Abstract

Objective:

The authors sought to validate the ISGPF classification scheme in a large cohort of patients following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in a pancreaticobiliary surgical specialty unit.

Summary Background Data:

Definitions of postoperative pancreatic fistula vary widely, precluding accurate comparisons of surgical techniques and experiences. The ISGPF has proposed a classification scheme for pancreatic fistula based on clinical parameters; yet it has not been rigorously tested or validated.

Methods:

Between October 2001 and 2005, 176 consecutive patients underwent PD with a single drain placed. Pancreatic fistula was defined by ISGPF criteria. Cases were divided into four categories: no fistula; biochemical fistula without clinical sequelae (grade A), fistula requiring any therapeutic intervention (grade B), and fistula with severe clinical sequelae (grade C). Clinical and economic outcomes were analyzed across all grades.

Results:

More than two thirds of all patients had no evidence of fistula. Grade A fistulas occurred 15% of the time, grade B 12%, and grade C 3%. All measurable outcomes were equivalent between the no fistula and grade A classes. Conversely, costs, duration of stay, ICU duration, and disposition acuity progressively increased from grade A to C. Resource utilization similarly escalated by grade.

Conclusions:

Biochemical evidence of pancreatic fistula alone has no clinical consequence and does not result in increased resource utilization. Increasing fistula grades have negative clinical and economic impacts on patients and their healthcare resources. These findings validate the ISGPF classification scheme for pancreatic fistula.

Widely varying definitions of postoperative pancreatic fistula preclude accurate and objective comparisons of surgical techniques and clinical outcomes. The International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme, originally proposed to establish consensus, is validated herein according to numerous clinical and economic parameters.

Pancreatic fistula is widely regarded as the most ominous of complications following pancreatic resection. Its clinical impact and sequelae have been previously described and shown to contribute to the development of other morbid complications and high rates of mortality.1–4 Despite refinements in operative technique and advancements in postoperative management, fistulas still occur with a frequency of 5% to 30%.5–12 Efforts to mitigate this problem have included technical considerations (modification of the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis technique, reconstruction with pancreaticogastrostomy, and placement of pancreatic duct stents), perioperative infusion of somatostatin analogues, and use of adhesive sealants.9 However, the successes of these various techniques and pharmacologic adjuvants is frequently challenged, and dissension exists as to which methods are optimal for prevention and management of fistulas.

The debate is further compounded by numerous and widely varying definitions of pancreatic fistula. Data from a recent analysis of 4 widely accepted definitions of fistula reported in the gastrointestinal surgical literature demonstrates that fistula rate depends largely upon the definition used.13 The lack of a universal definition of pancreatic fistula, therefore, precludes objective comparisons of surgical experiences with this complication.

To address this problem and develop a consensus approach, an international consortium of 37 leading pancreatic surgeons from 15 countries, the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF), convened, reviewed the literature, and discussed their surgical experiences with fistulas.14 The result was a universal and applicable definition of pancreatic fistula and a grading system for fistula severity based on clinical impact on the patient.

Appraisal of this grading system has yet to be accomplished, and to date, the ISGPF clinical classification scheme has not been rigorously tested or validated. The aims of this study, therefore, are: 1) to analyze our experience with pancreatic fistula by applying the ISGPF classification scheme in a high-volume pancreatico-biliary surgical specialty unit; 2) to demonstrate its value in examining outcomes in a large cohort of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy; and 3) to validate its application, clinically and economically, as a suitable alternative to current biochemical definitions of fistula.

METHODS

Patients

Two surgeons performed 176 pancreaticoduodenectomies from October 2001 to January 2006, with either classic resection (n = 33) or pylorus-preserving modification (n = 143). All patients were taken to the operating room with intent for curative or palliative resection of suspected periampullary neoplasms, pancreatitis, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, or cystic neoplasms. Final pathology revealed that the majority of patients had ductal adenocarcinoma (n = 65). Other pathologies encountered included periampullary malignancies (n = 27), chronic pancreatitis (n = 28), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (n = 15), cystic neoplasms (n = 5), and other conditions (n = 36).

