Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of an aggressive strategy in patients presenting peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) from colorectal cancer with or without liver metastases (LMs) treated with cytoreductive surgery (CS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

Patients and Methods:

The population included 43 patients who had 54 CS+HIPEC for colorectal PC from 1996 to 2006. Sixteen patients (37%) presented LMs. Eleven patients (25%) presented occlusion at the time of PC diagnosis. Ascites was present in 12 patients (28%). Seventy-seven percent of the patients were Gilly 3 (diffuse nodules, 5–20 mm) and Gilly 4 (diffuse nodules>20 mm). The main endpoints were morbidity, mortality, completeness of cancer resection (CCR), and actuarial survival rates.

Results:

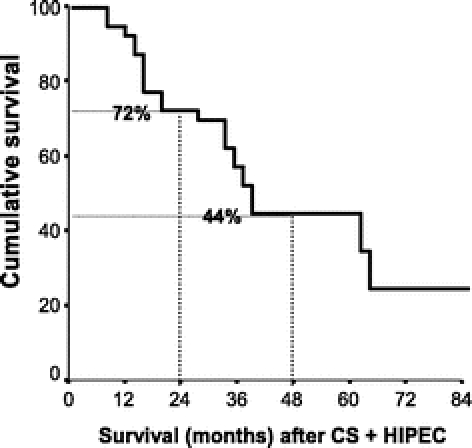

The CS was considered as CCR-0 (no residual nodules) or CCR-1 (residual nodules <5 mm) in 30 patients (70%). Iterative procedures were performed in 26% of patients. Three patients had prior to CS + HIPEC, 10 had concomitant minor liver resection, and 3 had differed liver resections (2 right hepatectomies) 2 months after CS + HIPEC. The mortality rate was 2.3% (1 patient). Seventeen patients (39%) presented one or multiple complications (per procedure morbidity = 31%). Complications included deep abscess (n = 6), wound infection (n = 5), pleural effusion (n = 5), digestive fistula (n = 4), delayed gastric emptying syndrome (n = 4), and renal failure (n = 3). Two patients (3.6%) were reoperated. The median survival was 38.4 months (CI, 32.8–43.9). Actuarial 2- and 4-year survival rates were 72% and 44%, respectively. The survival rates were not significantly different between patients who had CS + HIPEC for PC alone (including the primary resection) versus those who had associated LMs resection (median survival, 35.3 versus 36.0 months, P = 0.73).

Conclusion:

Iterative CS + HIPEC is an effective treatment in PC from colorectal cancer. The presence of resectable LMs associated with PC does not contraindicate the prospect of an oncologic treatment in these patients.

A median survival rate of 34 months is reported after cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for advanced stage peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer with or without liver metastases.

The prognosis of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) from colorectal cancer is poor.1 It represents one of the most common causes of death in patients with digestive malignancies with an overall median survival of 6 months.2–6 Therefore, these patients are considered as being in the terminal phase of their disease, and receive palliative and/or symptomatic treatments.7

In the past 10 years, a growing number of publications have shown that multimodal treatment of patients with PC, including extensive cytoreductive surgery (CS) followed by hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), could significantly improve the survival of patients with colorectal PC.1,7,8 However, the appropriate selection of candidates who can potentially benefit from this costly procedure still remains difficult.1,8–11 Regarding this point, patients with visible macroscopic disease on CT scan and/or concomitant liver metastases (LMs), ascites, or occlusive syndrome, are for some centers a contraindication for CS + HIPEC.9,11

As a tertiary university-hospital center, we have focused our efforts in the last 15 years on multimodal treatment of patients with PC according to the Sugarbaker et al recommendations.12,13 As a general policy, and especially from 1996, we decided to apply an aggressive strategy aimed at reducing the peritoneal nodules in patients with colorectal PC even in those who had resectable LMs and/or ascites and/or occlusive syndrome. The aim of this study is to report the long-term results of our aggressive multimodal strategy in patients with PC from colorectal origin with or without LMs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

