Abstract

There is growing evidence for the intracellular role of cytokines and growth factors, but the pathways by which these activities occur remain largely obscure. Previous work from our laboratory identified the constitutive, aberrant expression of the 31-kDa IL-1α precursor (pre-IL-1α) in the nuclei of fibroblasts from the lesional skin of patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). We established that pre-IL-1α expression was associated with increased fibroblast proliferation and collagen production. Further investigation has led to the identification of a mechanism by which nuclear expression of pre-IL-1α affects fibroblast growth and matrix production. By using a yeast two-hybrid method, we found that pre-IL-1α binds necdin, a nuclear protein with growth suppressor activity. We mapped the region of pre-IL-1α responsible for necdin binding and found it to be localized near the N terminus, a region that is present on pre-IL-1α, but not the mature 17-kDa cytokine. Expression studies demonstrated that pre-IL-1α associates with necdin in the nuclei of mammalian cell lines and regulates cell growth and collagen expression. Our results provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, of a nuclear target for pre-IL-1α. Based on these findings, we propose that the constitutively up-regulated expression of pre-IL-1α in the nuclei of SSc fibroblasts up-regulates proliferation and matrix production of SSc fibroblasts through binding necdin, and by counteracting its effects on cell growth and collagen production.

IL-1α is a pleiotropic cytokine that has numerous effects on the growth and activation on a wide variety of cell types (1). Pre-IL-1α is the precursor of mature IL-1α containing a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in its N-terminal region. Processing of the 31-kDa pre-IL-1α to the 17-kDa mature form requires the membrane-associated cysteine proteases called calpains, and a variety of cells appear to be deficient in this processing (1). Several studies (2–8) indicate that pre-IL-1α accumulates as an intracellular precursor molecule with a molecular mass of 31-kDa in epithelial cells (keratinocytes) and some mesenchymal cells (i.e., endothelial cells and fibroblasts). Previous reports indicate that intracellular pre-IL-1α may serve as a regulator of cell growth, senescence, and differentiation (2–9) through an intracrine mechanism (10–16), through interaction with as yet unidentified intracellular target(s).

Fibrosis is one of the key features of systemic sclerosis (SSc), and is caused by increased proliferation and extracellular matrix production by fibroblasts of SSc patients (17, 18). In contrast to healthy adult human skin fibroblasts, SSc fibroblasts are resistant to the induction of quiescence by serum deprivation, continuing to synthesize DNA, and to express the immediate response protooncogene, c-myc (19). Previous reports (17–18, 20–24) have indicated that IL-1α increases fibroblast proliferation and collagen production. SSc fibroblasts constitutively express pre-IL-1α (2, 25), and the distribution of pre-IL-1α is predominantly intranuclear (Y. Kawaguchi and T.M.W., unpublished observation), whereas pre-IL-1α is not expressed in normal fibroblasts (2, 25). Although there is growing evidence in support of the intracellular biological activity of pre-IL-1α (2–16), the intracellular pathway through which pre-IL-1α exerts this effect is still unknown.

