Abstract

Recent research has highlighted the importance of auxin concentration gradients during plant development. Establishment of these gradients is believed to involve polar auxin transport through specialized carrier proteins. We have used an experimental system, the wood-forming tissue of hybrid aspen, which allows tissue-specific expression analysis of auxin carrier genes and quantification of endogenous concentrations of the hormone. As part of this study, we isolated the putative polar auxin transport genes, PttLAX1–PttLAX3 and PttPIN1–PttPIN3, belonging to the AUX1-like family of influx and PIN1-like efflux carriers, respectively. Analysis of PttLAX and PttPIN expression suggests that specific positions in a concentration gradient of the hormone are associated with different stages of vascular cambium development and expression of specific members of the auxin transport gene families. We were also able demonstrate positive feedback of auxin on polar auxin transport genes. Entry into dormancy at the end of a growing season leads to a loss of auxin transport capacity, paralleled by reduced expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes. Furthermore, data from field experiments show that production of the molecular components of the auxin transport machinery is governed by environmental controls. Our findings collectively demonstrate that trees have developed mechanisms to modulate auxin transport in the vascular meristem in response to developmental and environmental cues.

One of the biggest differences between animal and plant growth is the astounding plasticity of plant development, allowing plants to survive even severe perturbations caused by wounding, chemicals, or changes in the environment by adapting their growth behavior. This plastic growth behavior, however, requires a system that provides each developing cell with information about its relative position in the surrounding tissue, as well as the overall environment of the plant. One of the components that has the potential to act both as a morphogen conferring positional information, as well as a transmitter of environmental signals, is indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the most abundant auxin in plants.

Auxin appears to have important roles in a wide range of developmental processes including embryogenesis (1), gravitropism (2), lateral root formation (3), and the formation of vascular strands (4). An attractive model describing the way auxin may mediate its effects postulates the involvement of hormone gradients across tissues or organs, in a manner that could provide the developing cells with positional information or trigger differential growth responses. These gradients should be established rapidly in response to environmental cues, e.g., in cases of tropic growth, whereas in other cases they could be of a more stable nature, such as gradients associated with the development of the primary root (for a review, see refs. 5 and 6). To understand the roles of auxin gradients in plant development, we need to know how they are established and maintained. Unlike other plant hormones, the control of auxin concentrations is not limited to homeostatic mechanisms like biosynthesis, conjugation, and catabolism; it also involves active transport of auxin in a polar fashion (7). Polar auxin transport (PAT) is driven by the proton motive force across the plasma membrane and utilizes specialized membrane carriers for both entering and exiting the cell. The subcellular location of these transport proteins is thought to be responsible for controlling the direction of auxin flux (8–10). The putative auxin influx carrier AUX1 belongs to a family of four highly homologous proteins in Arabidopsis that are members of the auxin amino acid permease family of proton-driven transporters (reviewed in ref. 11). The efflux function appears to depend on the AtPIN/AGR/EIR family of proteins, of which there are eight members in Arabidopsis, all showing homology to bacterial transporters (reviewed in ref. 12).

Research on the function of these transport proteins has already provided some insight into how PAT can control auxin gradients in pattern formation (13) and environmental responses (2). However, studies on how such hormone concentration gradients control development in Arabidopsis are still hampered by the difficulties involved in simultaneously measuring hormone concentration and gene expression accurately at the cellular level. Another complication is that the cellular concentration of auxin in all tissues so far studied is a result of the combined effects of transport and homeostatic mechanisms. However, almost all of these problems can be circumvented in the wood-forming tissues of trees. This is because the highly ordered differentiation of specific cell types leading to mature wood allows the sampling of tissues at different developmental stages, and the measurement of hormone levels and gene expression at almost cellular resolution (14, 15). This tissue is also unique from a biochemical perspective because it is one of very few tissues where the transport machinery is believed to be the main regulatory factor because the types of cells present in it have a very low capacity to synthesize, catabolize, and conjugate auxin (ref. 16 and A. Östin and G.S., unpublished data).

Wood is formed through the cyclic activity of the vascular cambium, adding phloem and xylem cells to the outer and inner part of the stem, respectively. The overlap of an auxin concentration gradient and a developmental gradient across the wood-forming tissue has led to the suggestion that auxin could act as a positional signal in wood formation (15). There is further evidence for an involvement of auxin in the response of the cambium to various environmental signals. One of these signals is perceived at the end of the growing season, when the vascular cambium suspends growth and enters dormancy. This change in activity is paralleled by a change in sensitivity to the growth-promoting effects of apically applied auxin (17) as well as a loss of auxin transport capacity (18, 19).

