Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether dedicated research time during surgical residency leads to funding following postgraduate training.

Summary Background Data:

Unlike other medical specialties, a significant number of general surgery residents spend 1 to 3 years in dedicated laboratory research during their training. The impact this has on obtaining peer reviewed research funding after residency is unknown.

Methods:

Survey of all graduates of an academic general surgery resident program from 1990 to 2005 (n = 105).

Results:

Seventy-five (71%) of survey recipients responded, of which 66 performed protected research during residency. Fifty-one currently perform research (mean effort, 26%; range, 2%–75%). Twenty-three respondents who performed research during residency (35%) subsequently received independent faculty funding. Thirteen respondents (20%) obtained NIH grants following residency training. The number of papers authored during resident research was associated with obtaining subsequent faculty grant support (9.3 vs. 5.2, P = 0.02). Faculty funding was associated with obtaining independent research support during residency (42% vs. 17%, P = 0.04). NIH-funded respondents spent more combined years in research before and during residency (3.7 vs. 2.8, P = 0.02). Academic surgeons rated research fellowships more relevant to their current job than private practitioners (4.3 vs. 3.4 by Likert scale, P < 0.05). Both groups considered research a worthwhile use of their time during residency (4.5 vs. 4.1, P = not significant).

Conclusions:

A large number of surgical trainees who perform a research fellowship in the middle of residency subsequently become funded investigators in this single-center survey. The likelihood of obtaining funding after residency is related to productivity and obtaining grant support during residency as well as cumulative years of research prior to obtaining a faculty position.

This study examines the impact of spending 1 to 3 years of laboratory research during surgical residency on subsequent faculty funding, by surveying graduates of a residency program from 1990 to 2005. Thirty-five percent obtained independent funding, and 20% received NIH funding. Productivity and funding during residency and total years of research training predicted faculty funding.

Of the 23 nonpreliminary specialties that participate in the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), general surgery is the only specialty where a sizable proportion of physicians extend their training by performing a 1- to 3-year postdoctoral research fellowship in the middle of their residency. This practice extends a 5-year postgraduate training program to 6 to 8 years at considerable financial and personal cost to both the trainee and the supporting department of surgery.

Surgeons have traditionally considered research to be an important part of residency training and faculty practice,1,2 although the exact number of surgery residents who perform a postdoctoral research fellowship in the middle of residency training is unknown. A 1994 survey of 189 residents who attended a course on surgical research demonstrated that half planned to enter the laboratory for 1 year and half planned for a 2- to 3-year research experience.3 According to the NRMP, there were 1051 nonpreliminary general surgical residency spots available in 2005, a number that has changed less than 5% over the last 6 years.4 Based upon this and the 1994 survey, we infer that at least 20% of all surgery residents have historically entered the laboratory each year. A more recent survey of all 20 general surgical residency programs in New England revealed that 48% of respondents participated in 1 to 3 years of dedicated research time in the middle of residency.5 Given the concentration of research-oriented programs in New England, this figure likely represents the upper limit estimation of the percentage of surgical residents across the country pursuing research time during residency.

Despite the large number of surgeons performing postdoctoral research fellowship during residency, surgeons are less likely to be funded and less likely to participate in peer review than other physician-scientists.6,7 How performing a postdoctoral research fellowship in the middle of surgical residency specifically translates into research success following graduate medical education is not well known, although a number of studies have partially addressed this question. First, 72% of members of 3 major academic surgical societies (Association of Academic Surgeons, Society of University Surgeons, and American Surgical Association) surveyed performed research during their training.8 Next, residents who ask to perform research time during residency have been demonstrated to be more likely to hold an academic position following residency.9,10 Finally, a study of pediatric surgeons found that publishing as a resident correlated with continued publications as an attending physician, although simply spending dedicated research time did not correlate with continued academic publication.11 However, despite the large numbers of surgeons in the laboratory at any given time, leaders in the field have recently concluded that: “although young surgeons in training and young surgical faculty present their research findings (often excellent work and important findings) at national meetings on a regular basis, no one knows how many residents work in research programs, who they are, where they are, or what they are doing. No one knows how many established surgeons are engaged in research today, who they are, where they are, or what they are doing.”6

The concept of extending residency by adding a dedicated research experience above and beyond the 5 clinical years necessary to become board eligible represents a unique paradigm in American medicine. However, it comes with obvious economic costs to the funding agencies that support this research and to the surgical trainees who add 1 to 3 years to their training with uncertain benefits. To determine how performing a postdoctoral research fellowship correlates to research following residency training, we surveyed all graduates of our academic general surgical residency program from 1990 to 2005 about research in their residency and postresidency careers.