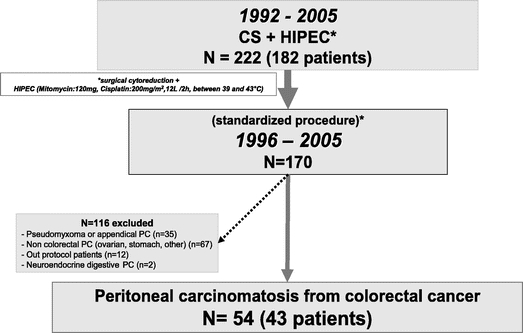

From September 1992 to September 2005, 222 CS + HIPEC were performed in 182 patients. From October 1996, 170 CS + HIPEC were standardized as follows: 1) all patients had extensive CS aiming to minimize the residual peritoneal disease to a completeness of cancer resection (CCR-0): no macroscopic residual cancer or CCR-1: no residual nodule greater than 5 mm in diameter14; 2) 2 synergic drugs: mitomycin-C and cisplatin were used for HIPEC; 116 CS + HIPEC were excluded for analysis because PC was not from colorectal origin (n = 104) or protocol violation (n = 12) (Fig. 1). Fifty-four CS + HIPEC for PC of colorectal origin performed in 43 patients without extra-abdominal disease were included in the study. Patients with (preoperative or intraoperative) ascites, presenting an occlusive syndrome and/or resectable LM, were included if creatinine clearance was superior to 50 mL/min. PC was considered as synchronous to the primary tumor if it was diagnosed less than 3 months after the colorectal tumor.

FIGURE 1. Study design. CS, cytoreductive surgery; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Demographic data (sex, age), previous treatments including systemic chemotherapy, surgical procedures and intraoperative data (presence of an occlusive state, number of digestive anastomoses, simultaneous resection of primary tumor or LMs, presence or absence of lymph node metastases), and finally the completeness of CS were noted.

Surgical Technique and HIPEC Procedure

Surgery was performed through a large midline incision. All adhesions were liberated, especially in the pelvis. The first part of the procedure was to record the extent of PC by the Gilly et al classification3: malignant nodules less than 5 mm in diameter localized in one part of the abdomen (Gilly I), diffuse malignant nodules less than 5 mm nodules in diameter (Gilly II), localized or diffuses malignant nodules from 5 mm to 2 cm in diameter (Gilly III), and localized or diffuse malignant nodules greater that 2 cm in diameter (Gilly 4). The small intestine and the posterior face of the stomach and both right and left subdiaphragmatic regions, as well as the great omentum (up to spleen hilum), and the inferior part of the lesser gastric ligament were routinely resected. If present, the primary tumor was resected. In patients with occlusion, the first objective of the CS was to remove the malignant tumors greater than 0.5 cm in diameter that might cause occlusive syndrome. If the parietal and/or the diaphragmatic peritoneum were involved by diffuse malignant nodules, a subtotal peritonectomy was performed as recommended by Carmignani and Sugarbaker.13,15 At the end of the procedure, patients were classified upon CCR classification.14

Depending on the surgeon choice, anastomoses were performed either before or after HIPEC. However, since 1996, anastomoses were preferentially performed after HIPEC, because of possible, although not proved, adverse effect of hyperthermia on sutured zones. At the end of cytoreduction, if present, small residual mesenteric nodules were fulgurated with argon beam. After CS, the abdomen was washed with a warmed saline solution (2–5 L at 37°C), then one inflow catheters with 2 thermal catheters were placed in the right and/or left superior abdominal quadrants controlling the inflow and interior abdominal temperatures. Two suction drains were placed in the lower part of right and left abdominal quadrants. Over the last 5 years, HIPEC were performed by an open technique (coliseum).

HIPEC was performed as follows: 12 L of perfusion solution (6 L of mitomycin-C, 120 mg and 6 L of cisplatin, 200 mg/m2 of body surface) were prepared in a neuter solution. All the liquids were warmed at a temperature of 47°C to 50°C for intraperitoneal perfusion. The intraperitoneal perfusion was delivered for 90 to 120 minutes with an inflow temperature of 45°C and to obtain a deep abdominal temperature of 41°C to 43°C. Thirty minutes before intraperitoneal perfusion of cisplatin, 16 gr/m2 of sodium thiosulfate was given iv for over 6 hours. After the procedure, 3 suction drains were placed for 5 days in the abdomen (two under diaphragm and one in the pelvis). All the patients were placed in the ICU for at least 7 days. All the patients were evaluated clinically and morphologically every 3 to 6 months.