In this report, we have used an experimental system that allows the separation of auxin homeostasis from transport mechanisms, as well as the simultaneous monitoring of auxin levels and gene expression with tissue-specific resolution. We show that two families of hybrid aspen polar auxin transport genes are differentially expressed in relation to the endogenous auxin gradient as well as specific cell types during wood development. We have also analyzed the dynamic nature of the transport machinery and demonstrated that members of the auxin transport genes are under both developmental and environmental control.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of PttLAX and PttPIN Genes. PttLAX1 and PttPIN1–PttPIN3 were identified as expressed sequence tags in populusdb (http://poppel.fysbot.umu.se). Fragments for PttLAX2 and PttLAX3 were obtained by RT-PCR using the degenerate primers pan (ATTTTTTGGGG) and 3che (GGGGAAAATTTT) for conserved regions in the AUX1-like genes. Because all clones thus obtained contained truncated coding sequences, full-length clones were obtained either by screening a cDNA library prepared from cambial scrapings of hybrid aspen (PttLAX1 and PttLAX3) or by 5′ and 3′ RACE using the Marathon system (CLONTECH).

Expression Analysis in Stem Tissues and Apical–Basal Gradient. For the experiment in Fig. 1, high resolution expression patterns in the stem were measured as described in (20). For the apical–basal gradient in Fig. 2 the upper regions of greenhouse-grown hybrid aspen shoots were divided into internodes 1–6, 7–10, 10–16, and 17–20. Leaves and internodes from five shoots were pooled and used for RNA extractions. Expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was measured by using Northern hybridization on 20 μg of total RNA. Selected internodes were hand-sectioned, stained with toluidine blue in 20% CaCl followed by ruthenium red, and mounted in 50% glycerol. With this stain, secondary walls appear blue and primary walls appear red.

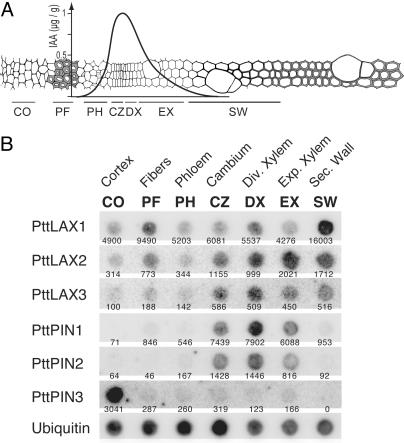

Fig. 1.

Expression of hybrid aspen PAT genes in stem tissues. (A) Schematic cross section through a hybrid aspen stem. The graph shows the approximate distribution of IAA (μg/g fresh weight) in the different tissues based on data from ref. 23. Horizontal bars indicate the location of tissue samples from different developmental zones. CO, cortex; PF, phloem fibers; PH, phloem; CZ, cambium; DX, dividing xylem mother cells; EX, expanding xylem; SW, zone of secondary wall formation. (B) Expression of PAT genes in the different developmental zones of the cambial region. Numbers below spots indicate spot intensities, normalized to the ubiquitin control.

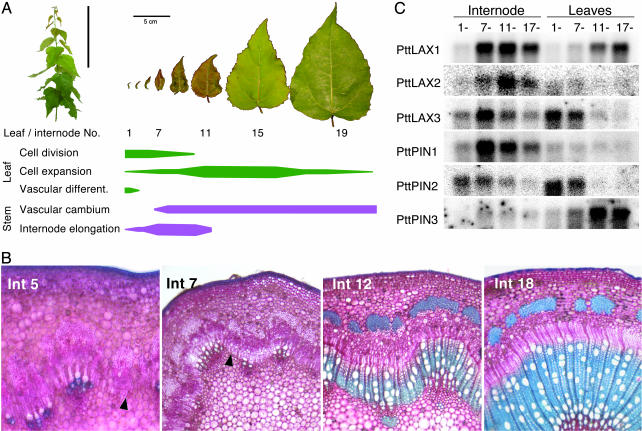

Fig. 2.

Expression of hybrid aspen PAT genes during shoot development. The apical region of a growing aspen shoot was subdivided into four regions (internodes 1–6, 7–10, 11–16, and 17–20) and the expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes analyzed in internodes and leaves of each region. (A)(Upper Left) Typical shoot used for the experiment. Leaf specimens show the increase in size along the shoot axis; important developmental events in leaf and stem development are indicated by horizontal bars. (B) Microsections through internodes 5, 7, 12, and 18 along the apical region showing the establishment and expansion of the wood-forming tissues. Arrows in internodes 5 and 7 indicate the absence and recent initiation of a continuous vascular cambium. (C) Northern blot with expression profile of PttLAX and PttPIN genes in the different developmental regions.