METHODS

Participants

All graduates of the general surgery residency program at Washington University School of Medicine from 1990 to 2005 received the survey. Each was trained at Barnes-Jewish Hospital (formerly Barnes Hospital), a 1344-bed tertiary care, urban teaching hospital. The Department of Surgery was led by 2 chairmen throughout the course of the study and has an academic focus, demonstrated by its rank of second in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding to faculty members in 2004.12 A list of yearly graduates is kept by administrative records within the Department of Surgery. Each graduate was e-mailed a copy of the survey electronically in October 2005. Based upon the e-mail and mailing address of each graduate, it was determined in advance whether the surgeon was in an academic position or a private practice job. This pre hoc determination was performed to determine whether the respondents accurately reflected all survey recipients or whether academic surgeons would be more likely to respond based upon the nature of the survey. The study was approved by the human studies committee at Washington University School of Medicine, and informed consent was waived.

Survey

The survey asked 17 fact-based questions and 5 opinion questions. The fact-based questions were divided into research experience prior to residency (1 question), research experience, demographics, productivity, and funding applied for and received during surgical residency (8 questions) and in the first position following residency and current job (13 questions combined). The opinion questions queried residents about the utility of their dedicated research time to their residency experience and their current positions using a Likert scale. They also asked about the perceived utility of performing research for future surgical trainees.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed with the statistical software program Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Comparisons of 2 groups was done using unpaired t tests while comparison of 3 groups was done using ANOVA followed by the Tukey post-test. Contingency tables were compared using χ2 analysis. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

A total of 75 of 105 general surgical graduates (71%) completed the survey. Mean graduation year for respondents was 1997.9 compared with 1997.6 for all graduates (P = not significant). Twenty-seven percent of survey respondents are currently in private practice, while 33% of all survey recipients are currently in private practice (P = not significant).

Forty-five respondents (60%) had less than 1 year of research prior to starting residency, including 28 (37%) who had never performed research. Of the respondents with significant prior exposure, 16 (21%) had performed research for 1 year and 12 (16%) had performed research for greater than 2 years. Eight of this latter group (11%) obtained a PhD prior to beginning surgical training.

