Abstract

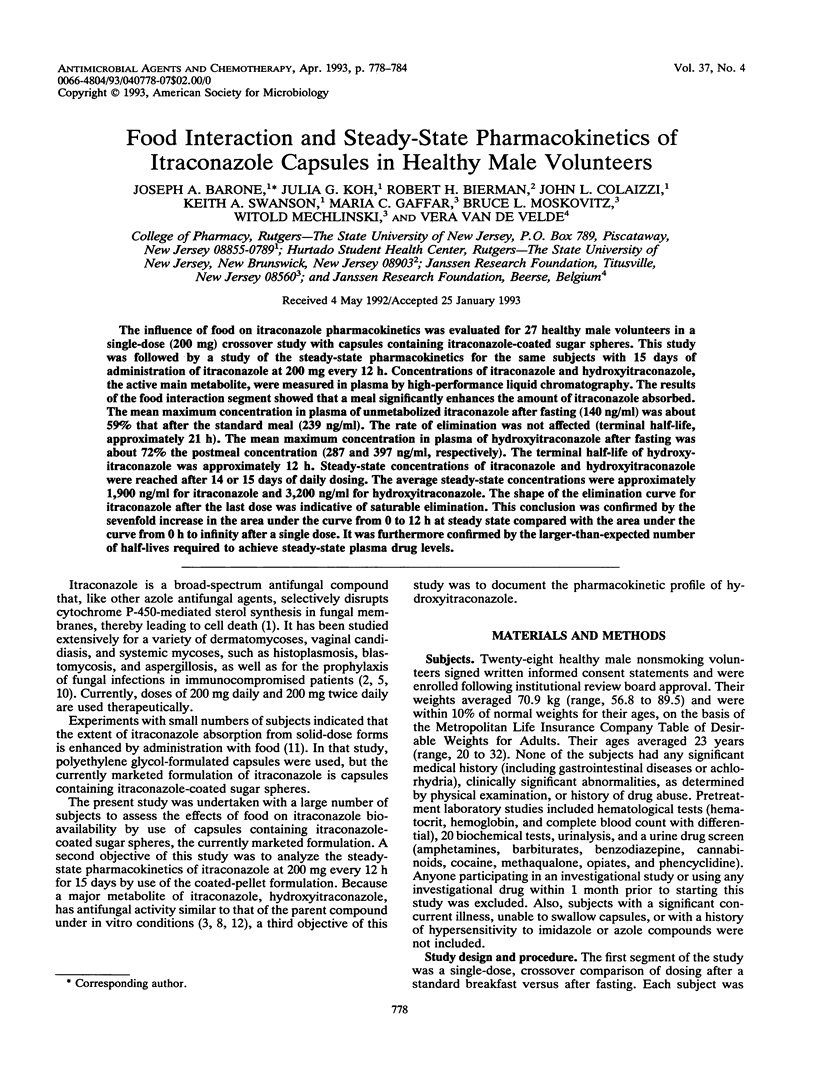

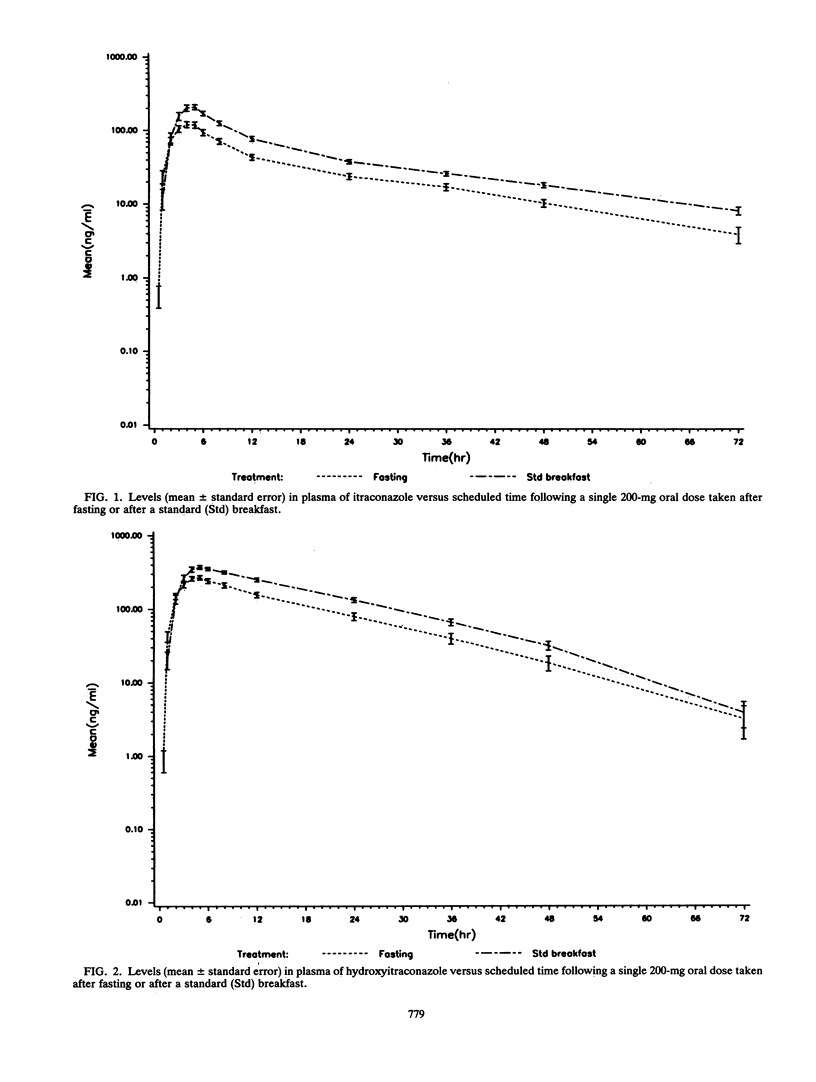

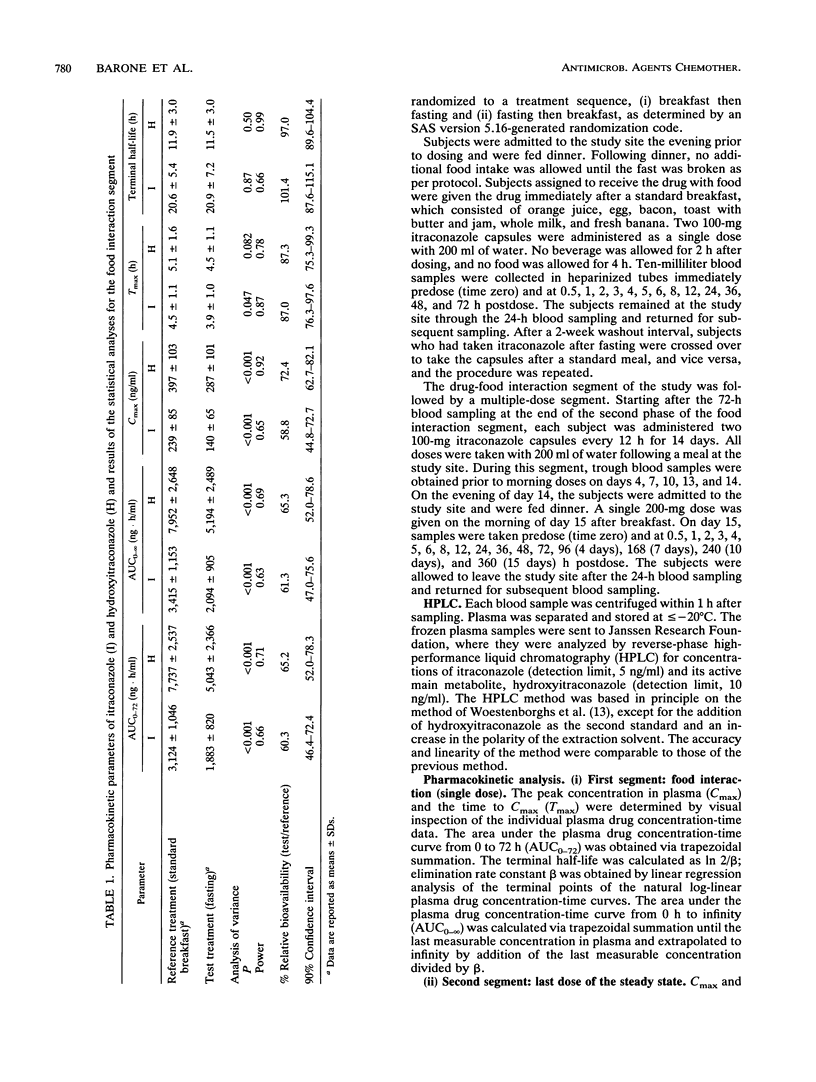

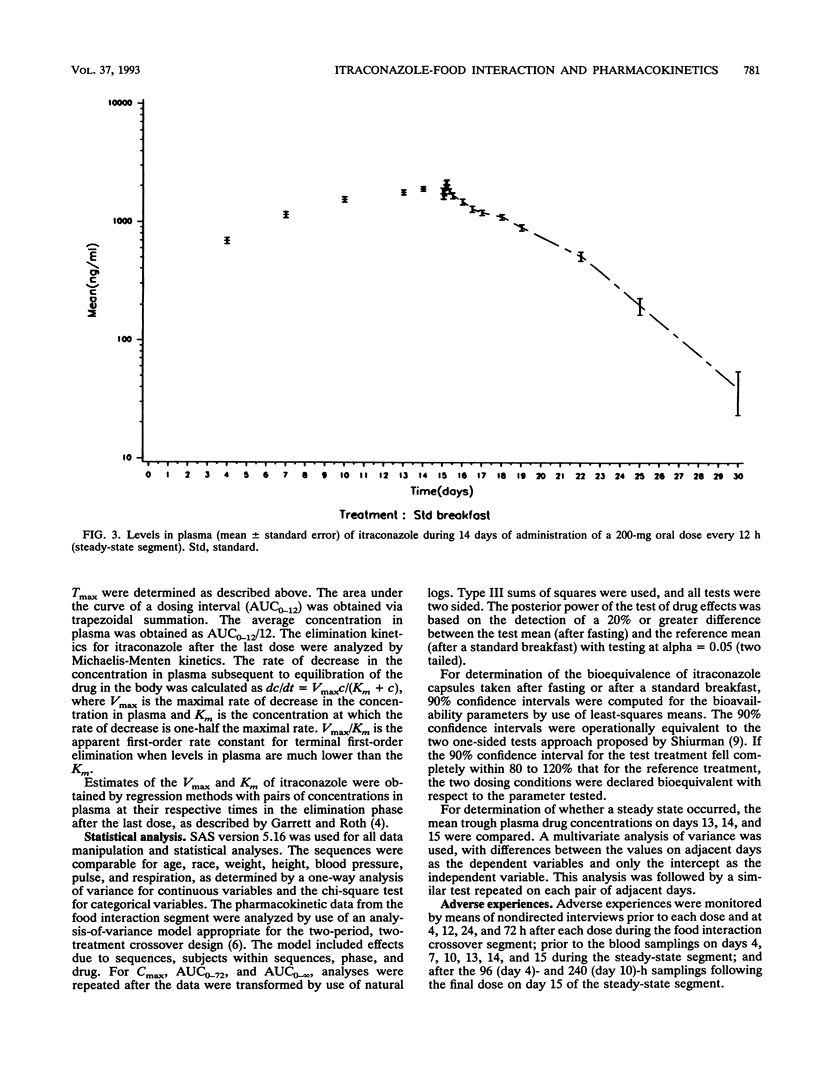

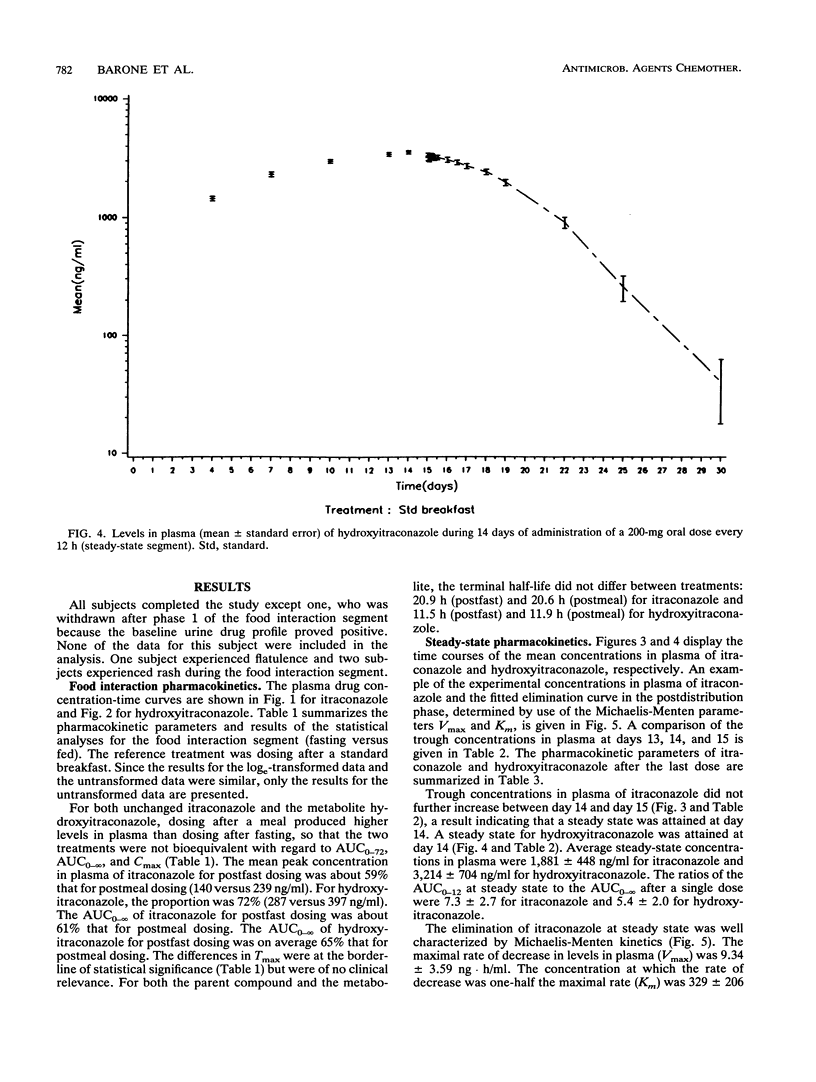

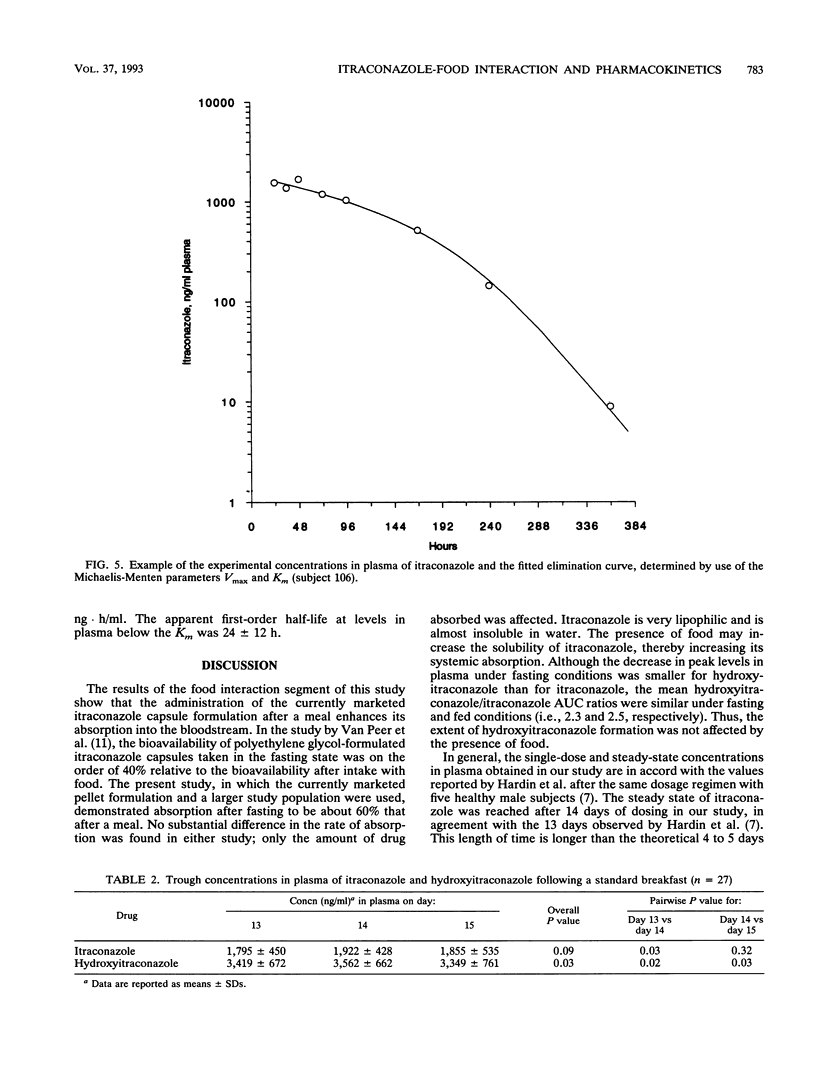

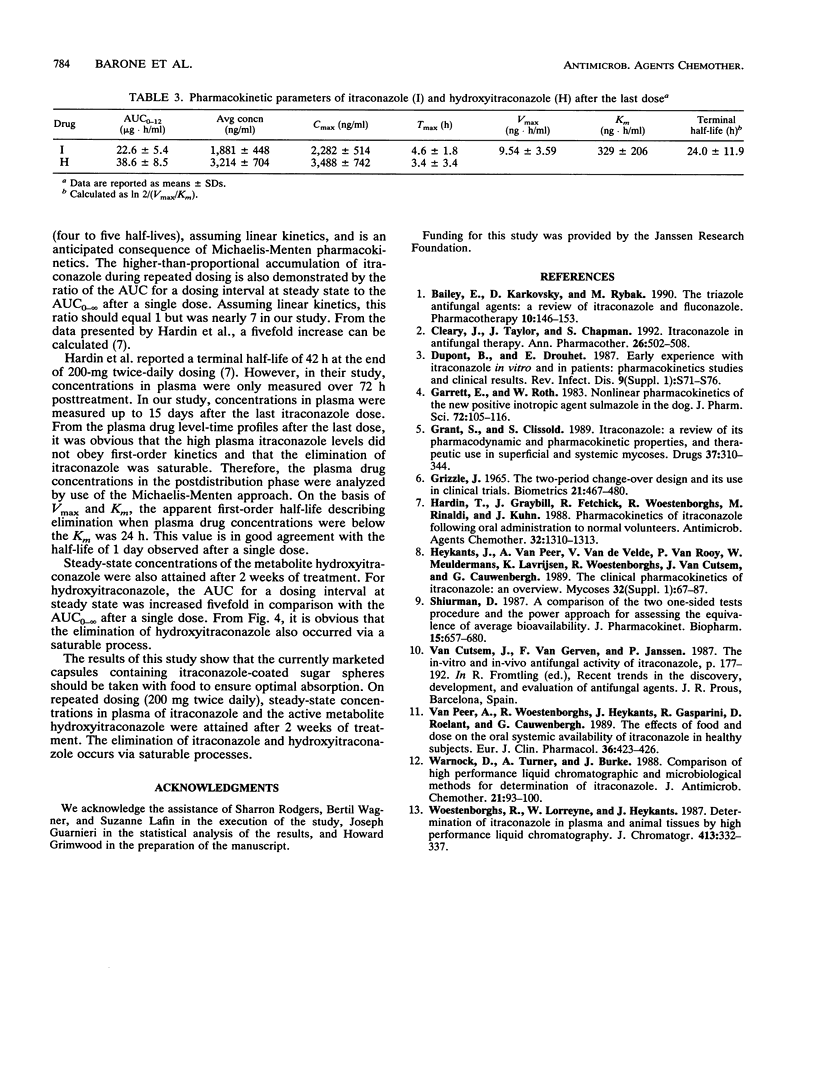

The influence of food on itraconazole pharmacokinetics was evaluated for 27 healthy male volunteers in a single-dose (200 mg) crossover study with capsules containing itraconazole-coated sugar spheres. This study was followed by a study of the steady-state pharmacokinetics for the same subjects with 15 days of administration of itraconazole at 200 mg every 12 h. Concentrations of itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole, the active main metabolite, were measured in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. The results of the food