Abstract

The endothelium is one of the largest cellular compartments of the human body and has a high proliferative potential. However, angiosarcomas are among the rarest malignancies. Despite this interesting contradiction, data on growth and angiogenesis control mechanisms of angiosarcomas are scarce. In this study of 19 angiosarcomas and 10 benign vascular control lesions we investigated the sequence and expression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene and the expression of the mdm-2 proto-oncogene, which is a negative regulator of p53 activity and of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), whose expression, among other factors, is regulated by the p53/MDM-2 pathway. Ten sarcomas (53%) exibited clear nuclear p53 protein accumulation. Two of these cases revealed mutations in the sequence-specific DNA binding domain of the p53 gene. Thirteen angiosarcomas (68%) showed an increased amount of MDM-2 protein. Elevated expression of p53 and MDM-2 protein correlated with increased VEGF expression, which was found in nearly 80% of the angiosarcoma cases. Negative or clearly lower immunostaining was obtained in cases from the benign control collective. Only one case of a juvenile hemangioma reached the cutoff value of p53 positivity coincidentally with high VEGF expression. Our data suggest that the p53/MDM-2 pathway is impaired in about two-thirds (14/19) of the angiosarcomas. This may be a key event in the pathogenesis of human angiosarcomas. The increased VEGF expression observed supports this hypothesis.

More than a trillion (1012) endothelium cells line the inside of vessels and cover an area of approximately 1000 m 2 in a 70-kg adult. 1 Endothelial cells are normally resting but changes in the net balance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors can shift them from almost complete quiescence, with turnover times as slow as 1000 days, 2 into a phase of rapid growth. 3 Thus an immense number of cells in the body have the potential to switch from a resting status to rapid proliferation in active angiogenesis. However, malignant transformation of endothelial cells is an unusual event. In fact, angiosarcomas are among the rarest forms of human neoplasms. They comprise less than 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas. 4 The reasons for this remarkably low incidence are unknown.

One of the most frequently affected growth control mechanisms known to date in human malignancies is the p53 tumor suppression pathway. Nearly all of the different kinds of human malignancies analyzed thus far were shown to contain alterations in the p53 gene and the p53 regulating pathway in a considerable percentage of cases. 5-9 The p53 status of angiosarcomas is only sparsely documented compared to that of other human malignancies. In carcinoma cells p53-dependent growth control is often impaired by missense mutations in one allele and the loss of the other, resulting in the accumulation of defective p53 protein. Alternatively, wild-type-p53 protein (wt-p53) can be functionally inactivated by binding to the cellular murine double minus-2 protein (MDM-2). This protein forms a tight complex with both mutant and wt-p53 and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Recent studies showed that the mdm-2 gene amplification has effects similar to p53 mutation. Thus, genetic alterations of either p53 or mdm-2 obviously represent alternative mechanisms for inactivating the same growth suppression pathway and overexpression of MDM-2 can lead to an escape from p53-regulated growth control as well. 10,11 In fact, the human mdm-2 gene is frequently altered in human sarcomas and several studies demontrated that sarcomas that maintain wild-type p53 alleles overexpress MDM-2. 12-16 To date, angiosarcomas have not been investigated for MDM-2 status. Therefore the aim of the present study was to investigate the role of p53 and MDM-2 in the pathogenesis of angiosarcomas. We present a collection of 19 angiosarcoma cases in comparison to 10 benign vascular control lesions. We evaluated p53 expression by immunohistochemistry, investigated the p53 gene structure in the area of the so-called mutation hot spots (exon 5 to 9) by sequence analysis, and confirmed the sequence data by a denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis assay (DGGE). MDM-2 was studied by immunohistochemistry. The study was completed by investigating the expression of vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF) because a link between p53 activity and VEGF expression was recently shown. 17,18

Materials and Methods

Patients

The angiosarcoma study group (n = 19) was composed of 11 females and 8 males with an average age of 49 years (range, 25–88 years). Six angiosarcomas (cases 3, 4, 7, 8, 15, and 19) were located in the breast. Five angiosarcomas (cases 2, 5, 6, 10, and 18) were found in the soft tissue of arms and legs, one tumor (case 1) occurred in the head, and one (case 17) in the trunk. Three patients (cases 11, 12, and 13) showed a primary tumor location in the thyroid. One patient with angiosarcomatous infiltration of the lung (case 14) exhibited no other primary tumor localization. One case originated in the heart and great vessels (case 9); another arose in the sternum (case 16). The known facultative predisposing factors for the development of angiosarcoma in the cases studied were chronic lymphedema (cases 2 and 6) and postirradiation status (cases 10 and 13). Thyroid angiosarcomas (cases 11, 12, and 13) are known to show a predilection for mountainous regions of the world (such as the Bavarian alpine region) with iodine deficiency and development of long-standing nodular goiter. 19 In none of the cases was there any indication of occupational exposure to thorotrast (thorium dioxide), arsenic solutions, or vinyl chloride, all of which may be associated with the development of angiosarcomas. 20-22

For comparison and negative control, 10 specimens of benign vascular lesions and normal skin were included in the study. The control group (n = 10) consisted of five females and five males with an average age of 31 years (range, 10 days to 69 years). For detailed information regarding patients’ age, sex, and tumor localization, see Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ .

Table 1.