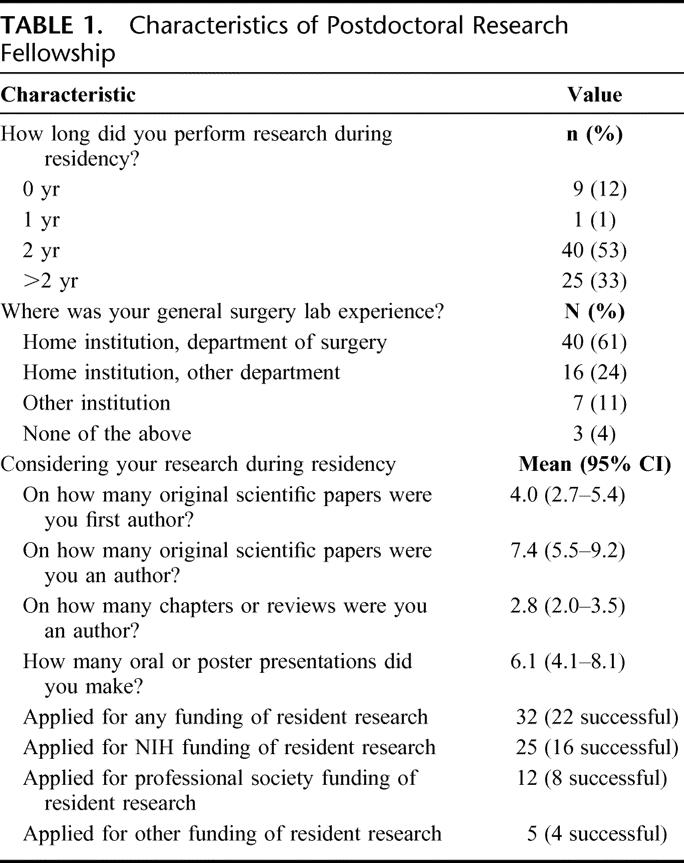

Postdoctoral Research Experience

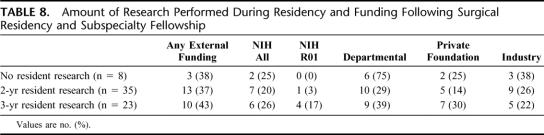

Sixty-five respondents (87%) completed 2 or more years of research during residency (Table 1). Of the remaining 10 respondents, 9 did not perform a postdoctoral research fellowship during residency training. Six of these people had previously obtained MD/PhD degrees, although 2 trainees with PhDs opted to spend an additional 2 years of dedicated laboratory time during their residencies.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Of the 65 respondents who spent 2 or more years performing research, 58 (89%) were in a basic science laboratory while 7 (11%) performed clinical research. Research was performed at multiple institutions in multiple academic departments, but greater than 60% of postdoctoral fellowships were in the Department of Surgery at the parent institution of the residency training program.

Trainees published an average of 7.4 peer-reviewed manuscripts during their postdoctoral fellowship, of which they were first author on 4.0 of them. In addition, respondents averaged 2.8 chapters or review articles and 6.1 oral or poster presentations at national meetings.

Half of respondents applied for independent peer-reviewed funding during their postdoctoral fellowships. Twenty-two of these grant applications (69%) were funded, meaning that 34% of surgical trainees applied for and received external grant support during their residencies. The majority of these were through the NIH.

Research Following Graduation From Surgical Training

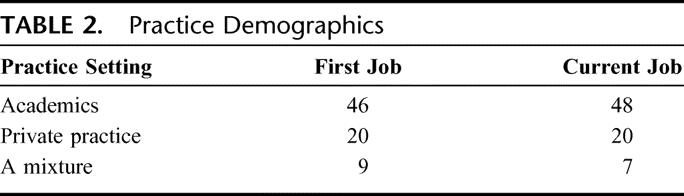

The majority of graduates from this academic training program took academic or mixed academic/private practice jobs after residency (Table 2). A similar percentage of respondents are currently in academic or mixed academic/private practice jobs. Of these, 11 individuals changed their practice setting, with 4 moving from private practice to an academic position and 3 moving from a faculty appointment to private practice. Two surgeons who initially had a mixed practice moved into academics while 1 moved into private practice. Whether a surgical trainee eventually took an academic, private practice or mixed job could not be predicted based upon length of research prior to residency or during residency, application for peer review funding during residency, or papers published during resident research. No association was found between respondents’ year of graduation with any variable measured, and the percentage of graduates pursuing academic careers remained stable for the past 15 years (data not shown).

TABLE 2. Practice Demographics

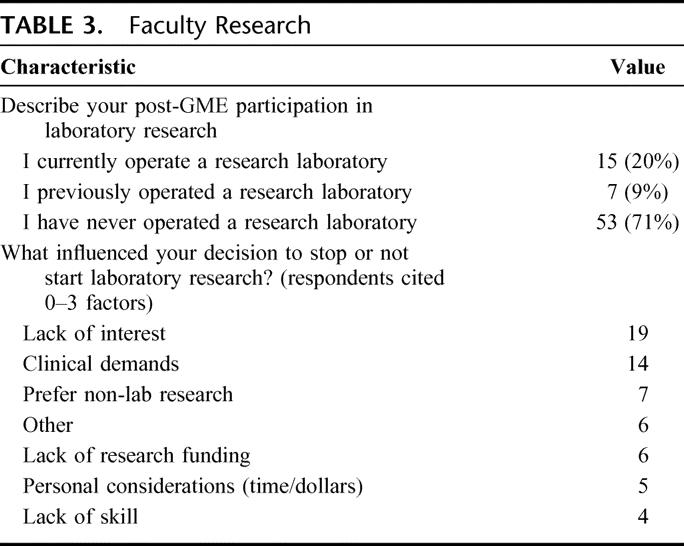

Fifty-five surgeons performed research at some point following residency. Of these, 51 surgeons currently perform research, while 4 do not. These numbers are identical for first job after residency (51 performed research, 24 did not), although 4 surgeons who initially performed research no longer do so and an equal number started performing research after their first job. Of those who are actively engaged in research activities, the average percent effort currently devoted to research is 26% (compared with 30% in first job following residency). The active percent effort ranges from 2% to 75%. Twenty-two respondents ran a research laboratory at some point following residency training (Table 3). Although most of respondents spent 2 to 3 years doing basic science research during residency, 33 surgeons (60% of those who performed research) exclusively did clinical research while on faculty. The most common reasons cited for not running a laboratory were lack of interest and clinical demands.

