Abstract

Since endocannabinoids modulate reward processing and the stress response, we tested the hypothesis that endocannabinoids regulate stress-induced decreased sensitivity to natural reward. Restraint was used to produce stress-induced reductions in sucrose consumption and preference in male mice. Central cannabinoid receptor (CB1) signaling was modulated pharmacologically prior to the application of stress. The preference for sucrose over water was significantly decreased in mice exposed to restraint. Treatment of mice with a cannabinoid receptor agonist (CP55940) or fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor (URB597) attenuated, while the CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, rimonabant (SR141716), enhanced, stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference. These data are consistent with a tonically active, stress-inhibitory role for the CB1 receptor. Mice treated with 10 daily episodes of restraint showed reduced sucrose preference that was unaffected by CP55940 and URB597. However, rimonabant produced a greater reduction in sucrose preference on day 10 compared to day 1. These data suggest that on day 10, endocannabinoid signaling is maximally activated and essential for reward sensitivity. The findings of the present study indicate that the CB1/endocannabinoid signaling system is an important allostatic mediator that both modulates the responses of mice to stress and is itself modulated by stress.

Keywords: allostasis, CB1 receptor, cannabinoid, fatty acid amide hydrolase, CP55940, rimonabant, URB597

1. Introduction

Several endocannabinoids have been identified, including N-arachidonylethanolamine (AEA) and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) that activate the central cannabinoid receptor (CB1) (Devane et al., 1992; Mechoulam et al., 1995; Sugiura et al., 1995). Endocannabinoids serve as activity-dependent, retrograde inhibitors of neurotransmitter release (Alger, 2002; Brown et al., 2003; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001) and are involved in the mechanisms that underlie synaptic plasticity, including depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition and excitation (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2001;Wilson et al., 2001).

The literature is mixed regarding the role that endocannabinoids play in the processing of reward. Although several groups have reported that cannabinoids produce a robust conditioned place preference (Braida et al., 2001a; Lepore et al., 1995; Valjent and Maldonado, 2000) others have reported that cannabinoids produce a conditioned place aversion (Parker and Gilles, 1995; McGregor et al., 1996; Sañudo-Pena et al., 1997). Although it has been reported that both the cannabinoid receptor agonists, WIN 55212-2 and CP55940, are self-administered by mice, an effect that is blocked by pretreatment with a CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (Braida et al., 2001b; Ledent et al., 1999; Martellotta et al., 1998), there are several instances in which a failure of cannabinoid self-administration has been reported (Mansbach et al., 1994; Takahashi and Singer, 1981) . Cannabinoid receptor agonists, at low and pharmacologically meaningful doses, enhance electrical brain stimulation reward (Gardner et al., 1988). CB1 receptor activation increases extracellular dopamine overflow in terminal regions of the reward circuit, an effect reversed by CB1 receptor blockade (Cheer et al., 2004; Tanda et al., 1997). In addition, genetic deletion of the CB1 receptor results in a reduction in the sensitivity to the rewarding effects of sucrose (Sanchis-Segura et al., 2004). CB1 receptor activation accentuates whereas CB1 receptor blockade attenuates the rewarding effects of sweet and palatable foods (Ward and Dykstra, 2005).

The effects of CB1 receptor activity in the regulation of stress are complex (Carrier et al., 2005). However, evidence is accumulating that tonic activation of CB1 receptors exerts a stress-inhibitory effect. For example, blockade of endogenous CB1 receptor activity with rimonabant increases adrenocorticotropin hormone and corticosterone plasma concentrations (Manzanares et al., 1999). Similarly, basal adrenocorticotropin hormone concentrations are increased in CB1 receptor null mice (Haller et al., 2004). On the other hand, inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) activity during stress inhibits activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Patel et al., 2004). FAAH catalyzes the hydrolysis of AEA (Deutsch and Chin, 1993) and 2-AG (Goparaju et al., 1998) in vitro. However, AEA but not 2-AG concentrations in brain are elevated in FAAH null mice (Lichtman et al., 2002; Patel et al. 2005a). Moreover, CB1 receptor activation decreases stress-related behaviors. For example, CB1 receptor activation by endocannabinoids reduces the expression of active escape behaviors during an acute stress episode (Patel et al., 2005b).

The purpose of the present study was to assess the contribution of changes in endocannabinoid signaling to the reduction of sucrose consumption that accompanies subchronic stress exposure. Our hypothesis is that subchronic stress recruits endocannabinoid signaling, and that enhanced endocannabinoid signaling opposes the anhedonic effects of stress. We have tested this hypothesis using sucrose consumption to assess reward processing and restraint as a stressor.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Male ICR mice (21-24 g, N=713) were used in these experiments (Harlan, Madison, WI). All animals were housed, five per cage, on a 12 hr light/dark cycle with lights on at 0600 hrs. All studies were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All efforts were made to minimize the number of mice used and their suffering.

2.2. Materials

Graduated glass bottles, stoppers, and drinking tubes were purchased from Ancare Corp. (Bellmore, NY). Sucrose and saccharin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Rimonabant (SR141716) and CP55940 were provided by the NIDA Drug Supply Program (Research Triangle Park, NC). URB597 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). CP55940 and rimonabant were dissolved in an emulphor vehicle consisting of a ratio of 1:1:18 for drug in DMSO-emulphor-saline. URB597 was dissolved in an emulphor vehicle consisting of a ratio of 1:1:8 for drug in DMSO-emulphor-saline. Drug was delivered by i.p. injection in a volume of 1 ml/kg. Control animals received an equivalent i.p. injection of the vehicle without drug. Mice received only a single injection of drug or vehicle that was administered one hr prior to the fluid consumption test.

2.3. Fluid consumption

Mice were habituated to consume either a sucrose (10% w/v) or saccharin (0.1% w/v) solution by providing sucrose or saccharin as the only drinking fluid for 48 hrs. After habituation, baseline sucrose or saccharin preference was measured for five consecutive days. During the daily fluid preference test, which lasted for 60 min, mice had concurrent access to either sucrose (10 % w/v) or saccharin (0.1% w/v) solution and tap water. A 10% w/v sucrose solution was selected since sucrose consumption has been shown to be concentration-dependent, with the highest amount of sucrose consumed at a concentration of 10% w/v (Katz, 1982). Therefore, this assay is biased towards the detection of decreases in sucrose consumption and is less sensitive to increases in consumption. Fluid intake was measured by weighing the bottles before and after the preference test. Sucrose, saccharin, and water consumption was determined by dividing the mass of solution consumed in g by body weight in kg. Sucrose and saccharin preference, measured to account for possible between-group differences in water consumption, was determined by dividing sucrose or saccharin consumption by total fluid consumption. Consistent with previous studies of the effect of stress on the consumption of highly palatable solutions, all mice were deprived of food and water for 20 hrs preceding each fluid preference test (Papp et al., 1993; Sampson et al, 1991; Willner et al., 1987). Immediately after completion of the fluid preference test, mice had ad lib access to food and water for 4 hrs in their home cages.