Angiosarcoma Group: Patient Characteristics, Results of Immunohistochemical Staining, and p53 Gene Sequence Analysis (Exons 5–9)

| Case No. | Age (Years) | Sex | Tumor Location | Histol. Grad (Coindre) | Immunohistochemistry Percentage of positive cells (PP*)/Staining intensity (SI†) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 (PP/SI) | MDM-2 (PP/SI) | VEGF (PP/SI) | |||||

| 1 | 58 | M | head | 3 | 5/3 mutant‡ | 5/3 | 5/3 |

| 2 | 68 | F | upper arm | 2 | 3/2 wild-type | 3/3 C+¶ | 5/2 |

| 3 | 25 | F | breast | 3 | 4/3 wild-type | 5/3 | 5/2 |

| 4 | 54 | F | breast | 3 | 1/2 wild-type | 1/1 | 2/1 |

| 5 | 70 | M | lower leg | 2 | 2/3 wild-type | 2/3 C+ | 5/2 |

| 6 | 37 | F | (U/L) leg | 3 | 2/2 wild-type | 2/1 | 5/2 |

| 7 | 88 | F | breast | 3 | 1/2 wild-type | 2/2 C+ | 5/3 |

| 8 | 31 | F | breast | 3 | 5/3 mutant§ | 3/2 | 5/3 |

| 9 | 44 | M | heart/aorta | 3 | 4/2 wild-type | 4/2 | 5/3 |

| 10 | 41 | M | upper leg | 3 | 5/3 wild-type | 5/3 | 5/3 |

| 11 | 42 | F | thyroid | 2 | 2/2 wild-type | 3/3 C+ | 5/2 |

| 12 | 60 | M | thyroid | 3 | 2/3 wild-type | 3/3 | 5/2 |

| 13 | 59 | F | thyroid | 3 | 3/2 wild-type | 5/3 | 4/2 |

| 14 | 67 | F | lung | 3 | 1/2 wild-type | 4/2 | 3/2 |

| 15 | 61 | F | breast | 2 | 1/2 wild-type | 1/1 | 0/0 |

| 16 | 29 | M | sternum | 2 | 5/2 wild-type | 2/3 C+ | 5/3 |

| 17 | 35 | M | trunk | 2 | 3/3 wild-type | 4/3 | 5/3 |

| 18 | 37 | M | upper leg | 3 | 4/3 wild-type | 4/3 | 5/3 |

| 19 | 33 | F | breast | 2 | 2/1 wild-type | 5/3 | 5/2 |

*PP: 0 = negative; 1 = 1–20%; 2 = 21–40%; 3 = 41–60%; 4 = 61–80%; 5 = 81–100%.

†SI: 0 = negative, 1 = light, 2 = intermediate, 3 = intense staining.

‡sequence data: exon 6, codon 197, nucleotide change: GTG → GGG, amino acid change Val → Gly.

§sequence data: exon 8, codon 274, nucleotide change: GTT → CTT, amino acid change Val → Leu.

¶cytoplasmic staining.

Table 2.

Control Group: Patient Characteristics and Results of Immunohistochemical Staining

| Case No. | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Tumor Location | Immunohistochemistry Percentage of positive cells (PP*)/Staining intensity (SI†) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 (PP/SI) | MDM-2 (PP/SI) | VEGF (PP/SI) | |||||

| C1 | 10 days | M | Cystic lymphangioma | Head | 0/0 | 1/1 | 2/1 |

| C2 | 57 years | F | Granulation tissue | Oropharynx | 1/1 | 2/1 | 2/2 |

| C3 | 31 years | F | Granulation tissue | Oropharynx | 2/2 | 1/1 | 2/2 |

| C4 | 69 years | F | Granulation tissue | Trunk | 1/1 | 2/2 | 2/1 |

| C5 | 38 years | M | Hemangioma | Upper leg | 1/2 | 3/1 | 3/1 |

| C6 | 6 months | M | Juvenile hemangioma | Head | 3/2 | 2/1 | 5/3 |

| C7 | 15 years | F | Angiofibroma | Nasopharynx | 1/1 | 2/1 | 3/1 |

| C8 | 20 years | M | Skin | Lower leg | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 |

| C9 | 50 years | M | Skin | Upper leg | 0/0 | 1/1 | 2/1 |

| C10 | 28 years | F | Skin | Arm | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 |

*PP: 0 = negative; 1 = 1–20%; 2 = 21–40%; 3 = 41–60%; 4 = 61–80%; 5 = 81–100%.

†SI: 0 = negative, 1 = light, 2 = intermediate, 3 = intense staining.