Surgical Technique

Following proximal resection of the pancreas, a pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis was constructed in a duct-to-mucosa, end-to-side fashion, with either a single- or two-layer interrupted anastomosis. A single layer was favored and was most commonly performed (n = 106). Ductal stents were seldom used (n = 21). No pancreaticogastrostomies were performed. Prophylactic octreotide was given subcutaneously (dose 150 μg every 8 hours) and continued postoperatively in 86 patients considered high risk for pancreatic fistula based on gland texture and duct size. A single drain was routinely placed anterior to the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis and exteriorized through the lateral abdominal wall. Multiple drains were placed in 5 patients, who were thought to be at high risk for either pancreatic or biliary fistula development.

Postoperative Management

All patients were treated by a standardized postoperative carepath for pancreatic resection used at our institution. Outputs from all operatively placed drains were recorded daily for at least 6 postoperative days. Amylase levels were obtained from drains on or after postoperative day 6, usually following tolerance of a soft solid diet. In those patients with more than one operatively placed drain, amylase levels were obtained from the drain known to be overlying the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis. All patients had drains removed at the operating surgeon's discretion. Drains were removed if amylase levels were below 3 times normal. They were maintained longer if patients had high amylase levels, generous fluid output, or sinister appearance to the effluent, defined in the original ISGPF scheme as “varying from a dark brown to greenish bilious fluid to milky water to clear spring water that looks like pancreatic juice.”14 Computed tomography was used to assess for fluid collections whenever indicated based on clinical suspicion (n = 34). Those requiring drainage underwent percutaneous computed tomography (CT)-guided drainage (n = 5, 3%). Additional management methods for suspected fistulas included administration of antibiotics, subcutaneous octreotide, and supplemental (ie, parenteral or enteral) nutritional support.

Data Collection

All aspects of care were directed by the operating surgeon. Data on preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care were prospectively collected and maintained on a secure database. Preoperative parameters include patient demographics (ie, age, gender, and medical history), presenting symptoms (ie, jaundice, weight loss, diarrhea, pain), laboratory tests, prior imaging studies, and preoperative therapies (ie, endoscopic ductal stenting or sphincterotomy). Intraoperative parameters include total blood loss, operative time, fluid resuscitation, blood transfusions, and gland characteristics, as well as the use of drains, stents, or somatostatin analogues. Postoperative events and clinical outcomes were recorded, and include therapeutic and diagnostic strategies, nutritional support, laboratory and imaging studies, recovery of gastrointestinal function, incidence and type of complications, intensive care unit (ICU) transfers and duration, initial hospital duration, discharge disposition, and any hospital readmissions, reoperations, or mortality (defined as death during the initial hospitalization or within 30 days of hospital discharge, or death due to any surgical complication at any point in time). All economic data were collected and analyzed using Casemix TSI.

Analysis and Classification of Pancreatic Fistula

A detailed analysis of the data and clinical course was performed for each of the 176 consecutive patients individually. Pancreatic fistula, according to ISGPF criteria, was defined as any measurable drainage from an operatively placed drain (or a subsequently placed percutaneous drain) on or after postoperative day 3, with an amylase content greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal serum amylase level (>300 IU/L). All patients below this threshold were considered to have no fistula.

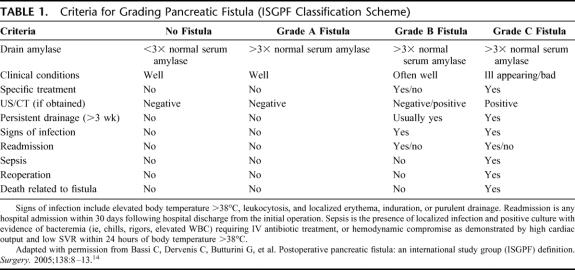

Three grades of fistula severity were classified according to ISGPF clinical criteria.14 ISGPF grades for each patient were determined only after complete postoperative follow-up was accomplished. Table 1 summarizes these grades of fistula based solely on 10 parameters. These criteria are intended to provide a summary of the main features of each fistula grade. A fistula is classified according to a particular grade if at least one criterion for that particular grade occurs.

TABLE 1. Criteria for Grading Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF Classification Scheme)

No Fistula Patients

The No Fistula group of patients lacks both elevated drain amylase levels and any clinical sequelae of fistula. Treatments specific for pancreatic fistula management (ie, somatostatin analogues, percutaneous drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections) are neither required nor instituted. Patients without pancreatic fistulas may suffer from other complications with varying (sometimes severe) clinical manifestations, but these are not attributed to pancreatic fistula.