TABLE 3. Faculty Research

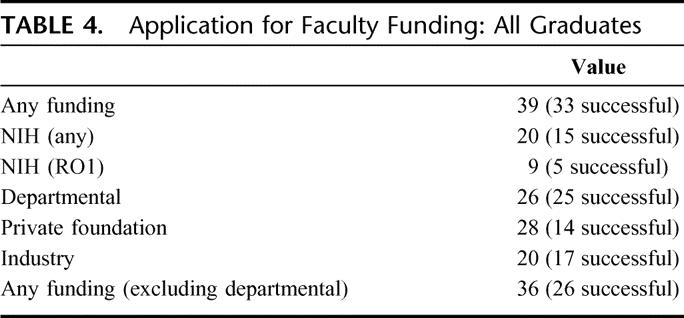

Thirty-nine of 55 respondents who performed research as a faculty member (regardless of whether they did research during residency) applied for research funding, with 33 successfully receiving funding (Table 4). Twenty respondents (27% of all respondents, 36% of respondents in academic or mixed jobs) applied for NIH grants and 15 received funding. Nine surgeons applied for R01 funding, and 5 were successful. Of note, 8 of 9 RO1 applicants had previously received NIH funding. The most common entity from which grant support was applied from was private foundations, with 28 of 39 grant applicants applying for funding through this mechanism. The majority of surgeons who applied for funding applied for more than one type of grant, and 21 of 33 grant recipients had more than one type of funding source. Excluding departmental funding (which was successful 96% of the time), 17 of 33 grant recipients had more than one funding source.

TABLE 4. Application for Faculty Funding: All Graduates

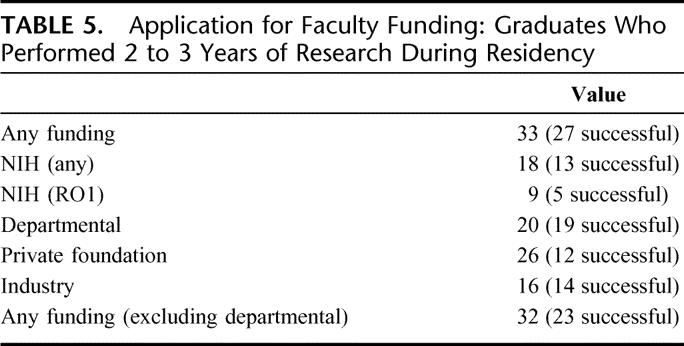

Of the surgeons (both academics and private practitioners) who performed research during surgical residency, 27 of 33 applicants received funding after residency (Table 5). Eighteen respondents applied for NIH grants and 13 received funding, for a success rate of 72%. All graduates who applied for or received an R01 spent 2 to 3 years in the laboratory during surgical residency. Eighteen of the grant recipients had more than 1 funding source.

TABLE 5. Application for Faculty Funding: Graduates Who Performed 2 to 3 Years of Research During Residency