Auxin Induction. Approximately 6-cm-long and 2- to 3-mm-thick stem pieces of in vitro grown Populus tremula × tremuloides were cut, defoliated, and immediately immersed in 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium. Samples were taken after 0, 2, 4, 8, and 16 h. After 16 h of incubation, 20 μM of IAA was added to the MS medium, and the stems were further incubated for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h before harvesting. IAA content was determined as described in ref. 21. PttLAX and PttPIN gene expression was determined by relative RT-PCR with help of the Quantum 18S RNA internal standard kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Seasonal Expression and Auxin Transport. The in vitro dormancy induction was carried out on ≈120-cm-tall Populus plants grown in a climate chamber under the following conditions: 18-h day at 20°C and 6-h night at 15°C. Dormancy was induced by shortening the day length to 8 h. One-year-old shoots were sampled from wild-grown P. tremula between spring and autumn of 2001.

For auxin transport measurements, 5-mm internode segments were stood upright on receiver agar blocks, and a donor block containing 35 μM 14C IAA (57 mCi/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) was placed on top of the segments. After an 8-h incubation at room temperature in a moist chamber, translocated IAA was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. RNA from whole internodes was used for RT-PCR as described in Auxin Induction.

Results

Cloning of Poplar Auxin Transport Genes. We began our efforts to understand the role of PAT in wood formation by cloning homologues of AtLAX and AtPIN genes from hybrid aspen, P. tremula × tremuloides. There is considerable indirect evidence indicating that AtLAX and AtPIN proteins are either membrane carriers themselves or closely associated with such carriers (reviewed in refs. 11 and 12). We therefore refer to AtLAX, AtPIN, and their hybrid aspen homologues as PAT genes. The hybrid aspen PAT genes were identified either as expressed sequence tags in populusdb or through PCR using degenerate primers. A total of three AtAUX1 and three AtPIN1 homologues were identified and named PttLAX1–PttLAX3 (like AUX1) and PttPIN1–PttPIN3, respectively. Overall homology among the LAX proteins is very high, with values between 72% and 84% amino acid identity between all of the aspen and Arabidopsis proteins; even when compared with the monocot homologues like ZmLAX from maize, identities are between 67% and 71% (ref. 22 and Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). In the LAX proteins homology is high along the entire sequence with exception of the amino and carboxyl termini. The converse is true for the PIN proteins, which are characterized by highly conserved N- and C-terminal domains with large stretches of variation in the central region (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

PttLAX and PttPIN Genes Show Differential Expression in the Wood-Forming Zone. Auxin is distributed in a steep concentration gradient across the cambial region (15), implying the existence of mechanisms that are able to establish the gradient and control its shape. PAT presents a likely candidate for this mechanism because this tissue has only limited capacity to use homeostatic mechanisms to control the cellular pool size of the hormone (16). To test whether PttLAX or PttPIN genes could be involved in this process, their expression was analyzed in a series of tangential microsections across the wood-forming tissues (Fig. 1). Expression profiles of PttLAX3, PttPIN1, and PttPIN2 were most similar, showing expression in the cambium and adjacent dividing xylem mother cells. In the case of PttLAX2, the expression extended into the zones of cell expansion and secondary wall formation. Very different results were obtained for PttLAX1, with a maximal expression in phloem fibers and secondary-wall-forming xylem. These cells are at the flanks of the auxin gradient, and both undergo secondary wall formation. The most specific pattern was found for PttPIN3, which was only expressed in the cortex layer of the stem.

Expression in an Apical–Basal Gradient. The data in Fig. 1 describe the expression patterns of PttPIN and PttLAX in mature wood, where major developmental steps like differentiation of vascular strands and the establishment of the interfascicular cambium have already taken place. To identify possible functions for aspen PAT genes in these early developmental events, we analyzed their expression in an apical–basal developmental gradient by sampling internodes and leaves of increasing size. For this procedure, the apical region was subdivided into four zones based on the growth rate of internodes and leaves (Fig. 2 A) and gene expression was analyzed separately in leaves and internodes by using Northern hybridization. In the stem, most of the primary vascular development takes place in internodes 1–6. Most PAT genes showed very low expression in this region except for PttPIN2, which had the strongest signals in internodes 1–10. PttLAX1, PttLAX3, and PttPIN1 were mainly expressed in internodes 7–11. The anatomy of the stem shows the establishment of the vascular cambium around internode 7, indicating that the strongest expression of PttLAX1, PttLAX3, and PttPIN1 coincides with the initiation of a functional meristem. The signal for PttLAX2 was found to peak in internodes 11–16, a region characterized by the onset of large-scale secondary wall formation in the xylem. This finding correlates well with the expression of PttLAX2 on the xylem side of wood-forming tissues, as shown in Fig. 1. Expression patterns in leaves fall into three classes. PttLAX2 and PttPIN1 show only very weak signals in any leaf tissue. Both PttLAX3 and PttPIN2 were expressed mostly in the youngest leaves, where processes like cell division and the establishment of vascular strands take place. In contrast, PttLAX1 and PttPIN3 expression was highest during later stages of leaf development and in fully mature leaves.