Grade A Fistulas

Grade A fistulas are transient, asymptomatic fistulas, with only elevated drain amylase levels. The clinical sequelae of pancreatic fistula do not manifest in these fistulas. Consequently, treatments or deviations in clinical management are not required for this fistula grade. Drains are removed within 3 weeks, almost always within the first 7 days following the operation. Diagnostic imaging studies, if obtained at all, do not reveal worrisome or suspicious peripancreatic collections. Antibiotics, supplemental nutrition, somatostatin analogues, percutaneous drainage, reoperation, and readmission for fistula management are neither required nor employed for this group.

Grade B Fistulas

Grade B fistulas are symptomatic, clinically apparent fistulas that require diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic management. Patients may complain of abdominal pain, fever, nausea, intolerance to oral intake, or other bowel-related symptoms. Diagnostic imaging studies may show worrisome or suspicious peripancreatic fluid collections. Antibiotic therapy, supplemental nutrition, and/or percutaneous drainage are indicated to control and prevent exacerbation of grade B fistulas. Operatively placed drains may remain in situ at the time of discharge and are frequently required for management longer than 3 weeks.

Grade C Fistulas

Grade C fistulas are severe, clinically significant fistulas that require major deviations in clinical management. In addition to supplemental nutrition, intravenous antibiotics, and somatostatin analogues, aggressive therapeutic interventions are unquestionably warranted. Drainage from operatively placed drains persists for several weeks, while diagnostic imaging studies demonstrate worrisome peripancreatic fluid collections. Patients with these fistulas, in contrast to grade B fistulas, appear ill and unstable, present in critical condition, and are susceptible to sepsis, organ dysfunction, even death. Surgical reexploration may be indicated for one of 3 options: 1) attempt to repair the site of leakage with wide peripancreatic drainage, 2) conversion to alternative means of pancreatic-enteric anastomosis, and 3) total pancreatectomy.

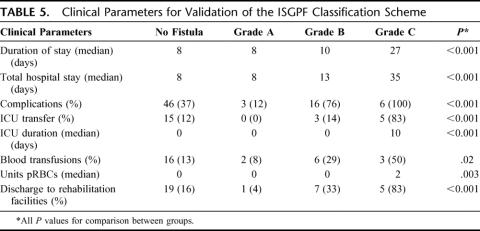

Clinical Validation of ISGPF Criteria

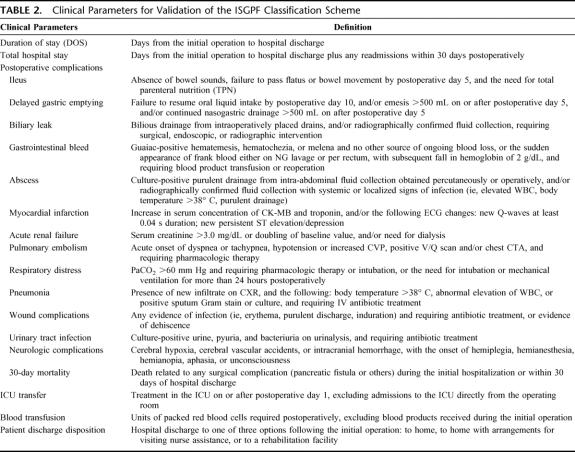

Validation of the ISGPF classification scheme is accomplished through the analysis and comparison of clinically relevant parameters not already included in the ISGPF scheme. The following are considered clinically relevant parameters: index duration of stay, total hospital stay, complications, ICU transfers and duration, blood transfusions, and discharge disposition. Table 2 defines these clinical parameters. Total hospital stay differs from duration of stay in that it includes any hospital readmissions within 30 days postoperatively. These hospital readmissions are considered to better represent the full impact of pancreatic fistula management.

