Abstract

Although significant progress has been achieved in understanding the genetic and biochemical bases of the spore germination process, the structural basis for breaking the dormant spore state remains poorly understood. We have used atomic force microscopy (AFM) to probe the high-resolution structural dynamics of single Bacillus atrophaeus spores germinating under native conditions. Here, we show that AFM can reveal previously unrecognized germination-induced alterations in spore coat architecture and topology as well as the disassembly of outer spore coat rodlet structures. These results and previous studies in other microorganisms suggest that the spore coat rodlets are structurally similar to amyloid fibrils. AFM analysis of the nascent surface of the emerging germ cell revealed a porous network of peptidoglycan fibers. The results are consistent with a honeycomb model structure for synthetic peptidoglycan oligomers determined by NMR. AFM is a promising experimental tool for investigating the morphogenesis of spore germination and cell wall peptidoglycan structure.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, cell wall, germination, amyloid, peptidoglycan

When starved for nutrients, Bacillus and Clostridium cells initiate a series of genetic, biochemical, and structural events that result in the formation of a metabolically dormant endospore (1). Spores can remain dormant for extended time periods and possess a remarkable resistance to environmental insults (i.e., heat, radiation, toxic chemicals, and pH extremes) (1–5) that are lethal to vegetative cells. The resistance and persistence of dormant spores is attributed to a multilayer spore architecture (6). Upon exposure to favorable conditions, spores break dormancy through the process of germination (2, 7, 8) and eventually reenter the vegetative mode of replication.

A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms controlling spore germination is of fundamental importance both for practical applications related to the prevention of a wide range of diseases by spore-forming bacteria (including food poisoning and pulmonary anthrax), as well as for fundamental studies of cell development. Germination involves an ordered sequence of chemical, degradative, biosynthetic, and genetic events (2, 8).

Significant progress has been made in understanding the biochemical and genetic bases for the germination process (2). Germination is triggered by the interaction of germinants with specific receptors (2, 7, 9) in the inner spore core membrane, causing the release of the dipicolinic acid and its replacement by water. Subsequent hydrolysis of the spore cortex, further uptake of water, core expansion, and spore coat hydrolysis allow emergence of the incipient vegetative cell.

The role of the spore coat in the germination process is unclear (2, 6) and is the focus of this study. Spore coat structure regulates the permeation of germinant molecules (7–10). It is believed that penetration of germinants proceeds through pores in the coat structure and may involve GerP proteins (9).

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been used to probe in vitro the architecture of large macromolecular ensembles and pathogens (reviewed in ref. 11). In particular, high-resolution AFM studies of fungal spores (12, 13) have revealed native spore coat structure and surface adhesion properties accompanying spore germination (12). We have used AFM to investigate spore coat structure and assembly mechanisms in several species of Bacillus (14–16). We have also used AFM to study environmental effects on the structural dynamics of single ungerminated spores (14, 16). Whereas AFM images of air-dried germinated Bacillus spores have been reported (17, 18), high-resolution spore coat structures were not resolved. Here, we report the development of in vitro AFM methods for molecular-scale examination of spore coat and germ cell wall dynamics during spore germination and outgrowth.

Results

Spore Germination: Spore Coat Architecture and Dynamics.

In the present study, the germination of single Bacillus atrophaeus spores was investigated. At the micrometer scale, when spores are exposed to cognate germinant molecules, germination initiates with an increase in spore volume resulting from the uptake of water and terminates with the release of emerging vegetative cells from spore coat remnants (19). The timing of germination and outgrowth varies stochastically among individual spores (20). The germination medium used for our germination experiments was designed to allow rapid and synchronous initiation of spore germination, but does not have sufficient nutritional resources to allow extensive vegetative cell outgrowth. Preliminary high-resolution AFM analysis of B. atrophaeus spores germinating in this medium indicated that swelling occurred within 0.5 h of germinant contact. Initiation of etching of the coat layers and outgrowth typically occurred within 1–2 h and 3–7 h, respectively (data not shown), which allows successful real-time AFM visualization of the germination and outgrowth process. Individual germinating spores were followed in real time to probe molecular-scale structural transformations and to construct a complete cytological sequence of the germination process.

A significant fraction (≈30%) of spores did not proceed to outgrowth in the timeframe of the observation and did not exhibit degradation of the rodlet layer. However, after drying, >90% of these spores showed a structural collapse, indicating the prior replacement of dipicolinic acid in the spore core with water, i.e., they did proceed through the germination stage, but not to the outgrowth stage.

