Abstract

Fibroblast cooperation with cancer cells in xenograft development was investigated by transplanting MDA-MB-231 cells under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice. Control fibroblasts and fibroblasts subjected to stress-induced premature senescence by treatment with bleomycin were used. In other xenograft models, senescent fibroblasts have shown a growth-stimulatory effect greater than that of control cells. In this model, both types of fibroblasts accelerated the formation and growth of xenografts. Blood vessel development, as evidence by von Willebrand factor staining, was greatly accelerated by the presence of fibroblasts, and invasion into the kidney was also increased. Control and senescent fibroblasts had very similar effects. These actions of fibroblasts were partially recapitulated in in vitro experiments. Both control and senescent fibroblasts stimulated the tubulogenesis of endothelial cells in culture and stimulated the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells through Matrigel in vitro. In this xenograft model, in which fibroblasts are cotransplanted with a cancer cell into an internal organ rather than subcutaneously, senescence was not an important factor in the effects of cotransplanted fibroblasts on growth, blood vessel development, and invasion. Therefore, cancer promotion by the senescence of adjacent stromal cells may be restricted to certain organ and tissue types.

Keywords: Senescence, cancer cell xenografts, immunodeficient mice, stroma, subrenal capsule

Introduction

Xenografts of human cancer cells in immunodeficient mice have been used extensively to probe the behavior of human cells in an in vivo environment. Although xenografts are most frequently grown subcutaneously in mice, other ectopic or orthotopic sites in the body have often been used because these sites support more rapid growth and vascularization of cancer cells, and/or support more invasion and metastasis. In particular, the space beneath the kidney capsule has been extensively used for cell and tissue transplantation. In early experiments, an assay for the growth of primary human tumors was developed using the subrenal capsule space [1]. Following the success of the growth of solid tumor fragments in the kidney, the technique was adapted for cultured cells by embedding them in a fibrin clot before inserting them under the kidney capsule [2]. More recently, the subrenal capsule space has been used for tissue recombination and reconstruction, as applied to breast and prostate tissues [3,4]. However, even before these techniques were introduced, it had already been demonstrated that cancer cells form xenografts when injected as cell suspensions beneath the kidney capsule [5,6]. Our studies on adrenocortical cells showed that injection of cells under the kidney capsule was ideal for cell survival, permitting functional vascularized tissue formation from normal primary cells [7–9]. Although the subrenal capsule site is an ectopic site for non-kidney-derived cells, cancers (such as breast and prostate cancers) grown in this site acquire histologic features characteristic of these cancers in their orthotopic sites [10,11].

The excellent survival and growth of cells in this site are usually attributed to the unique features of the renal vasculature. The kidney has a very high level of blood flow, a positive interstitial fluid pressure, and a high rate of lymph flow [12,13]. The net effect of this combination of features is that there is exceptional fluid circulation within the extracellular space of the kidney; every 5 to 6 seconds, fluid equaling its entire volume passes through the interstitium [13]. Before transplanted cells and tissues become vascularized, whether situated beneath the kidney capsule or situated elsewhere in the body, an abundant supply of extracellular fluid supplying nutrients and oxygen is likely critical to the success of the transplant [14]. Thus, conventional blood supply to the kidney is important for the early survival of transplanted cells; however, the arterial supply to cells and tissues transplanted beneath the kidney capsule appears to comprise predominantly collateral arteries that supply the capsule [15].

The present approach is part of a systematic study of the features of the subrenal capsule site that make it an excellent environment for xenograft growth and to compare the behavior of cells in this site with the behavior of cells transplanted subcutaneously [16]. One specific aspect is the role of cotransplanted mesenchymal cells, which may assist the survival and growth of cancer and normal cells in this site [4,7–10,17].