TABLE 2. Clinical Parameters for Validation of the ISGPF Classification Scheme

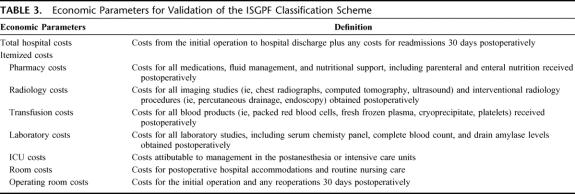

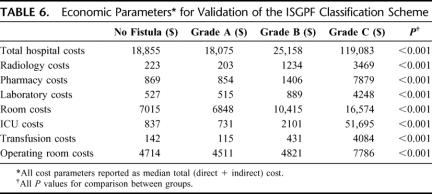

Economic Validation of ISGPF Criteria

Further validation of the ISGPF classification scheme is achieved by evaluating economic parameters across fistula grades. Again, this includes costs from all hospitalizations within 30 days of the index operation. Overall hospital and itemized costs were separately considered. Table 3 defines these economic parameters.

TABLE 3. Economic Parameters for Validation of the ISGPF Classification Scheme

Statistical Analysis

Fistula grades were compared using the χ2 statistic, Analysis of variance, and the Student t tests. Factors associated with fistula severity were calculated based on cross-tabulations using χ2 statistic and the Pearson correlation test. Statistical significance was accepted at a P value <0.05. All statistical computations were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 14.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Pancreatic Fistula

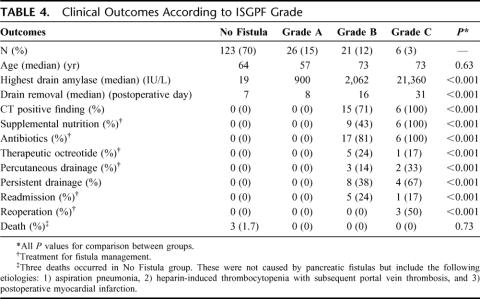

All patients met criteria for evaluation by the ISGPF classification scheme. Fifty-three patients had a fistula for an overall incidence of 30.1%. There were 26 grade A fistulas (14.8% overall), 21 grade B fistulas (11.9% overall), and 6 grade C fistulas (3.4% overall). Table 4 lists the clinical outcomes for each fistula grade. Overall, there were 6 readmissions (3.4%), 3 reoperations (1.7%), and no deaths attributable to pancreatic fistula. Antibiotics were administered for fistula management in 22 of 53 patients (41.5%), supplemental nutrition was initiated for 15 patients (28.3%), and percutaneous drainage was infrequently required (9.4%).

TABLE 4. Clinical Outcomes According to ISGPF Grade

Grade A Fistulas

Grade A fistulas comprised half (49%) of all fistula cases (26 of 53). The median maximal drain amylase level for this fistula grade was 900 IU/L. Although 38% of patients maintained a drain at hospital discharge, none had persistent drainage longer than 3 weeks, and all had drains removed within that timeframe (median, 8 days; range, 7–20 days). This variability in drain removal upon discharge reflects the surgeon's clinical judgment as customary drain removal was delayed in some cases based on extremely high amylase levels, higher than expected volume, or curious fluid characteristics at the time of discharge. Specific treatments for grade A fistulas were neither indicated nor administered. Only 2 patients with this fistula type required any diagnostic imaging, and in both patients, CT failed to show peripancreatic fluid collections. No patient had persistent drainage for more than 3 weeks. Readmissions or reoperations did not occur for this fistula grade.

Grade B Fistulas

Grade B fistulas occurred in 21 patients (40% of fistula cases). The median maximal drain amylase level was 2062 IU/L. Drains were removed on postoperative day 16 (median). All patients received at least one specific treatment of fistula management, most commonly antibiotics (81%), supplemental nutrition (43%), and octreotide therapy (24%). The majority of patients (71%) had CTs positive for suspicious fluid collections, with 20% of these cases (3 of 15) accessible to percutaneous drainage. The remainder was treated conservatively with observation and/or antibiotics. Compared with other fistula grades, grade B fistulas most frequently required drains be left in situ at hospital discharge (62%) and often necessitated hospital readmission (24%).