Predictors of Funding Success Following Residency Training

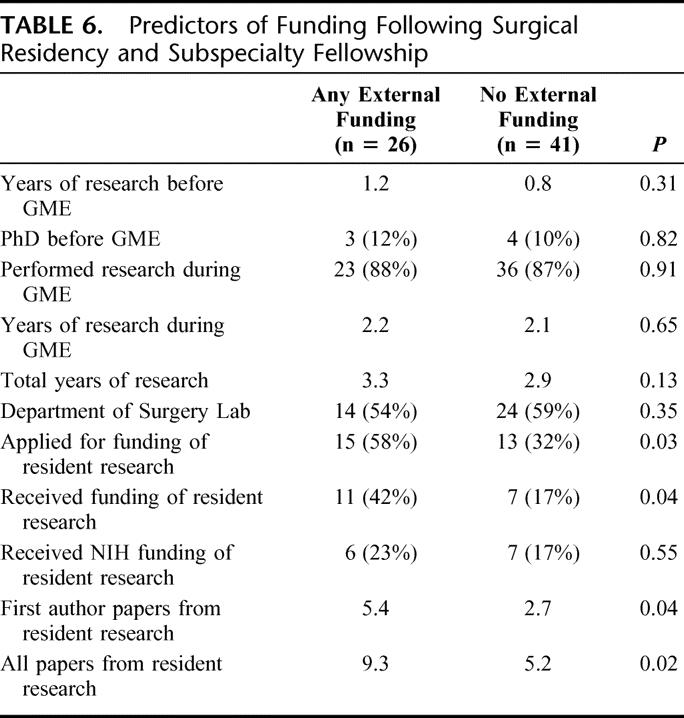

Comparing surgeons who received external funding of any type following surgical training to those who did not receive external funding, there was a significant association with both application and receipt of funding for research during surgical training (58% vs. 32% and 42% vs. 17%, respectively, P < 0.05, Table 6). Receipt of external funding following surgical training was also associated with both the total number of papers (9.3 vs. 5.2) and first author papers (5.4 vs. 2.7) during postdoctoral fellowship in surgical training (P < 0.05). Of note, this analysis includes 67 graduates of the program who are independent practitioners (regardless of whether they are in academics or private practice) but excludes 8 graduates who are currently in postresidency subspecialty fellowship programs since surgeons do not typically receive independent funding during subspecialty graduate medical education.

TABLE 6. Predictors of Funding Following Surgical Residency and Subspecialty Fellowship

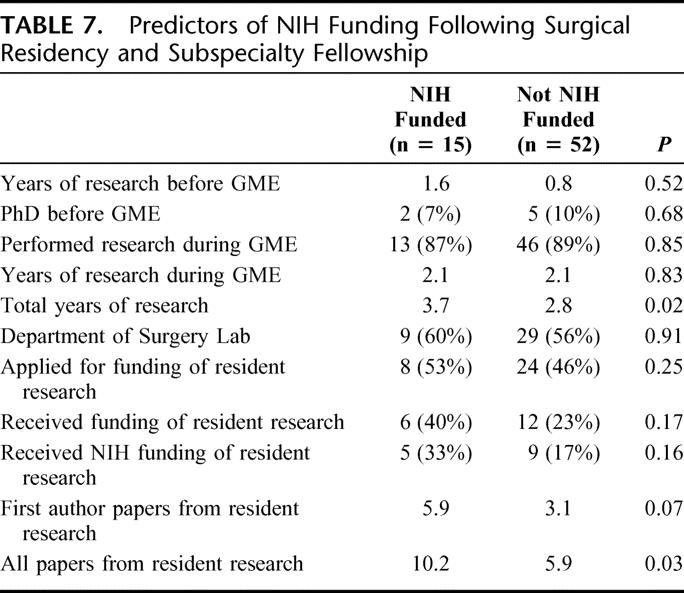

Comparing candidates who received NIH funding following surgical training with those who did not receive NIH funding (Table 7), the only predictive factors were total length of research before residency and during residency combined (3.7 vs. 2.8 years, P < 0.05) and papers published during residency (10.2 vs. 5.9, P < 0.05).

TABLE 7. Predictors of NIH Funding Following Surgical Residency and Subspecialty Fellowship

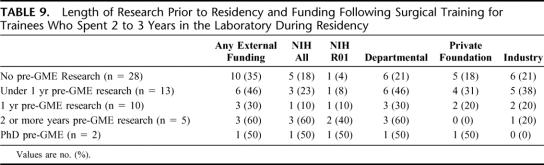

Length of time performing research during residency was not correlated to eventual funding (Table 8, P = not significant). Length of time performing research before residency was also not correlated to eventual funding with trainees who spent 2 to 3 years doing a postdoctoral fellowship during residency (Table 9, P = not significant).

TABLE 8. Amount of Research Performed During Residency and Funding Following Surgical Residency and Subspecialty Fellowship

TABLE 9. Length of Research Prior to Residency and Funding Following Surgical Training for Trainees Who Spent 2 to 3 Years in the Laboratory During Residency

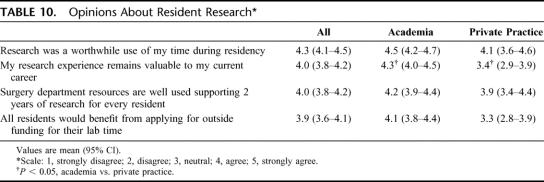

Surgeons’ Views Regarding the Utility of Postdoctoral Fellowship

Respondents were asked to evaluate several statements about research on a Likert scale (Table 10). Respondents felt that research training was a worthwhile use of their time during their residency, regardless of whether they are currently in academics or private practice. In contrast, surgeons in academics felt their postdoctoral fellowship was significantly more useful to their current career than private practitioners do. The survey also asked how many years a resident with undifferentiated career interests should spend in the laboratory, and the mean response was 1.7 years (95% confidence interval, 1.4–2.0).