In subcutaneous xenograft models, senescence is an important factor for the promoting effect of cotransplanted fibroblasts in cancer xenograft growth [18]. In this site in the body, senescent cell products, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), assist the survival and growth of cotransplanted cancer cells, such as the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 [16,18]. Senescence, which is the terminal state of cells that have sustained unrepairable DNA damage, exerts a tumor-suppressor effect on cells that undergo senescence but can exert a procancer effect on neighboring cells through secreted senescence-specific products [19]. The extent to which senescent cells exert such a protumorigenic effect in vivo is as yet unknown, and models that explore the potential importance of senescence in sites other than the subcutaneous site are needed.

Our aims in the present set of experiments were to: 1) make a reproducible subrenal capsule xenograft model using MDA-MB-231 cells; and 2) use this model to examine whether senescence is an important factor in fibroblast-assisted xenograft growth as it is in subcutaneous xenograft models. In xenograft experiments, the earliest phases of the development of the transplant following cell implantation have not often been studied. Based on prior data on the early phases of the development of cell transplants [14], we hypothesized that it would be especially important to study the early stages of xenograft development.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Normal human newborn foreskin fibroblasts (HCA2) were obtained from Dr. Olivia Pereira-Smith (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX). The human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 was obtained from Dr. Judith Campisi (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing MDA231 cells were obtained by transfection with plasmid pEGFP-N1 (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Fibroblasts and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Cosmic Calf Serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Clonetics brand; Lonza Bioscience, Walkersville, MD) were used within seven passages of receipt. GFP-expressing HUVECs were obtained by transduction with retrovirus pLEGFP-N1 (BD Biosciences Clontech). All experiments employing HUVECs were performed in EGM-2 medium (Clonetics brand; Lonza Bioscience) supplemented with 50 ng/ml vascular endothelial growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Preparation of Stress-Induced Premature Senescence (SIPS) Fibroblasts

Senescence was induced in HCA2 fibroblasts by incubation in 10 µg/ml bleomycin sulfate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) for 24 hours [20–22]. Following this treatment, cells were observed to have an enlarged, flattened, senescence-like morphology. Senescence was evidenced by plating cells at low density and by demonstrating the absence of colony growth, and was also assessed by senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining [23]. SIPS fibroblasts were used for experiments after 7 days of incubation in regular medium following 24 hours of incubation in bleomycin. The medium was changed four times over this period to remove all free bleomycin.

Xenografts in Immunodeficient Mice

RAG2-/-γc-/- mice originally purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY) were maintained in an animal barrier facility as a breeding colony. Animals (both males and females) at the age of > 6 weeks (∼ 25 g body weight) were used in these experiments. Procedures were approved by the institutional animal care committee and were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Cell transplantation was performed under tribromoethanol anesthesia [24]. An oblique incision (< 1 cm) was made on the skin parallel and adjacent to the long axis of the left kidney. Cells to be implanted were trypsinized and resuspended in cold culture medium. The total volume (cells and medium) was 10 to 15 µl. Cells were injected under the kidney capsule with a blunt 25-gauge needle and a glass Hamilton syringe using a transrenal injection. The kidney was returned to the retroperitoneal space. The skin was closed with surgical staples.

Postoperative care for the animals, including the administration of analgesics and antibiotics, was performed as previously described [24]. Animals were sacrificed at various times following cell transplantation, as described in Results. GFP-expressing tumors were photographed under the illumination of a 470-nm light (Lightools Research, Encinitas, CA).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Xenografts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed conventionally. For staining against von Willebrand factor (vWf), deparaffinized sections were pretreated with 50 µg/ml proteinase K for 15 minutes at room temperature. They were then incubated with a 1:500 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-human vWf antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Bound antibody was visualized with biotinylated universal secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Staining was developed with diaminobenzidine substrate, and sections were counterstained with dilute hematoxylin. To quantitate vessel formation, the length of vWf+ vessels was measured on photographs of sections using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA).

An index of invasion was calculated based on measurements made on hematoxylin/eosin-stained sections. Photographs were analyzed using Photoshop software. The length of the boundary between the tumor tissue and the kidney parenchyma (b) and the width of the section (w) was measured. The invasion index was calculated as: (b - w)/w.

