Abstract

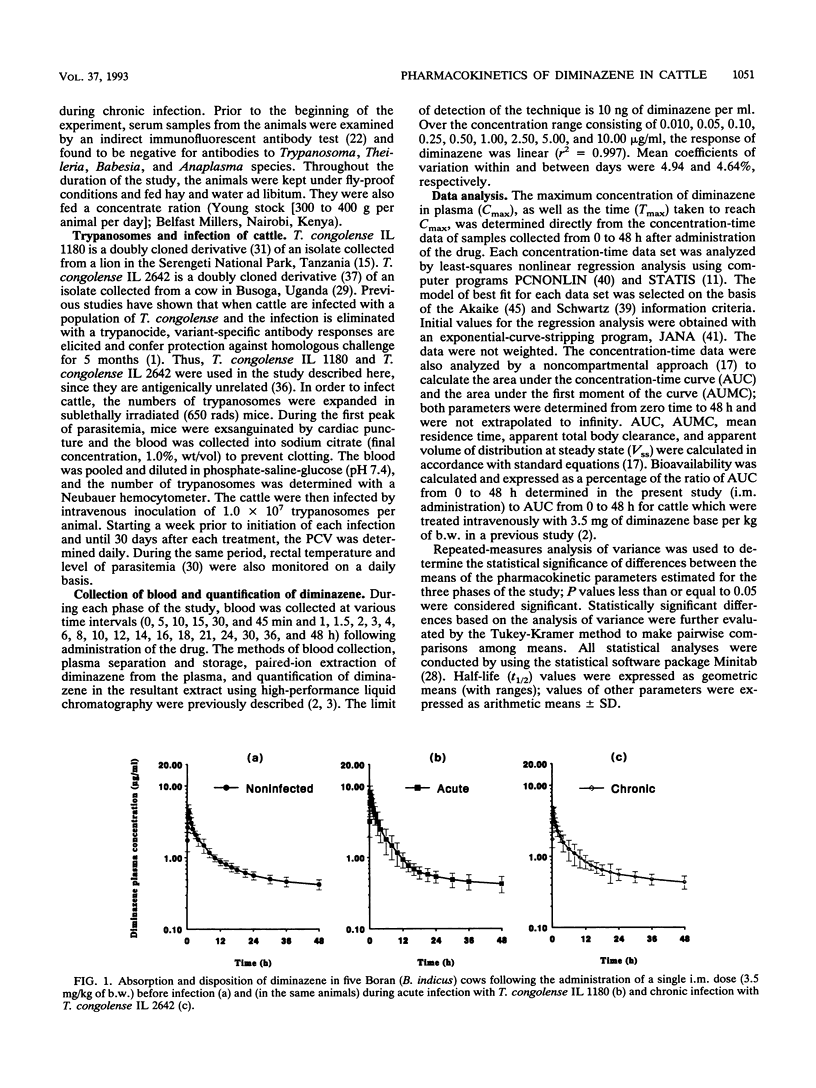

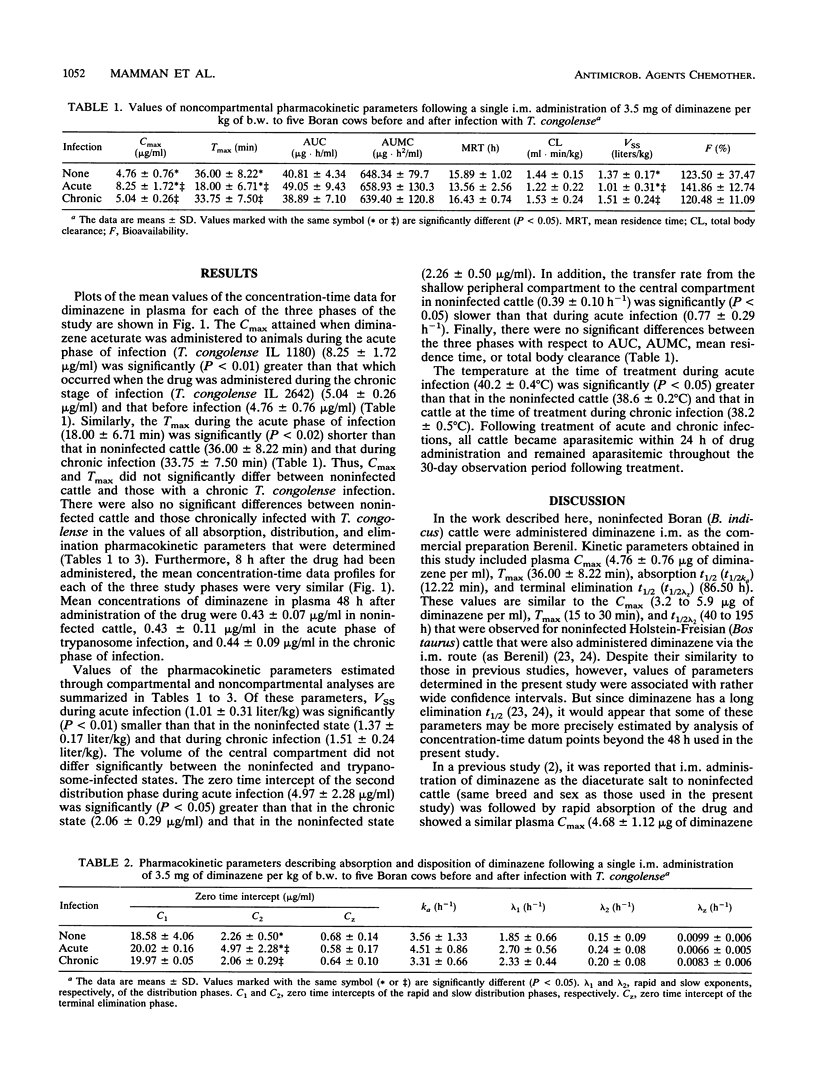

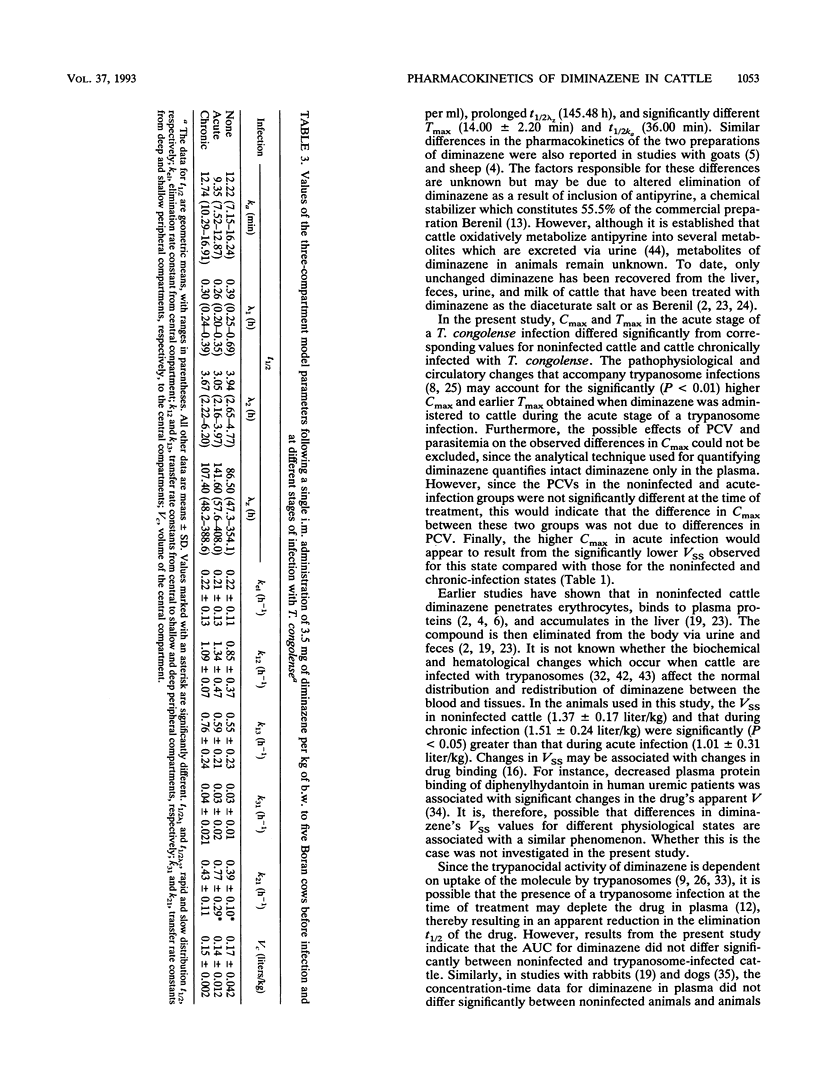

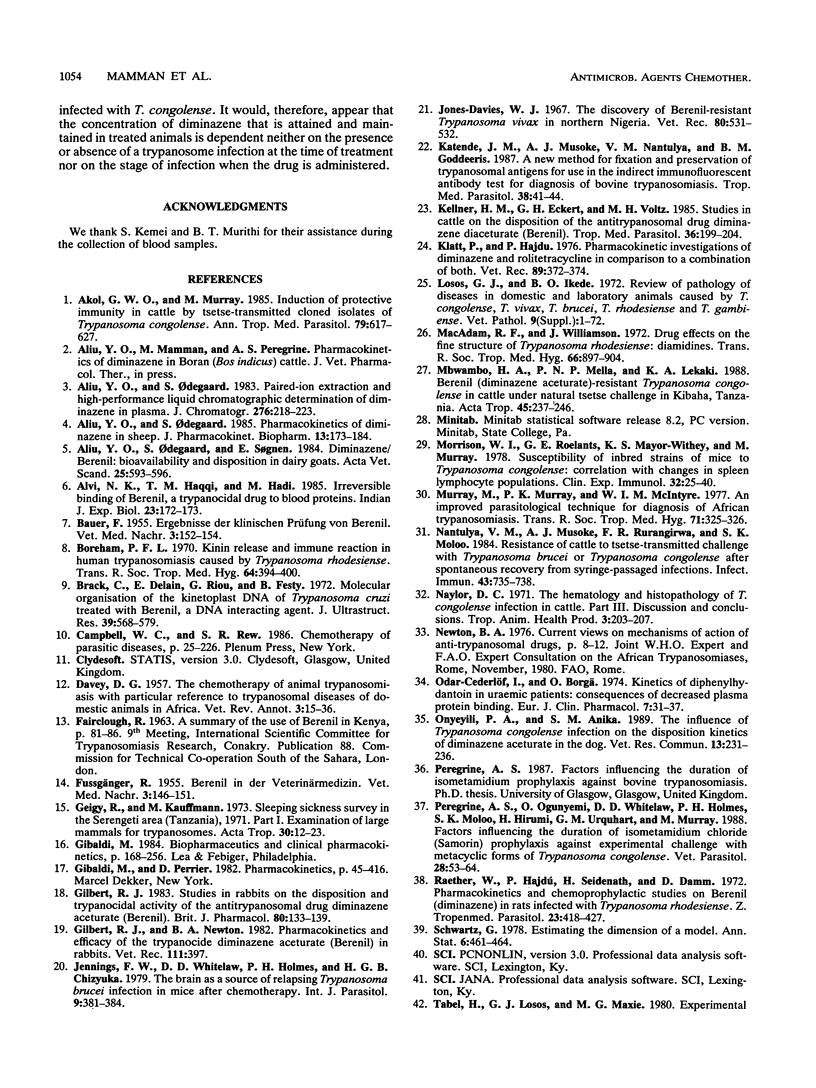

The pharmacokinetics of diminazene in five female Boran (Bos indicus) cattle before and then during acute and chronic phases of experimental infections with Trypanosoma congolense were investigated. A 7.0% (wt/vol) solution of diminazene aceturate (Berenil) was used in all three phases of the study and administered as a single intramuscular dose of 3.5 mg of diminazene base per kg of body weight. There were no significant differences between the values of pharmacokinetic parameters for the noninfected cattle and the values for cattle with a chronic T. congolense infection. However, the maximum concentration of the drug in plasma during the acute phase of infection (8.25 +/- 1.72 micrograms/ml) was significantly (P < 0.01) greater than that during chronic infection (5.04 +/- 0.26 micrograms/ml) and that in the noninfected state (4.76 +/- 0.76 micrograms/ml). Similarly, the time to maximum concentration of the drug in plasma when diminazene was administered during the acute phase of infection (18.00 +/- 6.71 min) was significantly (P < 0.02) shorter than that for noninfected cattle (36.00 +/- 8.22 min) and that during chronic infection (33.75 +/- 7.50 min). The volume of distribution at steady state during acute infection (1.01 +/- 0.31 liter/kg) was significantly (P < 0.01) smaller than that in the noninfected state (1.37 +/- 0.17 liter/kg) and that in chronic infection (1.51 +/- 0.24 liter/kg). Eight hours after the drug had been administered, the concentration-time data profiles for each of the three study phases were very similar. Mean concentrations of diminazene in plasma 48 h after administration of the drug were 0.43 +/- 0.07 microgram/ml in noninfected cattle, 0.43 +/- 0.11 microgram/ml during the acute phase of trypanosome infection, and 0.44 +/- 0.09 microgram/ml during the chronic phase of the infection. Results