Abstract

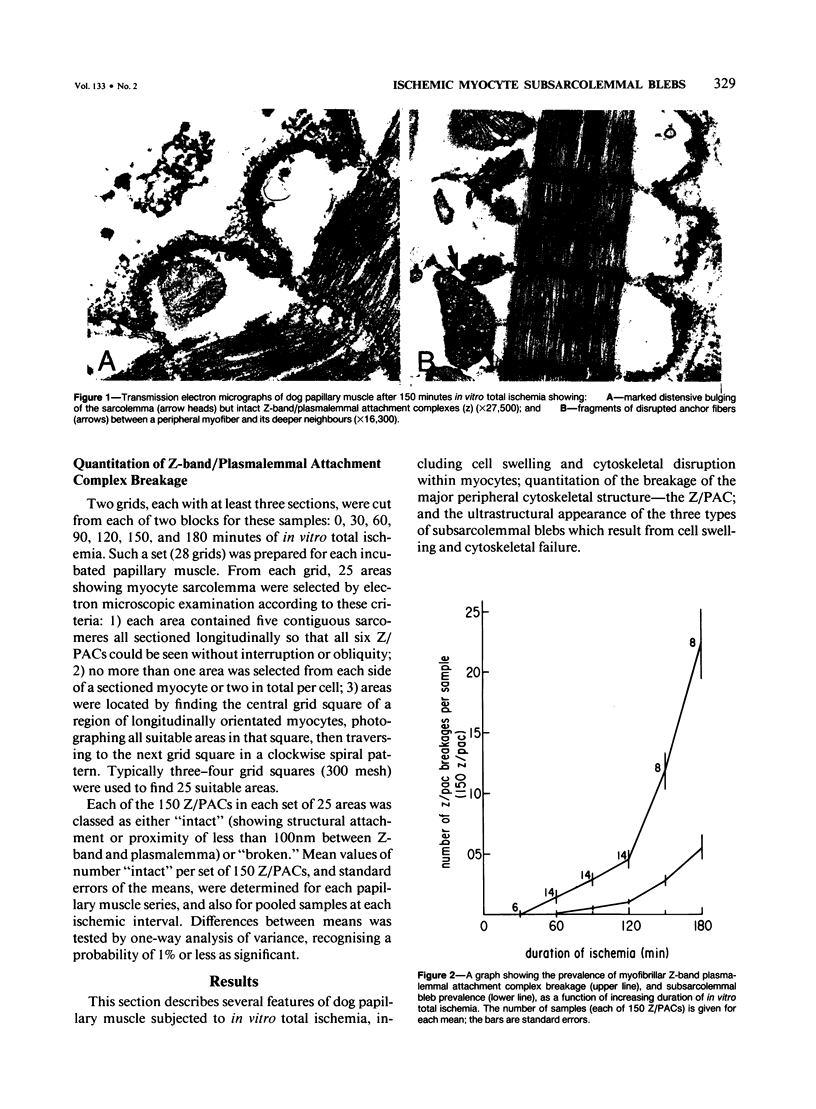

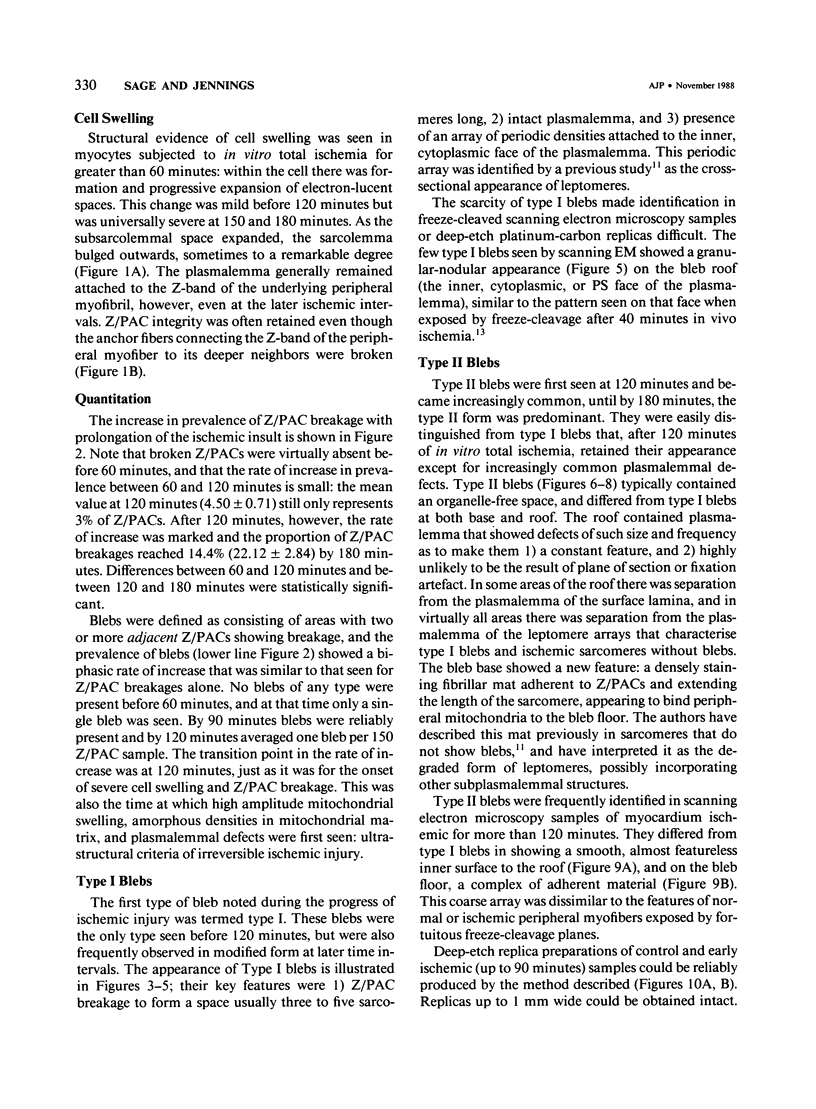

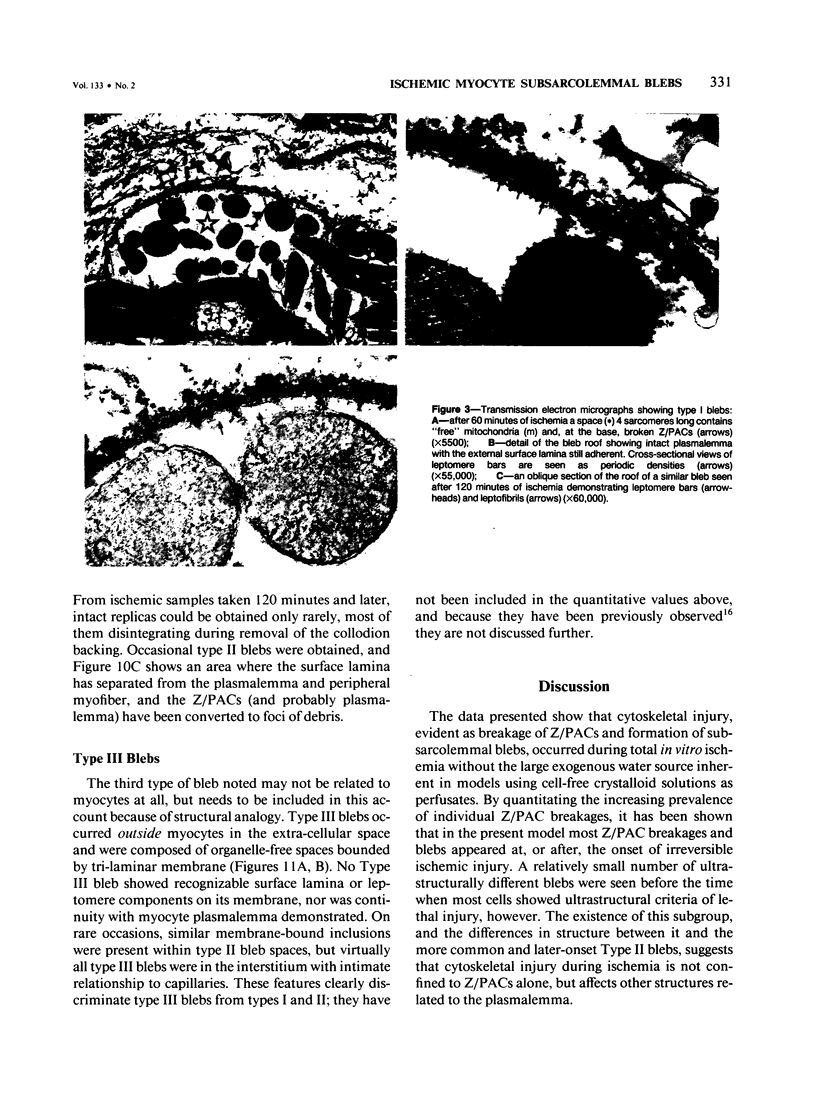

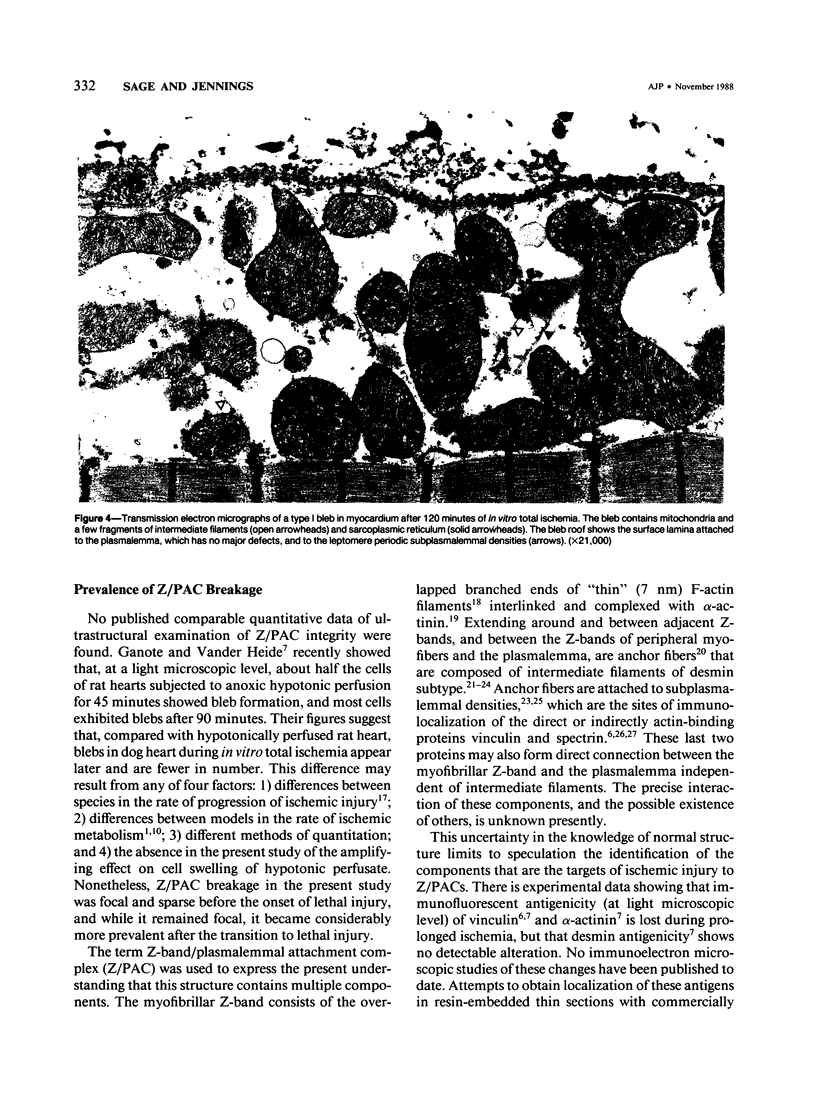

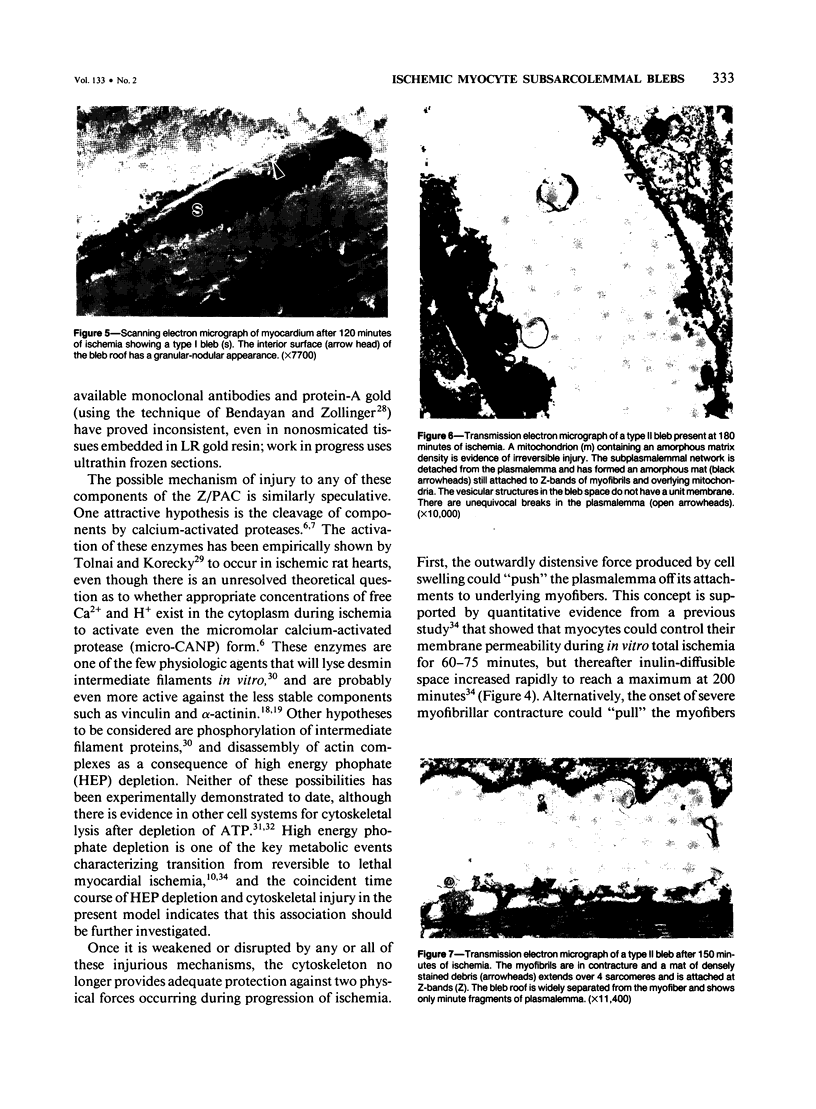

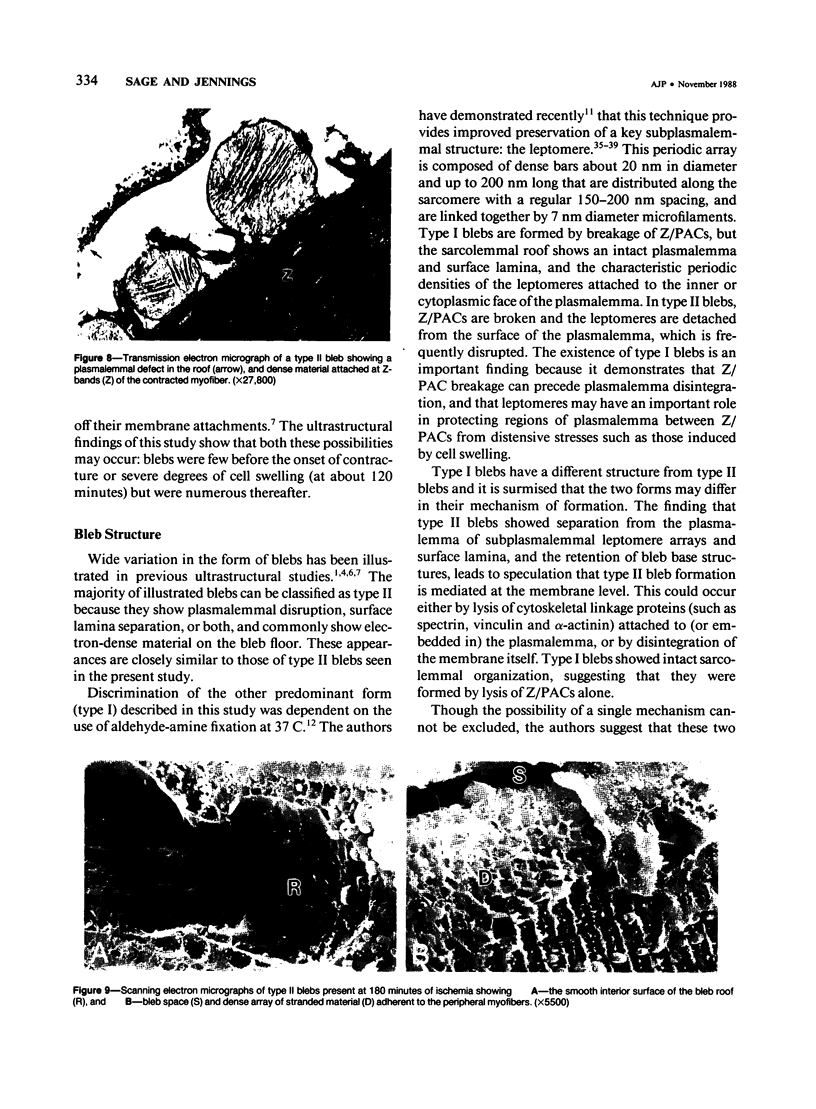

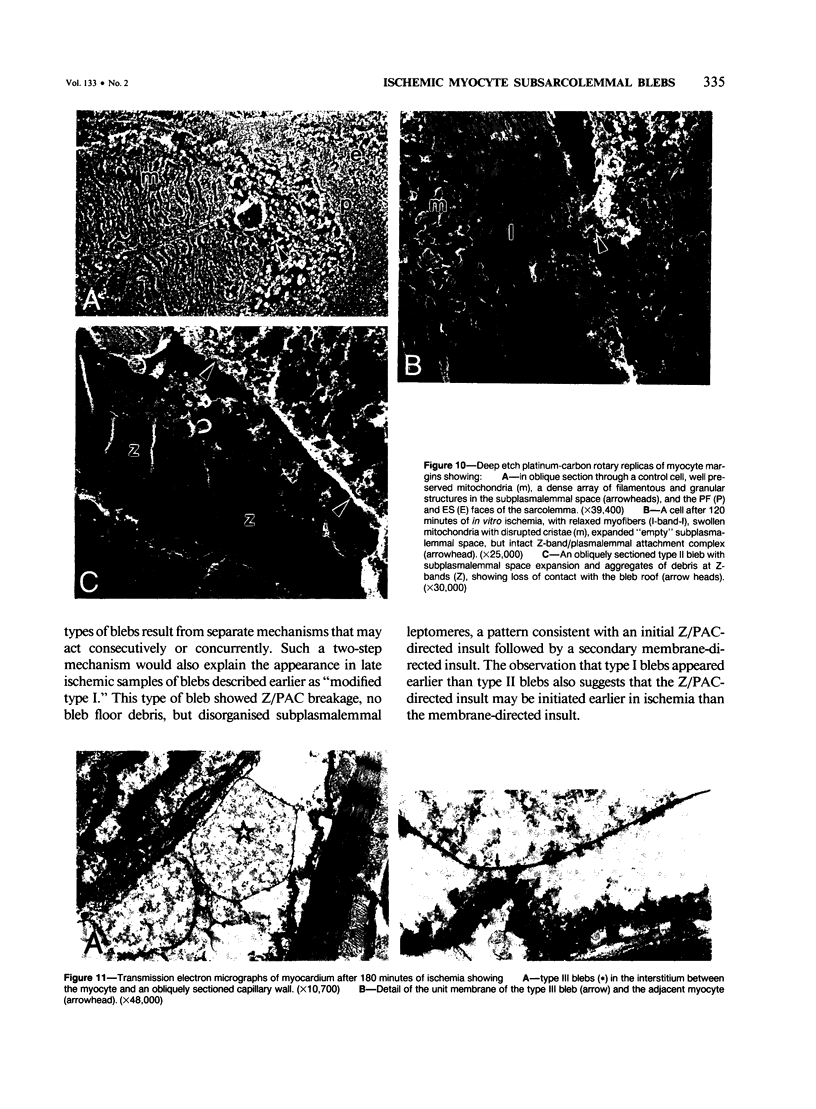

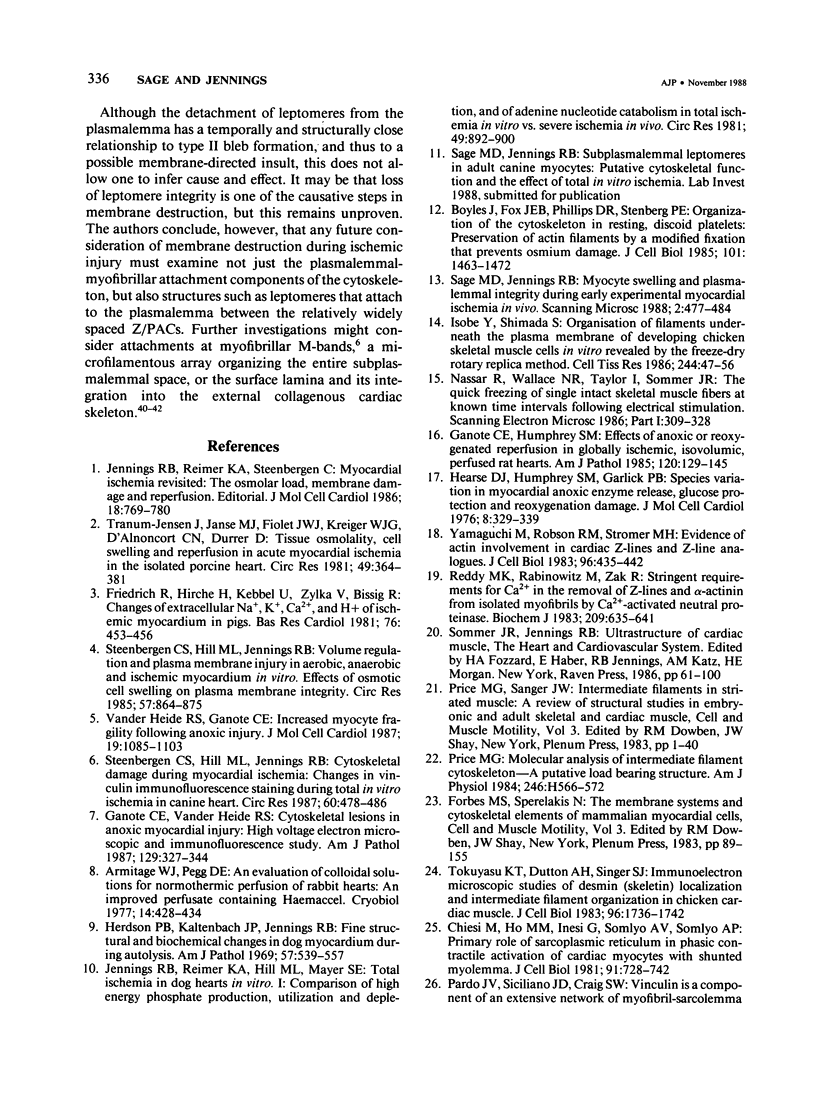

In previous studies a two-step hypothesis explaining the mechanism of lethal ischemic injury to cardiac myocytes has been advanced. It proposes that damage to the myocyte cytoskeleton precedes, and predisposes the cell to, mechanical injury induced by cell swelling or by ischemic contracture. This study quantitated the prevalence of breakage of the major cytoskeletal attachment between the plasmalemma and peripheral myofibers as a function of the duration (0-180 minutes) of in vitro total ischemia in dog heart papillary muscle. Breakages of Z-band, plasmalemmal attachment complexes were few before 120 minutes of ischemia, but thereafter became more prevalent; the transition between the initial rate of appearance of the breaks and the later fast rates coincided with the appearance of severe cell swelling, ischemic contracture, and ultrastructural criteria of irreversible ischemic injury. Z-band, plasmalemmal attachment complex breakage and cell swelling resulted in formation of subsarcolemmal blebs. Two major bleb types have been discerned on ultrastructural appearance