmp-4) of 1 min at 94°C, 20 seconds at 57°C and 30 seconds at 72°C followed by a 7 minute extension at 70°C. The reaction was chilled to 4°C afterwards until it was analyzed. Sixteen microlitres of the PCR product and a 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL) were run in a 10% acrylamide gel (TBE) buffer at 100 V. The products separated by electrophoresis were visualized after ethidium bromide staining under a UV light and photographed in a single field of view with a digital camera. Individual bands on digital micrographs of RT-PCR products were analyzed by densitometer using Image J NIH IMAGE. Intensity for Dlx-5, Bgn, Dcn and Bmp-4 were calculated as a percentage of densitometry values for control bands of Gapdh or 18s. Each primer set was tested previously to assure that amplification was in the linear range by analyzing amplification at several different cycle numbers.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of differences among means was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparison of more than two means by the Bonferroni method using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, Ca).

Results

Alizarin Red-Alcian Blue Staining of E 18.5 Littermates

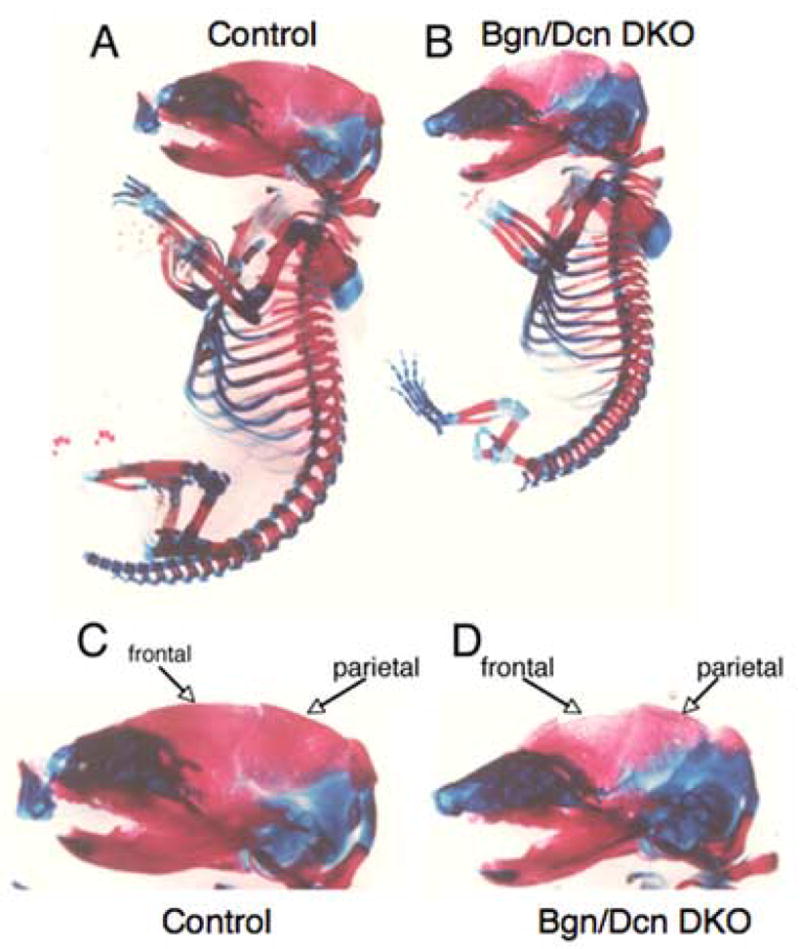

Alizarin red-alcian blue staining of E 18.5 control (Bgn +/−/ Dcn +/+ was used as the control due to the inability to generate a Wt and a Bgn/Dcn double deficient in the same litter) and Bgn/Dcn double deficient littermates revealed that the Bgn/Dcn double deficient embryos had severe hypomineralization of the frontal and parietal bones (Figure 1A–D). Alizarin red and alcian blue staining were also performed on two additional Bgn/Dcn double deficient embryos along with two littermate controls revealing similar results (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Alizarin red/alcian blue staining of E18.5 littermates. a, c. Control Bgn +/− Dcn +/+ mice. b, d. Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice.