2.4. Stress procedure

Mice were acclimated to the testing room for 24 hrs prior to experimentation. All mice were marked on their tail once daily for identification. All mice were food and water deprived and subjected to the fluid consumption procedure. Mice were stressed by restraint for 30 min in modified, transparent 50 ml plastic conical tubes with numerous air holes to increase ventilation (Patel et al., 2004). Non-restrained mice were left undisturbed in their home cage during the restraint procedure. In each study, sucrose preference was determined in four groups of mice: mice injected with vehicle 60 min prior to the fluid consumption test without restraint stress (n=9-12 per study); mice injected with vehicle 60 min and restraint stress administered 30 min prior to the fluid consumption test (n=9-12 per study); mice injected with drug 60 min prior to the fluid consumption test without restraint stress (n=9-12 per study); mice injected with drug 60 min and restraint stress administered 30 min prior to the fluid consumption test (n=9-12 per study).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by either Bonferroni post-tests or Tukey's multiple comparison tests. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. An α level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Restraint stress effects on sucrose preference

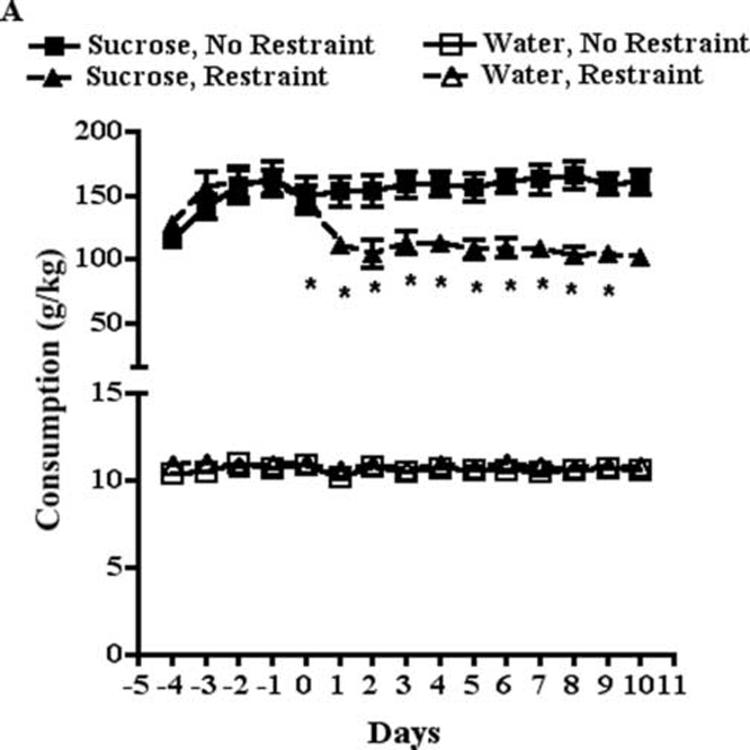

Mice habituated to the fluid consumption procedure drank approximately 3.75 g (140 g/kg body weight) of 10% sucrose solution and approximately 0.25 g (10 g/kg body weight) of water during a 60 min fluid consumption period. Mice exposed to a 30 min restraint episode immediately prior to the fluid consumption test drank approximately 2.40 g (90 g/kg body weight) of 10% sucrose solution and approximately 0.25 g (10 g/kg body weight) of water. A two-way ANOVA of the effect of restraint stress on sucrose consumption over 10 days of restraint revealed that restraint stress significantly decreased sucrose consumption (F[1,281]=78.7, P<0.0001) (Fig. 1A). There was a significant effect for days of restraint (F[14,281]=2.5, P<0.01) on sucrose consumption and a significant restraint stress by days of restraint interaction (F[14,281]=4.0, P<0.0001). A two-way ANOVA of the effect of restraint stress on water consumption revealed that restraint stress had no significant effect on water consumption. There was no significant effect of days of restraint on water consumption and the restraint stress by days of restraint interaction was not significant. Two-way ANOVA of the effects of restraint on sucrose preference over 10 days of restraint revealed a significant effect of restraint stress (F[1,74]=119.6, P<0.0001) and no significant effect of days of restraint on sucrose preference (Fig. 1B). The preference ratio for non-restrained mice habituated to the fluid consumption procedure was typically 0.94, while the preference ratio for mice subjected to a 30 min restraint episode was typically 0.90. Therefore, restraint stress decreased sucrose preference, an effect that does not exhibit habituation in this time frame.

Fig. 1.

A. Restraint for 30 min reduces sucrose but not water consumption in mice. Days refer to days of restraint. Day 0 is the day prior the first restraint episode. * P<0.05 compared to no restraint, Bonferroni post-tests. B. The results in panel A are shown as sucrose preference ratio (sucrose consumed: total fluid consumed). * P<0.05 compared to no restraint, Bonferroni post-tests.

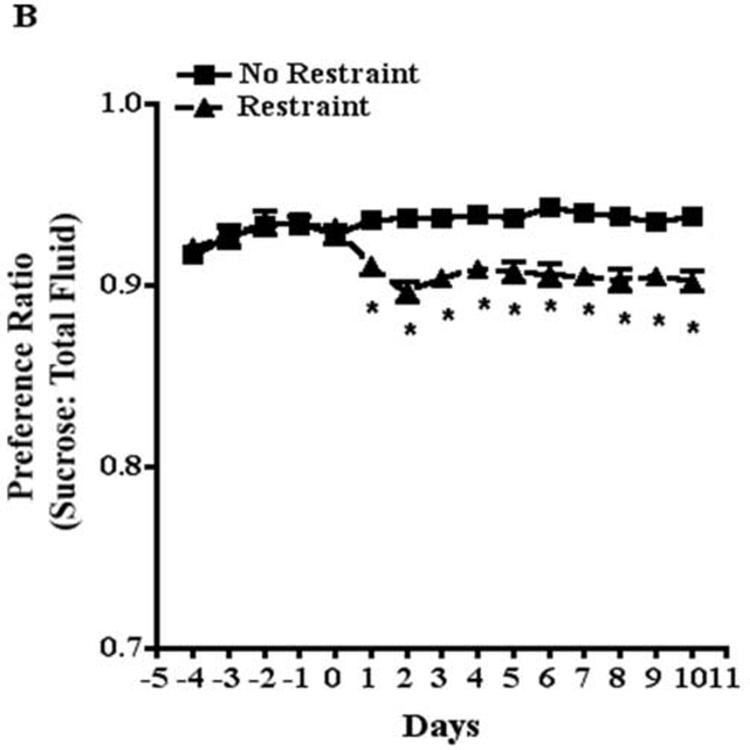

3.2. Effects of food and water deprivation on body weight

Two-way ANOVA of the effects of restraint stress on body weight over time revealed a significant effect of food and water deprivation (F[1,602]=9.1, P<0.01) and a significant effect of days of food and water deprivation (F[13,602]=6.3, P<0.001) on body weight; however, there was no significant interaction between food and water deprivation and time. Importantly, food and water deprivation had a similar effect on non-restrained and restrained mice. There were no significant differences in body weights between non-restrained and restrained mice at any time point during the experiments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of food and water deprivation and restraint on mouse body weight. Mice were weighed daily and food and water deprived for 20 hours per day beginning on day 1. Weights were normalized to the weights on day −2.