Histopathology

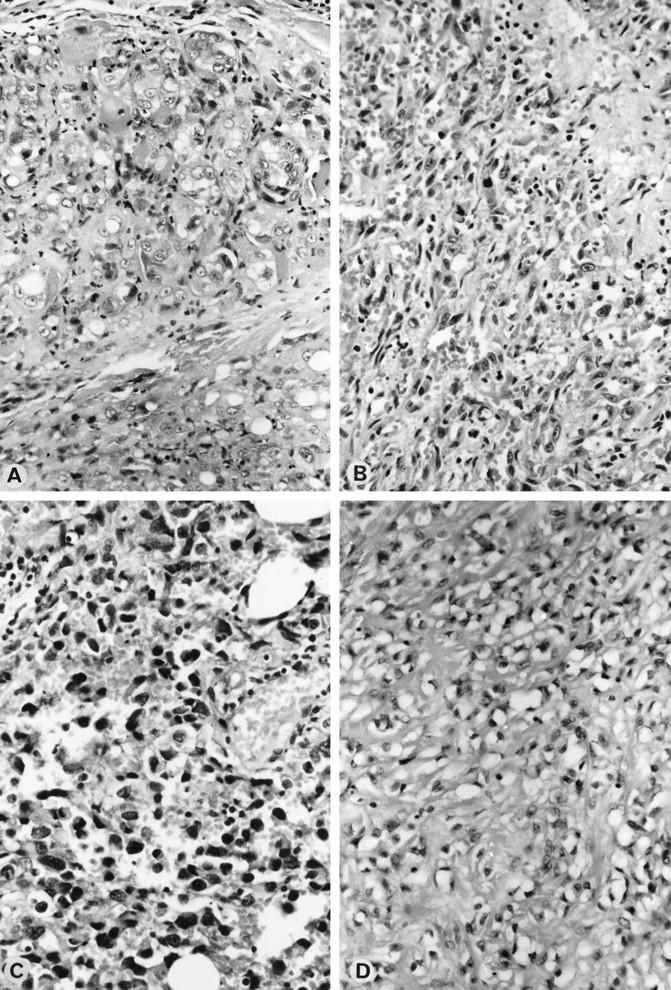

Surgical specimens of angiosarcomas, benign vascular lesions, and normal skin were collected at the Munich University Institute of Pathology between 1983 and 1996. The material had been fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 24 to 48 hours and processed routinely in a low-melting-point paraffin wax (Paraplast, Vogel, Giessen, Germany). Basic morphological diagnosis and classification of the cases were carried out according to the criteria of Enzinger and Weiss 4 as well as to the AFIP and WHO criteria corresponding to the affected organs (breast, 23,24 thyroid, 19 lung, 25 heart and great vessels, 26,27 and bone). 28 Figure 1, A through D ▶ shows the basic morphology of these cases. Angiosarcomas of Kaposi’s type were not included in this study. A panel of vascular markers (antibodies to FVIII (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark), CD34 (Serotec, Oxford, UK), CD31 (Dako), and Ulex Europeus-Antigen (Dako)) were used for immunohistochemical confirmation of the diagnosis. Other neoplasms that may legitimately affect the differential diagnosis in a given case were ruled out using additional antibodies (Cytokeratin-Antigen (Dako), Smooth Mus-cle Aktin-Antigen (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), Desmin-Antigen (Dako), and S100-Antigen (Dako)). From the panel of vascular markers the CD 31 antigen, also termed platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, seemed to be the most sensitive and specific antigen for endothelial differentiation. According to the literature, all studied benign and malignant vascular tumors expressed this membrane protein, whereas more than 100 soft-tissue tumors of nonvascular origin did not. 29 For this reason cases which met the basic morphological criteria and clearly expressed this sensitive vascular marker were accepted as angiosarcomas and included in this study. Histopathological tumor grading was carried out according to Coindre. 30

Figure 1.

Morphological pattern of angiosarcomas. A: Angiosarcoma (case 18). H&E Magnification, ×265. B: Angiosarcoma (case 8). H&E Magnification, ×265. C: Angiosarcoma (case 12). H&E Magnification, ×265. D: Angiosarcoma (case 10). H&E Magnification, ×165

Histopathological diagnoses of the control group were as follows: cystic lymphangioma (case C1), granulation tissue (cases C2, C3, and C4), capillary hemangioma (case C5), cellular hemangioma of infancy/juvenile hemangioma (case C6) and angiofibroma (case C7), and normal skin (cases C8, C9, and C10).

Immunohistochemistry

Consecutive 3-μm sections were cut and mounted on sialinized slides (Superfrost Plus, Menzel-Gläser, Braunsischweig, Germany). Sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated. For antigen retrieval, sections were immersed in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (p53, MDM-2), or Target Retrival Solution (TRS, Dako S1700) (VEGF), heated three times in a microwave oven (800 W) for a total of 30 minutes and allowed to cool in the buffer for 20 minutes. Immunohistochemical studies were performed with a sensitive standard immunohistochemical streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase technique 31,32 using a commercially available staining kit (Universal Dako LSAB-1 KIT/K 0681 Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). Sections were immersed 2 × 5 minutes in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6, after which the endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 7.5% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes before the slides were rinsed and returned to Tris buffer for 2 × 5 minutes. Sections were incubated with Blocking Reagent (LSAB-1 KIT, Dako) for 10 minutes and then coated with primary monoclonal mouse antibody for 60 minutes. The DAKO-p53 antibody, DO-7, recognizes an epitope in the N terminus of the human p53 protein between amino acids 19 and 26. This p53 antibody was used in a final working concentration of 8 μg/ml. The MDM-2 antibody (IF2, Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA), which recognizes an epitope in the amino terminal portion of the 491 AA human MDM-2 protein, was used in a final working concentration of 10 μg/ml. The purified polyclonal rabbit VEGF antibody (Dianova Calbiochem, PC 37), raised against a peptide from the N-terminus region of VEGF, was used in a final working concentration of 10 μg/ml. After incubation with the primary antibody the sections were washed for 2 × 5 minutes in Tris buffer. They were then coated with Link Antibody (LSAB-1 KIT, Dako) for 30 minutes, rinsed, immersed in Tris buffer for 2 × 5 minutes, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin-biotin complex (LSAB, Dako) for 30 minutes. The sections were stained by 3-amino-9-ethylcarbarol (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 15 minutes, rinsed, and counterstained with Mayer’s hemalaun. To ensure specificity and for a control of background staining, controls were included in all staining runs. The primary antibody was replaced with bovine serum albumin in these controls and no immunohistochemical staining was observed.

