Abstract

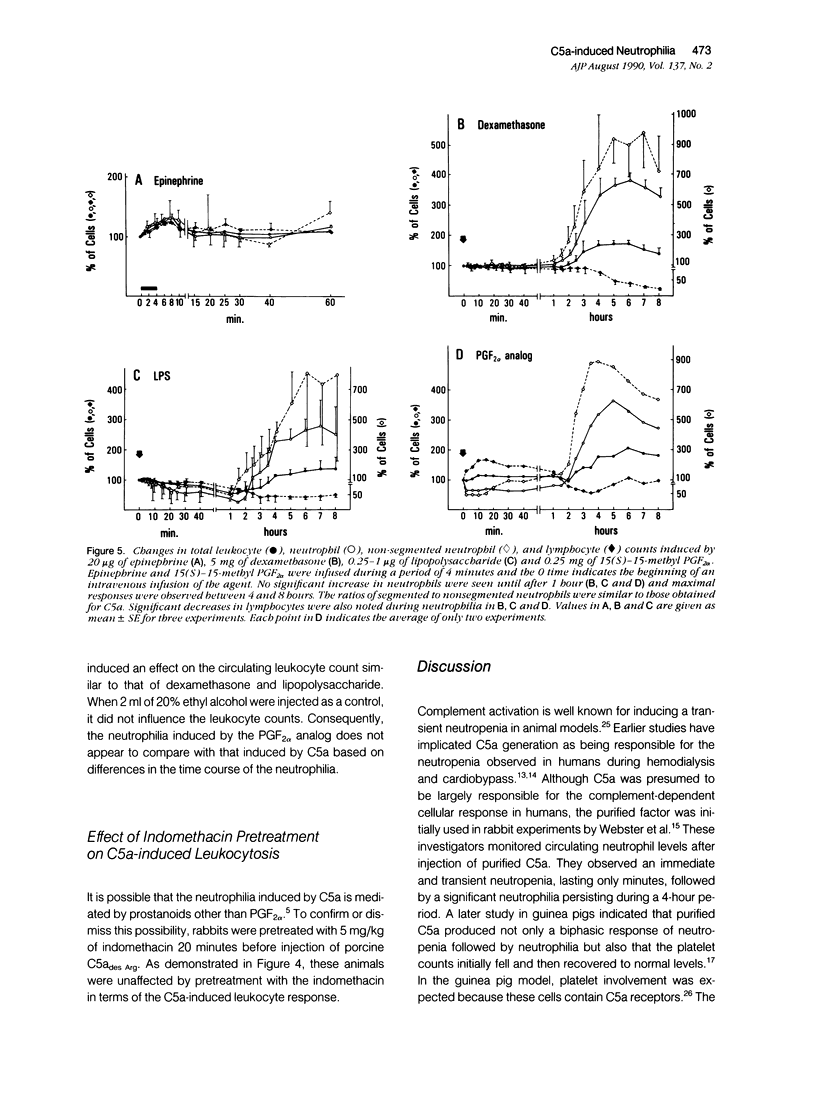

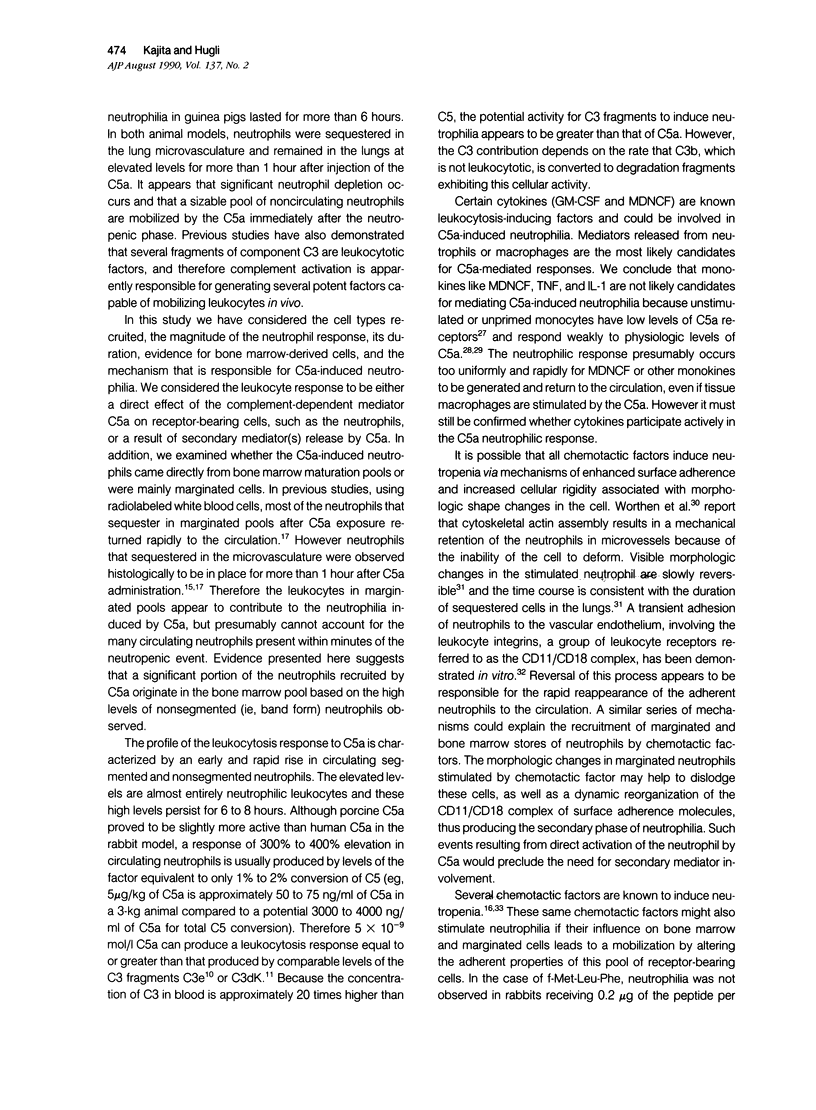

The leukocytosis activity of C5a was studied in a rabbit model. Blood samples were drawn for cell counts through a catheter placed in an artery of one rabbit ear after injection of either porcine or human C5a into a vein in the opposite ear. These studies indicate the potential of C5a to mobilize bone marrow neutrophils following transient C5a-induced neutropenia, based on counts of nonsegmented neutrophils. The numbers of circulating neutrophils can be selectively elevated by 300% to 400%, within 1 to 2 hours, in rabbits given only microgram quantities (1 to 5 x 10(-9) mol/l) of C5a or C5adesArg. These quantities of C5a are equivalent to 1% to 2% of complement C5 activation. The time-course of the induced neutrophilia is characteristic of C5a, increasing rapidly in the first 10 to 20 minutes after injection and attaining a maximum level at 2 to 5 hours, then decreasing slowly to normal levels over the next 4 to 6 hours. After boiling at 100 degrees C for 10 minutes, C5a (C5ades Arg) lost its leukocytosis activity, indicating that the cellular effect was not caused by endotoxin. Other known leukocytosis factors, such as epinephrine, dexamethasone, lipopolysaccharide, and the prostanoid 15(S)-15-methyl PGF2 alpha, produced a distinctly different profile of leukocyte mobilization than that of C5a. The C5a-induced neutrophilia was not inhibited by pretreating these animals with indomethacin, suggesting that it is not a prostanoid-induced effect. One hypothesis is that no secondary cellular mediator system is involved in C5a-mediated leukocytosis, but rather than C5a alone is responsible for a rapid mobilization of neutrophils from bone marrow pools, and perhaps marginated pools, following neutropenia. Circulating neutrophils are activated by C5a and thereby become deformed and adherent, leading to a neutropenia, sequestration, and depletion of cells. After the neutropenic event an immediate neutrophilic response is required for replacement of this particular cell population and to re-establish homeostasis. Therefore the role of C5a may be just as important as other known leukocytosis factors (fragments from C3, for example) in promoting complement-dependent neutrophil mobilization in response to tissue injury, infections, or extracorporeal blood treatments.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ATHENS J. W., HAAB O. P., RAAB S. O., MAUER A. M., ASHENBRUCKER H., CARTWRIGHT G. E., WINTROBE M. M. Leukokinetic studies. IV. The total blood, circulating and marginal granulocyte pools and the granulocyte turnover rate in normal subjects. J Clin Invest. 1961 Jun;40:989–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI104338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend W. P., Massoni R. J., Niemann M. A., Giclas P. C. Absence of induction of IL-1 production in human monocytes by complement fragments. J Immunol. 