Abstract

Demand for cosmetic genitoplasty is increasing. Lih Mei Liao and Sarah M Creighton argue that surgery carries risks and that alternative solutions to women's concerns about the appearance of their genitals should be developed

Women's concerns about their appearance, fuelled by commercial pressure for surgical fixes, now include the genitalia. A share of this consumer demand is being absorbed by National Health Service specialists. This article was prompted by the increased numbers of women asking for labial reduction and the concerns of clinicians about the rising number of referrals for cosmetic genital surgery.

A new complaint

More and more women are said to be troubled by the shape, size, or proportions of their vulvas, so that elective genitoplasty is apparently a “booming business.”1 Advertisements for cosmetic genitoplasty are common, often including before and after images and life changing narratives.2 Google produced around 490 000 results when we entered “labial reduction”. Forty seven of the first 50 results were advertisements from clinics in the United Kingdom and United States offering cosmetic genital surgery. Television programmes and articles in women's magazines on “designer vaginas” may also fuel desire for surgery, especially with the rising popularity of cosmetic surgery in general. The latest survey by the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons reported a staggering 31% increase in uptake of cosmetic surgery in the UK3; women accounted for 92% of this uptake.

Decisions about surgically altering the genitalia may be based on misguided assumptions about normal dimensions. Recently, we reported dimensions of female genitals based on 50 premenopausal women.4 Labial and clitoral size and shape, vaginal length, urethral position, colour, rugosity, and symmetry varied greatly. These findings bring into question assumptions about “normal” genital appearances.

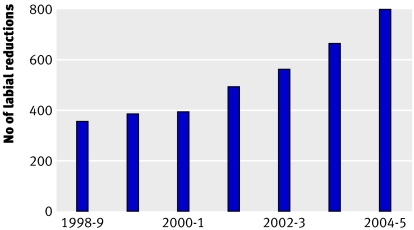

NHS stakeholders are unlikely to encourage demand for cosmetic genitoplasty, but availability in the private sector could put pressure on services and distort the allocation of resources. The doubling of the number of labial reductions in the past five years (figure) in the NHS suggests that this may already be happening.5

Number of labial reductions in the NHS

A non-evidence based practice

Most reports look only at technical aspects of surgery,6 7 8 and outcome data are sparse. Women are unlikely to admit to having had genital surgery, so that problems may go unreported. Psychological effects should also be thoroughly investigated because, even if an “abnormality” is clearly identified, the decision to have surgery always has a strong psychological basis. But few psychometrically robust measures exist to evaluate the long term impact of plastic surgery in general,9 let alone genital surgery. The few reports that exist on patients' satisfaction with labial reductions are generally positive, but assessments are short term and lack methodological rigour.10 11

In the absence of reliable evidence, guidelines have been produced for plastic surgery in the NHS.12 The Department of Health publication Plastic Surgery: Information for Patients offers specific guidance on surgery for labial reduction.13 However, there is no indication that practitioners adhere to guidelines.14 The apparent lack of interest in developing guidelines and collecting evidence about cosmetic genitoplasty has led some doctors to align the practice with “female genital mutilation.”15 The sentiment is not without justification when girls in their preteens are being operated on.10 11 Cosmetic genitoplasty is certainly challenging to arguments against medicalising even mild symbolic forms of female circumcision as a harm reduction strategy in some African countries.16 The lack of nuanced understanding of help seeking processes in our society precludes meaningful discussion about the benefits and harms of surgical solutions. It also hinders development of a wider range of solutions.

Most requests are for labial reduction, carried out by gynaecological or plastic surgeons in the NHS and private sector. Surgical incision to the labia carries risks. The labia minora contain many nerve fibres that are highly sensitive; during sexual arousal, they become engorged and everted and contribute to erotic sensation and pleasure.17 Some women request reduction of the clitoral prepuce or corpus. Research involving women with atypical genitalia (for whom genital surgery is common) has shown that clitoral surgery is associated with inability to reach orgasm.18 Furthermore, impaired sensitivity is specific to the site of surgery.19 Recent research has emphasised the role of the vulvar epithelium in sensuality and arousability.20 In other words, incision to any part of the genitalia could compromise sensitivity—an important aspect of sexual experience. So what makes women take such risks when their genital characteristics fall within typical ranges?

The current medical literature provides little help—reports focus mostly on anatomical outcomes of labial reduction using various surgical techniques. We therefore interviewed healthy adults who had undergone surgical reduction of normal labia, so that they could talk about their experience without undue concern about access to treatment. Our aim is to develop an informed research protocol with robust evaluation tools that can be used for women seeking cosmetic genital surgery in the NHS and the private sector. We were struck by our interviewees' ambivalence and struggle for clarity about their decision (see box).