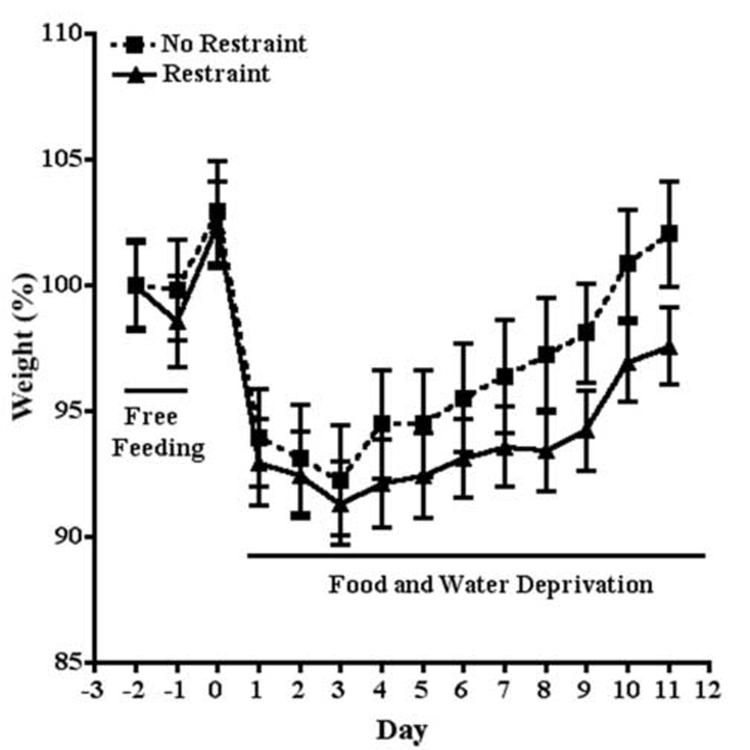

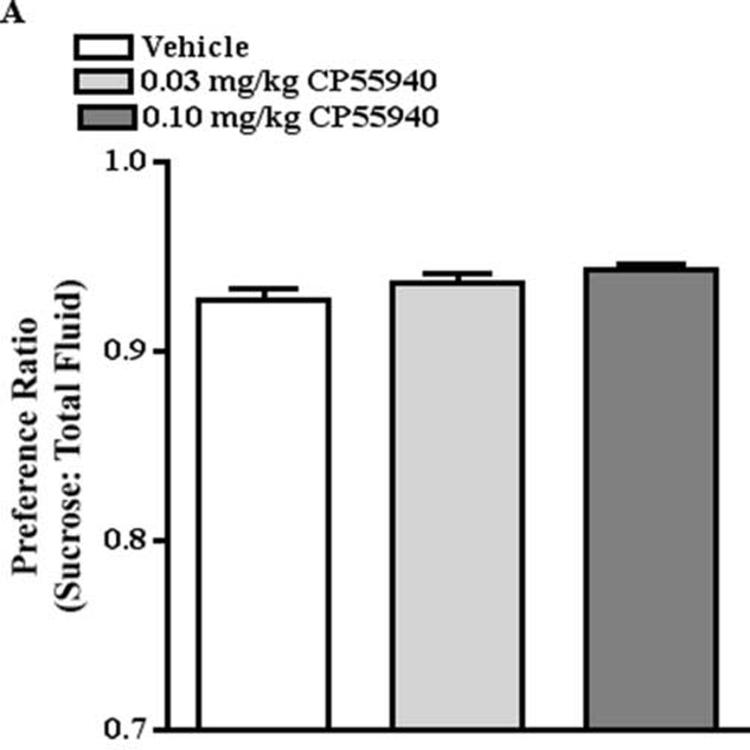

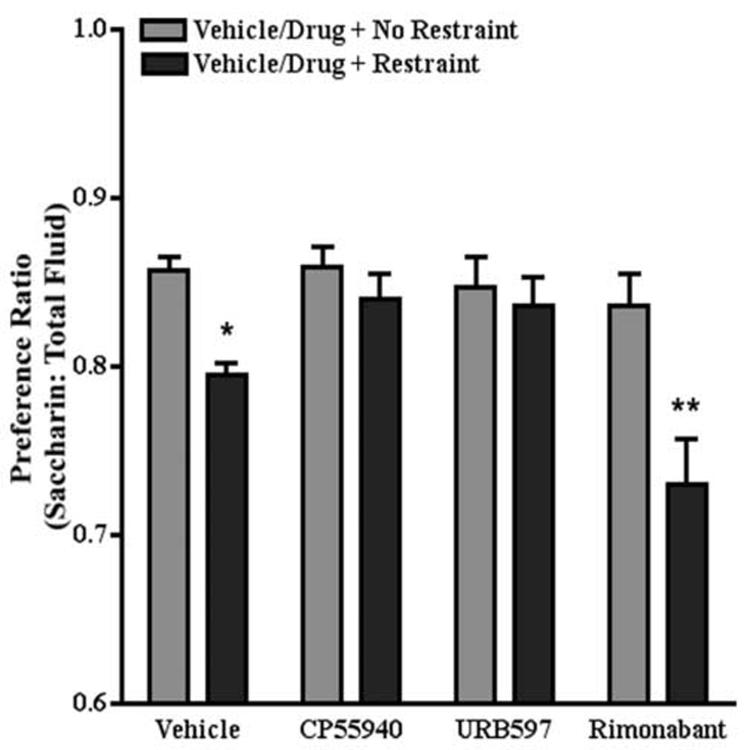

3.3. Effects of CP55940, URB597, and rimonabant on sucrose preference

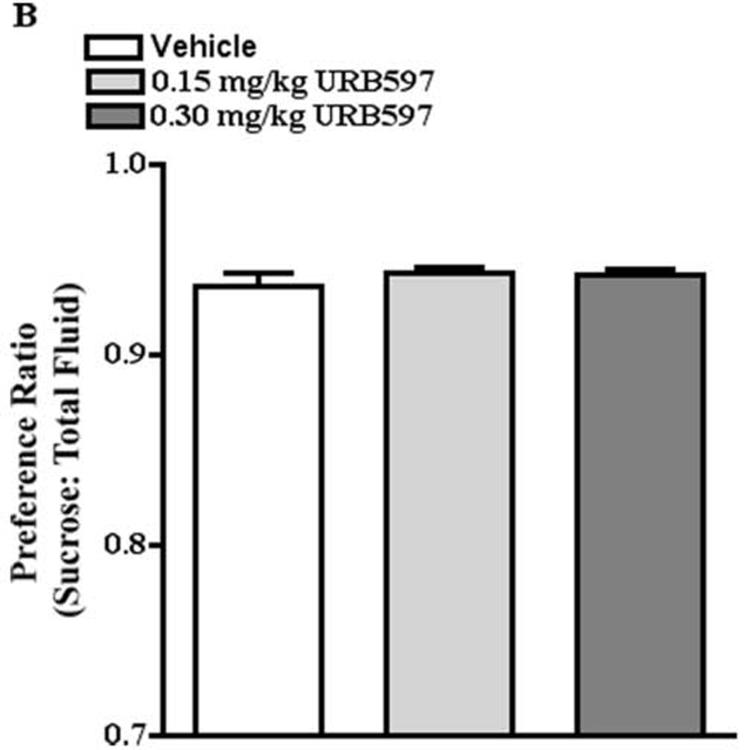

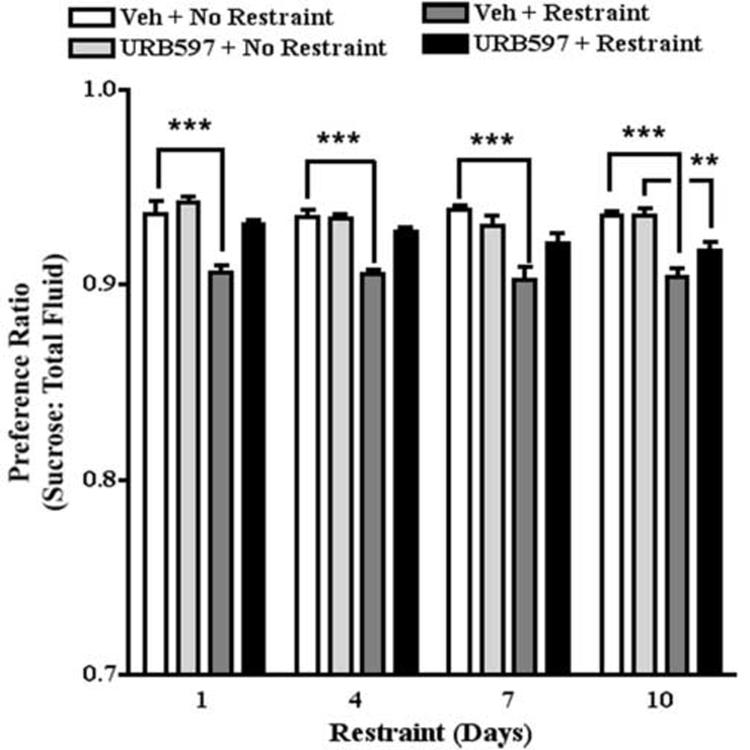

As cannabinoids have well known effects on ingestive behaviors (for review, see Cota et al., 2003; 2006; Fride et al., 2005), it was important to identify doses of a cannabinoid receptor agonist, CP55940, a CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, and a FAAH inhibitor, URB597, that had no effect on sucrose preference to determine the effect of CB1 receptor activation and blockade on stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference. One-way ANOVA revealed that treatment with CP55940 (0.03, 0.10 mg/kg), URB597 (0.15, 0.30 mg/kg), or rimonabant (0.5, 1 mg/kg) had no significant effect on sucrose preference. The preference ratio for mice treated with vehicle and CP55940 was 0.93 and .94, respectively (Fig. 3A). The preference ratio for mice treated with vehicle and URB597 was 0.94 and 0.94, respectively (Fig. 3B). The preference ratio for mice treated with vehicle and rimonabant was 0.94 and 0.94, respectively (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Doses of CP55940, URB597, and rimonabant that had no effect on sucrose preference. A. CP55940 (0.03, 0.10 mg/kg) had no effect on sucrose preference. B. URB597 (0.15, 0.30 mg/kg) had no effect on sucrose preference. C. Rimonabant (0.5, 1 mg/kg) had no effect on sucrose preference.

3.4. Effects of CP55940 on restraint stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference

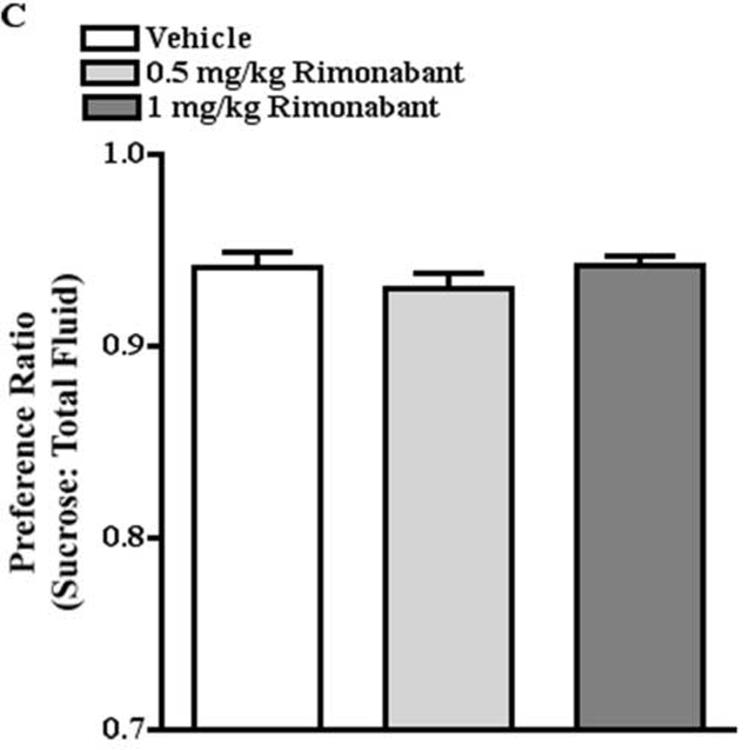

The cannabinoid receptor agonist, CP55940, crosses the blood-brain barrier and produces long-lasting effects on behavior (Howlett et al., 1988; Little et al., 1988). Mice were pretreated with CP55940 (0.03 mg/kg) or vehicle 60 min prior to the fluid consumption test. Restraint was administered 30 min after the drug injection and immediately prior to the fluid consumption test. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of restraint stress on sucrose preference revealed that restraint stress significantly decreased sucrose preference (F[1,72]=108.5, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with vehicle was typically 0.94 and 0.90, respectively. The effects of days of restraint and the restraint by days of restraint interaction were not statistically significant. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of CP55940 on restraint stress-induced decrease in sucrose preference revealed that CP55940 reversed the effect of restraint stress to decrease sucrose preference (F[3,140]=52.2, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for restrained mice treated with CP55940 (0.03 mg/kg) was 0.94. The effects of days of restraint and the CP55940 by days of restraint interaction were not statistically significant. Posthoc analysis confirmed that this dose of CP55940 did not affect sucrose preference in non-stressed mice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The effect of CP55940 on sucrose preference. Restraint stress decreased sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10. CP 55940 blocked stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, but not 10. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, Bonferroni post-tests.

