Abstract

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) is a critical structure involved in coordinating autonomic and visceral activities. Previous independent studies have demonstrated efferent projections from the NTS to the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi) and the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) in rat brain. To further characterize the neural circuitry originating from the NTS with postsynaptic targets in the amygdala and medullary autonomic targets, distinct green or red fluorescent latex microspheres were injected into the PGi and the CNA, respectively, of the same rat. Thirty-micron thick tissue sections through the lower brainstem and forebrain were collected. Every fourth section through the NTS region was processed for immunocytochemical detection of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of catecholaminergic neurons. Retrogradely labeled neurons from the PGi or CNA were distributed throughout the rostro-caudal segments of the NTS. However, the majority of neurons containing both retrograde tracers were distributed within the caudal third of the NTS. Cell counts revealed that approximately 27% of neurons projecting to the CNA in the NTS sent collateralized projections to the PGi while approximately 16% of neurons projecting to the PGi sent collateralized projections to the CNA. Interestingly, more than half of the PGi and CNA projecting neurons in the NTS expressed TH immunoreactivity. These data indicate that catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS are poised to simultaneously coordinate activities in limbic and medullary autonomic brain regions.

Keywords: collateralized projections, immunocytochemistry, retrograde tracing, tyrosine hydroxylase

1. Introduction

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), located in the dorsomedial medulla, is a critical structure involved in many autonomic functions including cardiovascular- and respiratory-related activities (Ross et al., 1981; Sessle and Henry, 1985; Allen and Cechetto, 1992). Afferent synaptic input to the NTS arises from primary afferent fibers that innervate the tongue (Hamilton and Norgren, 1984) and visceral fibers of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves that serve various modalities including baroreceptor and chemoreceptor functions (Altschuler et al., 1989; Ciriello et al., 1994). As such, these afferent inputs have been implicated in the regulation of cardiovascular, respiratory and general visceral activities. NTS neurons are known to contain neurochemically distinct types of neurons expressing both neuropeptides and neurotransmitters (Herbert and Saper, 1990; Riche et al., 1990; Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990, 1995) A major subset of neurons in the NTS contain catecholamines, including noradrenaline and adrenaline (Hokfelt et al., 1984; Kalia et al., 1985). Specifically, the catecholamine-containing neurons of the A2 noradrenergic group are primarily distributed within the medial division of the NTS. Previous investigations have implicated catecholamine neurons originating from the NTS in the regulation of autonomic functions (Murphy et al., 1994; Chan and Sawchenko, 1995, 1998; Buller et al., 1999). Therefore, the NTS serves as a vital relay center for integration of various yet related autonomic functions.

Previous anatomical tracing studies using wheat germ agglutinin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase coupled to gold (WGA-Au-HRP) have provided evidence for efferent projections from the NTS to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA; Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Riche et al., 1990; Jia et al., 1997). Likewise, using the same retrograde tracer, a projection from the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi) to the NTS was established (Ross et al., 1985; Hancock, 1988; Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Mtui et al., 1995; Aicher et al., 1996). The term PGi has been used in a myriad of anatomical and physiological studies (Satoh et al., 1979; Punnen et al., 1984; Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Nevertheless, PGi is a larger anatomical region that includes the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the autonomic literature (Dampney and Moon, 1980; Ross et al., 1981; Dampney et al., 1982; Ross et al., 1984; Ross et al., 1985; McAllen, 1986). Thus, many studies use these terms interchangeably. In our present study, we chose to use the term PGi consistent with our previous anatomical reports on this region (Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a).

Few studies have sought to examine whether individual NTS neurons send collateralized projections to the PGi and the CNA as its medullary and amygdalar autonomic targets. Retrograde tracing studies in combination with immunohistochemistry have shown that CNA-projecting neurons from the NTS express tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity (Riche et al., 1990; Jia et al., 1997). Moreover, recent evidence showed that very few PGi-projecting neurons in the NTS are catecholaminergic.

A host of anatomical and physiological studies have shown that the PGi and CNA both participate in cardiovascular (Ross et al., 1984; Maskati and Zbroayma, 1989), respiratory (Harper et al., 1984; McAllen, 1986), nociceptive (Satoh et al., 1979; Punnen et al., 1984), and neuroendocrine (Price et al., 1987) functions. Hence, such coordinated circuitry is important in elucidating the regulation of post-synaptic targets by NTS neurons. Therefore, in the present study, using restricted injections of distinct fluorescent latex microspheres into the PGi and the CNA, we examined possible collateralized projections of the NTS to medullary and amygdalar targets. To further examine the neurochemical phenotype of the collateralized projections from the NTS to the PGi and the CNA, we examined whether NTS-projecting neurons to the PGi and the CNA contain TH, a marker of catecholaminergic neurons.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Twenty one adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–280g; Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were used in the present study. Animals were housed two to three per cage in a controlled environment (12-h light schedule, temperature at 20 ºC). Food and water were provided ad libitum. The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University and were conducted in accordance with NIH guide for care and use of laboratory animals. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used.

2.2 Fluorescent latex microspheres injections into PGI and CNA

All animals were injected with fluorescent latex microspheres (Lumafluor Corp., Naples, FL) into both PGi and CNA. Animals were initially anesthetized with a combination of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (2mg/kg) in saline and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus for surgery. Anesthesia was supplemented with isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL; 0.5–1.0%, in air) via a specialized nose cone affixed to the sterotaxic frame (Stoelting Corp., Wood Dale, IL). The temperature of the animal was monitored throughout the surgical procedure and kept at 37 °C by using a feedback-controlled heating device.

Micropipettes (Kwik-Fil, 1.2 mm outer diameter; World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL) with tip diameters of 20–25 μm were filled with green or red fluorescent latex microspheres. The tips of the micropipettes were placed at the following coordinates for the PGi, 3.5 mm posterior from lambda, 1.7 mm medial/lateral, 8.5 mm ventral from the top of the skull, and the CNA, 2.8 mm posterior from bregma, 4.5 mm medial/lateral and 8 mm ventral from the top of the skull. The stereotaxic coordinates of the injection sites were based on the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986). Green or red fluorescent latex microspheres were injected using a Picospritzer (General Valve Corporation, Fairfield, NJ) at 24–26 psi and over a 10 min period. Pipettes were left at the site of injections for 5 min after tracer deposit. Twenty one rats were injected with green and red fluorescent latex microspheres into the PGi and the CNA, respectively. Tracer injections were also reversed in eight rats to ensure that patterns of transport were similar between tracers. Following surgery, animals were housed individually and had free access to food and water.