Transcript extracts: a real dilemma

The decision about whether to undergo cosmetic surgery is said to be a dilemma for women as it is “problem and solution, oppression and liberation, all in one.”21 And so, despite their satisfaction with the treatment, most of our interviewees were hesitant about recommending it to other women. For example,

“There's a there's a there's a balance [ ] I would be interested actually to know how many women truly do need the operation out of all of us [research participants], because it would be interesting.”

“. . . if it's, purely [:] for cosmetic reasons and to me it looked, fine, I will have my doubts [:] I think it just varies, it's just, opinion.”

The need for the complaint to be real was thought to be an important basis for surgery, and what made it real was, firstly, the consistency with which it had troubled them and, secondly, when that trouble was physical,

“So I think you know sometimes you just have to be very careful. [:] You know when it's how someone sees themselves, or how they think, because then, you know that that can change with the wind, but if it's how they feel, based on a you know a physical feeling . . .''

or psychological,

“There need to be strong reasons, like in my case, when my partner comes near me, I want to avoid it [partner looking at her genitals] . . .”

In the absence of either physical or psychological unease, however, it was the psychologically arduous process—the “work” involved—in seeking help from “proper” NHS doctors that authenticated the preoperative complaint,

“. . . I thought, I've had to think about this, you know and I've had to [ ] [:] it's not, so it can just be oh I'm going I'm . . . Every other woman can say well I might as well have that done, I've had this done I've had that done I might as well have that done you know . . . it's the available thing isn't it . . . but once you've had to work to get it . . . You know to me, psychologically if you, if you go through the right channels [general practitioner and specialist] . . . rather than feeling that you can just, get it done just like that [:]. There's no understanding behind that is there?”

“True” needs and “untrue” needs cannot easily be separated in this context. The hesitancy of these otherwise articulate women may mirror that of surgeons who operate on women yet cannot reconcile their practice in principle or recommend it as policy.

These transcripts also suggest that genital surgery may be just one of a series of cosmetic operations in a woman's lifetime. One of the women had had breast augmentation to relieve her from “self consciousness.” Another one was saving for a “face lift.” One young woman had had her labia reduced at the age of 17 to stop her feeling anxious. However, she was still sexually anxious and avoided sex, so she was now seeking excision of her remaining labia. Like women born with atypical genitals, the surgical fix is so compelling that it can be difficult to explore the psychological basis for surgery beforehand, or even afterwards.22

Key to transcript notation: [ ]=noticeable pause; . . .=text omitted; [text]=text inserted by authors for clarification; text=said with emphasis; [:]=interviewer's minimal encouragers

A gendered desire

As in previous reports,2 10 11 our patients sometimes cited restrictions on lifestyle as reasons for their decision. These restrictions included inability to wear tight clothing, go to the beach, take communal showers, or ride a bicycle comfortably, or avoidance of some sexual practices. Men, however, do not usually want the size of their genitals reduced for such reasons. Furthermore, they find alternative solutions for any discomfort arising from rubbing or chaffing of the genitals.

Our patients uniformly wanted their vulvas to be flat with no protrusion beyond the labia majora, similar to the prepubescent aesthetic featured in advertisements.2 Not unlike presenting for a haircut at a salon, women often brought along images to illustrate the desired appearance. The illustrations, usually from advertisements or pornography, are always selective and possibly digitally altered.

There is nothing unusual about protrusion of the labia minora or clitoris beyond the labia majora. It is the negative meanings that make it into a problem—meanings that can give rise to physical, emotional, and behavioural reactions, such as discomfort, self disgust, perhaps avoidance of some activities, and a desire for a surgical fix.

A vicious cycle

The increased demand for cosmetic genitoplasty may reflect a narrow social definition of normal, or a confusion of what is normal and what is idealised. The provision of genitoplasty could narrow acceptable ranges further and increase the demand for surgery even more. More research is needed to learn about the social and psychological processes that have enabled many women to develop their own solutions to similarly negative preoccupations.

Resource issues aside, availability of surgical interventions could undermine the development of other ways to help women and girls to deal with concerns about their appearance in general. Surgery does not connect women with their ability to solve problems, with the result that some women just become preoccupied with the next “defect” to be fixed.

A questions for the NHS

Interventions that produce enduring psychological and functional benefits should not be dismissed. However, surgery is an extreme and unproved intervention in this instance, and it may not obviate the need for more specialist interventions. In the absence of local or national guidelines for surgeons, practice is likely to remain idiosyncratic.