PttLAX and PttPIN Genes Are Auxin Inducible. The possibility of a feedback regulation of PAT genes by auxin was tested in an auxin-treatment experiment. Initial studies in which stem pieces were incubated in auxin-containing media revealed no apparent difference in PAT gene expression between control and treated tissues (data not shown). This may have been caused by steady-state IAA levels in stems, which are sufficient for maximal expression of the PAT genes even without exogenous additions. To test this hypothesis, stem pieces of tissue culture-grown hybrid aspen were incubated in growth medium to deplete them of endogenous IAA. After 16 h of depletion, the IAA concentration had decreased from 57 ± 6 pg of IAA per mg fresh weight to 13 ± 2 pg/mg. IAA was then added to a concentration of 20 μM. We were not able to reliably quantify endogenous IAA after application because of contamination from incubation media, but we are confident that the induction of expression described below is caused by IAA because two members of the well characterized auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene family PttIAA1 and PttIAA5 (20) are induced in a similar fashion to the PAT genes (data not shown) and auxin-responsiveness of aspen PAT genes was also observed in experiments in which IAA was applied through the polar transport stream (data not shown).

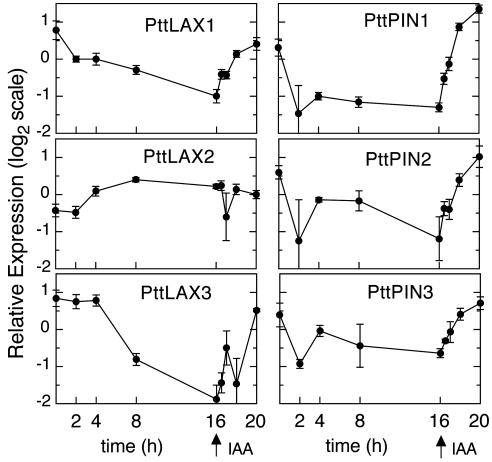

Expression analysis revealed a continuous decline of PAT gene expression during the depletion phase (Fig. 3). The addition of IAA then led to a rapid induction of expression, with measurable differences after only 30 min. The expression of the PttLAX1 and PttLAX3 influx carriers returned to control levels after 4 h of IAA treatment. For the efflux genes, however, induction was stronger, reaching up to double control levels. The dynamics of down-regulation during the depletion phase showed clear differences between the six analyzed genes. PttLAX1 and the PttPIN genes responded with a rapid initial drop after 2 h of depletion. PttLAX3 expression on the other hand remained constant for at least 4 h before dropping. Interestingly, the behavior of PttLAX2 was completely different from that of the remaining genes. Auxin depletion led to a slight up-regulation of PttLAX2 expression, which was not significantly affected by auxin addition.

Fig. 3.

Auxin responsiveness of the aspen PAT genes. Defoliated stem segments of hybrid aspen were incubated in growth medium to deplete them of endogenous auxin. After 16 h, IAA was added to 20 μM and incubation was continued for 4 h. Samples were taken at the indicated time points, and the expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was analyzed by using RT-PCR. Data shown are the average of at least three replicates, and error bars indicate SD.

