Abstract

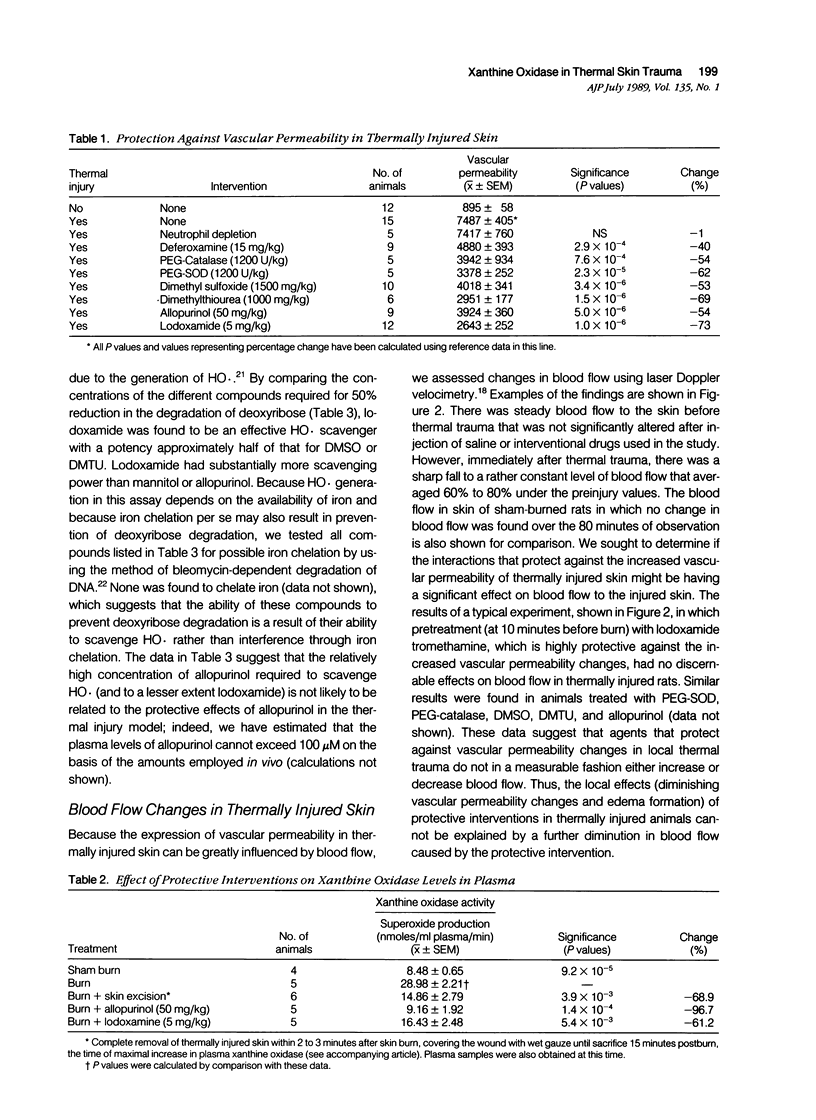

These studies were designed to assess pathophysiologic factors responsible for increased vascular permeability occurring in rat skin that has been thermally injured in vivo. Under the conditions employed, permeability changes and edema formation progressed over time, with peak changes occurring 60 minutes after thermal trauma. The plasma of thermally injured rats showed dramatic increases in levels of xanthine oxidase activity, with peak values appearing as early as 15 minutes after thermal trauma. Excision of the burned skin immediately after thermal injury significantly diminished the increase in plasma xanthine oxidase activity. The skin permeability changes were attenuated by treatment of animals with antioxidants (catalase, superoxide dismutase [SOD], dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO], dimethylthiourea [DMTU]) or an iron chelator (deferoxamine), supporting the role of oxygen radicals in the development of vascular injury as defined by greatly increased vascular permeability. Studies employing laser Doppler velocimetry in thermally injured skin revealed a pronounced and sustained decrease in blood flow after thermal trauma, a pattern not affected by protective interventions. The failure of neutrophil depletion to protect against the vascular permeability changes and the protective effects of the xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and lodoxamide tromethamine) suggest that xanthine oxidase is the most likely source of the oxygen radicals involved in edema formation. Lodoxamide was found to have some hydroxyl radical (HO.) scavenging ability (greater than that of allopurinol) but no iron chelating activity. Some of the protective effects of lodoxamide and allopurinol may be linked to their HO. scavenging ability. These data suggest that, in this model of thermal trauma, vascular injury defined by increased vascular permeability is, in part, related to the activation of xanthine oxidase and the generation of toxic oxygen metabolites that damage microvascular endothelial cells.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander F., Mathieson M., Teoh K. H., Huval W. V., Lelcuk S., Valeri C. R., Shepro D., Hechtman H. B. Arachidonic acid metabolites mediate early burn edema. J Trauma. 1984 Aug;24(8):709–712. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anggård E., Jonsson C. E. Efflux of prostaglandins in lymph from scalded tissue. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971 Apr;81(4):440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb04921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk J., Arturson G. Effect of cimetidine, hydrocortisone superoxide dismutase and catalase on the development of oedema after thermal injury. Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1983 Mar;9(4):249–256. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(83)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouhard B. H., Carvajal H. F. Effect of inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis on edema formation and albumin leakage during thermal trauma in the rat. Prostaglandins. 1979 Jun;17(6):939–946. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(79)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley G. B. Free radical-mediated reperfusion injury: a selective review. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1987 Jun;8:66–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal H. F., Brouhard B. H., Linares H. A. Effect of antihistamine-antiserotonin and ganglionic blocking agents upon increased capillary permeability following burn trauma. J Trauma. 1975 Nov;15(11):969–975. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demling R. H., Katz A., Lalonde C., Ryan P., Jin L. J. The immediate effect of burn wound excision on pulmonary function in sheep: the role of prostanoids, oxygen radicals, and chemoattractants. Surgery. 1987 Jan;101(1):44–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demling R. H., Lalonde C. Topical ibuprofen decreases early postburn edema. Surgery. 1987 Nov;102(5):857–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELROD P. D., McCLEERY R. S., BALL C. O. T. An experimental study of the effect of heparin on survival time following lethal burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951 Jan;92(1):35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl H. P., Till G. O., Trentz O., Ward P. A. Roles of histamine, complement and xanthine oxidase in thermal injury of skin. Am J Pathol. 