TABLE 10. Opinions About Resident Research

DISCUSSION

There has been concern regarding the future of physician-scientists, especially for those who combine patient care with clinical research, for at least 2 generations.13–19 This is magnified by the fact that the number of physicians actively engaged in research has recently declined, down to only 1.8% in 2003.20 For physicians performing research, there are 4 main pathways to becoming a successful faculty researcher: an extensive research experience during medical school (MD/PhD), an extensive research block in the middle of residency, an extensive research block during subspecialty fellowship training following residency, or “on the job training” while on faculty. Surgery is unique among medical specialties in being the only field to have a significant portion of its trainees perform postdoctoral fellowship in the middle of residency. Despite the persistence of this tradition in many academic medical centers and our pre hoc hypothesis that performing research during residency would lead to surgeons performing research in subsequent faculty positions, there are little data on the utility of this practice.

The success of surgical trainees in this study who performed research during their residency in obtaining funding following residency can be viewed in either a positive or negative light. Most trainees who applied for independent funding following graduation obtained it, with the majority receiving support from more than one source. In addition, the majority who applied for NIH funding received it. Specifically, 27 of 33 (82%) graduates who performed 2 to 3 years of research during residency obtained funding if they applied. In addition, 13 of 18 (72%) of graduates who performed research during residency obtained NIH funding if they applied and 5 of 9 (56%) obtained an R01. However, the majority of trainees never applied for funding of any type and only 5 graduates over a 15-year timeframe received an investigator initiated R01 from the NIH. Thus, looking at the data another way, only 27 of 65 graduates (41%) who performed 2 to 3 years of research during residency ever obtained independent funding, a substantially less impressive statistic. Similarly, only 13 of 65 graduates (20%) who performed research obtained NIH funding after residency, while only 5 of 65 (8%) received an R01. It is also important to note that the doubling of the NIH budget from 1998 to 2003 did not impact the number of graduates obtaining NIH funding. These results can therefore be looked at in a “glass is half full, glass is half empty” manner. On the one hand, those who choose to apply for funding of any type after residency are likely to be successful and the smaller percentage of those who apply for NIH funding are likely to be successful. On the other hand, this is a very select population (a subset of graduates of a residency program that already was self-selected by its academic nature), and the majority of graduates never apply for funding of any type with only a handful obtaining R01 funding.

This study suggests that predictive factors regarding the likelihood of successfully receiving grant support following residency can be identified prior to the conclusion of postgraduate training. Some of the predictors of ultimate external funding could possibly have been predicted in advance, ie, total number of papers and first author papers published during residency. Absolute numbers can be misleading since a single publication in a high-impact journal may be more meaningful than a number of manuscripts in lower-impact journals; however, on average, it is likely that researchers who are more productive are more likely to have success in obtaining grant support. Less predictable was the fact that the survey identified both applying for and receiving grant support during residency as an independent predictor of receiving external funding following residency. Applying for independent funding is not a requirement for performing resident research at Washington University, and we have no evidence that this is mandatory at other departments of surgery. It is impossible to know based upon the data presented whether the association between resident funding and faculty funding is causative or not. Most residents who apply for funding do so in their second clinical year of residency (8 months prior to entering the laboratory), and it is plausible that applicants who write a grant prior to entering the laboratory have an intellectual head start over their peers, which translates into greater productivity during the research years. It is also possible that this early exposure to grantsmanship is beneficial long-term in the ability to write and receive grants. However, it is equally plausible that those who write and/or receive grants during residency are more committed to research and are therefore more likely to be successful long-term. Interestingly, respondents (both academic and private practice) were only mildly enthusiastic about requiring all residents to apply for outside funding to support their laboratory time.

Only 2 predictors of NIH funding could be identified, likely because of the smaller sample size of surgeons with NIH funding. As with obtaining any external grant support, total number of papers from resident research predicted ultimate NIH funding. The total average number of years of research before and during residency was significantly higher (3.7) in NIH funded faculty researchers than those without NIH funding (2.8). Since the average length of time each group spent performing research during residency was similar, this means that it is not enough to look at resident research in isolation, but that total years of research prior to attainment of a faculty position is a more accurate assessment of one's potential to obtain external funding. This suggests that a self-selected group with extensive research experience is more likely to obtain funding, but it also implies that spending 1 to 3 years in surgical research in isolation is less likely to produce a bench researcher than it is to produce a clinical researcher, even if one performs basic science research during their residency. Of note, having a PhD prior to residency was not predictive of research success. There were 7 surgeons in this study with PhDs who have finished subspecialty fellowship training, and of these 2 did additional laboratory time during residency. A total of 3 of these received NIH funding (a number comparable to the overall success rate for MD/PhDs),20 but none converted this into R01 funding. We do not have an explanation for why no surgeon with an MD/PhD degree ended up with R01 funding, and it is difficult to make a conclusion from a sample size of 7. However, it will be important in the future to determine whether this represents an anomaly or if surgeons with MD/PhD degrees are less likely to convert their research training into R01s since our survey results are not in accordance with data demonstrating the number of R01s applications from physicians with MD/PhD degrees (regardless of medical specialty) has risen steadily over the past 15 years and the success rate for these applications is unchanged.20