In this article, we identified an interaction of pre-IL-1α with the nuclear protein necdin (26, 27) in SSc fibroblasts by using yeast two-hybrid screening. We mapped the region of pre-IL-1α that is responsible for necdin binding. This interaction was confirmed in fibroblastic cell lines, and our findings indicate that pre-IL-1α antagonizes the growth inhibitory effect of necdin on Saos-2 cells, and attenuates the inhibitory effect of necdin on procollagen type I production. These results demonstrate that pre-IL-1α can exert its effect intracellularly by binding a nuclear protein in a pathway independent of its cell surface membrane receptors. Furthermore, these studies suggest a mechanism by which overexpression of pre-IL-1α stimulates proliferation and matrix production through binding necdin, and by counteracting its inhibitory effects on cell growth and collagen production.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture. Human dermal fibroblasts were derived from punch biopsies obtained from clinically affected and unaffected skin of SSc patients who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (formerly the American Rheumatism Association; Atlanta) preliminary classification criteria for systemic sclerosis (28), and also from their healthy identical twins. Primary cell cultures were established in 100-mm culture dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. At confluence, the fibroblasts were trypsinized and passaged. Cos-7 and Saos-2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Yeast Two-Hybrid System. Reagents for the yeast two-hybrid system were obtained from CLONTECH. Confluent fibroblasts in passages 4–5 from clinically affected or unaffected skin of an SSc patient were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h, followed by total RNA extraction by using the TRIzol reagent (GIBCO). Poly(A)+ RNA was prepared with PolyATtract system 1000 (Promega), and was used to generate cDNA. Activation domain (AD) fusion cDNA libraries in pGAD10 vector containing the AD (GAL4-AD) of yeast GAL4 transcription factor were constructed by following the manufacturer's protocol. The full-length cDNA of human pre-IL-1α was generated by RT-PCR from total RNA of SSc skin fibroblasts, and was cloned into plasmid pGBT9 to encode human pre-IL-1α fused with the binding domain GAL4-BD of yeast GAL4 transcription factor. The two-hybrid screening was performed by using host strain AH109 transformed with pGBT9:pre-IL-1α as bait. A mixture (1:1) of pGAD10-SSc affected and unaffected fibroblast cDNA libraries were used. His+ and Ade+ colonies were picked from the library screening plates (SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade) and tested for β-galactosidase activity by using the β-galactosidase colony-lift filter assay. Constructs of pGBT9 containing cDNAs encoding various lengths of the N terminus of IL-1α, the C terminus of IL-1α, pre-IL-1β, and IL-18 were generated by RT-PCR, followed by restriction enzyme digestion and ligation. Cotransformation of pGAD10:necdin-1 (one of the positive clones encoding potential pre-IL-1α-interacting proteins from two-hybrid screening) with one of the pGBT9 constructs containing one of the various inserts mentioned above was carried out on AH109 cells. The double transformants growing on SD/Leu and -Trp plates were replated on both SD/Leu and –Trp plates, and also on SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates. Colonies were lifted from SD/-Leu and -Trp plates on VWR grade 410 paper filters and were considered positive in the β-galactosidase colony-lift filter assay if they turned blue during a 3-h incubation at room temperature.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot. The full-length cDNA insert of human pre-IL-1α was generated from the pGBT9:preIL-1α vector and was subcloned into the expression vector pcDNA3. The cDNA encoding the mature form of IL-1α was amplified by PCR and was cloned into pcDNA3. The full-length cDNA insert of necdin was obtained from pGAD10:necdin-1 and subcloned into pFLAG-CMV vector. The pFLAG-CMV:necdin plasmid expressing necdin protein fused with the FLAG-tag was cotransfected with pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α into Cos-7 cells. The necdin gene with FLAG-tag was also subcloned into pcDNA3 vector and both pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin and pcDNA:pre-IL-1α were cotransfected into Saos-2 cells by using the calcium phosphate method (29). Nuclear extracts of Cos-7 or Saos-2 cells after 48 h of transfection were prepared (29). Cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/1.5 mM MgCl2/10 mM KCl/0.2 mM PMSF/0.5 mM DTT) and homogenized by a glass Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 3,300 × g for 15 min. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in the same buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl to extract nuclear proteins. The extracted material was sedimented at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants termed nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-M2-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. The antibody–protein complexes were adsorbed to protein G-Agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated proteins or total cell lysates of Saos-2 were analyzed by SDS/10% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti-IL-1α polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) by using the ECL-Western blotting detection system (Perkin–Elmer). In a parallel experiment, the nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-IL-1α polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz), resolved in SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-M2-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were visualized with the ECL-Western blotting detection system (Perkin–Elmer).

Immunostaining. Both Cos-7 and Saos-2 cells were grown on glass coverslips to 60–70% confluence, and were transfected with pcDNA3:preIL-1α or pFLAG-CMV:necdin expression vectors alone or in combination by using the calcium phosphate method. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized for 90 sec in 0.1% Triton X-100 or for 20 min in methanol. The cells were then dual-stained with rabbit anti-IL1α polyclonal antibody (Genzyme) followed by incubation with both Alexa Fluor-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes), and FITC-conjugated anti-M2-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes).

Cell Proliferation Assays. The colony formation assay was carried out as described (30). Saos-2 cells were grown to 70% confluence and were transfected with pcDNA3 alone (10 μg), pcDNA3:preIL-1α (5 μg), pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin (5 μg), or both pcDNA3:preIL-1α (5 μg) and pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin (5 μg) by the calcium phosphate method. The total amount of plasmids was adjusted to 10 μg per well by adding pcDNA3 vector lacking insert. G418 (500 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium 48 h after transfection and was kept for 21 days. The G418-resistant colonies were fixed with 10% acetate and 10% methanol for 15 min, and were visualized by staining with 0.4% crystal violet in 20% ethanol for 15 min. In parallel cultures, the G418-resistant colonies were harvested by gentle digestion with trypsin, and total cell numbers in each well were determined by counting directly with a hemocytometer. All cultures were carried out in triplicate, and each value represents the mean ± SD. For BrdUrd experiments, Saos-2 cells were transfected with pcDNA3, pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α, pcDNA3:Flag-necdin, or pcDNA3:IL-1α alone or in combination. G418 (500 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium 48 h after transfection and maintained for 14 days. Mixtures of the G418-resistant colonies for each experimental condition were seeded in 96-well plates at 4 × 104 cells per well, and proliferation was determined by BrdUrd incorporation by using the Biotrak cell proliferation ELISA system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The change in BrdUrd incorporation was calculated as the percentage of the value of control cells that were transfected with pcDNA3 alone.