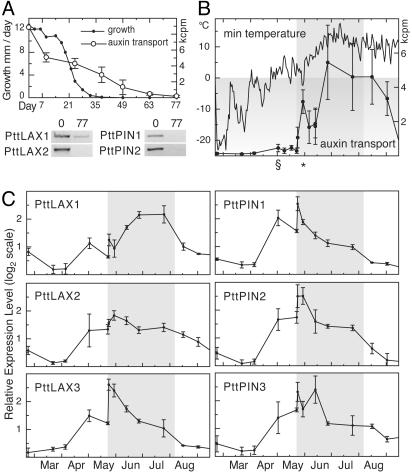

Seasonal Control of Auxin Transport. At the end of a growing season, the vascular cambium is deactivated in response to a short-day signal (24), leading to loss of cambial growth together with reductions in auxin transport capacity and auxin sensitivity (17, 19). To analyze whether this environmentally triggered response is caused by alterations in the expression of aspen PAT genes, trees were triggered to enter dormancy by subjecting them to short days in a climate chamber. The expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was determined at the start and end points of the treatment, i.e., active growth and dormancy (Fig. 4A). PttLAX3, PttPIN1, and PttPIN4 transcripts were reduced below detection limit (<10% of the active value) when the tissue reached the dormant stage, wereas PttLAX1 remained at 40% of the active value. Measurements of growth rate and transport capacity during the entire active–dormancy transition revealed that the transport capacity dropped rapidly after the short-day signal, well in advance of the reduction in growth rate (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

(A) Aspen trees were subjected to short-day treatment in a climate chamber. Growth increment and auxin transport capacity were measured at weekly intervals. Expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was measured at the beginning and end of treatment. (B) One-year-old shoots were sampled from wild growing P. tremula. The upper graph illustrates the minimum daily temperature during the experiment; the § indicates the point from where on minimum temperatures are above freezing point for a prolonged time. The asterisk indicates two nights with frost that occurred after bud break. The shaded area marks the time between bud break and bud set. Values for polar auxin transport are amount of 14C IAA translocated in 8 h, expressed as 103 cpm (kcpm). The graph shows the average of eight stem segments, with error bars indicating SD. (C) Expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was measured by using RT-PCR. Data shown are the average of at least three replicates, and error bars indicate SD. Shading and time points are the same as in B.

The results from the dormancy transition experiment described above encouraged us to undertake a field experiment, in which expression levels of the auxin transporters and auxin transport capacity were measured in young twigs of wild-grown P. tremula throughout a seasonal cycle. During the winter, auxin transport capacity was minimal (Fig. 4B). Any observed translocation of labeled IAA was of the same magnitude in both upward and downward orientation [113 ± 37 cycles per min (cpm) downward and 136 ± 80 cpm upward on March 22, 2001], indicating that the movement is mainly nonpolar. During this time, expression of PttLAX and PttPIN genes was minimal (Fig. 4C). The first change was observed when minimum temperatures stayed above zero degrees for a period of several days at the end of April, with significant (P < 0.05) up-regulation of the expression of all transporters analyzed. Auxin transport capacity was increased only marginally at this point, but more importantly, there was a significant difference between upward and downward transport (456 ± 216 cpm downward, 147 ± 48 cpm upward, P = 0.003) that correlated well with the appearance of the molecular components of the transport machinery. At this stage, however, there were still no visible changes in stem anatomy or bud morphology. The next stage was marked by the breaking of buds on May 23, providing major sites of auxin biosynthesis in form of expanding leaves. On bud break, the auxin transport capacity increased >10-fold within a single day, paralleled by a leap in the expression of all PAT genes, with the exception of PttLAX2. The following two sampling points in early June showed a drop in transport capacity. This drop coincides with the occurrence of two nights with temperatures below the freezing point, which seem to have affected the transport capacity, albeit without changing the expression of the PAT components. Transport capacity reached a maximum in mid-June and stayed at constantly high levels until after bud set. The decline of transport capacity in late August was paralleled by a cessation of cambial activity (data not shown). With the exception of PttLAX1, all aspen PAT genes showed a constant decline in expression from a maximum at bud break.

Discussion

Functional Specificity Versus Sequence Similarity. The LAX and PIN sequences form small gene families in Arabidopsis, Populus, and other species (11, 12, 22, 25, 26). The high degree of homology with each other and other classes of membrane permeases, as well as the observed phenotypes in knockout mutants suggest that they could all perform, or be closely associated with, the same basic biochemical function of translocating auxin across the plasma membrane. Given this assumption, what is the reason for the existence of several independent genes? One possible explanation is that different members of the respective families have the ability to interact specifically with various components of the cellular machinery, which would allow the existence of overlapping transport streams formed by proteins produced in the same cell but directed to different locations along the cell periphery in response to specific signals. This could be the case for PttLAX2 and PttLAX3 as well as for PttPIN1 and PttPIN2, which show partially overlapping expression patterns in the wood-forming tissues (Fig. 1) but have different expression characteristics in the different zones of the developing shoot (Fig. 2). The data available from Arabidopsis, where mutations in individual PIN genes lead to very distinct phenotypes, strongly support such functional specificity (2, 10, 13, 27).