2.3 Perfusion and immunocytochemistry

After a survival period of 5 days, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60mg/kg; Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Deerfield, IL) intraperitoneally and transcardially perfused with 50 ml of heparinized saline followed by 400 ml of 4% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). The brains were removed, blocked, immersed in 4% formaldehyde overnight at 4°C, and stored in 30% sucrose solution in 0.1 M PB containing 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C for few days. The side of the brain contralateral to the injection was notched to verify tissue orientation following sectioning. The whole rat brain was frozen using Tissue Freezing Medium (Triangle Biomedical Science, Durham, NC). Frozen 30 μm-thick sections were cut in the coronal plane using a freezing microtome (Micron HM550 cryostat; Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and collected in 0.1 M PB. Subsequently, every fourth section through the rostro-caudal extent of the PGi and the CNA was mounted on gelatinized coated slides, allowed to dry and coverslipped using Krystalon mounting medium (EM Industries, Gibbstown, NJ) and stored in complete darkness at 4°C.

Every fourth section through the rostro-caudal segment of the NTS was processed for immunocytochemical visualization of TH-immunoreactivity. Free-floating sections were rinsed extensively in 0.1 M PB followed by rinses in 0.1 M tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.6). Sections were then incubated in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.1M TBS for 30 min, and rinsed in 0.1 M TBS for 10 min, three times. Following rinses, the sections were incubated overnight in a mouse monoclonal antibody for TH (1:1,000; Immunostar Inc., Hudson, WI) in 0.1% BSA and 0.25% Triton X-100 in 0.1M TBS. Incubation time was 15–18 h in a rotary shaker at room temperature. The specificity of the mouse antiserum against TH was previously described (Van Bockstaele and Pickel, 1993). Sections were rinsed extensively in 0.1M TBS followed by incubation in a secondary antibody of cyanine dye Cy5 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Westgrove, PA) in 0.1% BSA and 0.25% Triton X-100 in 0.1M TBS for 2 h. Following extensive rinses in 0.1 M TBS, sections were mounted on gelatinized coated slides, allowed to dry and coverslipped using Krystalon and stored in complete darkness at 4°C. A confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) was used to visualize the immunofluorescence labeling and digital images were obtained and imported using the LSM 5 image browser (Carl Zeiss Inc.). Figures were assembled and adjusted for brightness and contrast in Adobe Photoshop.

2.4 Data analysis

Coronal sections through the PGi and the CNA were examined for accurate injections of the fluorescent latex microspheres. Only animals with satisfactory injection sites were utilized for data analysis. The criteria for defining satisfactory injection sites included the extent of diffusion of injections, proximity of injections to the target nucleus and retrograde labeling in the NTS. For the injection sites, criteria were evaluated by obtaining the bright field and immunofluorescence images of injection sites (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan). Images were then captured using Spot Advanced software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Retrograde labeling in the NTS was evaluated by obtaining the immunofluorescence images. Cases with injections centered and localized for both the PGi and the CNA were included in the analysis. Thus, only four rats were used for quantification and data analysis.

As described for the rat brain (Norgren, 1978), the NTS is approximately 4.0 mm in its caudal to rostral dimension, extending from the caudal pons throughout the rostral and caudal medulla. Specifically, the NTS extends from the anterior portion of the external cuneate nucleus to the posterior portion of the nucleus gracilis. Sections through the rostro-caudal segment of the NTS were systematically categorized into two subregions as rostral and caudal, for the purpose of the analysis. The subregions correspond to the coordinates represented in the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The rostral NTS was defined as the region rostral to the area postrema, at a level where the medial border of the NTS had drawn away from the fourth ventricle, approximately −12.8 mm from bregma (Hermes et al., 2006). The caudal NTS was defined as the area immediately caudal to the area postrema centered at approximately −14.3 from bregma through the middle of the rostro-caudal extent of the area postrema, centered at approximately −13.8 mm from bregma. The caudal NTS in the present study extended from the commissural NTS and subpostremal NTS as defined in the study of Hermes et al., 2006 (Hermes et al., 2006).

As the majority of neurons containing both retrograde tracers were concentrated in the caudal subregion of the NTS, the data presented in this study were focused on the caudal subregion of the NTS, specifically at the level around the area postrema and caudal to it. Retrogradely labeled neurons showing single and dual fluorescent latex microspheres were counted in each section (120 μm intervals) according to their rostro-caudal distribution. Cell counts included only tissues taken immediately caudal to the area postrema and contained commissural nuclei, centered at approximately −14.30 mm from bregma, through the middle of the rostrocaudal extent of the area postrema, centered at approximately −13.80 mm from bregma. This resulted in 8 sections per animal. Cell counts were then taken and were represented as mean ± SEM of the numbers of cells found per animal across each series of injections.