Analysis and Quantification of the Immunohistochemical Results

Scoring was done according to studies of Remmele and coworkers. 33 This method has been shown to be valid in routine morphology (estrogen and progesterone receptor analysis on breast cancer). The results were organized in six categories based on total percentage of cells staining positively (PP), as follows: Group 0 = negative; Group 1 = 1–20%; Group 2 = 21–40%; Group 3 = 41–60%; Group 4 = 61–80%; Group 5 = 81–100%. The results were further scored for staining intensity (SI) in 4 categories (groups 0–3): negative, light, intermediate, or intense staining.

The documentation of immunohistochemical staining was evaluated independently by two of the authors (CZ, MR). The interobserver variability was low. Questionable cases were reviewed simultaneously by the observers and a final score agreed by discussion.

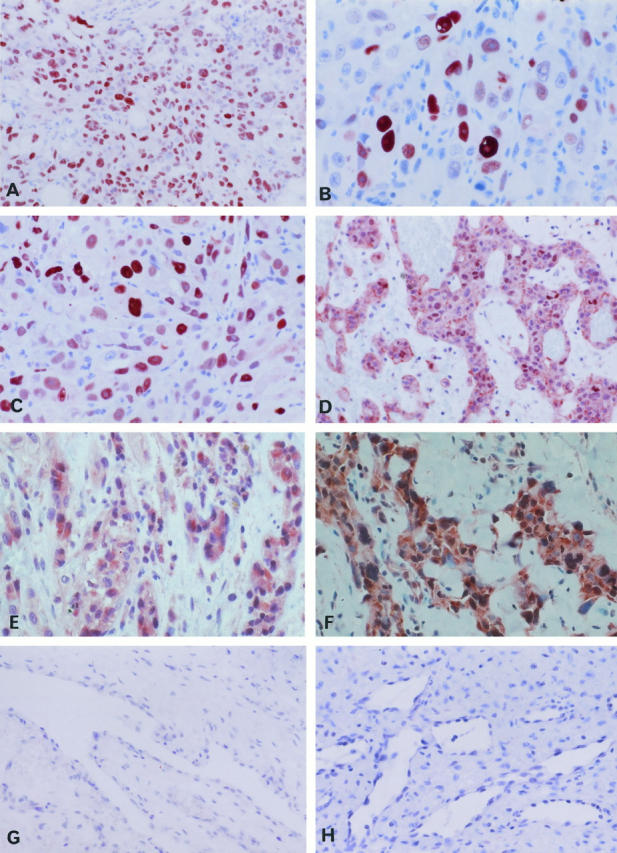

The results clearly show several cases in the benign control group with a definite negative immunoreaction as well as angiosarcomas with intense staining, as documented in Figure 2 ▶ . Because we could refer to negative and positive controls inside our study group there was no need for further external positive controls. Benign control cases and angiosarcomas were immunohistochemically investigated together and all cases were prepared according to the same standardized method, permitting consistent analysis of staining patterns and intensity.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression pattern of p53, MDM-2 protein and VEGF. A: Angiosarcoma (case 1), immunolocalization of p53. Magnification, ×180. B: Angiosarcoma (case 17), immunolocalization of p53. Magnification, ×310. C: Angiosarcoma (case 10), nuclear immunolocalization of MDM-2. Magnification, ×180. D: Angiosarcoma (case 16), nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of MDM-2. Magnification, ×180. E: Angiosarcoma (case 16), immunolocalization of VEGF. Magnification, ×325. F: Angiosarcoma (case 1). Immunolocalization of VEGF, Magnification, ×260. G: Control (case C1), negative immunostaining for p53. Magnification, ×180. H: Control (case C7), negative immunostaining for MDM-2. Magnification, ×180.

Cutoff Value for p53 Positivity

The p53 immunohistochemical cutoff values are not well established and are the subject of controversial discussion. In some investigations, cases have been considered to be immunoreactive irrespective of the number of stained cells, whereas in other studies different cutoff values have been used. 6 Most immunohistochemical studies on the p53 status of malignancies evaluated cases as p53-positive if they showed a nuclear immunoreaction in either more than 10% or more than 30% of the tumor cells. Against this background we chose as a cutoff value 40% of the cells with a staining intensity grade of at least intermediate, both in controls and sarcoma samples. Only cases above this cutoff value were considered to be p53-positive, ie, to show a definite p53 protein accumulation.

Cutoff Value for MDM-2 Positivity

Most studies using Southern blotting techniques demonstrated that MDM-2 protein overexpression was due to mdm-2 gene amplification. However, MDM-2 dysregulation has also been shown to be associated with transcriptional and/or translational deregulation. 11 Therefore, proof of an increased MDM-2 protein amount by immunohistochemistry should be the best way to reflect all these different ways of dysregulation. No definite cutoff values for the evaluation of immunohistochemical MDM-2 positivity have been established. Only tumors with an intermediate or stronger nuclear MDM-2 immunoreaction in more than 40% of the tumor cells were graded MDM-2-positive. This cutoff point is validated by the MDM-2 staining results of the benign control group, in which the number of MDM-2-positive endothelial cells and the MDM-2 staining intensity were clearly lower.