Measurement of Procollagen Type I by ELISA. Saos-2 cells were grown to 70% conf luence, and were transfected with pcDNA3, pcDNA3:preIL-1α, pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin, or both pcDNA3:preIL-1α and pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin by the calcium phosphate method. G418 (500 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium 48 h after transfection and maintained for 21 days. Mixtures of the G418-resistant colonies for each experimental condition were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) with DMEM plus 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid. Five wells were used for each experimental condition. Supernatants were collected on day 3 and stored at –80°C. Cells were trypsinized and cell numbers were counted. Procollagen type I production of each culture supernatant was determined by a procollagen type I c-peptide ELISA kit (Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan). Each value represents the mean ± SD. (n = 5.)

Results

Identification of Potential pre-IL-1α-Binding Proteins by Two-Hybrid Screening in Yeast. To identify the proteins that associate with pre-IL-1α in the nucleus, and to mediate its direct intracellular effects in SSc fibroblasts, yeast two-hybrid screening was performed. Using pre-IL-1α as bait, we identified 23 cDNA clones that encoded potential pre-IL-1α-binding proteins by screening 2 × 106 independent colonies from the mixture (1:1) of SSc-affected and -unaffected fibroblast AD fusion libraries. Twenty-three colonies containing plasmids encoding potential pre-IL-1α-associated proteins grew on SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates, and all of them turned blue (positive) on the filters within 3 h in the β-galactosidase colony-lift filter assay. Because the lacZ gene in the AH109 yeast strain is regulated by a distinct GAL4-reponsive promoter, this result provides independent confirmation of the positive interaction between the pre-IL-1α bait and the GAL4-AD fusion proteins encoded by the plasmids from the fibroblast GAL4-AD fusion libraries.

A homology search of GenBank database revealed that 8 (from pGAD10:necdin-1 to pGAD10:necdin-8) of these 23 clones encoded a full-length nuclear protein known as necdin. Necdin was previously identified (30) as a cell growth suppressor in neural, osteosarcoma (Saos-2), and fibroblast cell lines, and may function through interaction with cell-cycle regulatory proteins such as simian virus 40 T antigen, E1A, E2F, or p53. Based on the facts that the SSc fibroblast AD fusion library was generated by using both oligo(dT) and random primers, and all of the eight necdin clones identified from the libraries encoded full-length necdin protein, we predicted the binding region of necdin to be within its N-terminal region.