Expression of Bgn and Dcn in the PFS and Sagittal Suture from Wt Mice

A time course for the expression of Bgn and Dcn was determined in the PF and the S suture in Wt mice at day 21, day 25 and day 35 post-natally by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The data indicated that mRNA encoding both biglycan and decorin is abundantly expressed in both the posterior frontal and sagittal suture during maturation (Figure 2a). Since there appeared to be increased expression of Bgn mRNA in the PF compared to the S suture during the late phases of PFS fusion, we repeated the experiments two more times at day 35 post-natal. In the three independent experiments from 35 day-old Wt mice, we found that the ratio of Bgn mRNA expression in the PFS / S suture was 1.1 +/− 0.3

Figure 2.

Expression of Bgn and Dcn in cranial sutures. A. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis performed for Dcn and Bgn on RNA extracted from the sagittal (S) suture and the posterior frontal suture (PFS) from 21, 25 and 35 day-old wildtype (Wt) mice. b-e . Immunohistochemistry (brown) for biglycan (B, D) and decorin (C, E) on coronal sections of the posterior frontal suture from 42 day-old Wt (B, C) and Bgn deficient mice (D, E). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (blue).

In order to determine the precise localization of Bgn and Dcn protein expression in the PFS and to evaluate possible compensation at the protein level, immunohistochemistry for Bgn and Dcn was performed in 42 day-old Wt and Bgn deficient mice (Figure 2B–E). In the PFS from the Wt and Bgn deficient mice, Dcn was found in the underlying dura (Figure 2C, E). In the Wt mice, Dcn appeared to have a more restricted expression pattern in the dura compared to Bgn deficient mice where it was found at a higher level and throughout the structure. In contrast, the PFS from the Dcn deficient mice had no change in the localization of Bgn in the underlying dura compared to Wt mice (data not shown). Negative controls consisting of the substitution of the primary antibody with rabbit IgE revealed no visible staining (data not shown).

Analysis of the PFS from Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient, Bgn/Dcn Double Deficient and Wt Mice

In order to determine what role Bgn and Dcn deficiency had on later developmental stages, 60 day-old Wt and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice were examined. Faxitron analysis showed that the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice had a clear absence of radio-opacity in the PFS. On the other hand, calvaria obtained from 60 day-old Wt, Bgn deficient and Dcn deficient mice, all had PFS that were radio-opaque (data not shown). Quantification of the amount of radio-opacity in the PFS by X-ray scanning and NIH-image analysis revealed that it was significantly decreased in Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice compared to the other groups (p < 0.001) (Figure 3a). Besides a decrease in mineralization of the PFS, the decrease in radio-opacity in the PFS from the Bgn/Dcn double deficient could also be due to a difference in the structure and curvature of the calvaria. To test this possibility, coronal histological sections of the PFS from 45 day-old Bgn deficient (Figure 3C), Dcn deficient (Figure 3D), Bgn/Dcn double deficient (Figure 3E) and Wt mice (Figure 3B) were examined. This analysis revealed PFS patency only in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient samples compared to the other groups.

Figure 3.

Analysis of radio-opacity and histology of the PFS from Wt, Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient, and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice. a. Quantification of intensity of radio-opacity in the PFS from faxitron images of the calvaria from 60 day-old Wt, Bgn deficient, Dcn deficient, and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice. Each point is the mean and SEM for n=3 for each group. * Significant decrease in the intensity of radio-opacity in the PFS from the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice compared to the other groups, p > 0.001. b-e. H & E staining of coronal sections of the posterior frontal suture from 45 day-old Wt (b), Bgn deficient (c), Dcn deficient (d), and Bgn/Dcn double deficient (e) mice.