using as the criteria the preservation of integrity of the plasma-lemma and subplasmalemmal leptomeres. The identification of two types of blebs suggests two independent mechanisms of injury, the first directed at Z-band attachments, and the second at the cytoskeletal structures of A- and I-band regions of the plasmalemma.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armitage W. J., Pegg D. E. An evaluation of colloidal solutions for normothermic perfusion of rabbit hearts: an improved perfusate containing haemaccel. Cryobiology. 1977 Aug;14(4):428–434. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendayan M., Zollinger M. Ultrastructural localization of antigenic sites on osmium-fixed tissues applying the protein A-gold technique. J Histochem Cytochem. 1983 Jan;31(1):101–109. doi: 10.1177/31.1.6187796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershadsky A. D., Gelfand V. I., Svitkina T. M., Tint I. S. Destruction of microfilament bundles in mouse embryo fibroblasts treated with inhibitors of energy metabolism. Exp Cell Res. 1980 Jun;127(2):421–429. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles J., Fox J. E., Phillips D. R., Stenberg P. E. Organization of the cytoskeleton in resting, discoid platelets: preservation of actin filaments by a modified fixation that prevents osmium damage. J Cell Biol. 1985 Oct;101(4):1463–1472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield J. B., Borg T. K. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest. 1979 Mar;40(3):364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesi M., Ho M. M., Inesi G., Somlyo A. V., Somlyo A. P. Primary role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in phasic contractile activation of cardiac myocytes with shunted myolemma. J Cell Biol. 1981 Dec;91(3 Pt 1):728–742. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes M. S., Sperelakis N. The membrane systems and cytoskeletal elements of mammalian myocardial cells. Cell Muscle Motil. 1983;3:89–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9296-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich R., Hirche H., Kebbel U., Zylka V., Bissig R. Changes of extracellular Na+, K+, Ca2+ and H+ of the ischemic myocardium in pigs. Basic Res Cardiol. 1981 Jul-Aug;76(4):453–456. doi: 10.1007/BF01908341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganote C. E., Humphrey S. M. Effects of anoxic or oxygenated reperfusion in globally ischemic, isovolumic, perfused rat hearts. Am J Pathol. 1985 Jul;120(1):129–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganote C. E., Vander Heide R. S. Cytoskeletal lesions in anoxic myocardial injury. A conventional and high-voltage electron-microscopic and immunofluorescence study. Am J Pathol. 