interaction segment showed that a meal significantly enhances the amount of itraconazole absorbed. The mean maximum concentration in plasma of unmetabolized itraconazole after fasting (140 ng/ml) was about 59% that after the standard meal (239 ng/ml). The rate of elimination was not affected (terminal half-life, approximately 21 h). The mean maximum concentration in plasma of hydroxyitraconazole after fasting was about 72% the postmeal concentration (287 and 397 ng/ml, respectively). The terminal half-life of hydroxyitraconazole was approximately 12 h. Steady-state concentrations of itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole were reached after 14 or 15 days of daily dosing. The average steady-state concentrations were approximately 1,900 ng/ml for itraconazole and 3,200 ng/ml for hydroxyitraconazole. The shape of the elimination curve for itraconazole after the last dose was indicative of saturable elimination. This conclusion was confirmed by the sevenfold increase in the area under the curve from 0 to 12 h at steady state compared with the area under the curve from 0 h to infinity after a single dose. It was furthermore confirmed by the larger-than-expected number of half-lives required to achieve steady-state plasma drug levels.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bailey E. M., Krakovsky D. J., Rybak M. J. The triazole antifungal agents: a review of itraconazole and fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10(2):146–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary J. D., Taylor J. W., Chapman S. W. Itraconazole in antifungal therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1992 Apr;26(4):502–509. doi: 10.1177/106002809202600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont B., Drouhet E. Early experience with itraconazole in vitro and in patients: pharmacokinetic studies and clinical results. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Jan-Feb;9 (Suppl 1):S71–S76. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_1.s71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIZZLE J. E. THE TWO-PERIOD CHANGE-OVER DESIGN AN ITS USE IN CLINICAL TRIALS. Biometrics. 1965 Jun;21:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett E. R., Roth W. Nonlinear pharmacokinetics of the new positive inotropic agent sulmazole in the dog. J Pharm Sci. 1983 Feb;72(2):105–116. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600720203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S. M., Clissold S. P. Itraconazole. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs. 1989 Mar;37(3):310–344. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198937030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin T. C., Graybill J. R., Fetchick R., Woestenborghs R., Rinaldi M. G., Kuhn J. G. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole following oral administration to normal volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Sep;32(9):1310–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heykants J., Van Peer A., Van de Velde V., Van Rooy P., Meuldermans W., Lavrijsen K., Woestenborghs R., Van Cutsem J., Cauwenbergh G. The clinical pharmacokinetics of itraconazole: an overview. Mycoses. 1989;32 (Suppl 1):67–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuirmann D. J. A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987 Dec;15(6):657–680. doi: 10.1007/BF01068419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Peer A., Woestenborghs R., Heykants J., Gasparini R., Gauwenbergh G. The effects of food and dose on the oral systemic availability of itraconazole in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36(4):423–426. doi: 10.1007/BF00558308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock D. W., Turner A., Burke J. Comparison of high performance liquid chromatographic and microbiological methods for determination of itraconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jan;21(1):93–100. doi: 10.1093/jac/21.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woestenborghs R., Lorreyne W., Heykants J. Determination of itraconazole in plasma and animal tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1987 Jan 23;413:332–337. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(87)80249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]