PttLAX1 Could Be Involved in Xylem Maturation. The data presented here are in accordance with several findings connecting auxin, PAT, and xylem maturation. (i) The expression of PttLAX1 is mainly associated with mature tissues such as older internodes and leaves (Fig. 2C) as well as cells undergoing secondary wall formation and programmed cell death (Fig. 1). (ii) An AUX1 homologue in Zinnia is expressed during the transdifferentiation from mesophyll to xylem cells, and its transcript has been localized to immature xylem (28). (iii) PAT inhibitors block tracheary element formation in cultured Zinnia cells (29). (iv) PttIAA5, a member of the early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA family in aspen shows an expression pattern very similar to that of PttLAX1 (20). One possible role for PAT in xylem maturation could be to provide positional cues for the formation of perforations in the cell walls (30). A role in triggering cell death is also conceivable based on findings in norway spruce, where removal of auxin and cytokinin from the growth medium is a prerequisite for the progression of cell death (31). In the latter case, expression of PttLAX1 could be localized to parenchyma cells in both xylem (ray cells) and phloem cells that take up auxin from their secondary wall-forming neighbors, thus allowing them to proceed into programmed cell death.

The Creation of Auxin Gradients. In the vascular cambium, there are at least two conceivable routes for PAT. The major stream is believed to go along the longitudinal axis of the stem through the cambium and its youngest derivatives (19). The expression patterns of PttLAX3, PttPIN1, and PttPIN2 are compatible with an involvement in this transport route. A second possible transport route is in the radial direction. Here PAT could be responsible for establishing and maintaining the concentration gradient of IAA, which has been observed in the cambial region (15, 23). The auxin gradient in turn would provide a morphogenetic guideline for the differentiation of cambial derivatives. A similar role for PAT has been demonstrated in Arabidopsis root development where mutations in AtPIN4 abolish the formation of an auxin gradient and lead to abnormal patterns of cell division (13). The role of PAT genes in the stem could be one of counteracting diffusional leakage of IAA from the longitudinal transport stream in the cambial zone. Alternatively, there might be a small amount of active radial transport of the hormone away from the cambial zone.

During establishment of the interfascicular cambium, according to the signal flow canalization hypothesis (32), there should be tangential/lateral transport of IAA from the existing primary vascular bundles into the adjacent parenchyma. This flow, it is postulated, should eventually lead to the dedifferentiation of parenchyma into cambial cells. The required auxin transport could be mediated by PttPIN2 because its expression in the cambial zone (Fig. 1) in very young internodes and young leaves coincides in space and time with the process of vascular differentiation. The persistence of PttPIN2 expression in the cambium, even after establishment of a continuous ring of meristem, could be an adaptive mechanism ensuring the maintenance of a continuous vascular cambium through a constant lateral distribution of auxin, thus preventing any cell from dedifferentiating into parenchyma.

Auxin Inducibility and the Signal Flow Canalization Hypothesis. A central requirement for the signal flow canalization hypothesis is positive feedback regulation of auxin transport (32). A cell that takes up and transports auxin should increase its capacity to transport the hormone. There are, however, no data on the molecular mechanisms of such a positive feedback. There is considerable evidence for the regulation of PAT through phosphorylation and via factors interacting with the NPA-binding protein (for a review, see ref. 33). There are further data on how the activity of PAT is regulated through changes in the vesicular trafficking required for transporting PAT proteins to the plasma membrane (34). Our observation that IAA rapidly induced aspen PAT genes provides the first indication that a positive feed-back of auxin on auxin transport might be achieved at the transcriptional level.

However, such positive feedback does not seem to be common to all PAT genes, as indicated by the contrasting behavior of PttLAX2. Nor is the influence of auxin restricted to the mRNA level, because it was shown by Sieberer et al. (35) that the EIR1 (AtPIN2) protein is destabilized by auxin application, whereas mRNA levels are not affected.

These distinct modes of regulation most likely reflect the different roles of individual PAT genes in plant development. AtPIN2 is involved in root gravitropism, where the plant shows a transient change in root elongation in response to changes in the gravity vector. It has been suggested that feedback of auxin on AtPIN2 protein could be a rapid mechanism to return the root to steady state once elevated auxin has induced the bending process (35). The process of vascular differentiation, however, requires a subset of cells to acquire a constantly increased capacity for auxin transport in response to increased hormone levels. The auxin responsiveness of PttPIN1–PttPIN3, PttLAX1, and PttLAX3 transcription is compatible with this model. The results further suggest that, in tissues with high growth rates and a stable pattern of growing cells, expression of PAT genes is at a maximum, probably because auxin transport has already been restricted to specific, appropriate cells in such tissues.