Surgical trainees in a university-based residency are likely predisposed to an academic career, which is supported by our finding that most trainees took faculty positions after residency training, with the number of surgeons in academic positions unexpectedly slightly increasing over time. However, the influence of prior in-depth knowledge of research can be minimized somewhat by examining the 28 respondents who had no research experience before residency and the 13 respondents who had less than 1 year research experience before residency. These groups had a 35% and 46% chance, respectively, of obtaining external research funding following residency. This is similar to the 41% of all residents who spent 1 or more years of research prior to residency and 2 to 3 years of research during residency fellowship who ultimately obtained external funding. The success rate of faculty NIH funding in those with no research or less than 1 year of research prior to residency and 2 to 3 years of research during residency (18% and 23%, respectively) was slightly lower than those who performed 1 or more years of research prior to residency and 2 to 3 years of research during residency (29%). This is consistent with the data that total length of research time correlates to NIH funding. It should be noted that there are limited long-term data about what graduates of academic surgical programs do after residency. Although this was not the focus of this study, the ratio of graduates who ended up in academic versus private practice was somewhat surprising, although substantially higher than a previous study tracking the careers of graduates of the general surgery residency at UCLA from 1975 to 1990.10

The results of the opinion portion of the survey are potentially illuminating regarding the utility of performing research during surgical residency, regardless of one's ultimate career path. It was to be expected that academic surgeons felt that resident research was more valuable to their current career than private practitioners, and this was validated by the survey. However, both groups gave similarly high marks to the question “research was a worthwhile use of my time during residency.” The benefits to performing research during surgical residency are multifactorial: learning the scientific method, increased ability to critically review the literature, examining a specific problem in detail, less strenuous workload than the average work week of a surgery resident, ability to supplement income via moonlighting, etc. Although we cannot identify which of these elements were considered most beneficial, it is striking that nearly all respondents (academics and private practice) considered research a worthwhile portion of their residency, felt that surgery department resources are well used supporting 2 years of research for every resident, and felt that nearly 2 years was the appropriate length of time for an uncommitted resident to spend in laboratory research.

Our results suggest a broad definition of the practicing surgeon scientist. While 51 survey respondents currently perform research, this includes basic science, translational and clinical research. Some of this is funded in a peer reviewed fashion, and much is performed without external support. The time dedicated to research ranged from 2% to 75%, with an average of 26%. Not surprisingly, those with NIH funding had a high percentage of time committed to research (75% for K08s, variable for R01s). While the NIH-funded researcher may be considered the “gold standard” by many, our results indicate that most surgical researchers are not funded by the NIH, and, on average, approximately three fourths of their time is spent on clinical and administrative duties. This suggests a balance, whereby a small number of graduating surgeons from an academic program will perform traditional bench research and a large number will perform clinical research. If the “return on investment” for funding research during residency is the number of NIH funded surgical scientists, it is difficult to call the current model a success and difficult to make an argument that it is cost-effective. However, if the definition of surgeon scientist includes those who perform research in their professional lives (including those who receive no compensation but persist in their efforts regardless), then research performed during residency appears to lead to the development of a number of committed surgeon scientists. This interpretation suggests the current model of performing dedicated research time during residency is a valid method of training surgeon scientists, although one cannot conclude that it is superior or more cost-effective than performing research as part of fellowship training, as is common in other medical specialties.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Foremost among these is the lack of a control arm. Logistically, this is almost impossible to avoid since nearly all academic surgical residencies offer dedicated research years and a desire to perform research correlates with whether a surgeon ultimately goes into academics or private practice.9,10 While the self-selected nature of residents was unavoidable, the comparison of those with minimal or no research prior to residency to those with substantial prior research minimizes this variable as much as is feasible. As a single center study, it is also unclear how generalizable this is to other surgical programs. For instance, it is likely that the number and quality of a department's mentors plays a key role in the ultimate success of its trainees, and the high level of NIH funding in the parent institution surgery department may make these results difficult to replicate elsewhere. In addition, half of surgical residents who pursue dedicated research time during residency spend 1 year, and only 8% pursue 3 years.3 However, in this study, only 1% of respondents spent a single year in the laboratory and 33% spent greater than 2 years. Similarly, graduates of the program had a greater than 70% success rate when applying for NIH funding and a greater than 50% success rate when applying for R01s, numbers that exceed national averages. Of these, our data demonstrate that 53% (8 of 15) of NIH funded faculty members submitted RO1 applications and 63% (5 of 8) succeeded, for an overall conversion rate of 33% (5 of 15). This correlates very well with published data regarding K08 grants, where 61% of investigators submit an R01 application, of which 33% of the original grant recipients succeed.21