3. Results

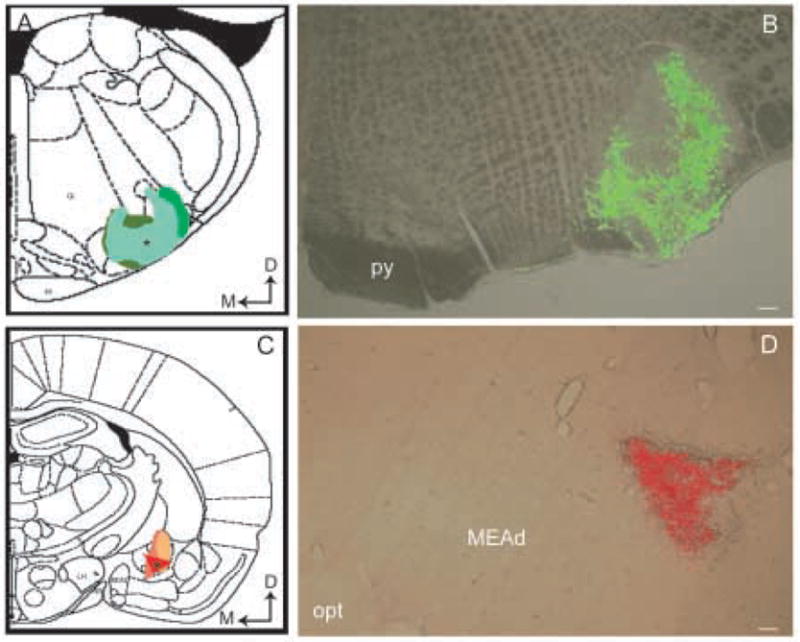

Figure 1 shows representative injections of tracers into the PGi and the CNA that were effective in producing retrograde labeling in the NTS. These injections optimally filled the PGi and the CNA, respectively, throughout their rostral and caudal extent and did not significantly diffuse outside PGi and the CNA regions. The fluorescent latex microsphere injections were centered in the PGi (Fig. 1B) and the CNA (Fig. 1D) at anterior posterior levels that corresponded to Plates 60 (PGi) and 26 (CNA), respectively, of the brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Also shown on Figure 1 are composite figures of injection sites of the fluorescent latex microspheres in the PGi (Fig. 1A) and the CNA (Fig. 1C) from three other cases. The injections in the CNA extended into the medial and lateral parts of the nucleus (Fig. 1C). The lateral part included capsular and central subdivisions. In two rats (R22 and R6), the tracer spread ventrally and involved a small part of the adjacent intercalated amygdaloid nucleus (Fig. 1C). The minimal involvement of the neighboring amygdaloid structure did not result in a different number of retrogradely labeled neurons in the NTS (Fig. 4C). The injections in the PGi were centered in the lateral division of PGi (Fig. 1A). In two cases (R2, R22) there was a limited diffusion from the injection sites, however, the dense core of fluorescent latex microsphere injections was still centered within the PGi. Four cases yielded optimal retrograde labeling in the NTS (Fig. 2A). It was noted that small and highly localized injections of fluorescent latex microspheres (Fig. 1B) yielded an effective retrograde transport (Figs. 2A–B, 3A–B) confirming Katz and colleagues’ (Katz et al., 1984; Katz and Iarovici, 1990) description of using retrograde beads in tracing studies. Reversal of tracers placed into the PGi and the CNA yielded no appreciable difference in the observed distribution of retrogradely labeled neurons in the NTS.

Figure 1.

Low-power magnification images of merged brightfield and immunofluorescence photomicrographs showing representative injections of green (B) and red (D) fluorescent latex microspheres into the PGi and the CNA, respectively, in rat brain. Schematic diagrams adapted from the rat brain atlas of Swanson (61) showing the anterior posterior level of the representative injection sites in the PGi (A) and the CNA (C). Asterisks in panels A and C show the injection sites presented in panels B and D, respectively. Arrows indicate dorsal (D) and medial (M) orientation of the sections. Gi, gigantocellular reticular nucleus; IA, intercalated nuclei amygdala; LH, lateral hypothalamic area; MEAd, medial nucleus amygdala, anterodorsal part; opt, optic tract; py, pyramidal tract. Scale bar, 100 μm.

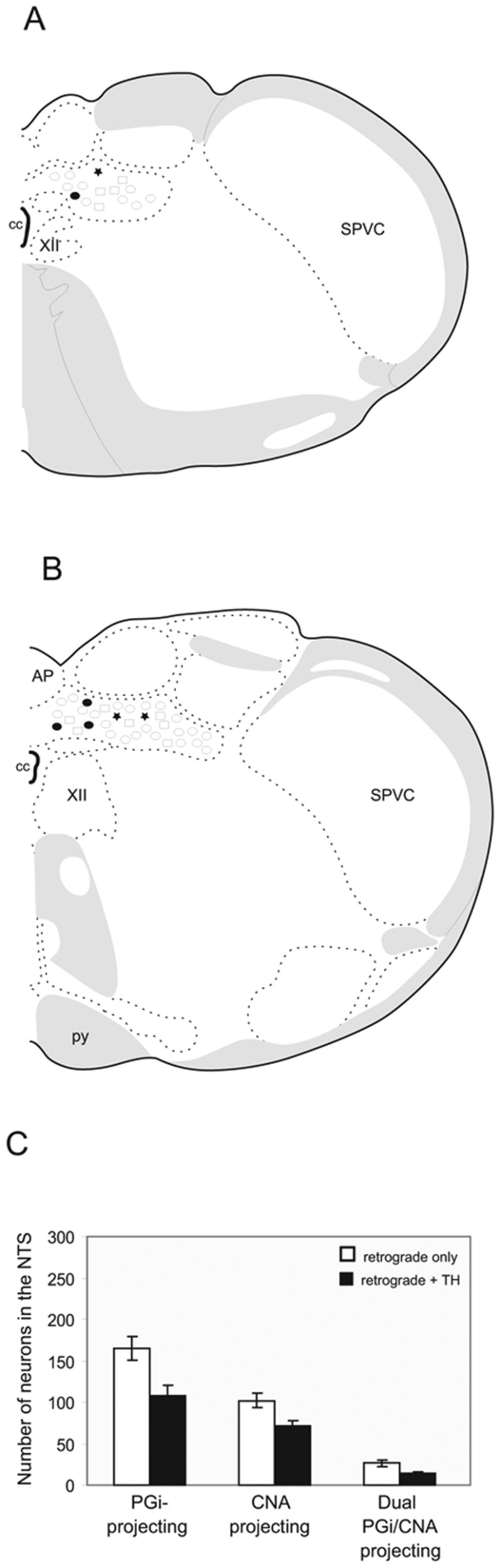

Figure 4.