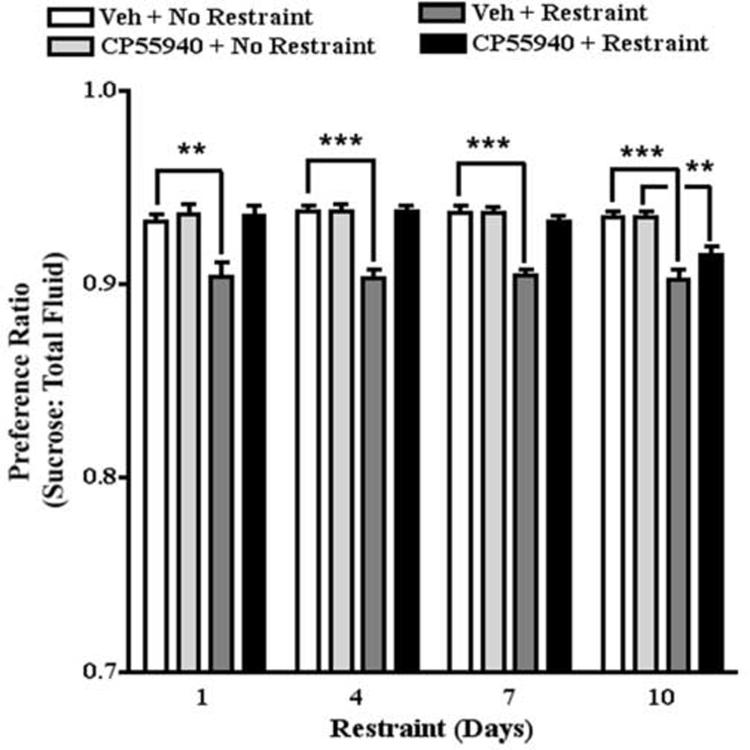

3.5. Effects of URB597 on restraint stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference

The potent FAAH inhibitor, URB597, crosses the blood-brain barrier and produces rapid (i.e., within 30 min) and long-lasting (i.e., at least 6 hrs) effects on brain AEA (Fegley et al., 2005) but not 2-AG content (Kathuria et al., 2003; Patel et al., 2005a). We have shown previously that 0.3 mg/kg URB597 inhibits the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by restraint stress (Patel et al., 2004). Mice were pretreated with 0.3 mg/kg URB597 60 min prior to the fluid consumption test; restraint stress was administered 30 min later. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of restraint stress on sucrose preference revealed that restraint stress significantly decreased sucrose preference (F[1,75]=112.0, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with vehicle was 0.94 and 0.90, respectively. The effects of days of restraint and the restraint by days of restraint interaction were not statistically significant. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of URB597 on restraint stress-induced decrease in sucrose preference revealed that URB597 reversed the effect of restraint stress to decrease sucrose preference (F[3,145]=54.8, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for restrained mice treated with URB597 (0.3 mg/kg) was 0.94. The effects of days of restraint and the URB597 by days of restraint interaction were not statistically significant. Posthoc analysis confirmed that this dose of URB597 did not affect sucrose preference in non-stressed mice (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The effect of URB597 on sucrose preference. Restraint stress decreased sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10. URB597 blocked stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4 and 7 but not 10. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, Bonferroni post-tests.

3.6. Effects of rimonabant on stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference

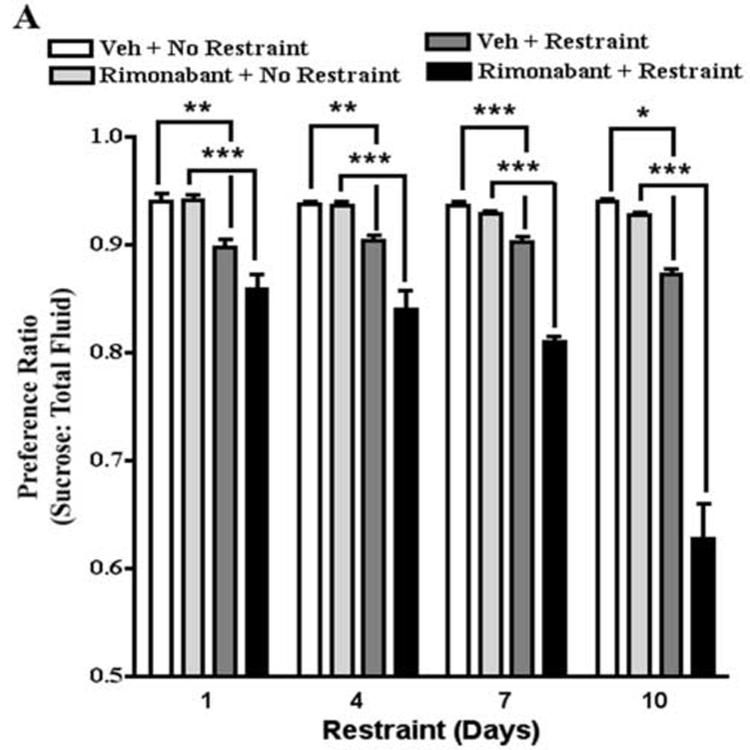

The selective CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, crosses the blood-brain barrier and has a long duration of action (i.e., 6-8 hrs) (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994; 1995). Mice were pretreated with rimonabant (1 mg/kg) 60 min prior to the fluid consumption test and 30 min prior to restraint. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of restraint stress on sucrose preference revealed that restraint stress significantly decreased sucrose preference (F[1,81]=123.7, P<0.0001) (Fig. 6A). The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with vehicle was 0.94 and 0.90, respectively. The effects of days of restraint and the restraint by days of restraint interaction were not statistically significant. Two-way ANOVA of the effect of rimonabant on restraint stress-induced decrease in sucrose preference revealed that rimonabant enhanced the effect of restraint stress to decrease sucrose preference (F[3,161]=156.0, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for restrained mice treated with rimonabant (1.0 mg/kg) was 0.86, 0.84, 0.81, and 0.63 on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10, respectively. The effects of days of restraint and the rimonabant by days of restraint interaction were statistically significant (F[3,161]=29.5, P<0.0001; F[9,161]=19.5, P<0.0001, respectively). Posthoc analysis confirmed that this dose of rimonabant did not affect sucrose preference in non-stressed mice (Fig. 6A). One-way ANOVA revealed that pretreatment with rimonabant accentuated a stress-induced decrease of sucrose preference (F[3,47]=29.3, P<0.0001). Posthoc analyses also revealed that the enhancement of stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference by rimonabant was significantly greater on restraint day 10 compared to restraint days 1, 4, and 7 (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The effect of rimonabant on sucrose preference. A. Restraint stress decreased sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10. Rimonabant enhanced stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, Bonferroni post-tests. B. The effect of rimonabant to enhance stress-induced decreases in sucrose preference was greater on day 10 compared to days 1, 4, and 7. *** p<0.001, Tukey's multiple comparison test.