p53 Gene Sequence Analysis

Histopathological examination of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the tumors enabled us to select representative areas consisting predominantly of tumor from which DNA was extracted after microdissection. Ten 8-μm-thick paraffin sections were cut and placed into an Eppendorf tube using sterile toothpicks. The microtome was cleaned with xylene and the blade was exchanged for a new one before trimming the next case. Sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanol, and genomic DNA was purified according to a standard extraction method: tumor samples were digested with proteinase K (20 μg/ml; Sigma) in 200 μl digestion buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 50 mmol/L KCL; 1,5 mmol/L MgCL2; 0,5% Tween 20) at 55°C for 48 hours with constant shaking. DNA was extracted first with phenol/chloroform and then with chloroform/isoamylethanol. Cycle sequencing was performed according to standard protocols using dye-labeled terminators (ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit/AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, Applied Biosystems GmbH, Weiter-stadt, Germany) for performing enzymatic extension reactions and sets of PCR primers according to published sequences of exons 5–9 of the p53 gene (Table 3) ▶ . Automatic sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Table 3.

Primers for PCR Amplification of the p53 Gene (Exons 5–9)

| Exon | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequences | Product size (basepairs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | sense | 5′-CTGACTTTCAACTCTG-3′ | 253 |

| antisense | 5′-AGCCCTGTCGTCTCT-3′ | ||

| 6 | sense | 5′-CTCTGATTCCTCACTG-3′ | 166 |

| antisense | 5′-CCAGAGACCCCAGTTGCAAACC-3′ | ||

| 7 | sense | 5′-TGCTTGCCACAGGTCT-3′ | 210 |

| antisense | 5′-ACAGCAGGCCAGTGT-3′ | ||

| 8 | sense | 5′-AGGACCTGATTTCCTTAC-3′ | 245 |

| antisense | 5′-TCTGAGGCATAACTGC-3′ | ||

| 9 | sense | 5′-TATGCCTCAGATTCACT-3′ | 174 |

| antisense | 5′-TTGAGTGTTAGACTGGAAAC-3′ |

p53 Gene Analysis by DGGE Assay

For control and confirmation of the p53 gene sequence analysis a GC-clamped DGGE assay 34,35 of the p53 exons 5–8 was done according to Beck 36 (primers: exons 5–7; 36 exon 837).

Results

Detection of p53 Protein

The DO-7 antibody recognizes an epitope in the N terminus of the human p53 protein (amino acids 19 to 26), which is expressed on wild-type as well as on mutant p53 protein.

In ten of 19 angiosarcomas (53%) nuclear staining of p53 was observed in more than 40% of the total number of malignant endothelial cells. Staining intensity was intermediate or high in these cases (Table 1 ▶ , Figure 2, A and B ▶ ). In five sarcomas 30% of the tumor cells, and in four cases approximately 10% of the cells were positive. Cytoplasmic p53 staining was never observed. The grade of p53 positivity did not correlate with histological tumor grading, tumor localization, or the patient’s age (Table 1) ▶ .

Among the benign control lesions, nuclear p53 positivity graded intermediate in 50% of cells was observed in a hemangioma of infancy (case C6). One granulation tissue (case C3) exhibited an intermediate p53 staining reaction in 30% of the proliferating capillary endothelial cells, whereas in all other cases only a few (cases C2, C4, C5, C7) or no (cases C1, C8, C9, C10; Figure 2G ▶ ) p53-positive endothelial cells were observed (Table 2) ▶ .

Sequence Analysis of the p53 Gene

All angiosarcoma cases were investigated for p53 mutation in the hot spot regions of mutation (exons 5 to 9) using automatic DNA cycle sequencing. Cases 1 and 8 revealed missense mutations in the DNA-binding domain (codon 102 to 292) of the p53 gene.

Transversion was found in exon 6, codon 197 (GTG to GGG, case 1) and in exon 8, codon 274 (GTT to CTT, case 8). The observed mutations were tumor-specific because they were absent in DNA from normal cells of the patients.

The remaining 17 angiosarcoma cases exhibited p53 wild-type sequence.

DGGE Assay

The GC-clamped DGGE assay also revealed p53 mutation in cases 1 and 8. With this sensitive method no further p53 mutations were found in the angiosarcoma group. The DGGE assay clearly confirmed the data of the p53 sequence analysis.

Detection of MDM-2 Protein

In 13 of 19 angiosarcomas (68%) the number of MDM-2-positive tumor cells exceeded 40% of the total number of malignant cells. This grading was based on cells with clear nuclear intermediate or intense staining (Figure 2C) ▶ .

In four cases MDM-2 was positive in 30%, and in two cases in 10% of the malignant endothelial cells (Table 1) ▶ . In addition, a cytoplasmic MDM-2 immunoreaction was observed in five cases (cases 2, 5, 7, 11, and 16). In these cases nearly all tumor cells exhibited cytoplasmic staining (Figure 2D) ▶ .

Again, no correlation between MDM-2 staining and histological tumor grading, tumor localization, or the patient’s age was observed (Table 1) ▶ .

The benign control lesions revealed clearly lower levels of MDM-2 protein (Table 2) ▶ . Only in a capillary hemangioma (case C5) were 50% of the cells MDM-2-positive, but in this case staining intensity was very low. A hypertrophic granulation tissue (case C4) exhibited MDM-2 staining intensity graded intermediate in 30% of the proliferating endothelial cells. Either very faint MDM-2 immunoreaction in a few cells or no MDM-2 staining was observed in all other control cases. A cytoplasmic MDM-2 immunoreaction was not observed in the control group.