Expression of Bmp-4 and Dlx-5 mRNA in PFS and Sagittal Suture from 35 day-old Wt and Bgn/Dcn Double Deficient Mice

Because Bmp-2/4 signaling has been previously implicated in controlling PFS fusion (32), we examined the relative expression levels of Bmp-4 mRNA, and the Bmp-4 target gene, Dlx-5 mRNA (10) in our mouse model. Messenger RNA was extracted from the fusing PFS and non-fusing S sutures of 35 day-old Wt and in Bgn/Dcn double deficient and analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. These analyses showed that, Bmp-4 mRNA levels were higher in the (fusing) PFS compared to S suture in both genotypes. Interestingly, when Dlx-5 was measured in the same samples it was significantly higher in the Wt PFS compared to the S suture but absent in both S and PF sutures in Bgn/Dcn deficient mice (Figure 4). Similar results were obtained in a second independently repeated experiment (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR performed for Bmp-4 and Dlx-5 on RNA extracted from the sagittal (S) suture and the posterior frontal suture (PFS) from 35 day-old wildtype (Wt) and Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice. RT-PCR of Gapdh served as a normalizing control.

Discussion

This report shows that both biglycan (Bgn) and decorin (Dcn) are abundantly expressed in the cranial sutures of mice, with overlapping yet distinct patterns of expression in the fusing suture and the dura mater. We found that Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice have open sutures and severe hypomineralization of both frontal and parietal bones as early as E 18.5, while mice singly deficient in Bgn or Dcn have no suture formation defects.

Murine PFS fusion is controlled by a complex interaction between many different types of cells, tissue types and growth factors. For example, Warren et al. (32) has proposed that Fgf-2 secreted by the underlying dura causes a downregulation of Noggin within the posterior frontal sutural cells that allows Bmp- 2/ 4 to interact with the bone fronts to cause fusion of the PFS. For such orchestration of events to occur, there must be control of the localization and activity of the secreted growth factors. Proteoglycans that could modulate the activity of growth factors within the extracellular matrix of the posterior frontal suture may provide this control (26).

Several lines of evidence link both Bgn and Dcn to Bmp-2/4 activity. In a recent study, we found that Bgn deficient calvarial osteoblast-like cells had less cell surface Bmp-4 binding, which led to reduced Bmp-4 mediated osteoblast differentiation in Bgn deficient calvarial osteoblast-like cells compared to Wt controls (4). Similar results have been noted in MC3T3-E1 cell-derived clones expressing higher or lower levels of biglycan (27). Dcn has been shown to modulate the actions of Bmp-2/4. Specifically Bmp-2 induction of alkaline phosphatase was diminished in Dcn deficient myoblast cells compared to Wt controls (9).

Bgn and Dcn are similar in structure and function and it is possible that they function redundantly. Immunohistochemistry revealed that in the absence of Bgn, Dcn is up regulated throughout the PFS. Dcn expression was restricted to the inferior portion of the dura in Wt mice but more evenly distributed throughout the underlying dura of the PFS in Bgn deficient mice. We have also previously reported increased expression of Dcn in Bgn deficient osteoblastic cell cultures (4). Furthermore we found the ability of Bmp-2 to induce mineralization, as measured by alizarin red accumulation, was decreased 59% in osteoblast-like cells from Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice (2) compared to 30 % in Bgn only deficient osteoblast-like cells(4).

We hypothesize that the impaired PFS in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice is due to altered Bmp-4 signaling since we found equivalent mRNA expression of Bmp-4 but marked reduction of Dlx-5 expression in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient cranial sutures. Many extracellular and intracellular proteins, such as Dlx-5, regulate the Bmp- 2/ 4 signaling pathway. Specifically, Bmp-2/4 has been shown to increase Dlx-5 expression in avian calvarial explant cultures (13) and in osteoblastic cell cultures (10). In addition, the BMP2/ 4 regulation of the osteoblast differentiation markers, Runx-2, Osterix, and Alkaline phosphatase, appears to be dependent on Dlx-5 (17, 19, 20). Impaired PFS fusion in the Bgn/Dcn double deficient mice may be due to failure of appropriate expression of signaling molecules involved in promoting bone formation and mineralization, which is consistent with previous findings of severe osteopenia (2, 5) and decreased expression of Dlx-5 in the cranial sutures. However, as has been suggested by others, it is important to consider the possibility that additional factors besides increased or decreased bone formation could control abnormal cranial suture fusion (3, 6).