A–B. Schematic drawings of two representative levels of the NTS showing location of retrogradely labeled neurons from the PGi (open circles) and the CNA (squares). Dual labeled neurons with and without tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactivity are illustrated as stars and filled circles, respectively. AP, area postrema; cc,central canal; py, pyramidal tract; pyd, pyramidal decussation; SPVC, spinal nucleus of trigeminal (caudal part); SPVI, spinal nucleus of trigeminal (interpolar part); XII, hypoglossal nucleus. C. Bar graph showing the number of singly and dual retrogradely labeled neurons in the NTS from the PGi and the CNA with (black) or without (white) tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-immunoreactivity. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

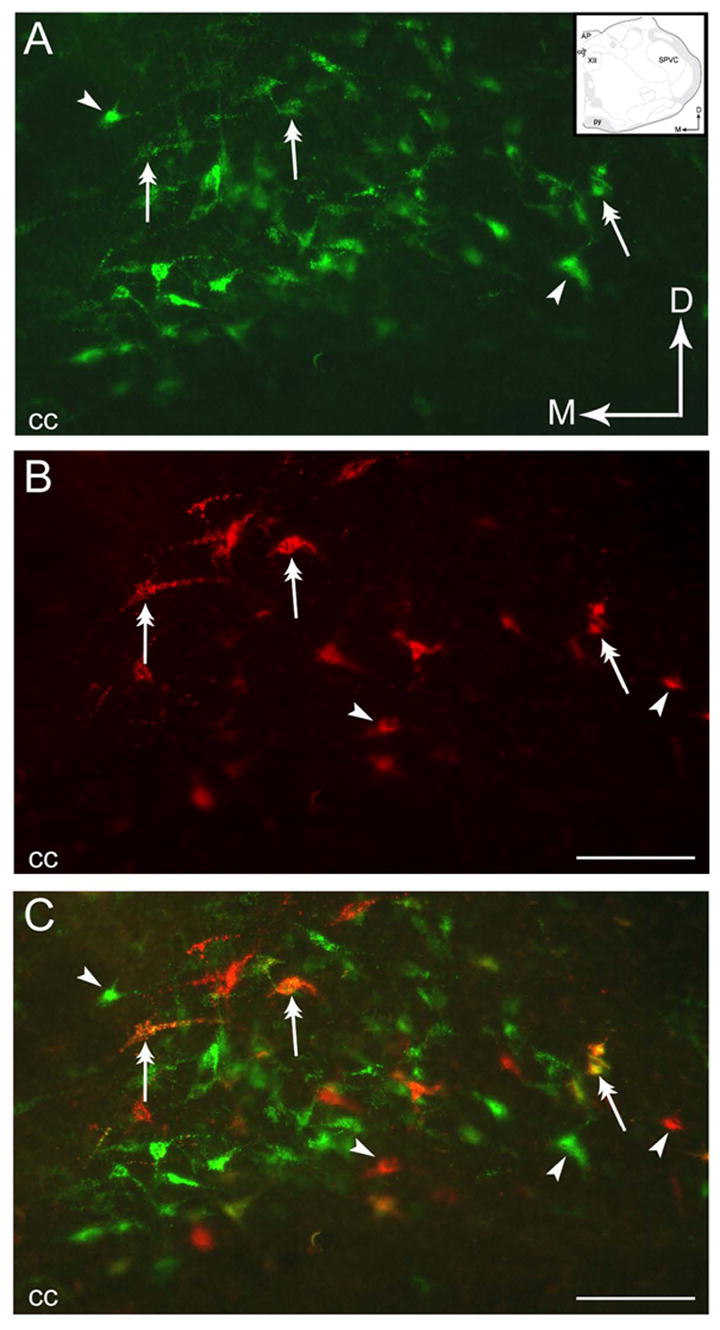

Figure 2.

Neurons within the NTS send collateralized projections to the PGi and the CNA. A–B. Photomicrographs of a coronal section through the NTS showing retrogradely labeled neurons from the PGi as detected using green fluorescent latex microspheres(A) and from the CNA using red fluorescent latex microspheres (B). Arrows indicate dorsal (D) and medial (M) orientation of the section. Inset shows a schematic illustration of the region shown in panels A–C adapted from the rat brain atlas of Swanson (1992). C. Merged image of panels A and B showing dual labeled neurons (double-headed arrows) and singly labeled neurons (arrowheads). AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; py, pyramidal tract; SPVC, spinal nucleus of the t rigeminal tract (caudal part); XII, hypoglossal nucleus. Scale bar, 100 μm.