1989 Jan 1;142(1):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C. R., Athens J. W., Boggs D. R., Warner H. R., Cartwright G. E., Wintrobe M. M. Leukokinetic studies. 13. A non-steady-state kinetic evaluation of the mechanism of cortisone-induced granulocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1968 Feb;47(2):249–260. doi: 10.1172/JCI105721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs D. R., Cartwright G. E., Wintrobe M. M. Neutrophilia-inducing activity in plasma of dogs recovering from drug-induced myelotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 1966 Jul;211(1):51–60. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.211.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs D. R., Marsh J. C., Chervenick P. A., Cartwright G. E., Wintrobe M. M. Neutrophil releasing activity in plasma of normal human subjects injected with endotoxin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1968 Mar;127(3):689–693. doi: 10.3181/00379727-127-32774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker L. H., Nolph K. D. Mechanisms of recovery from neutropenia induced by hemodialysis. Blood. 1971 Nov;38(5):623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin N. C., Hugli T. E. The primary structure of porcine C3a anaphylatoxin. J Immunol. 1976 Sep;117(3):990–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock P. R., Fehr J., Dalmasso A. P., Brighan K. L., Jacob H. S. Hemodialysis leukopenia. Pulmonary vascular leukostasis resulting from complement activation by dialyzer cellophane membranes. J Clin Invest. 1977 May;59(5):879–888. doi: 10.1172/JCI108710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue R. E., Wang E. A., Stone D. K., Kamen R., Wong G. G., Sehgal P. K., Nathan D. G., Clark S. C. Stimulation of haematopoiesis in primates by continuous infusion of recombinant human GM-CSF. 1986 Jun 26-Jul 2Nature. 321(6073):872–875. doi: 10.1038/321872a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez H. N., Hugli T. E. Partial characterization of human C5a anaphylatoxin. I. Chemical description of the carbohydrate and polypeptide prtions of human C5a. J Immunol. 1976 Nov;117(5 Pt 1):1688–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka Y., Nielsen L. P., Hugli T. E. Characterization of receptors to the anaphylatoxins on isolated cells. Dermatologica. 1989;179 (Suppl 1):35–40. doi: 10.1159/000248446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardinali M., Circardi M., Agostoni A., Hugli T. E. Complement activation in extracorporeal circulation: physiological and pathological implications. Pathol Immunopathol Res. 1986;5(3-5):352–370. doi: 10.1159/000157026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardinali M., Hugli T. E., Ward D. M., Agostoni A. PMN C5a-receptor down regulation is not involved in recovery from C5a-induced neutropenia. ASAIO Trans. 1987 Jul-Sep;33(3):482–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard C., Hugli T. E. Anaphylatoxin from the fifth component of porcine complement. Purification and partial chemical characterization. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jul 25;254(14):6346–6351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B., Müller-Eberhard H. J. C3e: an acidic fragment of human C3 with leukocytosis-inducing activity. J Immunol. 1979 Aug;123(2):616–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt D. E., Weaver L. J., Hudson L. D., Craddock P. R., Jacob H. S. Association of complement activation and elevated plasma-C5a with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Pathophysiological relevance and possible prognostic value. Lancet. 1980 May 3;1(8175):947–949. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeprich P. D., Jr, Dahinden C. A., Lachmann P. J., Davis A. E., 3rd, Hugli T. E. A synthetic nonapeptide corresponding to the NH2-terminal sequence of C3d-K causes leukocytosis in rabbits. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 10;260(5):2597–2600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T., Böttger E. C., Baum H. P., Dennebaum R., Hadding U., Bitter-Suermann D. Evaluation of low dose anaphylatoxic peptides in the pathogenesis of the adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Monitoring of early C5a effects in a guinea-pig in vivo model after i.v. application. Eur J Clin Invest. 1986 Dec;16(6):500–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1986.tb02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugli T. E., Gerard C., Kawahara M., Scheetz M. E., 2nd, Barton R., Briggs S., Koppel G., Russell S. Isolation of three separate anaphylatoxins from complement-activated human serum. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981 Dec 4;41:59–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00225297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce R. A., Boggs D. R., Hasiba U., Srodes C. H. Marginal neutrophil pool size in normal subjects and neutropenic patients as measured by epinephrine infusion. J Lab Clin Med. 1976 Oct;88(4):614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuze J. E., Baker M. D., Oakes A. L., Baehner R. L. Comparison of in vivo effects of intravenous infusion of N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine and phorbol myristate acetate in rabbits. Inflammation. 1987 Dec;11(4):481–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00915990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo S. K., Detmers P. A., Levin S. M., Wright S. D. Transient adhesion of neutrophils to endothelium. J Exp Med. 1989 May 1;169(5):1779–1793. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg C., Marceau F., Hugli T. E. C5a-induced hemodynamic and hematologic changes in the rabbit. Role of cyclooxygenase products and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Am J Pathol. 1987 Sep;128(3):471–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENKIN V. The determination of the level of leukocytes in the blood stream with inflammation; a thermostable component concerned in the mechanism of leukocytosis. Blood. 