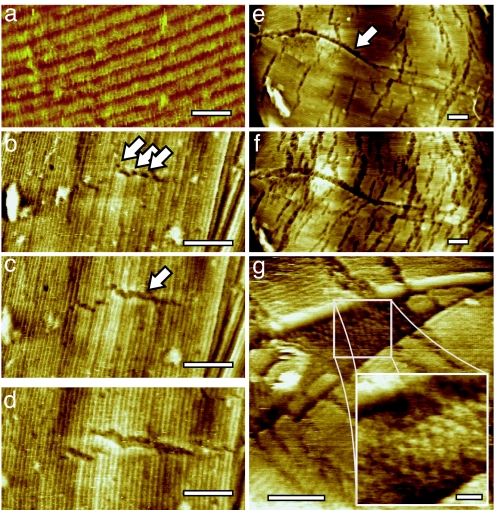

To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the role of the spore coat in germination, AFM imaging on a nanometer scale is required. At this scale, the outer layer of the B. atrophaeus spore coat is composed of a crystalline rodlet array (14) (Fig. 1a) containing a small number of point and planar (stacking fault) defects (16). Upon exposure to the germination solution, disassembly of the rodlet structures was observed on ≈70% of spores. During the initial stages of germination, the formation of 2- to 3-nm-wide micro-etch pits in the rodlet layer was observed (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, the etch pits formed fissures (Fig. 1 b–d) that were, in all cases, oriented perpendicular to the rodlet direction. Simultaneously, etching commenced on the stacking faults (Fig. 1 e and f) revealing a previously unrecognized spore coat layer with a hexagonal structure (Fig. 1g). During later stages of germination, further disintegration of the rodlet layer (Fig. 1 e and f) proceeded by coalescence of existing fissures, their autonomous elongation (at a rate of ≈10–15 nm/hr) and widening (at ≈5 nm/hr), and by continued formation of new fissures.

Fig. 1.

Disintegration of the spore coat rodlet layer. (a) The intact rodlet layer covering the outer coat of dormant B. atrophaeus spores is ≈11 nm thick, and has a periodicity of ≈8 nm (14). (b–d) Series of AFM height images tracking the initial changes of the rodlet layer after 13 min (b), 113 min (c), and 295 min (d) of exposure to germination solution. Small etch pits (indicated with arrows in b) evolve into fissures (indicated with an arrow in c) perpendicular to the rodlet direction. The fissures expand both in length and width. (e and f) Series of AFM images showing another germinating spore. The spore long axis, as well as major rodlet orientation, is left-right. Enhanced etching at stacking faults (running from left to center and indicated with an arrow in e), as well as increased etching at the perpendicular fissures, was visible after 135 min (e) and 240 min (f) of germination. Fissure width and length increased from 10–15 nm and 100–200 nm (135 min) to 15–30 nm and 125–250 nm (240 min), respectively. (g) Etching and/or fracture of the rodlet layer at a stacking fault revealed the underlying hexagonal layer of particles with a 10- to 13-nm lattice period. [Scale bars: 20 nm (a and g Inset) and 100 nm (b–g).]

Higher-Order Rodlet Structure.

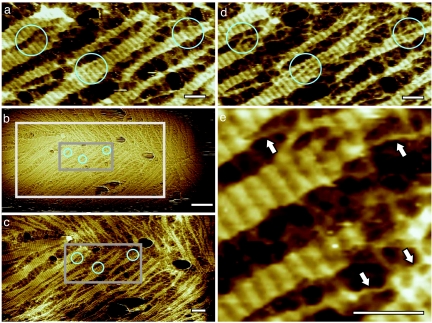

Disassembly of the higher-order rodlet structure began before the outgrowth stage of germination (Fig. 2). Disaggregation of the rodlet layer occurred perpendicular to the orientation of individual rodlets resulting in the formation of banded remnants (Fig. 2). Further structural disruption led to the formation of extended, 2- to 3-nm-wide fibrils (indicated with arrows in Fig. 2e), which were also oriented perpendicular to the rodlet direction.

Fig. 2.