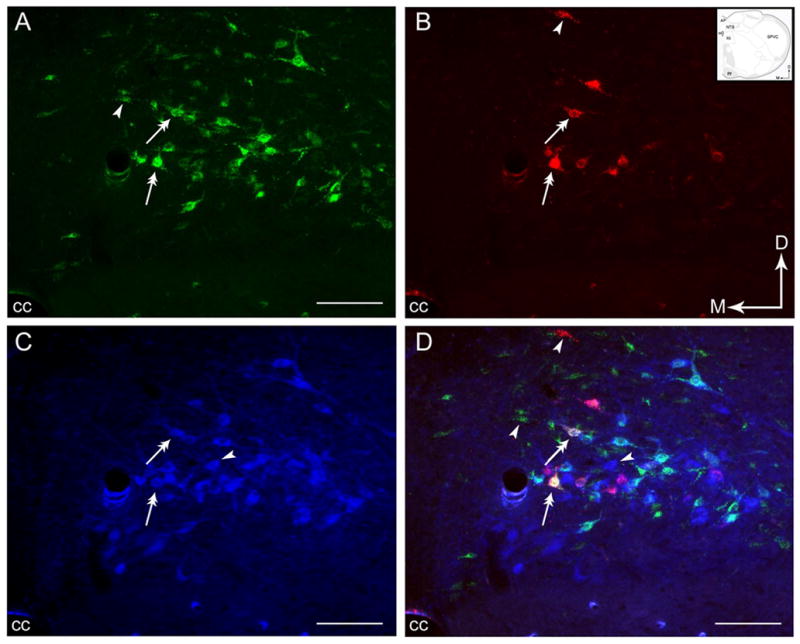

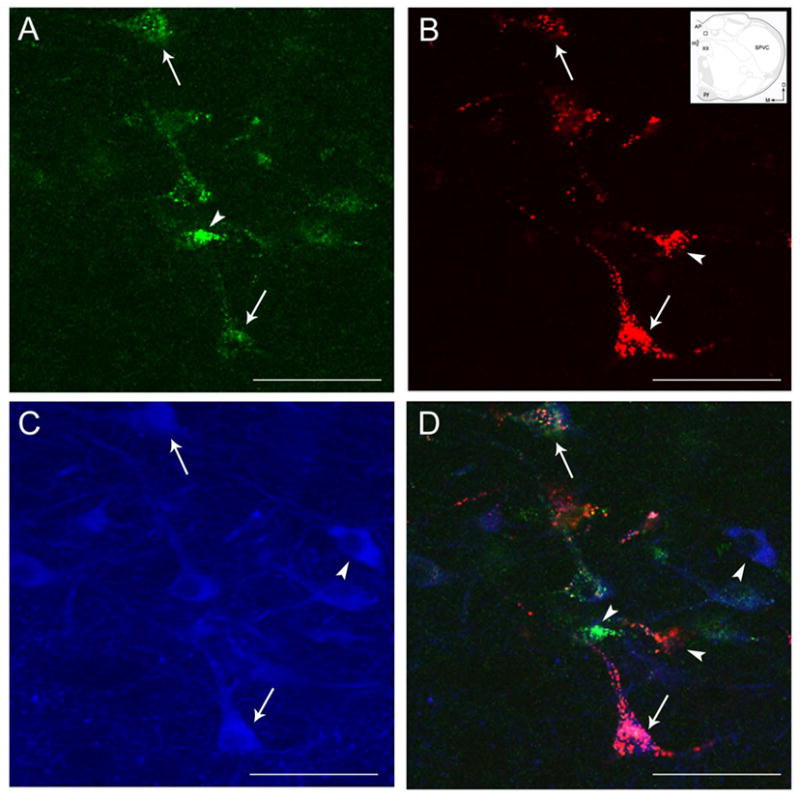

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs showing the distribution of retrogradely labeled neurons from the PGi and the CNA with respect to catecholaminergic neurons. A–C. Distribution of neurons projecting to the PGi (A), the CNA (B), and neurons immunoreactive to TH (C) in the NTS. D. Merged image of panels A, B and C showing singly labeled neurons (arrowheads) and dual-labeled neurons (double-headed arrows). Arrows indicate dorsal (D) and medial (M) orientation of the sections. Inset shows a schematic illustration of the region shown in panels A–D adapted from the rat brain atlas of Swanson (1992). AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; py, pyramidal tract; SPVC, spinal nucleus of the trigeminal tract (caudal part); hypoglossal nucleus. Scale bar = 100 μm.

3.1 Nucleus paragigantocellularis-projecting neurons

With tracer injections restricted to the PGi (Fig. 1B), the most frequent location of retrogradely labeled neurons was the caudal level of the NTS (Fig. 2A). The caudal level of the NTS extends from the area ventrolateral to the median accessory nucleus of the medulla up to the rostral region of the cuneate nucleus. Very few retrogradely labeled neurons were observed in the rostral NTS. Most frequently, the retrogradely labeled neurons were found ipsilateral to the side where the tracer was injected.

3.2 Central nucleus of the amygdala-projecting neurons

With tracer injections restricted to the CNA (Fig. 1D), however, the most numerous retrogradely labeled perikarya were distributed at the caudal level of the NTS (Fig. 2B). Retrogradely labeled perikarya were particularly numerous ventral to the area postrema and were observed specifically in the nucleus commisuralis and medial nucleus of the NTS. Unlike PGi-projecting neurons, CNA-projecting neurons were fewer in number (Fig. 3D). The retrogradely labeled neurons were distributed ipsilaterally whereas very few retrogradely labeled neurons were noted contralateral to the injection site.

3.3 Dual-retrogradely labeled neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract

Injections of the tracer into the PGi and the CNA yielded retrogradely labeled neurons throughout the rostro-caudal portion of the NTS (Fig. 2C). However, the majority of dual-retrogradely labeled neurons were distributed in the caudal NTS. These dual-retrogradely labeled neurons were found at the level of the obex and area postrema. However, dual-retrogradely labeled neurons were more numerous at the level of the area postrema, dorsal and lateral to the central canal (Fig. 4A–B). Very few dual-retrogradely labeled neurons were located in the medial nucleus of the NTS and almost none in the rostral NTS. The distribution of the neurons singly and doubly labeled in the caudal NTS is depicted in Figs. 4A and 4B.

No collateralized projections were found in the rostral level of the NTS or the medial, gelatinous and lateral nuclei of the caudal NTS. Hence, anterior to the level −13.24 from bregma, there were rarely dual retrogradely labeled neurons observed.

Quantitative analysis revealed that 16% of the PGi-projecting neurons send collaterals to the CNA, whereas, 27% of the CNA-projecting neurons send collaterals to the PGi (Fig. 4C). Evidently, although there were more retrogradely labeled neurons in the NTS that project to the PGi compared to those that project to the CNA, the percentage of CNA-projecting neurons that send collaterals to the PGi was higher.

3.4 Dual-retrogradely labeled neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract are catecholaminergic

Using triple-fluorescence labeling, one half of cells (55%) that contained both retrograde tracers also expressed TH-immunoreactivity (Figs. 3D and 5D). Many of the triple-labeled neurons were fusiform in shape (Figs. 3A–B, 3D, 5A–B and 5D). The majority of the neurons that send collateralized projections to the PGi and the CNA and expressed TH immunoreactivity were found predominantly in caudal NTS. These triple-labeled neurons were concentrated mainly at the level of the obex and area postrema, particulary in the nucleus commisuralis of the NTS and, dorsal and medio-lateral to the central canal. In regions rostral to the area postrema, although there were occasional dual-retrogradely labeled neurons, none of them were observed to express TH immunoreactivity.

Figure 5.

High magnification photomicrographs of coronal sections through the caudal NTS showing retrogradely labeled neurons from the PGi (A), the CNA (B), and TH-immunoreactive neurons (C). Merged image (D). Inset in B is adapted from the rat brain atlas of Swanson (1992) showing a low magnification schematic diagram of the region shown in panels A–D. Arrows in the inset indicate dorsal (D) and medial (M) orientation of the sections. Arrowheads point to singly labeled neurons while arrows indicate dual-retrogradely labeled neurons expressing TH-immunoreactivity. cc, central canal. Scale bar = 250 μm.

A large number of TH-labeled neurons projecting to either the PGi or the CNA (Fig. 3D) were noted. Approximately 65% (108 out of 165) of NTS neurons projecting to the PGi and 70% (71 out of 102) of NTS neurons projecting to the CNA expressed TH-immunoreactivity (Fig. 4C).