Tubulogenesis Assay

Endothelial cells undergo tubulogenesis in the presence of cocultured fibroblasts [25]. SIPS or control HCA2 fibroblasts (2 x 105) were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 4 hours, 105 HUVECs were plated on top of fibroblast lawns. At various times, cultures were photographed by fluorescence microscopy; for this purpose, GFP-expressing HUVECs were used. At later time points, coverslip cultures were fixed in 70% cold ethanol. Tubule formation was visualized by staining with anti-vWf antibody (Dako). Blocking was achieved by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin, and fixed cultures were incubated with 1:400 anti-vWf, followed by incubation with biotinylated universal secondary antibody (Vector) and development with diaminobenzidine substrate. Stained areas, which represent the extent of tubule formation, were quantitated on randomly selected fields using Photoshop software.

Cell Culture Invasion Assay

Control or SIPS fibroblasts were incubated with serum-containing culture medium for 24 hours. Control fibroblasts were plated at high density, so that no significant proliferation over 24 hours was observed. Conditioned medium was collected for use in an invasion assay (Matrigel Invasion Chamber; Becton Dickinson). GFP-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells (105 cells) were plated on the upper surface of Matrigel-coated inserts. The conditioned medium was added to the upper chamber, and DMEM with 5% fetal bovine serum was added to the lower chamber. After 22 hours, MDA-MB-231 cells that had migrated through the membrane to the lower surface were counted using fluorescence microscopy.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between groups.

Results

Fibroblasts Accelerate Xenograft Formation following Transplantation of MDA-MB-231 Cancer Cells under the Kidney Capsule

MDA-MB-231 cells were transplanted under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice, either alone or together with normal human fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were either untreated or subjected to SIPS by treatment with bleomycin. Five days following cell transplantation, MDA-MB-231 cells injected alone under the kidney capsule formed a mass of loosely attached cells, and there was prominent fluid accumulation (Figure 1). Some cells attached to the kidney, and others attached to the distended capsule. In contrast, the inclusion of normal human fibroblasts, together with MDA-MB-231 cells, resulted in the formation of a much more solid tissue structure, with little or no fluid accumulation and no distension of the capsule. There was no discernable difference between the appearance of xenografts formed with SIPS fibroblasts and the appearance of xenografts formed with control fibroblasts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subrenal capsule xenograft growth with and without cotransplanted fibroblasts. MDA-MB-231 cells (2 x 106) were injected under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice, alone or with 2 x 106 HCA2 human fibroblasts. Control fibroblasts (CF) and fibroblasts that have undergone stress-induced premature senescence (SF) were used. NF = no fibroblasts. The histology of xenotransplants is shown at 5 days (5NF, 5CF, and 5SF), 9 days (9NF, 9CF, and 9SF), and 15 days (15NF, 15CF, and 15SF) following cell transplantation. Four examples of 9-day CF and SF transplants are shown to demonstrate the reproducibility of this model when cotransplanted fibroblasts are used (see text). Hematoxylin/eosin stain. Original magnification, x40.

Nine days following cell transplantation, the xenografts were larger than they were at 5 days (Figure 2). Most of the fluid noticed at 5 days was no longer observed. Xenografts of MDA-MB-231 cells alone were much smaller than those formed with fibroblasts. This trend continued up to 15 days. It was important to demonstrate the reproducibility of this cotransplant xenograft model so that the effects of fibroblasts (control or SIPS) could be precisely assessed. We found that 9-day xenografts formed from cotransplants of MDA-MB-231 cells and fibroblasts were very reproducible; four examples of each type (control and SIPS fibroblasts) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Growth of subrenal capsule xenografts with and without cotransplanted fibroblasts. The sizes of xenografts were calculated from histologic sections of samples from animals sacrificed at 5 and 9 days following cell transplantation (five mice per group). Open bar: 2 x 106 MDA-MB-231 cells, no fibroblasts. First hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with 2 x 106 control fibroblasts. Second hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with SIPS fibroblasts. Values found to be statistically different are indicated together with the P value (ANOVA).