In patients with resectable LMs, if LMs required minor liver resections, tumorectomies or segmentectomies were performed at the same operative time after CS and before HIPEC. If LMs required major and/or complex hepatectomy, liver resection (such as right hepatectomy) was delayed to 2 months after CS + HIPEC usually through an elective incision (bi-subcostal or J shaped incision).

Statistical Analysis

Standard parametric and nonparametric tests were used as appropriate. Means were expressed with their corresponding standard deviation. The main endpoint was survival measured as time from initial procedure with combined CS + HIPEC to death or point date. Other judgment criteria were the number of patients with one or more postoperative complications, type of complications, mortality, morbidity rates, and hospital stay. The survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and comparison of curves was made using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using SPSS software (11.5 version). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Endpoints

Major endpoints were short- and long-term survivals as well as hospital stay, morbidity (according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria), mortality (including death during the 30 postoperative days).

RESULTS

Patient Population

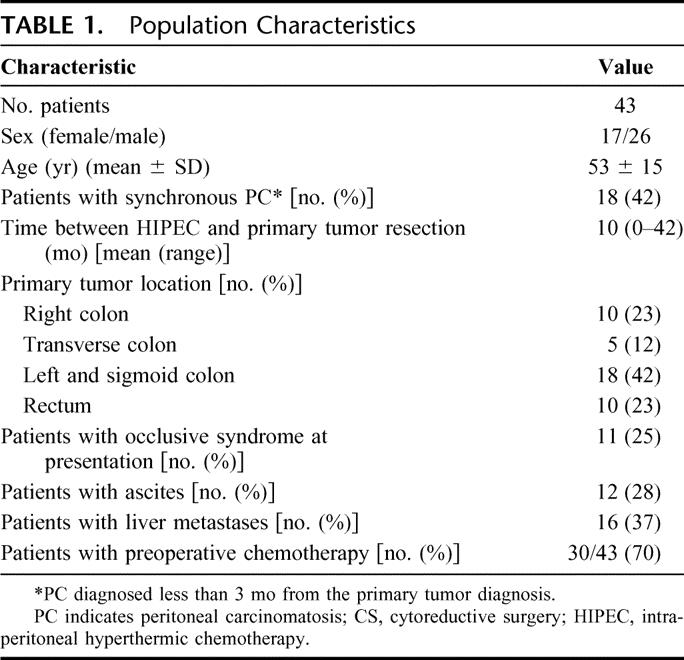

The population characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sixteen patients had hepatic metastasis (37%). Ascites was present in 12 (28%) patients. An occlusive syndrome was present in 11 (25%) patients. Seventy percent of patients received prior systemic chemotherapy.