4. Discussion

The present results confirm previous independent anatomical studies demonstrating projections from the NTS to the PGi and the CNA. Our data also provide evidence that the NTS neurons innervate the autonomic medullary and amygdalar targets via collateralized projections to the PGi and the CNA. Our findings indicate that approximately 16% of the PGi projecting neurons from the NTS send collaterals to the CNA and that approximately 27% of the CNA projecting neurons from the NTS send collaterals to the PGi. More interestingly, more than half of those neurons that send collaterals to the PGi and the CNA are catecholaminergic. Additionally, our results provide the first evidence that PGi-projecting neurons in the NTS are catecholaminergic.

Our discrete injection placements in this study yielded retrograde labeling in the NTS that reflects afferent input to the NTS from the PGi and the CNA. The retrograde labeling is not likely due to significant uptake of tracer from the areas adjacent to the injection sites for the following reasons: 1) injections centered in the PGi and the CNA that were used in the analysis did not significantly encroach on neighboring nuclei ; 2) independent anterograde and retrograde tracing studies (Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Riche et al., 1990; Roder and Ciriello, 1993; Jia et al., 1997) support projections from the PGi and CNA; and 3) the retrogradely labeled neurons within the dorsal medulla was comparable to the anatomical distribution previously described in other studies (Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Jia et al., 1997).

The retrogradely labeled neurons in the NTS that send collaterals to the PGi and the CNA are concentrated in the caudal NTS, occupying the commissural portion and A2 region of the NTS. This location confirms the position of the retrogradely labeled cells in the NTS that project to the PGi and the CNA reported in previous tracing studies (Van Bockstaele et al., 1989; Riche et al., 1990; Roder and Ciriello, 1993; Jia et al., 1997). Therefore, activity in a subset of NTS neurons that project to the PGi will concomitantly activate the CNA and activity of a portion of the NTS neurons that influences the CNA will impact upon the PGi in a parallel manner. The NTS has long been known to be involved in autonomic functions (Ross et al., 1981; Sessle and Henry, 1985; Altschuler et al., 1989; Allen and Cechetto, 1992; Ciriello et al., 1994). Neurons in the NTS serve as the principal relay of afferent inputs from various information including baroreceptor, chemoreceptor, cardiopulmonary, cardiovascular and visceral afferents (Palkovits and Zaborszky, 1977; Hancock, 1988; Ciriello et al., 1994; Grigson et al., 1997b; Shimura et al., 1997). Hence, the NTS is the primary site where various distinct but related functions intersect for the integration of autonomic outputs. The present findings further extend our knowledge of autonomic regulation by showing that the NTS simultaneously coordinates autonomic information to the PGi and the CNA, brain regions that are similarly engaged in autonomic functions (Satoh et al., 1979; Kapp et al., 1982; Harper et al., 1984; Punnen et al., 1984; McAllen, 1986; Price et al., 1987; Maskati and Zbroayma, 1989; Grigson et al., 1997b).

Interestingly, more than half of the neurons within the NTS send catecholaminergic bifurcating neurons to the PGi and the CNA. This indicates that the catecholamine in the PGi and the CNA is one of the major transmitters involved in the pathway arising from the NTS. This result further establishes that the catecholaminergic projections from the medulla to the CNA originate from the A2 cell group, and confirm previous anatomical tracing studies demonstrating that the A1 and A2 cell groups provide the bulk of catecholaminergic input to the CNA (Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990, 1995; Jia et al., 1997) Specifically, the CNA-projecting neurons in the NTS were TH and phenylethanolamine-N-methlytransferase (PNMT) immunoreactive (Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990, 1995; Jia et al., 1997). As such, 60–80% of TH-immunoreactive neurons (Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990; Grigson et al., 1997a; Jia et al., 1997) and 9% of PNMT-immunoreactive neurons (Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990) in the NTS projected to the CNA. In retrograde tracing studies, we have shown that the NTS provides afferent input to the PGi (Van Bockstaele et al., 1989). However, recent anatomical studies combining immunohistochemistry and retrograde tracing have shown that majority of NTS neurons project to only one autonomic target, and that the catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS do not send collateral projections to multiple targets (Hermes et al., 2006). The discrepancy between these results and our present findings may be attributed to the difference in the selection of injection targets. While their dual retrograde tracer microinjections (Hermes et al., 2006) were made into pairs of targets namely: paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and parabrachial nucleus or caudal ventrolateral medulla; and parabrachial nucleus and caudal ventrolateral medulla, we injected fluorescent latex microspheres into the CNA and ventrolateral medulla or the PGi. Whereas, the CNA is located in the limbic region, the paraventricular nucleus and parabrachial nucleus are located in hypothalamic and pontine regions, respectively. Moreover, in the present study, the placement of fluorescent latex microspheres in the PGi was injected at 3.5 mm posterior from lambda, 1.7 mm medial/lateral, 8.5 mm ventral from the top of the skull. This is the area immediately rostral to the area postrema while their injection site in the caudal ventrolateral medulla was made at the level of the area postrema specifically 1.0 mm anterior, 2.0 mm lateral and 2.0 mm ventral from the calamus scriptorius (Hermes et al., 2006). These could possibly explain the many catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS that project to both the PGi and the CNA in the present study. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the NTS neurons projecting to the caudal ventrolateral medulla are non-catecholaminergic (20) and probably glutamatergic (58) in light of our findings showing that NTS neurons projecting to the rostral ventrolateral medulla (or PGi) are catecholaminergic. It is thought that the projections from the NTS to caudal ventrolateral medulla are baroreceptive while NTS projections to rostral ventrolateral medulla (or PGi) are chemoreceptive. However, it has never been determined whether different groups of NTS neurons project to these functionally distinct regions in the medulla. Our study and the Hermes study (20) suggest that two pathways may exist. Specifically, one subset of NTS neurons projecting to the caudal ventrolateral medulla may be non-catecholaminergic and probably glutamatergic while NTS neurons projecting to the rostral ventrolateral medulla or the PGi may be catecholaminergic. Further anatomical and physiological investigations are needed to clarify this issue.