In addition, even though survey respondents and nonrespondents were not statistically different when retrospectively comparing percentages of surgeons in academics to private practice, we cannot rule out that those more likely to perform faculty research or those more favorable to research during residency disproportionately responded. Although there was an equal response rate among graduates regardless of graduation date, we did not take into account external pressures (such as changing medicare reimbursements) or external opportunities (such as the doubling of the NIH budget during the time period studied) in our analysis. These results also do not answer the question if performing research following residency as part of fellowship training as is frequently done in internal medicine subspecialties would be preferable to a situation where 3 to 7 years can pass between completing a postdoctoral research fellowship during general surgery residency and applying for external funding as a faculty member.

Despite these limitations, these data yield a number of insights regarding how performing 2 to 3 years of dedicated research during surgical residency impacts the development of the surgical scientist. The data indicate that in this single center, a majority of those who perform research during residency end up performing research as faculty members, and a large percentage end up funded through multiple mechanisms. Despite the fact that most surgeons perform basic science research during residency, they are more likely to perform clinical research as faculty members, and their likelihood of obtaining external funding can be predicted by productivity during residency, whether they apply for and/or receive grant support during residency, and the total years of research spent before and during residency. Further studies are needed to determine the generalizability of these results.

Footnotes

Supported by funding from National Institutes of Health (GM072808-01, GM66202, GM008795).

Reprints will not be available.

Address correspondence to Craig M. Coopersmith, MD, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8109, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: coopersmithc@wustl.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wells SA Jr. The surgical scientist. Ann Surg. 1996;224:239–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care: transfusion requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souba WW, Tanabe KK, Gadd MA, et al. Attitudes and opinions toward surgical research: a survey of surgical residents and their chairpersons. Ann Surg. 1996;223:377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Positions offered yearly through the National Resident Matching Program. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/res_match/tables/table1_05.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2006.

- 5.Stewart RD, Doyle J, Lollis SS, et al. Surgical resident research in New England. Arch Surg. 2000;135:439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RS, Debas HT. Research: a vital component of optimal patient care in the United States. Ann Surg. 2004;240:573–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangel SJ, Efron B, Moss RL. Recent trends in National Institutes of Health funding of surgical research. Ann Surg. 2002;236:277–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko CY, Whang EE, Longmire WP Jr, et al. Improving the surgeon's participation in research: is it a problem of training or priority? J Surg Res. 2000;91:5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn JC, Lai EC, Brooks CM, et al. The outcome of research training during surgical residency. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:362–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thakur A, Thakur V, Fonkalsrud EW, et al. The outcome of research training during surgical residency. J Surg Res. 2000;90:10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lessin MS, Klein MD. Does research during general surgery residency correlate with academic pursuits after pediatric surgery residency? J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1310–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NIH funding for departments of surgery in 2004. Available at: http://grants2.nih.gov/grants/award/rank/surgery04.htm. Accessed March 12, 2006.

- 13.Moore FD. The university in American surgery. Surgery. 1958;44:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung NS, Crowley WF Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289:1278–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyngaarden JB. The clinical investigator as an endangered species. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1254–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The clinical investigator: bewitched, bothered, and bewildered—but still beloved. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2803–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg LE. The physician-scientist: an essential—and fragile—link in the medical research chain. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1621–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JN, Moskowitz J. Preventing the extinction of the clinical research ecosystem. JAMA. 1997;278:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan DG. Clinical research: perceptions, reality, and proposed solutions: National Institutes of Health Director's Panel on Clinical Research. JAMA. 1998;280:1427–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ley TJ, Rosenberg LE. The physician-scientist career pipeline in 2005: build it, and they will come. JAMA. 2005;294:1343–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotchen TA, Lindquist T, Malik K, et al. NIH peer review of grant applications for clinical research. JAMA. 2004;291:836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]