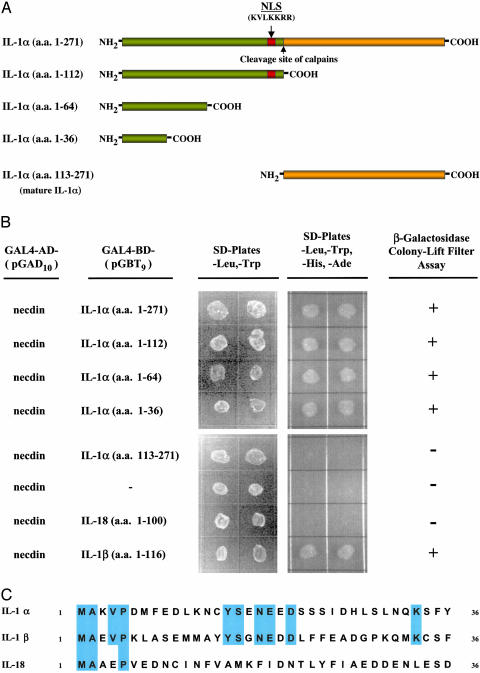

Mapping the Domain of pre-IL-1α That Interacts with Necdin. A schematic diagram of pre-IL-1α protein structure is shown in Fig. 1A. To identify the region of interaction with necdin, cDNAs encoding various lengths of the N-terminal region (amino acids 1–112, amino acids 1–64, or amino acids 1–36) and the C-terminal mature form (amino acids 113–271) of IL-1α were fused with the GAL4-binding domain of the pGBT9 vector, and were cotransformed with pGAD10:necdin-1 plasmid into AH109 cells. Double transformants were selected from SD/Leu and –Trp plates, and were replated on both SD/Leu and –Trp plates and SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates. Colonies were lifted from SD/Leu and –Trp plates, and were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. Our results localized the necdin-binding region of pre-IL-1α to the N terminus (amino acids 1–36). The C-terminal mature form of IL-1α and vector alone were negative on both SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates and β-galactosidase colony-lift filter assay (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Mapping of the pre-IL-1α domain that interacts with necdin in the yeast two-hybrid system. (A) Schematic diagram of the pre-IL-1α protein and its peptide fragments. NLS, nuclear localization sequence; calpains, cysteine proteases cleave pre-IL-1α at site indicated by the arrow to generate the mature form IL-1α. (B) Determination of necdinbinding domain in pre-IL-1α in the yeast two-hybrid system. cDNAs encoding full-length, N-terminal fragments of pre-IL-1α (amino acids 1–112, 1–64, and 1–36), the C-terminal mature form of IL-1α (amino acids 113–271), IL-18 (amino acids 1–100), and the N terminus of IL-1β (amino acids 1–116) were inserted in the plasmid vector pGBT9 and introduced into yeast AH109 cells along with the pGAD10:necdin-1 plasmid. The double transformants growing on SD/Leu and –Trp plates were replated on both SD/Leu and –Trp plates and SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates and were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. (C) Homology between the N-terminal region of pre-IL-1α (amino acids 1–36) and its family members.

The IL-1 cytokine family includes IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-18 (31, 32). IL-1α and IL-1β show only limited (26%) amino acid homology. There is no significant sequence homology between IL-1 and IL-18. IL-18 is designated as a member of the IL-1 family, because its receptor system and its signal transduction pathway are analogous to those of the IL-1 receptors. To determine whether the binding of necdin is specific to pre-IL-1α, the cDNAs of the N terminus of pre-IL-1β and IL-18 were inserted in pGAD10 vector, and were assayed in the yeast two-hybrid system. Interestingly, the N-terminal of pre-IL-1β also demonstrated positive binding with necdin on both SD/Leu, –Trp, –His, and –Ade plates and β-galactosidase colony-lift filter assay, but IL-18 was negative (Fig. 1B). The necdin-binding site of IL-1α was localized within the first 36 aa of the N terminus of IL-1α, a region of pre-IL-1α that shares high homology to the N terminus of IL-1β at amino acid level (Fig. 1C).

Necdin Binds pre-IL-1α in Transfected Mammalian Osteosarcoma and Fibroblastic Cells. To study the interaction between pre-IL-1α and necdin, we analyzed the association of these proteins in transfected mammalian cells. We prepared expression vectors that encoded a FLAG-tag fused to the N terminus of necdin (pCMV-FLAG:necdin and pcDNA3-FLAG:necdin), the full-length pre-IL-1α protein (pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α), and the mature (17 kDa) IL-1α protein (pcDNA3:IL-1α). These constructs were used to transiently transfect two mammalian cell lines: Saos-2 (a human osteoblastic sarcoma cell line) and COS-7 (a monkey kidney-derived fibroblast line).

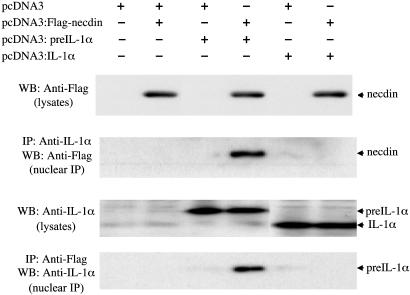

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis were performed on cell lysates and nuclear extracts from these transfected cells (Fig. 2). IL-1α was not detected in the total lysates of the Saos-2 cells that had been transfected with the pcDNA3 vector alone, or with the pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin vector. Lysates of the Saos-2 cells transfected with pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α alone, or together with the pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin vector demonstrated a single band on Western blot analysis that corresponded to the predicted 31-kDa size of pre-IL-1α. Analysis of lysates from cells transfected with the pcDNA3:IL-1α vector yielded an anti-IL-1α immunoreactive band with a Mr of 17 kDa, which was consistent with the mature form of IL-1α. Expression of FLAG-necdin and either pre-IL-1α or mature IL-1α did not affect the expression level of these proteins as judged by the signal intensity on Western blot. When nuclear extracts prepared from Saos-2 cells cotransfected with pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α and pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, the nuclear complexes contained a 31-kDa protein that reacted with anti-IL-1α antibody on Western blot (Fig. 2, lane 4). Similarly, when these nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-IL-1α antibody and analyzed by Western blot, they contained a 47-kDa protein that reacted with anti-FLAG antibody, which was consistent with FLAG-tagged necdin. In contrast, there was no association between necdin and the 17-kDa mature form of IL-1α, as determined by a failure to coimmunoprecipitate these proteins (Fig. 2, lane 6).