Detection of VEGF Protein

In 15 of 19 investigated angiosarcomas (79%) nearly all tumor cells (81–100%) revealed a uniform VEGF positivity. Staining intensity was either high (in 8 cases) or intermediate (in 7 cases) (Table 1 ▶ , Figure 2, E and F ▶ ). In three angiosarcomas 70% (case 13), 50% (case 14), and 30% (case 4) of the tumor cells were found to be positive for VEGF protein. One sarcoma (case 15) showed no VEGF staining. In these experiments no correlation between VEGF staining and, histological tumor grading, tumor localization, or the patient’s age was observed (Table 1) ▶ .

In the benign control group, high VEGF expression similar to that seen in the angiosarcomas was observed in a juvenile hemangioma (case C6). All other cases exhibited clearly lower numbers of positive cells and less intense staining (Table 2) ▶ .

Correlation between the Results

In 14 of 19 angiosarcoma cases comparably high numbers of both p53- and MDM-2-positive tumor cells were observed. In two tumors (cases 8 and 16) the number of p53-positive cells was twofold higher than that of MDM-2-positive cells, whereas in three angiosarcomas (cases 13, 14, and 19) the number of p53-positive tumor cells was clearly lower compared to the number of MDM-2-positive cells. All sarcomas with more than 40% p53-positive and/or MDM-2-positive cells were also clearly positive for VEGF. In three sarcomas (cases 5, 6, and 7) fewer cells expressed p53/MDM-2 than VEGF. Two angiosarcomas of the breast (cases 4 and 15) did not show increased p53 value or significant staining reaction for MDM-2 and VEGF. Both sarcomas with p53 mutation (cases 1 and 8) showed the highest levels of p53 and VEGF immunoreaction.

Overall, we demonstrated that in 74% (14/19) of the angiosarcomas investigated in this study the expression of p53, MDM-2, and VEGF is clearly increased in comparison to control tissues.

Discussion

Genomic mutation and aberrant expression of cell cycle regulators such as p53 represent key events in the development of neoplasia. Studies on the pathogenesis of angiosarcoma are scarce because of its rarity and the mechanisms active in the malignant transformation of endothelial cells are not well described. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to get basic knowledge of the status of important factors like p53, mdm-2, and VEGF gene products in angiosarcomas and their hypothetical involvement in regulating the growth of endothelial cells. We found a p53 protein accumulation in 53% (10/19) of the angiosarcomas. This percentage of p53 accumulation seems to fit in well with the recent data of Naka et al, whose molecular analysis of the p53 gene (exons 5–8) found 52% of angiosarcoma cases (17/33) to be mutated. 38 However, our collection revealed p53 gene missense mutations in only two cases (11%). Technical reasons for this difference were excluded by checking and confirming the results of sequence analysis by a highly sensitive DGGE assay. Although the investigated p53 exons 5–9 have been described as hot spots of mutations in numerous p53-related cancers, we cannot rule out the presence of additional mutations within the p53 sequence outside these exons. However, p53 mutations outside the hot spot areas are known to code for so-called nonsense proteins or unstable proteins, which are not detected by immunohistochemistry. Therefore, hypothetical mutations in these areas could not explain the increased accumulation of p53 protein in the remaining eight p53-positive angiosarcomas in our study. On the basis of these results, we investigated another mechanism which may influence p53 stability, ie, stabilization and inactivation of the p53 protein through the cellular p53 binding protein MDM-2. This mechanism is often found in soft tissue sarcomas but MDM-2 protein has so far not been investigated in angiosarcomas. Indeed, we detected a prominent nuclear MDM-2 immunoreaction in 68% of the angiosarcomas. Furthermore, a cytoplasmic MDM-2 immunoreaction was observed in 5 angiosarcomas, which may reflect a defective MDM-2 translocation pathway into the nucleus.