At 15 days, xenografts containing fibroblasts had grown extensively, and much of the kidney had been destroyed. MDA-MB-231 cells also invaded into the kidney but, at 15 days, had grown much less extensively than xenografts with fibroblasts.

Fibroblasts Increase the Density of Blood Vessels in Subrenal Capsule MDA-MB-231 Cell Xenografts

At 5 days, xenografts of MDA-MB-231 cells, with or without fibroblasts, appeared as white masses under the kidney capsule. Surface blood vessels were not apparent. At 9 days, many blood vessels were observable in the capsule (Figure 3). These vessels were observed in xenografts formed by MDA-MB-231 cells alone and in xenografts formed with cotransplanted control and SIPS fibroblasts. These blood vessels supplying the xenografts appear to be enlarged collateral vessels that normally supply the capsule. They are usually not visible but become greatly enlarged in the region of the capsule overlying the xenografts.

Figure 3.

Enlargement of blood vessels within the kidney capsule overlying xenografts. GFP-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells were transplanted under the kidney capsule. (A and A′) 2 x 106 MDA-MB-231 cells alone. (B and BV) MDA-MB-231 cells with 2 x 106 control fibroblasts. (C and C′) MDA-MB-231 cells with SIPS fibroblasts. At 9 days, prominent blood vessels were observed in the capsule. (A–C) Surface appearance. (A′–C′) Appearance under blue light illumination; the xenograft is fluorescent, and blood vessels appear dark. Original magnification, x20.

Although vessels supplying the capsule enlarged in all xenografts at ∼ 9 days, we observed differences in the formation of capillaries and larger vessels within the xenografts. The density of newly formed blood vessels in the xenografts was measured. Vessels were visualized by staining endothelial cells for vWf. The length of vessels per unit area was measured. Xenografts containing fibroblasts exhibited a density of vessels much greater than those formed without fibroblasts (Figure 4). Xenografts formed with SIPS fibroblasts did not differ in vessel density from those formed with control fibroblasts.

Figure 4.

Development of blood vessels in xenografts. MDA-MB-231 cells were transplanted under the kidney capsule: (A) 2 x 106 cells alone. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells with 2 x 106 control fibroblasts. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells with SIPS fibroblasts. At 9 days, samples were taken for immunohistochemistry. Sections were stained with an antibody against vWf. Original magnification, x 150. (D) The length of vWf + vessels was measured in antibody-stained sections (five mice per group). Open bar: MDA-MB-231 cells, no fibroblasts. First hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with control fibroblasts. Second hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with SIPS fibroblasts. Values found to be statistically different are indicated together with the P value (ANOVA).

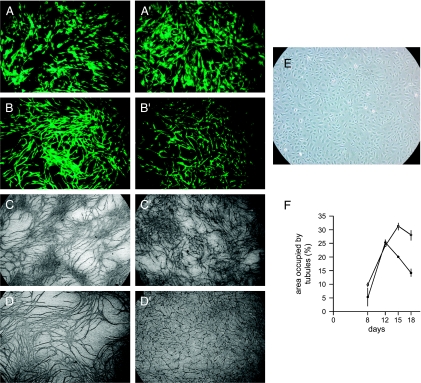

We investigated whether the effects of fibroblasts observed in MDA-MB-231 xenografts could be reproduced in studies in vitro. To examine effects on vessel formation, we used tubulogenesis in endothelial cell cultures. Under appropriate conditions in culture, endothelial cells form tubules, a process thought to be the equivalent of capillary formation in vivo [25]. Fibroblasts were plated in culture to form confluent lawns. Endothelial cells were then plated on top of the fibroblasts or plated onto polystyrene tissue culture dishes without fibroblasts. We used HUVECs that had been infected with a retrovirus encoding GFP to enable them to be distinguished from fibroblasts. Cultures were photographed at various times to examine tubule formation or were fixed and stained with an anti-vWf antibody. On plastic tissue culture dishes without fibroblasts, endothelial cells failed to form tubules. When plated on fibroblasts, endothelial cells formed tubules that were visible both by GFP fluorescence and by vWf staining (Figure 5). In the initial period, there were no consistent differences between control and SIPS fibroblasts. At later times (> 12 days), tubules that had formed on SIPS fibroblast lawns showed a greater tendency to disintegrate, whereas this was not as prominent in tubules formed on control fibroblast lawns. We quantitated tubule formation at various times. Up to 12 days, both control and SIPS fibroblasts supported the development of tubules from endothelial cells. After this time, tubules were stable on control fibroblasts but decreased by up to 50% on SIPS fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