NTS neurons are known to sense peripheral signals related to epinephrine elevations resulting in a heightened physiological state in response to emotionally arousing events (Miyashita and Williams, 2003, 2004). This information is then conveyed via NTS neurons to brainstem and limbic regions that are engaged in memory storage (Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Intra-NTS infusion of a memory-enhancing dose of epinephrine has been shown to increase norepinephrine levels in the amygdala (Clayton and Williams, 2000). Similarly, electrical stimulation of the NTS excites PGi neurons (Lovick, 1988) that are known to provide afferent inputs to the locus coeruleus (Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a) resulting in widespread norepinephrine release in cortical areas. In light of the present findings, it is tempting to speculate that during emotionally arousing events or following stress, NTS neurons that collateralize to the PGi and the CNA are poised to co-regulate limbic regions (CNA) and widespread cortical areas via projections from the PGi to the LC.

Electrophysiological studies demonstrate that electrical stimulation of neurons in the CNA causes an increase in heart rate and mean arterial pressure (Galeno and Brody, 1983; Grigson et al., 1997a). Similarly, electrical stimulation, glutamate microinjection or kainic acid application to the PGi elicits increases in arterial pressure (Dampney et al., 1982; McAllen et al., 1982; Grigson et al., 1997a). Conversely, bilateral lesions of the CNA in spontaneous hypertensive rats attenuate the development of hypertension (Galeno et al., 1982). Likewise, bilateral electrolytic lesions or local cooling to the PGi leads to a remarkable lowering of arterial pressure (McAllen et al., 1982; Grigson et al., 1997a) Studies on the rat models of experimental hypertension have shown evident alterations in catecholamine concentrations in the medulla oblongata and hypothalamus (Versteeg et al., 1976; Wijnen et al., 1978). Catecholamines have been implicated in the increases in the heart rate and arterial pressure (Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990). Thus, the dual catecholaminergic innervation from the NTS to the CNA and the PGi may coordinate responses to hypertensive events occurring during stress. Furthermore, catecholamines are known to influence the activity of neurons in the brain including the PGi and the CNA (Clayton and Williams, 2000; Williams et al., 2000). The PGi and CNA are enriched with corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) synthesizing neurons (Swanson et al., 1983; Herbert and Saper, 1990; Grigson et al., 1997a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999) and it has been shown that norepinephrine influences the release of CRF (Guillaume et al., 1987; Koob, 1999) and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (Szafarczyk et al., 1987). Taken together, NTS neurons may coordinate the autonomic regulation of the limbic and amygdalar brain regions via targeting CRF neurons in these regions.

We have also shown that some non-catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS bifurcate to the PGi and the CNA. These non-catecholaminergic neurons are located in the caudal NTS which corresponds to the distribution of some neuropeptides known to project to the PGi and the CNA. These include enkephalin, neurotensin and somatostatin (Riche et al., 1990; Zardetto-Smith and Gray, 1990). In addition, it is also likely that the catecholaminergic neurons that send collateralized projections to the PGi and the CNA may also contain some of these neuropeptides. Further studies would be useful to elucidate whether these collaterals contain neuropeptides or other co-transmitters.

In summary, the present results demonstrate that the catecholaminergic neurons originating from the NTS simultaneously relay information to the PGi and the CNA. This pathway may provide an anatomical substrate for the coordinated responses of the PGi and the CNA neurons to autonomic events.

Acknowledgments

Supported by DA 09082 and 15395 to E.V.B.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CNA

central nucleus of the amygdala

- CRF

corticotropin releasing factor

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PGi

nucleus paragigantocellularis

- PNMT

phenylethanolamine-N-methlytransferase

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- WGA-Au-HRP

wheat germ agglutinin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase coupled to gold

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aicher SA, et al. Monosynaptic projections from the nucleus tractus solitarii to C1 adrenergic neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: comparison with input from the caudal ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:62–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960909)373:1<62::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GV, Cechetto DF. Functional and anatomical organization of cardiovascular pressor and depressor sites in the lateral hypothalamic area: I. Descending projections. J Comp Neurol. 1992;315:313–332. doi: 10.1002/cne.903150307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler SM, et al. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the rat: sensory ganglia and nuclei of the solitary and spinal trigeminal tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:248–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller KM, et al. NTS catecholamine cell recruitment by hemorrhage and hypoxia. Neuroreport. 1999;10:3853–3856. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199912160-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RK, Sawchenko PE. Hemodynamic regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase messenger RNA in medullary catecholamine neurons: a c-fos-guided hybridization histochemical study. Neuroscience. 1995;66:377–390. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00600-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RK, Sawchenko PE. Organization and transmitter specificity of medullary neurons activated by sustained hypertension: implications for understanding baroreceptor reflex circuitry. J Neurosci. 1998;18:371–387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00371.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello J, et al. Central projections of baroreceptor afferent fibres in the rat. In: Robin I, Barraco A, editors. Nucleus of the solitary tract. CRC Press; London: 1994. pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EC, Williams CL. Adrenergic activation of the nucleus tractus solitarius potentiates amygdala norepinephrine release and enhances retention performance in emotionally arousing and spatial memory tasks, Behav. Brain Res. 2000;112:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA, et al. Role of ventrolateral medulla in vasomotor regulation: a correlative anatomical and physiological study. Brain Res. 1982;249:223–235. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA, Moon EA. Role of ventrolateral medulla in vasomotor response to cerebral ischemia, Am. J Physiol. 1980;239:H349–358. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.3.H349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeno TM, Brody MJ. Hemodynamic responses to amygdaloid stimulation in spontaneously hypertensive rats, Am. J Physiol. 1983;245:R281–286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.245.2.R281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeno TM, et al. Contribution of the amygdala to the development of spontaneous hypertension. Brain Res. 1982;246:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, et al. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: II. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract in Na+ appetite, conditioned taste aversion, and conditioned odor aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:169–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, et al. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: III. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the parabrachial nucleus in retention of a conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume V, et al. The corticotropin-releasing factor release in rat hypophysial portal blood is mediated by brain catecholamines. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;46:143–146. doi: 10.1159/000124811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RB, Norgren R. Central projections of gustatory nerves in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;222:560–577. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock MB. Evidence for direct projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract onto medullary adrenaline cells. J Comp Neurol. 1988;276:460–467. doi: 10.1002/cne.902760310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper RM, et al. State-dependent alteration of respiratory cycle timing by stimulation of the central nucleus of the amygdala. Brain Res. 1984;306:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert H, Saper CB. Cholecystokinin-, galanin-, and corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactive projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:581–598. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes SM, et al. Most neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarii do not send collateral projections to multiple autonomic targets in the rat brain, Exp. Neurol. 2006;198:539–551. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokfelt T, et al. Distribution maps of tyrosine-hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. In: Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, editors. Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy Classical transmitters in the CNS. Vol. 2. Elsevier Science Publishers; Amsterdam: 1984. pp. 277–379. Part I. [Google Scholar]