1987 Nov;129(2):327–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearse D. J., Humphrey S. M., Garlick P. B. Species variation in myocardial anoxic enzyme release, glucose protection and reoxygenation damage. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1976 Apr;8(4):329–339. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(76)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdson P. B., Kaltenbach J. P., Jennings R. B. Fine structural and biochemical changes in dog myocardium during autolysis. Am J Pathol. 1969 Dec;57(3):539–557. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe Y., Shimada Y. Organization of filaments underneath the plasma membrane of developing chicken skeletal muscle cells in vitro revealed by the freeze-dry and rotary replica method. Cell Tissue Res. 1986;244(1):47–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00218380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Hawkins H. K., Lowe J. E., Hill M. L., Klotman S., Reimer K. A. Relation between high energy phosphate and lethal injury in myocardial ischemia in the dog. Am J Pathol. 1978 Jul;92(1):187–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Reimer K. A., Hill M. L., Mayer S. E. Total ischemia in dog hearts, in vitro. 1. Comparison of high energy phosphate production, utilization, and depletion, and of adenine nucleotide catabolism in total ischemia in vitro vs. severe ischemia in vivo. Circ Res. 1981 Oct;49(4):892–900. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.4.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Reimer K. A., Steenbergen C. Myocardial ischemia revisited. The osmolar load, membrane damage, and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1986 Aug;18(8):769–780. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(86)80952-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Steenbergen C., Jr, Kinney R. B., Hill M. L., Reimer K. A. Comparison of the effect of ischaemia and anoxia on the sarcolemma of the dog heart. Eur Heart J. 1983 Dec;4 (Suppl H):123–137. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/4.suppl_h.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. A., Sommer J. R. A strand of cardiac muscle. Its ultrastructure and the electrophysiological implications of its geometry. J Cell Biol. 1967 Apr;33(1):103–129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.33.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson U., Andersson-Cedergren E. Small leptomeric organelles in intrafusal muscle fibers of the frog as revealed by electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1968 Jun;23(5):417–426. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(68)80107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koteliansky V. E., Shirinsky V. P., Gneushev G. N., Chernousov M. A. The role of actin-binding proteins vinculin, filamin, and fibronectin in intracellular and intercellular linkages in cardiac muscle. Adv Myocardiol. 