In conclusion, we show that the alteration in the extracellular matrix of the posterior frontal suture causes impaired fusion. These new data provide the foundation for the identification of novel candidate genes for patients who have sutural growth disturbances.

Table 1. Summary of Craniofacial Anomalies in Bgn, Dcn and Bgn/Dcn Deficient Mice Compared to Wt.

Normal Wt mice and mice deficient in Bgn, Dcn or both (Genotype, column 1) were analyzed embryonic day 18.5 (E 18.5) by alizarin red/ alcian blue staining (column 2) or post-natally (60 days after birth) by Faxitron X-ray or histology (column 3). Specific mRNA or protein expression in the normal and mutant mice was examined in PF (Posterior Frontal) or Sagittal (S) sutures 35–45 days after birth (column 4).

| Genotype | E 18.5 Calvaria | Post-natal PF fusion | Suture Gene/protein expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wt | normal | normal | Dlx-5 and Bmp-4 mRNA higher in PF vs. S |

| Bgn Deficient | ND | normal | Dcn protein higher in Bgn Deficient |

| Dcn Deficient | ND | normal | Bgn protein unaffected |

| Bgn/Dcn Deficient | Hypomineralized | patent suture | Dlx-5 mRNA absent in PF and S sutures |

ND=not determined.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research in the Intramural Program of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ameye L, Young MF. Mice deficient in small leucine-rich proteoglycans: novel in vivo models for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, muscular dystrophy, and corneal diseases. Glycobiology. 2002;12:107R–16R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bi Y, Stuelten CH, Kilts T, Wadhwa S, Iozzo RV, Robey PG, Chen XD, Young MF. Extracellular matrix proteoglycans control the fate of bone marrow stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Li D, Li C, Engel A, Deng CX. A Ser250Trp substitution in mouse fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2) results in craniosynostosis. Bone. 2003;33:169–78. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen XD, Fisher LW, Robey PG, Young MF. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan biglycan modulates BMP-4-induced osteoblast differentiation. Faseb J. 2004;18:948–58. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0899com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corsi A, Xu T, Chen XD, Boyde A, Liang J, Mankani M, Sommer B, Iozzo RV, Eichstetter I, Robey PG, Bianco P, Young MF. Phenotypic effects of biglycan deficiency are linked to collagen fibril abnormalities, are synergized by decorin deficiency, and mimic Ehlers-Danlos-like changes in bone and other connective tissues. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1180–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabovic B, Chen Y, Colarossi C, Zambuto L, Obata H, Rifkin DB. Bone defects in latent TGF-beta binding protein (Ltbp)-3 null mice; a role for Ltbp in TGF-beta presentation. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:129–41. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funderburgh JL, Hevelone ND, Roth MR, Funderburgh ML, Rodrigues MR, Nirankari VS, Conrad GW. Decorin and biglycan of normal and pathologic human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1957–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez J, Osses N, Brandan E. Changes in secreted and cell associated proteoglycan synthesis during conversion of myoblasts to osteoblasts in response to bone morphogenetic protein-2: Role of decorin in cell response to BMP-2. J Cell Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/jcp.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris SE, Guo D, Harris MA, Krishnaswamy A, Lichtler A. Transcriptional regulation of BMP-2 activated genes in osteoblasts using gene expression microarray analysis: role of Dlx2 and Dlx5 transcription factors. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1249–65. doi: 10.2741/1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen LM, Heinegard D, Twardzik DR, Border WA, Ruoslahti E. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor beta. Biochem J. 1994;302 (Pt 2):527 –34. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holleville N, Quilhac A, Bontoux M, Monsoro-Burq AH. BMP signals regulate Dlx5 during early avian skull development. Dev Biol. 2003;257:177–89. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iozzo RV. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18843–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141–74. doi: 10.3109/10409239709108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamiya N, Shigemasa K, Takagi M. Gene expression and immunohistochemical localization of decorin and biglycan in association with early bone formation in the developing mandible. J Oral Sci. 2001;43:179–88. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.43.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YJ, Lee MH, Wozney JM, Cho JY, Ryoo HM. Bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced alkaline phosphatase expression is stimulated by Dlx5 and repressed by Msx2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50773–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwabara M, Takuma T, Scott PG, Dodd CM, Mizoguchi I. Biochemical and immunohistochemical studies of the protein expression and localization of decorin and biglycan in the temporomandibular joint disc of growing rats. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47:473–80. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee MH, Kim YJ, Kim HJ, Park HD, Kang AR, Kyung HM, Sung JH, Wozney JM, Kim HJ, Ryoo HM. BMP-2-induced Runx2 expression is mediated by Dlx5, and TGF-beta 1 opposes the BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation by suppression of Dlx5 expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34387–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MH, Kwon TG, Park HS, Wozney JM, Ryoo HM. BMP-2-induced Osterix expression is mediated by Dlx5 but is independent of Runx2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:689–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matheson S, Larjava H, Hakkinen L. Distinctive localization and function for lumican, fibromodulin and decorin to regulate collagen fibril organization in periodontal tissues. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:312–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuura T, Duarte WR, Cheng H, Uzawa K, Yamauchi M. Differential expression of decorin and biglycan genes during mouse tooth development. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:367–73. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miura M, Chen XD, Allen MR, Bi Y, Gronthos S, Seo BM, Lakhani S, Flavell RA, Feng XH, Robey PG, Young M, Shi S. A crucial role of caspase-3 in osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1704–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI20427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nacamuli RP, Song HM, Fang TD, Fong KD, Mathy JA, Shi YY, Salim A, Longaker MT. Quantitative transcriptional analysis of fusing and nonfusing cranial suture complexes in mice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1818–25. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000143578.41666.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opperman LA. Cranial sutures as intramembranous bone growth sites. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:472–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1073>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opperman LA, Rawlins JT. The extracellular matrix environment in suture morphogenesis and growth. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:127–35. doi: 10.1159/000091374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parisuthiman D, Mochida Y, Duarte WR, Yamauchi M. Biglycan modulates osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1878–86. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenorio DM, Santos MF, Zorn TM. Distribution of biglycan and decorin in rat dental tissue. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:1061–5. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK, Papageorgakopoulou N, Tsiganos CP, Theocharis DA. Isolation and characterization of matrix proteoglycans from human nasal cartilage. Compositional and structural comparison between normal and scoliotic tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1569:117–26. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu HL, Panchal J, Parker EE, Levine NS, Francel P. The timing of physiologic closure of the metopic suture: a review of 159 patients using reconstructed 3D CT scans of the craniofacial region. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12:527–32. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadhwa S, Embree MC, Bi Y, Young MF. Regulation, regulatory activities, and function of biglycan. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2004;14:301–15. doi: 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.v14.i4.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren SM, Brunet LJ, Harland RM, Economides AN, Longaker MT. The BMP antagonist noggin regulates cranial suture fusion. Nature. 2003;422:625–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren SM, Greenwald JA, Spector JA, Bouletreau P, Mehrara BJ, Longaker MT. New developments in cranial suture research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:523–40. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200102000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinzweig J, Kirschner RE, Farley A, Reiss P, Hunter J, Whitaker LA, Bartlett SP. Metopic synostosis: Defining the temporal sequence of normal suture fusion and differentiating it from synostosis on the basis of computed tomography images. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1211–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000080729.28749.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilda M, Bachner D, Just W, Geerkens C, Kraus P, Vogel W, Hameister H. A comparison of the expression pattern of five genes of the family of small leucine-rich proteoglycans during mouse development. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2187–96. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.11.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu T, Bianco P, Fisher LW, Longenecker G, Smith E, Goldstein S, Bonadio J, Boskey A, Heegaard AM, Sommer B, Satomura K, Dominguez P, Zhao C, Kulkarni AB, Robey PG, Young MF. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;20:78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]