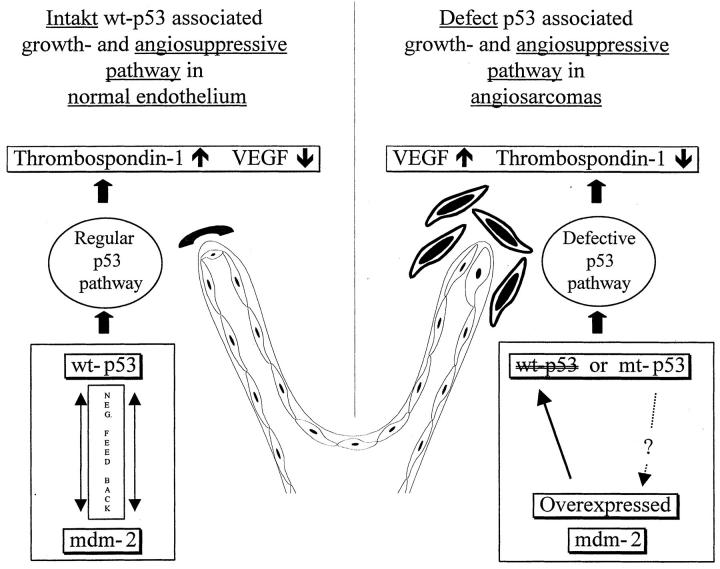

Based on studies of cultured human fibroblasts from cancer-prone Li-Fraumeni patients, Bouck and Dameron recently suggested a new function of wt-p53 in the regulation of angiogenesis. 39,40 They found that wt-p53 is a transcriptional activator of thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) expression. TSP-1 is present in normal resting endothelial cells and absent in actively forming endothelial cell sprouts and has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell migration and mitogenesis. In the presence of angiogenic stimuli TSP-1 maintains the differentiated, quiescent phenotype of endothelial cells and inhibits their conversion to a migratory, invasive phenotype. Induction of TSP-1 expression in transformed endothelial cells restores a normal phenotype and suppresses the tumorigenicity of the cells. 41-45 Wt-p53 not only activates the expression of the important antiangiogenic TSP-1 but also down-regulates the promoter activity of the strongly angiogenic VEGF in a dose-dependent manner. 17 Therefore, the observed deregulation of p53/MDM-2 expression may affect differentiation and phenotype of endothelial cells by modulation of the TSP-1/VEGF balance. The high expression of VEGF in our angiosarcomas and the clearly lower degree of p53, MDM-2, and VEGF immunoreaction in the benign control group supports this hypothesis (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 3.

The hypothetical role of the p53/MDM-2 pathway in normal endothelium and angiosarcoma development. Expression of wt-p53 is linked to the control of angiogenesis. wt-p53 positively regulates genes involved in intercellular signaling such as thrombospondin-1, a negative regulator of angiogenesis, and it exerts negative influence on VEGF gene expression. Abrogation of wt-p53 in endothelial cells either by functional inactivation through overexpression of mdm-2 protein or by p53 mutation obviously reflects the loss of an important cellular growth control and angiosuppressive pathway in angiosarcomas. Discontinuation of wt-p53 function leads to a decrease in Thrombospondin-1 production and a decline in the negative transcriptional control of VEGF. This shifts the net balance of positive and negative angiogenic factors to neovascularisation.

Only the hemangioma of infancy showed a strong VEGF immunoreaction. It is well known that in this entity VEGF expression is excessive during the proliferation phase but decreases toward normal levels during the involution phase. 46

Given the present state of knowledge about the pathogenesis of angiosarcomas, a correlative analysis aimed at prognostic or diagnostic factors was not a primary goal of our study. Investigation of very rare entities often cannot achieve reliable and confident statistical results because of small case numbers. Our angiosarcoma collection of 19 cases is one of the largest studied. However, an analysis of survival times correlated to our immunohistochemical results and matched with parameters like age and sex would need to be based on significantly higher case numbers to yield results with a high degree of confidence.

Taken together, the results of the present study show that more than two-thirds of the angiosarcomas analyzed exhibited a dysfunction of the p53/MDM-2 pathway, although there were several differences in tumor localization, histological tumor grading, age, and promotion events. A dysfunction of the p53/MDM-2 pathway may influence the development of angiosarcomas not just by effects on growth and apoptosis control but also by up-regulation of VEGF. Additional oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes certainly play a role in the genesis of malignant endothelial transformation, but our data suggest that functional impairment of the p53/MDM-2 pathway may be a key to the initiation and/or progression of a high percentage of angiosarcomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thelma Coutts (Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Germany) for linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. C. Zietz, Department of Pathology, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Thalkirchnerstr. 36, 80337 München, Federal Republic of Germany. E-mail: christian.zietz@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

This study contains parts of MR’s doctoral thesis.

References

- 1.Jaffe EA: Cell biology of endothelial cells. Hum Pathol 1987, 18:234-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denekamp J: Review article: angiogenesis, neovascular proliferation and vascular pathophysiology as targets for cancer therapy. Br J Radiol 1993, 66:181-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J: Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston: clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1757-1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malignant vascular tumors. In Soft Tissue Tumors. Edited by FM Enzinger and SW Weiss. Mosby, St. Louis. 1996, 641–677