- Jia HG, et al. Evidence of gamma-aminobutyric acidergic control over the catecholaminergic projection from the medulla oblongata to the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1997;381:262–281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970512)381:3<262::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, et al. Rat medulla oblongata. II Dopaminergic, noradrenergic (A1 and A2) and adrenergic neurons, nerve fibers, and presumptive terminal processes. J Comp Neurol. 1985;233:308–332. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp BS, et al. Cardiovascular responses elicited by electrical stimulation of the amygdala central nucleus in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1982;234:251–262. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90866-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, et al. Fluorescent latex microspheres as a retrograde neuronal marker for in vivo and in vitro studies of visual cortex. Nature. 1984;310:498–500. doi: 10.1038/310498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Iarovici DM. Green fluorescent latex microspheres: a new retrograde tracer. Neuroscience. 1990;34:511–520. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress, Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick TA. Convergent afferent inputs to neurones in nucleus paragigantocellularis lateralis in the cat. Brain Res. 1988;456:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskati HAA, Zbroayma AW. Cardiovascular and motor components of the defense reaction elicited in rats by electrical and chemical stimulation in amygdala. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1989;28:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(89)90085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM. Location of neurones with cardiovascular and respiratory function, at the ventral surface of the cat's medulla. Neuroscience. 1986;18:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM, et al. Effects of kainic acid applied to the ventral surface of the medulla oblongata on vasomotor tone, the baroreceptor reflex and hypothalamic autonomic responses. Brain Res. 1982;238:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Williams CL. Enhancement of noradrenergic neurotransmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract modulates memory storage processes. Brain Res. 2003;987(2003):164–175q. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Williams CL. Peripheral arousal-related hormones modulate norepinephrine release in the hippocampus via influences on brainstem nuclei, Behav. Brain Res. 2004;153:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mtui EP, et al. Medullary visceral reflex circuits: local afferents to nucleus tractus solitarii synthesize catecholamines and project to thoracic spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1995;351:5–26. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AZ, et al. Directionally specific changes in arterial pressure induce differential patterns of fos expression in discrete areas of the rat brainstem: a double-labeling study for Fos and catecholamines. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:36–50. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R. Projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. Neuroscience. 1978;3:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Zaborszky L. Neuroanatomy of central cardiovascular control. Nucleus tractus solitarii: afferent and efferent neuronal connections in relation to the baroreceptor reflex arc. Prog Brain Res. 1977;47(1977):9–34. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; New York: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, et al. The limbic region. II. The amygdaloid complex. In: Bjorklund A, et al., editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Vol. 5. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1987. pp. 279–388. [Google Scholar]

- Punnen S, et al. Cardiovascular response to injections of enkephalin in the pressor area of the ventrolateral medulla. Neuropharmacology. 1984;23:939–946. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo JA, Koh ET. Anatomical evidence of direct projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the hypothalamus, amygdala, and other forebrain structures in the rat. Brain Res. 1978;153:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riche D, et al. Neuropeptides and catecholamines in efferent projections of the nuclei of the solitary tract in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:399–424. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roder S, Ciriello J. Innervation of the amygdaloid complex by catecholaminergic cell groups of the ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332:105–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, et al. Tonic vasomotor control by the rostral ventrolateral medulla: effect of electrical or chemical stimulation of the area containing C1 adrenaline neurons on arterial pressure, heart rate, and plasma catecholamines and vasopressin. J Neurosci. 1984;4:474–494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-02-00474.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, et al. Afferent projections to cardiovascular portions of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;223:402–408. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, et al. Projections from the nucleus tractus solitarii to the rostral ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 1985;242:511–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.902420405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, et al. Excitation by morphine and enkephalin of single neurons of nucleus reticularis paragigantocellularis in the rat: a probable mechanism of analgesic action of opioids. Brain Res. 1979;169:406–410. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessle BJ, Henry JL. Effects of enkephalin and 5-hydroxytryptamine on solitary tract neurones involved in respiration and respiratory reflexes. Brain Res. 1985;327:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura T, et al. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: I. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract during a brief intake test in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, et al. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafarczyk A, et al. Further evidence for a central stimulatory action of catecholamines on adrenocorticotropin release in the rat. Endocrinology. 1987;121:883–892. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-3-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, et al. Light and electron microscopic evidence for topographic and monosynaptic projections from neurons in the ventral medulla to noradrenergic dendrites in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1998;784:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, et al. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: substrate for the co-ordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrin. 1998;10:743–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, et al. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Anatomic basis for differential regulation of the rostrolateral peri-locus coeruleus region by limbic afferents. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pickel VM. Ultrastructure of serotonin-immunoreactive terminals in the core and shell of the rat nucleus accumbens: cellular substrates for interactions with catecholamine afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334:603–617. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, et al. Diverse afferents converge on the nucleus paragigantocellularis in the rat ventrolateral medulla: retrograde and anterograde tracing studies. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:561–584. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg DH, et al. Catecholamine content of individual brain regions of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SH-rats) Brain Res. 1976;112:429–434. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston M, et al. Fos expression by glutamatergic neurons of the solitary tract nucleus after phenylephrine-induced hypertension in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:525–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnen HJ, et al. Elevated adrenaline content in nuclei of the medulla oblongata and the hypothalamus during the development of spontaneous hypertension. Brain Res. 1978;157:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, et al. The effects of noradrenergic activation of the nucleus tractus solitarius on memory and in potentiating norepinephrine release in the amygdala, Behav. Neurosci. 2000;114:1131–1144. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardetto-Smith AM, Gray TS. Organization of peptidergic and catecholaminergic efferents from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the rat amygdala. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:875–887. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90183-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardetto-Smith AM, Gray TS. Catecholamine and NPY efferents from the ventrolateral medulla to the amygdala in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1995;38:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]