Grade C Fistulas

Grade C fistulas occurred in only 6 patients overall (11% of all fistula cases). While the initial median drain amylase level was only 27 IU/L, additional measurements in the postoperative period were significantly elevated (21,360 IU/L). Consequently, all patients required specific treatments. Drains were removed on postoperative day 31 (median). Sepsis occurred in 5 patients (83%). Supplemental nutrition (100%) and antibiotics (100%) were the most common treatment modalities, followed by minimally invasive drainage (33%) and therapeutic octreotide (17%). CTs were obtained for all 6 patients, and all demonstrated worrisome peripancreatic fluid collections. These fistulas were treated in the following fashion: 1) surgical exploration (n = 3), 2) percutaneous drainage (n = 2), and 3) antibiotics and observation (n = 1). Despite the severity of these fistulas, no fistula-related death occurred in any patient.

Clinical Validation

Clinical parameters, distinct from those employed in the ISGPF classification scheme, were considered for all patients. Table 5 lists these parameters and their outcomes for each fistula grade.

TABLE 5. Clinical Parameters for Validation of the ISGPF Classification Scheme

The duration of stay for grade A fistulas and all No Fistula patients was 8 days for each; yet, surprisingly this approached statistical significance (P = 0.06). This is explained by the inclusion of patients in the No Fistula group (37%), who suffered other complications exclusive of pancreatic fistula. These naturally resulted in a significantly longer duration of stay (10 days) when compared with grade A fistulas (P < 0.001). Conversely, the No Fistula patients, who had no postoperative complications (63%), were effectively discharged within 8 days. Therefore, this group was equivalent to the grade A fistulas, and statistical significance was not achieved (P = 0.80).

More importantly, duration of stay progressively increased as fistula severity escalated from A to C (grade A, 8 days; grade B, 10 days; grade C, 27 days). Analogously, total hospital stay was shortest for grade A fistulas and longest for grade C fistulas (grade A, 8 days; grade B, 13 days; grade C, 35 days).

The incidence of complications exclusive of pancreatic fistula was further compared across all fistula grades. Overall, 71 of 176 patients (40.3%) developed complications other than pancreatic fistula. Patients with grade A fistulas seldom (12%) developed complications. The incidence of complications, however, was significantly increased for patients with grade B and C fistulas (76% and 100%, respectively). Wound infections (29%), postoperative ileus (24%), and intra-abdominal abscess (19%) were commonly observed with grade B fistulas, while 50% of grade C patients developed intra-abdominal abscesses, gastrointestinal bleeding, wound infections, and respiratory failure. Delayed gastric emptying rarely occurred in association with pancreatic fistula (4%).

Approximately 13% of all patients required ICU management at any time postoperatively. No patient who developed a grade A fistula was transferred to the ICU, compared with 3 patients with grade B fistulas (14%). Grade C fistulas, on the other hand, frequently demanded aggressive ICU management (83%). Examination of the median ICU duration further supports these findings, as grade C patients remained in the ICU longest, for a median 10 days.

Blood transfusions were frequently required for patients who developed fistulas (Table 5). Overall, 11 of 53 patients with pancreatic fistula (21%) received blood products in the postoperative period, 9 of which had grade B or C fistulas. The number of units of packed red blood cells was greatest for patients with grade C fistulas (median 2 units).

Patient discharge disposition was also compared across all fistula grades (Table 5). Patients who developed grade A or B fistulas were often discharged to home (96% and 67%, respectively), while patients with grade C fistulas were more regularly discharged to rehabilitation facilities (83%).

Economic Validation

To further validate the ISGPF classification scheme, fiscal parameters for each fistula grade were analyzed and compared (Table 6). A detailed analysis of these fistula grades demonstrates the mild severity of grade A fistulas, and the costly effects of grade B and C fistulas. Economically, grade A patients are no different from patients who lack complications, pancreatic fistula or otherwise ($18,075 vs. $18,209, P = 0.68). However, patients in the No Fistula cohort, who suffered other complications, had significantly greater hospital costs than patients with grade A fistulas ($23,885 vs. $18,075, P = 0.005).

TABLE 6. Economic Parameters for Validation of the ISGPF Classification Scheme

Furthermore, as fistula severity increased from grade A to C, all cost metrics correspondingly escalated. Costs for resource utilization, including radiology, pharmacy, laboratory, and transfusion costs, were lowest for grade A fistulas (P < 0.001).

Itemized costs for grade B fistulas, across all parameters, were significantly greater than those for grade A fistulas (P < 0.01), yet significantly lower than those for grade C fistulas (P < 0.01). Frequent diagnostic evaluations and therapeutic management for this fistula grade were reflected in increased radiology, pharmacy, and laboratory costs (P < 0.01). ICU costs, though increased, did not exceed room costs, and illustrate the limited ICU requirements for patients with this fistula grade.

