Abstract

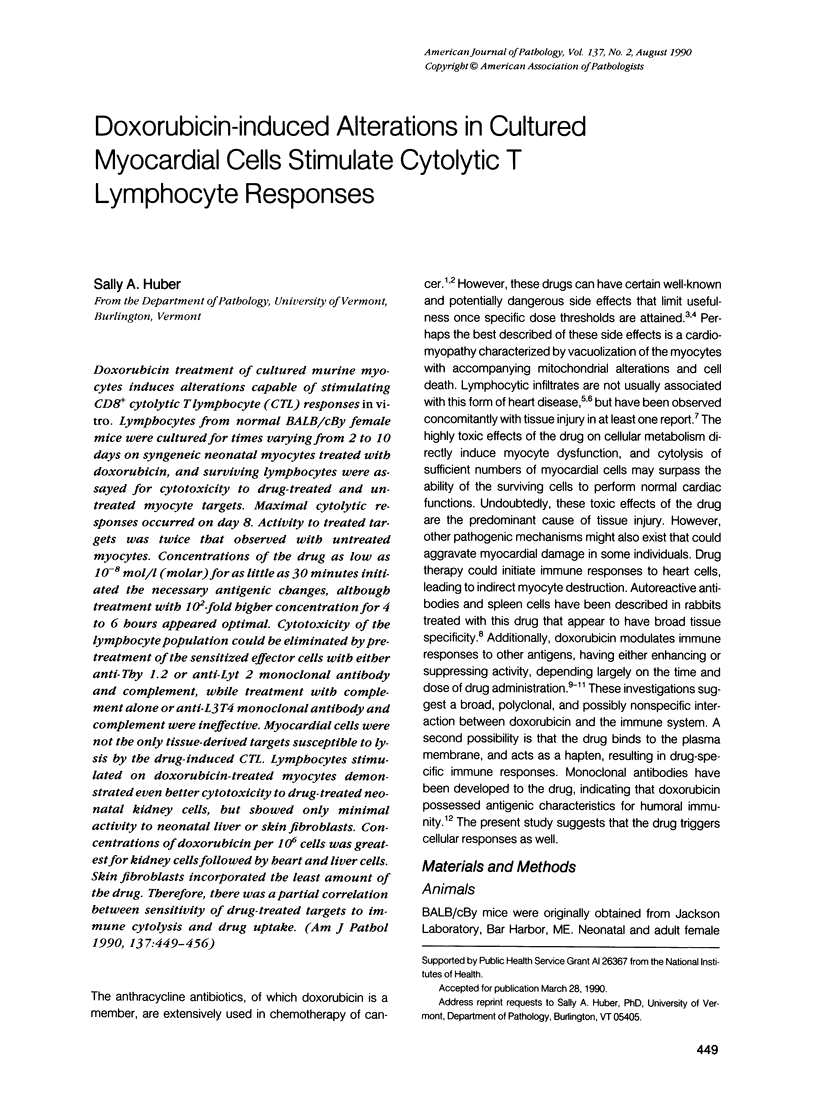

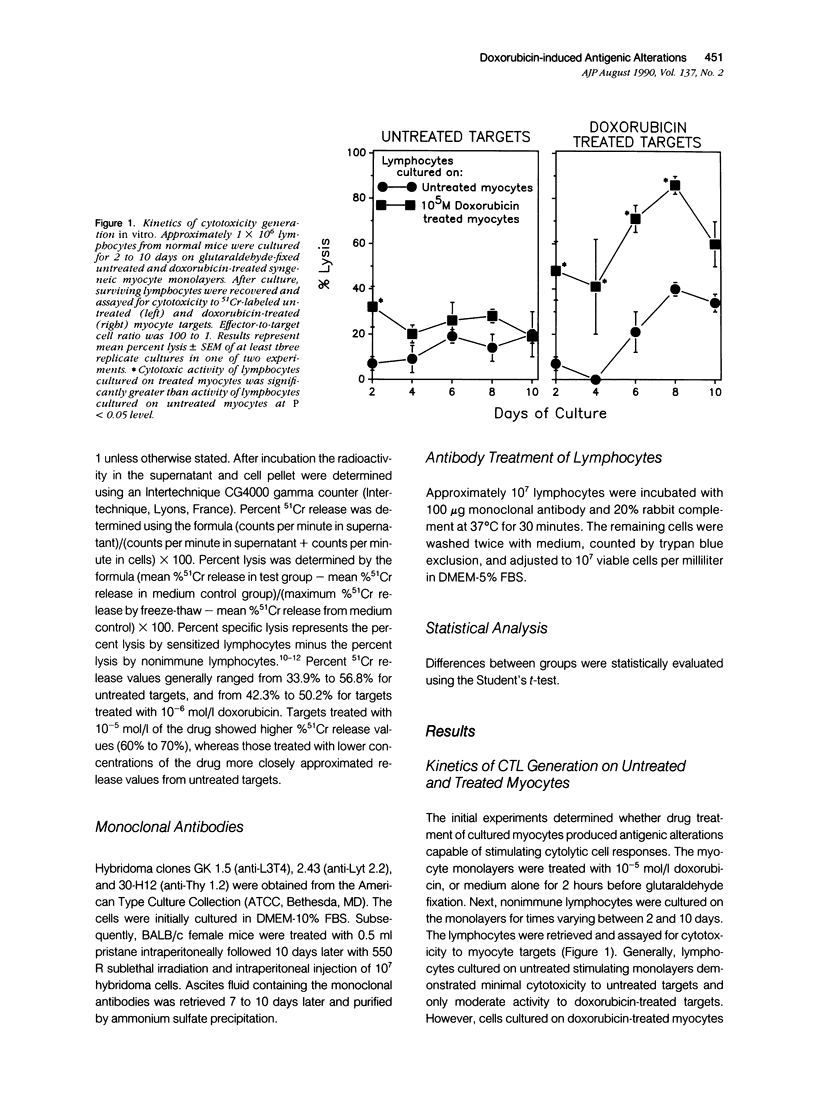

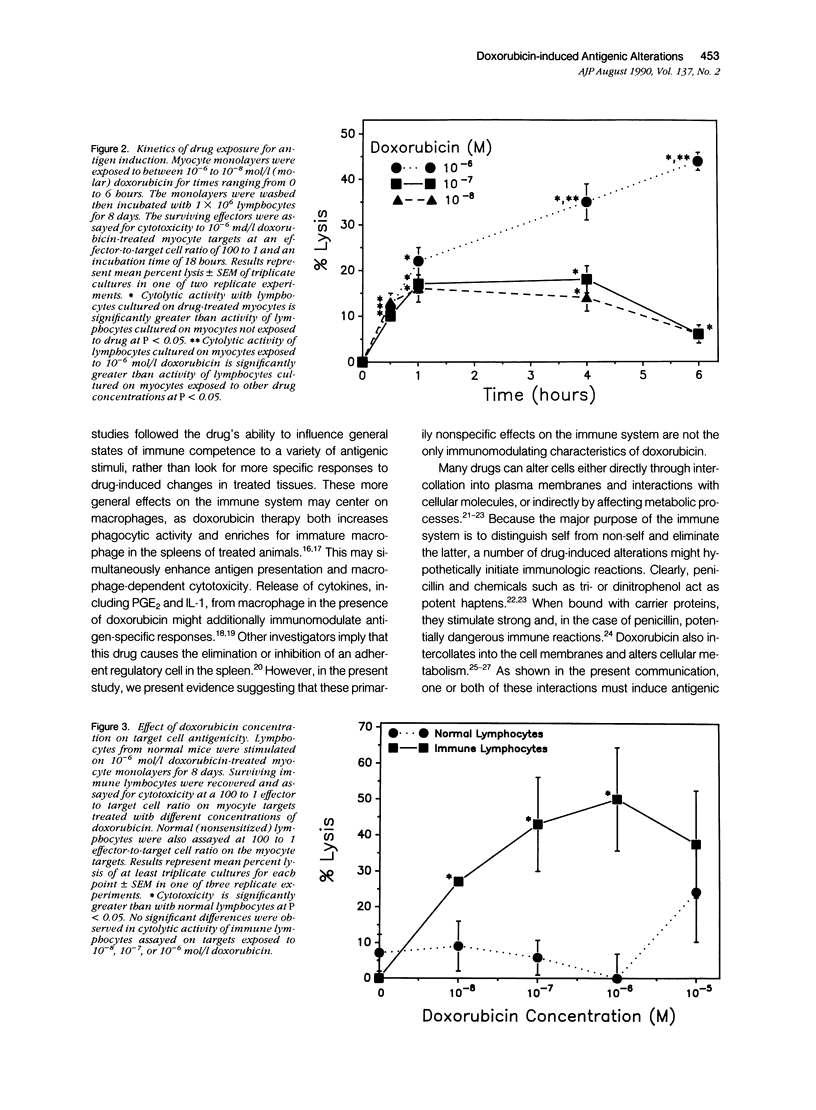

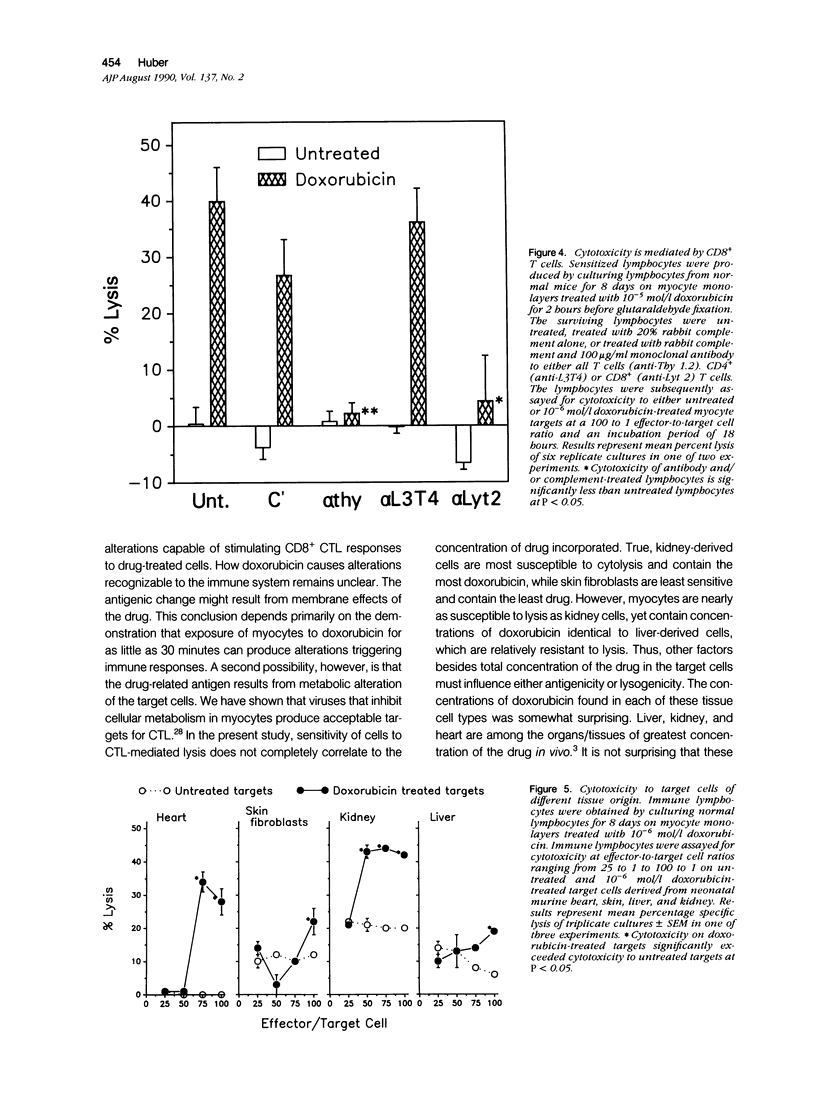

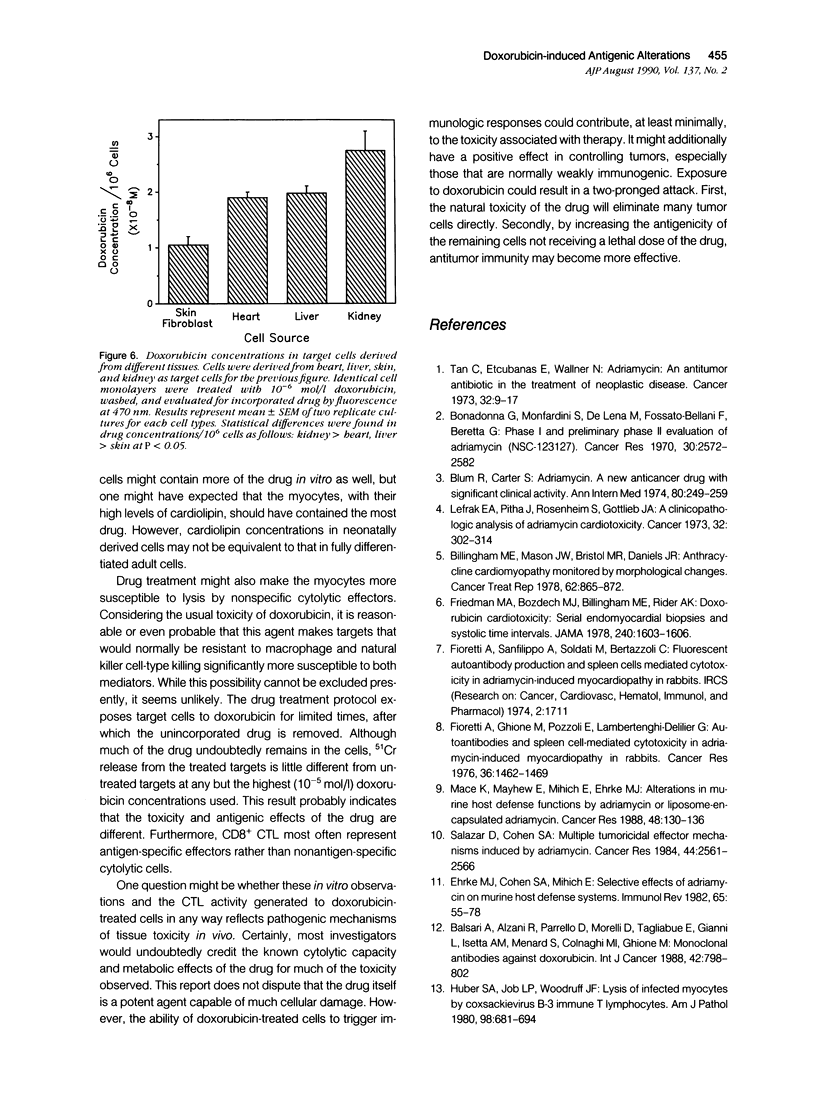

Doxorubicin treatment of cultured murine myocytes induces alterations capable of stimulating CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses in vitro. Lymphocytes from normal BALB/cBy female mice were cultured for times varying from 2 to 10 days on syngeneic neonatal myocytes treated with doxorubicin, and surviving lymphocytes was assayed for cytotoxicity to drug-treated and untreated myocyte targets. Maximal cytolytic responses occurred on day 8. Activity to treated targets was twice that observed with untreated myocytes. Concentrations of the drug as low as 10(-8) mol/l (molar) for as little as 30 minutes initiated the necessary antigenic changes, although treatment with 10(2)-fold higher concentration for 4 to 6 hours appeared optimal. Cytotoxicity of the lymphocyte population could be eliminated by pretreatment of the sensitized effector cells with either anti-Thy 1.2 or anti-Lyt 2 monoclonal antibody and complement, while treatment with complement alone or anti-L3T4 monoclonal antibody and complement were ineffective. Myocardial cells were not the only tissue-derived targets susceptible to lysis by the drug-induced CTL. Lymphocytes stimulated on doxorubicin-treated myocytes demonstrated even better cytotoxicity to drug-treated neonatal kidney cells, but showed only minimal activity to neonatal liver or skin fibroblasts. Concentrations of doxorubicin per 10(6) cells was greatest for kidney cells followed by heart and liver cells. Skin fibroblasts incorporated the least amount of the drug. Therefore, there was a partial correlation between sensitivity of drug-treated targets to immune cytolysis and drug uptake.