Studies involving application of PAT inhibitors have suggested that the differentiation of leaf vasculature depends on a functional PAT system in early stages of leaf development (4). The expression of PttPIN2 specifically in young developing leaves, together with its inducibility by auxin, suggests that this protein could be involved in early stages of vascular differentiation.

Changes in PAT During Dormancy Affect Auxin Responsiveness. In an adaptive response that allows them to survive the harsh conditions during winter, trees enter dormancy at the end of the growing season. Leaves are shed, and both apical and cambial growth is suspended. It has been shown in studies involving the application of IAA in lanolin to decapitated stems that entry into dormancy makes the cambium insensitive to the normal growthpromoting effects of auxin (17). The apparent loss of sensitivity can be explained by the findings of Lachaud and Bonnemain (19) showing that the capacity for PAT is strongly reduced during the dormant period. Apically applied auxin might simply not penetrate into the underlying tissues. This loss of auxin transport capacity was confirmed by our measurements in twigs of field-grown P. tremula, whereas the analysis of aspen PAT gene expression shows that the corresponding mRNA levels fall to a minimum during the winter dormancy.

In spring, the auxin transport system needs to be reactivated. The first observable event is an increase in the expression of the PAT genes, during which the overall auxin transport capacity remains unchanged. This induction of transcription is most likely triggered by the first continuous stretch of days with a minimum temperature above zero degrees. Although the increased transcription of PAT genes does not cause a major increase in transport capacity, it is a likely cause of the appearance of polarity in the transport process. During winter, any translocation that can be measured is most likely due to diffusion because it is independent of the orientation of the stem, and not affected by temperature or PAT inhibitors (data not shown). Induction of PAT gene expression before bud break could be a mechanism to provide enough transport proteins to ensure polarity of auxin movement once the major auxin sources are activated.

The next stage in spring reactivation is marked by a strong increase of transport capacity at bud break, possibly via a positive feed back mechanism. Young and expanding leaves have been identified as major sites of auxin synthesis (36). Newly synthesized auxin from the expanding leaves could thus provide a signal for the posttranscriptional activation of PAT proteins. It is clear, however, that a growing apex is not required for maintenance of PAT capacity because the transport capacity is preserved until well after bud set in the autumn.

The newly synthesized auxin may also be responsible for the observed jump in mRNA levels of several aspen PAT genes at bud break. Another interesting finding is that the transport capacity remains close to maximum levels even in mid-August, when anatomical studies indicate that cambial activity ceases. We can therefore conclude that neither an actively growing cambium nor expanding leaves are necessary for maintaining a high auxin transport capacity.

It appears that environmental factors can have a profound effect on auxin transport. This is exemplified by the dip in transport capacity after two nights of frost in early June. Because mRNA levels were not affected, damage caused by the frost must affect either the translation or proper localization of PAT protein.

Judging from the expression patterns shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the best candidates for proteins involved in the observed downward auxin transport are PttLAX3 and PttPIN1, because they are active in the cambial region and also detected in the mature parts of the stem. Both genes show very similar behavior during the seasonal cycle, with a peak in expression just after bud break followed by a steady decline until the end of the growing season. The lack of correlation between the expression of PttLAX3 and PttPIN1 on one hand, and the observed transport capacities on the other, can be explained in several ways. When considering the results shown in Fig. 2, it is important to note that the expression studies were performed on entire twig segments. An apparent change in gene expression may therefore result from either a change in the number of mRNA copies per cell, or a change in the relative number of cells expressing the gene, or a combination of both of these factors. In this respect, it may be informative to consider the expression patterns observed in Fig. 2. Expression of PttLAX3 and PttPIN1 genes, for instance, is restricted to a subset of cells that increase in number when the cambium is activated (meristematic and xylem mother cells), but whose relative contribution to the cell population of a growing twig decreases as the year progresses.

We have used the wood-forming tissues of hybrid aspen as a model system, which allows the separation of the transport machinery from homeostatic mechanisms involved in regulating the pool size of auxin. The diverse expression patterns and modes of regulation of PttLAX and PttPIN genes in the wood-forming tissues suggest a complex interaction of diverse transport streams, regulated by both developmental and environmental signals. A challenge for future research in this field will be to dissect these potentially overlapping transport streams and to identify the exact roles of individual components of the auxin transport machinery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Swedish Research Council and the European Union Popwood Project.

Abbreviations: IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; PAT, polar auxin transport.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos.: PttPIN1, AF190881; PttPIN2, AF515435; PttPIN3, AF515434; PttLAX1, AF115543; PttLAX2, AF190880; and PttLAX3, AF263100).