Fig. 2.

Association of pre-IL-1α with necdin in Saos-2 cells. The presence of necdin, pre-IL-1α, and IL-1α was analyzed in cell lysates and immunoprecipitates of nuclear extracts from transfected Saos-2 cells. Saos-2 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Total cell lysates (1 × 104 cells per lane, lysates) and nuclear immunoprecipitates (1 × 105 cells per lane, nuclear immunoprecipitation) were separated by SDS/10% PAGE, and were immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-IL-1α antibody, or with monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody.

These results were confirmed by using Cos-7 cells that were cotransfected with pCMV-FLAG:necdin and pcDNA3:preIL-1α (see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). Together, these results clearly indicate the association of pre-IL-1α with necdin in the nucleus of transfected mammalian osteosarcoma and fibroblast cell lines.

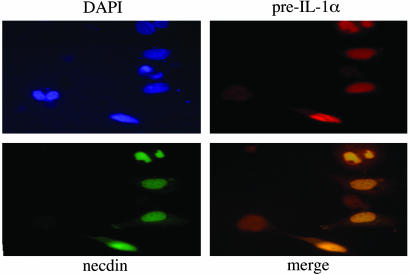

Colocalization of pre-IL-1α and Necdin in Mammalian Cell Lines. To establish colocalization of pre-IL-1α and necdin in the nuclei of cells, we performed dual staining of pre-IL-1α and necdin in cotransfected Saos-2 (Fig. 3) or Cos-7 cells (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The analysis of Saos-2 and Cos-7 cells transfected with pcDNA3::pre-IL-1α plasmid indicated that exogenously expressed pre-IL-1α was mainly localized in the nuclei. There was no difference in cell morphology between pcDNA3-transfected cells and pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α-transfected cells. Overexpressed FLAG-tagged necdin was also intensely stained in the nucleus. The cells were morphologically intact, suggesting that exogenous necdin had little or no effect on the viability of transfected cells. Dual immunostaining of pre-IL-1α and FLAG-tagged necdin in cells cotransfected with both expression vectors demonstrated colocalization of pre-IL-1α and necdin in the nuclei of transfected cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates colocalization of preIL-1α with necdin. Saos-2 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3:preIL-1α and pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin plasmids and stained with polyclonal anti-IL-1α antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (red) and FITC-conjugated monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (green). Nuclei were stained by DAPI (purple).

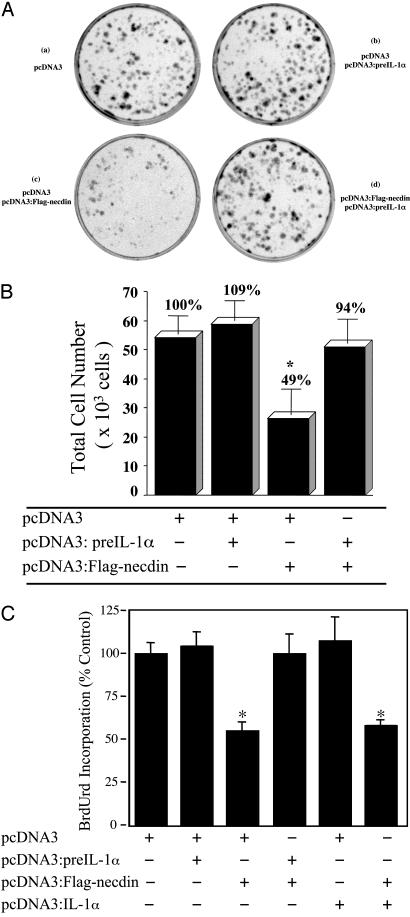

Association of pre-IL-1α with Necdin Counteracts the Growth Inhibitory Effect of Necdin on Saos-2 Cells. Necdin has been reported to induce growth suppression of transfected Saos-2 and NIH 3T3 cells (27, 33). We hypothesized that the association of pre-IL-1α, a stimulator of fibroblast proliferation, and necdin, a cell growth suppressor, would cause counteracting effects. To test whether the interaction between pre-IL-1α and necdin could affect the growth inhibitory effect of necdin, we coexpressed pre-IL-1α and necdin in Saos-2 cells, and performed colony formation assays (Fig. 4A). The cells were maintained in G418-containing medium for 21 days after transfection, and then colony formation was assessed. Transfection of Saos-2 cells with the pcDNA3::FLAG-necdin plasmid resulted in fewer G418-resistant colonies, and the size of these colonies was much smaller than that of the control plate with pcDNA3 vector alone. Overexpression of pre-IL-1α alone slightly increased colony numbers compared with those in the control plate, which might have occurred because it counteracted the effect of endogenous necdin in those cells. Expression of these two proteins in combination reversed the effect of necdin on reducing the number and the size of the colonies (Fig. 4A). To verify the results of the colony formation assay, the total cell numbers were determined in parallel cultures (Fig. 4B). Overexpression of pre-IL-1α increased cell number slightly (+9%), and overexpression of necdin decreased cell number significantly (–51%; P < 0.004). Coexpression of both proteins raised the cell number from 49% to 94% of control values.