For patients with grade C fistulas, ICU costs exceeded room costs, and comprised 43% of overall hospital costs for this fistula grade. These high ICU costs indicate that grade C fistulas frequently require management in the ICU, as demonstrated by a median ICU duration approximately one third that of the total duration of stay (10 days vs. 27 days, respectively). Resource utilization was subsequently greatest for patients who developed grade C fistulas. Combined radiology, pharmacy, laboratory, and transfusion costs alone ($19,680) rival overall hospital costs for grade A ($18,075) and grade B fistulas ($25,158).

Examination of operating room (OR) costs further reveals differences between the fistula grades. Costs of the original operation for these grade C fistulas ($4885) were equivalent to those for No Fistula ($4714), grade A ($4511), and grade B ($4821) classes (P = 0.63), indicating no predisposing factor from the index operation toward development of a severe clinical fistula. However, significantly increased overall median OR costs were observed for grade C fistulas ($7786), demonstrating the number of patients with this fistula grade who required surgical reexploration for management of pancreatic fistula. This reoperative endeavor equated to roughly $3000 of extra cost per patient in this group.

Grade B Versus Grade C

According to the ISGPF classification scheme, only 3 objective criteria differentiate a grade C fistula from a grade B classification: the onset of sepsis, the need for surgical reexploration, and/or death attributable to pancreatic fistula. However, we questioned whether these parameters could adequately demarcate these 2 grades. We therefore independently compared these 3 specific parameters, as well as other clinical and economic outcomes, between these 2 categories of fistula.

Five patients (83%) with grade C fistulas met criteria for the development of sepsis, and 3 (50%) underwent surgical reexploration. These rates were statistically significant (P < 0.001) when compared with patients with grade B fistulas, who by definition, neither developed sepsis nor required surgical intervention. Although previous studies consistently demonstrate a strong correlation between pancreatic fistula and mortality, this event did not occur in our series. Indeed, only 3 deaths (1.7%) occurred overall and were attributed to 1) aspiration pneumonia, 2) heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with subsequent portal vein thrombosis, and 3) postoperative myocardial infarction. Conversely, no patients who suffered a pancreatic fistula in this series expired during the initial hospitalization or at any point in time following hospital discharge.

While the overall incidence of complications was higher among grade C fistulas (100% vs. 76%), these rates were statistically equivalent (P = 0.20). Nevertheless, significant differences in duration of stay, total hospital stay, and rates of ICU transfers were observed between the 2 groups. When compared with grade B fistulas, the duration of stay for grade C fistulas was nearly 3 times as long (10 vs. 27 days, P < 0.001); similarly, the total hospital stay was significantly increased (13 vs. 35 days, P < 0.001). Furthermore, patients with severe grade C fistulas more often required management in intensive care settings (14% vs. 83%, P < 0.001) and discharge to rehabilitation facilities (33% vs. 83%, P = 0.03). Finally, total hospital costs, as well as most itemized costs, ie, radiology, pharmacy, laboratory, ICU, transfusion, operating room, were significantly higher (P < 0.02) among patients with grade C fistulas. These findings demonstrate that the ISGPF classification scheme appropriately distinguishes between pancreatic fistulae of moderate and severe severity.

DISCUSSION

After pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreatic fistula contributes to increased rates of postoperative complications, longer hospital stays, as well as considerable physical and emotional morbidity for patients. In the past decade, there has been debate as to what defines a pancreatic fistula, and it appears the incidence is contingent on what definition is used. This weakens ongoing analysis of the problem and potentially weakens objective comparisons across clinical trials, and among the literature in general.

Bassi et al,13 in retrospective fashion, examined 26 definitions of pancreatic fistula in the previous 10 years. Among those definitions, 4 were deemed suitable and were then applied to a group of 242 patients who underwent pancreatic resection with pancreatico-jejunal anastomotic reconstruction. The authors determined the incidence of pancreatic fistula ranged between 9.9% and 28.5%, depending on the defining criteria. This variance obviously precludes accurate comparisons of techniques and outcomes.