Effects of fibroblasts on tubulogenesis in culture. GFP-expressing HUVECs were plated either alone (105 cells) or onto lawns of human fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were untreated or had been treated to cause SIPS. The medium used is described in Materials and Methods. HUVECs cultured on fibroblast lawns formed tubules. (A and B) At early times after plating, fluorescence microscopy was used to observe HUVEC growth patterns (A and B, control fibroblasts; A′ and B′, SIPS fibroblasts; A = 2 days; B = 5 days; original magnification, x 15). (C and D) At later time points, vWF staining was used to visualize tubules. (C and D) Control fibroblasts. (C′ and D′) SIPS fibroblasts (C = 12 days; D = 18 days; original magnification, x8). (E) HUVECs cultured alone did not form tubules (phase contrast; original magnification, x20). (F) The area occupied by tubules in culture was measured at 8, 12, 15, and 18 days. Open symbols: HUVECs plated on control fibroblasts. Closed symbols: HUVECs plated on SIPS fibroblasts. Each group comprised three replicates; the experiment was repeated thrice with similar results.

Fibroblasts Increase the Invasiveness of Xenografts

To assess the degree of invasion of xenograft cells into the kidney, we measured the length of the boundary between the tumor tissue and the kidney tissue. The shortest boundary, a straight line, would be formed by tissue that did not, in any way, invade the kidney. To the extent that the length of the boundary exceeds that of a straight line, it can be used as an index of increasing invasiveness. We chose 9 days as the stage of xenograft development during which some invasion has started to take place yet the boundary is still clearly visible. At later times, extensive destruction of the kidney caused by tumor growth made assessment of the location of the xenograft boundary difficult. At 9 days, invasiveness was higher in xenografts formed with fibroblasts than in those formed without fibroblasts (Figure 6). Xenografts formed with SIPS fibroblasts showed invasiveness similar to that of xenografts formed with control fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells into the host kidney. MDA-MB-231 cells were transplanted under the kidney capsule alone (2 x 106 cells) or with 2 x 106 control fibroblasts or SIPS fibroblasts. At 5 and 9 days, samples were taken for histologic examination. (A–C) The appearance of the border between MDA-MB-231 cells and the kidney in xenografts without fibroblasts (A) and in xenografts with control fibroblasts (B) or SIPS fibroblasts (C). Original magnification, x400. (D) Using the procedure described in Materials and Methods, the invasion index was calculated for 5- and 9-day xenografts, with and without fibroblasts. Open bar: MDA-MB-231 cells, no fibroblasts. First hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with control fibroblasts. Second hatched bar: MDA-MB-231 cells with SIPS fibroblasts. Values found to be statistically different are indicated together with the P value. (E) Fibroblast effects on MDA-MB-231 cell invasion in vitro. MDA-MB-231 cells were plated on Matrigel-coated membranes. After 24 hours, the number of cells that had penetrated the membrane was measured (three measurements per group). Experiments were performed with nonconditioned medium (open bar) or in the presence of conditioned medium from control fibroblasts (first hatched bar) or SIPS fibroblasts (second hatched bar). Values found to be statistically different are indicated together with the P value (ANOVA).