- 5.Levine AJ: p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 1997, 88:323-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosari S, Viale G: The clinical significance of p53 aberrations in human tumours. Virchows Arch 1995, 427:229-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenblatt MS, Bennett WP, Hollstein M, Harris CC: Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene: clues to cancer etiology and molecular pathogenesis. Cancer Res 1994, 54:4855-4878 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beroud C, Verdier F, Soussi T: p53 gene mutation: software and database. Nucleic Acids Res 1996, 24:147-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollstein M, Shomer B, Greenblatt M, Soussi T, Hovig E, Montesano R, Harris CC: Somatic point mutations in the p53 gene of human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation. Nucleic Acids Res 1996, 24:141-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ: The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell 1992, 69:1237-1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Momand J, Zambetti GP: Mdm-2: “big brother” of p53. J Cell Biochem 1997, 64:343-352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliner JD, Kinzler KW, Meltzer PS, George DL, Vogelstein B: Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature 1992, 358:80-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leach FS, Tokino T, Meltzer P, Burrell M, Oliner JD, Smith S, Hill DE, Sidransky D, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: p53 Mutation and MDM2 amplification in human soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res 1993, 53:2231-2234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladanyi M, Cha C, Lewis R, Jhanwar SC, Huvos AG, Healey JH: MDM2 gene amplification in metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer Res 1993, 53:16-18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keleti J, Quezado MM, Abaza MM, Raffeld M, Tsokos M: The MDM2 oncoprotein is overexpressed in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines, and stabilizes wild-type p53 protein. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:143-151 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordon Cardo C, Latres E, Drobnjak M, Oliva MR, Pollack D, Woodruff JM, Marechal V, Chen J, Brennan MF, Levine AJ: Molecular abnormalities of mdm2 and p53 genes in adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res 1994, 54:794-799 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukhopadhyay D, Tsiokas L, Sukhatme VP: Wild-type p53 and v-Src exert opposing influences on human vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. Cancer Res 1995, 55:6161-6165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieser A, Weich HA, Brandner G, Marme D, Kolch W: Mutant p53 potentiates protein kinase C induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Oncogene 1994, 9:963-969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosai J, Carcangiu ML, DeLellis RA: Sarcomas. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of the Thyroid Gland. 1992, :259-265 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollstein M, Marion MJ, Lehman T, Welsh J, Harris CC, Martel Planche G, Kusters I, Montesano R: p53 mutations at A: T base pairs in angiosarcomas of vinyl chloride-exposed factory workers. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15:1-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trivers GE, Cawley HL, DeBenedetti VM, Hollstein M, Marion MJ, Bennett WP, Hoover ML, Prives CC, Tamburro CC, Harris CC: Anti-p53 antibodies in sera of workers occupationally exposed to vinyl chloride. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1400-1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soini Y, Welsh JA, Ishak KG, Bennett WP: p53 mutations in primary hepatic angiosarcomas not associated with vinyl chloride exposure. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16:2879-2881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen PR, Oberman HA: Angiosarcoma. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of Mammary Gland. 1993, :320-328 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen PR, Oberman HA: Postmastectomy angiosarcoma. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of Mammary Gland. 1993, :328-334 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nigro JM, Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, Hostetter R, Cleary K, Bigner SH, Davidson N, Baylin S, Devilee P, Glover T, Collins FS, Weston A, Modali R, Harris CC, Vogelstein B: Mutations in the p53 gene occur in diverse human tumour types. Nature 1989, 342:705-708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAllister HA, Fenoglio JJ: Angiosarcoma. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of the Thyroid Gland. 1978, :81-88 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke A, Virmandi R: Angiosarcoma. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of the Heart and Great Vessels. 1996, :136-140 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fechner RE, Mills SE: Angiosarcoma. Rosai J Sobin LH eds. Tumors of the Bones and Joints. 1993, :138-140 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeYong BR, Wick MR, Fitzgibbon JF: CD31: an immunospecific marker for endothelial differentiation in human neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem 1993, 1:97-100 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coindre JM, Trojani M, Contesso G, David M, Rouesse J, Bui NB, Bodaert A, DeMoscarel I, DeMoscarel A, Goussot JF: Reproducibility of a histopathologic grading system for adult soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer 1986, 58:306-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H: The use of antiavidin antibody and avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex in immunoperoxidase technics. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981, 75:816-821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H: Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 1981, 29:577-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remmele W, Hildebrand U, Hienz HA, Klein PJ, Vierbuchen M, Behnken LJ, Heicke B, Scheidt E: Comparative histological, histochemical, immunohistochemical and biochemical studies on oestrogen receptors, lectin receptors, and Barr bodies in human breast cancer. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1986, 409:127-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer SG, Lerman LS: Separation of random fragments of DNA according to properties of their sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1980, 77:4420-4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheffield VC, Cox DR, Lerman LS, Myers RM: Attachment of a 40-base-pair G + C-rich sequence (GC-clamp) to genomic DNA fragments by the polymerase chain reaction results in improved detection of single-base changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989, 86:232-236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck JS, Kwitek AE, Cogen PH, Metzger AK, Duyk GM, Sheffield VC: A denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis assay for sensitive detection of p53 mutations. Hum Genet 1993, 91:25-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borresen AL, Hovig E, Smith Sorensen B, Malkin D, Lystad S, Andersen TI, Nesland JM, Isselbacher KJ, Friend SH: Constant denaturant gel electrophoresis as a rapid screening technique for p53 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991, 88:8405-8409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naka N, Tomita Y, Nakanishi H, Araki N, Hongyo T, Ochi T, Aozasa K: Mutations of p53 tumor-suppressor gene in angiosarcoma. Int J Cancer 1997, 71:952-955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dameron KM, Volpert OV, Tainsky MA, Bouck N: Control of angiogenesis in fibroblasts by p53 regulation of thrombospondin-1. Science 1994, 265:1582-1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dameron KM, Volpert OV, Tainsky MA, Bouck N: The p53 tumor suppressor gene inhibits angiogenesis by stimulating the production of thrombospondin. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1994, 59:483-489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed MJ, Iruela Arispe L, O’Brien ER, Truong T, LaBell T, Bornstein P, Sage EH: Expression of thrombospondins by endothelial cells. Injury is correlated with TSP-1. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:1068-1080 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bornstein P, Sage EH: Thrombospondins. Methods Enzymol 1994, 245:62-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheibani N, Frazier WA: Thrombospondin 1 expression in transformed endothelial cells restores a normal phenotype, and sup-presses their tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:6788-6792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Good DJ, Polverini PJ, Rastinejad F, Le Beau MM, Lemons RS, Frazier WA, Bouck NP: A tumor suppressor-dependent inhibitor of angiogenesis is immunologically and functionally indistinguishable from a fragment of thrombospondin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:6624-6628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawler J: The structural and functional properties of thrombospondin. Blood 1986, 67:1197-1209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi K, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Rogers RA, Folkman J, Ezekowitz RA: Cellular markers that distinguish the phases of hemangioma during infancy and childhood. J Clin Invest 1994, 93:2357-2364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]