of the present study indicate that the area under the concentration-time curve for diminazene in trypanosome-infected cattle did not differ significantly for noninfected cattle. It, therefore, appears that the total amount of diminazene attained and maintained in the plasma of cattle is not significantly altered during infection with T. congolense.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akol G. W., Murray M. Induction of protective immunity in cattle by tsetse-transmitted cloned isolates of Trypanosoma congolense. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1985 Dec;79(6):617–627. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1985.11811969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliu Y. O., Odegaard S. Paired-ion extraction and high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of diminazene in plasma. J Chromatogr. 1983 Aug 12;276(1):218–223. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)85086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliu Y. O., Odegaard S. Pharmacokinetics of diminazene in sheep. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1985 Apr;13(2):173–184. doi: 10.1007/BF01059397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliu Y. O., Odegaard S., Søgnen E. Diminazene/Berenil: bioavailability and disposition in dairy goats. Acta Vet Scand. 1984;25(4):593–596. doi: 10.1186/BF03546926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvi N. K., Haqqi T. M., Hadi S. M. Irreversible binding of berenil, a trypanocidal drug to blood proteins. Indian J Exp Biol. 1985 Mar;23(3):172–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boreham P. F. Kinin release and the immune reaction in human trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1970;64(3):394–400. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(70)90175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack C., Delain E., Riou G., Festy B. Molecular organization of the kinetoplast DNA of Trypanosoma cruzi treated with berenil, a DNA interacting drug. J Ultrastruct Res. 1972 Jun;39(5):568–579. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(72)90122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigy R., Kauffmann M. Sleeping sickness survey in the Serengeti area (Tanzania) 1971. I. Examination of large mammals for trypanosomes. Acta Trop. 1973;30(1):12–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R. J., Newton B. A. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of the trypanocide diminazene aceturate (Berenil) in rabbits. Vet Rec. 1982 Oct 23;111(17):397–397. doi: 10.1136/vr.111.17.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R. J. Studies in rabbits on the disposition and trypanocidal activity of the anti-trypanosomal drug, diminazene aceturate (Berenil). Br J Pharmacol. 1983 Sep;80(1):133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb11058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings F. W., Whitelaw D. D., Holmes P. H., Chizyuka H. G., Urquhart G. M. The brain as a source of relapsing Trypanosoma brucei infection in mice after chemotherapy. Int J Parasitol. 1979 Aug;9(4):381–384. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(79)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katende J. M., Musoke A. J., Nantulya V. M., Goddeeris B. M. A new method for fixation and preservation of trypanosomal antigens for use in the indirect immunofluorescence antibody test for diagnosis of bovine trypanosomiasis. Trop Med Parasitol. 1987 Mar;38(1):41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner H. M., Eckert H. G., Volz M. H. Studies in cattle on the disposition of the anti-trypanosomal drug diminazene diaceturate (Berenil). Trop Med Parasitol. 1985 Dec;36(4):199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt P., Hajdu P. Pharmacokinetic investigations on diminazene and rolitetracycline in comparison to a combination of both. Vet Rec. 1976 Nov 6;99(19):372–374. doi: 10.1136/vr.99.19.