Series of AFM height images showing the progress of rodlet disassembly. Time between images was 36 min (a to b), 3 min (b to c), and 6 min (c to d), for a total time between a and d of 45 min. In the circled regions, banded remnants of rodlet structure (a) disassemble into thinner fibrous structures (d). In b, the area imaged in c is indicated with a light gray box. In b and c, the area imaged in a and d is indicated with a dark gray box. In e, which is an enlarged part of d, arrows indicate the end point of rodlet disruption, i.e., fibrils with a diameter of 2–3 nm, oriented roughly perpendicular to the rodlets. [Scale bars: 50 nm (a and c–e) and 200 nm (b).]

The observed rodlet disassembly process seems not to be perturbed by the AFM scanning probe. Imaging using various scan angles did not influence either the appearance of the rodlet remnants and fibrils or their relative orientation. In addition, the rodlet disassembly processes producing fibrils were consistently observed both on spores that were imaged continuously from the onset of germination (Fig. 1), as well as on spores that were imaged only when rodlet degradation was already in progress. Finally, at all stages of the rodlet disassembly, prolonged scanning of a small area followed by a zoom-out to a large previously nonscanned area (Fig. 2 b and c) did not indicate any alterations in the morphology of the initially imaged area (such as increased etching).

Emergence of Vegetative Cells.

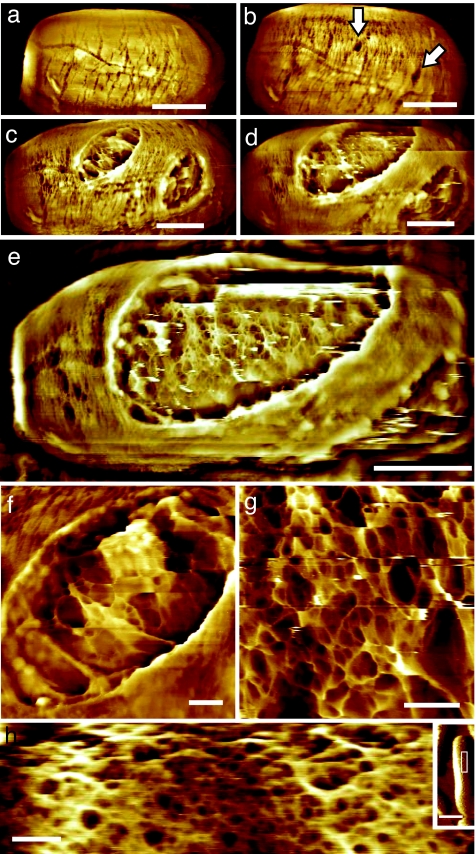

Etch pits were the initiation sites for early germination-induced spore coat fissure formation. During intermediate stages of germination, small spore coat apertures developed that were up to 70 nm in depth (Fig. 3b). During late stages of germination these apertures dilated (Fig. 3 c–e) allowing vegetative cell emergence (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Emergence of vegetative cells. (a–g) Series of AFM height images showing 60- to 70-nm-deep apertures in the rodlet layer (indicated with arrows in b) that gradually enlarged (c and d), and subsequently eroded the entire spore coat (e). Germ cells emerged from these apertures. (e) Before germ emergence from the spore coat, the peptidoglycan cell wall structure was evident. (f and g) At an early stage of emergence, the cell wall was still partly covered by spore remnants (f), whereas immediately before cell emergence, the cell wall was free of spore integument debris (g). The germ cell surface contained 1– to 6-nm fibers forming a fibrous network enclosing pores of 5–100 nm. Images in a–g were collected on the same spore as those shown in Fig. 1 e and f. Elapsed germination time (in hr:min) was as follows: (a) 3:40, (b) 5:45, (c) 7:05, (d) 7:30, (e) 7:45, (f) 7:15, (g) 7:50. (h) In separate experiments, cultured vegetative B. atrophaeus cells were adhered to gelatin surfaces and imaged in water. AFM height images show a slightly denser, similar fibrous network compared with the germ cell network structure (g), with 5– to 50-nm pores. (Inset) The imaged part (h) of the entire cell is indicated with a white rectangle. [Scale bars: 500 nm (a-e), 100 nm (f–h), and 1 μm (h Inset).]

In vitro AFM visualization of germling emergence allowed high resolution visualization of nascent vegetative cell surface structure (Fig. 3 e–g). Vegetative cell wall structure could be recognized through the apertures ≈30–60 min before germ cell emergence. The emerging germ cell surface was initially partially covered with residual patches of spore integument (Fig. 3f). During the release of vegetative cells from the spore integument, the entire cell surface consisted of a porous fibrous network (Fig. 3g).