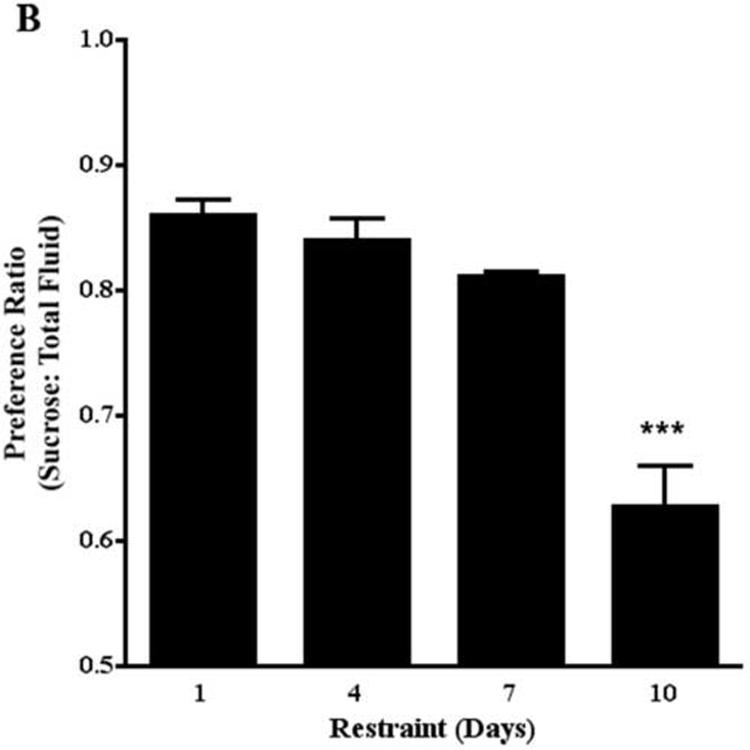

The data above suggest that exposure of mice to 10 consecutive days of restraint recruits endocannabinoid signaling which maintains sensitivity to reward. To explore this question further, mice were either untreated or exposed to 10 restraint episodes. On day 11, mice were injected with either vehicle or rimonabant (1 mg/kg) 60 min prior to the fluid preference test; none of the mice were restrained. One-way ANOVA revealed that pretreatment with rimonabant of mice restrained for 10 days produced a significant reduction in sucrose preference (F[3,44]=31.7, P<0.0001). The preference ratio for non-restrained mice and mice restrained for 10 days and pretreated with rimonabant on day 11 was 0.94 and 0.89, respectively. Posthoc analysis revealed that the mice exposed to restraint for 10 days exhibited a significantly lower sucrose preference on day 11 even though no restraint occurred on that day. The preference ratio for non-restrained mice and mice restrained for 10 pretreated with vehicle on day 10 was 0.94 and 0.92, respectively. Posthoc analysis confirmed that the same dose of rimonabant had no effect on sucrose preference in mice that were never restrained (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of restraint stress and rimonabant on sucrose preference on day 11. Mice exposed to restraint for 10 days exhibited a significantly lower sucrose preference on day 11 even though no restraint occurred on that day. Pretreatment with rimonabant on day 11 of mice restrained for 10 days produced a significant reduction in sucrose preference even though no restraint occurred on that day. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, Bonferroni post-tests.

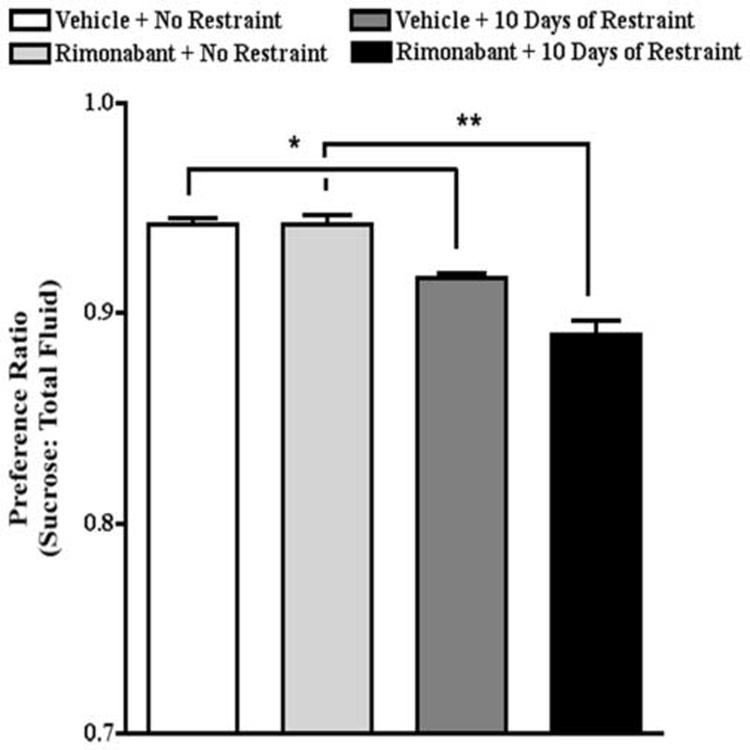

3.7. Stress-induced decreases in saccharin preference

Whereas sucrose is both sweet and has caloric value, saccharin is sweet and has no caloric value. To further explore the role of endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor signaling in stress-induced decreases in the preference for natural rewards, we examined the effects of the same three drugs on stress-induced decreases in saccharin preference. In this study, mice were offered 0.1 % saccharin and water in a two bottle choice paradigm. All other aspects of the experiment were identical to the sucrose preference studies. Restraint was applied one time and fluid consumption was determined immediately after. Control mice exhibited a greater preference for saccharin than water (preference ratio = 0.86). Two-way ANOVA revealed an significant effect of restraint stress (F[3,74]=6.4, P<0.0001), drug (CP55940, URB597, or rimonabant) pretreatment (F[1,74]=16.8, P<0.0001) and a significant interaction between restraint stress and drug pretreatment (F[3,74]=3.5, P<0.05). The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with vehicle was 0.86 and 0.80, respectively. In agreement with the sucrose preference data, posthoc analyses revealed that restraint did not produce a significant reduction in saccharin preference in mice pretreated with either CP55940 (0.03 mg/kg) or URB597 (0.3 mg/kg). The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with CP55940 was 0.86 and 0.84, respectively. The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with URB597 was 0.85 and 0.84, respectively. Posthoc analysis revealed that mice pretreated with rimonabant exhibited a significant reduction in saccharin preference. The preference ratio for non-restrained and restrained mice treated with rimonabant was 0.84 and 0.73, respectively. However, unlike its effect on sucrose preference, rimonabant did not enhance stress-induced decreases in saccharin preference (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Acute effects of CP55940, URB597, and rimonabant on saccharin preference. Restraint stress decreased saccharin preference. Both CP55940 and URB597 blocked a stress-induced decrease in saccharin preference. Rimonabant did not enhance a stress-induced decrease in saccharin preference. * p <0.05, ** p <0.001 compared to vehicle- or drug-treated + no restraint, Bonferroni post-tests.