TABLE 1. Population Characteristics

Treatment

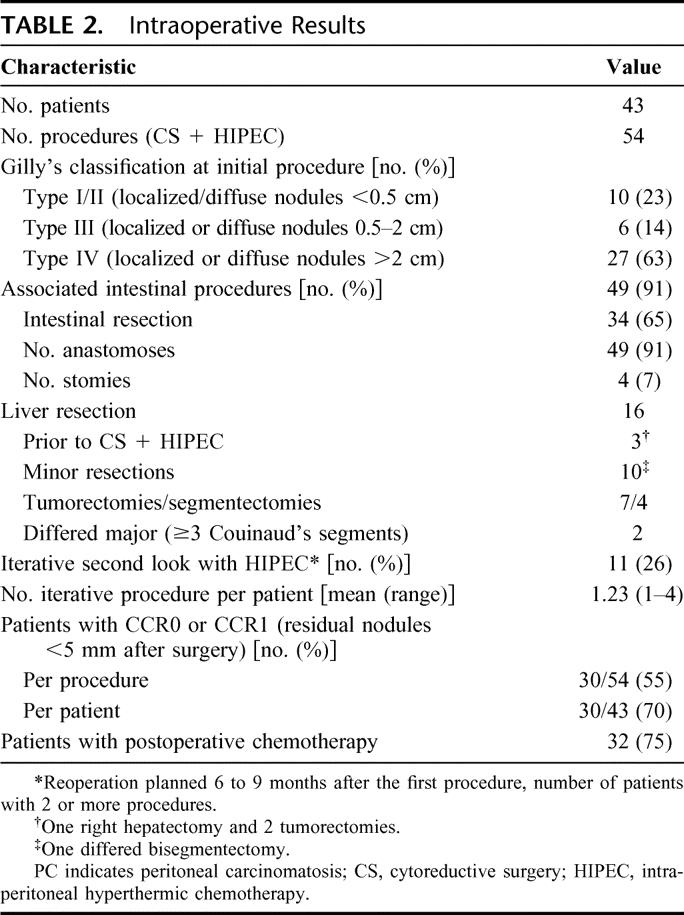

Perioperative results are shown in the Tables 2 and 3. Seventy-seven percent of patients had macroscopic diffuse peritoneal disease: Gilly III (14%) and Gilly IV (63%). Among 16 patients with LMs, 3 had prior liver resections (1 right hepatectomy and 2 metastasectomies), 10 had simultaneous minor liver resections during CS + HIPEC (7 tumorectomies or 3 segmentectomies), and 3 had differed major liver resections including 2 right hepatectomies 2 months after CS + HIPEC.

TABLE 2. Intraoperative Results

TABLE 3. Postoperative Results

Thirty four patients (65%) had concomitant digestive resections followed by 49 anastomoses and 4 stomies. An iterative procedure was performed in 11 patients (26%). The mean number of iterative procedures (second-look) per patient was 1.23. Among patients with iterative procedures, the median number of CS + HIPEC was 2 (highest number of second-looks, 4). By performing iterative CS + HIPEC, the percentage of patients with CCR-0 or CCR-1 resection increased from 50% after one procedure to 75% (Table 2). Thirty-two patients (75%) had postoperative systemic chemotherapy after resection of the primary and 82% after CS + HIPEC (89% of them received 5-fluorouracil [5-FU] + oxaliplatin and/or 5-FU + irinotecan).