We were interested to understand whether the increased invasiveness resulted from factors produced by fibroblasts that altered the behavior of cancer cells in culture. To study this, MDA-MB-231 cells were plated on Matrigel-coated membranes, and medium that had been conditioned by fibroblasts was added. The fibroblast-conditioned medium caused a marked increase in the number of MDA-MB-231 cells that migrated through the membrane (Figure 6E). The medium from SIPS fibroblasts was, however, less effective than the medium from control fibroblasts.

Discussion

The interaction of stromal and cancer cells in cancer growth and malignant properties is recognized as a critically important factor in tumorigenesis [26–31]. One established method for investigating stromal-cancer cell interactions is the creation of xenografts from mixed cell populations. Interestingly, in xenografts formed from mixed populations of cancer cells and human fibroblasts, senescence of cotransplanted fibroblasts has been found to increase stimulatory effects on cancer growth [16,18]. These studies have been performed in subcutaneous cell transplantation experiments.We hypothesized that it would be important to understand the potential effects of cotransplanted fibroblasts in xenograft growth in an internal organ, the kidney, using the subrenal capsule space, an excellent site for cancer cell growth.

To make a quantitative assessment of whether senescence of fibroblasts affects cancer cell growth and properties, it is necessary to have a reproducible and simple model for xenograft development. We show here that the subrenal capsule xenograft model is highly reproducible. Therefore, relatively small effects of senescent versus control fibroblasts would be detected. Although the inclusion of fibroblasts greatly accelerated the formation of subrenal capsule xenografts, careful measurements showed no effect of senescence on the fibroblast effect. This lack of effect was not the result of a failure of senescent cells to acquire growth-stimulating properties. We have shown that bleomycin-treated HCA2 human fibroblasts, the SIPS model used here, caused a selective increase in MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth, in comparison to control fibroblasts, when cells are cotransplanted subcutaneously [16]. Additionally, they exhibited dramatic changes in gene expression patterns characteristic of senescence [16]. Thus, we conclude that senescence-specific products such as MMPs or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which mediate the effects of senescent cells subcutaneously, are not involved in the effects of fibroblasts in the kidney model.

There are a variety of differences in the two sites (subcutaneous and subrenal capsule) that probably account for these differences. As noted above, the subrenal capsule site has a very high rate of interstitial fluid flow. However, in the loose connective tissue under the skin, into which cells are traditionally implanted for xenograft studies, there is a much lower rate of interstitial fluid flow. Here senescent cell-derived products such as MMPs may cause increased capillary permeability and interstitial fluid accumulation [16]. In the kidney, the actions of cotransplanted senescent cells probably do not affect the already abundant interstitial fluid flow. Moreover, the abundant interstitial fluid flow might rapidly clear fibroblast-secreted products in this site.

Although senescence was not a factor in xenograft growth, the presence of fibroblasts, both control and SIPS, greatly accelerated the development of xenografts. The acceleration of growth by fibroblasts has been previously observed in subrenal capsule xenografts [4,10,17]; these studies used control fibroblasts and did not specifically examine the effects of senescence. We noted here that, in the absence of fibroblasts, there was an early split of the kidney capsule away from the xenograft. The major action of fibroblasts was to consolidate the transplant and to prevent the splitting of the capsule away from the xenograft. The mode of action of the fibroblasts in this model is not known. More studies are required to examine whether the effect is dependent on cell-cell contact, on fibroblast products such as extracellular matrix components, or on paracrine mediators.

We observed that the accelerated growth of xenografts was accompanied by an earlier invasion of cancer cells into the kidney. The subrenal capsule site readily allows the invasive characteristics of cancer cells to be observed [32,33]. Malignant tissues that invade into the kidney from a subcapsular transplant become thoroughly interspersed in the kidney parenchyma. Glomeruli and tubules are often found to be surrounded by invading cancer tissues. However, normal tissues in the same subrenal capsule site maintain a clear and relatively straight boundary between the transplant tissue and the kidney parenchyma [7–9,32]. In the present experiments, both normal and senescent fibroblasts increased early invasion, although eventually all xenografts completely invaded and destroyed the kidney. We investigated whether the stimulatory effect appeared to be caused by a secreted fibroblast product. In culture, conditioned medium from both control and senescent fibroblasts increased the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells through a Matrigel-coated membrane. The effect of conditioned medium from control fibroblasts was greater; however, in the kidney, the stimulatory effects of control and senescent fibroblasts were indistinguishable. This suggests a negative effect of a senescent cell-specific product, but further study will be needed to elucidate the reason for the difference.