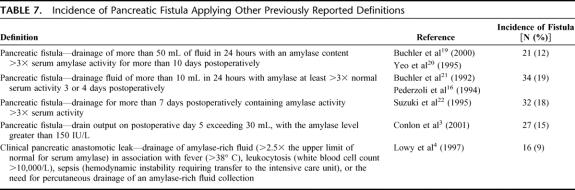

Our experience mirrors theirs. Five generally acceptable definitions of pancreatic fistula were applied to the same cohort of 176 patients at our institution. Table 7 lists these definitions.3,4,16,19–22 Pancreatic fistula, applying these definitions, ranged between 9.1% and 19.3%.

TABLE 7. Incidence of Pancreatic Fistula Applying Other Previously Reported Definitions

In addition to the widely varying incidence of pancreatic fistula, biochemical definitions assume all pancreatic fistulas are the same and that they do not present with varying degrees of clinical severity. However, not all fistulas are significant, and in fact, some may be clinically silent. Biochemical definitions of fistula alone do not consider the true clinical impact on a patient.

In July 2005, the ISGPF developed and published a universal definition and classification scheme for pancreatic fistula, based on the clinical impact of pancreatic fistulas.14 A broad definition of fistula was favored to include all peripancreatic fluid collections, abscesses, leaks, and fistulas thought to manifest from poor anastomotic healing. Validation and acceptance of this novel definition and grading system will require several appraisals in other specialty surgical units, and to date, this is the first. The current study critically and objectively examines the ISGPF classification scheme and its relevance in a high volume pancreatico-biliary surgical specialty setting. Clinical and economic parameters, distinct from the defining ISGPF criteria, were judged for comparison and evaluation, and correspondingly worsen as fistula severity increases. Grade A fistulas present with an elevated drain amylase only and lack any clinical consequences. Duration of stay, rates of complications, ICU transfers, and blood transfusion are not significantly increased, and hospital costs are equivalent to those patients without pancreatic fistula. Grade B fistulas require therapeutic interventions and behave in an intermediate fashion. Duration of stay, rates of complications, and ICU transfers are marginally increased, and radiology, pharmacy, and laboratory costs are all higher than costs for grade A fistulas. Grade C fistulas are the most severe fistulas, with dramatic impacts on patients. Hospital stays are substantially longer, and patients frequently require ICU transfers for sepsis management. Aggressive interventions are indicated and often include surgical exploration. These 3 fistula grades, as described by the ISGPF classification scheme, are distinct and validated based on varying clinical and economic outcomes for each. However, strong conclusions regarding grade C fistulas must be tempered by their infrequent occurrence.

Our experience with the ISGPF classification scheme has enabled further evaluation of outcomes within our clinical management protocol for pancreatic resection. Pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign and malignant disease occurs in 30% of patients. However, half of all fistulas are clinically silent. These fistulas, defined as grade A fistulas, presented with biochemical evidence of fistula (ie, elevated drain amylase) but lacked any clinical sequelae. If not included, our clinically significant postoperative pancreatic fistula rate becomes 15%. Furthermore, all clinical and economic outcomes for patients with this fistula grade were equivalent to those for patients who did not develop pancreatic fistula. Our findings are consistent with previously reported studies that examined whether elevated drain fluid amylase adequately reflects fistula severity.

Shyr et al15 described 37 patients who underwent either classic pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticojejunostomy or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. Daily drain fluid amylase was observed for each patient, and 57% had an elevated drain amylase on postoperative day 1. On postoperative day 7, however, only 30% had a drain amylase at least 3 times greater than the upper limit of normal serum amylase, yet none developed clinical manifestations of pancreatic fistula. Only 1 patient, with a drain amylase level of 74 IU/L and a drainage amount of 10 mL, developed a clinical pancreatic fistula. The authors concluded that biochemical fistulas, defined by amylase-rich drainage fluid, have no clinical significance and do not always result in clinical sequelae. Our current study supports these findings and indicates biochemical evidence of fistula alone has neither clinical consequence nor economic impact.