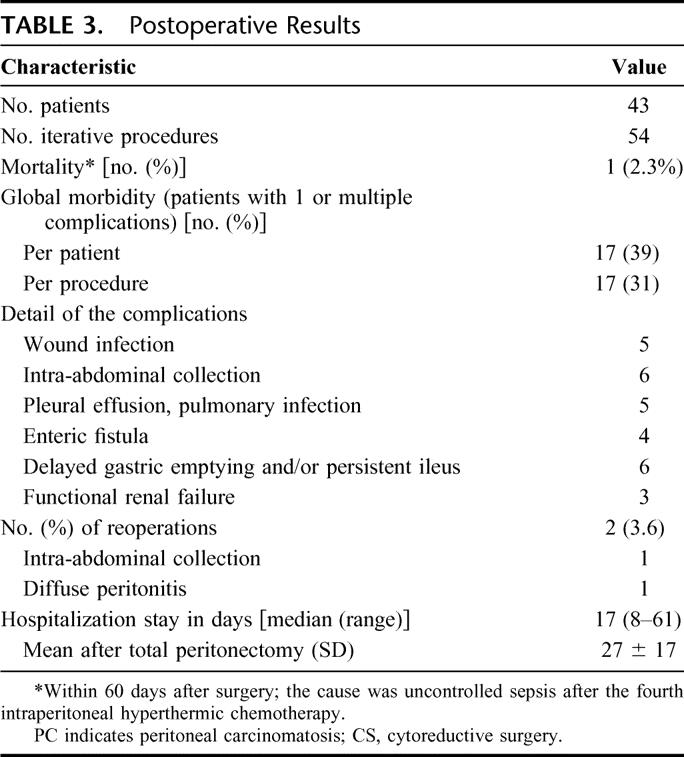

Postoperative data including morbid-mortality rates are presented in Table 3. One patient (2.3%) died of uncontrollable septic shock. The overall morbidity rate was 39% per patient and 31% per procedure. The main complications were deep abdominal abscess and fistula, pulmonary complications, and renal failure (Table 3). Reoperation was required in 2 patients: one for peritonitis and one for deep collection. Fifteen patients (14%) presented a persistent ileus (>10 days). A prolonged (2 weeks) postoperative fever (37.8C–38.4°C) without demonstrable cause was present in 65% of patients. The median postoperative in-hospital stay was 17 days (range, 8–61 days). The mean hospital stay between patients who underwent extensive surgery including subtotal peritonectomy extended to the diaphragm was statistically longer than those without subtotal peritonectomy: 27 ± 17 days versus 18 ± 10 days, respectively (P < 0.01).

Survival

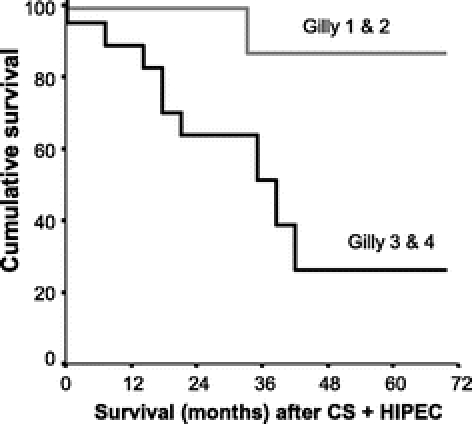

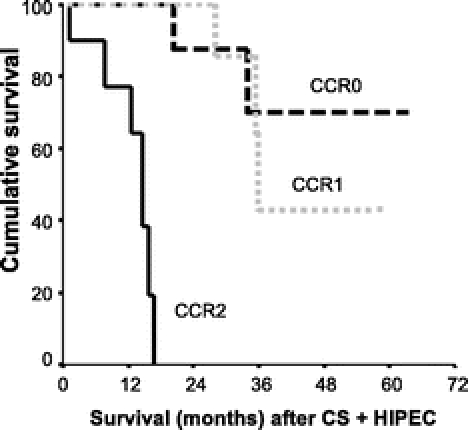

The overall median survival was 38.4 months (confidence interval, 32.8–43.9). The 2- and 4-year survival rates were 72% and 44%, respectively (Fig. 2). Two significant prognostic factors were found after univariate analysis: the initial extent of CP according to Gilly’s classifications (P = 0.014; Fig. 3) and the completeness of CS (CCR-0, CCR-1, and CCR-2) (P < 0.0001 = 0.37; Fig. 4). Other factors, such as age, sex, primary resection, occlusion, ascites, and simultaneous LM and PC resection, were not significant prognostic factors (P = not significant). The multivariate analysis on previous assumed prognostic factors showed that the status of CCR was the only significant prognostic factor (CCR-0/CCR-1 vs. CCR-2) (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 2. Overall actuarial survival (Kaplan–Meier). Median survival: 38.4 months (CI, 32.8–43.9 months). Two-year survival: 72%, 4-year survival: 44%. CS, cytoreductive surgery; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

FIGURE 3. Survival according to the extent of the initial disease (P = 0.009). Malignant nodules less than 5 mm in diameter localized in one part of the abdomen (Gilly 1), and diffuse nodules in the whole abdomen (Gilly 2) (gray line, median survival not reached). Localized or diffuse malignant nodules between 5 and 20 mm in diameter (Gilly 3) and large malignant nodules more than 20 mm in diameter (Gilly 4) (plain line, median survival: 33.8 months). CS, cytoreductive surgery; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

FIGURE 4. Survival according to the completeness of cancer resection (P < 0.0001). CCR-0, no macroscopic disease (black interrupted line; median survival not reached); CCR-1, residual disease less than 5 mm in diameter (gray interrupted line, median survival: 63 months). CCR-2: residual disease more than 5 mm in diameter (solid line; median survival: 14.6 months). CS, cytoreductive surgery; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

The presence of major associated procedures including primary, pelvectomy, and/or liver resections did not influence the long-term survival (P = 0.37). Patients with CS + HIPEC and liver resection had similar overall survival rates as compared with those who had CS + HIPEC alone, including the primary resection (median survival 36.0 vs. 35.3 months, P = 0.73). There was no statistical difference between patients who had preoperative or intraoperative ascites and/or those who presented an occlusive syndrome.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that in patients with advanced stage colorectal PC, iterative CS + HIPEC allowed achievement of appreciable long-term survival and acceptable morbidity-mortality rates. Moreover, similar long-term survival observed in patient who had LMs resection versus those without LM suggests CS + HIPEC in selected patients when both PC and LMs appear to be resectable.