Fig. 4.

Expression of pre-IL-1α reverses necdin-mediated growth suppression. (A) Colony formation analysis. Saos-2 cells were grown to 70% confluence and were transfected with the indicated plasmids. The G418-resistant colonies were visualized by staining with crystal violet. Each well is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Effect on cell number. In a parallel experiment, the G418-resistant colonies transfected with the indicated vectors were harvested by digestion with trypsin. Total cell number was counted directly with a hemocytometer. All cultures were carried out in triplicate, and each value represents the mean ± SD. (n = 3.) *, P < 0.004. (C) Effect on BrdUrd incorporation. Saos-2 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. After selection for 14 days, mixtures of the G418-resistant colonies for each experimental condition were seeded in 96-well plates, and proliferation was determined by BrdUrd incorporation. The values are expressed as percent of the control cultures transfected with pcDNA3 lacking insert. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. Each value represents the mean ± SD. (n = 4.) *, P < 0.0001.

In separate experiments, Saos-2 cells were stably transfected with pcDNA3, pcDNA3-FLAG:necdin, pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α, or pcDNA3:IL-1α, alone or in combination as indicated in Fig. 4C. The stably transfected lines were examined for the effects of expressing necdin ± pre-IL-1α or mature IL-1α on cell proliferation, as measured by BrdUrd incorporation. Similar to the effects on colony formation, necdin decreased BrdUrd incorporation in Saos-2 cells by ≈50% (P < 0.0001), and this effect was reversed by coexpression of pre-IL-1α. Expression of the mature form of IL-1α, however, did not reverse the inhibitory effect of necdin on proliferation (Fig. 4C).

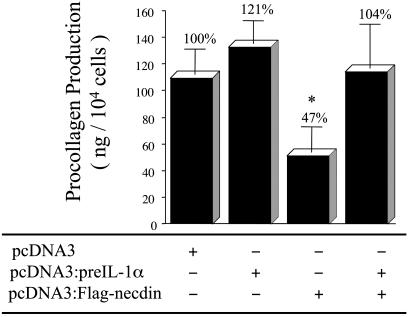

Expression of pre-IL-1α Blocks the Inhibitory Effect of Necdin on Procollagen Type I Production in Transfected Saos-2 Cells. Type I collagen is the major collagen synthesized by fibroblasts and Saos-2 cells. To determine the effects of necdin alone or in combination with pre-IL-1α on type I collagen synthesis, we analyzed procollagen production in the supernatants of transfected Saos-2 cells (Fig. 5). Procollagen production was increased in the supernatant of pre-IL-1α-transfected Saos-2 cells (+21%), and was decreased (–47%) in the supernatant of necdin-transfected cells. Coexpression of these two proteins attenuated the necdin-induced inhibitory effect on procollagen type I production in transfected Saos-2 cells.

Fig. 5.

Production of procollagen type I in transfected Saos-2 cells. Saos-2 cells were transfected with pcDNA3, pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α, pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin, or both pcDNA3:pre-IL-1α and pcDNA3:FLAG-necdin. Mixtures of the G418-resistant colonies for each experimental condition were reseeded in 24-well plates. Supernatants were collected on day 3, and procollagen type I production was determined by ELISA. Each value represents the mean ± SD. (n = 5.) *, P < 0.0007.

Discussion

The term “intracrine” has been used recently to describe the action of peptide hormones, growth factors, and cytokines within their cells of synthesis. In addition to acting as an autocrine and paracrine mediator of cell proliferation and differentiation, parathyroid hormone-related protein regulates nucleolar and/or ribosomal functions by directly interacting with RNA through an intracrine pathway (11, 16, 34). Hepatopoietin, a specifically hepatotropic growth factor, can directly trigger AP-1 pathway with a transcriptional coactivator through an intracrine mechanism (12). The 18-kDa form of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) binds to FGF receptor to act in an autocrine/paracrine manner, but high-Mr isoforms of FGF-2 containing an NLS are predominantly located in the nucleus, and are reported to be involved in cell proliferation and oncogenesis (13–15). IL-1α is demonstrated here to be capable of interacting with a nuclear target directly through a mechanism independent of cell surface receptors.