1989 Jul;135(1):203–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Rowley D. A., Halliwell B. Superoxide-dependent formation of hydroxyl radicals in the presence of iron salts. Detection of 'free' iron in biological systems by using bleomycin-dependent degradation of DNA. Biochem J. 1981 Oct 1;199(1):263–265. doi: 10.1042/bj1990263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrecht G. S., Hilton J. G. The effects of catalase, indomethacin and FPL 55712 on vascular permeability in the hamster cheek pouch following scald injury. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1984 Jun;14(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(84)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatherill J. R., Till G. O., Bruner L. H., Ward P. A. Thermal injury, intravascular hemolysis, and toxic oxygen products. J Clin Invest. 1986 Sep;78(3):629–636. doi: 10.1172/JCI112620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway G. A., Jr, Watkins D. W. Laser Doppler measurement of cutaneous blood flow. J Invest Dermatol. 1977 Sep;69(3):306–309. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12507665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson O. P., Benediktsson G., Arturson G. Early post-burn oedema in leucocyte-free rats. Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1985 Oct;12(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(85)90178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarasch E. D., Bruder G., Heid H. W. Significance of xanthine oxidase in capillary endothelial cells. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem. 1969 Nov 25;244(22):6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey T. G., Höllwarth M. E., Granger D. N., Engerson T. D., Landler U., Jones H. P. Mechanisms of conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase in ischemic rat liver and kidney. Am J Physiol. 1988 May;254(5 Pt 1):G753–G760. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.5.G753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhouse P. C., Grootveld M., Halliwell B., Quinlan J. G., Gutteridge J. M. Allopurinol and oxypurinol are hydroxyl radical scavengers. FEBS Lett. 1987 Mar 9;213(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishigaki I., Hagihara M., Hiramatsu M., Izawa Y., Yagi K. Effect of thermal injury on lipid peroxide levels of rat. Biochem Med. 1980 Oct;24(2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(80)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham K. T., Guice K. S., Till G. O., Ward P. A. Activation of complement by hydroxyl radical in thermal injury. Surgery. 1988 Aug;104(2):272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCHA E SILVA M., ANTONIO A. Release of bradykinin and the mechanism of production of a "thermic edema (45 degrees C)" in the rat's paw. Med Exp Int J Exp Med. 1960;3:371–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodell T. C., Cheronis J. C., Repine J. E. Endothelial cell xanthine oxidase-derived toxic oxygen metabolites contribute to acute lung injury from neutrophil elastase. Chest. 1988 Mar;93(3 Suppl):146S–146S. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.3_supplement.146s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáez J. C., Ward P. H., Günther B., Vivaldi E. Superoxide radical involvement in the pathogenesis of burn shock. Circ Shock. 1984;12(4):229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till G. O., Beauchamp C., Menapace D., Tourtellotte W., Jr, Kunkel R., Johnson K. J., Ward P. A. Oxygen radical dependent lung damage following thermal injury of rat skin. J Trauma. 1983 Apr;23(4):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till G. O., Hatherill J. R., Tourtellotte W. W., Lutz M. J., Ward P. A. Lipid peroxidation and acute lung injury after thermal trauma to skin. Evidence of a role for hydroxyl radical. Am J Pathol. 1985 Jun;119(3):376–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till G. O., Johnson K. J., Kunkel R., Ward P. A. Intravascular activation of complement and acute lung injury. Dependency on neutrophils and toxic oxygen metabolites. J Clin Invest. 1982 May;69(5):1126–1135. doi: 10.1172/JCI110548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P. A., Till G. O., Hatherill J. R., Annesley T. M., Kunkel R. G. Systemic complement activation, lung injury, and products of lipid peroxidation. J Clin Invest. 1985 Aug;76(2):517–527. doi: 10.1172/JCI112001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P. A., Till G. O., Kunkel R., Beauchamp C. Evidence for role of hydroxyl radical in complement and neutrophil-dependent tissue injury. J Clin Invest. 1983 Sep;72(3):789–801. doi: 10.1172/JCI111050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G. J. Inhibition of oxidative enzymes by anti-allergy drugs. Agents Actions. 1981 Nov;11(5):503–509. doi: 10.1007/BF02004713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]