Peritoneal cavity represents the unique site of metastatic disease in 25% of patients with recurrent colorectal cancer, even after a detailed diagnostic workup of the liver and lungs.6,16,17 Thus, PC is considered in some patients as the first step of dissemination and not as a generalized or an end-stage disease. This change of interpretation is fairly similar to that adopted over recent years toward patients presenting with multiple LMs.13,18,19 In the past 10 years, similar to the treatment of LM, a new rationale based on 2 complementary approaches emerged for a possible “cure” in patients with PC: 1) to perform a macroscopic complete CS, and 2) to treat the residual microscopic disease by local delivery of active drugs.10

Over the past 10 years, 20 papers have been published on the toxicity, complications, and survival results of trials investigating the morbidity, mortality, and therapeutic efficacy of CS followed by intraperitoneal chemotherapy either with or without hyperthermia in patients with PC of colorectal origin.1,10 Among them, 3 studies were comparative trials, 2 of which were randomized and only in 9 trials were patients with exclusive PC of colorectal origin included. The clinical outcomes with respect to long-term survival varied considerably. Median survival varied from 12 to 32 months. One-year, 2-year, 3-year and, when reported, 5-year survival rates varied from 65% to 90%, 25% to 60%, 18% to 47%, and 17% to 30%, respectively.1 The results of our series are encouraging in terms of survival and in accordance with reported series. In our series, two thirds of patients were Gilly III and IV stage, CS + HIPEC permitted to achieve a median survival of 38.4 months (confidence interval, 32.8–43.9) with 2-year and 4-year survival rates of 72% and 44%, respectively.1,10

Despite optimistic survival rates, appropriate patient selection remains difficult.1,10,11 Most of the authors admit that the benefit of HIPEC depends mainly on the capacity of the surgery to be complete (CCR-0 or CCR-1).1,10,11 However, no consensus is reported on the precise indications, intraoperative drug(s), different type of intraperitoneal drug delivery (close, open, with or without HIPEC machines); also, the extent of the peritoneal resection is not always easy to define.1,10,11 In addition, the real impact of iterative procedures on long-term survival has not been clearly reported.1 Some authors suggest avoiding operation in patients with occlusive syndrome and/or ascites or LMs.9–11 In our series, the most important factor regarding long-term survival was not the absence of occlusive syndrome, ascites, or LM but, as in most of the reported studies, the completeness of CS.2,10,13,14 Particularly, iterative surgery (second-look) was proposed in 26% of patients in this series. The routine second-look in our strategy allowed in 25% of the patient achievement of CCR-1/CCR-0 resection, especially in Gilly III/IV stage patients in whom the initial procedure was not complete (CCR-2). This policy was similar to the second-look strategy widely practiced in patients with ovarian20,21 and appendiceal PC.7,12,13,22,23 The rate of iterative procedures in our series is similar to the reported 30% of routine second-look for PC by Esquivel and Sugarbaker.23 Indeed, performing iterative procedures led us to obtain 70% CCR-1/CCR-0 of the population after second-look while only 50% of the population was considered as having complete resection after the first procedure. Between the 2 procedures, we actively tried to reinforce the nutrition status of the patient while these patients received active systemic chemotherapy. We think that patients with PC who could benefit from iterative procedures are those who did not develop extrahepatic/extra-abdominal and therefore might have less progressive PC disease.24,25