References

- 1.Liu, C. M., Xu, Z. H. & Chua, N. H. (1993) Plant Cell 5, 621–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friml, J., Wisniewska, J., Benkova, E., Mendgen, K. & Palme, K. (2002) Nature 415, 806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casimiro, I., Marchant, A., Bhalerao, R. P., Beeckman, T., Dhooge, S., Swarup, R., Graham, N., Inze, D., Sandberg, G., Casero, P. J. & Bennett, M. (2001) Plant Cell 13, 843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattsson, J., Sung, Z. R. & Berleth, T. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 2979–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muday, G. K. (2001) J. Plant Growth Regul. 20, 226–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamann, T. (2001) J. Plant Growth Regul. 20, 292–299. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomax, T. L., Muday, G. K. & Rubery, P. H. (1995) in Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Molecular Biology, ed. Davies, P. J. (Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands), pp. 509–530.

- 8.Müller, A., Guan, C. H., Galweiler, L., Tanzler, P., Huijser, P., Marchant, A., Parry, G., Bennett, M., Wisman, E. & Palme, K. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 6903–6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubery, P. H. & Sheldrake, A. R. (1974) Planta 188, 101–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gälweiler, L., Guan, C. H., Müller, A., Wisman, E., Mendgen, K., Yephremov, A. & Palme, K. (1998) Science 282, 2226–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry, G., Marchant, A., May, S., Swarup, R., Swarup, K., James, N., Graham, N., Allen, T., Martucci, T., Yemm, A., et al. (2001) J. Plant Growth Regul. 20, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palme, K. & Galweiler, L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friml, J., Benkova, E., Blilou, I., Wisniewska, J., Hamann, T., Ljung, K., Woody, S., Sandberg, G., Scheres, B., Jurgens, G. & Palme, K. (2002) Cell 108, 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hertzberg, M., Aspeborg, H., Schrader, J., Andersson, A., Erlandsson, R., Blomqvist, K., Bhalerao, R., Uhlen, M., Teeri, T. T., Lundeberg, J., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14732–14737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uggla, C., Mellerowicz, E. J. & Sundberg, B. (1998) Plant Physiol. 117, 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundberg, B. (1987) Ph.D. thesis (Swedish Univ. of Agricultural Sciences, Umeå, Sweden).

- 17.Little, C. H. A. & Bonga, J. M. (1974) Can. J. Bot. 52, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odani, K. (1975) J. Jpn. Forestry Soc. 57, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachaud, S. & Bonnemain, J. L. (1984) Planta 161, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyle, R., Schrader, J., Stenberg, A., Olsson, O., Saxena, S., Sandberg, G. & Bhalerao, R. P. (2002) Plant J. 31, 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edlund, A., Eklöf, S., Sundberg, B., Moritz, T. & Sandberg, G. (1995) Plant Physiol. 108, 1043–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochholdinger, F., Wulff, D., Reuter, K., Park, W. J. & Feix, G. (2000) J. Plant Physiol. 157, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuominen, H., Puech, L., Fink, S. & Sundberg, B. (1997) Plant Physiol. 115, 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe, G. T., Hackett, W. P., Furnier, G. R. & Klevorn, R. E. (1995) Physiol. Plant. 93, 695–708. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Billy, F., Grosjean, C., May, S., Bennett, M. & Cullimore, J. V. (2001) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ni, W. M., Chen, X. Y., Xu, Z. H. & Xue, H. W. (2002) Cell Res. 12, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luschnig, C., Gaxiola, R. A., Grisafi, P. & Fink, G. R. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2175–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demura, T., Tashiro, G., Horiguchi, G., Kishimoto, N., Kubo, M., Matsuoka, N., Minami, A., Nagata-Hiwatashi, M., Nakamura, K., Okamura, Y., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15794–15799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess, J. & Linstead, P. (1984) Planta 160, 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakashima, J., Takabe, K., Fujita, M. & Fukuda, H. (2000) Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 1267–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bozhkov, P. V., Filonova, L. H. & von Arnold, S. (2002) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 77, 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sachs, T. (1991) in Pattern Formation in Plant Tissues (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.), pp. 83–93.

- 33.Muday, G. K. & DeLong, A. (2001) Trends Plant Sci. 6, 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geldner, N., Friml, J., Stierhof, Y. D., Jurgens, G. & Palme, K. (2001) Nature 413, 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieberer, T., Seifert, G. J., Hauser, M. T., Grisafi, P., Fink, G. R. & Luschnig, C. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1595–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ljung, K., Bhalerao, R. & Sandberg, G. (2001) Plant J. 28, 465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.