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams D. O., Hamilton T. A. The cell biology of macrophage activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:283–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsari A., Alzani R., Parrello D., Morelli D., Tagliabue E., Gianni L., Isetta A. M., Menard S., Colnaghi M. I., Ghione M. Monoclonal antibodies against doxorubicin. Int J Cancer. 1988 Nov 15;42(5):798–802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingham M. E., Mason J. W., Bristow M. R., Daniels J. R. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy monitored by morphologic changes. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978 Jun;62(6):865–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum R. H., Carter S. K. Adriamycin. A new anticancer drug with significant clinical activity. Ann Intern Med. 1974 Feb;80(2):249–259. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna G., Monfardini S., De Lena M., Fossati-Bellani F., Beretta G. Phase I and preliminary phase II evaluation of adriamycin (NSC 123127). Cancer Res. 1970 Oct;30(10):2572–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S. K. Adriamycin-a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975 Dec;55(6):1265–1274. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelli M. G., Martini A., Colombo T., Bossi A., Garattini S. Heart levels of adriamycin in normal and tumor-bearing mice. Eur J Cancer. 1976 Nov;12(11):913–923. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(76)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrke M. J., Cohen S. A., Mihich E. Selective effects of Adriamycin on murine host defense systems. Immunol Rev. 1982;65:55–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1982.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrke M. J., Cohen S. A., Mihich E. Selectivity of inhibition by anticancer agents of mouse spleen immune effector functions involved in responses to sheep erythrocytes. Cancer Res. 1978 Mar;38(3):521–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrke M. J., Ryoyama K., Cohen S. A. Cellular basis for adriamycin-induced augmentation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity in culture. Cancer Res. 1984 Jun;44(6):2497–2504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioretti A., Ghione M., Pozzoli E., Lambertenghi-Deliliers G. Autoantibodies and spleen cell-mediated cytotoxicity in adriamycin-induced myocardiopathy in rabbits. Cancer Res. 1976 Apr;36(4):1462–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. A., Bozdech M. J., Billingham M. E., Rider A. K. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Serial endomyocardial biopsies and systolic time intervals. JAMA. 1978 Oct 6;240(15):1603–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.240.15.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa S., Ovary Z. Heteroclitic antibodies: differences in fine specificities between monoclonal antibodies directed against dinitrophenyl and trinitrophenyl haptens. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1988;85(2):238–243. doi: 10.1159/000234509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. A., Heintz N., Tracy R. Coxsackievirus B-3-induced myocarditis. Virus and actinomycin D treatment of myocytes induces novel antigens recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1988 Nov 1;141(9):3214–3219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. A., Job L. P., Woodruff J. F. In vitro culture of coxsackievirus group B, type 3 immune spleen cells on infected endothelial cells and biological activity of the cultured cells in vivo. Infect Immun. 1984 Feb;43(2):567–573. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.567-573.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S. A., Job L. P., Woodruff J. F. Lysis of infected myofibers by coxsackievirus B-3-immune T lymphocytes. Am J Pathol. 1980 Mar;98(3):681–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafaye P., Lapresle C. Fixation of penicilloyl groups to albumin and appearance of anti-penicilloyl antibodies in penicillin-treated patients. J Clin Invest. 1988 Jul;82(1):7–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI113603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrak E. A., Pitha J., Rosenheim S., Gottlieb J. A. A clinicopathologic analysis of adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Cancer. 1973 Aug;32(2):302–314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197308)32:2<302::aid-cncr2820320205>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace K., Mayhew E., Mihich E., Ehrke M. J. Alterations in murine host defense functions by adriamycin or liposome-encapsulated adriamycin. Cancer Res. 1988 Jan 