Mitomycin-C is the most frequently intraperitoneal cytostatic agent used alone or in combination with 5-FU or cisplatin.1,10 Since 1996, we used both mitomycin-C and cisplatin. Our results are similar to those reported by Elias et al26 (74% survival at 2 years) after the use of intraperitoneal oxaliplatin with iv 5-FU. Concerning, intraperitoneal drug delivery, substantial progress has been made notably by using HIPEC machines that increase the homogeneity of drugs delivery with stable temperature.4,8,27 Shen et al11 reported their results of HIPEC using mitomycin-C alone in 77 patients with colorectal PC. The overall 5-year survival rate was 17%, but only 34% of the patients had complete resection of macroscopic disease. As reported in the literature and in our series, we think that, independently to the nature of drugs, the completeness of cytoreductive surgery (CCR-0/CCR-1) remains the main prognostic factor influencing long-term survival.1,5,8,10,11,13,23,28,29 In this regard, we think that the management of LMs should be part of a multimodal multidisciplinary approach.18,25,30,31 The Amsterdam group demonstrated the superiority of CS + HIPEC over classic systemic chemotherapy in 104 randomized patients32; most of the patients with PC receive preoperative and postoperative systemic chemotherapy.13,18,31,33 In patients with demonstrable LMs, the performance of neoadjuvant chemotherapy helps to test the chemosensitivity of the LMs.18,31,33 In our opinion, patients with progressive disease especially under systemic chemotherapy are not good candidates for both LMs and PC resection.

Going farther, Carmignani and Sugarbaker13 clearly demonstrated that patients with synchronous intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal dissemination of mucinous adenocarcinoma, a good long-term survival rate, can be achieved by performing aggressive CS and HIPEC. In our series, the long-term survival did not differ between patients with or without LMs. Notably, the most important part of this strategy was the timing. This mainly depended on the number and location of LMs. To simplify, if LMs required minor and not complex resection(s), liver resection and HIPEC were performed at the same operative time. If LMs required complex or major liver resection(s), especially on an injured parenchyma (postchemotherapy liver), major liver resection was delayed from CS + HIPEC. This two-step surgery was already used in complex abdominal and liver surgeries mainly to reduce morbid-mortality of associating 2 major abdominal procedures.19,33 We think that, when both LM and PC are resectable, aggressive surgery can represent a chance for selected patients. Our findings are in accordance with those recently reported by the Institut Gustave Roussy group, which reported incidental PC discovered during abdominal exploration in 24 patients initially planned for hepatectomy for colorectal LM.30 In their series, the morbidity rate was 58%, and 3-year overall survival rate close to 42%. We think that, despite the small number of included patients in our series, selected patients could be good candidates for both the resection of the PC and LMs.

In our series, the rate of global morbidity per procedure was 31%, principally caused by intra-abdominal collections, enteric and anastomotic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, pleuropulmonary complications, and renal failure. One patient died (2.3%) after uncontrolled severe septic shock 2 months after the fourth iterative procedure. No significant hematologic toxicity was observed, although 3 patients represented a transient decrease in their platelet and white blood cells 2 to 3 weeks after HIPEC. None of them required platelet transfusion or GM-CSF therapy. Four patients presented immediate postoperative renal failure requiring treated by extensive filling, but none required hemodialysis. Among notable morbidities after HIPEC, we observed postoperative delayed gastric and intestinal emptying disorders requiring transient prokinetic drugs and parenteral nutrition, especially in patients who underwent an extensive adhesion lyses with subtotal peritoneum resection. Reported series showed that CS + HIPEC carry a high morbidity rate of between 14% and 55% and a mortality rate between 0% and 19%.1,10,32,34–37 These morbidity-mortality rates are mainly, but not exclusively, due to surgical complications: anastomotic leakage or bowel perforations36, toxicity.4,32,37 Three percent to 5% of patients died of treatment-related causes,4,36 comparable to our 2.3% of mortality. Notably, when a subtotal peritonectomy extending to both sides of the diaphragm was performed, a significant longer hospital stay was observed (21 days vs. 17 days, P < 0.05). This was mainly related to the presence of more intra-abdominal and pulmonary complications in patients who had extensive surgery, although the presence or absence of associated procedures such as simultaneous hepatectomy did not increase postoperative complications significantly.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study showed that CS, which treats macroscopic disease, combined with HIPEC, which treats the residual microscopic disease, is associated with appreciable long-term survival and acceptable morbidity-mortality rates even after iterative procedures. In addition, selected patients with resectable LM and PC could benefit from resection of both PC and LMs.