To compare the cell wall structure of germling and mature vegetative cells, we carried out separate experiments in which cultured vegetative B. atrophaeus cells were adhered to a gelatin-coated surface (21), and imaged with AFM in water. As seen in Fig. 3h, the cell wall of mature vegetative cells contained a porous, fibrous structure similar to the structure observed on the surface of germling cells (Fig. 3g).

Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that in vitro AFM is a powerful tool for revealing the structural dynamics and architectural topography of the spore germination process. The ability to image single emergent vegetative cells at nanometer scale, under native conditions, also provides a powerful tool for investigating the biological structure of Gram-positive cell walls.

Electron microscopy (EM) techniques such as thin sectioning, freeze-fracturing, negative staining, and cryo-electron microscopy have been the primary tools used to study microbial surface structures (19, 22–24). AFM allows new approaches to high-resolution real-time dynamic studies of single microbial cells under native conditions (in air or in aqueous solution). Environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, chemistry, or gas phase) can be easily changed during the course of AFM experiments, allowing dynamic environmental and chemical probing of microbial surface reactions.

The AFM studies presented here elucidate the time-dependent structural dynamics of individual germinating spores and reveal previously unrecognized nano-structural alterations of the outer spore coat. Disassembly of the higher-order rodlet structure initiates at micro-etch pits, and proceeds by the expansion of the pits to form fissures perpendicular to the rodlet direction. What causes this breakdown of the rodlet layer? It is known that several lytic enzymes, which cause cortex hydrolysis, are located at the cortex-coat junction, inner membrane and in outer spore coat layers (2). We suggest by analogy that rodlet structure degradation is caused by specific hydrolytic enzyme(s), located within the spore integument and activated during the early stages of germination. The highly directional rodlet disassembly process suggests that coat degrading enzymes could be localized at the etch pits, and either recognize their structural features, or that the etch pits are predisposed to structural deformation during early stages of spore coat disassembly. The gradual elongation of the fissures suggests that once hydrolysis is initiated at an etch pit, processive hydrolysis propagates perpendicular to the rodlet direction and to neighboring rodlets.

The locations of the small etch pits may coincide with point defects in the rodlet structure. These point defects could be caused by misoriented rodlet monomers or by the incorporation of impurities into the crystalline structure. In both cases, point defects could facilitate access of degradative enzymes to their substrate in an otherwise tightly packed structure.

Recent proteomic and genetic studies suggest that the inner and outer spore coats of Bacillus subtilis, which is closely related to B. atrophaeus, are composed of >50 polypeptide species (25). However, it is unknown which of these proteins form the surface rodlet layer of the spore coat or how this outer spore coat layer is assembled. We have shown previously for Bacillus cereus spores (14) and here for B. atrophaeus spores (Fig. 1g) that the outer spore coat rodlet layer is underlain by a crystalline honeycomb structure.

The closest structural and functional orthologs to the Bacillus species rodlet structure (not its protein sequence) are found outside the Bacillus genus. Several classes of proteins, with divergent primary sequences, were found to form similar rodlet structures on the surfaces of cells of Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica as well as spores of Gram-positive streptomycetes and various fungi (26). These rodlets were shown to be structurally highly similar to amyloid fibrils (26). Amyloids possess a characteristic cross β-structure and have been associated with neural degenerative diseases (i.e., Alzheimer's and prion diseases) (27). Amyloid fibrils or rodlets form microbial surface layers (26), which play important roles in microbial attachment, dispersal and pathogenesis. Fungal hydrophobin rodlet layers cause hyphal fragments and spores to become water-repellent, which enables escape from the aqueous environment and stimulates aerial release, dispersal and attachment to hydrophobic host surfaces (26). The structural similarity of B. atrophaeus spore coat rodlets and the amyloid rodlets found on other bacterial and fungal spores suggests that Bacillus rodlets have an amyloid structure. AFM characterization of the nanoscale properties of individual amyloid fibrils has revealed that these self-assembled structures can have a strength and stiffness comparable with structural steel (28). The extreme physical, chemical and thermal resistance of Bacillus endospores suggests that evolutionary forces have captured the mechanical rigidity and resistance of these amyloid self-assembling biomaterials to structure the protective outer spore surface. AFM has played a pivotal role in revealing the powerful and pervasive forces of convergent evolution that have shaped prokaryotic and eukaryotic spore surface architecture (12–16, 28).