Clinically significant fistulas, on the other hand, negatively impact patients and demand aggressive healthcare resource utilization. Our application of the ISGPF classification scheme in a specialized pancreaticobiliary surgical specialty unit has demonstrated that morbidity rates, duration of stay, ICU transfer rates, and hospital costs dramatically increase for patients with clinically significant fistulas, and that these patients often require outpatient healthcare resources and rehabilitative services. These results are consistent with earlier studies on clinically relevant pancreatic fistulas. Lowy et al4 described similar findings from a prospective, randomized clinical trial involving 110 patients randomized to receive either octreotide or no further treatment after pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignant disease at a single institution. All 17 patients who were classified as having a biochemical pancreatic fistula recovered uneventfully and had no clinical consequences, while 10 patients who developed clinical manifestations of pancreatic fistulas experienced higher rates of complications and increased hospital stays. These findings, along with results from the current study, suggest that only clinical pancreatic fistulas impact patient outcomes and that biochemical pancreatic fistulas remain clinically and economically insignificant. These findings further emphasize that a clinical definition for pancreatic fistula may in fact be more useful than a biochemical definition. The new ISGPF classification scheme offers a simple clinical definition of pancreatic fistula and is valuable in categorizing and delineating the impact of increasing fistula severity.

A second problem with using biochemical definitions is the inability to determine fistula development or quantify fistula severity in patients who lack an operatively placed drain from which amylase levels are obtained. Many surgeons criticize the value of intraperitoneal drains after hepatobiliary and pancreatic resections, and have adopted management techniques without intraoperative drain placement.3,23 In such cases, pancreatic fistula, according to biochemical criteria, can be defined only after percutaneous drainage or reoperation ensue. Biochemical definitions are not useful in assessing fistula development, and consequently, the reported incidence of fistula is likely an underapproximation of the actual incidence. The ISGPF classification scheme offers a solution to this problem, by providing other objective criteria that define fistula development in situations where an amylase level cannot be assessed, or otherwise is not obtained.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that the ISGPF classification scheme can be useful in assessing contemporary outcomes in a specialized pancreaticobiliary surgical unit. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that it is a suitable and preferred alternative to biochemical definitions of fistula, in that it accurately delineates and evaluates the impact of increasing fistula severity. Finally, we have validated the ISGPF classification scheme, both clinically and economically, by examining several clinical and economic parameters distinct from ISGPF criteria. However, rigorous appraisal at other institutions is necessary to further justify its use and to enable accurate comparisons of surgical techniques and management experiences with this difficult and costly complication.

Footnotes

Supported by the Clinical Research Fellowship Program at Harvard Medical School offered by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Harvard PASTEUR Program and Office of Enrichment Programs (to W.B.P.).

Reprints will not be available. Correspondence: Charles M. Vollmer, Jr, MD, Department of Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Avenue, ST 9, Boston, MA 02215. E-mail: cvollmer@bidmc.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Wit LT, Van Gulik TM, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conlon KC, Labow D, Leung D, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 2001;234:487–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowy AM, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of octreotide to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignant disease. Ann Surg. 1997;226:632–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, et al. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB. 2005;7:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartoli FG, Arnone GB, Ravera G, et al. Pancreatic fistula and relative mortality in malignant disease after pancreaticoduodenectomy: review and statistical meta-analysis regarding 15 years of literature. Anticancer Res. 1991;11:1831–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsiotos GG, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Are the results of pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer improving? World J Surg. 1999;23:913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon RT, Lo SH, Fong D, et al. Prevention of pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassi C, Falconi M, Salvia R, et al. Management of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high volume centre: results on 150 consecutive patients. Dig Surg. 2001;18:453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balcolm JH, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, et al. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassi C, Butturini G, Molinari E, et al. Pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatic resection: the importance of definitions. Dig Surg. 2004;21:54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shyr YM, Su CH, Wu CW, et al. Does drainage fluid amylase reflect pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy? World J Surg. 2003;27:606–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Falconi M, et al. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of complications of elective pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deleted in proof.

- 18.Deleted in proof.

- 19.Buchler MW, Friess H, Wagner M, et al. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg. 2000;87:883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM, et al. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 222:580–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchler M, Friess H, Klempa I, et al. Role of octreotide in the prevention of postoperative complications following pancreatic resection. Am J Surg. 1992;163:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y, Morita A, et al. Fibrin glue sealing for the prevention of pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1995;130:952–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heslin MJ, Harrison LE, Brooks AD, et al. Is intra-abdominal drainage necessary after pancreaticoduodenectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]