Footnotes

Reprints: Simon Msika, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Louis-Mourier University Hospital, 178 Rue des Renouillers, 92701 Colombes, Cedex, France. E-mail: simon.msika@lmr.aphp.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koppe MJ, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: incidence and current treatment strategies. Ann Surg. 2006;243:212–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elias D, Blot F, El Otmany A, et al. Curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from colorectal cancer by complete resection and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilly FN, Beaujard A, Glehen O, et al. Peritonectomy combined with intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia in abdominal cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis: phase I-II study. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:2317–2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glehen O, Mithieux F, Osinsky D, et al. Surgery combined with peritonectomy procedures and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia in abdominal cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugarbaker PH. Strategies for the prevention and treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:155–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal surface oncology: review of a personal experience with colorectal and appendiceal malignancy. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elias D, Delperro JR, Sideris L, et al. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: impact of complete cytoreductive surgery and difficulties in conducting randomized trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias D, Benizri E, Vernerey D, et al. Preoperative criteria of incomplete resectability of peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-appendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:1010–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3284–3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen P, Hawksworth J, Lovato J, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C for peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonappendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugarbaker PH, Jablonski KA. Prognostic features of 51 colorectal and 130 appendiceal cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1995;221:124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmignani CP, Sugarbaker PH. Synchronous extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal dissemination of appendix cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:864–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glehen O, Cotte E, Schreiber V, et al. Intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia and attempted cytoreductive surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Br J Surg. 2004;91:747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elias D, Pocard M. Treatment and prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin Noryh Am. 2003;12:543–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glehen O, Gilly FN, Sugarbaker PH. New perspectives in the management of colorectal cancer: what about peritoneal carcinomatosis? Scand J Surg. 2003;92:178–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayag-Beaujard AC, Francois Y, Glehen O, et al. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with digestive cancers with combination of intraperitoneal hyperthermia and mitomycin C. Bull Cancer. 2004;91:E113–E132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vauthey JN, Zorzi D, Pawlik TM. Making unresectable hepatic colorectal metastases resectable: does it work? Semin Oncol. 2005;32(suppl):118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawlik TM, Abdalla EK, Ellis LM, et al. Debunking dogma: surgery for four or more colorectal liver metastases is justified. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tournigand C. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: who and when? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugarbaker PH. Patient selection and treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal and appendiceal cancer. World J Surg. 1995;19:235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esquivel J, Sugarbaker PH. Second-look surgery in patients with peritoneal dissemination from appendiceal malignancy: analysis of prognostic factors in 98 patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gertsch P. A historical perspective on colorectal liver metastases and peritoneal carcinomatosis: similar results, different treatments. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 2003;12:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elias D, Pocard M, Sideris L, et al. Preliminary results of intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin in peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Br J Surg. 2004;91:455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elias D, El Otmany A, Bonnay M, et al. Human pharmacokinetic study of heated intraperitoneal oxaliplatin in increasingly hypotonic solutions after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncology. 2002;63:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugarbaker PH. Colorectal carcinomatosis: a new oncologic frontier. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glehen O, Mohamed F, Sugarbaker PH. Incomplete cytoreduction in 174 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from appendiceal malignancy. Ann Surg. 2004;240:278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elias D, Benizri E, Pocard M, et al. Treatment of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis and liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curley SA, Izzo F, Abdalla E, et al. Surgical treatment of colorectal cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737–3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kianmanesh R, Farges O, Abdalla EK, et al. Right portal vein ligation: a new planned two-step all-surgical approach for complete resection of primary gastrointestinal tumors with multiple bilateral liver metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, Witkamp A, et al. Long-term survival of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esquivel J, Vidal-Jove J, Steves MA, et al. Morbidity and mortality of cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Surgery. 1993;113:631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacquet P, Stephens AD, Averbach AM, et al. Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 60 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated by cytoreductive surgery and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer. 1996;77:2622–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens AD, Alderman R, Chang D, et al. Morbidity and mortality analysis of 200 treatments with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy using the coliseum technique. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]