Structural studies of amyloids have identified an array of possible rodlet assemblies, each consisting of several (2 or 4) individual cross-β-sheet fibrils, which are often helically intertwined (26). The number of fibrils determines the diameter of the rodlet. Most amyloids resulting from protein-folding diseases, and some naturally occurring amyloids, form individual fibrils or disorganized rodlets networks. The in vitro self-assembly of fungal hydrophobin rodlet layers at hydrophobic/hydrophilic interfaces (29) may indicate that the amphiphilic nature of the hydrophobins is sufficient to (i) bring monomers and growing rodlets together in a confined two-dimensional (2D) layer, (ii) structurally orient their hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues in such a way that (iii) monomers attach to growing rodlets, and (iv) rodlets easily coalesce to form a closely packed layer.

In spore coats of B. atrophaeus, the higher-order rodlet structure is organized as one major domain of parallel rodlets covering the entire spore surface (16). Because of the close-packed, 2D crystalline nature of these rodlet domains, their self-assembly seems to be governed by principles similar to macromolecular crystallization, for which an extensive body of knowledge and theory exists. In particular, crystallization requires that there must be periodic bonds in every growth direction (30). Rodlet domain formation requires there must be periodic bonds in the rodlet direction (“parallel bonds”) as well in the direction perpendicular to it (“perpendicular bonds”). In the case of amyloid-like rodlets, the intra-rodlet, parallel bonds are known and consist primarily of hydrogen bonds associated with the cross-β-sheets that form the backbone of the rodlet fibrils. However, the nature of the perpendicular bonds, i.e., the inter-rodlet bonds that keep the rodlets tightly packed, is unknown. Based on the high degree of order in the domains, it is expected that in addition to the macroscopic hydrophilic/hydrophobic effect mentioned previously, there are specific, attractive rodlet-rodlet interactions that stabilize the structure in the perpendicular direction. Interestingly, for B. atrophaeus the ratio of length (parallel to rodlet direction) and width (perpendicular to rodlet direction) of the rodlet domains is on average ≈1 (16), indicating that during formation of these domains, growth velocity was similar in both directions, and hence parallel and perpendicular bonds were similar in strength.

Based on these rodlet features, one might expect that during germination individual rodlets would detach or erode, leaving a striated pattern parallel to the rodlet direction. Surprisingly, striations perpendicular to the rodlet direction were observed (Fig. 2), and 2– to 3-nm-wide fibrils perpendicular to the rodlet direction (Fig. 2e) were the culmination product of coat degradation. This result indicates that during germination, perpendicular rodlet bonds are stronger, or are more resistant to hydrolysis, than bonds parallel to the rodlet direction. Second, and most surprisingly, these perpendicular structures facilitate the formation, of 200–300 nm long fibers perpendicular to the rodlet direction.

It is unclear how microbial amyloid fibers form these perpendicular structures. One possibility is that during formation of the rodlet layer, both intra-rodlet parallel bonds and inter-rodlet perpendicular bonds form, similar in strength and leading to tightly packed rodlets domains held together by a checkerboard-like bonding pattern. During germination, the intra-rodlet parallel bonds are hydrolyzed, whereas the inter-rodlet perpendicular bonds remain intact over longer time periods. Spore coat hydrolytic enzymes could target a specific residue or structure (in this case, that of the cross-β-sheets) and leave other (here, perpendicular) residues or structures intact. Identification of the gene(s) encoding the rodlet structure and the enzymes responsible for rodlet degradation are important areas for future research.

The bacterial cell wall consists of long chains of peptidoglycan that are cross-linked via flexible peptide bridges (31, 32). Whereas the composition and chemical structure of the peptidoglycan layer vary among bacteria, its conserved function is to allow bacteria to withstand high internal osmotic pressure (31). The length of peptidoglycan strands varies from 3–10 disaccharide units in Staphylococcus aureus to ≈100 disaccharide units in B. subtilis, with each unit having a length and diameter of ≈1 nm (33). The fibrous network observed on the germ cell surface with 5– to 100-nm pores, (Fig. 3 e and g), and the fibrous network observed on mature vegetative cells with 5– to 50-nm pores (Fig. 3h) seem to represent the nascent peptidoglycan architecture of newly formed and mature cell wall, respectively, and is comprised of either individual or several intertwined peptidoglycan strands. The cell wall density of mature cells seems to be higher with, on average, smaller pores and more fibrous material, as compared with the germ cells. These results are consistent with murein growth models whereby new peptidoglycan is inserted as single strands and subsequently cross-linked with preexisting murein (34).