4. Discussion

Earlier reports had indicated that exposure to a series of unpredictable mild (Monleon et al., 1995; Willner et al., 1987), relatively intense (Katz, 1982), or uncontrollable stressors (Griffiths et al., 1992) results in persistent reductions in the consumption of sweet solutions. Likewise, we find that restraint stress causes a persistent decrease in sucrose preference that does not vary across days of restraint, suggesting that behavioral adaptation to repeated exposure to restraint stress did not occur within 10 days of restraint. Moreover, in agreement with previous reports (Ayensu et al., 1995; Willner et al., 1987), caloric content seems to be unimportant since similar effects of restraint stress are observed in animals consuming a calorie-free, saccharin solution.

Contrary to a previous report (Forbes et al., 1996), in our study, the decrease in sucrose preference in food-deprived and stressed mice is not due to a decrease in body weight. The use of the two-bottle choice paradigm allows for the determination of sucrose preference rather than the absolute amount of sucrose consumed; sucrose preference was unaffected by changes in body weight (compare Fig. 1B and 2). Both sucrose consumption normalized to body weight and sucrose preference were significantly reduced by an acute exposure to restraint stress prior to the fluid consumption test. Thus, restraint stress causes a decreased sensitivity to natural reward.

Since CB1 receptor agonists enhance voluntary sucrose consumption (Kirkham and Williams, 2001) and CB1 receptor antagonists decrease sucrose consumption (Higgs et al., 2003), doses of CP55940, rimonabant, and URB597, that had no effect on sucrose preference in stress-naïve mice were identified. This allowed for the determination of the effects of CB1 receptor activation and blockade on stress-induced decreased sensitivity to natural reward rather than on baseline consumption. Pretreatment with these doses of CP55940 or URB597 blocked restraint stress-induced decreased sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, and 7, but not 10. By contrast, pretreatment with a dose of rimonabant that had no effect on sucrose preference in unstressed mice accentuated restraint stress-induced decreased sucrose preference on restraint days 1, 4, 7, and 10. This finding is in agreement with the report that CB1 receptor deletion decreased sucrose solution intake in mice chronically exposed to unpredictable mild stressors (Martin et al., 2002). The finding that CP55940, URB597, and rimonabant had qualitatively similar effects on stress-induced decreases in sucrose and saccharin preference suggests that the caloric content of the solution was not an important factor. Thus, while CB1 receptor activation blocks, CB1 receptor blockade exacerbates stress-induced decreased sensitivity to natural reward.

We hypothesize that endocannabinoids modulate decreased sensitivity to natural reward induced by acute restraint stress by regulating the central stress response. In support of this hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that endocannabinoids modulate hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis function (Haller et al., 2004; Manzanares et al., 1999; Patel et al., 2004). In particular, earlier studies from our laboratory (Patel et al., 2004) demonstrated that CB1 receptor blockade potentiates restraint stress-induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activation and neuronal activity in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, and CB1 receptor activation blocks restraint stress-induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activation. These data are consistent with the effects of CB1 receptor agonists and antagonists to affect stress-induced sucrose preference reported herein.

We hypothesize that a global function for endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor signaling is to dampen stress-induced behavioral changes, including the expression of active escape behaviors during acute and repeated restraint stress episodes (Patel et al., 2005b), immobility time in a tail suspension test and swimming time in a forced swim test (Gobbi et al., 2005), and decreased sensitivity to natural reward. Our data is in accord with previous research that demonstrated the protective role of the endocannabinoids becomes more pronounced as the stress is repeated. While a single exposure to restraint stress had no effect on 2-AG content in the limbic forebrain and amygdala, that same restraint exposure produced a large increase in 2-AG content in the limbic forebrain and amygdala following the fifth restraint episode (Patel et al., 2005b). Thus, 2-AG content in the limbic forebrain and amygdala exhibit sensitization to repeated restraint exposure. While CP55940 and URB597 both blocked the effects of restraint to reduce sucrose preference on day 1, these drugs were ineffective on day 10. There are two possible explanations for this change: first, the CB1 receptor no longer plays a role in stress-induced effects on reward or, second, the CB1 receptor is maximally activated such that further agonist treatment produces no effect. The finding that CB1 receptor blockade on day 10 results in a reduction in sucrose preference that is significantly greater than its effect on day 1 supports the second scenario, i.e. CB1 receptors maximally activated and required for the maintenance of sucrose preference in the face of 10 days of restraint stress. The finding that after 10 days of restraint, rimonabant, which had no effect on sucrose preference in the absence of restraint, significantly reduced sucrose preference in the absence of acute stress suggest that a global increase in endocannabinoid tone induced by subchronic restraint stress persists for at least 24 hours after the termination of the stressor.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, restraint stress decreases sensitivity to natural reward regardless of caloric value. The effect of restraint to decrease sensitivity to natural reward is regulated by activity at the CB1 receptor such that CB1 receptor activity opposes the effects of stress. The endocannabinoids most likely modulate the decreased sensitivity to natural reward induced by acute and subchronic restraint stress by regulating the central stress response. Furthermore, when the stress is repeated for 10 days, our data suggest that the endocannabinoid system is vital for the maintenance of sucrose consumption since CB1 receptor blockade results in a profound reduction in sensitivity to reward. In addition, endocannabinoid activation of the CB1 receptor is maximal at day 10 since exogenous CB1 receptor agonists or indirect agonists do not affect sucrose preference. The mechanism for this change is not clear, but could involve either increased endocannabinoid content or decreased CB1 receptor expression, for example. We hypothesize that endocannabinoid activation of CB1 receptors protects animals from stress-induced decreased sensitivity to natural reward and those pharmacological agents that produce a global increase in endocannabinoid tone could reduce anhedonia, a core symptom of major depressive disorder and defining feature of melancholia (America Psychiatric Association, 1994). Clinically, these data could have implications for changes in motivation that occur in human neuropsychiatric disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, drug abuse, and schizophrenia.

Acknowledgements

These studies were funded by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA16967 and F32 DA16510).