The subrenal capsule site also allows the development of new blood vessels in the cancer tissue to be readily observed. Vessel development in cancers proceeds through angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, and vessel cooption [34]. In these experiments, we observed that the accelerated growth of xenografts in the presence of fibroblasts was accompanied by an increased density of vWf+ capillaries. As we also observed for invasion, there was no distinguishable difference between control and senescent fibroblasts in the stimulation of vessel density. Nevertheless, in culture, we noted differences in the tubulogenesis of endothelial cells growing on lawns of control or senescent fibroblasts. HUVECs did not form tubules when grown on tissue culture plastic, but the growth of endothelial cells on both types of fibroblasts resulted in extensive tubule formation. However, tubules showed a tendency to disintegrate after several days, which was not observed in tubules formed on control fibroblasts. Factors specifically secreted by senescent fibroblasts could have a long-term negative effect on tubulogenesis [35], but further studies are needed to elucidate this effect. We conclude that both types of fibroblasts stimulate tubulogenesis but that a senescent-specific factor causes tubule instability.

Overall, in these experiments, we noted that there was an imperfect correlation between fibroblast effects observed in culture and their behavior in a well-characterized and reproducible xenograft model in the mouse. These data indicate that caution must be exercised in interpreting culture models in terms of cancer biology in vivo. Whereas in vitro models allow high-throughput screening and detailed investigations of molecular mechanisms, appropriate validation of findings in animal models is always required. The lack of effect of senescence in the subrenal capsule xenograft model suggests that cancer promotion by the senescence of adjacent stromal cells may be restricted to certain organ and tissue types.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG12287 and AG20752) and by a Senior Scholar Award from the Ellison Medical Foundation. Support by the San Antonio Cancer Institute Cancer Center (P30 CA54174) is also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Bogden AE, Kelton DE, Cobb WR, Esber HJ. A rapid screening method for testing chemotherapeutic agents against human tumor xenografts. In: Houchens DP, Ovejera AA, editors. Proceedings of the Symposium on the Use of Athymic (Nude) Mice in Cancer Research; Gustav Fischer; New York. 1978. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fingert HJ, Chen Z, Mizrahi N, Gajewski WH, Bamberg MP, Kradin RL. Rapid growth of human cancer cells in a mouse model with fibrin clot subrenal capsule assay. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3824–3829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayward SW, Haughney PC, Rosen MA, Greulich KM, Weier HU, Dahiya R, Cunha GR. Interactions between adult human prostatic epithelium and rat urogenital sinus mesenchyme in a tissue recombination model. Differentiation. 1998;63:131–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1998.6330131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salup RR, Herberman RB, Wiltrout RH. Role of natural killer activity in development of spontaneous metastases in murine renal cancer. J Urol. 1985;134:1236–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47702-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naito S, von Eschenbach AC, Giavazzi R, Fidler IJ. Growth and metastasis of tumor cells isolated from a human renal cell carcinoma implanted into different organs of nude mice. Cancer Res. 1986;46:4109–4115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas M, Northrup SR, Hornsby PJ. Adrenocortical tissue formed by transplantation of normal clones of bovine adrenocortical cells in scid mice replaces the essential functions of the animals' adrenal glands. Nat Med. 1997;3:978–983. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas M, Yang L, Hornsby PJ. Formation of functional tissue from transplanted adrenocortical cells expressing telomerase reverse transcriptase. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:39–42. doi: 10.1038/71894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas M, Wang X, Hornsby PJ. Human adrenocortical cell xenotransplantation: model of cotransplantation of human adrenocortical cells and 3T3 cells in scid mice to form vascularized functional tissue and prevent adrenal insufficiency. Xenotransplantation. 2002;9:58–67. doi: 10.1046/j.0908-665x.2001.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar H, Young P, Emerman JT, Neve RM, Dairkee S, Cunha GR. A novel method for growing human breast epithelium in vivo using mouse and human mammary fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4886–4896. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii K, Shappell SB, Matusik RJ, Hayward SW. Use of tissue recombination to predict phenotypes of transgenic mouse models of prostate carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1086–1103. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott CE, Knox FG. Tissue pressures and fluid dynamics in the kidney. Fed Proc. 1976;35:1872–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinter GG. Renal lymph: vital for the kidney and valuable for the physiologist. News Physiol Sci. 1988;3:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunstead JR, Thomas M, Hornsby PJ. Early events in the formation of a tissue structure from dispersed bovine adrenocortical cells following transplantation into scid mice. J Mol Med. 1999;77:666–676. doi: 10.1007/s001099900040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornsby PJ, Thomas M. Cell transplantation: a new technique to study the biology of the adrenal cortex. In: Okamoto M, Ishimura Y, Nawata H, editors. Molecular Steroidogenesis. Tokyo: Universal Academy Press; 2000. pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu D, Hornsby PJ. Senescent human fibroblasts increase the early growth of xenograft tumors via matrix metalloproteinase secretion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3117–3126. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koldovsky P, Haas I, Ganzer U. Promoting effects of fibroblasts on growth and progression of head and neck carcinoma cells. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996;58:248–252. doi: 10.1159/000276847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumori-genesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12072–12077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211053698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robles SJ, Adami GR. Agents that cause DNA double strand breaks lead to p16(INK4A) enrichment and the premature senescence of normal fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1998;16:1113–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–747. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bavik C, Coleman I, Dean JP, Knudsen B, Plymate S, Nelson PS. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2006;66:794–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimri GP, Lee XH, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott C, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith OM, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas M, Hornsby PJ. Transplantation of primary bovine adrenocortical cells into scid mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;153:125–136. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop ET, Bell GT, Bloor S, Broom IJ, Hendry NF, Wheatley DN. An in vitro model of angiogenesis: basic features. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:335–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1026546219962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elenbaas B, Weinberg RA. Heterotypic signaling between epithelial tumor cells and fibroblasts in carcinoma formation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:169–184. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tlsty TD, Hein PW. Know thy neighbor: stromal cells can contribute oncogenic signals. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch CC, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor - host cell communication. Differentiation. 2002;70:561–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Kempen LC, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GN, Coussens LM. The tumor microenvironment: a critical determinant of neoplastic evolution. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82:539–548. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang Y, Nakada MT, Kesavan P, McCabe F, Millar H, Rafferty P, Bugelski P, Yan L. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer stimulates tumor angiogenesis by elevating vascular endothelial cell growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3193–3199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun B, Huang Q, Liu S, Chen M, Hawks CL, Wang L, Zhang C, Hornsby PJ. Progressive loss of malignant behavior in telomerase-negative tumorigenic adrenocortical cells and restoration of tumorigenicity by human telomerase reverse transcriptase. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6144–6151. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun B, Chen M, Hawks CL, Pereira-Smith OM, Hornsby PJ. The minimal set of genetic alterations required for conversion of primary human fibroblasts to cancer cells in the subrenal capsule assay. Neoplasia. 2005;7:585–593. doi: 10.1593/neo.05172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim ES, Serur A, Huang J, Manley CA, McCrudden KW, Frischer JS, Soffer SZ, Ring L, New T, Zabski S, et al. Potent VEGF blockade causes regression of coopted vessels in a model of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11399–11404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwarze SR, Fu VX, Desotelle JA, Kenowski ML, Jarrard DF. The identification of senescence-specific genes during the induction of senescence in prostate cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2005;7:816–823. doi: 10.1593/neo.05250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]