A similar fibrous network has been reported in AFM studies of Gram-positive S. aureus cell growth and division (35). The AFM-resolved pore structure of the nascent B. atrophaeus germ and vegetative cell surfaces, as well as S. aureus vegetative cell peptidoglycan is similar to the honeycomb structure of peptidoglycan oligomers (elementary pore size of 7 nm) determined by NMR (32). The pore size range is expected to increase with decreasing degrees of cross-linking (32). The B. atrophaeus cell wall pore structure (Fig. 3 e, g, and h) is consistent with the lower degree of cross-linking and broad glycan chain length distribution (25–100 disaccharide units) that is typical for B. subtilis (24, 33).

Spore germination provides an attractive experimental model system for investigating the genesis of the bacterial peptidoglycan structure. Dormant spore populations can be chemically cued to germinate with high synchrony (2), allowing the generation of homogenous populations of emergent vegetative cells suitable for structural analysis.

Proposed models for the bacterial cell wall structure posit that peptidoglycan strands are arranged either parallel (planar model) or orthogonal (scaffold model) to the cell membrane (31, 32). Existing experimental techniques are unable to confirm either the planar or the orthogonal model. The experiments described here do not contain sufficient high-resolution data, in particular of individual peptidoglycan strands, to deduce with certainty the tertiary three-dimensional peptidoglycan structure. The pore structures (Fig. 3 g and h) of the emergent germ and mature vegetative cell wall (an array of pores) suggest a parallel orientation of glycan strands with peptide stems positioned in stacked orthogonal planes (32). More detailed studies of germ cell surface architecture and morphogenesis will be required to confirm this peptidoglycan architecture and to investigate whether glycan biosynthesis precedes peptide cross-linking.

Materials and Methods

Spore and Vegetative Cell Preparation: Purification and Germination Conditions.

B. atrophaeus (ATCC 9372) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Spores were produced by using Schaeffer's sporulation medium and purified as described (36). Spore germination was induced by the addition of 100 mM l-alanine, 1.65 mM l-asparagine, 2.8 mM d-glucose, 2.8 mM d-fructose, 5 mM potassium chloride, and 25 mM Tris·HCl buffer, pH 8.0. The germination time course was characterized by phase contrast microscopy before performing AFM imaging. More than 95% of spores turned phase dark within 15 min, and cell outgrowth typically occurred within 3–7 h.

The same spore preparation was used to generate vegetative cells in liquid Difco nutrient broth (NB) media. After overnight incubation, the resulting suspension was streaked over NB agar plates. The next morning, single colonies could be isolated and were grown in tubes with NB. All incubation was done at 37°C.

AFM Imaging of Spores.

The outer surface of bacterial spores is highly hydrophobic. Thus, spores do not adhere well to hydrophilic substrates, such as mica and glass, when used in liquid AFM imaging. We found that bacterial spores adhered to polycoated vinyl plastic substrates with sufficient avidity for successful AFM imaging in fluid. These substrates were used exclusively for imaging of germinating bacterial spores. For AFM observations, a 1- to 2.5-μl droplet of a spore suspension (108 spores per ml) was deposited on the substrate and incubated for 10 min to allow spore adherence. The substrate was gently rinsed with double distilled water and transferred to the AFM fluid cell, which was typically filled with water first, for imaging a group of spores before germination. Subsequently, water was replaced with germinant solution to initiate spore germination. Germination experiments were conducted at 37°C. The time course of germination experiments varied between 2 and 15 h to allow for the completion of vegetative cell emergence.

Images were collected by using a Digital Instruments Multimode Nanoscope IV atomic force microscope (Veeco Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a tapping mode fluid cell, and exclusively operated in tapping mode. In our experiments, light tapping-mode imaging was exclusively used to minimize possible tip-induced effects on the spore coat structure. At these scanning conditions a minimal decrease in the applied force typically resulted in the detachment of the AFM tip from the scanning surface. Under stable conditions, the tapping amplitude was reoptimized at least once every hour to optimize resolution and contrast while keeping the tip-sample interaction forces low. The scan rate varied from ≈1 Hz for imaging of entire germinating spores to ≈2 Hz for high-resolution imaging of the structural dynamics of the rodlet spore coat layer.