Alleviation of suffering is fundamental to all healthcare professions, so who should tackle this emerging problem? When we reviewed general practitioners' letters of referral, we observed that they might have been unsure how to respond to their patients' intimate concerns without trivialising them. Some referrals may have been made in the hope that experts would persuade the woman that she was normal and deter her from surgery. But the lack of immediate reassurance and referral to a specialist might be interpreted as proof of the need for surgery. An increased desire for the longed for fix could subsequently compromise the patient's capacity to process information on risks and limitations about their desired intervention. Even with psychological expertise, the surgical context is unlikely to encourage women and girls to acknowledge and explore their struggles to develop a range of solutions. It should be thought of as the last resort, not the first port of call.

Multiagency initiatives involving health agencies, educational bodies, the voluntary sector, and the media are needed to help girls and women deal with feelings of insecurity about their genitals and about their bodies in general. We also need more commitment and investment in research as well as innovative interventions in the community to help women and girls to approach concerns about their appearance skilfully and imaginatively.

Summary points

Demand for cosmetic genitoplasty is increasing

Surgery carries risk and has not been shown to lead to enduring psychological or functional benefits

There should be increased awareness that the appearance of female genitals varies greatly

Solutions other than surgery are needed in response to girls' and women's concerns about their appearance, including that of their genitals

We are grateful to our patients and interviewees and to Naomi Crouch, Iain Morland, and Mary Boyle for their help and suggestions.

Funding: None.

Contributors and sources: LML is a consultant clinical psychologist with broad academic interests in women's health and she works clinically with adolescent and adult women with disorders of sex development. SMC is a consultant gynaecologist and a specialist in disorders of sex development and more broadly adolescent gynaecology.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Obtained from UCL and UCLH.

Provenance and peer review: Non-commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Braun V, Kitzinger C. The perfectible vagina: size matters. Culture Health Sexuality 2001;3:263-77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun V. In search of (better) sexual pleasure: female genital “cosmetic” surgery. Sexualities 2005;8:407-24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.British Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. 2007. Audit of surgical procedures. www.baaps.org.uk

- 4.Lloyd J, Crouch NS, Minto CL, Liao LM, Creighton SM. Female genital appearance: “normality” unfolds. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;112:643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Service. Hospital episode statistics 1999-2005 www.hesonline.nhs.uk

- 6.Alter GJ. A new technique for aesthetic labia minora reduction. Ann Plast Surg 1998;41:685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HY, Kim KT. A new method for aesthetic reduction of labia minora (the deepithelialized reduction of labioplasty). Plast Reconstruct Surg 2000;105:419-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maas SM, Hage JJ. Functional and aesthetic labia minora reduction. Plast Reconstruct Surg 2000;105:1453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cano SJ, Browne JP, Lamping DL. Patient-based measures of outcome in plastic surgery: current approaches and future directions. Br Assoc Plast Surg 2004;57:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouzier R, Louis-Sylvestre C, Paniel B-J, Haddad B. Hypertrophy of labia minora: experience with 163 reductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pardo J, Sola V, Ricci P, Guilloff E. Laser labioplasty of labia minora. Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;38-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Timmons MJ. Rationing of surgery in the National Health Service: the plastic surgery model. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000;82(suppl):332-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health. Cosmetic surgery: information for patients August 2006. www.dh.gov.uk/en/policyandguidance/healthandsocialcaretopics/cosmeticsurgery/index.htm

- 14.Cook SA, Rosser R, Meah S, James MI, Salmon P. Clinical decision guidelines for NHS cosmetic surgery: analysis of current limitations and recommendations for future development. Br Assoc Plast Surg 2003;56:429-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conroy RM. Female genital mutilation: whose problem, whose solution? BMJ 2006;333:106-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shell-Duncan B. The medicalization of “female circumcision”: harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice? Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1013-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman JR, Berman LA, Werbin TJ, Goldstein I. Female sexual dysfunction: anatomy, physiology, evaluation and treatment options. Curr Opin Urol 1991;9:563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minto CL, Liao LM, Woodhouse CRJ, Ransley PJ, Creighton SM. Adult outcomes of childhood clitoral surgery for ambiguous genitalia. Lancet 2003;361:1252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crouch NS, Minto CL, Laio LM, Woodhouse CRJ, Creighton SM. Genital sensation following feminising genitoplasty for congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a pilot study. Br J Urol Int 2004;93:135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin-Alguacil N, Schober JM, Kow L-M, Pfaff DW. Arousing properties of vulvar epithelium. J Urol 2006;176:456-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis K. Reshaping the female body: dilemma of cosmetic surgery London: Routledge, 1995

- 22.Boyle M, Smith S, Liao LM. Adult genital surgery for intersex women: a solution to what problem? J Health Psychol 2005;10:573-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]