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macadam R. F., Williamson J. Drug effects on the fine structure of Trypanosoma rhodesiense: diamidines. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1972;66(6):897–904. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(72)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison W. I., Roelants G. E., Mayor-Withey K. S., Murray M. Susceptibility of inbred strains of mice to Trypanosoma congolense: correlation with changes in spleen lymphocyte populations. Clin Exp Immunol. 1978 Apr;32(1):25–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M., Murray P. K., McIntyre W. I. An improved parasitological technique for the diagnosis of African trypanosomiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1977;71(4):325–326. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(77)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantulya V. M., Musoke A. J., Rurangirwa F. R., Moloo S. K. Resistance of cattle to tsetse-transmitted challenge with Trypanosoma brucei or Trypanosoma congolense after spontaneous recovery from syringe-passaged infections. Infect Immun. 1984 Feb;43(2):735–738. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.735-738.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor D. C. The haematology and histopathology of Trypanosoma congolense infection in cattle. 3. Discussion and conclusions. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1971;3(4):203–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02359581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odar-Cederlöf I., Borgå O. Kinetics of diphenylhydantoin in uraemic patients: consequences of decreased plasma protein binding. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1974;7(1):31–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00614387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyeyili P. A., Anika S. M. The influence of Trypanosoma congolense infection on the disposition kinetics of diminazene aceturate in the dog. Vet Res Commun. 