A commercial Digital Instrument Multimode heater package, for use with standard scanners and AFM fluid cells, was used for sustained temperature control during the germination experiments. The temperature inside the AFM fluid cell was recorded with a thermocouple, and kept within 0.5°C of 37°C at all times. AFM probes consisting of silicon tips on silicon nitride cantilevers (force constants of ≈0.1 N/m, Veeco Instruments) were used at tapping frequencies of ≈9 kHz.

AFM Imaging of Vegetative Cells.

For AFM imaging of B. atrophaeus vegetative cells, the cell suspension was washed 2× by centrifuging 1 ml of culture for 2 min at 8,000 × g, and replacing the liquid with sterile ice cold double distilled water. After an additional centrifugation step, cells were resuspended in 100 μl of sterile water. Plastic cover slips cut into a 15-mm circle were dipped briefly in liquid porcine gelatin suspension (type A, 300 bloom, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and then left to dry vertically, resulting in a thin gelatin coverage. After drying, the gelatin-coated plastic was attached to a metal 15-mm AFM specimen disk (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). A droplet of B. atrophaeus cell suspension (3–5 μl) was deposited directly onto a gelatin-covered AFM disk and allowed to incubate for ≈10–20 min. The disk was transferred into the AFM fluid cell and imaged in water as described above for spore imaging.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract W-7405-Eng-48. This work is supported by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory through Laboratory Directed Research and Development Grant 04-ERD-002 and was funded in part by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. H.D.H. acknowledges that this research was performed while on appointment as a U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Fellow under the DHS Scholarship and Fellowship Program.

Abbreviation

- AFM

atomic force microscopy.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Gould GW. J Appl Bacteriol. 1977;42:297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1977.tb00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moir A. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setlow P. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce SM, Fitz-James PC. J Bacteriol. 1971;107:337–344. doi: 10.1128/jb.107.1.337-344.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driks A. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moir A, Corfe BM, Behravan J. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8432-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setlow P. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behravan J, Chirakkal H, Masson A, Moir A. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1987–1994. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1987-1994.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutima PM, Foegeding PM. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:47–52. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.1.47-52.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufrêne YF. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:451–460. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dufrêne YF, Boonaert CJP, Gerin PA, Asther M, Rouxhet PG. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5350–5354. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5350-5354.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao L, Schaefer D, Marten MR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:955–960. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.2.955-960.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Malkin AJ. Biophys J. 2005;88:603–608. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Malkin AJ. Langmuir. 2005;21:7892–7898. doi: 10.1021/la050412r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Pitesky ME, Malkin AJ. Langmuir. 2005;21:10710–10716. doi: 10.1021/la0517437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chada VGR, Sanstad EA, Wang R, Driks A. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6255–6261. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6255-6261.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaman MS, Goyal A, Dubey GP, Gupta PK, Chandra H, Das TK, Ganguli M, Singh Y. Microsc Res Tech. 2005;66:307–311. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santo LY, Doi RH. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:475–481. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.475-481.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Huang SS, Li YQ. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6936–6941. doi: 10.1021/ac061090e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doktycz MJ, Sullivan CJ, Hoyt PR, Pelletier DA, Wu S, Allison DP. Ultramicroscopy. 2003;97:209–216. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson AI, Fitz-James P. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:360–402. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.360-402.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beveridge TJ, Graham LL. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:684–705. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.684-705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matias VR, Beveridge TJ. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:240–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Hahn M, Grabowski P, McPherson DC, Otte MM, Wang R, Ferguson CC, Eichenberger P, Driks A. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:487–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gebbink MF, Claessen D, Bouma B, Dijkhuizen L, Wösten HA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:333–341. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobson CM. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JF, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, MacPhee CE, Welland ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15806–15811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wösten HA, de Vocht ML. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1469:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimbergen RF, Meekes H, Bennema P, Strom CS, Vogels LP. Acta Crystallogr A. 1998;54:491–500. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vollmer W, Höltje JV. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5978–5987. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.5978-5987.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meroueh SO, Bencze KZ, Hesek D, Lee M, Fisher JF, Stemmler TL, Mobashery S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4404–4409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward JB. Biochem J. 1973;133:395–398. doi: 10.1042/bj1330395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Höltje JV, Heidrich C. Biochimie. 2001;83:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touhami A, Jericho MH, Beveridge TJ. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3286–3295. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3286-3295.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longchamp P, Leighton T. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31:242–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]