1985;5:215–221. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-1287-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menold M. M., Repasky E. A. Heterogeneity of spectrin distribution among avian muscle fiber types. Muscle Nerve. 1984 Jun;7(5):408–414. doi: 10.1002/mus.880070511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar R., Wallace N. R., Taylor I., Sommer J. R. The quick-freezing of single intact skeletal muscle fibers at known time intervals following electrical stimulation. Scan Electron Microsc. 1986;(Pt 1):309–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. G. Molecular analysis of intermediate filament cytoskeleton--a putative load-bearing structure. Am J Physiol. 1984 Apr;246(4 Pt 2):H566–H572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.4.H566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. G., Sanger J. W. Intermediate filaments in striated muscle. A review of structural studies in embryonic and adult skeletal and cardiac muscle. Cell Muscle Motil. 1983;3:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSKA H., EDWARDS G. A. A new cytoplasmic pattern in striated muscle fibers and its possible relation to growth. Growth. 1957 Jun;21(2):73–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M. K., Rabinowitz M., Zak R. Stringent requirement for Ca2+ in the removal of Z-lines and alpha-actinin from isolated myofibrils by Ca2+-activated neutral proteinase. Biochem J. 1983 Mar 1;209(3):635–641. doi: 10.1042/bj2090635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T. F., Cohen-Gould L., Factor S. M. Skeletal framework of mammalian heart muscle. Arrangement of inter- and pericellular connective tissue structures. Lab Invest. 1983 Oct;49(4):482–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage M. D., Jennings R. B. Myocyte swelling and plasmalemmal integrity during early experimental myocardial ischemia in vivo. Scanning Microsc. 1988 Mar;2(1):477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen C., Hill M. L., Jennings R. B. Cytoskeletal damage during myocardial ischemia: changes in vinculin immunofluorescence staining during total in vitro ischemia in canine heart. Circ Res. 1987 Apr;60(4):478–486. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen C., Hill M. L., Jennings R. B. Volume regulation and plasma membrane injury in aerobic, anaerobic, and ischemic myocardium in vitro. Effects of osmotic cell swelling on plasma membrane integrity. Circ Res. 1985 Dec;57(6):864–875. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.6.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOENES W., RUSKA H. [On "leptomere myofibrils" in the myocardial cells]. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1960;51:560–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyasu K. T., Dutton A. H., Singer S. J. Immunoelectron microscopic studies of desmin (skeletin) localization and intermediate filament organization in chicken cardiac muscle. J Cell Biol. 1983 Jun;96(6):1736–1742. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolnai S., Korecky B. Calcium-dependent proteolysis and its inhibition in the ischemic rat myocardium. Can J Cardiol. 1986 Jan-Feb;2(1):42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranum-Jensen J., Janse M. J., Fiolet W. T., Krieger W. J., D'Alnoncourt C. N., Durrer D. Tissue osmolality, cell swelling, and reperfusion in acute regional myocardial ischemia in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res. 1981 Aug;49(2):364–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heide R. S., Ganote C. E. Increased myocyte fragility following anoxic injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987 Nov;19(11):1085–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virágh S., Challice C. E. Variations in filamentous and fibrillar organization, and associated sarcolemmal structures, in cells of the normal mammalian heart. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969 Sep;28(5):321–334. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)80025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M., Robson R. M., Stromer M. H. Evidence for actin involvement in cardiac Z-lines and Z-line analogues. J Cell Biol. 1983 Feb;96(2):435–442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]