Abbreviations

- AEA

N-arachidonylethanolamine

- 2-AG

2-arachidonylglycerol

- CB1

central cannabinoid receptor

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alger BE. Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:247–86. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ayensu WK, Pucilowski O, Mason GA, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Janowsky DS. Effects of chronic mild stress on serum complement activity, saccharin preference, and corticosterone levels in Flinders lines of rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:165–69. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00204-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braida D, Pozzi M, Cavallini R, Sala M. Conditioned place preference induced by the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940: interaction with the opioid system. Neuroscience. 2001a;104:923–6. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braida D, Pozzi M, Parolaro D, Sala M. Intracerebral self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55,940 in the rat: interaction with the opioid system. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001b;413:227–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1048–57. doi: 10.1038/nn1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Patel S, Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoids in neuroimmunology and stress. Current Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:657–65. doi: 10.2174/156800705774933023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer JF, Wassum KM, Heien ML, Phillips PE, Wightman RM. Cannabinoids enhance subsecond dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of awake rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4393–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0529-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Vicennati V, Stalla GK, Pasquali R, et al. Endogenous cannabinoid system as a modulator of food intake. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:289–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Tschop MH, Horvath TL, Levine AS. Cannabinoids, opioids and eating behavior: the molecular face of hedonism? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:85–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch DG, Chin SA. Enzymatic synthesis and degradation of anandamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:791–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90486-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegley D, Gaetani S, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, et al. Characterization of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor cyclohexyl carbamic acid 3′-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl ester (URB597): effects on anandamide and oleolylethanolamide deactivation. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 2005;313:352–58. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes NF, Steward CA, Matthews K, Reid IC. Chronic mild stress and sucrose consumption: validity as a model of depression. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1481–84. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Bregman T, Kirkham TC. Endocannabinoids and food intake: newborn suckling and appetite regulation in adulthood. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:225–34. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL, Paredes W, Smith D, Donner A, Milling C, Cohen D, et al. Facilitation of brain stimulation reward by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;96:142–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02431546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi G, Bambico FR, Mangieri R, Bortolato M, Campolongo P, et al. Antidepressant-like activity and modulation of brain monoaminergic transmission by blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18620–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju SK, Ueda N, Yamaguchi H, Yamamoto S. Anandamide amidohydrolase reacting with 2-arachidonoylglycerol, another cannabinoid receptor ligand. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J, Shanks N, Anisman H. Strain-specific alterations in consumption of a palatable diet following repeated stressor exposure. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;42:219–27. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90519-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Varga B, Ledent C, Barna I, Freund TF. Context-dependent effects of CB1 cannabinoid gene disruption on anxiety-like and social behaviour in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1906–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S, Williams CM, Kirkham TC. Cannabinoid influences on palatability: microstructural analysis of sucrose drinking after delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, anandamide, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol and SR141716. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:370–77. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Milne GM. Nonclassical cannabinoid analgetics inhibit adenylate cyclase: development of a cannabinoid receptor model. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, et al. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RJ. Animal model of depression: pharmacological sensitivity of a hedonic deficit. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;16:965–68. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham TC, Williams CM. Synergistic effects of opioid and cannabinoid antagonists on food intake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;153:267–70. doi: 10.1007/s002130000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, et al. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–04. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore M, Vorel SR, Lowinson J, Gardner EL. Conditioned place preference induced by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol: comparison with cocaine, morphine, and food reward. Life Sci. 1995;56:2073–80. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Hawkins EG, Griffin G, Cravatt BF. Pharmacological activity of fatty acid amides is regulated, but not mediated, by fatty acid amide hydrolase in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:73–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PJ, Compton DR, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Martin BR. Pharmacology and stereoselectivity of structurally novel cannabinoids in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247:1046–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Nicholson KL, Martin BR, Balster RL. Failure of delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and CP 55,940 to maintain intravenous self-administration under a fixed-interval schedule in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:219–25. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199404000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanares J, Corchero J, Fuentes JA. Opioid and cannabinoid receptor-mediated regulation of the increase in adrenocorticotropin hormone and corticosterone plasma concentrations induced by central administration of delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats. Brain Res. 1999;839:173–79. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martellotta MC, Cossu G, Fattore L, Gessa GL, Fratta W. Self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 in drug-naive mice. Neuroscience. 1998;85:327–30. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behaviour. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;159:379–87. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor IS, Issakidis CN, Prior G. Aversive effects of the synthetic cannabinoid CP 55,940 in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53:657–64. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monleon S, D'Aquila P, Parra A, Simon VM, Brain PF, Willner P. Attenuation of sucrose consumption in mice by chronic mild stress and its restoration by imipramine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;117:453–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02246218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Mizushima I, Yoneda N, Zimmer A, Kano M. Presynaptic cannabinoid sensitivity is a major determinant of depolarization-induced retrograde suppression at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3864–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03864.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M, Willner P, Muscat R. Behavioural sensitization to a dopamine agonist is associated with reversal of stress-induced anhedonia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110:159–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02246966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Gillies T. THC-induced place and taste aversions in Lewis and Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:71–78. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Carrier EJ, Ho WS, Rademacher DJ, Cunningham S, Reddy DS, et al. The postmortal accumulation of brain N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) is dependent on fatty acid amide hydrolase activity. J Lipid Res. 2005a;46:342–49. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400377-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Cullinan WE, Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoid signaling negatively modulates stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5431–38. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ. Inhibition of restraint stress-induced neuronal and behavioural activation by endogenous cannabinoid signalling. Eur J Neurosci. 2005b;21:1057–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Heaulme M, Alonso R, Shire D, Congy C, et al. Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of SR141716A, the first potent and selective brain cannabinoid receptor antagonist. Life Sci. 1995;56:1941–47. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Heaulme M, Shire D, Calandra B, Congy C, et al. SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:240–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00773-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson D, Willner P, Muscat R. Reversal of antidepressant action by dopamine antagonists in an animal model of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104:491–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02245655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Cline BH, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Spanagel R. Reduced sensitivity to reward in CB1 knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:223–32. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Peña MC, Tsou K, Delay ER, Hohman AG, Force M, Walker JM. Endogenous cannabinoids as an aversive or counter-rewarding system in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;223:125–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1995;215:89–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi RN, Singer G. Cross self-administration of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and D-amphetamine in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1981;14:395–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Pontieri FE, Di Chiara G. Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common mu1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science. 1997;276:2048–50. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Maldonado R. A behavioural model to reveal place preference to delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;147:436–38. doi: 10.1007/s002130050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Dykstra LA. The role of CB1 receptors in sweet versus fat reinforcement: effect of CB1 receptor deletion, CB1 receptor antagonism (SR141716A) and CB1 receptor agonism (CP-55940) Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:381–88. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200509000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Towell A, Sampson D, Sophokleous S, Muscat R. Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;93:358–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00187257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Kunos G, Nicoll RA. Presynaptic specificity of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;31:453–62. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–92. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]