1949 Dec;4(12):1323–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P., Lam C., Obenaus H., Liehl E., Besemer J. Recombinant human GM-CSF induces leukocytosis and activates peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils in nonhuman primates. Blood. 1987 Jul;70(1):206–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuth J. L., Morgan E. L., DiSipio R. G., Hugli T. E. Suppression of T lymphocyte functions by human C3 fragments. I. Inhibition of human T cell proliferative responses by a kallikrein cleavage fragment of human iC3b. J Immunol. 1983 Jun;130(6):2605–2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbacher J., Rosenfeld S. I., MacPherson J. L., Thiem P. A., Leddy J. P. Nylon fiber leukapheresis: associated complement component changes and cranulocytopenia. Blood. 1978 Feb;51(2):359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rother K. Leucocyte mobilizing factor: a new biological activity derived from the third component of complement. Eur J Immunol. 1972 Dec;2(6):550–558. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830020615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields J. M., Haston W. S. Behaviour of neutrophil leucocytes in uniform concentrations of chemotactic factors: contraction waves, cell polarity and persistence. J Cell Sci. 1985 Mar;74:75–93. doi: 10.1242/jcs.74.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulich T. R., Dakay E. B., Williams J. H., Ni R. X. In vivo induction of neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and diminution of neutrophil adhesion by stable analogs of prostaglandins E1, E2, and F2 alpha. Am J Pathol. 1986 Jul;124(1):53–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulich T. R., Keys M., Ni R. X., del Castillo J., Dakay E. B. The contributions of adrenal hormones, hemodynamic factors, and the endotoxin-related stress reaction to stable prostaglandin analog-induced peripheral lymphopenia and neutrophilia. J Leukoc Biol. 1988 Jan;43(1):5–10. doi: 10.1002/jlb.43.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme J., Van Beeumen J., Opdenakker G., Billiau A. A novel, NH2-terminal sequence-characterized human monokine possessing neutrophil chemotactic, skin-reactive, and granulocytosis-promoting activity. J Exp Med. 1988 Apr 1;167(4):1364–1376. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R. O., Larsen G. L., Mitchell B. C., Goins A. J., Henson P. M. Absence of inflammatory lung injury in rabbits challenged intravascularly with complement-derived chemotactic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982 Mar;125(3):335–340. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen G. S., Schwab B., 3rd, Elson E. L., Downey G. P. Mechanics of stimulated neutrophils: cell stiffening induces retention in capillaries. Science. 1989 Jul 14;245(4914):183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2749255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]