It has been noted that there is an absolute conservation of the NLS in the N terminus of all known IL-1α mammalian sequences, including sheep, cow, rabbit, rat, and mouse. It has been demonstrated that not only the N-terminal fragment of IL-1α but also pre-IL-1α containing the NLS can be translocated into nuclei of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, or transfected Cos-7 and NIH 3T3 cells (5, 8, 35). The 31-kDa pre-IL-1α has a complex intracellular distribution, including localization to microtubules, nucleus, cytosol, and the plasma membrane in a cell-type-specific manner (1). Posttranslational modification of the pre-IL-1α may contribute to its complex intracellular distribution. The pre-IL-1α molecules are subject to a number of posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, glycosylation, and myristylation, and all of posttranslational modifications are within the N-terminal region. The phosphorylation site (Ser-90) is adjacent to the NLS (amino acids 79–86). Myristylation takes place on Lys-82 and Lys-83 of pre-IL-1α, which is within the NLS of pre-IL-1α. The myristylation of this region causes loss of positive charges, and may regulate the activity of the NLS directly. There was no secreted 17-kDa mature form of IL-1α detectable in either immune-activated fibroblasts (36), or in the primary SSc fibroblasts that constitutively express pre-IL-1α (2, 25). We were unable to detect the C-terminal 17-kDa mature IL-1α in transfected Saos-2 cell lysates, nuclear extracts, and concentrated conditioned medium of stably expressing clones of Saos-2 cells (data not shown), which provides further evidence for the nuclear localization of pre-IL-1α. Our data suggest, therefore, that the intracellular pre-IL-1α generated endogenously in SSc fibroblasts (2) may activate the cells to promote the fibrosis of SSc without being secreted into the microenvironment.

Although a number of previous studies have demonstrated the intracellular localization and biologic role of intracellular IL-1α in various cell lines (2–9, 35, 36), no intracellular IL-1α-binding protein has been found. Our yeast two-hybrid screening revealed that more then one-third of the positive pre-IL-1α-binding clones encoded full-length necdin protein. Necdin is a cell-growth suppressor, and has function similar to that of tumor suppressor Rb (37). Necdin, itself may be a DNA-binding protein, because it shows tight binding on dsDNA affinity chromatography (38). Our results suggest that the binding site of necdin with IL-1α resides within the N-terminal region of necdin. The N-terminal region of necdin is proline-rich, which is a typical feature of the transactivation or transrepression domain of transcription factors (39, 40). The N-terminal truncated necdin (amino acids 110–325) exerted little or no growth suppression on Saos-2 cells (37). These data suggest that the counteracting effect of pre-IL-1α on the functions of necdin in Saos-2 cells could result from the association of these two proteins that prevents the direct binding of necdin to DNA or other transcription factors.

The biological activity of the N-terminal “propiece” of pre-IL-1α was previously investigated in glomerular mesangial cells (35). Overexpression of the N-terminal propiece (amino acids 1–112) in glomerular mesangial cells rendered these cells capable of growth in soft agar and yielded tumor formation in athymic nu/nu mice. The biologic role of the N-terminal propiece was independent of the pathways involving the plasma membrane receptor-bound C-terminal mature IL-1α, but the mechanism was unknown. Our two-hybrid mapping data for the association of pre-IL-1α/necdin suggests that the biologic activity of pre-IL-1α in transfected Saos-2 cells could be N-terminal-specific, and that oncogenic activity of the N-terminal pre-IL-1α may result from the interaction of pre-IL-1α with necdin. This finding is consistent with our data demonstrating that only pre-IL-1α forms a complex with necdin in Saos-2 cells (Fig. 2), and only pre-IL-1α reversed the growth inhibitory effect of necdin (Fig. 4). On the other hand, our yeast two-hybrid data also demonstrated that the N terminus of IL-1β was capable of interacting with necdin. To date there is no evidence in support of an intracellular role for pre-IL-1β or its N-terminal fragment, which is released by caspase 1/ICE (1). It remains to be determined if and how the N-terminal fragment of IL-1β is translocated to the nucleus, because it lacks the NLS present in pre-IL-1α at amino acids 79–85.

Necdin is abundantly expressed in most human tissues (41), and Northern blot results (data not shown) revealed that necdin mRNA is abundantly expressed in primary dermal fibroblasts, including fibroblast lines from SSc patients and healthy controls (identical twins discordant for SSc; see Materials and Methods for details). Our findings in Saos-2 cells indicated that pre-IL-1α antagonized the growth inhibitory activity of necdin, and reversed its inhibition of type I collagen expression. It is likely that the effects of pre-IL-1α on proliferation and collagen expression in SSc dermal fibroblasts would be similar, because they constitutively express necdin. Together, these results provide further insight into the potential pathogenesis of SSc, in which fibrosis is associated with increased proliferation, type I collagen overproduction, and the aberrant expression of pre-IL-1α in dermal fibroblasts (2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scleroderma Research Fund (Boston) and National Institutes of Health Grant AR-44266.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: SSc, systemic sclerosis; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; AD, activation domain; pre-IL-1α, precursor to mature IL-1α.