1;48(1):130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini F., Pavelic Z., Mihich E. Increased primary cell-mediated immunity in culture subsequent to adriamycin or daunorubicin treatment of spleen donor mice. Cancer Res. 1977 Jun;37(6):1719–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar D., Cohen S. A. Multiple tumoricidal effector mechanisms induced by adriamycin. Cancer Res. 1984 Jun;44(6):2561–2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni A., Riccardi C., Sorci V., Herberman R. B. Effects of adriamycin on the activity of mouse natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1980 May;124(5):2329–2335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue M. A., Noritake D. T., Klaustermeyer W. B. Penicillin anaphylaxis: fatality in elderly patients without a history of penicillin allergy. Am J Emerg Med. 1988 Sep;6(5):456–458. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(88)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C., Etcubanas E., Wollner N., Rosen G., Gilladoga A., Showel J., Murphy M. L., Krakoff I. H. Adriamycin--an antitumor antibiotic in the treatment of neoplastic diseases. Cancer. 1973 Jul;32(1):9–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197307)32:1<9::aid-cncr2820320102>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. M. Drug-induced autoimmune disease. Fed Proc. 1974 Aug;33(8):1894–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triton T. R., Yee G. The anticancer agent adriamycin can be actively cytotoxic without entering cells. Science. 1982 Jul 16;217(4556):248–250. doi: 10.1126/science.7089561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]