1989;13(3):231–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00142049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peregrine A. S., Ogunyemi O., Whitelaw D. D., Holmes P. H., Moloo S. K., Hirumi H., Urquhart G. M., Murray M. Factors influencing the duration of isometamidium chloride (Samorin) prophylaxis against experimental challenge with metacyclic forms of Trypanosoma congolense. Vet Parasitol. 1988 Apr;28(1-2):53–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(88)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raether W., Hajdú P., Seidenath H., Damm D. Pharmakokinetische und chemoprophylaktische Untersuchungen mit Berenil an Wistar-Ratten (Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Z Tropenmed Parasitol. 1972 Dec;23(4):418–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabel H., Losos G. J., Maxie M. G. Experimental bovine trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma vivax and T. congolense). II. Serum levels of total protein, albumin, hemolytic complement, and complement component C3. Tropenmed Parasitol. 1980 Mar;31(1):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellde B., Lötzsch R., Deindl G., Sadun E., Williams J., Warui G. Trypanosoma congolense. I. Clinical observations of experimentally infected cattle. Exp Parasitol. 1974 Aug;36(1):6–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(74)90107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkamp R. F., Lohuis J. A., Nijmeijer S. M., Kolker H. J., Noordhoek J., van Miert A. S. Species- and sex-related differences in the plasma clearance and metabolite formation of antipyrine. A comparative study in four animal species: cattle, goat, rat and rabbit. Xenobiotica. 1991 Nov;21(11):1483–1492. doi: 10.3109/00498259109044398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka K., Nakagawa T., Uno T. Application of Akaike's information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978 Apr;6(2):165–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01117450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]