References

- 1.Dinarello, C. A. (1996) Blood 87, 2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawaguchi, Y., Hara, M. & Wright, T. M. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1253–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupper, T. S. (1990) J. Invest. Dermatol. 94, 146S–150S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groves, R. W., Mizutani, H., Kieffer, J. D. & Kupper, T. S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11874–11878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wessendorf, J. H., Garfinkel, S., Zhan, X., Brown, S. & Maciag, T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 22100–22104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson, F. T., Torrano, F., Locksley, R. M. & Lovett, D. H. (1992) J. Cell Physiol. 152, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosley, B., Urdal, D. L., Prickett, K. S., Larsen, A., Cosman, D., Conlon, P. J., Gillis, S. & Dower, S. K. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 2941–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier, J. A., Statuto, M. & Ragnotti, G. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1845–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maier, J. A., Voulalas, P., Roeder, D. & Maciag, T. (1990) Science 249, 1570–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Re, R. (1999) Hypertension 34, 534–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarts, M. M., Levy, D., He, B., Stregger, S., Chen, T., Richard, S. & Henderson, J. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4832–4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu, C., Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Xing, G., Tang, F., Wang, Q., Sun, Y., Wei, H., Yang, X., Wu, C., et al. (2002) FASEB J. 16, 90–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van den Berghe, L., Laurell, H., Huez, I., Zanibellato, C., Prats, H. & Bugler, B. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1709–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delrieu, I. (2000) FEBS Lett. 468, 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada-Ban, M., Thiery, J. P. & Jouanneau, J. (2000) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 32, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gujral, A., Burton, D. W., Terkeltaub, R. & Deftos, L. J. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 2282–2288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furst, D. E. & Clements, P. J. (1997) J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 48, 53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeRoy, E. C. (1992) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51, 286–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trojanowska, M., Wu, L. T. & LeRoy, E. C. (1988) Oncogene 3, 477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strieter, R. (2001) Chest 120, Suppl. 1, 77S–85S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahari, V. M., Heino, J. & Vuorio, E. (1987) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 929, 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postlethwaite, A. E., Raghow, R., Stricklin, G. P., Poppleton, H., Seyer, J. M. & Kang, A. H. (1988) J. Cell Biol. 106, 311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldring, M. B. & Krane, S. M. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 16724–16729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raines, E. W., Dower, S. K. & Ross, R. (1989) Science 243, 393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawaguchi, Y. (1994) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 97, 445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maruyama, K., Usami, M., Aizawa, T. & Yoshikawa, K. (1991) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 178, 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshikawa, K. (2000) Neurosci. Res. 37, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subcommittee for Scleroderma Criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. (1980) Arthritis Rheum. 23, 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A. & Struhl, K. (1995) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Wiley, New York).

- 30.Taniura, H., Matsumoto, K. & Yoshikawa, K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16242–16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishida, T., Nishino, N., Takano, M., Kawai, K., Bando, K., Masui, Y., Nakai, S. & Hirai, Y. (1987) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 143, 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akira, S. (2000) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi, Y., Matsuyama, K., Takagi, K., Sugiura, H. & Yoshikawa, K. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213, 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam, M. H., House, C. M., Tiganis, T., Mitchelhill, K. I., Sarcevic, B., Cures, A., Ramsay, R., Kemp, B. E., Martin, T. J. & Gillespie, M. T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18559–18566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevenson, F. T., Turck, J., Locksley, R. M. & Lovett, D. H. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huleihel, M., Douvdevani, A., Segal, S. & Apte, R. N. (1990) Eur. J. Immunol. 20, 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taniura, H., Taniguchi, N., Hara, M. & Yoshikawa, K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maruyama, E. (1996) Biochem. J. 314, 895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Caestecker, M. P., Yahata, T., Wang, D., Parks, W. T., Huang, S., Hill, C. S., Shioda, T., Roberts, A. B. & Lechleider, R. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2115–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu, J., Zhang, S., Jiang, J. & Chen, X. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39927–39934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jay, P., Rougeulle, C., Massacrier, A., Moncla, A., Mattei, M. G., Malzac, P., Roeckel, N., Taviaux, S., Lefranc, J. L., Cau, P., et al. (1997) Nat. Genet. 17, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.